Matthew Carr's Blog, page 14

June 21, 2023

The Farce of the Red Death

Government, in a democratic country at least, is a serious and sober business, or at least it should be. I mean seriousness and sobriety should be qualities that every elected government should aim for, regardless of their political persuasion. Never having been in government myself, I can only make this observation from afar, but that is the position that most of us will ever make such observations from.

Such distance is built into democracy. In a country like the United Kingdom, with a population of sixty-seven million people, many of whom do not and never will think alike, we vote for politicians from a long way away, and hope or believe that the trust we have been placed in them will be repaid by truth, honesty, and at least an attempt at competence, coupled with a willingness to admit that mistakes have been made and rectify them if possible.

I recognize that this is only an ideal, and it isn’t always achieved. I remember very well the speech that Tony Blair gave to the House of Commons in March 2003, when he defended the invasion of Iraq that had already been decided upon, with the characteristic veneer of seriousness that concealed the essential shallowness and recklessness of the entire undertaking. Blair, like Anthony Eden before him, may well have believed his own lies, or at least rationalised them to himself as necessary instruments of raison d’état.

We will all have our own particular memories of moments when such trust was breached, or when we believed it was. And yet there was a time when even the shadiest politicians were expected to pay lip service to this ideal, regardless of whether they always lived up to it. Because without it, the whole basis of democratic government collapses.

Why would you vote for a prime minister who you know is lying, not only to you, but to the democratic institutions intended to hold the executive to account? Isn’t this why parliament exists? And would the point of democratic politics even be, if anyone could lie at any time, to whoever they wanted, and never pay a price for it?

Once again, I recognise that there have been occasions when politicians have lied and have got away with it, and yet I insist that trust and trustworthiness remain as essential ideals, without which, even halfway decent government becomes impossible.

I say this, at a time when the single greatest liar in British history has finally been forced to stand naked, as Bob Dylan once put it, and not in his own or someone else’s bedroom, but in full view of the country that he treated with a contempt unmatched by any other prime minister.

Sometimes good or simply halfway decent politicians are undone by circumstances outside their control, which lead them to take poor decisions taken in the midst of wars, invasions, financial crises and so on. It’s entirely fitting that Johnson was undone not by the unexpected turn of historical events, but by precisely the qualities on which his entire career was based: the ability to lie, cheat, distract and deflect.

Many people have known this for a long time, and too many chose to ignore it. In the early nineties Johnson lied about the European Union to create a political identity for himself as a maverick outsider. His lies helped swing the 2016 referendum. He lied in order to become PM in 2019. And, as the Parliamentary Committee of Privileges argued with unprecedented force and indignation, he lied repeatedly to parliament itself.

The lies he told are not ‘lies of state’. This is not Suez or Iraq. Johnson lied to conceal the fact that he and his staff routinely got pissed, shagged, and vomited in Downing Street at precisely the moment when he and his government were telling the population, in one sombre warning after another, that we should be doing the opposite of that; when bereaved and devastated people across the country could not even say goodbye to their loved ones on their deathbeds, or attend their funerals.

So all this is as fitting an outcome as anyone could imagine, and if Johnson is a victim, he is entirely the victim of his own moral squalor. He and his inner circle arrogated for themselves the rights that they instructed everybody else to forgo, and one of these rights was the right to party, in 2020, as if it was 1999, or a 1980s Bullingdon Club gathering. They did this, because their leader told them to do it or did nothing to stop it. And not because they were tragic heroes or great villains, but because, like their leader, they were shallow, selfish, and ultimately pitiful people who believed that they could act however they liked without any consequences.

Boris Johnson’s House of FunIf you don’t accept this - and amazingly there still people that don’t, read the Privileges Committee report. Bear in mind that the report only considers four of the mildest parties, not the more sordid Bullingdon/Hellfire Club grand bouffes, or the routine rulebreaking described by the ‘Downing Street whistleblower’ who told the Independent:

Inside No 10 was like an island of normality; nothing had changed since 2018, we were all operating as if there was no pandemic. It was utterly ridiculous. It was so widely accepted that we were all breaking the rules that we would receive operational notes from security to be aware that a camera crew were outside, and to remember to stay 2m apart when in front of the cameras. Huge efforts were made to make sure staff were playing up to the cameras – clearly these instructions had come from the top.

What fun they had, these gilded parasites in Johnson’s House of Fun, taking off their masks on trains and putting them back on when they arrived at a station. They deejayed, shagged, and vomited on the stairs. They karaoked Abba and passed out under their desks. They twirled awkwardly to the Pogues in their Christmas jumpers and joked about the rules they were breaking.

Bliss was it in that pandemic to be alive, but to be a Johnson staffer was very heaven. While these pampered buffoons cosplayed The Farce of the Red Death, most of the population had confined themselves to their homes, or took part in ‘socially distanced’ gatherings in their gardens for the best part of two years, in an exemplary demonstration of discipline and solidarity.

If British governments have sometimes been dishonest or economical with the truth, rarely, if ever, has government been so tawdry and degenerate. And all this is entirely due to the smirking charlatan, the bring your own booze man, the birthday party boy who loved his staff - or was it himself? - so much that he just had to raise their morale with a glass of water while he carried the nation’s burdens on his back. And all the time, he believed that he was ‘obeying the rules’ or ‘following the guidance.’

This is how Johnson repeatedly presented himself to his parliamentary peers, and last week a cross-party committee with a Tory majority refused to believe him. Not only did the committee conclude that Johnson lied to parliament repeatedly before the committee was even constituted, but it has also found him guilty of conspiring to discredit and undermine the committee itself, in a judgment that ought to be written on billboards across the country:

We have concluded above that in deliberately misleading the House Mr Johnson committed a serious contempt. The contempt was all the more serious because it was committed by the Prime Minister, the most senior member of the government. There is no precedent for a Prime Minister having been found to have deliberately misled the House. He misled the House on an issue of the greatest importance to the House and the public, and did so repeatedly. He declined our invitation to reconsider his assertions that what he said to the House was truthful. His defence to the allegation that he misled was an ex post facto justification and no more than an artifice. He misled the Committee the presentation of his evidence.

At this point, it’s tempting to echo the 1966 World Cup final commentary, ‘They think it’s all over, it is now’, as far as Johnson’s calamitous political journey is concerned.

Except that it isn’t. And not only because the Great Liar has refused to accept the committee’s verdict. Or because he was so convinced of his own righteousness that he resigned as an MP rather than attempt to defend himself. Or because he called the committee a ‘kangaroo court’ and conspired to discredit its members. Or even because he gave peerages to the same staffers who broke the rules and helped him cover up the fact that they were being broken.

It’s not even because Johnson now has a reputed £1 million a year contract with the Daily Mail. As martyrdoms go, this isn’t quite on the level of Edmund Campion, and ‘witch-hunts’ have tended to result in more deleterious outcomes.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

All this is to be expected, because this what Johnson is like, and has always been like. But as always the significance of Johnson goes far beyond the man himself. On Monday, 225 MPs abstained or stayed away from the parliamentary debate on whether to accept the Privileges Committee’s recommendations.

Many of them have been, and still are, all over television or social media like an angry rash, telling us to ‘move on’, or accusing Johnson’s detractors of focusing on trivia. Most of them have been amplifying Johnson’s ‘witch-hunt’ victim narrative. Some have cast aspersions on Bernard Jenkin, Sue Gray, Harriet Harman, and even - get this - the nurses who posted TikTok videos during the pandemic.

It takes a strong stomach to see nurses being placed on the same level as Johnson’s crazy gang. Or contemplate Brexiter politicians who once claimed to be standing up for the sovereignty of parliament, refusing to appear in parliament to take part in a debate because they knew they would lose it. You can remind them again and again that this is not a debate about ‘cake’, or even parties, but about the contempt of parliament that followed, but you might as well bang your head against a wall with the likes of Brendan Clarke-Smith, Lucy Allan, or Jacob Greased-Hogg.

