Gio Lodi's Blog, page 3

April 3, 2025

DMs Are Great. So Is Dinner.

On balancing digital connection with real-world presence.

In Eating alone in the age of connection, Gloria Mark reflects on the growing trend of people eating alone—or, rather, in the sole company of their smartphones.

The ritual of shared meals, long a touchstone of human connection, now competes with the distraction of screens. > The smartphone is the silent, omnipresent companion.

But, Gloria argues, this comes at the expense of our quality of life:

The tradition of commensality—sharing meals together—has long been revered across cultures. It is more than just a means of sustenance; > it’s a marker of community, a statement that life is richer when shared.

Sharing meals and drinks is a tradition that dates back many thousands of years. In A History of the World in 6 Glasses, Tom Standage traces the ritual of sharing a drink as far back as the third millennium AD.

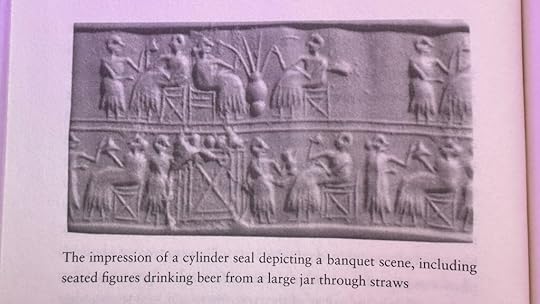

From the start, it seems that beer had an important function as a social drink. Sumerian depictions of beer from the third millennium BCE generally show two people drinking through straws from a shared vessel. By the Sumerian period, however, it was possible to filter the grains, chaff, and other debris from beer, and the advent of pottery meant it could just as easily have been served in individual cups. That beer drinkers are, nonetheless, so widely depicted using straws suggests that it was a ritual that persisted even when straws were no longer necessary.

The most likely explanation for this preference is that, unlike food, beverages can genuinely be shared. When several people drink beer from the same vessel, they are all consuming the same liquid; when cutting up a piece of meat, in contrast, some parts are usually deemed to be more desirable than others. As a result, sharing a drink with someone is a universal symbol of hospitality and friendship.

“The impression of a cylinder seal depicting a banquet scene, including seated figures drinking beer from a large jar through straws”, from A History of the World in 6 Glasses.

“The impression of a cylinder seal depicting a banquet scene, including seated figures drinking beer from a large jar through straws”, from A History of the World in 6 Glasses.As our working environments become increasingly remote and distributed, it can be tempting to focus on online relationships, especially for introverts. After all, it’s more likely to find job opportunities and people with similar interests online.

The new online relationships can be deep, useful, and satisfying, but in growing them we shouldn’t neglect the offline relationships that ground us. We still need real, in-person connections.

And it’s the same technology that some attack as the culprit for the erosion of in-person connections that creates the opportunity to spend more time together. Take remote work, for example. If a company operates in a truly distributed way, employees have plenty of flexibility for coffee or lunch dates with friends

And while most job opportunities are likely to come from your online network, there’s much more that can come from nourishing offline relationships with people you can actually share a space with. Which is why, by the way, remote companies invest in bringing distributed teams together in the same location throughout the year.

Looking into a smartphone during a meal can keep you connected to faraway friends—which is wonderful, as long as it doesn’t disconnect you from those right in front of you. It’s all about finding the ratio that works for you.

When we use our time and devices intentionally, we can build strong online networks and deepen real-world bonds.

March 31, 2025

Garmin’s Social Badges Fumble

Sport watches are for training, not posting.

Long-time readers know I love my Garmin watch. I configured it with no notifications or connected features. I use it to tell the time, as an alarm that wakes me up but not my wife, and, of course, as a training guide.

I’m also a sucker for the gamified badges system. Intellectually, I know those badges are vacuous and inconsequential. But what can I say? Whatever personality trait makes kids want to complete the Pokédex and grown-ups collect badges—I must have it.

But despite my irrational drive to catch ’em all, there are two badges I will not be trying to get.

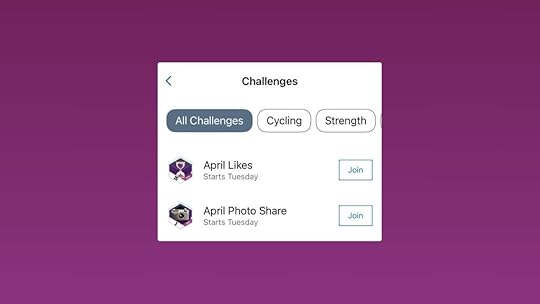

In April, Garmin users can win the April Likes badge by getting a total of 25 likes on their public activities and the April Photo Share badge by posting 3 pictures.

