Matthew Carr's Blog, page 13

August 31, 2023

Not in the Same Boat

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

no one crawls under fences

no one wants to be beaten

pitied

Warsan Shire

In a world that overflows with content, it can be difficult to decide what to watch and read. But millions of people in the UK would benefit from watching Sally El Hosaini’s stirring film The Swimmers, which you can see on Netflix. The film tells the story of the teenage Mardini sisters, who were on their way to becoming Olympic swimmers in Syria, before the civil war broke their country to pieces.

As a result they were forced to become refugees in 2015, and made their way to Germany, where they were able to settle as a result of Angela Merkel’s open-door policy. One of the sisters went on to swim for a specially convened Refugee Team at the Rio Olympics in 2016.

That’s the bare bones of ‘the plot.’ But there is so much more to The Swimmers than plot. Films about refugees don’t have to be uplifting. Those of us who have never been stateless and never had to live outside our national borders without a passport, and whose government is actively seeking to make life worse for those who do, cannot expect a warm glowing feeling as the credits roll on the rare occasions when refugees become the subject of semi-fictionalised dramas.

In depicting the journey of the Mardini sisters, The Swimmers shows with painful clarity the journeys that thousands of refugees made in 2015, the year of ‘Europe’s migrant crisis’. It shows the route from Syria to Turkey, across the sea to Lesvos and then through the Balkans and into Orban’s Hungary and then Germany.

It shows the rip-off merchants and the predators, the would-be rapists, the wire fences with police, guards and dogs all deployed specifically to snag refugees at the border. There is a long and particularly terrifying sequence in which an overloaded dinghy nearly sinks between Turkey and Lesvos - a voyage that will be taking place somewhere in the world even as I write these lines.

The film also captures the hope, resilience, courage and determination of the men and women who made these journeys - and the little acts of humanity performed by some of the people who help them. It shows their dreams, aspirations, and friendships, their ties to each other and their families, and their personal conflicts.

It’s a funny, moving and even joyful film that deepens our understanding of humanity and what it means to be a stateless human being in our century of proliferating walls and fences.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It chimed very powerfully with my own memories of the migrants and refugees I met during my journeys to Europe’s borders between 2010 and 2012, to research Fortress Europe. Too many Europeans are accustomed to seeing refugees as a faceless mass of desperation and human misery, worthy of pity rather than respect - often without being aware of how easily pity can dehumanise the people it is extended to.

I don’t want to imply that refugees are generically better or worse than any other category of humanity. But I can say that I met many men and women who I regarded as genuinely heroic - if sometimes reckless and naive - in their determination to risk everything to help their families, and their refusal to accept the ‘paper walls’ or the formidable barriers placed in their path by some of the most powerful governments on earth.

Needless to say, the refugees I met, and the refugees who appear in The Swimmers, are not the refugees depicted by the UK government and the rightwing media, or the endless fascistic ‘Stop the Boat’ trolls who pollute Twitter day after day with their sinister depictions of ‘young men of military age’, ‘parasites’, ‘rapists’, and ‘benefit scroungers’ arriving in the UK.

In a powerful piece in the Guardian last week, Aditya Chakraborty reported on the protests taking place at the Stradey Park Hotel in LLanelli, where asylum seekers were expected to be housed while waiting for their applications to be processed. So far this has not happened, but the likes of Katie Hopkins, Richard Tice, Anne-Marie Waters and GB News have all gone to Wales to pour douse more petrol on the bonfire of fear and hatred that one local anti-racist activist called ‘far-right radicalisation in real time.’

In effect, Stradey Park has become one more flashpoint in the ‘Stop the Boats’ nightmare that we can’t wake up from, in part because the UK government doesn’t want us to wake up from it.

A Manufactured NightmareIn the same week that I watched The Swimmers, it was announced that the UK asylum backlog has reached 175,457 - 44 percent higher than it was last year. This means that 175,457 people are living or partly-living in the UK at the state’s expense - or rather at the expense of the ‘the taxpayer’’ as our saloon bar racists like to put it - with no permission to work, study, or do anything that might enable them to live the semblance of the normal lives that the rest of us live even in these abnormal times.

Instead they are housed in hotels, detention centres, and barges - where they present a constantly visible ‘problem’ that can be picked on week after week. Either they are living in the lap of luxury, according to the ‘we must look after our own people’ lobby, and all the racists who leap onto that bandwagon in an attempt to give themselves a semblance of moral gravitas. Or as Lee Anderson helpfully reminded us, they are ungrateful for not accepting the worst conditions we can give them.

The government knows this is happening, and does nothing to challenge it. Not one tiny dicky bird, or even the ghost of a whisper to suggest that it is not the fault of asylum seekers if they end up in hotels.

Instead it presents deportations to Rwanda as some kind of magical formula that will ‘Stop the Boats’, even though it has yet to produce even a shred of evidence or a convincing argument that the removal of a few hundred migrants to Rwanda would have any impact whatsoever on reducing Channel crossings.

It simply asks the public to believe in Rwanda, like a cargo cult in reverse, in which people will miraculously vanish from the Channel as soon as the first planeload takes off to fulfil Suella Braverman’s ‘dream.’ And then when these flights don’t take off, because the government hasn’t even done basic legal research into what is possible, it whines about ‘activist lawyers’, politicized charities, the ECHR and anyone else it can blame for sabotaging its ability to implement the ‘will of the British people.’

In a way its win-win, even if the ‘illegals’ always lose. But it’s also awful, pernicious clownery.

The previous week, the Home Office took 39 asylum seekers off the Bibby Stockholm barge, only a few days after putting them on it, because Legionnaire’s disease was discovered in the water supply. It was then revealed that the Home Office hadn’t carried out the safety checks it was asked to do, and said it had done.

Now Suella Braverman is proposing to return the asylum seekers to a barge that the Fire Brigades Union has called a ‘floating death trap.’ Asked what she thought of these warnings, Braverman accused the Labour-affiliated FBU pf carrying out a ‘political attack’.

This is a level of debate that makes the average primary school playground conversation look like high diplomacy. The most charitable explanation for these failings would be to assume that those responsible are merely epically incompetent. But the longer the crisis goes on, the more difficult it is not to conclude that the government is deliberately allowing it to continue, in the hope of extracting political benefits from it.

If that means dehumanizing asylum seekers, and setting them up to a resentful public as objects of fear, hatred, and resentment, then so be it.

Braverman - one of the most atrociously dishonest and inept politicians this country has ever produced - has openly pandered to such dehumanization by calling asylum seekers ‘criminals’ and describing Channel crossings as an ‘invasion’, which is exactly what every common or garden racist says it is.

This isn’t just incompetence. It’s so much worse than that. For the first time in British history, there is now an open - as opposed to covert or surreptitious - alignment between the UK government and the far-right on the issue of migration and asylum.

All this is being done entirely to protect the political interests of the Tory Party. The government clearly hopes that it can use Channel boat crossings to present Labour as ‘soft on migration’ and scrape some more votes from the bottom of the barrel that might enable it to keep its grubby fingers on the nation’s throat. And the Head Boy and his team are desperate to distract from the ‘cost of living crisis’ by turning popular anger and resentment towards anyone but them.

It’s all so brazen and transparent, as well as unbelievably cynical and downright dangerous. Because once these lines are crossed, anything becomes possible. And if you can convince the public to see performative cruelty as an antidote to the problem you helped create, then you can also crank up the cruelty.

The UK isn’t entirely unique in this regard. Most European countries, and the EU have been playing the same game for many years now. Long gone are the years when Vietnamese ‘boat people’ were grudgingly accepted as worthy refugees because they came from a communist country.

We are far from that now, in a world where national borders have progressively hardened in response to international problems, in an attempt to halt or at slow down the movements of people seeking to escape their own countries. This is a world where migrants and asylum seekers can be shot down by Saudi or Spanish border guards, abandoned to drown in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, ‘pushed back’ across the Evros river or the Río Grande, or ‘offshored’ to Naura Island.