On one hand this is pure disreputable cowardice - they take after their leader in this respect. No surprise that the chatbot-prefect Rishi Sunak was one of them; a damp J-cloth has more backbone. The same man who promised a new era of integrity in government refused to revisit Johnson’s sordid honours list, and then failed to turn up in the House of Commons to vote on a parliamentary report which turned on the central issue of… integrity in government.

Sunak may have done this because he is personally implicated in Johnson’s rulebreaking, and also because he is politically weak, and frightened of what Johnson’s trollish MPs might do to him. His attempts to placate Johnson’s pitchfork mob are unlikely to bring him any favours, because these are people who hate him anyway, and want their ‘top man’ back in the Big Job.

Many of Johnson’s absent supporters didn’t appear because Johnson told them not to - a tactical move motivated by Johnson’s political interests as well as their own cowardice. Unable to win the debate or even participate in it, the cultisits attempted to cast legitimacy on the vote - and ultimately on parliament itself - by leaving gaps on the benches.

If parliament was not going to do what they wanted, they would ‘boycott’ parliament. It makes a kind of sense. And it’s also a demonstration of Johnson’s continued toxic power. Because when push comes to shove, many of these MPs clearly prefer the sovereignty of Johnson to the sovereignty of parliament, and some of them undoubtedly prefer him to the Tory Party itself.

If - or should it be when? - the most successful political party in the western world receives the electoral decimation it deserves - some of these cultists may form the basis for a new political ‘national conservative’ formation, with Johnson and even Farage at its helm. Or they may seek to complete a Republican Party-style extremist takeover over the already-existing party that will take it even further to the right. Some of them, in their delirium, are already muttering darkly about ‘true conservatism’ as they contemplate a life in the political wilderness.

Whether any of these attempts succeed is another matter. The adulation of Johnson has always tended to exaggerate his supposedly charismatic political appeal. Beyond this moral ruin of a party, millions of people who didn’t see through Johnson’s act before, now understand exactly what he is.

When the time comes, in Uxbridge and beyond, we can only hope that they remember not just the parties that he held, but the party that put him there. Perhaps then, we can begin to take government seriously again. Perhaps we might look more closely at the clapped-out institutions that placed an amoral clown in the highest office in the land.

In the meantime, there is some satisfaction to be taken from the spectacle of the great greased pig for whom there were never any consequences for anything, no longer hanging from a zip-wire waving a union jack, but hoisted entirely by his own petard, where everyone outside the cult can see exactly what he is, and what he has always been.

June 14, 2023

Berlusconi Goes to Heaven

A week can be a long time in 21st century politics, and a trip to the Spanish and French Pyrenees meant that I haven’t been able to respond, among other things, to Silvio Berlusconi’s long-overdue departure from our world. Luckily for me, many other people have had the time. Giorgia Meloni has given Il Cavaliere a state funeral. Matteo Salvini wept, or says he did. Their grief is probably justified - they owe Berlusconi a lot.

Elsewhere Tony Blair has described his former holiday host as ‘a larger than life figure’ who was ‘shrewd, capable and true to his word.’ Vladimir Putin - no surprises here - called him a ‘dear friend’ and a ‘true patriot’

Many obituaries called Berlusconi ‘colourful’ and ‘not politically correct’ - the usual dreadful euphemisms bestowed on politicians whose essential crassness and vileness is eclipsed by a certain level of fame and legendary status. There’s no doubt Berlusconi achieved that, which is why so many people have taken the dictum of never speak ill of the dead to such ridiculous extremes in his case, because there is a lot of ill that can be said, and deserves to be said, about Silvio Berlusconi.

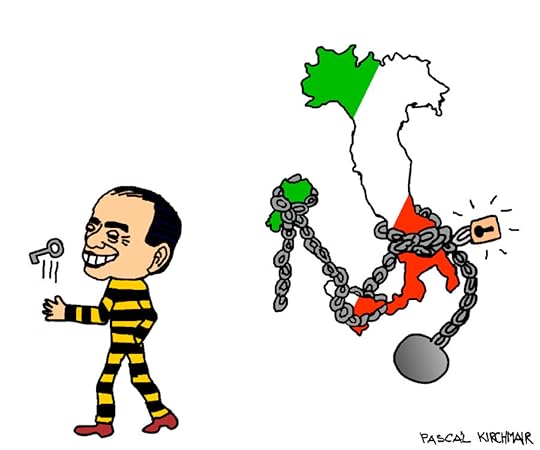

One of the recurring themes in our new era of rightwing populist demagoguery is that such and such a politician is ‘unfit for office’. What Berlusconi showed, long before anyone else, was that unfitness for office was no obstacle to achieving the highest office in the land, as long as you had enough money to pay for it and no moral or political scruples regarding what you did with it. In the early 90s, in the aftermath of the ‘tangentopoli’ - ‘Bribesville’ - scandal, and the collapse of Italy’s post-war political order, Berlusconi used his money and his media empire to sweep up the scrapings of Italy’s disgraced political class into a winning combination.

With the help of the racist Northern League and Mussolini’s fascist descendants, Berlusconi built coalition governments that changed the face of Italian politics, without, to paraphrase Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s famous observation about Sicily, really changing that much at all.

Though Berlusconi’s own political views leaned heavily towards the right, his involvement in politics was not dictated primarily by ideological reasons, but by the desire to save himself from criminal charges, which would have cost him a lot of money and might even have landed him in prison.

He did this not once, but on various occasions, with a shameless verve that appealed to millions of Italian voters, for whom his real or alleged crimes were always secondary to his entertainment value. Bribery, tax evasion, alleged Mafia association, involvement in prostitution, sex with minors, racism, sexism, homophobia - all this mattered as little to a certain kind of voter as it did to many world leaders, like Blair, who found Berlusconi ‘colourful’ and endlessly amusing, rather than repugnant.

Now he has finally gone, botoxed to the eyeballs, his face stretched into a kind of grotesque death mask long before rigor mortis set in. Those who believe in the afterlife better pray that Saint Peter is not as easily won over when Berlusconi shows up at the pearly gates with rictus grin and his cheque book out, and that he is finally subject to the justice that he never received on earth.

For those of us who don’t believe in such things however, it’s clear that this was a politician who got away with everything he wanted to get away with, and with bells on. He lived an entirely corrupt life, dedicated entirely to his own gratification, and neither Italy’s political or judicial institutions were ever able to lay a finger on him.

It took death to do what the Italian electorate should have done decades before, but could not be bothered to do, because too many voters enjoyed the spectacle of shamelessness that he paraded before them, and perhaps because too many of them wanted to live their lives the way he did.

The PioneerBerlusconi has been described, ad infinitum, as a politician who paved the way for Trump, Bolsonaro, and the other monsters who have wrought havoc on our contemporary ‘post-truth’ democratic dystopias. It’s interesting - however coincidental - that Berlusconi died in the same week when a kind of justice came closer to two of the politicians who have most closely adhered to the charlatan/demagogue prototype that he introduced into the post-Cold War world.

First, there was Boris Johnson’s ridiculous resignation as an MP, in response to the ‘kangaroo court’, as he described the parliamentary Privileges Committee, that appears posed to find him guilty of misleading parliament. Johnson did this to avoid a suspension that at most, might have triggered a by-election in his constituency, and at the very least would have constituted a humiliating precedent in British politics.

Cowardly and bombastic to the last, Johnson is ducking, diving, lying and conspiring to avoid this ignominious outcome. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, Donald Trump appeared in court, charged with an astonishing 37 federal crimes, relating to his ludicrous possession of unclassified documents.

On the face of it then, it has been a bad week for bastards: One dead, one facing humiliation, and another facing jailtime.

But any such triumphalism should be tempered. It should not have taken the Grim Reaper to wipe the frozen grin off Berlusconi’s face. Johnson was not beaten politically; he was beaten by himself, unravelled by the moral incontinence and pampered sense of entitlement that should have been spotted long before he got into Downing Street. Trump is still a contender for the US presidency, and the only reason he has been charged is because he was dim and arrogant enough to conceal classified documents and boast about it in front of visitors to his Mar-a-Lago house of gilded horrors.

