Matthew Carr's Blog, page 9

June 4, 2024

No Fascist Groove Thing

I’m currently reading Antonio Scurati’s docu-novel M: Son of the Century. It’s a beast of a book, and longer than it needs to be. But it’s also a spellbinding account of the rise of fascism in Italy between 1919 and 1925, which feels disturbingly relevant to our own fractured political times.

Scurati reminds me of Eric Vuillard, in the way that he imaginatively re-inhabits history and merges fiction and documentary. His book is based on prodigious research, with actual historical quotes buttressing each chapter But Scurati is a creative writer, with a novelist’s ability to transport 21st century readers into a past that many of us have forgotten or never knew existed, or simply took for granted.

It’s not a pleasant sensation to spend more than 700 pages inside fascism’s head, but that’s where Scurati takes you, and for anyone wanting to understand the diseased politics of our own times, it’s worth sticking it out.

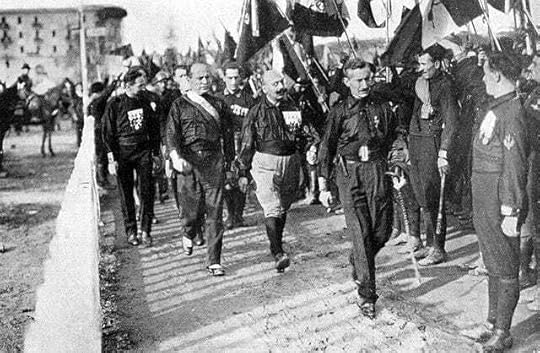

As the title suggests, Scurati focuses his attention primarily on Mussolini himself, and depicts the rise of the fascist movement in its early phases from the point of view of the future dictator. Scurati’s Mussolini is a loathsome and repugnant character, a cunning Machiavellian bully surrounded by a cast of equally despicable monstrosities: The priapic war junkie Gabriele D’Annunzio; the vain thug Italo Balbo, and the hysterical Futurist Marinetti are among the psychopaths, killers, and fanatics who make Tommy Robinson and the EDL look like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

The Italian political class is fatally unable to deal with what was then a historical novelty - a militarised mass political movement for which, as Scurati explains it ‘politics is a form of civil war against one’s adversaries portrayed as enemies of the nation’. Only the doomed socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti emerges with any integrity from the politicians who succumb all too easily to Mussolini’s appeal.

Scurati shows the factors that enabled that appeal: a bitter post-war ‘victory’ that was not accompanied by any tangible achievements; the vengeful paranoia of the lower-middle classes as living standards collapsed; the collusion between the aristocracy and fascist thuggery in suppressing working class militancy and peasant activism.

As historically-specific as it is, Scurati’s fascist movement shares many of the features we have come to associate with its 21st century variants: the contempt for liberalism; the truth-twisting dishonesty; the primitive machismo and misogyny; the fake-victimhood; its chest-beating nationalist chauvinism; the sadism and violence.

To those who still think that Italian fascism was relatively mild in comparison with Nazism, Scurati’s unsparing account of the reign of terror imposed by the squadristi ‘extermination groups’ in the Italian countryside is a necessary corrective. These were years when truckloads of fascist ‘extermination squads’ went out at night to murder, torture and humiliate peasant league activists, socialists; when schoolteachers were shot dead in front of their kids, and even MPs could be picked up in the street and beaten up, and in the case of Matteotti, brazenly murdered.

The Black Shirts, like the Freikorps and the Nazis, emerged from the brutalising experience of trench warfare and industrialised mass killing. Their cadres were already steeped in blood even before they waged ‘war’ in the streets against the leftists and liberals they regarded as traitors.

21st century pre-fascism, if I can call it that, has different sources: sitting room sofas, pubs, thinktanks, person shooter games, whackjob podcasts, alt-right websites, Twitter, and YouTube conspiracy videos, MAGA rallies and the occasional gun club. It doesn’t have any equivalent to the mass violence of the squadristi - yet.

The January 6th rioters, the Proud Boys, the Charlottesville Nazis, and the anti-Black Lives Matter mobilisations are perhaps the nearest thing we have to the squadristi, but that shouldn’t be room for complacency. It’s easy to laugh when infantile poseurs like Liz Truss talk of using ‘bigger bazookas’ against the left, but as insolently stupid as she is, she knows there is an audience for talk like this that is more serious than she is.

Like its twentieth century predecessors, it’s an audience steeped in paranoia, hatred, and faux-victimhood, that dreams of purges, deportations, detention camps, civil wars, and a reckoning with the ‘libs’, the ‘communists’, the ‘cultural Marxists’ and the wokeist elites.

Like Mussolini’s fasci, they’re tough guys, or they think they are - real men who never bend the knee, and despise the ‘feminazis’ who make men ‘soft’. They gather in herds -digital or in the flesh - and think and behave like cultists, projecting their toxic political aspirations onto freakish monstrosities and political fakirs like Milei, Trump, or Abascal.

Like Mussolini’s fascists, these are movements that use the instruments of liberal democracy to destroy democracy and bend its institutions to their will. Descendants of a tradition that concocted fake Jewish conspiracies as a justification for murder and genocide, they now cheerlead the Israeli Sparta for murdering Palestinians who they regard only as ‘Muslim terrorists’ and condemn those who protest these killings as ‘hate mobs.’

Even in a world where communism is virtually non-existent in comparison with 1919, these ‘populists’ see communists and ‘cultural Marxists’ everywhere, and sinister ‘elite’ conspiracies everywhere. Take the response to Trump’s sordid court case last week. Found guilty by a jury on all 34 counts, the Trump-creature immediately declared himself the victim of a witch-hunt and proclaimed America to be a fascist state.

His entire party, accompanied by the usual media outlets, swung in right behind him, to the point when anyone could be forgiven for thinking that Trump really is Mother Theresa or Jesus. There is, at present, not the slightest indication that Republican voters will be swayed by the verdict. Over here, Nigel Haw Haw, Russell Brand, and the blonde custard man who used to be our ‘prime minister’ all described the verdict as a ‘hit-job’, because these are men who can smell the fascist stench and hope to benefit from it.

They know that if Trump-Jesus wins, his administration will be an administration bent on vengeance and retribution; that he will intimidate and seek to silence any institutions that refuse to bow to him. They know that Trump has promised to ‘crush’ pro-Palestinian demonstrators, and use the National Guard to deport 11-15 million immigrants he regards as criminal ‘invaders.’

They know, but they don’t care, and the terrible tragedy of our times is that too many other people don’t care either.

TelemeloniAntonio Scurati does, and M: Son of the Century is an urgent warning to the present, from a country governed by a party that derives directly from the fascist tradition, and which has developed a fondness for strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) to shut down criticisms.

Roberto Saviano was recently fined 1000 euros for calling Meloni and Matteo Salvini ‘bastards’ over their condemnation of NGO-run ships carrying out search-and-rescue in the Mediterranean. In April a university professor was accused of defamation by one of Meloni’s ministers because she accused him of sounding like a ‘Gauleiter’ when he alluded to the ‘white replacement’ theory. That case was thrown out last month, but it probably won’t be the last.

On April 25 Antonio Scurati recorded a monologue for the RAI tv network on the anniversary of Italy’s Liberation Day, in which he described fascism as ‘an irredeemable phenomenon of systematic political violence characterized by murder and massacres’ and accused the ‘post-fascist ruling group’ of rewriting history rather than repudiating its neo-fascist past.

Scurati’s indictment left no room for ambiguity:

After having avoided the topic during the electoral campaign, Italian Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni , when forced to address it on the occasion of historical anniversaries, obstinately stuck to the ideological line of her neo-fascist culture of origin: she distanced herself from the indefensible brutalities perpetrated by the regime (the persecution of the Jews) without ever repudiating the fascist experience as a whole. She blamed the massacres carried out with the collaboration of Italian fascists on the Nazis alone. And finally, she ignored the fundamental role of the Resistance in the rebirth of Italy.