Until migrants began crossing the Channel post-Brexit, the UK hadn’t seen such movements actually unfolding on its borders, because many of the refugees and migrants who wanted to enter the country were trapped long before they got here, by the EU’s ‘external’ borders and de-territorialised border controls that reached even further outwards.

The present ‘crisis’ is unfolding at a particularly dangerous moment in the country’s history, when all kinds of political possibilities are emerging that didn’t seem possible before. There is a lot of anger and resentment that, like our overflowing sewage system, seeks an outlet, and an empowered and virulent ethnonationalism has taken control of the Tory Party which feeds politically on foreign threats.

The government knows all this, but can’t or won’t do anything about it. Instead it has treated the crisis as a problem but also as an opportunity, and a populist metric.

It’s no use Braverman, Jenrick, Sunak, Tugendhat & co churning out the tired ‘evil criminal gangs’ rhetoric to disguise the fundamental cruelty at the heart of the government’s refugee policy. Because it is so obviously targeting asylum-seekers, not criminal gangs. And in doing so, it is giving the public a license to fear and hate the former.

You can’t sink much lower on the scale of political depravity than that. But there is another side to this nightmare. And other paths that we might take. The Swimmer shows us what they are. And so does the open letter which the 39 asylum seekers sent to the Home Office last week:

We are writing to explain that we were running from persecution, imprisonment and harsh tortures, with hearts full of fears and hope from the countries we were born in, to find safety and freedom in your country and our new refuge.

It is hard to Imagine that we, who used to live under harsh tortures and danger of persecution in our country, have been forced to leave our homes, our jobs and our families, and some of us haven't seen our families for months.

This abandonment and separation from our family has been bitter and painful, and has been accompanied day by day with anxiety and nervous stresses and only a combination of hope and fear remains within us.

We shouldn’t need to be told this. We should be able to hear these voices and take them seriously. We should not have the temerity to even suggest that such people have risked so much simply in order to live on a barge on £36 a week. We should have enough imagination and enough humanity to be able to imagine the humanity of the people who come here seeking refuge and a chance to rebuild their lives.

We should be able to give them a chance to do this and make it possible for them to play a positive role in our society. We should listen to the 39 asylum seekers who told us ‘respectfully and hopefully’:

Now, we seek refuge in you and hope to walk alongside you on this path with your support and unity. We believe that with our joint effort, we can overcome these unfavourable conditions and achieve the peaceful and secure life that we aspire to.

We need to accept that invitation. We need an asylum system that works effectively. We need safe routes. We need cooperation with other countries that is not centred on hardening borders, building ‘deterrents’, trapping people and exposing them to hardship and death.

To achieve any of this, we need to recognize that all of us are in the countries we are in out of luck and the quirks of fate and the vagaries of politics, and not because of our individual brilliance.

Our good fortune doesn’t give us the right to dismiss stateless people as ‘illegals’ and invaders if they come to our shores looking for help or simply a chance to stand on their own feet.

We shouldn’t allow the difficult times that many of us are going through to turn us against people who have also been in difficulty, in many cases much worse than ours.

So watch The Swimmer, because in this world of trouble, it tells a story that we haven’t been hearing, that deserves to be heard, and which too many of those who claim to want to ‘put our own people first’ don’t want us to hear.

And if we start listening to them, we might just be able to imagine a different kind of future to the dystopia we are currently constructing.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

August 24, 2023

Suffer the Little Children

If there’s one thing the new conservative/hard right populists care about, it’s children. We know this, because they never stop trying to warn us that children are in danger from drag queens, woke teachers, abortionists, Muslim ‘grooming gangs’, migrants, the Clintons, and paedophiles. Donald Trump, Kari Lake, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Ron DeSantis, Steve Bannon, ‘Tommy Robinson’, Katie Hopkins, Suella Braverman - they are only trying to protect children from the forces of evil that the media/elite/left/woke establishment dares not confront and may even be colluding with.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

According to the QAnon cultists, Trump became president specifically to save children from deep state paedophile rings, and would have saved them, had he not been cheated out of his rightful electoral victory.

That’s the kind of guy he is. And the kind of people his supporters are. The kind of people who, in the summer of 2020, used the #Savethe Children and #stophumantrafficking hashtags to promote an entirely baseless conspiracy theory in which a satanic/child-murdering network was supposedly trafficking 300,000 children every year.

And that’s only the start. Because the QAnonists would also have you believe that liberal Hollywood stars and Democrat politicians are torturing children in order to ‘harvest’ the adrenaline-related adrenochrome from their brains that would keep them forever young. Adrenochrome is the psychedelic chemical that Hunter Thompson gets high on in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which he insists can only be extracted from ‘a living human body.’

Thompson was just having fun. The QAnon circus barkers are absolutely serious. Hilary Clinton. Bill Gates. Tom Hanks. Oprah. Celine Dion, George Soros (of course) - they’re all businly sucking eternal youth from children’s brains. Even the Wayfair furniture company was involved in the trafficking business, apparently because it once sold a pillow with the same name as a missing child.

Bear that in mind next time you send off for a bedside table.

It’s easy - and necessary - to mock such howling drivel. But we shouldn’t laugh too much, because nonsense like this does have a purpose. History has shown again and again that if you want to make people hate and fear, one of the best ways you can do it is by accusing your enemies of harming or wanting to harm your children.

This is why fantasies of the Jewish ritual murder of children so often feature in outbreaks of medieval antisemitism, and in the twentieth century in the pages of the Nazi newspaper Die Sturmer:

![Front page of the most popular issue ever of the Nazi publication, Der Stürmer, with a reprint of a medieval depiction of a purported ... [LCID: 37858]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1692975839i/34646667._SY540_.jpg)

The QAnoners have no problem reaching into these sordid anti-semitic tropes, because these are the toxic waters they swim in, and would have us all swimming in. The people who propagate and subscribe to such ‘theories’ inhabit a political space in which simply having ‘political opponents’ who you disagree with or don’t like is no longer enough - you have to hate them and everything they stand for. They need their target audience to remain in a permanent state of fear, horror, and outrage at the absolutely depraved evil being perpetrated by absolutely depraved conspiracies against children.

If this means convincing them that Hilary Clinton and Bill Gates are drinking the blood of children at sex orgies, then so be it. And if you can make people believe that a furniture company names its products after kidnapped children, then you can convince them of pretty much anything. It’s not for nothing that QAnon supporters segue so easily into ‘scamdemic’/anti-vax/anti-mask/5G-n-your-veins’ hysteria, and depict the pandemic and everything related to it as another Diabolical Evil Conspiracy Product.

And whatever the scam, you can guarantee that children will be part of it. Why were children forced to wear masks? To make it impossible to identify their faces so that the abductors and human traffickers can get hold of them more easily. Why did Bill and Melinda Gates vaccinate children against polio in Sierra Leone? To give them polio.

And so on and so on. And as mad and hateful as these stories are, they are also useful to people who don’t necessarily believe them

One of those people is Donald Trump, who last month held a special screening of the ‘QAnon film’ Sound of Freedom at his golf club in New Jersey, with the likes of Kari Lake and Steve Bannon in the audience, in addition to the film’s lead actor Jim Caviesel. The film is ostensibly a thriller, about a US government agent who rescues Honduran kids from Columbian sex traffickers, who just happen to be members of the FARC.

Though its director has denied any connection between his movie and the QAnon movement, Caviesel has embraced ‘adrenochrome’ stories and QAnon has embraced the fim. Sound of Freedom has been widely-criticized by anti-trafficking organizations for portraying child sex trafficking as primarily a cross-border/inter-state activity.

Not that Trump and his cronies care. One of Caviesel’s line ‘God’s children are not for sale’ has become as well-known as the film itself. ‘Wow.Wow. Wow. GO SEE #SoundofFreedom’, tweeted a clearly-distressed Ted Cruz, while Senator Tim Scott praised a ‘powerful film that reveals the horrifying reality that is human trafficking.’