Naturally, none of this is their fault. Where Berlusconi claimed that he was being persecuted by ‘communist’ judges, both Johnson and Trump are trying to portray themselves as victims of sinister anti-democratic conspiracies and witch-hunts. Both of them are lying, as they have always done, and it remains to be seen whether they get away with it, as Berlusconi did.

Like Berlusconi, both of them have devoted followers who are lying with them, or willing to be lied to, or simply want to continue to be amused by the clown-politicians in whom they see nothing more than entertainment. In the UK, Johnson’s Tory supporters are now trying to destroy their own government and party in order to save the tarnished oaf on whom they were vicious or stupid enough to project their depraved hopes.

In the US, Republican politicians are now openly threatening armed insurrection to save their criminal former president from justice and ensure that he becomes president once again.

No one should be complacent enough to write off these possibilities. We can but hope that a disgraced Johnson never returns to public life, just as we can hope that Trump goes to jail. But it should not have taken their personal failings to bring us to this point. The failings were always obvious. Too many people refused to look, or could not be bothered.

Both men, like Berlusconi, are symptomatic of a deep democratic malaise and of wider collective moral failings that are not limited to them, and which will continue to ensure that other politicians like them - or even worse - take their place in the coming years. Vox in the Spanish government, an AfD coalition in Germany, the return of Bolsonaro - these are only some of the possibilities lurking round the corner.

There is no easy or obvious antidote to this toxicity, but it must involve a genuine democratic renewal, in which morality returns to politics and the notion of the common good becomes the central concern of democratic politics and good government.

Johnson and Trump, like Berlusconi, invited voters to be the worst that they could be, or at least to accept the lowest common denominator as a viable political choice. We need electorates that will refuse that invitation. We need voters who will ask their politicians to be the best that they can be; who should expect - and demand - governments that try to change society for the better instead of merely amusing us or humiliating our real and imaginary enemies.

We need to learn - relearn - to value honesty and integrity, vision and commitment more than entertainment, so liars and crooks are not forgiven just because they amuse us for a few minutes, or allowed to die without ever having been held accountable for their crimes.

In other words, we need to be better than we have been, in order to get the politicians we deserve. And if we can’t do that, then the likes of Berlusconi, Johnson, and Trump will continue to win, and we will all continue to lose.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

June 1, 2023

Henry: Portrait of an Imperial Killer

I can’t say I’ve ever been a fan of Henry Kissinger, but it’s been clear to me, throughout his seemingly endless career, that he has a lot of admirers. Many of them were around this week to congratulate him on his 100th birthday. The Wall Street Journal hailed the ‘great strategist’ whose ‘appetite for the world he’s spent a lifetime setting to rights is still zestful.’ In the Mail, Dominic Sandbrook described Kissinger as ‘an extraordinary man: a shy, stammering refugee who became one of the most powerful men in the world, dated some of Hollywood’s most beautiful women and seemed to hold the fate of the nations in the palm of his hand.’

Unlike the WSJ, Sandbrook did at least recognise that Kissinger was ‘intensely controversial’, though he also question why the man who once ‘beguiled Brezhnev and Mao’ has been singled out for ‘ferocious criticism’ compared with other US Secretaries of State.

It’s certainly true that Kissinger has tended to attract more negative attention than some of the other men and women who have occupied the same post, but the ferocity of the criticism directed against him has done nothing to harm his reputation. Whatever bad things Kissinger has done, there are always more people willing to forget about them than there are to hold him to account. Few other American diplomats have been so widely-revered, and so constantly present. Of all the ‘national security managers’ who oversaw US foreign policy during the Cold War, Kissinger has acquired a unique aura of statesmanlike gravitas. He is the diplomat-celebrity, the realpolitik man, the magus of the global ‘chessboard’, whose owlish wisdom always seems relevant to every world crisis.

These qualities tend to overshadow the often bloody and sinister events that have punctuated his long career.

The secret bombing of Cambodia; Pakistan’s brutal devastation of Bangladesh; the Indonesian invasion of East Timor; Vietnam; the Chilean coup; the Angolan civil war; El Salvador and Central America in the 1980s - inevitably Kissinger’s name crops up when there are dirty deeds to be done, providing support for regimes carrying out the most atrocious acts and dismissing those who criticise them, as he once did with Pakistan, when he sneered at the people who ‘bleed’ for the ‘dying Bengalis.’

Maybe it’s not polite, when a great man reaches his hundredth year, to dig too deeply into such unpleasantness, but this landmark provides as good an opportunity as any to revisit the profound cynicism that underpinned his decisions.

Anyone who doubts this, should read some of the cables and documents regarding Kissinger’s backroom support for the Argentine dictatorship, such as the chilling account of Kissinger’s meeting in Chile on June 6 1976, with the Argentine Foreign Minister, Vice-Admiral Cesar Guzzetti, that was released many decades later.

Kissinger was then Foreign Secretary in Gerald Ford’s caretaker government, and the meeting took place less than three months since the junta had seized power in Argentina. After some cheery banter about football and American politics, Guzzetti cuts to the chase, and informs Kissinger that

our main problem in Argentina is terrorism…There are two main aspects to the solution. The first is to ensure the internal security of the country; the second is to solve the most urgent economic problems over the coming 6 to 12 months. Argentina needs United States understanding and support to overcome problems in these areas.

To which the Great Man replies:

We have followed events in Argentina closely. We wish the new government well. We wish it will succeed. We will do what we can to help it succeed. We are aware you are in a difficult period. It is a curious time, when political, criminal, and terrorist activities tend to merge without any clear separation. We understand you must establish authority.

At that time, the Argentine military government was ‘establishing authority’ through a state-sponsored regime of murder, torture, and forced disappearance, in which political, criminal, and (state) terrorist activities did indeed ‘tend to merge’. Some of this was known abroad, as Guzzetti indignantly points out:

the foreign press creates many problems for us, interpreting events in a very peculiar manner…It even seems as though there is an orchestrated international campaign against us.

Yes, why can’t we throw people from helicopters without people saying nasty things about us? Once again Henry is sanguine and sympathetic:

I realize you have no choice but to restore governmental authority. But it is also clear that the absence of normal procedures will be used against you.

Note that Kissinger’s concern - and the concern of his government - with this ‘absence’ is entirely political. If there is any outrage and disgust at the ‘procedures’ introduced by a savage and lawless military dictatorship, it is not present in this conversation.

The Great ChessmasterIn Kissinger’s diplomatic world, there are times for shaking hands with Mao and there are times when people have to die, although this can never be openly acknowledged by a powerful democracy that couches its war on totalitarianism and communist tyranny as a moral project. As the arch-practitioner of ‘realpolitik’, in the sense of politics ‘based on practical objectives rather than ideals’, Kissinger understood this very well.

Publicly, the United States exercised ‘moral leadership’ against an irredeemably evil enemy. Privately, Kissinger knew better, and he wasn’t the only one. This becomes clear when the conversation turns to the subject of Chilean refugees in Argentina, many of whom, Guzzetti insists, ‘provide clandestine support for terrorism’. Guzzetti offers no evidence for this, and none is needed, given Kissinger’s personal contribution to the overthrow of Allende. Instead the Vice-Admiral tells Kissinger that governments in all the southern cone countries are integrating their efforts to ‘create disincentives to potential terrorist activities’, whereupon the following exchange occurs:

KISSINGER: Let me say, as a friend, that I have noticed that military governments are not always the most effective in dealing with these problems.

GUZZETTI: Of course.

KISSINGER: So, after a while, many people who don’t understand the situation begin to oppose the military and the problem is compounded…If there are things that have to be done, you should do them quickly. But you must get back quickly to normal procedures.

This is one of those conversations, familiar to masters of the global ‘chessboard’ and also to certain gangsters, in which its participants know exactly what they are referring to, but are too decorous to spell it out directly. There are merely ‘things that have to be done’, and what Guzzetti can take from this exchange is that the United States will not oppose what his government is doing, either nationally or internationally, as long as Argentina gets it done quickly, after which ‘normal procedures’ must be resumed.

Even so, the Vice-Admiral still needs further reassurance, which the chessmaster is pleased to give him:

GUZZETTI: The terrorists work hard to appear as victims in the light of world opinion even though they are the real aggressors.

KISSINGER: We want you to succeed. We do not want to harass you. I will do what I can. Of course, you understand that means I will be harassed. But I have discovered that after the personal abuse reaches a certain level you become invulnerable.

Kissinger might have said, that when you reach a certain level of statesman-celebrity status in a global superpower operating under a veneer of plausible deniability, you become invulnerable, because even then, he was.

This is why he can be found in a declassified document, giving one of the worst regimes of the 20th century - and its partners - a carte blanche to do the ‘things that have to be done’. It’s also why the Argentine dictator Jorge Videla invited Kissinger to the World Cup in 1978. Kissinger was a private citizen then, but his invitation was a pointed rejection of the Carter administration’s human rights-focussed foreign policy, which made US economic and military assistance conditional on not using ‘thumbscrews’ as Carter’s formidable Assistant Secretary of State Patricia Derian, once put it.

In 1977, the former civil rights activist Derian visited Buenos Aires, where she spoke with Argentine human rights official, journalists, and the US Embassy Country Team, as a result of which she concluded:

The [Argentine] government method is to pick people up and take them to military installations. There the detainees are tortured with water, electricity and psychological disintegration methods. Those thought to be salvageable are sent to regular jails and prisons where the psychological process is continued on a more subtle level. Those found to be incorrigible are murdered and dumped on garbage heaps or street corners, but more often are given arms with live ammunition, grenades, bombs and put into automobiles and sent out of the compound to be killed on the road in what is then reported publicly to be a shootout or response to an attack on some military installation.

These were those ‘things that have to be done’ in Kissingerspeak. During her visit, Derian also met the sinister Admiral Massera, to whom she showed a floor plan of the building they were meeting in and declared: ‘You and I both know that as we speak, people are being tortured in the next floors.’

The regime was not used to being spoken to like this, and it didn’t like it, especially when Derian explained to Congress why the Department of State decided to withhold a credit of more than $200 million for a dam project in Argentina.

The reason for our advice was the continuing violation of basic human rights by Argentina. The systematic use of torture, summary execution of political dissidents, the disappearance and the imprisonment of thousands of individuals without charge, including mothers, churchmen, nuns, labor leaders, journalists, professors and members of human rights organizations, and the failure of the government of Argentina to fulfill its commitment to allow [a] visit by the Inter American Commission on human rights.

Kissinger took a different view during his World Cup visit. An avid soccer fan, he was feted by Videla and his cohorts, and he returned the compliment by applauding ‘Argentina’s efforts in combatting terrorism’ whenever he could. An American diplomatic cable at the time described such pronouncements as ‘the music the Argentine government was longing to hear, and it is no accident that his statements were played back to us by the Southern Cone countries during the O.A.S General Assembly.

The Carter human rights policy was never entirely effective or coherent, and it turned out to be a temporary lull, as the Reagan administration subsequently reversed it. But Carter himself was sincere, and Derian tried hard to put these new principles into practice. In 2016 she died at the age of 86.

That same year, Jon Lee Anderson asked whether Kissinger had a conscience. Anderson described what happened when the journalist Stephen Talbot interviewed Kissinger, shortly after the release of Errol Morris’s 2003 documentary about Robert McNamara - another of the Cold War ‘national security managers’, who at least expressed some regret at the consequences of the policies he had been involved in.

According to Talbot:

I told him I had just interviewed Robert McNamara in Washington. That got his attention. He stopped badgering me, and then he did an extraordinary thing. He began to cry. But no, not real tears. Before my eyes, Henry Kissinger was acting. ‘Boohoo, boohoo,’ Kissinger said, pretending to cry and rub his eyes. ‘He’s still beating his breast, right? Still feeling guilty.’ He spoke in a mocking, singsong voice and patted his heart for emphasis.

That’s the great chessmaster for you. In an obituary for Patricia Derian, the New York Times wrote that ‘thousands of lives may have been spared because of her work.’ That is something no one will ever be able to say of the man who turned 100 last week, of whom it would be more accurate to say that thousands of lives may have been lost because of his work.

Too many people forget that. Or they simply don’t care. And however long Henry Kissinger lives for, one thing is certain: he will go to his grave as untroubled by any of the ‘things that have to be done’ as he was when he sat down to chat, in 1976, with the foreign minister of one of the worst regimes on earth.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 25, 2023

Twilight of the Clods

Karma is an overrated force in politics and in life. It rarely comes when you want it to, and mostly it doesn’t come at all. Its absence has been particularly notable in these depraved political times, when lies are greeted with tickertape parades; where the loudest, the most corrupt, the most malignant, the most useless and incompetent, and the most dishonest people even the most dystopian imagination can conjure up, not only get away with it, but actually thrive and prosper.

But sometimes, retribution of a sort does come, slipping in by the most circuitous and unlikely routes, and such appears to be the case with the moral vacuum known as Alexander de Pfeffel Johnson. For those who believe that history does occasionally have plotlines, it’s extremely satisfying, however implausible, to see how Johnson took the unprecedented step of using lawyers to fend off a parliamentary enquiry, only to find that these same lawyers have handed over documents implicating him in further Partygate breaches to the Cabinet Office, which then handed them to the police.

We can ask why these breaches were not investigated by the police or Sue Gray in the first place, but really we should be giving Karma a big hand, because this was neatly done, and it couldn’t have happened to a more deserving guy. If this was a tv series - lets call it Bastard - you would definitely want another season. It could be the stuff of Greek tragedy, if the hero was not a morally incontinent Hooray Henry, who partied while his people died, and if the wounds that he inflicted on himself consisted of something more than vomit on the walls of Downing Street and probably Chequers as well.

The genuine tragic hero has a tragic flaw that brings him down, but Johnson is nothing but flaw, with all the tragic grandeur of Benny Hill performing drunk in It’s a Knockout. This is a king who should never have sat on his metaphorical throne, a man who has never served anyone but himself, whose entire career has been based on his ability to lie with a smirk, with the gormless applause of too many people who should have known better, and too many who never did, and stuck with him anyway, because they believed he could further their interests.

Now, once again, Johnson has shown that you could take the boy out the Bullingdon Club, but you can’t take Bullingdon out of the boy, and he is floundering in the mess he made entirely by himself, and all because, to paraphrase the Beastie Boys, he lied for his right to party in the midst of a lethal pandemic even as he told everyone else to do the opposite.

It that isn’t a series to get the popcorn out for, I don’t know what is. That’s not how he and his pals see it of course. No tragic flaw for them, only The Parallax View for morons, in which every reversal, ever blow, every setback that their hero suffers, is actually the fault of the shadowy conspirators behind-the-scenes. They might be the ‘lefty media’ as the ludicrous troll Dan Wootton put it in the Mail today, dipping his greasy fingers even deeper into the dreck than usual. Or they might be ‘the Blob’ - the sinister cabal of liberal woke civil servants that tried to ‘stop Brexit’ and now wants to take revenge on the man who got Brexit done, even when he didn’t.

They might also be the Sunakites - the same serpent-tongued smoothies who stabbed our hero in the back - et tu Rishi! - and now want to finish him off.

Whoever they are, they are evil. Evil I tell you. Cowards and knaves, conspiring against a great man more sinned against than sinning, the man who gave us Brexit and the vaccines and saved us from Marxist tyranny and saved Ukraine and blah blah blah - the emperor of the land where pigs fly with a cheque from Sam Blyth in their trotters.

This is playground-level discourse, of the kind that we have become tediously accustomed to over the last few years, no matter how deeply we might plunge our fingers into our ears. It is pathetically dishonest and pathetically demeaning, not only in its complete indifference to truth, but in its arrogant assumption that its listeners are stupid enough to believe it.