Scurati also criticized Meloni for not using the word ‘anti-fascism’ in her own Liberation Day address, and insisted that until this word was ‘pronounced by those who govern us, the spectre of fascism will continue to haunt the house of Italian democracy.’

Brave words, but Italians never heard them, because RAI didn’t broadcast Scurati’s monologue that night, or any night. It was taken off air, and that is one reason why the RAI broadcasting service is known to its critics as ‘telemeloni’. But Scurati is right: anti-fascism should be our watchword too. There is no magic cure to the disease that western democracies are suffering from, but these movements cannot be defeated by ‘centrist’ parties that ape their nationalist positions, engage in performative demonstrations of liberal toughness on immigration and ‘welfare scroungers’ - or by authoritarian purges to cover up collusion in the Gaza massacres.

Nor can they be defeated by the left alone. We need broad progressive alliances and movements, nationally and internationally, that can reach as far as possible across the spectrum, to combat the anti-democratic forces that are vying for power across the world. Few people will be reminded that this is not happening.

In America, the Biden government is drifting with shocking complacency towards defeat, draining vital votes and support because of its abject complicity in the Gaza massacres, and putting up a leader who has long since passed his sell-by date. In the European Union, Ursula von der Leyen has spent the last year trying in vain to cultivate a political alliance with Georgia Meloni. In Spain, the supposedly mainstream conservative party has colluded with Vox fascists in presenting Sanchez as a traitor and in the vicious character-assassination of his wife. In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally is poised to make huge gains in European elections and possibly French elections too.

And here in the UK, the Labour Party continues to marginalize and humiliate the left as it seeks to win from the centre - seemingly unaware that the centre is no longer what it used to be. It’s all very well getting banner headlines in the Sun promising to cut net migration, announcing that a Labour government may also ‘offshore’ asylum seekers, or promising to ‘work with whoever is elected president.’

But if Trump wins, the UK will find itself adrift - caught between a European Union that it has cut itself off from - dominated potentially, by the far right, and a fascistic Trump administration whose only interest in the UK will be what it can get for itself. It will face potential challenges, not from a chastened Conservative Party that has returned to ‘normal’, but from a radicalized party emboldened by a Trump victory.

In these circumstances, a Labour government will have to decide what side it is actually on, and show leadership, vision and principle in the face of this global anti-democratic authoritarian onslaught. Scurati’s brave book is a painful reminder of what can happen when democracies fail to do that. I would recommend that Labour politicians read it over the summer holidays, following what I hope will be a Tory wipe-out.

But I suspect that such a recommendation would fall on deaf ears.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 28, 2024

Rainy Day Tories

Credit: Youtube Screenshot

Credit: Youtube ScreenshotRain and the movies have a long and distinguished history, with many different moods and permutations. Gene Kelly dancing; the romantic rain of Four Weddings and a Funeral; the dystopian drizzle of Bladerunner; the vengeful downpour of The Unforgiven, or Andy Dufresne’s ecstatic moment of liberation in The Shawshank Redemption - rain can always add something extra to a story.

In politics, however, rain is something you generally want to avoid. Because if you do find yourself standing in the rain without an umbrella to announce a general election, it is only ever likely to be a pathetic fallacy - a confirmation of your foolishness, lack of preparedness, poor choices, and perhaps a sign that the gods have abandoned you.

This was how it was on Wednesday, when a sodden Rishi Sunak stood at the lectern with the strains of ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ ringing in his ears and pulled the plug on one of the most calamitous eras in British politics. Watching the Head Boy robotically intoning his Bold Plan while the rain rolled down his tailor-made suit, we all knew that the end was in sight, and the dismal look on his face suggested that he did too.

It was an extraordinary move that took the country, the opposition, and his own party by surprise, and suggested that Sunak has as much contempt for his own MPs as they have for him. It was simultaneously feckless, reckless, exhausted, thoughtless, and desperate. Insofar as there was any political calculation behind it, we can only assume that Sunak hoped that at least the students would be off on their holidays by July 4th and not bother to vote.

Beyond that, the date appears to have been decided according to a scale that begins with awful and ends with wipe out. That same evening, Sunak had a Sky journalist forcibly ejected from his campaign launch in front of the cameras. There were rumours that Tory MPs were planning to unseat Sunak in order to install a successor who would cancel the election.

Perhaps even these plotters realised that unseating your own unelected PM to cancel an election is not your smartest move. But even as the party scrambled to find 200 candidates to fill vacant seats, more vacancies were coming available, as MPs and cabinet ministers deserted the sinking ship with an alacrity that can only be described as indecorous.

Within days Redwood, Leadsom, and Gove had decided not to defend their legacy or fight for Sunak, and they probably won’t be the last to make the jump. No one will be surprised that Boris Johnson will also be absent from the campaign, according to the Mail, because he has ‘booked a series of foreign trips that will take him out of the UK for the majority of the critical period.’

If Johnson thought it was in his interest, you know those trips would swiftly be cancelled. But who would want to get involved in this campaign-of-the-damned, or defend their party’s record, when you yourself helped destroy your own government? Better to slope off and let the whole thing crash and burn, and hope that you can avoid being associated with the wreckage and come back later when it’s all been forgotten.

Even Farage, another great English patriot, decided that working for Trump was better than putting himself up for a candidate as a representative of the ‘party’ that was supposed to outflank the Tories from the right. That left only the Head Boy and his advisors to steer the Tory ship through the reefs, and the evidence suggests that is not a task for which they are not well-suited.

By the end of the week Sunak had headed off the Titanic Quarter in Belfast for a walkabout, because what better way to generate some positive headlines? He also managed to get himself photographed in Morrisons, so that only the word ‘Moron’ was visible above his head. At a food distribution centre in Derbyshire he interviewed high-viz jacket ‘ordinary people’ who turned out to be Tory councillors. Footballing man of the people that he is, he asked some Welsh voters about their chances in the Euros, only to discover that Wales have failed to qualify.

And on Saturday he took the day off for a brainstorming session with his advisors, emerging the next day with a plan to introduce compulsory military service for eighteen-year-olds.

Genius. Never mind that these are the politicians who removed the freedoms that once young people to live and work anywhere in Europe, and then turned down an off for a new visa scheme for 18-30s. Now they want to bring back national service to ‘foster a culture of service’ and make society ‘more cohesive.’

By the end of the day Sunak’s plans had been attacked by a Tory defence minister, a former admiral, a former chief of the general staff, and Nigel Farage, who said, correctly, that they were an appeal to ‘his’ voters. Meanwhile, Sunak’s team were out on in the tv studios, attempting to explain that a)the scheme wouldn’t be compulsory, b)maybe there would be a little compulsion c) it wasn’t clear what kind of compulsion it would be.

If they knew the answers, we don’t, and we probably never will. Because this is the kind of policy you will unroll if you assume that all British voters are a sclerotic pensioner in a pub somewhere in Buckinghamshire already on his third pintat midday, nursing memories of old John Mills films and complaining that the country has gone to the dogs and there’s no respect, and national service never did him any harm.

It’s too easy to imagine Sunak and his advisers holed up in a country house with the spin doctor Stewart Pearson from The Thick of It. Family badger culls? A referendum on hanging? Force asylum seekers to pick fruit? Assisted dying for the long-term unemployed? Fines for foreign languages speakers? When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose, but it’s hard to see what a government this clueless can do in the next five weeks to reverse the polls that point almost unanimously to a crushing defeat.

Rarely have defeat and humiliation been so richly-deserved. I have spent most of my adult life under Tory governments, but I have never known anything like the last fourteen years.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It’s been a wild, spirit-crushing ride from the Big Society to the vicious, pointless cruelty of austerity that made the most vulnerable people in society pay for a crisis they had not caused. The persecution of ‘welfare scroungers’ was accompanied by thenscapegoating of migrants and asylum-seekers, culminating in Cameron’s hapless, ill-considered flutter at the Brexit casino, and the years of lying, gravity-defying parliamentary fights and pseudo-fights that followed.