I haven’t seen it, but I am pretty certain that Cruz, Bannon and Trump don’t give a damn about Honduran children or any other children who can’t be useful to them politically. Because these are people whose concern for children is very selective. It doesn’t extend to ‘children in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, including foster care,’ ‘runaway and homeless youth’ and ‘unaccompanied foreign national children without lawful immigration status’, listed in the 2020 U.S Department of Justice report on ‘Trafficking in Persons.’

It doesn’t extend to the migrant children who were locked up in cages and taken from their parents and given to other families during Trump’s administration. Or the migrant children who are being denied water at the Texas border. Or the children who die week after week in American schools because of the country’s insane gun laws.

So the question is, why was Trump showing it and associating himself with it? The answer, and it isn’t rocket science, is that Trump is playing to the QAnon narrative of the child saviour in order to keep his base foaming at the mouth. Immediately after the screening, the Great Man promised to ‘end the child trafficking crisis by returning all trafficked children to their families in their home countries, without delay’.

No surprises there, but Trump also made a promise to introduce the death penalty to ‘anyone caught trafficking children across our border.’

This is where the love of children invariably takes these crusaders - to the gallows, the electric chair and the lethal injection. Because there’s nothing like a little capital punishment to make a certain kind of politician seem tough and caring. Both Trump and his would-be challenger Ron DeSantis have put the death penalty back on the political agenda, using child sex traffickers and child rapists as a pretext.

Because they too want to #Savethechildren and exploit whatever political capital they can get from the blood lust that inevitably accompanies both real and imagined crimes against children.

Let no one think there is anything uniquely American about this tawdry demagogic cynicism. In a country like the UK, punch-drunk from rightwing populism and its failed promises, and clammy with incipient fascism, it was inevitable that the monstrous crimes of Lucy Letby would be exploited by exactly the same people who have exploited so much else these last few years.

In little more than twenty-four hours after the verdict, GB News had called for at least twice for ‘debates’ on whether the death penalty should be brought back. Elsewhere, fascistoid numbskulls like Brendan Clarke-Smith and Lee Anderson were also tightening their knuckles round an imaginary noose, and Peter Hitchens could be found boasting about the two executions he has already witnessed.

On GMB, the shrivelled husk-like visage of the sadly ubiquitous reptilian sado-pundit Andrew Pierce could barely contain a grin at the prospect of dragging prisoners out for sentencing in chains and a gag.

In the Telegraph, the insipid altar boy Tim Stanley called for a ‘proper debate’ on the death penalty. Even though he opposes it himself, Stanley still thinks we should ‘remain sympathetic towards the instincts surrounding calls for the death penalty, and wary of attempts to dismiss or suppress them.’

Why should we be sympathetic to anyone but the people directly affected by this awful crimes? And why should not dismiss people who get some vicarious satisfaction at the prospect of someone hanging from a rope? Because, according to Stanley, ‘the murder of a child, so innocent and vulnerable, sparks rage in normal people.’ And also, ‘the modern world, rejecting the doctrine of original sin, often operates in ignorance of people’s capacity for wickedness.’

One can picture Stanley kneeling by his bedside in a monk’s robe with his hands clasped and a beatific smile as he came up with those lines. And yesterday the Telegraph returned to the same subject with a piece explaining how ‘the debate around reinstating the death penalty has re-emerged’ and headlined with a reader quote that ‘ The death penalty is the ultimate act of justice and it should be applied to child killers.’

This ‘debate’ has only ‘re-emerged’ because the likes of the Telegraph see Letby’s atrocious crimes as an opportunity to engage in some reactionary back-to-the-future posturing. No one is calling for a debate about original sin or the death penalty beyond the scrapings of our political class, the rightwing press and the dregs of Twitter and the rightwing comments pages.

Once again, it would be easy to conclude that the only fault with people like this is that they love too much, but vengeance is the goal here, not justice. And the death penalty has always had a morbid ability to stir unhealthy emotions in a certain kind of right-wing voter who thinks that ‘prison is a holiday camp’ and we need a ‘deterrent’, even though, like flights to Rwanda, there is no evidence that hanging has ever provided any such thing, or that it would have stopped someone like Letby from carrying out her atrocious crimes.

The US-imported astroturf ‘student’ movement Turning Point UK knows this very well, and has tried to turn the death penalty into a genuinely rabble-rousing cause célèbre, with advertisements like this:

And these are the reasons that it gives:

-The death penalty gets justice for victims & their families.

- A rope is eco-friendly as can be reused.

- Execution is cheaper than housing the most evil criminals for life.

-The death penalty has 100% guarantee of stopping reoffending.

- The death penalty deters future crime.

Nice. And the vicious vulgarity of that second ‘reason’ really gives an insight into the new age of barbarity that these people would like to take us towards. In their world, forwards is always backwards. If they have to use the murders of children to get there, let no one think they will hesitate for a second.

But we don’t need to have a ‘debate’ about the death penalty. We know the reasons for and against it. That debate was won in 1965, when capital punishment was suspended, and confirmed when it was made permanent in 1965, and again when it was finally abolished for all crimes in 1998. Had that not been the case, the Birmingham Six would all have been hung, and so would Barry George, Stefan Stiszko, Judith Ward, and Sally Clark, and let no one think that Lee Rigby’s killers would have been deterred from doing anything.

We don’t need to revisit a debate that already took into account murders that were no less atrocious than Lucy Letby’s crimes.

The only thing that has changed is that the country has become crueller and nastier, and the right would like to make it nastier still. Because capital punishment is part of its emotional comfort zone, and it is intended to appeal to the same kind of people who want to use gunboats against migrants, put soldiers in classrooms, and all the other ‘tough’ things that they think make us better.

In this country, a flailing hard-right movement desperate for anything that can serve its interests has even more reason to go down this reactionary path when so many of its promises have gone up in smoke, and when it no longer has any limits regarding the type of voter it is prepared to appeal to.

Bringing back the rope is just one more ‘victory’ its more extreme fringes would like to win. At the moment, these demands are mostly clickbait. But don’t be surprised if the death penalty becomes another rightwing ‘culture war’ issue - perhaps linked to withdrawal from the ECHR.

It’s even possible to imagine a Conservative Party election promise to hold - ahem - a referendum on capital punishment, regardless of the fact that Margaret Thatcher - who believed in capital punishment, refused to this.

Nothing is really off the table in these deranged times. But when we see these hard-faced tough guys on our tvs and mobile phones calling for executions, gags and chains in response to crimes against children, we should remember who they are, and what they want, and feel the same disgust at their shameless exploitation of these crimes as we do towards the crimes themselves.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

August 14, 2023

Suella Braverman's Diary

Phew!

Sorry I’m a bit late to this, but protecting our borders and disrupting the business model of the evil criminal gangs that thrive on human misery is a full-time job. I mean really. And our national Stop the Boats week was even busier than most weeks!

Honestly, I was rushed off my feet! Literally, I hardly had time to catch a breath. But hey, I’m not complaining! Because the British people gave me a job to do, and I can tell Miss Yvette Cooper and Monsieur Macron and Frau Von der Leyen and the lefty lawyers and closet Remainers and woke do gooders that it’s a job I take very seriously!

But Stop the Boats week. I mean, gosh! What a week! Honestly, it was just Off.The.Scale! Busy, busy, busy, every hour God sent. Even on Sunday - the day of rest (I wish!) - we were ready to go with Bob’s edgy column in the Sun, spilling the beans on that dodgy so-called anti-racist lawyer helping Labour stop our Rwanda policy ( A great policy btw, which will totally stop the boats, and don’t let any woke civil servant tell you otherwise!).

The next day Bob was interviewed by lefty Remoaner woke radio presenter Andrew Castle and asked for the name of the lawyer. And of course Bob wasn’t going to fall for that ‘facts’ nonsense. I mean, come on. This is 2023!

Castle kept on nagging (what is it with these people?) but Bob’s lips were sealed.

So off to a flying start with a BIG win for us. Go us!

And that same day, we put the first so-called asylum seekers on the Bibby Stockholm barge, ( Total cost to the hardworking taxpayer, ONLY £1.6 billion over the next two years. Go us!). That was despite the lefty Fire Brigades Union and other do gooders whittering on about safety and fire risk and ‘floating Grenfells’ and inhumanity and blah, blah, blah.