Some will, but the evidence suggests that many more won’t. Because if enough people had believed these narratives when Johnson was in power, then he wouldn’t have fallen from power in the first place. In the real world, which still counts for something - just - he was removed by his own party, not because his party had suddenly regained the decency and morality that they lost when they brought the scheming oaf to power, but because the public revulsion at Johnson’s rule-breaking and lying was so visceral and widespread that it had placed their own careers in jeopardy.

The Coalition of the DamnedThat hasn’t changed, and it’s now very likely that further revelations may make it worse. The ‘seething’ backbenchers now joining the Johnson rent-a-mob can seethe till smoke comes out of their backsides. They can weaken Sunak, but it’s unlikely that they can destroy him, while Sunak lacks either the moral fibre or the political will to see off the Johnsonites, the Trussites and the Bravermanites, or the once-feared Urg.

In effect, the Tory coalition that Johnson assembled has bet everything it had at the Brexit casino and come out of it with nothing but some air tickets flying refugees of their choice to Rwanda. Now that coalition is fractured, and it’s difficult to see how it can be put back together by anyone, let alone by Johnson.

Beyond Brexit, they had only Liz Truss’s tax cuts utopia, which died at birth. And a country without immigrants, which now turns out to be a country where immigration has increased, because - who’d have thought? - it turns out that immigrants are needed.

So on one level the current turmoil is good news to all of us who see this party as a blight on the nation, as its factions turn against each other, and yet cannot destroy each other, and grope around in the dark for a leader or a big idea that can bring them back from the abyss.

They can, as I suggested last week, lurch even further to the right, and lose the few moderate Tories who still remain in the party in the process. Or they can lean back towards the centre and lose the lunatics. They can pursue the Johnson-as-victim fantasy, which is neither, and will only keep Johnson in the news, thereby increasing the public disgust towards him and everyone around him, while bringing more pressure to bear on their crumbling seats.

These are not games that winners play, and many MPs clearly realise that the game is up, which is why 10 percent of them are standing down, rather than face their night of shame. And many of those who aren’t standing down will almost certainly be forced out, as a shattered, demoralised, and angry country wakes up to the damage that has been done to it and finally takes revenge on the parasites and grifters responsible for it.

In other words, the most successful political party in the world is locked into a death spiral, and clinging to Johnson is only likely to speed it up. As a well-known pseudo-classicist, the Great Bloviator will no doubt be familiar with Marcus Aurelius’s maxim: ‘Rotting meat in a bag. Look at it clearly. If you can.’

Johnson is the meat. The Tory Party is the bag. And it is very doubtful that it can look clearly at what is inside it. That would mean looking at itself.

But many other people will look. Or smell the stench of decay, whether it comes from Chequers or Teeside.

They know that, whatever comes next, this is a party that deserves defeat and disgrace more than any party has ever done. They know, as Oliver Cromwell once said of the Long Parliament,that the Tory Party is ‘a factious crew, and enemies to all good government; ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of pottage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money.’

This is as true now as it was then. So let Johnson and his supporters cry conspiracy as more sleaze leaks out. Eat your popcorn, but guard your vote, until the opportunity finally comes to confine this dreadful rabble to the oblivion they deserve.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 19, 2023

A Plague of NatCons

Many years ago I stayed at a hotel in Varanasi overlooking the River Ganges. Most days, if you sat out on the terrace, you could see the corpses of animals floating down the river, and some people said that sometimes you could see human too, though I never did. Watching the National Conservatism conference unfolding in London this week felt a little like that.

For those that don’t know, these conferences are a rolling event, put on by the Edmund Burke Foundation over the last few years, which aim to gather speakers who many people outside these events would consider to be on the radical right/far right fringe. Boris Johnson’s government once did anyway, back in 2020, when it criticised MP Daniel Kawczynski for attending the National Conservatism conference in Rome, along with the likes of Victor Orban, Matteo Salvini and Georgia Meloni.

Times change, and so do failing governments. And this week’s conference was attended by Conservative Party backbenchers and cabinet ministers, with the tacit approval of a supine premier who either didn’t know or didn’t care.

I didn’t follow the conference in granular detail, because life really is too short, but it was impossible to avoid the stream of half-baked ideas, dank straw men, shibboleths, half-truths and semi-truths and general hysterical craziness that floated through my Twitter feed on a daily basis.

First up was the Home Secretary, clearly on manoeuvres and looking to outflank the hapless Rishi Sunak from the right, with a typically infantile speech declaring that ‘white people should not feel guilty’ about their history and inviting her audience to ‘venerate our past’ instead. Then there was Miriam Cates warning that the country was not having enough babies.

And Douglas Murray delivering a talk in the Natural History Museum under the skeleton of a whale, in which he said that national pride should not become obsolete just because Germany ‘mucked up’ nationalism in the 20th century.

The very least that can be said about this is that is an extremely questionable notion, but not nearly as much as David Starkey’s suggestion the Left feels ‘jealousy’ towards Jews, and wants ‘to replace the Holocaust with slavery in order to wield its legacy as a weapon against Western culture.’

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Wrap your head around that one if you can. And while you’re at it take a look at Matt Goodwin declaring that ‘The Left pushed for hyper-globalisation, which prioritises the interests of Big Business & urban graduates, over the interests of the national community.’

Faced with such idiocy, you can’t wondering what ‘the Left’ could have done if it had had even a smidgeon of the power on a national and global scale that these grifters say it has, but these are not people to allow reality to intrude on their ‘NatContalk’. After all, as the Telegraph’s Tim Stanley astutely observed ‘If we’re going to go to war on anything which does put the word “national” in its name, we’re also going to have to crackdown fast on the National Trust, the NSPCC and the NHS.’

Genius.

Elsewhere, you could find David Frost or ‘Lord Frost’ as he has become inexplicably known, describing ‘the spirit of Brexit’ as ‘ the spirit of nationhood’. It’s probably a sign of the times that Frosty the NoMark seems to think he is a man for the times. But no more absurd than Lee Anderson delivering a keynote address in which he told his audience to be ‘incredibly proud to live in this great country, and I’m incredibly proud to have been born here.’

Yeah, kudos to Lee’s parents for having sex and giving birth to him. No wonder he’s proud. On and on it went, like a carnival of the damned, an opening of the British hellmouth, a walpurgisnacht in which all the sweepings and shavings of the last three dire decades came together in one place. There were blue labourites, pseudo-leftists, hard liberals and freezepeachers dancing naked and smearing themselves with hard-right woad while the likes of Melanie Phillips scattered them with psycho-dust.

There was Darren Grimes, the perpetual minnow in his charity shop shark suit, swimming desperately with the big guys. There was David ‘people from somewhere’ Goodhart, Frank Furedi and Nina Power. There was Toby Young insisting that the ‘priests’ of the ‘woke morality’ are totalitarian because they ‘refuse to assume robes of office.’ And a priest called Benedict Kiely comparing a ‘Christian nation without its foundations’ to ‘an IKEA pre-made building, ready to collapse.’

Inevitably there was Katherine Birbalsingh, ‘Britain’s strictest headmistress’ delivering a remarkably shrill and more-than-a-little unhinged speech in which she called on her audience to show their love of their country by taking their children out of ‘woke schools’ or tweeting under their own name, even though she doesn’t do that herself.

Birbalsingh even invoked Russell Crowe from Gladiator - a great film which didn’t deserve this - in calling on her audience to ‘hold the line’ against the massed forces of wokedom.

I don’t know what was worse, the conceptual incoherence or the megalomaniac self-importance, but Miss Snuffy wasn’t the only one to exude these qualities.

The Paranoid StyleIn his classic essay on rightwing US politics, Richard Hofstadter referred to ‘the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy’ that defined what he called the ‘paranoid style’ of American politics. And on the evidence of last week that ‘style’ is well and truly over here, and taking our men as well as our women.

As Hofstadter put it, the proponent of the paranoid style sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms—he traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values. He is always manning the barricades of civilization. He constantly lives at a turning point.’

These words could have been included in the ‘about’ section on the London conference, in which the apocalypse was always just around the corner and may even have started. Wokedom, ‘cultural Marxism’, the left, godless secularism, globalists’ cultural relativists, Black Lives Matter, trans people - all these barbarians were beating the gates of ‘Western civilization.’

What to do about it? In a wild and yet quite revealing speech, Danny Kruger, the backbench MP and former speechwriter for David Cameron, had a go. Kruger gave a speech on psilocybin in parliament yesterday, and he must have been taking some of it earlier in the week. He begins his speech with a discussion of Brexit, and the drug must have just been coming on, because it’s the usual whining victimhood and self-deception that we have come to expect from Brexiters in recent years, and which has grown louder as the Brexit water gurgles noisily down the plughole.

According to Kruger, the UK set out in 2016 to ‘renew the basis of our politics’, only to be thwarted by the EU, which refused to ‘make Brexit work for both sides.’ Instead ‘we were pushed about like a child in the playground encircled by bullies, unable to break out’, until Boris Johnson finally had the courage to stand up to ‘Parliament, the judiciary, and the civil service’ and forced the EU to ‘take notice’ of us. As a result, ‘we broke free. We crashed through the ring of bullies and made it to the people and forced an election.’

So all good then? Not really, because the promises to ‘the people’ have still not been met. After a not entirely unreasonable account of the UK’s longterm economic failures, and his own party’s role in them, the drugs must have kicked in suddenly, because Kruger then veers off into uncharted Tory territory as he turns his attention to ‘the weird medley of transgressive ideas that is now threatening the basis of civilisation in the West.’

What are these ideas? You guessed it. Or did you?

We have overseen the radicalisation of a generation. In the name of a new ideology - a mix of Marxism and narcissism and paganism, self-worship and nature-worship all wrapped up in revolution.

Paganism, you say? And lock up your daughters, because these Marxist narcissistic pagans are trying to ‘build their new Jerusalem - their pagan city on a hill.’ And in order to do that

first the old one must be destroyed. Everything must be undermined. Dismantled. Swept away. Everything must conform at last to the imagining of John Lennon: No countries. No families. No religions (except this one). Nothing to live or die for. No history, just a bland progressive present. And over all of it -benign, omniscient, omnipotent - the progressive state.

I’m not sure if this exactly what John Lennon was singing about. Some readers may have wondered where this ‘progressive state’ has been the last thirteen years, but Kruger insists that this ‘dystopian fantasy’ is a real possibility, and he urges those who doubt it to ‘remember Covid’.

Was Covid part of the pagan narcissist conspiracy then. Kruger doesn’t say, but he knows what is necessary to stop it.

Imagine there’s no woke, it’s easy if you trySo what is the solution to these horrors? Well, for a start, there is ‘the normative family – held together by marriage, by mother and father sticking together for the sake of the children and the sake of their own parents and for the sake of themselves – this is the only possible basis for a safe and successful society. Marriage is not all about you. It’s not just a private arrangement. It’s a public act, by which you undertake to live for someone else, and for wider society; and wider society should recognise and reward this undertaking.

Kruger might want to have a word in his hero Boris Johnson’s ear about these commitments and obligations, but he wasn’t the only speaker to evoke the ‘normative family’ as a pillar of the ‘national conservative’ order. This is one of the key ideas in the national conservatism project. As its website’s ‘statement of principles’ makes clear:

The traditional family, built around a lifelong bond between a man and a woman, and on a lifelong bond between parents and children, is the foundation of all other achievements of our civilization. The disintegration of the family, including a marked decline in marriage and childbirth, gravely threatens the wellbeing and sustainability of democratic nations.

I see. But the traditional family cannot thrive on its own, because

No nation can long endure without humility and gratitude before God and fear of his judgment that are found in authentic religious tradition. For millennia, the Bible has been our surest guide, nourishing a fitting orientation toward God, to the political traditions of the nation, to public morals, to the defense of the weak, and to the recognition of things rightly regarded as sacred. The Bible should be read as the first among the sources of a shared Western civilization in schools and universities, and as the rightful inheritance of believers and non-believers alike.

Blimey. And what kind of government should we have? Well, a small state, in general, but not too small:

We recommend the federalist principle, which prescribes a delegation of power to the respective states or subdivisions of the nation so as to allow greater variation, experimentation, and freedom. However, in those states or subdivisions in which law and justice have been manifestly corrupted, or in which lawlessness, immorality, and dissolution reign, national government must intervene energetically to restore order.

However ‘energetically’ the national government may be forced to act in such circumstances, the statement of principles insists that:

necessary change must take place through the law. This is how we preserve our national traditions and our nation itself. Rioting, looting, and other unacceptable public disorder should be swiftly put to an end.

If you think that all this sounds just a little bit authoritarian and even fascistic, you would not be wrong, though its more immediate goal is probably closer to Viktor Orban’s Hungary, Russia or Erdogan’s Turkey than Nazi Germany or fascist Italy. The signatories consist of a plethora of rightwing and paleoconservative luminaries and up-and-coming stars, including Christopher DeMuth from the Hudson Institute, the Spectator’s Amber Athey, Victor Davis Hansson, Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk, and Peter Thiel.

Its ideology reaches into that space vacated by ‘traditional’ conservatism, which has been taken over by the likes of Donald Trump, Josh Hawley, Marjorie Taylor Greene… and Suella Braverman. On one level we should be grateful for the fact that it has been so fervently embraced by so many individuals who have floated in and out of these politics for so many years without overtly declaring them.

When people tell you who they are, believe them the first time. Too many people didn’t, and now we know, or should know, if we didn’t before, who they are and the political company they want to keep.

The London conference is almost certainly a sign of things to come within a Conservative Party shattered by its embrace of the ruinous Brexit project. This week, no less than Nigel Farage admitted that ‘Brexit has failed.’

Naturally this was not his fault, nor will it ever be his fault, or the fault of the project itself. But none of the politicians responsible for that failure will ever acknowledge it without bringing about their own political ruin, so it’s entirely natural that so many Brexiters should be seeking to avoid scrutiny of that failure though culture wars and the invocation of the ‘national community.’

The problem is that the Conservative Party had already shifted to the radical right as a result of Brexit, and driven out out moderates or more traditional One Nationers from the party during the Johnson ascendancy. Now, the presence of so many Tory luminaries at this conference suggest that they are prepared to go even further rightwards, to that dark place where Christofascism, Trumpism, ‘wars on woke’ all overlap with the prospect of a ‘civilisational’ war at home and a war with China.

It’s tempting to assume that they won’t succeed, without splitting the party, which would not be a bad thing for the rest of us. But no one, after the last seven years, should take that outcome for granted, let alone assume that there is something in the British national character that is somehow impervious to the national conservative siren song.

The National Conservatism website includes a speech on ‘God, homeland, and family’ from Georgia Meloni at the 2020 National Con Conference in Rome. Meloni is now the Italian Prime Minister, and there clearly those, like Braverman and Frost, who dream of repeating that journey over here, at least further down the line.

This is not likely in the short-term, but in the longer term this movement is in it to win it. If - and it still is an if, unfortunately - Labour wins the next election and fails after one or two terms, and the Tory Party fragments, we can expect to see and hear a lot more where this came from. And the challenge that British society, and so many other societies face, is to come up with a different set of principles and values around which to organize, and a different story of what the country might be, to counter the fearful exhibits in the National Conservative shop of horrors.

And only if we can do this, can we hope that the ideas we heard over the last week will become one ideological skeletons, exhibits in a historical museum that are as remote from the present as the whale bones and dinosaurs that hovered over Douglas Murray and his audience.

May 8, 2023

Kinging in the Rain

The problem with my people, Ernest Bevin is supposed to have said on occasion, is the poverty of their desire. It was a line that Bevin borrowed from the Labour MP John Burns, who once observed that ‘the curse of the working class is the fewness of their wants, the poverty of their desires.’ Whether that is really true of the English working classes, Bevin’s observation has always seemed to me an alarmingly accurate description of the English in general.