The arrogance and stupidity of men like Davis and Frost; the corruption and the toleration of corruption; the depraved, decadent premiership of Johnson; the gross mismanagement of the pandemic; the gormless fanaticism of Truss and Kwarteng; the foolish cruelty of the Rwanda policy; the anti-woke culture wars; the near-collapse of the NHS, the police, the social care sector and the criminal justice system; the spread of hunger and poverty in a developed country - all of these outcomes are part of the Tory nightmare we have yet to wake up from.

And throughout these years, we have had to endure a procession of the most dismal liars, chancers, and mediocrities that have ever marched through British public life. Dowden, Braverman, Patel, Francois, Gullis, Bradley, Clarke-Smith, Jenkyns, Dorries, Atkins, Whately, Jenrick, Rees-Mogg - the list is endless and endlessly shameful.

These are the scrapings of a discombobulated party that has driven out politicians with even a modicum of honesty, integrity, competence, and good sense, leaving only the shriekers, the shouters, and the oleaginous grifters to represent a dazed, disorientated, and punch-drunk country that has only just begun to understand how far it has fallen and how foolish it was to place its fate in the hands of such people.

Fourteen years after Cameron asked voters to choose between ‘stability and strong government’ and the ‘chaos of Ed Miliband’, the UK is a country where the NHS has 121,000 staff vacancies and waiting lists are double what they were in 2010; where dental care is so difficult to get that people are pulling out their own teeth without anaesthetic. It’s a country of food banks, crumbling schools, teacher shortages, record levels of household debt, soaring rents, and stagnant wages, where sewage-polluted rivers seas have become a symbol for the absence of corporate accountability and a metaphor for the national predicament.

All this is the responsibility of the party that has ruled the country for the last fourteen years, and that now has the audacity to ask for another five. For all these reasons, the Tories have to be not merely defeated, but annihilated on July 4th. And yet there is a curious disconnect between the scale of the disaster and the low-key tone of an election campaign that feels more like a weary change of management, than the significant social or political shift that you would expect to find after these calamitous years.

The main beneficiary of the Tory Party’s headlong descent into the void has been the Labour Party. On one level, it’s a remarkable achievement to be in the position that Labour is in - poised to reverse its historic defeat in 2019 within a single electoral cycle. Labour has achieved this, partly by purging itself of every trace of the Corbyn project, and partly by skilful politicking that has enabled the party to present itself as the only credible alternative to a Tory Party that has lost its collective mind as a result of Brexit.

The four Tory governments that followed the referendum all owed their existence to Brexit, and between them they have so discredited and divided their party that neither their centrists nor their extremes can stand its latest iteration. Gone are the virtues that were once associated with the Tory moderates and the one-nation conservatives: a sense of duty and commitment to public service, competence, expertise, and caution; a wider sense of the national rather than party interest anchored in real possibilities rather than fantasies.

Having jettisoned all that, the Tories became the maniacal, hollowed-out, gutted wreck that is now seeking to win the next election - a party of chancers, incompetents and culture warriors who either shared in the Brexit fantasy, or pivoted towards it because it served their ambitions, or lacked the courage to take responsibility for the damage that Brexit had inflicted on the country.

You would have to be a spectacularly terrible opposition not to capitalize on this. Electorally-speaking, the centre ground, even the right-of-centre ground was there for the taking, and Labour have occupied it by becoming everything that Conservatives were once supposed to be. No wonder David Lammy boasted in the US that he was a conservative with a small c.

In purging itself of the left and engaging in performative punishment of the left to attract these voters and neutralise the right-wing press, Labour has successfully made itself appealing to Tory voters who can no longer stand their own party. If the polls are to be believed, Labour stands on the brink of unravelling the 2019 Johnson coalition that some Tories once believed might represent a permanent shift in their favour.

This should be good news, and yet it doesn’t feel as good as it should, partly because Labour has co-opted so many Tory nostrums - iron fiscal discipline, strong borders, private sector involvement in the NHS, flags and patriotism etc - that its mantra of ‘change’ doesn’t feel like much more than a change in personnel.

It’s effective politics to neutralise so many Tory attack lines, to the point when Sunak’s only current attack line is that it doesn’t know what Starmer stands for. As Chris Grey has pointed out with his usual meticulous logic, Labour has successfully prevented the Tories from turning the election into a ‘protect Brexit’ battle - possibly the only strategy that might have enabled them to rally the troops.

But strategic cleverness doesn’t necessarily translate into progressive government. You might win an election by avoiding elephant traps, dodging negative headlines, and writing columns for the Sun and the Daily Mail, but these newspapers will never be Labour’s friends. A Labour government will have to take decisions, and not merely the usual ‘difficult decisions’ such as rejecting doctors’ pay demands. It will have to make peoples lives better, and show them that government has their interests at heart. It will have to fight fights that need to be fought, and it will be attacked by powerful people and institutions that are more likely, in normal conditions, to see the Tory Party as their chosen instrument.

Labour will also have to give people a reason to trust and believe in it, not once, but twice, and hopefully more than that, because the UK cannot be turned around or moved to a better place in five years.

It’s a natural instinct, especially after so many years of catastrophic misgovernance, to hope that the next government will be better than the last, and for this reason it is profoundly depressing to see the likes of Natalie Elphicke being welcomed into the party, or read Rachel Reeves assuring Daily Mail readers that Labour will not be profligate with ‘your money.’

No one is asking Labour to be ‘profligate’, but money needs to be spent just to repair the damage to public services, let alone improve them, and unless that happens, no genuinely progressive government can expect to maintain public support for long. Reeves has said that an incoming Labour government will not continue with austerity, but it’s difficult to reconcile Labour’s pledges to reduce all taxes for working people, and use construction-based ‘growth’ to find money for public services.

It’s wearying to hear an incoming government talk about growth in an era of climate breakdown. We need a conversation about inequality and distribution and climate change mitigation. We need a government will fight with teachers, doctors and nurses and not against them, that will help young people buried under high rents and tuition fees who cannot buy houses, as well as the usual fagged-out cliche of ‘hard working families.’

We also need an honest conversation about immigration. Because the Rwanda plan may be an open goal, but if Labour continues to use the same tired language about toughness on criminal gangs that Blair and Brown once used, then it will find itself in the same quandary that harmed Labour in the past- a government that privately recognises the need for immigrants, but cannot admit it publicly.

The UK cannot continue to be a country that needs immigrants and simultaneously treats immigration as a crisis and a burden. This is one reason why we got Brexit, and Brexit remains the elephant in the national room that Labour will have to address at some point, even if they don’t want to address it now. In the same week that Sunak made his announcement, David Lammy and Stephen Kinnock were in the US visiting the Heritage Foundation - one of the most dangerously anti-democratic thinktanks in the US - to discuss the prospect of a future US-UK trade deal with Trump.

Does Labour seriously believe that the UK would get a deal from Trump that would benefit the UK, let alone a deal that would compensate for what has been lost? Why are Labour politicians even meeting such people? If Labour wins, it will be one of the few (nominally) social-democratic parties to win an election in the coming months. It will find itself in a world menaced by authoritarian right-wing political movements of the type that the Heritage Foundation supports. I haven’t seen or heard a single thing - either under Corbyn or Starmer - to suggest that Labour even recognizes these dangers or has any strategy for fighting them.

To govern this fractious country in times like these will require more than competence and a safe pair of hands. It will require honesty, vision and principle, and an ability to build alliances both at home and abroad. And if a Labour government fails and gets the blame for everything the Tories have done, the wounded beast may come back, even more feral and more extremist that it already is.

When Attlee came to power in 1945, Labour could count on soldiers’ votes, the experience of war-time national planning, the determination not to return to the thirties, and a public that wanted to see major changes in the way British society was run.