Fingers in the ears. Altogether now. La, la,la, la,la.

Because I’ll tell you what’s inhumane. Putting Albanians up in luxury hotels with gyms, swimming pools, and smorgasbords while the hardworking British taxpayer can’t even pay his bills and has to go to a community pantry to make ends meet, that’s what.

Care4Calais? About time we had a Care4Britain! But we did it anyway! We got 15 so-called asylum seekers on board! Fifteen! Go us!

And if they don’t like it, they can eff off back to France.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Not that I would personally use that kind of fruity language. Mummy and Daddy didn’t raise me to do that. But our Deputy Chairman is a simple son of the soil who speaks honest home truths from his simple working man’s heart. And even if the tofu-loving wokerati might not deem it ‘politically correct’ to put it in quite those terms, Lee expressed the genuine hurt and frustration that the British people rightly feel at the illegals who have abused our warm-hearted generosity for so long.

Because we are a welcoming people. With a proud tradition of welcoming. But honestly, there is a limit. And now the people have said ‘Enough!’ And I understand their righteous anger at the do gooders and the bleeding hearts and the RNLI and the lefty woke lawyers who STILL managed to stop twenty illegals from boarding the barge by launching vexatious and politically-motivated appeals to ‘the law.’

I’m sorry, but as a former Attorney-General, I won’t take lectures on ‘the law’ from a bunch of lawyers. And as Alex Chalk said, we WILL be coming for them. But later, because there really is so much to tell!

On Tuesday, we got the headlines we wanted: ‘Tory fury as lawyers block migrants on barges’ (Express) and me (Go me!) ‘Suella: “I’ll wage war on crooked migrant lawyers” (Mail).

What I said.

And yes, we WILL be seeking a whole life tariff for any rogue firm found guilty of helping illegals perpetrate immigration fraud. Go us!

On Wednesday Bob was off in Turkey doing a fabulous deal with Erdogan’s border force to stop the evil criminal gangs that thrive on human misery long before they reach the Channel!

All this at NO extra cost to the taxpayer. Just a few million diverted from overseas development assistance funds, because let me tell you that stopping illegals and so-called asylum seekers from coming to stay in luxury hotels in our country IS development, and don’t let any do gooder tell you otherwise.

So go Bob! Go us! And especially, yay me!

And on Thursday, to show how well our Stop the Boats policy was working, 756 people crossed the channel in a single day - a record for the year so far! All of which goes to show that our strategy for tackling the evil criminal gangs that thrive on human misery is working really, really well.

Because imagine how many there would have been if we’d done nothing?

But I can promise you that these number WILL fall, once the illegals find out they’ll be staying in barges and not at Centreparcs or Radisson Blu. And when we can FINALLY start sending people to Rwanda. Or Ascension Island. Or Barren Island. Or the Okavango swamps.

Or really, wherever.

When that happens you’ll see how many of them want to come here! That’s my dream. It’s just like Martin Luther King’s dream, sort of. He wanted people eating round some table of brotherhood thingy in sweltering Mississippi or wherevs: I want to see thousands of so-called refugees locked up in a detention centre in a distant land no one cares about, thousands of miles away from our white cliffs, our bowling greens and cricket pitches, our village fetes, and our community pantries.

Because the hardworking British grafter has said ENOUGH. And we need to put OUR people first. And as for those 173,000 so-called refugees waiting for an initial decision on their asylum claim, we’ll get to them once we stop the queue jumpers.

But of course the do gooders are all crying ‘incompetent!’ and ‘not fair! And of course they’d like to put them all in luxury hotels instead of the barges that were perfectly ok for our oil workers and rough sleepers and other simple sons of the British soil.

Why? For the same reason they tried to stop Brexit. Because they hate our country. Because they are the enemy within.

Well I can tell the Remoaners carping on the sidelines ( Yes it’s sooo easy to criticize when you’re not doing anything yourself!) that I will NOT let this happen.

Fingers in the ear. La, la, la, la, la. Do I look like I’m listening? That’s because I’m not!

And then Friday. Of all the things! Some busybody goody two shoes discovers Legionnaire’s Disease in the water, and so we have to take the same asylum seekers off the barge who we put on it on Monday.

Can you imagine?

Well, who could have predicted that, without doing safety checks? Which we didn’t have time to do, because, come on! These are illegals.

And I am busy! Busy, busy, busy.

And it’s not as if any of them actually caught Legionella, (a minor ailment, compared with Ebola, fyi). So really, a lot of fuss about nothing. Health and safety gone mad. And how did that Legionnaires Disease get in the water supply, that’s what I’d like to know?

Bit too much of a coincidence, if you ask me.

Because let’s face it, if you’re going to come here without permission you need to know that you’re not going to be living the life of riley on a bed of roses, whatever the Labour Party and Miss Yvette Cooper and all the virtue-signalling humanitarians will tell you.

And we WILL sort out the barge and put the illegals back on it, and those who don’t like it will just have to suck it up.

Anyway. Despite these little blips, the week was going really, really well, all things considered. And then on Saturday, what happens? Six so-called Afghan refugees go and drown in the channel! Just like that!

Well awful. Just awful. And of course my thoughts and prayers go out to them, and this is why we have to fight the evil criminal gangs that thrive on human misery.

But let’s not lose a sense of proportion! It’s not as if anyone made these people cross the Channel. It’s not as if they weren’t already in a safe country.

Perhaps if the French had done their job properly, instead of punishing us for leaving the EU and shipping their unwanted so-called refugees over here, these unfortunate people might not have taken such a risk and paid all that money to the evil criminal gangs who thrive on human misery.

So thoughts and prayers. Should go without saying. But just in case, I’m saying it.

There. Done.

Not that it makes a blind bit of difference! Because people will moan, won’t they? And now the do gooders and the bleeding hearts are bleating on again about ‘alternate safe routes’ and ‘blood on our hands’.

Well let me tell you, there is NO blood on MY hands. And I won’t take lectures on human decency from a bunch of humanitarian charity workers who do nothing but try to help vulnerable people. I sleep soundly, in the little shuteye that I’m able to snatch, because delivering for the British people is a full time job! 27/7!

And I can tell you that I will not reward people who seek to enter our country illegally by allowing them to enter it legally. Because really, what do they want us to do? Fly every so-called victim of Taliban oppression in from Kabul so they can stay at the Hilton?

Why not roll out the red carpet? What do they want? Golden elevators? Jacuzzis? Pampering days?

I say, NO.

I say, what’s wrong with France?

And I will fight these invaders. In the mountains and on the beaches. I will never surrender.

Read my lips: I. Will. Stop. The. Boats. And if the do gooders and the traitors try to stop me, I will work to ensure that we have a Tory government that can send these people back to where they came from, and THAT is the issue we will fight the next election on.

No ifs. No buts.

And I don’t care if we have to leave the ECHR and the United Nations and the Geneva Convention and all the other ‘laws’ and multilateral conventions that the global elite drew up after World War 2 or whenever, and thinks we have to obey now.

I’m sorry, but we didn’t leave the European Union for that. We didn’t win back our sovereignty and independence for that. We didn’t defend it against the Remoaner traitors for that. And I say to all the do gooders, the bleeding hearts, the lefty lawyers and the charity hustlers.

We ARE coming for you.

We WILL put illegals back on that barge.

We WILL stop the boats.

We WILL disrupt the business model of the evil criminal gangs that thrive on human misery. And if we have to surround the country with a sea wall and barbed wire like that lovely Greg Abbott did in Texas, fine. And we WILL make France and the EU pay for it, and they will just have to suck it up.

Because we ARE a GREAT NATION.

And we WILL win the next election by drawing a line in the sand between those who LOVE our beautiful country and those who HATE.

That’s all for now. Must rush.

Busy. Busy. Busy.

Yay me.

August 10, 2023

Woke Up This Morning

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0.It’s always a good idea to recognise the strengths of your political opponents, and there are two things that the new populist right does very well, which go a long way to explain its political successes in the last few years. The first is lying. Unencumbered by any moral scruples or concern with even the most elementary notions of truth that make it possible for a democracy to function, its representatives feel able to say anything, regardless of whether it bears any connection to reality.