Whatever EP Thompson and others may have said about the incipient radicalism of the ‘freeborn Englishmen’, there are too many English people who are willing to put up with a great deal, and too willing to allow those who are richer and more powerful than they are to get away with a great deal.

When, for example, Margaret Thatcher allowed one industry after another to go to the wall, and stripped away the supports that held entire communities together, there were people who resisted that transformation, but there were millions more who shrugged their shoulders and accepted it, because Tory governments and the newspapers that supported them convinced them that there was no alternative.

When David Cameron and George Osborne began to bleed communities dry across the country in the name of austerity and good economic housekeeping at a time of crisis that these communities had not caused, millions of people accepted all the social cruelty and callousness that went with it.

When foodbanks began to pop all over one of the richest countries on earth, millions accepted this as if it were all entirely natural and even laudable. The passivity was such that when Tory MPs who voted to cut benefits dropped in at their local foodbank for the occasional gurning photo op, only a few complained, because wasn’t it nice to volunteer?

Given this history, it’s not at all surprising that England has largely submitted with the same passivity in the face of the worst cost-of-living crisis since records began, people dying while waiting in ambulances, or hundreds going blind because they can’t get a routine ophthalmologist’s appointment. Yes, I know there have been strikes, but when giant energy companies are raking in enormous profits while your energy bills double or treble, you can’t help thinking that something more concerted is required, and that the government responsible deserves a lot more hostility than it is getting.

Of course we moan, the way we moan about the weather, but few of us seem to question the political and economic choices that have allowed such things to happen. A German magazine might describe the UK as a declining nation on life support, but too many of us prefer to put our fingers in our ears, or get angry at migrants, leftists, ‘woke’ people, or whatever enemy du jour is presented to us. When we do rebel, it will be a rightwing reactionary rebellion like Brexit that leads nowhere; and when we discover that the eggs that were broken in the course of that rebellion haven’t produced an omelette, we shrug our shoulders about that too, and never question the people who promised us it would all be different.

It would be understatement to say that this is all very frustrating for those of who believe that these things need not have happened, and that we have the potential to become a better country than we actually are. And there is no more glaring evidence of the poverty of English desire than our enduring infatuation with the Royal Family.

Millions of freeborn Englishmen and women do not question even for a single millisecond the vast power, wealth and inherited aristocratic privilege that royalty embodies. On the contrary, many of them positively fawn over it, or try to bathe in its reflected light. Whether they really believe that kings and queen were appointed by God or just ended up there by good luck, they are willing to maintain the Royal Family in exactly the same place it has always been.

Yes, there has been the occasional tremor of discontent, for example during the ‘floral revolution’ that followed the death of Princess Diana - a ‘revolution’ that had more or less disappeared like a candle in the wind even before the flowers had wilted.

How many eulogies to England and Englishness did we hear back then? How many pundits oohed and aahed at the softer nation we’d become, as the famously stiff upper-lipped English finally learned to cry over the ‘People’s Princess’.

Never mind that the same weeping public had pored over Diana for so many years, fuelling an amoral and ruthless pursuit of saleable photogenic material that eventually drove her to her death; none of this dented the new media consensus that the outpouring of performative grief represented the birth-pangs of a new England in which the English had lost their habit of deference, and that the Royal Family had to watch itself and ‘modernize’ if it wanted to survive.

If the House of Windsor was genuinely worried about this transformation at the time, it needn’t have. Because deference did not disappear, and millions of us, it seems, would rather be proud to be subjects of monarchs than citizens on an equal footing with each other.

Some say that the Royal Family is the only thing protecting us from dictatorship or President Boris Johnson, as if these were the only alternatives available. Others insist that we need the Royal Family to know what England is, and what Britain, as if there were not other way of answering that question.

Passive, if not overtly servile, we revel in the Royal Family as an essential token of Englishness concealed inside an ever-flimsier veneer of (Great) Britishness. We wallow in the ancestral rituals, in the faint odour of Alfred’s burned cakes. We behold the jewelled sword, the ointment, the screen, the robes and sceptre, and we tell ourselves that these things define us and bind us together as a country, and make us better than other countries.

We delight in what the Guardian’s theatre critic Michael Billington called the ‘Shakespearian’ coronation defined by ‘pageantry, procession, music, and mystery’. We camp out all night to catch a glimpse of ‘history’, forgetting that history is something that is made by the decisions taken or not taken by millions of people, not by a pampered and petulant upper class twit with a fountain pen.

Rather than make history ourselves, we prefer to be spectators of the great men and women who supposedly make it. We gape at the druidical rites of ancient Albion, and count off the celebrities and world leaders who confirm its greatness. Incurable romantics, in a Mills and Boon kind of way, we seek the look of love in Prince William’s face or Kate Middleton’s smile. Mesmerised by our ineffable grandiosity, we prefer the smell of incense to the stench of a decaying nation, the robes of priests and archbishops to the suits of our elected politicians.

We marvel at the ridiculous ‘Tory women’, as the Mail called them, in their coronation hats; at the ghastly shower of prime ministers who have wafted through Downing Street over the last twelve months. We watch Penny Mordaunt holding a sword and hey presto! it’s obvious that a woman who can do that must be prime ministerial material.

Perhaps there were those who just wanted to look up at the rainy skies, as Dan Wootton did, skulking in the crowds like some malignant ghoul, and imagine that the raindrops were Meghan Markle’s tears as she contemplated our greatness from Archie’s birthday party. Or perhaps we just needed a break, an escape from what Sarah Vine called the ‘myriad worries that assail us daily’, because there’s nothing that a little bunting can’t heal, and after all, as Lady MacGove pointed out, the coronation was ‘Britain at its most optimistic and spectacular’.

One thing is for sure: when someone uses language like that, they are probably not particularly ‘assailed’ by any worries at all, and don’t think for an instant that are worried about you. And you can also take it as a pretty safe bet that the new king is not that worried about you either, and is more concerned with his leaking fountain pen. Yes, His Majesty talks loftily about ‘service’, and perhaps he actually believes. Of course he wants us all to be ‘volunteers’, and perhaps the Queen Consort can discuss these possibilities next time she lunches with Piers Morgan and Jeremy Clarkson.

But if the once and future king really cared about the very serious state many of our communities are in right now, he wouldn’t have made us pay for a coronation that he has more than enough money to pay for himself, and he might even have made a donation to a foodbank or two.

And volunteering is all very well, but volunteers can’t drive ambulances or check your eyesight or pay your bills. As for ‘service’, tell that to the nurses and ambulance drivers and all the millions of people up and down the country who serve every day for much less than they deserve, and a lot less than most of the guests at the coronation will be getting, and a lot less than the government is willing to give them.

The injustice of all this stares us in the face; yet millions of don’t want to see it. They prefer the bunting, the flyovers, the Household Cavalry, and the ‘optimism’ that such things supposedly express. Call me a ‘naysayer’, as Sarah Vine would have it, but these aren’t the things that make a country great, and they aren’t the things that a country in deep crisis should be placing such importance upon.

Unwilling to even think of moving towards a more equal society; unable to transform our corroded institutions or fix our broken country; unable to face up to our legacy of political, military, and economic failure, too many of us prefer magic and mystery, ritual and drama. Too many prefer to take comfort in reactionary notions of continuity and tradition, rather as the disturbing questions about why a country that should be so much more than it is, is visibly failing to protect or show even basic solidarity to so many of its citizens.

As Penny Mordaunt might have said, nor shall my sword sleep in my hand/till we have built Jerusalem/in England’s green and pleasant land, but that will not be happening in the near future. And it will not be would-be Tory contenders or crowned kings, or any amount of magic and mystery, who will bring that possibility any closer.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

April 27, 2023

Argentina 1985

Of all the southern cone dictatorships of the 1970s, the Argentinian iteration was the cruellest and the bloodiest. It was also the most devious, cunning, and depraved. Unlike Chile, there were no air strikes on the presidential palace to attract negative international attention. The junta that took control of Argentina in 1976 did so with the seamless serenity of a genteel change in management, accompanied by a few tanks.