We aren’t in that place at all in 2024. Maybe that’s why the main emotion I feel at the thought of the election is not hope, but schadenfreude. Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver once thanked God for ‘the rain which has helped wash away the garbage and trash off the sidewalks.’ Like millions of people, I want to see the Tory trash washed off our sidewalks. I want to see once-safe seats fall, Portillo moments squared, the end of careers that should never have become careers in the first place, and some kind of reckoning for the last fourteen years.

I hope voters across the country will vote for whoever is most likely to achieve that outcome. Because whatever Labour might or might not do, one thing is certain: there is not the remotest possibility that things will get better under this party-of-the-damned that has so disgracefully mismanaged the power it should never have been given.

And so whatever my misgivings about the government that takes its place, I’ll take the schadenfreude, because it’s the endless tragedy of British politics that you very rarely get much more than that, and if you hope for too much, you are very likely to be let down.

May 21, 2024

The Talented Mr Hari

If there’s one thing I can’t abide in politics or life, it’s fakery. This aversion has nothing to do with my political allegiances. I dislike fakes who supposedly represent ‘my side’ just as as much as I dislike them on the other. When I say fakery, I mean the term in its most basic dictionary sense as ‘a thing that is not genuine, a forgery or a sham.’

Every era has its share of people who fit this definition, but our shallow, distracted-addicted age has more fakes than most. It’s the golden age of the grifter, the huckster, the carnival barker, the snake oil vendor, the chancer and the fast-buck hustler. It’s an age in which slippery dishonesty, duplicity and the absence of a moral compass will never be impediments to self-advancement as long as you aren’t caught out, and will generally not be held against you even if you are.

Last week, languishing in my sickbed with COVID, three examples of a particular kind of ersatz leftism came drifting unasked into my Twitter feed. First up was Paul Mason, announcing that he was putting himself forward as a Labour nominee to run against Jeremy Corbyn in North Islington. This is Mason’s fourth attempt to get a safe seat under Starmer, who has taken Corbyn’s place in his affections. Mason has previously tried Manchester and Wales. He once came up here to Sheffield, even though there was already a very popular local candidate in the district he was trying to parachute into.

He didn’t get the nomination, and now this ridiculous carpetbagger wants to oppose Jeremy Corbyn, the man who he once hailed as the saviour of the working class, in Corbyn’s own constituency. Maybe there’s been some kind of political journey there, but all I see is craven opportunism and a tedious craving for attention that will seek an outlet in whatever spaces appear, and tailor its politics accordingly.

Then there was Russell Brand, another former revolutionary messiah, now alleged rapist and swivel-eyed conspiracy theorist, engaging in some kind of Christian Bros immersion in the Thames with Bear Grylls and some other sinner. So much repentant tattooed flesh in those toxic swirling waters was enough to make the angels weep. But it will take more than the Thames - especially nowadays - to wash off the unmistakeable stench of grift from Brand’s Damascene photo-op.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

And in the same week, up popped Johann Hari, perhaps the most brazen grifter in the history of British journalism, promoting his new book in the way that only he can. Hari has written that the food critic Jay Rayner once took the weight-reducing drug Ozempic, a claim that Rayner denied in a tweet that accused Hari of talking ‘complete and utter bollocks’. Hari apologised and blamed his fact-checkers, and said that he had actually confused Rayner with the writer and critic Leila Latif. His apology was marred somewhat by the fact that he spelt Latif’s first name wrong, and it then transpired that she had not described taking the drug Hari was referring to.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance FactcheckerFew people who know anything about Hari will be surprised by this car-crash. Something like it happens whenever he publishes a book. Every writer makes mistakes, even we don’t all have fact-checkers. I have been saved from humiliation on more than one occasion by editors who spotted mistakes I made before the books went into print, and there have been mistakes that have got through. But when that happens, the mistakes are ultimately mine, not the editor’s. The problem with Hari is that he has been making ‘mistakes’ for a very long time, and I’m not talking about typos or the occasional incorrect date or reference.

In 2011, Hari was (belatedly) investigated by the Independent after it became an open secret that he had been inserting quotations from his interviewees’ books or articles in his own interview/profiles and then passing them off as his own quotes. It seemed then, that he was finally about to get the comeuppence that many people thought he deserved.

I was definitely one of those people. I never admired or respected Hari’s writing, and most importantly, I never trusted him, even when I agreed with what he was saying. It wasn’t just the arrogance and self-regard, the wheedling, bombastic prose, or Hari’s eager sixth form enthusiasm for aerial bombardment - I mean, he once suggested that the West should bomb North Korea as well as Iraq. Too often, his reporting just didn’t ring true. Take, for example, the piece he wrote about Hamas and the Gaza Strip in 2006, in which he argued - correctly, in my view - that the West was making a mistake by ignoring Hamas’s offer of a truce with Israel. But his piece also contained an interview with a member of Islamic Jihad named ‘Abu Ahmad’, which included the following exchange:

“I want to kill and kill and kill again. I want to be a killing machine until, inshallah, I become a martyr,” he said, staring at me intensely. He is 27 – my age – and murderous. He has just described how he slashed the throats of four female Israeli soldiers in an illegal settlement in 2002, and he chuckled as he described how they cried for their mothers.

This atrocity was supposed to have happened in 2002. Except that there is no record that such an event actually took place in 2002 or in any other year, and you can bet that if four female Israeli soldiers had had their throats cut in Gaza, the world would have known about it.

Either Hari was really told this story by a fantasist, in which case he and his newspaper were too lazy to confirm its veracity. Or else Hari himself was the fantasist, and made up this Palestinian Psycho vignette to embellish his story. There are many other equally improbable stories from Hari’s reporting in those years, when he saw things that other people say he couldn’t have seen, or wrote down supposedly verbatim quotes that they turned out not to have actually said. And yet when the allegations against Hari became impossible to ignore in 2011, the likes of Polly Toynbee, Laurie Penny and even Naomi Klein fell over themselves to defend Hari, and said that his critics were jealous, homophobic, or political axe grinders.

Even when the Independent had to admit that most of the charges against him were true, it allowed Hari to issue a typically self-serving apology, which admitted that he had plagiarised, and also waged cruel ‘sock-puppet’ campaigns against people he disliked on the Internet, while still suggesting that he was some kind of victim. In accounting for his interview ‘technique’, Hari described how

When I recorded and typed up any conversation, I found something odd: points that sounded perfectly clear when you heard them being spoken often don’t translate to the page. They can be quite confusing and unclear. When this happened, if the interviewee had made a similar point in their writing (or, much more rarely, when they were speaking to somebody else), I would use those words instead. At the time, I justified this to myself by saying I was giving the clearest possible representation of what the interviewee thought, in their most considered and clear words.

This is the most pitiful sophistry. I’ve interviewed many people, and sometimes I wanted them to give me ringing or telling quotes, but interviews aren’t like the written word. People say what they say in a particular moment, and their utterances don’t always come out in the form of a golden quote. When that happens, you accept what you get and work with it. You DO NOT rephrase your subjects or put words into their mouth because you don’t think they’ve expressed themselves clearly or sensationally enough for you - unless, that is, you are so desperate for fame and fortune that you are willing to say whatever you think will get your story the most attention.

Also, if you quote from an interviewee’s books or articles, you make that distinction clear, you DO NOT take a quote from a book and then pretend that someone actually said it in your presence. My late friend Graham Usher lived and worked in the Occupied Territories as a teacher and a journalist for many years. Graham never studied journalism, but he became one of the most authoritative correspondents in the Occupied Territories. Graham would never have dreamed of doing even once, what Hari did on a routine basis, and the same could be said of any writer with even the smidgeon of integrity.

Neither Hari nor the Independent addressed the full extent of the allegations directed against him, which included borrowing whole chunks from other people’s books and articles and reproducing them wholesale; fabricating stories, meetings and incidents that never happened; and making some 600-odd edits of other people’s Wikipedia pages using the pseudonym David Rose.

