Gio Lodi's Blog, page 2

August 21, 2025

Reject Performative Busyness

We live in exciting times. Gone are the days of hunting, gathering, and struggling for survival. Thanks to technology, many of us earn a living by applying our creativity toward solving problems we find interesting. And as we keep innovating and creating, more problems arise and more people have a chance to find their problem-market fit.

Yet despite all the new tools and possibilities, many knowledge organizations stagnate. So much potential remains untapped.

One culprit is a pervasive culture of performative busyness: using visible activity as a proxy for productive work1.

A lot of time at work is spent doing theater.

Communication Theater. Being always online and replying to messages and emails as soon as they are received to signal presence.

Meeting Theater. Daily stand-ups and other ritualistic meetings where people take turns talking about the work they plan to do instead of actually doing the work.

Reporting Theater. Status updates and progress reports rich in detail, screenshots, and graphs that take as long to compile as the work they describe.

Task Theater. Bloated project management software with hyper-granular, multi-dimensional, interconnected tickets to curate like gardeners.

Cultural Theater. Joining every culture event and strategically interacting on highly visible projects to show engagement and alignment.

None of these activities are inherently bad or completely wasteful. Teams need a way to track work in progress and spread workload, internal seminars are great learning opportunities, and asynchronous communication channels ought to be monitored. These tasks often look and feel like “real” work, but notice the difference in customer-facing progress between a day spent pruning the backlog and one spent writing code2.

For a knowledge organization to operate at its full potential, we need to minimize performative busyness in favor of actual problem solving.

Cal Newport* has a proposal to move in this direction: Let your best people cook.

Cal starts from a Brandon Sanderson interview where the prolific author described how his company is organized around the principle “let Brandon cook.” Creating stories is the most valuable thing Sanderson can do for his business, so the whole organization is optimized for it.

Most knowledge organizations have their own Brandon Sandersons: people with high-return creative skills. When these people apply their craft, they disproportionately bring the product forward. It’s in a business’s best interest to let its high-impact people apply their skills for as long and with as few distractions as possible.

Obviously, not everyone in a company has a role that directly and disproportionately advances the product. But it seems reasonable to expect that, as we optimize for real-world progress (shipping) over performative busyness, the workflow changes involved will also benefit those with supporting roles. Alternatively, a knowledge organization with a more focused creative workforce might need far fewer auxiliary roles, and the people in those roles will have more ownership and opportunities to use their creativity.

There are so many problems waiting to be solved and we have never been in a better position to take them on. It’s truly tragic to think how much progress we are forfeiting because we’re projecting busyness instead of actually applying our creativity.

As Cal urges, “let the Brandon Sandersons of your company cook!”

1The notion of performative busyness is a redressing of what Cal Newport calls pseudo-productivity in his 2024 Slow Productivity book, defined as “the use of visible activity as the primary means of approximating actual productive effort.” The concept of using “busyness as a proxy for productivity” from Cal’s 2016 seminal book Deep Work was also influential. Still, I find the “performative” in performative busyness better conveys how far removed from genuinely productive work those activities are.

2Some nuance is required. I’ll admit that the comparison is not always favorable to coding. A day spent identifying the most useful projects to work on could set the direction for a very productive work cycle. Conversely, a day of aimless coding might build unnecessary functionality or, worse, introduce dangerous bugs. But given a project already identified as worthy and a developer who knows what they’re doing, I’ll always bet on actually doing the coding as the surest way to make progress.

August 19, 2025

Different Flavors of Problems

According to Karl Popper, problems are the starting point for progress. All life is problem-solving. What differentiates humans from other known life forms is in how we solve our problems: through conjecture and criticism.

But what counts as a problem?

Your house being on fire is a problem. Whether to have Italian or Indian for dinner is also a problem. Obviously, the two differ greatly in magnitude.

A house on fire is a risk-of-ruin kind of problem. What to have for dinner is a first world problem.

When thinking about problem solving and knowledge creation, I find it useful to categorize problems based on the consequences of failing to solve them.

Here’s a tentative taxonomy:

Threats

Challenges

Puzzles

Choices

Trivialities

On one end, we have threats. These are problems that, if not solved, will have catastrophic consequences.

After threats we have challenges. Solving these problems brings an improvement, but, unlike threats, failing to solve them won’t be devastating. Examples of challenges include learning new skills, getting a promotion, and improving as an athlete.

Next, we have puzzles. These are gaps in one’s understanding, the “that’s funny” moments when reality doesn’t match your expectations and you want to know why. For a scientist, this could be the need to explain experimental results that don’t match the most advanced theory.

Choices are problems with more than one possible solution. The task is to find the best solution in context or create an entirely new and better one.

Finally, we have trivialities. A fly buzzing around your desk, cold coffee in your mug, a flat phone battery, these are examples of trivial problems with inconsequential solutions.

The categorization is somewhat subjective. The problem of the buzzing fly might be trivial for me, with my noise-canceling headphones, but far more serious for someone taking an exam who is distracted by the noise.

Of course, classifying problems this way does little in the way of solving them.

But my hope is that a richer vocabulary can be a helpful tool for prioritization and introducing novices to problem-solving via conjecture and criticism.

August 18, 2025

When More Inputs Is What You Need

Welcome to Monday Dispatch, a bonus edition for paid subscribers. Thank you for your support—it means a lot and helps me keep writing.

This week, a personal story on being stuck consuming without creating, and finding a way out by… consuming more?!

I had a mental stew on the stove, but it needed extra flavor.