The second - closely related to the first - is the right’s ability to make its intended constituencies feel like victims, to the point when they believe that they are being subjected to vast conspiracies that threaten their very existence.

Both these talents converge seamlessly in the right’s ongoing obsession with ‘woke’, ‘wokeism’ and ‘wokeness.’ Nowadays, in the English-speaking world at least, you would have to go into a cave with a blindfold and ear plugs on to avoid coming across one of these terms at least once a week.

Where there used to be reds under beds, there is now rampant wokey pokery operating in every sphere of society, trashing our history and identity, dismantling our institutions and most cherished beliefs, insinuating itself into the minds of the unwary like the alien seed pods from Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Woke lefty lawyers; woke civil servants; woke schools and teachers; woke weathermen; the woke National Trust; the woke Labour Party; woke Costa Coffee shops - it’s everywhere.

Even the elite royal bank Coutts is now woke. And so is the US women’s football team, according to Donald Trump, which is why it lost. And the Bannau Brycheiniog National Park Authority is also woke because it changed the name of the park to Welsh. Last week, the Daily Mail - an authority on all things wokeist - published its ‘Woke List 2023’ of the ‘Britons who are most high-profile in their awakedness to perceived injustices in society.’

That ‘perceived’ is the crucial word here, and the list was not intended as a badge of honour. Its luminaries include the Archbishop of Canterbury, Gary Lineker, the Director-General of the National Trust, the Chief Librarian of the British Library, the ‘ungrateful, woke brat’ Emma Watson, Michael Sheen, the ex-Chief Executive of NatWest Group, and the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

Traitors, bastards, and useful idiots, the lot of them. And the Comintern can eat its Stalinist heart out, because this is what it really means to take over a society by stealth.

Political CorrectnessAt first sight, all this wokeus pocus recalls the concept of ‘political correctness’ which first emerged in the seventies and eighties as an in-joke amongst the left, and went on to become an insult used by the right to ridicule the left and the causes and issues associated with it.

To say that such and such a person or institution was ‘politically correct’ automatically suggested inauthenticity, a lack of seriousness, and an obsession with marginal issues. To be ‘politically correct’ meant that you didn’t really believe in any of the causes you espoused; you were merely trying to live up to some fatuous leftist nostrums in order to make yourself feel good and look good.

Even worse, you were trying to make other people look bad, by imposing limits on free speech on the everyday good folk who just wanted to watch the Black and White Minstrel Show and exclaim ‘what a pair of knockers!’ without having to feel guilty about it.

Accusations of political correctness invariably tended to crop up in the context of discussions about racism, sexism, the discrimination of minorities, and so on, and were often used in tabloidspeak in reference to ‘loony left’ city councils and the ‘political correctness gone mad’ stories that abounded in the era of municipal socialism.

These were the days when the Murdoch papers gleefully churned out stories about bans on black bin liners, about primary school kids forced to sing baa baa green sheep, and everybody had a larf at the Citizen Smiths and the do good zealots with their wacky lefty schemes. The term also became a standard element of mainstream discourse, always with the same nudge-wink, shake-your-head pitying irony, and often accompanied by attempts to praise those few free thinkers, like Alan Clark or Jim Davidson, who were supposedly brave enough to break the ‘rules’.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Of course, there is no reason why the left can’t be mocked. Leftists aren’t immune to intolerance, holier-than-thou pomposity, hyper-orthodoxies, dogma, and authoritarianism. But these accusations of ‘political correctness’ were not seeking to make the left behave better, but to discredit the causes that it stood for.

As a delegitimizing strategy, it was quite effective. It encouraged the kind of cynicism that the right thrives on, and it also encouraged the mockery of very real social injustices and forms of discrimination, which still persist today. Traces of this past can still be found in the contemporary right’s obsession with ‘woke’, but whereas political correctness was depicted as a ridiculously overzealous response to ‘perceived’ social injustices, ‘wokeism’ is imagined as something far more sinister and dangerous.

Consider some of the books that have been written about it in the last few years:

How Woke Won: The Elitist Movement that Threatens Democracy, Tolerance, and Reason; Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America; Woke Antisemitism: How a Progressive Ideology Harms Jews; Woke Culture: Working to Destory Our Nation; We Speak for Outselves: How Woke Culture Prohibits Progress.

You get the idea. In 2021 the Sun published a piece on how ‘“political correctness on steroids” and woke-weaning betrays and brainwashes children’.’ One of its interviewees was a History professor who compared student policy on ‘microaggressions’ to the Inquisition. Another retired headteacher insisted that ‘every area of school life is determined by wokeism. There is no dissent. It’s like religious, totalitarian fanaticism.’

Reading such pieces, you can’t help wanting to send some of these interviewees to a country where there really is ‘religious, totalitarian fanaticism’ in order to re-acquaint themselves with reality, but reality is not the point here.

In May this year, wokeness appeared in many of the speeches at the London ‘National Conservative’ conference. For flat-out idiocy, it was hard to beat the Tory backbencher Danny Kruger’s shrill warning about ‘The weird medley of transgressive ideas that is now threatening the basis of civilisation in the West.’

This medley doesn’t come much weirder than Kruger’s evocation of ‘a new ideology, a new religion – a mix of Marxisim and narcissism and paganism, self-worship and nature-worship all wrapped up in revolution.’ Nevertheless, he insisted,

they are wrong and they are a lethal threat. Because to build their new Jerusalem – their pagan city on a hill – first the old one must be destroyed. Everything must be undermined. Dismantled. Swept away.

Everything must conform at last to the imagining of John Lennon: No countries. No families. No religions (except this one). Nothing to live or die for. No history, just a bland progressive present.

So… Jerusalem is pagan now? And never mind that Lennon sang ‘Nothing to kill or die for’ - a very different message - because this is the heady brew that makes new conservatives heads swim, and whatever they’re snorting in the HoC these days must be stronger than we realize.

This was one of the first occasions anyone has heard anything from Kruger, which on the evidence, can only be a good thing. But talking like this can get you invitations to some very rightwing places you wouldn’t otherwise get to. This is why perennial Tory mediocrity Oliver Dowden took off to Washington in February last year to lecture the palaeoconservative Heritage Foundation on the ‘painful woke psychodrama sweeping the West.’

The Heritage Foundation doesn’t need much convincing. After all, this is a thinktank that has always been adept at pushing very hard right messages into the American mainstream, and its website teems with articles on wokeus pocus and wokery, such as the following explanation of its origins:

The term does come from black slang, and according to Vox (the authority on all things woke), it meant “the notion that staying ‘woke’ and alert to the deceptions of other people was a basic survival tactic.”

Then white leftists, feeling guilty about crimes they never committed, borrowed the term (or “culturally appropriated” it, if you believe the woke nonsense) to denote a consciousness of the supposed social injustice that is part of the very tapestry of the oppressive nature of American society.

Or some such. The initiates into the woke cult are intravenously fed this propaganda about a systemically racist and oppressive America to provoke them into dismantling society and the entire system.

At a time when the left can barely win an election anywhere in the world, it may be comforting to imagine that the ‘woke cult’ is capable of achieving such momentous outcomes. One of the recurring threads in anti-wokeism, is the idea that the left - a word which pretty well refers to anyone across the broadest of leftist-liberal spectrums - has abandoned its efforts to take formal political power in favour of ‘cultural activism’ and the ‘long march through the institutions’ strategy advocated by Gramsci, Rudi Dutschke and Hans Magnus Enzenberger.

According to the Australian conservative Dr Kevin Donnelly, ‘Woke identity politics is a radical attempt by the cultural left to remake Western society in their image.’ Like many anti-woke ideologues, Donnelly builds this sinister ideology/conspiracy from a disparate array of sources, from the Frankfurt School, to Gramsci, Marcuse, the 1968 Paris riots, and the ‘hippy, counter-culture movement.’