The Independent didn’t sack him for any of this; instead it packed him off to New York to go on a ‘journalism course.’ Because that was what was wrong with their star columnist: he didn’t understand what journalism was. Like many others who followed this dismal saga, I was incredulous at the time, not at Hari’s slippery dishonesty - I already considered that baked in - but by the Independent’s cowardly face-saving. I predicted in my blog that the Independent had ‘done their hero more harm than good’, and that Hari would no longer have any future in journalism.

Boy, was I wrong about that.

Hari went on to become a bestselling author-cum-mental health guru, weaving pop culture, self-help takes on drugs and depression into international journeys of personal discovery. Various experts in the fields that he was ‘investigating’ questioned his research methods, his conclusions, and his sources. None of this mattered. Boosted by celebrity endorsements from Elton John, Hilary Clinton, and Noam Chomsky, for God’s sake, Hari shrugged off the cloud of ignominy like the Teletubbies baby sun. Millions of viewers watched his Ted Talk on addiction. He worked with Russell Brand - birds of a feather.

And now, nearly fourteen years after I predicted his downfall, he’s still here with the same ‘mistakes’ and the same bad-faith apologies, while his publishing company insist how proud they were to have published him. Hari is not without talent - and not only for re-invention - but there are plenty of talented writers in the world, most of whom would never do what he did. And in a world that valued and expected integrity from writers - or from anybody, for that matter - Hari’s ‘mistakes’ should have obliged him to seek another profession.

Shouldn’t there be space for forgiveness, you ask? Shouldn’t people be given a second chance if they genuinely repent? Yes. But the key word is ‘genuine’. And I have never read a word by Hari that suggests he genuinely repents anything, except that he got caught.

Such things matter, because if writing has any social or moral purpose beyond mere entertainment, it’s because of its connection to truth. This doesn’t mean that writers are always right. Or even that the truth is always possible. But writers should always strive to find it, when they put their thoughts onto the page or the computer screen. Writers - real writers - should not lie, not for governments or political parties or for self-advancement. They should not make stuff up. They should not copy or use other people’s work without acknowledging it.

If they do these things, in the pursuit of fame and self-aggrandisement, then they should be recognized for what they are: propagandists, court scribes, hacks, and grubby, dishonourable chancers. And if society is not willing to do that, then, as with politicians, it will get the kind of writers it deserves.

Such writers have always been around. There’s something of New Grub Street’s Jasper Milvain in Hari’s ruthlessly amoral quest for literary fame and fortune. But behind Hari’s ‘lost connections’ woo and the ‘stolen focus’ happy-clappy pieties about not spending time on the Internet, something else has been lost along the way - a basic moral compass. And I can’t think of Hari without thinking of Tom Ripley - another vindictive social climber and pathological liar with a penchant for false names and a taste for the high life.

Ripley inhabited other people’s lives - after killing them. Hari became rich and famous by divesting himself of all the ethical codes that writing should imply, and like Ripley, he got away with it. But integrity, once willingly given up, cannot be recovered, and no amount of reinvention can entirely conceal its absence. ‘I would rather fail with honour than succeed by cheating,’ wrote Sophocles. That ought to be a guiding principle in every profession, and the world would be a much better place if it was.

The talented Mr Hari didn’t live by it and probably doesn’t care. He’s done very well out of the world we have, and the tragedy - if that’s not too strong a word for his disturbing moral turpitude - is that too many other people never really cared either, as long as he made them money or told them what they wanted to hear.

May 14, 2024

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Future

Where would we be without the future? The ability to predict what lies ahead of us is one of the things that separates animals from humans. Unlike cats, say, we can set ourselves personal or societal future goals and use the future to measure our progress. We can also take action to prevent or prepare the negative futures we might imagine. In effect, the future provides us with a blank screen of unknowability onto which we project our hopes, expectations, and sometimes our worst fears.

In the wake of 9/11, military and security thinktanks in the US and Britain conducted war games and ‘future-planning scenarios’, many of which which used 9/11 as a narrative starting point to imagine the threats the future might contain. Today, defence departments draw up budget wish-lists to prepare for war with Russia, Iran, or China in five or ten years time.

The future also serves more benign purposes. Parks, hospitals, and protected natural spaces are all gifts to the future as well as the present. When a scientist spends years working on a cure for cancer, they don’t necessarily expect to see the results of their work in their own lifetime, but the knowledge that their research might help someone someday is enough motivation.

Similarly, when we honour soldiers who died for ‘our freedom’ or for ‘the nation’, we are praising them for sacrificing their lives for a world they knew they would not see. Some might think this kind of future-talk is a little grandiose. But millions of us live with it all the time. We want our children and grandchildren to have a future worth living in, and we hope that the world they inherit should be at least as good as the one we lived in, and hopefully, even better.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

But what happens when the future appears so terrible that no one would want to live to see it, let alone pass it on? To put it another way, how do we continue to live, individually, and collectively, faced with a future that everything we know tells us may be infinitely worse than the present? I pose these questions, in the light of last week’s Guardian questionnaire, which asked 380 climate scientists what they felt about the future. Their responses make grim, and if you think about too much, terrifying reading. 77 percent of respondents predicted that that global temperatures will reach at least 2.5C within a few decades. 42 percent thought that temperatures were more likely to be higher than 3C - the nightmare scenario that will make the planet unliveable for millions of people, most of whom live in the global South.

Only 6 percent of respondents believed that the current aspirational target of 1.5C would be reached. The world, in other words, is burning up, and humanity faces a catastrophic future that threatens life on earth, because of what humans have done. These predictions aren’t a novelty in themselves. As far back as in 1972, the Club of Rome’s ‘Limits to Growth’ report issued a pretty stark warning:

That our planet is physically limited, and that humanity cannot continue to use more physical resources and generate more emissions than nature is capable of supplying in a sustainable manner. In addition, it will not be possible to rely on technology alone to solve the problem as this would only delay reaching the carrying capacity of the planet by a few years…that it is possible, and even likely, that the human ecological footprint will overshoot the carrying capacity of the planet, further explaining that this would likely occur due to significant delays in global decision making while growth continued, bringing the human footprint into unsustainable territory.

In 1992, 1,700 leading international scientists, including a number of Nobel laureates, wrote an open ‘warning to humanity’ which argued that:

Human beings and the natural world are on a collision course. Human activities inflict harsh and often irreversible damage on the environment and on critical resources. If not checked, many of our current practices put at serious risk the future that we wish for human society and the plant and animal kingdoms, and may so alter the living world that it will be unable to sustain life in the manner that we know. Fundamental changes are urgent if we are to avoid the collision our present course will bring about.

Those fundamental changes haven’t taken place. Environmental conferences have come and gone. Targets have been set and missed. Agreements have made, broken, and then made again. Warnings have been issued and ignored. In 2019, 15,000 scientists called on governments to make serious and rapid changes to high-emitting economic systems or face ‘untold suffering’ worldwide. And last year another international team of scientists wrote in the journal Biosciences:

We are afraid of the uncharted territory that we have now entered. As scientists, we are increasingly being asked to tell the public the truth about the crises we face in simple and direct terms. The truth is that we are shocked by the ferocity of the extreme weather events in 2023.

Rising temperatures and record low levels of sea ice, the scientists argued, constituted further evidence that human activity was ‘pushing our planetary systems into dangerous instability’. As a result, an incredible 6 billion of the Earth’s almost 8 billion inhabitants could find themselves ‘in regions that are no longer habitable’.

Predictions like these point towards calamities that are difficult for the mind to comprehend, and they flit in and out of media and political discourse on a routine basis. But the novelty of the Guardian piece was the despair expressed by so many of its respondents:

The Age of FoolsFrom experts in the atmosphere and oceans, energy and agriculture, economics and politics, the mood of almost all those the Guardian heard from was grim. And the future many painted was harrowing: famines, mass migration, conflict. “I find it infuriating, distressing, overwhelming,” said one expert, who chose not to be named. “I’m relieved that I do not have children, knowing what the future holds,” said another.