It was a coup that many Argentinians had anticipated, and were many people like Borges and Jacobo Timmerman, who initially supported it, and welcomed the calm it seemed to bring to a nation plagued by political violence.

To do those who wanted to look closer, it was clear what the military junta intended to do. In 1975 General Rafael Videla told a gathering of Latin American army officers ‘As many people must die in Argentina so that the country will again be secure.’ Before the coup, Jacobo Timmerman - acting in his capacity as newspaper editor - had lunch with a naval officer, who told him that the armed forces intended to eliminate all suspected terrorists. When Timmerman asked what he meant by ‘all’, the officer replied, “All ... about 20,000 people. And their relatives, too - they must be eradicated - and also those who remember their names. ...Not a trace or a witness will remain.''

Timmerman didn’t foresee that he himself would be arrested and tortured, and only narrowly escaped becoming one of these people. And yet the military was true to his interviewee’s word. Where the Uruguayan military relied mostly on torture and imprisonment in its dismantling of the Tupamaros revolutionary organisation, the Argentinian military tortured and then killed most of the people it had tortured, without ever admitting that it was doing it.

The result as the writer Ernesto Sabato put it in his prologue to the CONADEP (National Commission on the Disappearance of persons) Nunca Mas report was a ‘demented generalized repression’ and the most terrible tragedy in Argentinian history.

The crimes carried out by the Argentinian military were so shocking that they challenge our understanding of what it means to be human, and they can easily elude the ability of those who did not witness them to understand how such crimes could have happened.

As CONADEP noted in its report

the men and women of our nation have only heard of such horror in reports from distant places. The enormity of what took place in Argentina, involving the transgression of the most fundamental human rights, is sure, still, to produce that disbelief which some used at the time to defend themselves from pain and horror. In so doing, they also avoided the responsibility born of knowledge and awareness.

These observations should not be limited to Argentinians. When governments perpetrate crimes against humanity, the ‘knowledge and awareness’ of such crimes should not be confined within national borders. But there are certain crimes that are too painful to think about, or which seem to be beyond the reach of the human imagination to encapsulate. Writing of the torture of whole families that he witnessed during his own detention, Jacobo Timmerman described how

The entire affective world, constructed over the years with utmost difficulty, collapses with a kick in the father's genitals ... or the sexual violation of a daughter. Suddenly an entire culture based on familial love, devotion, the capacity for mutual sacrifice collapses.

This year, international cinema audiences were given a rare insight into the world in which such things became possible, in the Oscar-nominated film Argentina 1985. Driven by the great Ricardo Duran’s riveting performance, it revisits the trial that sent Videla and the leading members of the military junta to jail. It’s a moving and uplifting film, with a hopeful message that is derived in part, from the young lawyers who helped prosecutor Julián Strassera assemble his case, and also from the fact that it has a ‘happy’ ending – the generals are convicted. Argentina’s democratic institutions triumph. Catharsis has been achieved.

The film has been criticized in Argentina for not referring to the work of CONADEP – the National Commission for the Disappeared – whose investigations provided so much of the material that was used to indict Videla and his cohorts. At the same time it has been viewed by more than 1 million Argentinians, many of whom will have no knowledge of the horrendous events that took place in their country between 1976-83. One member of the Mothers de la Plaza de Mayo praised the film, and said that she and many other activists were particularly grateful for it at a time when many of them are infirm and very old.

Far be it from me to question such responses. Argentina 1985 deserves all the praise it has reserved, and it should have been an Oscar-winner. But as good and as important as it is, it is also a limited film, precisely because it is an audience-pleasing film. It’s an Argentinian film that appeals to a longstanding Hollywood convention: the dogged hero-lawyer who overcomes fear, threat and danger to bring about justice, whose final ‘nunca mas’ speech provides the dramatic apotheosis and also a comforting message to take home from the cinema.

But despite the harrowing testimonies from some of the defendants, I would argue that the courtroom conventions and the trial’s focus on the leaders of the dictatorship rather than its lower-level protagonists, serve to keep the audience at a safe - and comfortable - distance from the crimes it describes. The film refers to historical events and real people. It tells - or rather reminds - its audiences what happened, but it doesn’t look too deeply into why or how it happened.

Some might think ‘good thing too’ - who wants to watch people being tortured or thrown drugged out of airplanes? What cinemagoer could bear to see what Jacobo Timmerman and others were forced to see? Aren’t there certain acts that cannot be described on the page or on the screen, without incurring the risk of voyeurism or doing disservice to the victims?

Such reservations are valid - up to a point. But it is sometimes necessary, if we are pay due diligence to the truth of history - no matter how awful - and the fate of its victims, then from time to time we need to look that history in the face, and we need artists and writers who can help us do that.

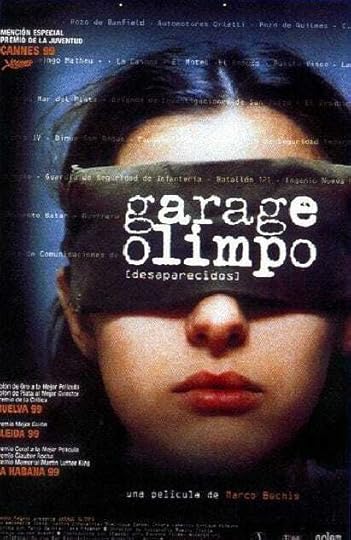

I recently watched Garage Olimpo, the 1999 film by the Chilean-Italian director Marco Bechis, which shows the hidden world of one of the clandestine detention centres set up by the Argentinian dictatorship in a garage to torture and murder their opponents. Bechis was a prisoner in one of these centres himself, and was only released because of his Italian passport, and because his father, a high-level functionary for FIAT, was able to bring about pressure for his release.

So this is a director who knew what he was talking about when he made this profoundly disturbing film which takes the viewer deep into the dark and rancid heart of the dictatorship’s killing machine. The plot revolves a twisted ‘love story’ between a kidnapped activist and her torturer. Such relationships were not unknown during el proceso. There were cases in which female detainees who had been kidnapped and raped formed relationships with their torturers.

But Bechis did not make his film as a voyeuristic melodrama. This is not The Night Porter. There is no kinky sex and no scenes of actual torture, though enough is revealed to make it horrifically clear what is taking place. In revealing the inner workings of a clandestine detention centre, Garage Olimpo shows the banal ordinariness of the ‘task forces’ who kidnap, torture, and ‘transfer’ (ie. kill) their victims in a relentless production line.

It’s a system that operates according to lists and quotas. No sooner does one car bring its latest blindfolded victims to the garage, to be told by the commanding officer that they are now ‘at the disposition of the federal executive power’ than the kidnappers are off again, working through the other names on their lists. No sooner has one group of prisoners been tortured and their ‘information’ squeezed out of them, then they are given an injection, and placed in the trucks that will take them to the planes, waiting to toss them alive into the sea.

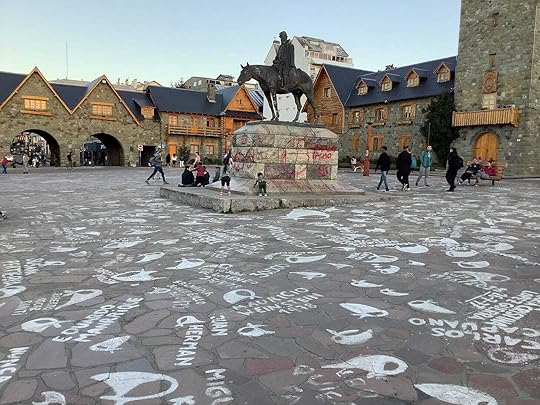

We tend to think that the people who carry out such actions must be monsters and sadists, and some of these task force kidnappers and torturers clearly are. One guard is an out-and-out gangster, who forces relatives of his victims to sell them their houses in the hope of saving their loved ones, and then shoots them. Others are ‘violence workers’, as Martha Knisely Huggins and her colleagues once described the Brazilian torturers they studied. These are men who torture and kill in shifts. They listen to rock and roll on the radio. They play ping pong during their breaks while prisoners are being tortured.