Such claims are difficult to take seriously, because there is really no coherent evidence than any such unity exists, or ever really has existed between all the elements included here, even if the right likes to believe otherwise.

Why is this happening? On the one hand, anti-wokeism is a new variant on an old rightwing technique: the evocation of a fantasy conspiracy in order to discredit your opponents or anyone with a different worldview. At the same time it’s a very specific response to the rise of ‘identity politics’ and cultural politics, to ‘cancel culture’, the Black Lives Matter movement, Me Too feminism and the ongoing and often toxic debate about gender and trans rights.

There are certainly legitimate criticisms that can be made, and reservations that one can have about the way some of these ‘new’ movements conduct themselves, and whether or not some of them represent a regression from ‘universalist’ principles that define the left at its best.

But these aren’t the criticisms that the right is making. Once again, its aim is not to create a better left, but to destroy the left, through the construction of a fantasy ideology-cum-conspiracy that is not nearly as powerful or as unified as the right proclaims.

A Culture of CrueltyAll this is extremely dangerous, because antiwokeism dismisses, delegitimizes and often demonizes very real injustices and problems, in an attempt to prevent any solution to them. In doing so, it shores up the most reactionary, conservative, and often downright fascistic sections of society, to the point when even the climate emergency and clean air policies can be dismissed as just another expression of wokeness.

It’s amazing how readily anti-wokeists will pivot to Great Replacement theories and antisemitic ‘Cultural Marxism’ conspiracy theories; how the likes of Miriam Cates will be warning of ‘woke teachers’ who ‘destroy our children’s souls’ one minute and then depicting falling birth rates as a cultural threat to the UK. One minute anti-wokers will be telling you ‘women don’t have penises’, the next we’re heading towards Lebensborn.

In effect, anti-wokeism has become a weapon in a different kind of majoritarian ‘identity politics’, which is attempting to roll back liberal social gains, postpone any discussion about structural racism and sexism, and shut down debate about how to create a more just, equal and diverse society.

It’s actually a good idea - in fact an essential idea - for any society that wants to be better than it is, that its members should be aware of the injustice and oppression that society may be perpetrating, and show solidarity with those who have been victims of such injustice.

The alternative to that is grim indeed. Ron DeSantis has made it a hallmark of his sordidly opportunistic career to define Florida as a place where ‘woke comes to die.’ His anti-woke regime has reportedly lost his state billions of dollars, not because ‘the left’ has taken it over, but because corporations and investors see no future for their brands in associating themselves with reactionary bigotry.

None of this bothers the ex-Guantanamo guard. Fresh from promising to start ‘slitting throats' if he becomes president, DeSantis has now supported the use of ‘deadly force’ by special forces and border officials against drug traffickers crossing the Mexican border

Asked how these operations could distinguish between traffickers and migrants, anti-wokeism’s answer to Steve Seagal said that they should use US military operations in Iraq as an example.

In Texas, fellow anti-wokeist Governor Greg Abbott shared a fake article about country singer Garth Brooks being booed off the stage in a purported display of patriotism in response to the singer’s perceived wokeness in a non-existent town called ‘Hambriston’. In July Texas troopers employed by Abbott’s border control initiative reported that they had been instructed to deny water to migrants crossing the Rio Grande and push women and children back into the river.

These connections aren’t accidental. Because this is where anti-wokeism leads: to performative demonstrations of cruelty. To denying water to migrant children. To putting migrants on barges or sending them to Rwanda. To politicians telling asylum seekers to ‘fuck off back to France.’

In short, it makes society crueller and meaner. So best not to give into it. Better to stay woke and call out injustice when you see it. Better to lend your back, and your voice to the idea that the world is not as bad as the likes of DeSantis, Abbott, and Anderson would like it to be.

Better to feel not shame, but pride, when they call you woke, and think that you are probably doing something right.

August 5, 2023

Trump's Last Battle

Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore

Photo Credit: Gage SkidmoreOn the surface, it’s not been the greatest of weeks for Donald J. Trump. It isn’t every day that a former president of the United States finds himself indicted on four separate federal charges, including conspiracy to defraud the government and obstruct the electoral count during the 2020 presidential election, with another indictment likely to follow pertaining to Trump’s machinations in Georgia.

This follows 37 charges in June relating to Trump’s handling of classified docs, and a $250 million law suit from New York attorney general Letitia James against Trump and three of his children. This is enough criminality to make Watergate look like a minor traffic infraction in comparison.

It’s all looking a bit grim for the Emperor of Mar-a-Lago, or at least it should be. This really ought to be the moment - belated to be sure - when the scales finally fall from the eyes of all but the most corrupt , the most depraved, and the most manipulated of Trump’s supporters; when the politicians who finally jump off his bandwagon scattering mea culpas for the monster they created.

But 2023 is not 1972, and the baseline threshold of acceptable political behaviour in the United States long ago collapsed like so much rotten wood under the weight of monstrosities who make the Nixon era look like a golden age. And even though Trump has been indicted for grievous crimes against American democracy, millions of Americans with eyes are not willing to use them, or will only see what they want to see.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

No one can be surprised to find Trump boasting of the indictments as a ‘badge of honour’ or describing himself as a victim of political persecution comparable to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. This is what he will always do, but he isn’t the only one.

Polls show that Trump’s support within the Republican Party actually increased following Jack Smith’s indictments. As a presidential nominee, Trump is miles ahead of his nearest challenger, the absurd coward Ron DeSantis. Some polls for the 2024 election have him tied with Biden on 43 percent, while others give Biden a 44 percent lead.

Don’t these voters have a moral compass? The answer to that would be a resounding no, at least not when it comes to Trump. After all, these voters include people who believe that the rapacious pussy-grabbing sociopath is Jesus Christ, or at least that he has Jesus’s ear, like the supporter on the Gab social media platform who responded to Trump’s arrest this Easter with the observation ‘Seems there was someone else who was tortured and crucified.’

As another supporter on Telegram put it that same month: ‘Good vs. Evil. Biblical times. Divine timing.’

The least that can be said about such comments is that they lack empirical rigour. But then so do the QAnoners who believe that Trump is fighting a cosmic battle to save children from being raped and eaten by Hilary Clinton and Celine Dion in order to drain adrenochrome from their brains. And the Twitter trolls who posted pictures of Jack Smith as the ‘face of evil’ over the last week. Or the politicians like Sarah Palin and Marjorie Taylor Greene who believe that the Democrats are ‘communists.’

You’re not going to get much sense or honesty from these quarters, and certainly no repentance. Politically-speaking, this is the twilight zone, where a June Reuters/Ipsos poll found that nearly 70 percent of Republicans believe law enforcement officials are engaged in ‘politically motivated investigations’ against the former president, and another poll in March found that 58 percent of Republican voters still believe the 2020 election was ‘rigged’.

In effect, the entire Republican Party is infected with TDS (Trump Derangement Syndrome'), and this is why the likes of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy - a man who would pimp his own mother for political advantage - are working themselves up into a lather of fake-indignation, echoing Trump lawyer talking points that the former president was merely exercising his right to ‘free speech’ by challenging the 2020 election results.

In fact, the indictment goes to some lengths to point out that this was not the case, and that Trump is not being charged for expressing his opinion, but for actively colluding and conspiring to undermine the election, thereby denying American voters their democratic rights.

McCarthy et al are too co-opted, too craven or too self-interested to care less. As long as the base sticks with Trump, they will stick with the base. And DeSantis is no better, simultaneously trying to distance himself from the ‘rigged’ 2020 election narrative while also describing the indictments as politically-motivated.

Some more hopeful polls this week suggest that 52 percent of Republicans wouldn’t vote for Trump if he was in prison on election day, and that nearly half of Republicans wouldn’t vote for him if he was convicted. This is hardly the stuff of political happy endings.

‘If’ is the key word here. Should Trump’s lawyers succeed in delaying his trials, he could win the election and then pardon himself. And even if he is convicted and ends up in jail before the election, it’s entirely possible that some Trump-surrogate like DeSantis could run on a ‘pardon Trump’ ticket and do just that.