One South African scientist predicted ‘a semi-dystopian future with substantial pain and suffering for the people of the global south. The world’s response to date is reprehensible – we live in an age of fools.’

I felt for these scientists, many of whom have spent their careers patiently accumulating the data to persuade governments and the public of the seriousness of what is happening, whilst also fending off cynical and well-funded attempts to undermine or discredit their findings, because who needs experts nowadays? It’s quite something when you read a scientist saying they would have been better off working as a night club singer, and another saying how relieved she was that she wasn’t having children.

I sometimes come across people - many of them far too young - expressing this kind of pessimism. But when you hear it from scientists who tend to rely on facts rather than emotion, you know - if you didn’t know it before - that you are in a very serious situation.

At least you would know it, if anyone reported it. But apart from the Guardian, no one did. The Radio 4 Today program presenters briefly mentioned the questionnaire, before chuckling at its ‘gloomy vibes’. No one else even got that far. Other matters were more pressing: the Gaza massacre; the Met Gala; Stormy Daniels and was Hazza snubbing the king?

Unbearable irresponsibility is the least of the charges you could aim at our shallow and puerile media, and the culture of endless distraction that it nurtures on a daily basis. But even if journalists, politicians, policymakers and the public choose to ignore it, climate breakdown will not go away - we are staring into a future that looks increasingly like a gun aimed at humanity’s head. And our collective failure to act on what we know is a bleak indictment of our species and also of the dominant global economic system - capitalism - that has driven the Anthropocene for the last two years, and brought the world to the brink of a disaster it may not be able to come back from.

My generation grew up living with the possibility that people twice our age might turn the world into a smoking nuclear ruin, inhabited by mutants and cockroaches. None of us felt that we had any control over this outcome. We weren’t the ones with the codes and our fingers on the ‘nuclear button.’ That was the grown ups - the ones who had to step to the plate each election and reassure the doubters that they weren’t lily-livered pinkos, and that they too would incinerate entire cities if push came to shove.

Such nobility of spirit, and there is still plenty of it.

That was the future then. Or at least we thought it might be. Millions of us marched to prevent it. In the end we learned to live with it, apart from the occasional moments - the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Cruise Missile deployments of the 1980s, Chernobyl - when the possibility of a nuclear war or a nuclear attack plunged us into a paroxysm of terror, or galvanised us into action once again. Mutual assured destruction did not happen - more by luck than design. But the bombs never went away. They’re still with us - like monsters in the basement, except that they now seem almost like domesticated pets compared to the terrifying futures that are hurtling towards us as a result of climate change.

Nuclear weapons were a very specific creation of the military-industrial complex and a state-system that had experienced two world wars, and then launched itself into another frozen conflict which had the potential to annihilate all life on earth.

But climate change is rooted in what all of us do: what we eat and consume; where and how we travel; the energy we use. It’s rooted in the everyday workings of societies that have believed for too long that nature is an inexhaustible resource, in a system recklessly pursuing endless growth on continual ‘growth’; in urban societies whose inhabitants have forgotten that they are not separate from nature, but part of it.

The pandemic briefly reminded us of this connection - almost - but that insight has too quickly been yawned away. And now we are contemplating the prospect of a 3C temperature rise after a series of record hot summers. How many heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, extinctions and dyings, storms, floods, and hurricanes does it take to make us realise that the climate crisis is the deadliest threat that humanity has ever faced?

The fact that we have allowed this to happen when we had the chance to take remedial action is a monumental moral and political failure. It makes our politics obscene, our arts pointless, and our species ridiculous. It is an unforgiveable dereliction of duty that so many politicians still insist on growth as a solution for every socioeconomic problem, regardless of its environmental consequences. We should be disgusted by the libertarian sociopaths, the billionaires and corporations that who burn rain forests, joke about wildfires, and global warming and species depletion into ‘anti-woke’ wedge issues and feeble-minded conspiracy theories about fifteen minute cities.

So it’s not at all surprising that scientists should now feel that their efforts have been pointless. But their despair should galvanise us to anger, and to action. We can’t allow the futures that were presented to us last week to numb us into a fatalistic resignation.

It may be - it is entirely conceivable - that humanity taken as a whole, will not be able to live up to its best hopes and its best members, and cannot unite to live up to the responsibilities that our accidental curatorship of this astonishing planet imposes on us. Humans aren’t gods. We might lose this earth. Maybe we aren’t worthy of it. But we don’t have to be spectators of our collective downfall. Do we really want to become what Elon Musk calls an ‘interplanetary species’, and seek our future on a planet that is as barren and desiccated as he is?

That really would be a future fit for an age of fools, and only fools would seek it. So we should acknowledge the despair of the scientists and concentrate our efforts on preventing the dire outcomes they predict. We must build the networks and movements that really can bring about ‘fundamental changes’, and reject the nihilistic politics that are leading us to disaster.

Alternatively, we can shrug our soldiers, and dismiss the climate scientists as agents of wokery or a globalist conspiracy to take away our ‘freedom.’ But that way madness lies. So we need to face the calamitous future that was presented to us last week, and take actWe must find a way to protect and heal this wounded planet on which our collective survival depends, and extend ties of solidarity to the people who are most at risk from our collective idiocy.

Of course we might fail. But doing nothing means that failure is guaranteed. Because the one certain thing about the future is that it hasn’t happened yet, and that means that there is still a chance - however faint - to avert, or at least prepare for what is coming.

May 7, 2024

Tin Soldiers and Biden Coming

There are moments in history when it suddenly becomes clear that the rules have changed, and you are now in entirely new territory. Last week, Professor Carolyn Fohlin, an Economics professor at Atlanta’s Emory University, was arrested on campus, because she had verbally questioned the rough treatment of one of her students who was being arrested for protesting the Gaza War.

Video footage of the incident clearly shows that Fohlin used no force or violence herself, but even though she was a woman in her sixties, she got the full treatment: one cop twisted her wrist and threw her down onto the road, and rammed his knee into her back while another forced her arms together and slipped on the plastic cuffs.

At no point did Professor Fohlin put up any resistance. Face down on the ground, she shouted to the police that she was a professor. She might as well have been Saint Theresa of Avila for all the impact her protestations had on these thuggish automatons, who clearly did not care who she was or who saw them.

This is what impunity looks like, and it’s generally safe to assume in politics, when you see police behaving like this towards non-violent protesters, that the cops aren’t representing the moral high ground. On the contrary, at Emory, as in so many US campuses, the police are representing both a government that has been actively complicit in the annihilation of the Gaza Strip, and university administrations that have also made it clear which side they’re on.

Over the last week, police engaged in the kind of semi-militarised law enforcement practices that have become routine in the US for many years. Rubber bullets, flash bang grenades, beatings, phalanxes of police in Darth Vader riot gear, even reported snipers - all these tactics all been deployed against peaceful protests and campus occupations in more than 30 US colleges.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Similar methods have been used in Germany, where successive governments have all but made pro-Palestinian protests illegal, to the point when even minors wearing the colours of the Palestinian flag have been arrested, and the slogan ‘from the river to the sea’ has been made a criminal offence. Here in the UK, the police have so far been fairly restrained, despite persistent calls from Suella Braverman and others rightwing ghouls for a crackdown on ‘hate marches’ that, once again, have been overwhelmingly peaceful.

To some extent, this type of heavy-handed policing is the logical extension of longstanding attempts to delegitimize and suppress the pro-Palestinian movement, which began before the Hamas pogrom/raid on 7 October last year. The criminalisation of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement in Germany in 2019 and Michael Gove’s 2023 anti-Israeli boycott bill were all part of this general trend.

But now these same governments have either colluded directly in the insane destruction that Israel is inflicting on Gaza, or quietly accepted it as some kind of war-is-hell tragic necessity. The consequences of such collusion and passivity have been unimaginably horrendous and impossible to ignore. So far Israel has killed 35,000 Palestinians and injured tens of thousands, and left much of the Gaza Strip in ruins. According to the UN, rebuilding Gaza will take at least 16 years and cost £32 billion.