I appreciate Garmin shaking up their monthly challenges with something other than “run 5km this weekend, ride 40km the next, swim 1km the one after that,” but I have zero interest in fishing for likes.

If documenting your run with pictures and mile-by-mile breakdowns on Strava is your jam, then go for it. I actually enjoy reading the detailed breakdowns some of my friends post.

But for me, sharing workouts would dilute their value. It would add a status-seeking component to something I try to see as intrinsically valuable.

This goes back to one common topic on this blog: using technology with intention.

Whether it’s Garmin and Strava, Facebook and X, or LinkedIn and Substack, these are all tools that we should be able to use to our advantage. Opt-in to new features by decision, not by default.

I train for physical and mental health, not to share on socials. As such, I don’t share my workouts and I have no interest in the new Garmin social badges.

What about you? Do you exercise at all? If so, how?

Do you share your training on Garmin or Strava, or am I misjudging the extent to which people who exercise filter the experience through apps?

Keen to hear from you.

March 28, 2025

The Deutschian Dead End Is Wide Open

There is no dead end at the beginning of infinity.

When I came across The Deutschian Dead End via Increments Podcast, I was intrigued. Critical rationalism and the work of David Deutsch are all about error correction. For someone to identify and correct errors in those theories would certainly represent an advancement in our understanding of how to foster the creation of new knowledge.

Alas, I found none of that in the essay.

I intended to write a step-by-step critique, but after listening to Vaden’s pushback on Increments and Brett Hall’s commentary, I don’t think that’s necessary.

But here’s something I want to add. A great part of the essay criticizes the behavior of a group of people Kasra, the author, refers to as “critical rationalists”. I haven’t had much exposure with this community, but from the way Kasra describes it I get the impression it is a mostly online group of folks that seem more interested in dunking on socials than in making progress.

That, to me, has little to do with the work of Popper and Deutsch.

If someone reads Conjecture and Refutation or The Beginning of Infinity and comes out of it thinking that Popper and Deutsch are authorities to be followed, they completely missed the point! The problem lies with the readers, not the authors.

Granted, an author might intentionally develop a theory prone to such misinterpretations, but that’s not the case.

David Deutsch and Karl Popper are anti-authority to the core.

David often refuses to give advice in interviews because he does not consider himself in a position to tell the listeners what to do. And Popper, in his Epistemology and the Problem of Peace lecture, warned the audience:

But I would also ask you not to believe anything that I suggest! Please do not believe a word! I know that that is asking too much, as I will speak only the truth, as well as I can. But I warn you: I know nothing, or almost nothing. We all know nothing or almost nothing. I conjecture that that is a basic fact of life. We know nothing, we can only conjecture: we guess.

One does not need to “follow” Deutsch or “believe” in Popper. They work in the realm of ideas, not ideologies.

That Kasra missed the crucial distinction between the ideas themselves and how some readers misinterpreted them puts the entire essay on shaky grounds. It seems more a vent than an effort to provide a critique.

As far as I’m convinced, David Deutsch’s work is no dead end. It remains the beginning of what could be infinity, waiting for someone to genuinely improve upon it.

March 27, 2025

Why is there an octopus on the cover of Antifragile?

Mischievous author confuses designers.

The covers in one of the paperback reprints of Nassim Taleb’s Incerto series have neat designs featuring animals connected to the books.

Fooled by Randomness has a black cat, for superstition.The Black Swan obviously has a black swan.The Bed of Procrustes has an owl, for wisdom.Antifragile has an octopus, for… ?!Why is there an octopus on the cover of Antifragile?

Reddit user ‘NotTheAnts’ had a compelling conjecture:

Presumably because octopuses can regrow severed limbs…but doesn’t that make them robust, rather than antifragile?

If so, pretty ironic that the publishers committed the ontological error that the book chiefly warns against. Willing to be corrected though, maybe I’m missing something.

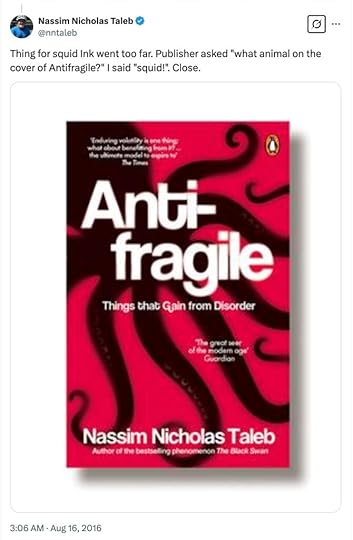

But the reason has more to do with Taleb being a character than the cover designers confusing—like many others do—robustness with antifragility.