From Trump’s point of view, he has to become president to stand a chance of staying out of jail, and if he achieves these aims, he has made it clear that he intends to inflict ‘retribution’ on those responsible, in messages like this deranged post on his Truth Social platform:

A Trump spokesperson has since issued a statement defending the former president’s post, as ‘ the definition of political speech, and was in response to the Rino [Republicans in Name Only], China-loving, dishonest special interest groups and Super Pac’s.’

Few people are likely to be fooled, except those who want to be. And in order to understand what Trump might do in order to win, and what he might do if he does win, it’s worth taking a closer look at the way he has depicted his enemies.

The Deep StateLong ago, back in the late sixties and early seventies, the concept of the ‘deep state’ was used by the left to refer to the ‘strategy of tension’ pursued by elements elements within the Italian state, who appeared to be colluding with both left and right week terrorism in order to push Italy towards an authoritarian democracy.

Today, this imagery of puppet-masters working in the shadows has become a recurring theme in the right’s neo-gnostic view of the world, to describe any opposition to anything the right wants to do, whether legal or political, and any attempts to indict or discredit Donald Trump. In July 2018, Kevin McCarthy - of course - described an anonymous op-ed critical of Trump published in the New York Times as evidence of a ‘permanent political class in Washington that believes that it has a divine right to rule the American people. You could even call it a Deep State.’

You could, though if you had even a smidgeon of honesty and integrity, you probably wouldn’t. No surprise then to find Lindsey Graham in November 2019, responded to revelations that Trump extorted the Ukrainian government for political gain with the observation ‘When you find out who is the whistleblower is, I’m confident, you’re gonna find out it’s somebody from the deep state.’

Such discourse will not be unfamiliar on this side of the pond. In February 2018, a number of Brexiters accused the Treasury of having ‘fiddled the figures’ to make post-Brexit economic assessments seem worse, such as the the ex-Brexit Minister David Jones, who warned that ‘ the last of the Remain tendency are deep within the bowels of the Treasury.’ The Treasury’s negative assessments also moved Jacob Rees-Mogg to wonder ‘if there isn’t a pattern in that, whether there is some orchestration of the stars.’

If the Deep State can orchestrate the stars, it can also bring down prime ministers, according to the indefatigable truth-teller, Dan Wootton at GB News, who described the Privileges Committee investigation into Boris Johnson’s rule breaking as an ‘anti-democratic campaign…that threatens to undermine British democracy itself…The deep state stitch up of Boris Johnson could have ramifications for our political system…the stakes could not be higher.

Blessed is the nation that has such democrats to defend its institutions. In the UK the sinister references to the Blob’ and the ‘Deep State’ have been used to justify attacks on the civil service, and Donald Trump has a surprisingly similar agenda. One of his last acts before the 2020 election was an executive order moving federal workers in ‘confidential, policy-determining, policy-making or policy-advocating’ civil service jobs into a new job classification, which would make it possible for the government to remove and appoint government employees at will.

As Trump described it in a rally that year, these were ‘ critical reforms making every executive branch employee fireable by the president of the United States,’ in order to ensure - wait for it, that ‘The deep state must and will be brought to heel.’

This order was rescinded by Biden, but Trump has never abandoned these aspirations. In March this year he told a rally that if re-elected he would remove parts of the federal government in order to ‘totally obliterate the deep state.’ This, he insisted, was ‘the final battle…Either they win or we win.’

It’s clear why Trump must win this ‘battle’. But many of his supporters are so afflicted with TDS that they see the world in exactly the same terms as he does. They believe that Trump is the victim of a ‘deep state’ plot, and even if they don’t believe it, they will pretend to, as Ron DeSantis did this week, when he promised to transform the federal bureaucracy through mass firings, in which he would ‘start slitting throats on Day One.’

DeSantis has been widely condemned for using violent language. But violence is a very real possibility, whether Trump wins or loses. And if he wins, and attempts to replace 50,000 civil servants with his own appointees, this will not be an attack on the Deep State or a ‘critical reform’ of government.

It will be an act of vengeance, and an authoritarian power grab by a criminal and would-be tyrant that would spell the end of American democracy, and send a dark message across the world.

And the great problem that America - and the world - now has, is that millions of people know this, and don’t care.

July 29, 2023

Boil, Baby, Boil

Fictional dystopias are often intended as warnings to the present. In imagining the worst possible future, they tend to extrapolate the most dire possibilities from present trends, acc-ent-u-at-ing the negative to show what we could become if we don’t watch out. The twenty-first century has been a golden age for fictional ‘black mirrors’, and it’s difficult to separate this seemingly endless appetite for apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic end-of-world scenarios from the very real dystopian turn of 21st century politics and society.

Shadow wars against an omnipresent terrorist enemy; Islamic State’s murderous utopias; the insane corruption of the Trump presidency; QAnon and the January 6 insurrection; the Covid pandemic; the weekly massacres of refugees in the Mediterranean; the denial of water to pregnant migrants at the Mexico-Texas border - these are only some of the routine ‘already existing dystopias’ of our era that would fit comfortably into any fictional realisation of the worst possible future.

But the most alarming manifestation of our current dystopian turn is the calamitous degradation of the natural world as a result of human activity, whose consequences are increasingly impossible for all but the wilfully blind to ignore.

Take the events of last week. On 24 July CBS News reported that preliminary experiments were taking place in the Florida Keys to assess whether sharks may be becoming addicted to cocaine, because of the amount of cocaine that has ended up in the ocean. I wasn’t aware of this before. Nor did I know that brown trout and other fish had become addicted to methamphetamine.

Call me humourless, but I’m not laughing at these wired ‘cocaine sharks’. Because human beings might ‘choose’ to be become addicts , but sharks and fish shouldn’t have late capitalism’s throwaway toxins foist upon them, and the fact that this is happening is another indication of the seemingly limitless and increasingly grotesque human alteration of the natural world.

In the same week the wildfires in Rhodes and Corfu provided another reminder of that transformation. Media coverage of the fires focused mostly on the novelty of tourists-turned-climate refugees fleeing from ‘nightmare holidays’ , producing a stream of images that would not have been out of place in a JG Ballard novel.

Women in swimming costumes, summer dresses and glamorous sunglasses speaking into mobile phones; lines of tourists in shorts and sandals dragging pullalong bags away from the red Brueghelian sky; evacuees clustered round beach huts beneath billowing clouds of black smoke; gyms and schools turned into makeshift shelters for stranded tourists - these were some of the pictures that made the front pages over the last seven days.

The Greek government claims that most of these fires were man-made, which may be true. But the reason they have spread is because we are now living through the hottest summer on record - hotter than the previous record last year - in which everything is drier than it should be and ready to burn.

So far wildfires have broken out in Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, and Spain. In Sicily wild fires forced the closure of Palermo airport and temperatures in Catania reached 47.6 C - making the air so hot and polluted that even breathing has become difficult. In Milan a heatwave turned into a freak hailstorm across Lombardy that sent slabs of ice flowing through a nearby city.

These storms took place after what had already been the hottest July in recorded European history, in which sea temperatures have also reached new records. The World Meteorological Organization has had no hesitation in attributing these developments to human activity. Nor has UN Secretary-General António Guterres, who announced this week that ‘The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.’

As if this wasn’t bad enough, the journal Nature Communications published the results of a study from the University of Copenhagen suggesting that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc) which carries warmer water from the tropics to western Europe may slow or ‘shut down’ within the next decade as a result of climate change - a transformation that would make Europe colder and much of the rest of the world considerably hotter.

‘He who laughs has not yet heard the bad news’, Bertolt Brecht once wrote, but that is a lot of bad news for one week, and it ought to be a wake up call, except that so many dire wake up calls have already come and gone, without producing anything like the commensurate response.

You sometimes hear the sinking of the Titanic as an analogy for our current predicament, but unlike the Titanic, we can clearly see the multiple catastrophes coming towards us. We’ve been warned again and again, decade after decade, about the damaging impact of fossil extractivism, about the human impact on animals, about the threats to our survival as a society and even as a species.

Scaremongers and ‘Climate Scams’We know what a climate change dystopia looks like, and what ecological collapse could look like, because so many people have spelt in out in great detail, and because so many of the things that were predicted many years ago have already started to happen. We also know the potential solutions, policies, and mitigating steps that we could implement to try and prevent these outcomes.

Yet here we are, in July 2023, staring into the ‘age of boiling’, and it’s not even August. Of course if you believe some people - and I highly recommend that you don’t believe them - none of this is really happening. For the last week now the hashtag #ClimateScam has coursed through Twitter, boosted by armies of bots and amplified by the usual suspects. In Sicily, the holidaying Julia Hartley-Brewer, could be found tweeting with her characteristic joyless gleeful malice:

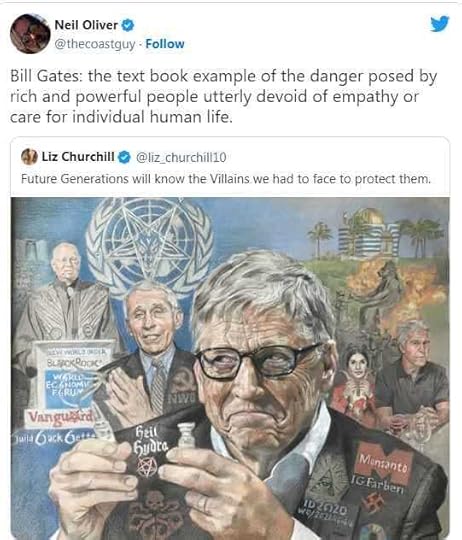

Elsewhere, David Frost (again…sigh) informed the House of Lords that rising temperatures were likely to be ‘beneficial to the UK’ because more people die from cold than hot weather. At GB News, Neil Oliver accused the BBC and other ‘woke’ weather presenters of ‘scaremongering’ and generating ‘fear of the summer’ by using satellite images of ground temperatures to make it appear that the regions described were hotter than they were.

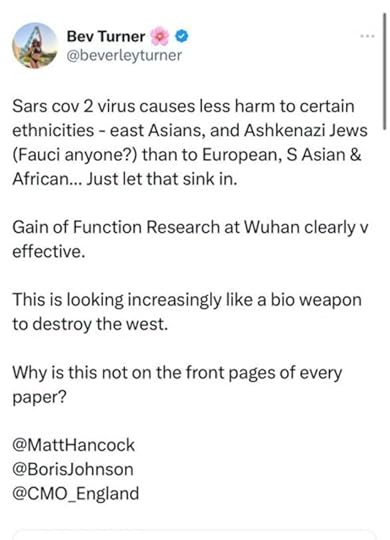

This was not true - weather maps are not designed on that basis, and Oliver’s claims were immediately and comprehensively debunked, but not before at least two million people had seen his video on social media. Why are ‘they’ frightening people? Because, according to the gimlet-eyed Thane of Mordor, ‘they’ want ‘to get control of people again’ just as they did with Covid. This is why images like this have been circulating on social media, parodying media ‘scaremongering’:

It would be easy to ignore such stupidity, and certainly better for anyone’s blood pressure, were it not for the damage these ‘climate change denialists’ do, and the amount of people they reach and try to reach - often with considerable financial support from fossil fuel companies and billionaires with far more to gain from the propagation of such views than the ‘woke’ BBC has to gain from instilling ‘fear of summer.’

Some of these people will be the kind of voters who rejected Labour in protest at Sadiq Khan’s (Ultra Low Emissions Zone) ULEZ policy, and the kind of voters who Sunak’s Conservatives and - to a lesser extent - Labour itself are now courting as they row back from the policy they once supported, and retreat from climate change mitigation in general.

While there may well be valid criticisms that can be made of this policy in terms of its impact on low-income travellers, it’s only through policies like these that we will have a chance of making our cities healthier places to live in, and stave off the catastrophes that may otherwise become uncontrollable and unstoppable.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

We need to understand that we are not separate from nature, but an integral fleshy part of it, and that we are now the custodians of the planet on which our survival depends. ‘Numberless are the world’s wonders and none is more awe-inspiring than humanity,” wrote Sophocles in Antigone many centuries ago. ‘This thing that crosses the sea as it whorls under a stormy wind/finding a path on enveloping waves/It wears down imperishable Earth, too.’

The earth may be imperishable, but it can be made unfit for human life and for many other forms of life, and humanity will not be so awe-inspiring if we allow our common home to become an overheated desert, and cannot find the collective will to do something to prevent it when we still had had the chance to.

To call this a tall order would be something of an understatement, and we need to recognise the possibility that we may fail to pull it off. It is possible that the stupid, the dishonest, and the selfish streak that runs through humanity - supported by social and political structures that have no interest in humanity becoming anything else - may prove to be more powerful than the proactive development of collective responsibility for the damage we have already done and may yet do.

Because if we walk - not even sleepwalking but with eyes wide open - into the ‘age of boiling’, then it won’t matter that humanity once produced the likes of Bach, Hendrix, Shakespeare, George Eliot, Picasso, Buddha or Rosa Parks, because all the great men and women, and all the geniuses, and all the expressions of ordinary humanity that distinguish our species at its best will not have been enough to save us from humanity at its worst.

If we fail, then it won’t matter who we loved or what we cared about, and what kind of world we wanted our children and grandchildren to live in. It will mean that we have succumbed to the worst of us, and listened to the worst of us, and voted for leaders who could not be bothered to save us. It will mean that the history that nineteenth century bourgeois scientists once believed was based on progress and the pursuit of perfection was in fact the tragic story of a species that was smart enough to dominate the planet but not smart enough to save it.

Last year William Shatner - the original Captain Kirk in Star Trek - wrote movingly of his first trip to real rather than fictional space at the age of 90. Shatner described the contrast between the ‘feeling of deep connection with the immensity around us, a deep call for endless exploration’ that he expected to feel, and his ‘deepest grief’ ‘contemplating our planet from above’:

What I understood, in the clearest possible way, was that we were living on a tiny oasis of life, surrounded by an immensity of death. I didn’t see infinite possibilities of worlds to explore, of adventures to have, or living creatures to connect with. I saw the deepest darkness I could have ever imagined, contrasting starkly with the welcoming warmth of our nurturing home planet.

We don’t need to go to space to understand that ‘welcoming warmth.’ We witness it every morning when we wake up and draw back the curtains; when we turn out the lights at the end of the day and close our eyes to sleep. We can see it when we go for a walk in our local park, when we go to the beach or the mountains, when we feel the rain and cold; when we watch the delight with which children respond to the world in which they find themselves.

We need to save all this - for ourselves and for others, and for those who come afterwards. We need leaders who can help us save it. We can’t accept any other kind. No ifs. No buts. No postponements or adjournments. No more fetishization of ‘growth’.

No one can say this will be easy. There are powerful vested interests that will do everything to prevent such action, or simply seek to sow enough seeds of doubt to encourage inaction. No species has ever been required to take collective action like this, because no species has ever been in the position in which we find ourselves - masters of the planet and yet still dependent on it even as we contribute to its ongoing ecological collapse.

Yet during the Covid pandemic we showed - up to a point - that we can act collectively to save ourselves, that we can cooperate and make sacrifices for the common good.

The climate emergency requires the same urgency, and the same levels of planning, foresight, and cooperation.

It’s so much easier to do nothing, and tell ourselves that nothing needs to be done, or that nothing can be done. But if we succumb to inertia or self-interest, or despair, we will find that the ‘already-existing dystopias’ of the present are just the beginning.

And at the risk of sounding ‘scaremongering’ or inducing ‘fear of summer’, it’s worth pointing out that dystopian dramas may make for riveting Netflix series, but we will not want to be spectators of the real eco-dystopias that may be just around the corner.

July 20, 2023

Waiting for the Foxarians

I’ve always had a soft spot for the BBC. It probably started with Hector’s House, Z Cars, and The Magic Roundabout. Or the Play for Today and the Wednesday Play, which hosted some of the most original and cutting edge drama that has ever appeared on television.