Who will do that rebuilding, assuming Israel allows anyone to do it? Where will Gaza’s nearly two million people live while they wait for houses to live in? Who will feed them? What hospitals will be available to them? What schools will the children of Gaza go to? What kind of society can possibly take shape in such conditions? Who kind of lunatic believes that anyone, either Palestinians or Israelis, will find security in such circumstances, let alone that a ‘two-state solution’ can emerge from these ruins?

The answers to these questions have been drowned out into the void of retribution, militarism and strategic delirium that has turned the descendants of the refugees driven out of Palestine during the first Nakba, into the terrorized inhabitants of another tent city. Yet still Israel’s backers insist that Hamas will be defeated, and that if/when that happens, the despised Palestinian Authority or some equally improbable international force can waltz back into Gaza, with the grateful acquiescence of the people who have been bombed, starved, traumatised and shot to pieces, and there will be some kind of ‘peace process.’

So many powerful people and institutions have held onto these ideas, without questioning whether they are achievable, and only now are some of them beginning to realise how Netanyahu played them. And these hapless culprits aren’t the Trumps, Mileis, or Orban, or any of the far-right ‘populists’ who currently menace western democracies. If Gaza is a genocide, it’s a liberal, democratic genocide, facilitated by governments that claim to uphold human rights, and which have often used violations of these rights as a pretext for military ‘intervention.’

Unable or unwilling to change course, these governments have coupled weak condemnations of Israeli behaviour with military aid and diplomatic support, even as the ground shifts under their feet. Because the destruction that Israel has inflicted on Gaza is so staggering, pitiless and intense, that more and more people are horrified and disgusted by it.

The international eruption of campus protests is a sign of this. A new generation has embraced Gaza and the Palestinians as their cause, just as previous generations once adopted Vietnam and Apartheid. Initially, faced with this upsurge of solidarity, Zionists and their supporters smeared the participants with the usual labels. They were privileged, naive, violent, historically-ignorant, decadent, terrorist-supporters etc. Inevitably, they were antisemitic. In the UK, as in the US, pro-Palestinian protesters have been accused of threatening Jews, making Jews feel unsafe, dividing communities, promoting violence, and supporting Hamas.

Few of those who make these claims had anything to say when Zionist ‘counter-protesters’ attacked students in their tents last week, while the police did nothing. But the pace and intensity of these protests show that these old tricks are no longer working. Out of the rubble of Gaza, an international movement has been born which shows no sign of abating, and it is in these circumstances that the police baton has been deployed to suppress criticism of the governments and institutions that are defending the indefensible. This is why pro-Palestinian protests are being banned in Europe. It’s why the police phalanxes were present at American university campuses last week. Such deployments don’t occur by accident, any more than the police riots in Chicago in 1968 or the 1970 shooting of four students at Kent State University were accidents.

It’s less than four years since Biden’s Democratic Party called for a new America in a brilliant campaign video that evoked Civil Rights activism, and showed scenes of violent police repression under Trump, accompanied by the Black Eyed Peas son, ‘The Love’:

It was a powerful statement, but now the love has gone. And Biden last week said nothing about the brazen police violence at Emory, or the attacks at UCLA, but condemned ‘acts of chaos’ on US campuses, and supported police efforts to restore ‘order.’ And over here, Commons Leader Penny Mordaunt warned UK protesters that they also face a ‘strict response’ if they attempt to replicate the ‘disgusting’ protests in the US.

But the tents are spreading. On Friday they were outside Sheffield University, where I work. Now they’re in Belgium and the Netherlands. When a movement achieves such momentum, brute forces rarely stops it. There are signs that the West’s obtuse, cynical and cowardly enabling of Israel’s carte blanche in Gaza is already hurting some of the governments or political parties responsible. This is what happens when you defend the indefensible or actively facilitate it.

Right now, Israel may be ‘winning’ the war in Gaza as it begins its assault on Rafah, but it is draining political support in one country after another, and so are its enablers. Police batons and tear gas can clear campuses, but they can’t bring that support back. Nor can bad faith accusations of antisemitism. There are, of course, antisemitic elements at the fringes of the Palestine solidarity movement, that must be resisted and opposed. But these minority voices do not define a movement that represents the only hope, in the long-term, of dragging Israel towards some kind of sanity, just as the anti-Vietnam war movement once did with America itself, and anti-apartheid did with South Africa.

That prospect may seem remote right now, but is no more unrealistic than the fantasy that Gaza can be bombed into peace, or that the annihilation of Gazan society will make Israelis feel secure. Neil Young once sang of a generation that was finally on its own as a result of the Kent State shootings.

Last week, the protesters of Generation Z had their moment of clarity, when police batons gave American campuses just a faint taste of the repression that Palestinians in the Occupied Territories have known for fifty-seven years.

And instead of smearing them, we should applaud their bravery, principle, and resolution, because they really are the heart of this heartless world, and they have shown more genuine moral leadership than those who set the cops on them, and folded their arms while Gaza was obliterated.

April 30, 2024

What Have You Done Today?

Something like spring has arrived, breeding patriots as well as lilacs out of the dead land. Last week, ‘proud Englishmen’ were out in force on St George’s Day, telling us how much they love their country, whilst also questioning whether some people love it as much they do.

There was Rishi Sunak, fresh from his vicious speech promising to end ‘sicknote culture’, sitting in shirtsleeves at his desk with a St George’s mug and his usual sphinx-without-a-riddle smirk. But never mind, you skivers, Happy St George’s Day.

On the same day, Kier Starmer could be found writing in the Daily Telegraph that ‘Labour is now the true party of English patriotism’, and exhorting Labour candidates in the May elections to ‘fly the flag’ and mark St George’s Day ‘with enthusiasm’.

Thanks for reading Matt Carr’s Infernal Machine! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

These claims enraged the sword-carrying High Priestess of Albion, Penny Mordaunt, who told parliament that even though Labour ‘drape themselves in our flag’, the party was ‘packed with the same old socialists and a few new plastic patriots.’ Inevitably, the brutish opportunist Lee Anderson posted a video of himself pointing at his St George cufflinks, accompanied by a sarcastic ‘Trigger Warning’:

If you are a Guardian reading, advacado [sic] eating, Palestinian flag waving, Eddie Izzard supporting Vegan then this clip is probably not for your consumption. Happy St George's Day!

There wasn’t much happiness in this sour tweet, or in Anderson’s chest-thumping insistence that England has been a ‘gift to the world’ because it gave us ‘the Industrial Revolution. Culture, arts, music, sports’, and - of course! - ‘William Shakespeare.’

I find it difficult to imagine Anderson dropping in at the Tate or heading off to see Hamlet, or taking any interest in ‘culture, art, music’ except as fodder for pub-bore nationalist rabble-rousing, and he wasn’t the only one. In Whitehall and Trafalgar Square, crowds that included ‘far right groups and groups linked to football clubs’, as the Met put it, gathered to celebrate St George’s Day by drinking, brawling with police, and listening to speeches by the likes of Tommy Robinson and Lawrence Fox.

Afterwards, men and women waved flags and cans of lager, and cavorted amongst the lions in Trafalgar Square in a Hogarthian display of pageantry. Many of them included the ‘Big Englanders’, who JB Priestley once called ‘red-faced, staring, loud-voiced fellows, wanting to go and boss everybody about all over the world.’ Men in crusader outfits looking like extras from Monty Python condemned the ‘statue pullers’ who disrespected ‘our’ history and ‘our’ culture. MEGA (Make England Great Again) nostalgists listened to Richard Inman, the anti-Muslim founder of ‘Veterans Against Terrorism’, recalling when an ‘African prince’ asked Queen Victoria ‘What made England great?’, to which she supposedly answered by placing her hand on the Bible and told the prince, ‘This book made our nation great!’