I had a mental stew on the stove, but it needed extra flavor.The past few weeks have been frustrating.

I had that rare kind of time off when the kids are at school. In the lead-up to it, I dreamed of getting so much done. Live like someone with the luxury of working without having to work. Write, read, code, train.

But when the time came, I couldn’t get started on anything. All those shiny ideas had lost their sparkle. Absolutely no gumption.

August 15, 2025

Software Estimates Are BS

Note for non-developers: This post deals with details of software development, but the underlying ideas apply to any creative work that involves communicating timelines and dealing with uncertainty. If you work in a different field, I’d love to hear about what estimate analogues or alternatives you use.

Common wisdom has it that developers suck at estimating. But the reason estimates are hard has little to do with coders. It’s rooted in the creative nature of software development.

Writing software is a process of problem solving. Solving a problem requires knowledge creation through conjecture and criticism, trial and error.

As Karl Popper and David Deutsch taught us, we cannot predict the content of future knowledge. If we could, then we would already possess that knowledge.

In the same way, we cannot predict how long it would take to create new knowledge. If we did, we’d already know how to create it.

Asking a programmer how long it will take to build something is akin to asking a researcher how long it will take to discover a new scientific theory. It’s something that cannot be answered with confidence.

Granted, there are projects where the problem to solve is not novel and devs can give a relatively accurate ETA. For example, in my day job as a mobile infrastructure engineer, I have set up continuous integration for so many new apps that by now I can tell with some confidence, “I’ll do it within a day.”

But even then, there are always surprises: a vendor update or an API change may require tooling adjustments, and you won’t know how long that takes until you’ve done it.

So, overall, estimates are bullshit.

They are no more than prophecies. They’re stage props we use to pretend software teams can run like assembly lines.

But an “it’ll be ready when it’s ready” attitude won’t get you far in business. There are, after all, real world constraints of budget, window of opportunity, and clients’ patience. We still need ways to coordinate over timeframes. Besides, teams and individuals need structure and accountability.

Here are two approaches that account for the unpredictable nature of knowledge creation without giving up on a structured schedule.

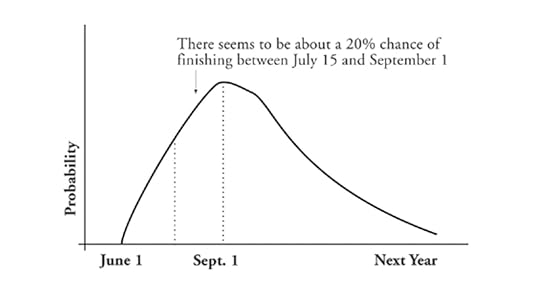

Probabilities, Not EstimatesIn his book Slack: Getting Past Burnout, Busywork, and the Myth of Total Efficiency, Tom DeMarco advocates acknowledging uncertainty and being upfront about risks.

He proposes using risk diagrams to model estimated time of project completion.

This risk diagram is an explicit declaration of uncertainty. It shows the relative likelihood that completion will happen at any given time. The area under the graph between any two dates represents the likelihood that the project will complete during that period.

I like this approach because it’s more intellectually honest and accurate than producing a single value. It also helps other parties involved with the project to plan for different scenarios.

Fixed Deadlines, Flexible ScopeAnother approach I really like is the one championed by 37signals, where teams work in cycles with fixed duration but variable scope.

As founders Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson describe in It Doesn’t Have To Be Crazy At Work:

Another way to think about our deadlines is that they’re based on budgets, not estimates. We’re not fans of estimates because, let’s face it, humans suck at estimating. If we tell a team that they have six weeks to build a great calendar feature in Basecamp, they’re much more likely to produce lovely work than if we ask them how long it’ll take to build this specific calendar feature, and then break their weekends and backs to make it so.

A deadline with a flexible scope invites pushback, compromises, and tradeoffs—all ingredients in healthy, calm projects. It’s when you try to fix both scope and time that you have a recipe for dread, overwork, and exhaustion.

Earlier, I compared software development with science research because both endeavors require creative problem solving. But developers have the advantage that software is malleable and iterative. You can’t iterate your way to the successor of General Relativity. It’s either done or it isn’t. But you can solve the problem of building a new calendar by shipping a simple implementation in six weeks, then a better implementation six weeks after, and so on.

Fixing a delivery date and being flexible on the scope of what will be delivered bypasses the whole issue of inaccurate estimates. It embraces uncertainty and encourages error detection and correction.

I find risk diagrams and fixed deadlines with flexible scope better alternatives to story points, t-shirt sizes, and other estimate tracking systems.

Rather than ignoring the inherent unpredictability that comes with the job, they front load and account for it. They help us avoid fooling ourselves.

Does your team use estimates? What’s your experience been? If you’ve found a better alternative, shared it in the comments so we call all learn from it.

August 13, 2025

Five Definitions of Antifragility

Nassim Taleb’s profound and irreverent 2012 book Antifragile quickly became a best seller and, according to the author’s own boasting, is still selling very well.

Since its publication, the concept of antifragility has entered the business vernacular. After all, “being antifragile” seems like a worthy objective.

Predictably, a cottage industry of “antifragile for x” sprang up. From leadership to bodybuilding, mental health to running, medicine to sales, there’s plenty of material and “coaches” to help you become antifragile.

Some of the Amazon results for “Antifragile”

Some of the Amazon results for “Antifragile” Antifragility has become a buzzword—parroted often, implemented rarely. My guess is that many aspiring antifragilistas haven’t digested what antifragile actually means.

So, what does it mean to be antifragile? Here are five definitions, straight from the book.

To gain from disorder.

Anything that has more upside than downside from random events (or certain shocks) is antifragile; the reverse is fragile.

Fragility equals concavity equals dislike of randomness. [It follows: Antifragility equals convexity equals love of randomness.]

Antifragility is the combination aggressiveness plus paranoia—clip your downside, protect yourself from extreme harm, and let the upside, the positive Black Swans, take care of itself.

Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better. […] The antifragile loves randomness and uncertainty, which also means—crucially—a love of errors, a certain class of errors.

If you prefer visual analogies, think of antifragility as the Hydra monster.

These definitions show how multifaceted and elusive the concept is. There’s a lot to unpack from those few sentences alone, but I’ll leave that for another time.

In the meantime, if you take the time to read the book, you’ll appreciate how antifragility is easier to describe than to achieve.

That shouldn’t stop us from working toward antifragility, but it should temper our expectations of actually achieving it.

August 12, 2025

GPT-5 doesn't live up to the hype

On August 7, OpenAI released its long-awaited GPT-5 model… and it didn’t go well.

The most common reaction was disappointment.

At the time of writing, the Reddit post “GPT5 is horrible” has more than six thousand likes, and other complaints are getting similar feedback.

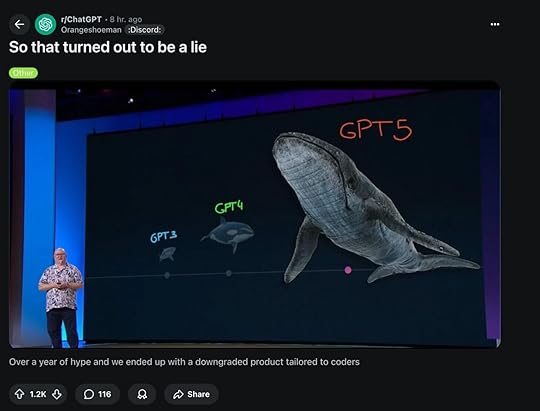

One of the trending posts showing disappointment after the launch.

One of the trending posts showing disappointment after the launch.OpenAI’s reaction to the launch shows the complaints aren’t just coming from the vocal Reddit crowd. In the days following the launch, the company released a “flurry of changes,” including making GPT-4o available for paid users. You know a new product is bad when you need to pay to use an older one.

But where does this disappointment come from?

Part of it is due to the genuine differences in how GPT-5 and GPT-4o respond to prompts, but my guess is that a lot of it comes down to unmet expectations.

OpenAI — and other LLM vendors — have been marketing their chatbots, smart autocompletion, and generative tools as getting ever closer to Artificial General Intelligence.

But AGI is the opposite of what OpenAI is building.

With general comes the ability to say no, the desire to pursue one’s own interests, and true creativity. But to improve ChatGPT, Claude, Grok, and the other models, their makers need to make them more obedient, which is incompatible with AGI.

GPT-5 suggests that bigger doesn’t mean smarter. As I noted when commenting on GPT-5 and Llama 4 Behemoth being delayed, AGI researchers might want to focus more on understanding how human minds work than on building ever-bigger data centers for training.

If we’re lucky, GPT-5’s flop will rein in the hype and the discourse will shift from “how AI will take over your job first, and the world next” to “when to pair with AI to be more productive at your job, and when to work solo.” And from there, private investment and public attention will shift from following the hype to solving concrete problems.

But the hype train is not easily derailed, and when companies depend on VC money, generating hype can take precedence over generating real value for users.

Time will tell.

August 8, 2025

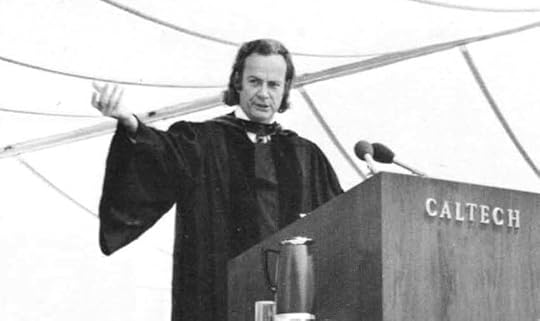

Cargo Cult Science by Richard Feynman

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.

— Richard Feynman

I am fond of sharing Feynman’s first principle. It’s a concise, powerful message for anyone interested in progress and getting closer to reality.

It’s easy to notice when other people have been fooled; much harder to notice when we have fooled ourselves. Yet that’s the first, and arguably most crucial, step. How can we criticize others if we haven’t first criticized ourselves?

When sharing quotes, there’s a danger you might be using them out of context. It’s always best to find the source in full.

The principle comes from a commencement address Feynman gave at Caltech in 1974, a lecture as thought-provoking as the snippet that is so often quoted.

Below is a full transcript, sourced from the Caltech digital library. I added some notes and I highlighted a few sentences in bold, but the italic emphasis comes from the original.

Cargo Cult Science

by Richard P. Feynman

Some remarks on science, pseudoscience, and learning how to not fool yourself. Caltech’s 1974 commencement address.

Source: Wikimedia, with edits.

Source: Wikimedia, with edits.

During the Middle Ages there were all kinds of crazy ideas, such as that a piece of rhinoceros horn would increase potency. (Another crazy idea of the Middle Ages is these hats we have on today—which is too loose in my case.) Then a method was discovered for separating the ideas—which was to try one to see if it worked, and if it didn’t work, to eliminate it. This method became organized, of course, into science. And it developed very well, so that we are now in the scientific age. It is such a scientific age, in fact, that we have difficulty in understanding how witch doctors could ever have existed, when nothing that they proposed ever really worked—or very little of it did.

But even today I meet lots of people who sooner or later get me into a conversation about UFO’s, or astrology, or some form of mysticism, expanded consciousness, new types of awareness, ESP, and so forth. And I’ve concluded that it’s not a scientific world.

The people who have difficulty understanding how witch doctors could ever have existed are children of the Enlightenment. They think rationally—or at least try to.

It easier for a scientifically minded person to forget that despite the advances brought by the scientific method, humans are also emotional beings.

This is not a scientific world, because despite all our science many of our actions are routinely driven by emotions.

But we should not despair, for being aware of the problem is the first step towards solving it.

Most people believe so many wonderful things that I decided to investigate why they did. And what has been referred to as my curiosity for investigation has landed me in a difficulty where I found so much junk to talk about that I can’t do it in this talk. I’m overwhelmed. First I started out by investigating various ideas of mysticism, and mystic experiences. I went into isolation tanks (they’re dark and quiet and you float in Epsom salts) and got many hours of hallucinations, so I know something about that. Then I went to Esalen, which is a hotbed of this kind of thought (it’s a wonderful place; you should go visit there). Then I became overwhelmed. I didn’t realize how much there was.

I was sitting, for example, in a hot bath and there’s another guy and a girl in the bath. He says to the girl, “I’m learning massage and I wonder if I could practice on you?” She says OK, so she gets up on a table and he starts off on her foot—working on her big toe and pushing it around. Then he turns to what is apparently his instructor, and says, “I feel a kind of dent. Is that the pituitary?” And she says, “No, that’s not the way it feels.” I say, “You’re a hell of a long way from the pituitary, man.” And they both looked at me—I had blown my cover, you see—and she said, “It’s reflexology.” So I closed my eyes and appeared to be meditating.

That’s just an example of the kind of things that overwhelm me. I also looked into extrasensory perception and PSI phenomena, and the latest craze there was Uri Geller, a man who is supposed to be able to bend keys by rubbing them with his finger. So I went to his hotel room, on his invitation, to see a demonstration of both mind reading and bending keys. He didn’t do any mind reading that succeeded; nobody can read my mind, I guess. And my boy held a key and Geller rubbed it, and nothing happened. Then he told us it works better under water, and so you can picture all of us standing in the bathroom with the water turned on and the key under it, and him rubbing the key with his finger. Nothing happened. So I was unable to investigate that phenomenon.

But then I began to think, what else is there that we believe? (And I thought then about the witch doctors, and how easy it would have been to check on them by noticing that nothing really worked.) So I found things that even more people believe, such as that we have some knowledge of how to educate. There are big schools of reading methods and mathematics methods, and so forth, but if you notice, you’ll see the reading scores keep going down—or hardly going up—in spite of the fact that we continually use these same people to improve the methods. There’s a witch doctor remedy that doesn’t work. It ought to be looked into: how do they know that their method should work?

I have many gripes with the education system, but I never stopped to reflect on what Feynman noticed some 50 years ago. Those whose methods failed are still in charge of improving them. How are we supposed to make any progress this way?

Another example is how to treat criminals. We obviously have made no progress—lots of theory, but no progress—in decreasing the amount of crime by the method that we use to handle criminals.

Yet these things are said to be scientific. We study them. And I think ordinary people with commonsense ideas are intimidated by this pseudoscience. A teacher who has some good idea of how to teach her children to read is forced by the school system to do it some other way—or is even fooled by the school system into thinking that her method is not necessarily a good one. Or a parent of bad boys, after disciplining them in one way or another, feels guilty for the rest of her life because she didn’t do “the right thing,” according to the experts.

So we really ought to look into theories that don’t work, and science that isn’t science.

One would expect that a theory that doesn’t work will soon be discarded, yet as Feynman observed that doesn’t seem to be the case. The lecture will soon suggest some ideas for why this happens.

The theoretical physicist David Deutsch also has a robust framework to diagnose and address the issue in his book The Beginning of Infinity, where he warns against explanationless science.

As we’ll see in the rest of the lecture, a problem with a lot of modern science—or, science only by name—is that it is not rooted in what Deutsch calls good explanations. A good explanation solves a problem in the real world and is hard to vary.

Good explanations also make verifiable predictions, but that’s not what makes them special. Bad explanations make verifiable predictions, too. The Sun rises every morning because Apollo pulls it into the sky with his chariot is a verifiable prediction, but a bad explanation. We could change Apollo with another deity that kicks the Sun into the sky instead of pulling it and it would all work the same way.

So the starting point needs to be an explanation that is hard to vary.

I tried to find a principle for discovering more of these kinds of things, and came up with the following system. Any time you find yourself in a conversation at a cocktail party—in which you do not feel uncomfortable that the hostess might come around and say, “Why are you fellows talking shop?’’ or that your wife will come around and say, “Why are you flirting again?”—then you can be sure you are talking about something about which nobody knows anything.

That remark isn’t just a joke to keep the audience engaged. It’s incredibly easy to fool ourselves into talking with strong opinions about topics we really don’t understand. See the Dunning-Kruger effect and Gell-Mann amnesia.

Using this method, I discovered a few more topics that I had forgotten—among them the efficacy of various forms of psychotherapy. So I began to investigate through the library, and so on, and I have so much to tell you that I can’t do it at all. I will have to limit myself to just a few little things. I’ll concentrate on the things more people believe in. Maybe I will give a series of speeches next year on all these subjects. It will take a long time.

I think the educational and psychological studies I mentioned are examples of what I would like to call Cargo Cult Science. In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

Now it behooves me, of course, to tell you what they’re missing.

Spoiler: Intellectual integrity and a tradition of criticism.

But it would be just about as difficult to explain to the South Sea Islanders how they have to arrange things so that they get some wealth in their system. It is not something simple like telling them how to improve the shapes of the earphones. But there is one feature I notice that is generally missing in Cargo Cult Science. That is the idea that we all hope you have learned in studying science in school—we never explicitly say what this is, but just hope that you catch on by all the examples of scientific investigation. It is interesting, therefore, to bring it out now and speak of it explicitly. It’s a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty—a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid—not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked—to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated.

Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can—if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong—to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it. There is also a more subtle problem. When you have put a lot of ideas together to make an elaborate theory, you want to make sure, when explaining what it fits, that those things it fits are not just the things that gave you the idea for the theory; but that the finished theory makes something else come out right, in addition.

This fits with thinking of theories as explanations and requiring them to be hard to vary. If a theory only explains the things that gave you the idea for it then it’s likely to be inductive and easy to vary.

But a good explanation “makes something else come out right, in addition”— it has reach. More on this in my recent post Explanations Have A Life Of Their Own.

In summary, the idea is to try to give all of the information to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not just the information that leads to judgment in one particular direction or another.

The best software developers I’ve worked with always propose designs together with a list of tradeoffs and pros and cons. By surfacing the rationale behind the proposal, they give themselves and their colleagues more chances to identify errors.

The easiest way to explain this idea is to contrast it, for example, with advertising. Last night I heard that Wesson Oil doesn’t soak through food. Well, that’s true. It’s not dishonest; but the thing I’m talking about is not just a matter of not being dishonest, it’s a matter of scientific integrity, which is another level. The fact that should be added to that advertising statement is that no oils soak through food, if operated at a certain temperature. If operated at another temperature, they all will—including Wesson Oil. So it’s the implication which has been conveyed, not the fact, which is true, and the difference is what we have to deal with.

We’ve learned from experience that the truth will out. Other experimenters will repeat your experiment and find out whether you were wrong or right.

You might have read about the current replication crisis. A staggering amount of published studies, often in the social and behavioral sciences, fails replication. See the work by the Data Colada team.

I’d venture to say that the situation today is even worse that in Feynman’s days. Observational studies that make bold claims get sensationalized by a press hungry for clicks. The authors gain notoriety and lofty consulting gigs with Fortune 500 and government agencies. In this system, there is little incentive to replicate, verify, or back track. See the Francesca Gino story for a vivid example.

I’m with Balaji Srinivasan when he argues for independent verification over prestigious citation.

Another example from the software world. Software developers write test code to verify the behavior of the app code. When fixing a bug, if the tests pass on the author’s computer but not on their colleague’s then it’s likely that the fix is incorrect or incomplete. For code to be approved, the tests need to pass on every machine that runs them. This independent verification is so important that teams have machines, often in the cloud, entirely dedicated to running tests.

Nature’s phenomena will agree or they’ll disagree with your theory. And, although you may gain some temporary fame and excitement, you will not gain a good reputation as a scientist if you haven’t tried to be very careful in this kind of work. And it’s this type of integrity, this kind of care not to fool yourself, that is missing to a large extent in much of the research in Cargo Cult Science.

The challenge today is that you might not get a good reputation as a scientist but you might still gain a huge audience of people listening to your claims or many lucrative consulting gigs.

A great deal of their difficulty is, of course, the difficulty of the subject and the inapplicability of the scientific method to the subject. Nevertheless, it should be remarked that this is not the only difficulty. That’s why the planes don’t land—but they don’t land.

We have learned a lot from experience about how to handle some of the ways we fool ourselves. One example: Millikan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right. It’s a little bit off, because he had the incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It’s interesting to look at the history of measurements of the charge of the electron, after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you find that one is a little bigger than Millikan’s, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher.

Why didn’t they discover that the new number was higher right away? It’s a thing that scientists are ashamed of—this history—because it’s apparent that people did things like this: When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong—and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number closer to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off, and did other things like that. We’ve learned those tricks nowadays, and now we don’t have that kind of a disease.

But this long history of learning how to not fool ourselves—of having utter scientific integrity—is, I’m sorry to say, something that we haven’t specifically included in any particular course that I know of. We just hope you’ve caught on by osmosis.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.

I would like to add something that’s not essential to the science, but something I kind of believe, which is that you should not fool the layman when you’re talking as a scientist.

One tell-tale sign of a charlatan is how much jargon they use. Whenever someone goes on a long ramble accumulating more and more technical terms, you can bet the reason is to distract, not to teach.

The best teachers try their hardest to make complex concepts simple.

I’m not trying to tell you what to do about cheating on your wife, or fooling your girlfriend, or something like that, when you’re not trying to be a scientist, but just trying to be an ordinary human being. We’ll leave those problems up to you and your rabbi. I’m talking about a specific, extra type of integrity that is not lying, but bending over backwards to show how you’re maybe wrong, that you ought to do when acting as a scientist. And this is our responsibility as scientists, certainly to other scientists, and I think to laymen.

For example, I was a little surprised when I was talking to a friend who was going to go on the radio. He does work on cosmology and astronomy, and he wondered how he would explain what the applications of this work were. “Well,” I said, “there aren’t any.” He said, “Yes, but then we won’t get support for more research of this kind.” I think that’s kind of dishonest. If you’re representing yourself as a scientist, then you should explain to the layman what you’re doing—and if they don’t want to support you under those circumstances, then that’s their decision.

One example of the principle is this: If you’ve made up your mind to test a theory, or you want to explain some idea, you should always decide to publish it whichever way it comes out. If we only publish results of a certain kind, we can make the argument look good. We must publish both kinds of result.

For example—let’s take advertising again—suppose some particular cigarette has some particular property, like low nicotine. It’s published widely by the company that this means it is good for you—they don’t say, for instance, that the tars are a different proportion, or that something else is the matter with the cigarette. In other words, publication probability depends upon the answer. That should not be done.

I say that’s also important in giving certain types of government advice. Supposing a senator asked you for advice about whether drilling a hole should be done in his state; and you decide it would he better in some other state. If you don’t publish such a result, it seems to me you’re not giving scientific advice. You’re being used. If your answer happens to come out in the direction the government or the politicians like, they can use it as an argument in their favor; if it comes out the other way, they don’t publish it at all. That’s not giving scientific advice.

Other kinds of errors are more characteristic of poor science. When I was at Cornell, I often talked to the people in the psychology department. One of the students told me she wanted to do an experiment that went something like this—I don’t remember it in detail, but it had been found by others that under certain circumstances, X, rats did something, A. She was curious as to whether, if she changed the circumstances to Y, they would still do, A. So her proposal was to do the experiment under circumstances Y and see if they still did A.

I explained to her that it was necessary first to repeat in her laboratory the experiment of the other person—to do it under condition X to see if she could also get result A—and then change to Y and see if A changed. Then she would know that the real difference was the thing she thought she had under control.

In software development, the first step to fix a bug is to reproduce it. This can be done manually, but I recommend using automated tests. Once the test that reproduces the bug is in place, developers can run the fix against it and “prove” that it works.

She was very delighted with this new idea, and went to her professor. And his reply was, no, you cannot do that, because the experiment has already been done and you would be wasting time. This was in about 1935 or so, and it seems to have been the general policy then to not try to repeat psychological experiments, but only to change the conditions and see what happens.

Nowadays there’s a certain danger of the same thing happening, even in the famous field of physics. I was shocked to hear of an experiment done at the big accelerator at the National Accelerator Laboratory, where a person used deuterium. In order to compare his heavy hydrogen results to what might happen to light hydrogen he had to use data from someone else’s experiment on light hydrogen, which was done on different apparatus. When asked he said it was because he couldn’t get time on the program (because there’s so little time and it’s such expensive apparatus) to do the experiment with light hydrogen on this apparatus because there wouldn’t be any new result. And so the men in charge of programs at NAL are so anxious for new results, in order to get more money to keep the thing going for public relations purposes, they are destroying—possibly—the value of the experiments themselves, which is the whole purpose of the thing. It is often hard for the experimenters there to complete their work as their scientific integrity demands.

All experiments in psychology are not of this type, however. For example, there have been many experiments running rats through all kinds of mazes, and so on—with little clear result. But in 1937 a man named Young did a very interesting one. He had a long corridor with doors all along one side where the rats came in, and doors along the other side where the food was. He wanted to see if he could train the rats to go in at the third door down from wherever he started them off. No. The rats went immediately to the door where the food had been the time before.

The question was, how did the rats know, because the corridor was so beautifully built and so uniform, that this was the same door as before? Obviously there was something about the door that was different from the other doors. So he painted the doors very carefully, arranging the textures on the faces of the doors exactly the same. Still the rats could tell. Then he thought maybe the rats were smelling the food, so he used chemicals to change the smell after each run. Still the rats could tell. Then he realized the rats might be able to tell by seeing the lights and the arrangement in the laboratory like any commonsense person. So he covered the corridor, and, still the rats could tell.

He finally found that they could tell by the way the floor sounded when they ran over it. And he could only fix that by putting his corridor in sand. So he covered one after another of all possible clues and finally was able to fool the rats so that they had to learn to go in the third door. If he relaxed any of his conditions, the rats could tell.

Notice Young’s methodical approach. Take away one thing at a time and see what changes.

Now, from a scientific standpoint, that is an A‑Number‑l experiment. That is the experiment that makes rat‑running experiments sensible, because it uncovers the clues that the rat is really using—not what you think it’s using. And that is the experiment that tells exactly what conditions you have to use in order to be careful and control everything in an experiment with rat‑running.

I looked into the subsequent history of this research. The subsequent experiment, and the one after that, never referred to Mr. Young. They never used any of his criteria of putting the corridor on sand, or being very careful. They just went right on running rats in the same old way, and paid no attention to the great discoveries of Mr. Young, and his papers are not referred to, because he didn’t discover anything about the rats. In fact, he discovered all the things you have to do to discover something about rats. But not paying attention to experiments like that is a characteristic of Cargo Cult Science.

Another example is the ESP experiments of Mr. Rhine, and other people. As various people have made criticisms—and they themselves have made criticisms of their own experiments—they improve the techniques so that the effects are smaller, and smaller, and smaller until they gradually disappear. All the parapsychologists are looking for some experiment that can be repeated—that you can do again and get the same effect—statistically, even. They run a million rats—no, it’s people this time—they do a lot of things and get a certain statistical effect. Next time they try it they don’t get it any more. And now you find a man saying that it is an irrelevant demand to expect a repeatable experiment. This is science?

This man also speaks about a new institution, in a talk in which he was resigning as Director of the Institute of Parapsychology. And, in telling people what to do next, he says that one of the things they have to do is be sure they only train students who have shown their ability to get PSI results to an acceptable extent—not to waste their time on those ambitious and interested students who get only chance results. It is very dangerous to have such a policy in teaching—to teach students only how to get certain results, rather than how to do an experiment with scientific integrity.

I don’t have a background in physics, so I might be off here—please do point it out if I am—but the above reminds me of the “shut up and calculate” approach to quantum mechanics.

So I wish to you—I have no more time, so I have just one wish for you—the good luck to be somewhere where you are free to maintain the kind of integrity I have described, and where you do not feel forced by a need to maintain your position in the organization, or financial support, or so on, to lose your integrity. May you have that freedom. May I also give you one last bit of advice: Never say that you’ll give a talk unless you know clearly what you’re going to talk about and more or less what you’re going to say.

When I went looking for the source of the “you’re the easiest one to fool” quote, I wanted to make sure I wasn’t misusing it.

But as so often happens when you set out to deepen your understanding, what I got in return was much more valuable.

Following the quote trail revealed an engaging and thought-provoking lecture. An ode to intellectual integrity. A call to hold ourselves to the highest standards and to “bend over backwards” to show how we might be wrong.

What a gift!

April 10, 2025

The Rubber Duck Now Quacks Back

Rubber ducking in the age of AI.

Large language models (LLMs) are versatile tools. You can use them as artificial interns1 to generate draft for you, feed them documents to summarize, proof read, and more. An LLM can generate a training plan for you, propose a travel itinerary, or help you adjust the tone of an important message you are writing.

Another way to put LLMs to work is for rubber ducking. But with a twist—the rubber duck quacks back!

Rubber ducking is a common practice among software developers. The name comes from The Pragmatic Programmers, where Dave Thomas recalls how a colleague used to work with a rubber duck on top his terminal and describe the problems he was stuck on to it.

When describing a coding problem out loud, “you must explicitly state things that you may take for granted when going through the code yourself.” This is often enough to generate insight into the problem and make progress. And this works in any creative field, not just programming.

Notice that it’s the act of describing the problem that is valuable. The result is the same whether you talk to a real person or to a rubber duck.

Talking to an inanimate object has the advantage of not distracting your colleagues. But there are times where describing a problem is not enough and you could benefit from a probing question or the push back.

So why not talk to an LLM?

With AI, rubber ducking takes on a new level. This digital rubber duck quacks back, can judge your idea, help you sharpen them, and suggest alternatives. All without disturbing your teammates.

With ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok, we all have at our fingertips a squad of interactive rubber ducks that are smart, patient, and always available.

But no matter how refined they are, we need to remember that LLMs are far from error-proof. On top of that, many LLMs will do their best to please you, but when problem solving it’s criticism that you need most.

You wouldn’t ship the work your intern made without first looking over it, whether the intern is a human or a bot. Likewise, you cannot trust everything a toy duck tells you, whether it’s made of rubber or bits.

Remember Feynman’s words: “You are the easiest one to fool.” Don’t let an LLM tuned to please its user lull you into thinking you discovered the best solution.

Dave Thomas’ rubber duck never validate your ideas, it only gave you space to understand them. These digital rubber ducks might quack back, but of all the work we ought to delegate to AI, thinking remains our responsibility.

1 — The article used DALL-E to show how much guidance a generative AI needs, and how many iterations are required to get to a satisfying result. Since then, image generation has leapfrogged both in prompt understanding and output quality. The intern has gotten much better, but it’s still an intern. AI has no initiative or genuine creativity. You need to tell it what to do.

Thanks to Alex Grebenyuk for the conversation that resulted in this post.

April 8, 2025

The Art of Exploration is a Lifelong Pursuit

Our world is too dynamic to ever stop exploring.

In episode 1,062 of The Art of Manliness, The Art of Exploration — Why We Seek New Challenges and Search Out the Unknown, Brett McKay interviews Alex Hutchinson, author of The Explorer’s Gene.

They touch on the explore-exploit problem: when do you stop exploring new things and double down on what you know works?

I won’t get into the explore-exploit details, check out Alex’s book and Algorithms To Live By for a deep dive on the topic. In short, the rational solution would be to progressively explore less and exploit more. The older we get, the less we should explore.

But while the math does not lie, there’s something uncomfortable with the idea of stopping to explore, isn’t there? Does being rational mean giving up on novelty and settle for eating the same meal at the same restaurant, listening to the same album, and re-watching the same movie?

Brett and Alex both agree that there must be more to it than the raw math, and offer two reasons for why one ought to keep exploring.

The first is that as our life expectancy increases, we can explore for many more years than our ancestors. I don’t like this explanation because it simply pushes the problem later in the future. That we can explore in our sixties does not address what to do in our eighties. Besides, one could argue that since we live longer we have more time to exploit and accrue benefits that way.

The second reason Brett and Alex offer for continuing to explore is that exploring simply feels good. Once you factor into the explore-exploit model the value you get from trying new things for the sake of it, mere exploitation becomes less attractive. Exploring is inherently valuable because it breaks monotony and gives us new experiences.

Here’s a third reason to add into the mix. We should keep exploring because the future does not resemble the past.

Explore-exploit assumes a static world. When nothing changes, finding a local maximum to exploit can indeed generate lots of value over time.

But our world is in constant flux. We live in a time where more and more is being created by more and more people thanks to technology liberating us from rote labor.

The more creativity, the more the future becomes unpredictable. The value landscape is fluid, the peak you find today might be greatly overshadowed tomorrow.

So, never stop exploring. Even the day before you die, keep exploring.

I’ll leave you with a quote often attributed to Mark Twain but that apparently comes from H. Jackson Brown, Jr. mother’s:

Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.

April 5, 2025

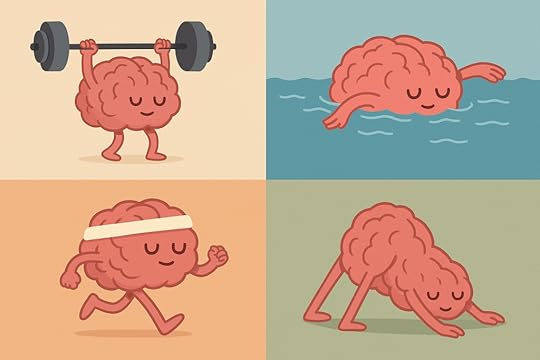

A training plan for cognitive fitness

To get smarter, you need to put in the reps.

In two recent episodes of his podcast Deep Questions, Cal Newport shared a training plan for cognitive fitness.

The episodes are #345: Are We Getting Dumber? and #346: Getting Smarter in a Dumb World. I recommend watching them, but here’s an annotated summary.

Level 1: Maintaining cognitive fitnessThese are the cognitive equivalent of daily movement, hydration, and sleep. The basics to counteract the effect social media, work chats, and…

ReadAs Cal is fond of saying, “reading is calisthenics for the brain.” And while listening to books is valuable, it’s reading on paper that really trains your brain—see The Reader’s Brain for more details. It doesn’t matter what you read; anything goes, from pulp paperback fiction to dense idea books.

Pursue cognitively demanding hobbiesWhether it’s playing an instrument, learning a manual craft, or my recent favorite, solving twisty puzzles, engage in leisure activities that require concentration. This will keep you entertained in an active way, as opposed to the passive doomscrolling that shrinks your attention span.

Go on reflection walksWalking has many positive effects for the body. You can double dip by using walking to train your concentration. Pick up a problem to reflect upon and focus on it during your walk. When you notice your attention wandered off, gently push it back on track. (See also How To Walk More Without Changing Your Schedule.)

Avoid stimuli stackingSmartphones are so convenient to carry around and the social media apps so engaging that you can find yourself watching TV while scrolling on Instagram. This growing tendency damages our ability to focus, because the brain gets used to distractions. It also takes away from the experience: if you divide your attention between TV and Instagram, you’ll enjoy neither. I often fall into this with podcasts at lunchtime. I’ll eat while listening to something and get to the end of my meal without having enjoyed a single bite.

Level 2: Improving cognitive fitnessIf you think of the exercises above as the equivalent of keeping your body in motion, getting enough rest, and following a healthy nutrition, then the following exercises are like following a training plan to compete in a triathlon. They are meant to take your cognitive fitness to the next level.

Dialectical readingWhen interacting with ideas, intentionally seek opposite views. This exercise will force you to engage with ideas seriously, questioning your assumptions and criticizing the opposition. The goal is not to change your mind, it’s to put it through a rigorous exercise.

Become a connoisseurTake your hobby up a notch by becoming a student of it. Dive deep into the history and the details to develop taste. This deeper level of engagement requires focus and dedication, which is a great exercise for the mind. It will also raise the quality bar you’ll accept for your inputs, another safeguard against the kind of leisure activity that degrades your focus.

Keep an ideas documentMoving from input to output is another method of interacting with ideas that benefits your cognition. Write about the ideas you care about as an exercise to deepen both your understanding and your thinking—for clear writing is clear thinking.

Focus interval trainingHow long can you engage with a problem without caving in to distractions? Can you stick with something for 90 minutes, without checking Slack, or your phone, or whichever quick fix for boredom you use? These are questions of focus endurance, a skill that can be systematically improved. Whatever your current level, aim for 10 minutes more over the next two weeks. Obviously, the interval can’t stretch indefinitely, but 90 minutes is a duration often recommended as the sweet spot between having enough time to make progress without depleting the brain’s fuel and stamina to the point where it can no longer perform.

Curate your digital dietThis final advice is more of a practice than an exercise to repeat. Think of it as the equivalent of eating the right food to fuel muscle recovery as part of your training plan. Today’s digital entertainment and information landscape is unfortunately optimized for shallowness and emotional engagement. As I wrote in The Sherlock Holmes Information Diet, “when fed a diet of trivial nonsense, our brains will never have the raw materials for producing deep thoughts.”

Cal’s exercise regimen for cognitive fitness came as a reaction to the provocative Financial Time piece by John Burn-Murdoch Have humans passed peak brain power? (paywalled). For what is worth, I agree with James Pethokoukis in thinking we are far from a peak. In fact, we might be at the beginning of a new climb thanks to more technological augmentation—but, this is just me prophesying.

Regardless of what some observational studies find about the cognitive prowess of their participants, we can all benefit from training our brain.

As a father, how well I can focus impacts both the quality of the time I spend with my kids and my ability to earn a living for them.

Cal’s exercises might not address the root causes of what can sometimes feel like an incurable distraction epidemic, but are a great way for individuals to strengthen their immune system against it. “All you need to do” is put in the reps.