Apparently, Taleb is a big fan of squid ink pasta and when the publisher asked for input on the cover, he replied “squid.”

Screenshot

ScreenshotSo there you have it: Antifragile features an octopus because its author enjoys eating squid ink.

I guess when your book goes through as many reprints as Taleb’s has, you can afford to sneak in a nod to your favorite food on the cover.

He really loves squid ink pasta…

March 24, 2025

Pay it forward without measuring it

Advice that resonates.

Here’s a bit of advice from Naval Ravikant that resonates with me.

Figure out what you’re good at, and start helping other people with it. Give it away. Pay it forward. Karma works because people are consistent. On a long enough timescale, you will attract what you project. But don’t measure—your patience will run out if you count.

The Almanack of Naval Ravikant

Notice the “long enough timescale” part. I like Naval because he explains things in a simple way without pretending they are easy.

We should be mindful of survivor and selection bias when listening to advice from successful people. What worked for them at a specific time might not work for us today.

I might be falling prey to biases as well, but I trust in Naval’s advice because it mirrors my experience with mokacoding.com.

I started writing on mokacoding.com because I was interested in software testing and wanted to get better at it. I was “good” at it and started “helping people” with how-to articles that I wrote as learning exercises. I gave them away for free on the blog and on Twitter. I kept at it consistently because there was so much for me to keep exploring. I also got lucky with the occasional retweet by respected folks—”attract what you project.” Eventually, that work led to a very modest book deal, a few invitations to teach workshops, a few more job opportunities, and, more importantly, made some great connections in the iOS community.

The time scale is the scary and frustrating part. Naval says “over a long enough timescale” and warns “your patience will run out if you count.”

This is why you should be writing—or sharing in whichever medium you prefer—to learn, first of all. If you write to become successful, and you don’t have the benefit of an existing platform, you’ll run out of patience. But if you write to share what you learn, to clarify your thinking, to solve problems, then you’ll go on forever, because you won just by writing the post. Anything else is a bonus.

Footnote: The quote comes from The Almanack of Naval Ravikant. I searched for the podcast in the Ferriss archives but could not find it. However, the book

March 21, 2025

The Appistocracy – A reaction

Customers are not subjects!

Kai Branch from Dense Discovery has some of the most thought provoking and thoughtful editorials online. Most of the time, I agree with the spirit but disagree with the details.

In Issue 329, Kai comments on The Appistocracy Inaugurates Trump by Ken Klippenstein. The post suggests there is “a new breed of elite,” so powerful and influential that “even megalomaniac Trump feels compelled to pay homage.”

The post refers in particular to Elon Musk (X), Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook/Instagram), Tim Cook (Apple), Sundar Pichai (Google), and Shou Zi Chew (TikTok), who were all present at the presidential inauguration.

Image sourced from Ken’s post.Misunderstanding technology

Image sourced from Ken’s post.Misunderstanding technologyKen writes:

Oligarchs are nothing new, but these six men have a power over us that is more intimate than other billionaires. They collectively build, run, and control what can only be likened to an appendage of our own human bodies, a new organ that most can’t imagine losing or losing access to.

I call them the Appistocracy.

The appendage of our own human bodies consists in the abstract conglomerate of smartphones, social media, and web-enabled services.

This is the first over simplification. All technology is an appendage to our bodies.

Ever since we learned to cook, we’ve been delegating part of our digestion to fire. We augment our skin with clothes that protect us from the freezing cold or scorching heat. Bicycles, cars, and other means of transportation are also appendages that allow us to cover large distances with little effort.

Smartphones and the internet are only the latest augmentation that enables our puny bodies to achieve more in the world. To paint them as “a new organ that most can’t imagine losing or losing access to,” is to simply observe our relationship with technology. It’s an unnecessary hyperbole. I bet you can’t imagine losing access to cooking, clothes, and transportation, either. Anyway, back to the article.

Misunderstanding impactThe first critique Ken makes of tech CEOs is that he believes the products they sell have negative effects on consumers.

The sociologists, anthropologists and psychologists are only just beginning to ponder the effects. Since the advent of the smartphone around 2012 or so, adolescent loneliness has skyrocketed, studies show.

This is a valid point and one that should not be overlooked.

However, like Vaden and Ben observed in their critique of The Anxious Generation—see latest Monday Dispatch— we ought to be very careful in adopting simplistic explanations that are based on correlation and observational studies. As Carl Sagan put it, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” and, we should add, an extraordinarily good explanation.

Another criticism in the article is that the Appistocracy runs companies that do nothing to improve society.

The robber barons of yesteryear, the Carnegies, the Fords and so on, at least employed a lot of people. At least they manufactured something tangible and of use to people’s lives. The Appistocracy doesn’t do anything to improve health care, housing, or education. Their contribution to infrastructure amounts to building more energy facilities to power their data centers and fuel their artificial intelligence empires.

This is an overly simplified picture. And the premise on employing a lot of people is plain wrong.

Ken brings up Henry Ford, possibly the single largest industrial employer in the 1920s. In 1929, he had 174,126 people on the payroll. Amazon reports 1 million jobs “directly created in the US. Adjusting for total US population, Ford employed 0.14% of the US population. Meanwhile, Amazon employs 0.3% of the current US population. So, barring inaccuracies in my sources, it’s safe to say that Amazon alone employs twice as many people in proportion to the US population as Ford did. How’s that for impact?

But let’s leave aside the gross misunderstanding on employees and think in terms of second order effects. These companies enable a whole substrate of careers that were not possible before.

From edgy YouTube commentators to shallow Instagram influencers, from the manufacturers of iPhone cases to the advertisers that work with Facebook, so many people are earning a living on top of the so called Appistocracy.

I’d argue those jobs are way more empowering—people actually have ownership and get to be creative. Unlike, say, tightening bolts on a Ford assembly line or shoveling coal for Carnegie.

As for infrastructure, health, and education improvements, both the unprecedented number of people directly employed by and those that earn in the Appistocracy’s ecosystem, pay taxes. It’s up to the government to spend that money wisely to improve services and infrastructure. As a matter of fact, the contribution the Carnegies, Fords, and Rockefellers of the early 20th century made to society in terms of health and education came mostly from their private philanthropy, not directly from their companies.

You could say I’m being too charitable. After all, it’s the internet that powers this new economy. It’s possible that Meta and YouTube, with their walled gardens, could actually be stealing revenue from creators.

The point I’m trying to make is not in defense of tech companies, but in defense of sound reasoning. If we want to identify and correct errors in the current system, then the critique we brought forward need to be sharp and accurate.

Misunderstanding usersThe jury might still be out on whether the overall contribution that Meta, Google, and the other big tech companies brought to society is net positive. But here’s something where there is no wiggle room: Ken denies users’ agency and in doing so demeans the readers.

Like jealous gods, these apps demand constant sacrifices: of our time, our attention, even our relationships.

Whenever I read sentences like those I am offended.

The implication is that most people—we the readers, users, and customers—are dumb targets, easily manipulated idiots. I feel treated like a mindless consumer with no choice or agency in how I interact with the digital world.

But no one forces you to open Instagram or to buy from Amazon. There is no law that requires posting on Facebook or sharing on TikTok. You can search the web without using Google or text your friends without using an iPhone.

We all have agency. Blaming the algorithms is a cheap excuse, a simplistic way to explain the complex state of our culture.

Apps might demand attention but they have no way to take it. They might try hard with their many shady tactics to keep us scrolling, but the quit button is always within reach.

Unlike the aristocracy of the past who was often in charge by force and inheritance and perpetrated a rigged system, Ken’s Appistocracy is “powerful” because people bought their products and used their services.

Most people buy iPhones because they are better and cooler than the competition. They use Amazon because it’s cheap, fast, and reliable. They watch YouTube because it’s more entertaining and personalized than television.

Ken himself is complicit in empowering the Appistocracy. His critique would land much more strongly if it came from a self-hosted site, distributed with an old-fashion newsletter provider and RSS feed. Instead, he posts on the platforms owned by the villains of his story.

If Ken is so concerned with the Appistocracy, I suggest he start by opting out from their services and find new ways to reach his audience. Then, he could make a compelling case for other people to do the same and start the chain reaction that will erode the influence these tech entrepreneurs have. If this sounds hard to do, it’s because it is. But as they say, “it’s not a principle if it doesn’t cost you something.”

For example, Kai hosts Dense Discovery with Krystal, a family-owned B Corp, running on 100% renewables, giving back 1% for the planet. He puts his money where his mouth is, and I respect him for that.

I have so much more to comment on this article: on the inevitability of wealth inequality, the difference between true oligarchs and entrepreneurs, on how one can’t help but wonder how much of this focus on billionaires is motivated by envy rather than concern, on the difference between CEOs and the companies they run, and how it was not Trump who paid homage but the other way around, but I’ll stop here.

I’ll leave you with Kai’s constructive conclusion:

Yet even as these digital dependencies deepen, so too does our capacity to question them – to carve out spaces of genuine presence in a world increasingly defined by algorithmic engagement.

As I said, Kai and I agree on the big picture even though the details vary.

The Appistocracy, to the extent to which it exists, may have influence over politicians but has no real power over our attention. We can always opt-out.

March 17, 2025

One note. 17,000 subscribers.

A “right place, right time” story a decade in the making.

On March 2nd 2025, Will Parker Anderson posted his first note on Substack. He had exactly two subscribers. Two weeks later, Will’s subscribers count was over 17,000.

How is this possible?! What’s his secret?

The secret is that there is no secret!

The note was nothing special: “Hey friends, I’m a senior editor at Penguin Random House. New to substack, but I’ll be posting tips about writing and publishing here weekly. Excited to connect with you all.”

Will’s massive growth came down to being the right person, in the right place, at the right time. Simple, not easy.

The right person: Senior editor at big publishing company giving writing advice.In the right place: Substack is a platform for writers. Maybe not every subscriber has a newsletter or aspires to publish, but it’s safe to assume a large enough portion are interested enough to subscribe.At the right time: On March 12, Substack announced having crossed 5 million paid subscriptions, just four months after having reached 4 million.Sure, there might have been a lot of luck in there, too. For whatever reason, his note might have tickled the Substack algorithm in just the right way to reach escape velocity and go viral.

But that only explains the “right time” factor.

There’s an apocryphal story about an elderly Picasso being approached in a restaurant by a diner who asked for a sketch on a napkin. The master took the napkin and in just a few strokes produced a portrait in his unmistakable style. “That will be 50,000 francs, madame.” “How is it possible,” exclaimed the woman, “it took you no more than thirty seconds!” “No,” replied Picasso as he folded the napkin and put it into his pocket, “it has taken me forty years to do that.”

Becoming a senior editor at one of the world’s top publishing houses takes years of effort. And if you check Will’s LinkedIn, you’ll indeed see that he’s been in the business since 2013.

So, well done Will. I am one of the many subscribers and am looking forward to your advice.

March 14, 2025

Problems are inevitable. Problems are soluble.

Get to work.

Of all the ideas in David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity, “problems are inevitable; problems are soluble” stood out to me from the very first reading. It’s an observation on reality, a warning to stay vigilant, and a challenge to be bold and take action. Like all great wisdom, it’s simple to understand, yet the more you reflect on it the more depth you discover.

Problems are inevitable

Problems are inevitableFrom the book:

Problems are inevitable. We shall always be faced with the problem of how to plan for an unknowable future. We shall never be able to afford to sit back and hope for the best. Even if our civilization moves out into space in order to hedge its bets, as Rees and Hawking both rightly advise, a gamma-ray burst in our galactic vicinity would still wipe us all out. > Such an event is thousands of times rarer than an asteroid collision, but when it does finally happen we shall have no defence against it without a great deal more scientific knowledge and an enormous increase in our wealth.

And later on:

In addition to threats, there will always be problems in the benign sense of the word: errors, gaps, inconsistencies and inadequacies in our knowledge that we wish to solve – including, not least, moral knowledge: > knowledge about what to want, what to strive for.

Maybe I’m just lucky that most of my problems are first world problems — challenges instead of threats — but I find that framing gives license to focus entirely on solutions. There’s something reassuring about how David explains problems as an inevitable part of life. Maybe I’m just lucky that most of mine are first-world problems—challenges rather than threats—but that framing helps me to focus entirely on solutions.

When something is inevitable, all energy spent complaining about it is wasted. Take that option away, and all that’s left is to get serious and start working on it.

Understanding that problems are inevitable also puts them into perspective. Because when a problem is solved, a new problem arises:

A solution may be problem-free for a period, and in a parochial application, but there is no way of identifying in advance which problems will have such a solution. Hence there is no way, short of stasis, to avoid unforeseen problems arising from new solutions. > But stasis is itself unsustainable, as witness every static society in history.

Problems are inevitable. The best you can hope for is to move toward ones that are more interesting to solve.

Problems are solubleAgain from The Beginning of Infinity:

Since the human ability to transform nature is limited only by the laws of physics, none of the endless stream of problems will ever constitute an impassable barrier. So a complementary and equally important truth about people and the physical world is that problems are soluble. > By ‘soluble’ I mean that the right knowledge would solve them.

If recognizing that problems are inevitable is the spark to start searching for solutions, then knowing they are soluble is the fuel that keeps the search alive.

If the laws of physics permit it, it’s possible. The challenge is figuring out how, generating the wealth to make it real, or both.

The YouTube channel Kurzgesagt – In a nutshell has many videos exploring ideas that are theoretically possible but out of reach because we haven’t yet solved the technological problems to build them. Space elevators, Dyson swarms, Mars terraforming, and skyhooks , to name just a few.

David adds an important caveat: problems can be solved, but they won’t solve themselves.

It is not, of course, that we can possess knowledge just by wishing for it; but it is in principle accessible to us.

Also:

That problems are soluble does not mean that we already know their solutions, or can generate them to order. > That would be akin to creationism.

With “problems are inevitable; problems are soluble,” David sums up some things all doers intuitively understand: Everything is figureoutable. Complaining and protesting are wasted effort. The only productive thing to do is to roll up your sleeves and get to work.

March 12, 2025

Work Like Mycroft Holmes

Be unique and indispensable.

Here’s how Sherlock Holmes describes his brother Mycroft to the trusted Dr. Watson:

[Holmes] “You would also be right in a sense if you said that occasionally he is the British government.”

[Watson] “My dear Holmes!”

“I thought I might surprise you. Mycroft draws four hundred and fifty pounds a year, remains a subordinate, has no ambitions of any kind, will receive neither honour nor title, but remains the most indispensable man in the country.”

“But how?”

“Well, his position is unique. He has made it for himself. There has never been anything like it before, nor will be again.

The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Notice the last paragraph. Mycroft’s position is unique. He has made it for himself. There never was and never will be anything like it.

Admittedly, Sherlock Holmes and his brother Mycroft are works of fiction, figments of Sir Conan Doyle great imagination. We cannot draw real life lessons from them, but nothing stops us from being inspired.

When reading about Mycroft, I was reminded of Kevin Kelly in Excellent Advice for Living:

Don’t be the best. Be the only.

On the same wavelength was Naval Ravikant post on X:

Become the best in the world at what you do. Keep redefining what you do until this is true.

Being the only, creating a unique position for yourself, is what I think of when describing the synergist engineer, someone with deep knowledge and in curated number of subjects, which they combine to offer one original and valuable service.

Be careful not to gloss over the “valuable service” part of the recipe. When thinking about being the only, at least in the context of work, what you offer has to be valuable. That is, people have to be willing to pay for it.

Your personal combination of interests and skills already makes you unique, but it might not necessarily make you valuable in the marketplace. Then again, many people have turned unique hobbies into businesses and now make a living on YouTube or by selling online.

Technology and progress expand the ways people can earn a living. This is the best time to take inspiration from the Holmes brothers and create a unique position for ourselves.

If you need more inspiration from Sherlock Holmes, see The Sherlock Holmes Information Diet.

The inspiration for this post came from listening to the Sherlock Holmes Short Stories podcast narrated by Hugh Bonneville. It’s a well produced podcast, on par with any audiobook, and lovely combo for a Sherlock Holmes and Downtown Abbey fan such as myself.

March 10, 2025

Provide. Protect. Project.

The roles of a family man.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash.My 8-year-old son and I were talking about the roles of a man in the house.

We thought of three important roles, and since we like to play around with words, we looked for a nice alliteration.

Provide: A man should work hard and work smart to provide for his family.Protect: A man should protect his family. This covers a wide spectrum of activities, from being fit and capable of defending the family from direct harm, to ensuring the home is safe and well-maintained, with nothing at risk of breaking.Project: A man should show, not tell. Transmitting values starts with living up to them. Only then can come discussions and explanations.Granted, there’s more to being a man and a father than providing, protecting, and projecting. But I find it’s useful to have these little catchy reminders. I see them as handles you can use to grab a hold of a nuanced topic and lift it into your mind.

Besides, having that conversation with my son was more important than identifying a precise model. It showed him — I hope — that I take him seriously, that I strive to improve, and that he can too.

It was also a good excuse to talk about something other than LEGO Ninjago or the latest fart jokes.