Oh those good old days, when African princes could ask an English queen those questions, and get that answer. Now it’s all gone woke and Muslamic. ‘What has England ever done for the rest of the world?’ roared Inman, re-channelling the Life of Brian’s ’Romans’ speech? The answer:

We gave them democracy. We gave them law and order. We gave them peace. We fought against tyranny. We defeated Napoleon. We defeated the Kaiser. We defeated Adolf Hitler. We defeated the communists…We defeated the IRA

As Brecht might have said, didn’t we have one cook to help us do all that? But then you think of the ingratitude. To think that we did all these things only for an ungrateful world to treat us as if we were just anybody. Asked what it meant to be English, one woman memorably replied:

To be English is about walking through the street and being able to breathe, I think, to breathe. And when it is a sunny day, to be able to lie down, in our green pastures, as people would say.

That is a pretty low benchmark of Englishness. Elsewhere, a man with a Britain First badge said that St George had given us our ‘values’, and a woman complained to Times Radio that ‘We’re a coffee nation, not a tea nation anymore.’ A self-proclaimed ‘proud Englishman’ said that he ‘had enough of this country being taken away from us, from government more than anything, the elites, the globalists.’ Go figure.

And a haunted couple who looked as though they might have corpses buried under the patio declared: ‘We’ve come for our grandchildren because we don’t want them to grow up having to hide in a room, talking about how things used to be in this country. We want them to be as they were in our country.’

The interviewer didn’t ask which children were hiding in which room, because really, what’s the point?

It’s easy to mock this combination of victimhood, bluster, paranoia and stupidity. But we are all living in the country that people like this helped to create in 2016, many of whom remain pinned to the wheel of perpetual grievance and wounded national pride that pushed us into the Brexit fiasco.

I have never been able to comprehend this ‘proud Englishman/King and country’ patriotism - let alone the indignation that so often goes with it nowadays. There aspects of Englishness and the English that I can appreciate and even take pride in. The kindness of the nurses at Chesterfield Hospital; the English language; the anti-slavery campaign of Thomas Clarkson and his companions; The Detectorists - a warm and gentle take on weak masculinity and English eccentricity which manages to weave deadpan comedy and the Essex landscape into something surprisingly romantic and touching.

Portishead, Joy Division, John Cornford, Doctor Feelgood, Wilfred Owen, Waterloo Sunset, and the Bonzo Dog Doo Da Band are all expressions of Englishness, and I can say the same about EP Thompson, Zaiba Malik, Middlemarch, Rosie Holt, Steve McQueen and Linton Kwesi Johnson. I’m glad that William Blake could talk to angels in Lambeth and I would also like to see Jerusalem - the city of justice - in England’s green and pleasant land.

I also feel a certain national pride regarding that brief moment in 1940 when England was (with the help of the Empire - a contribution rarely acknowledged) the last democratic bastion against fascism, and SOE sent out its agents to work with the European anti-fascist resistance. I have a long list of English memories and associations : Dan Dare and the Mekon; Biggles and Commando comic; the Cambridge Folk Festivals which I used to go to as a teenager; the landscape of the Peak District where I live; Vaughn Williams; Snape Maltings; listening to sea shanties while eating fish and chips at Robin Hood Bay; Tess of the d’Urbervilles; Adrian Scott’s Sheffield poems; Steve Waters’ brilliant plays about East Anglia.

There’s a lot more where that came from. But none of this makes me think of England as ‘my’ country in any proprietary sense. It’s just the place where I was born and happen to have lived some years of my life. I don’t owe it my undying gratitude or loyalty. I’m not ashamed of being English, but I can’t even begin to think of myself as a ‘proud Englishman.’ I don’t find my ‘identity’ in this first person plural evoked by so many would-be culture warriors. I don’t think ‘our’ history is being erased if some slaveowner’s statue comes down - I see a bastard no longer receiving the honour he never deserved, in an era where the crimes of the past are no longer as easily concealed as they once were.

And as for those patriots who complain about ‘our culture’ being disrespected or under threat, don’t get me started. Culture is not fixed in time and place. Countries change and evolve, even if they don’t want to. Being English in the 21st century is not the same as it was when Alfred burnt the cakes, and it would be pretty alarming if it was.

So I have no desire to take ‘our country back’ (to where?) - except from the pseudo-patriots like Farage who have weaponised the most primitive nationalism and reactionary nostalgia and turned England into a grotesque parody of its worst features. I feel as estranged from this kind of patriot as they claim to be from the ‘statue pullers’, the ‘woke National Trust’, and all the other manufactured grievances that feed their endless victimhood.

How can I be proud of a country that supinely embraced the social cruelty of Thatcherism and austerity; that rode shotgun in the Iraq War; that is currently complicit in the Gaza genocide; that doesn’t even have the courage or the honesty to recognise or amend the mistake it made in 2016; that is now preparing to fly refugees off to Rwanda in defiance of humanity and logic, simply in order to scrape up some xenophobic racist votes; that made a depraved charlatan like Boris Johnson its prime minister?

Yes, I accept that Englishness is one layer of my ‘identity’, but there are other layers, as there are in all of us. And there other countries that I love, admire and care about, and whatever I was put on this earth for, it was not to love my country unconditionally and rally round its flag, simply because of an accident of birth.

Of course, this country is more familiar to me than any other, because I’ve lived longer here than anywhere else. But familiarity also makes me more painfully aware of the things that I can’t stand about it: its militarism; its arrogant, cruel, and clueless upper classes; its snobbery and inverted snobbery; its wretched deference; its unwillingness to challenge institutions that have long since passed their sell-by date and its unwillingness to stand up for institutions that deserve to be supported; its toleration of the harm inflicted on vulnerable people by successive Tory governments; its vile, toxic and mendacious rightwing press.

Each of us will have their own lists of pros and contras, just as the people of every other country will have theirs. To despise some things about this country doesn’t mean that I find it despicable. If English/British history isn’t the ludicrous fairy story told by the likes of Anderson and Inman, it isn’t a tale of unmitigated evil either. It has many traditions to draw on, and many ways of being English beyond the flags and crusader regalia, and displays of performative patriotism from people who claim to love their country as an abstraction, yet often seem remarkably indifferent to the people who live in it, in terms of their political choices.

I recognise that the current manifestation of these tendencies is the product of a particular historical moment: the upsurge in global ethnonationalism coupled with the still-weeping wound of Brexit that no politician dares even recognize, and the absence of any serious - or honest - national debate about how we got there and how we might get to a better place. In these circumstances, the ‘new’ patriotism is a renewed attempt to answer older questions which followed the end of Empire and the loss of what was once perceived as a world-historical ‘destiny’. At the end of his Beagle journal, Charles Darwin wrote of the future transformation of Australia into a ‘grand centre of civilisation’:

It is impossible for an Englishman to behold these distant colonies without a high pride and satisfaction. To hoist the British flag … seems to draw with it as a certain consequence, wealth, prosperity, and civilisation.

Darwin genuinely believed that the British flag was a force for good, and there are people who still believe that and cannot abandon the special place that goes with it, even if his juxtaposition of ‘Englishman’ with ‘British’ suggests a contradiction that we are still living with. Today, Britishness is no longer associated with greatness; its components are drifting away from each other. Faced with these ‘underdog’ Celtic nationalisms, the Englishness that was once subsumed into Britishness has reared its head once again, as a question to be answered and a problem to be solved.

Is it possible to construct an English identity that is not reactionary and backward-looking? Can ‘Englishness’ provide a unifying sense of belonging and identity that can heal a fractious society which has inflicted so many pointless wounds on itself? Will embracing some form of ‘inclusive’ Englishness - with the flag as its symbol - produce the active solidarity required to rebuild so much that has been broken and unite the population behind a common political project?

Much as I respect Gareth Southgate’s valiant attempts to shift the meaning of the St George flag, I don’t see it. Football is one thing: it’s another matter to persuade an entire nation to think differently - and honestly - about itself and its place in the world. That needs more than flags and pride, and maybe less of both. In his Telegraph article, Starmer wrote: