Judith Hale Everett's Blog, page 5

October 21, 2020

Can or Can Not–There Is No Try

It’s amazing how many mundane matters conspire to thwart a writer once they’ve gotten on a roll. It seems that whenever I have nothing planned for the week, as soon as I settle into a rhythm with writing, something comes up—then something else, and something else…

It’s Murphy’s law, I guess, and there’s nothing I can do about it.

But really, what would I want to do about it? Almost every one of my mundane matters has to do with my family, so if I wished away everything but writing, where would I be? Pretty sad and pretty lonely, that’s where.

So what brings all this philosophizing on? Well, canning season has finally come to a close. (Hallelujah!) Yes, I am part of a sisterhood of crazy people who till up their lawn so they can plant a bunch of stuff so they can put it into jars and into the dehydrator so they can fill up shelves in their basement against the end-times.

My outdoor canning setup—we may be crazy, but we’re crazy smart

My outdoor canning setup—we may be crazy, but we’re crazy smartActually, we start eating our preserved food almost as soon as we put it up, and it’s a good thing COVID hit in March, because we still had plenty to tide us over through the mad rush on the stores at the beginning of quarantine. In fact, it was the first time we have had to rely on our storage to survive (not just pretend), which was surreal. I felt so not-crazy all of a sudden. So it was all worth it.

But it’s always worth it, even when I have to break into my sacred writing time to bust out 40 quarts of apple juice, or 7 batches of grape leather, or 35 pints of stewed tomatoes. There’s really no satisfaction like work well done–and work well done for someone else is even better. The look on my kids’ faces as they drink our homemade grape juice is worth all the writing time in the world.

Well, at least several hours anyway.

October 5, 2020

My Regency Love Affair

Few eras in history are as romanticized as the Regency era. But what is it about that time in history that so many of us love?

When I think of the Regency, I think of impeccable manners and careful dress, grand balls with elegant dancing, sweeping vistas of the countryside, men being dashing and treating women with courtesy, and women being gentle and graceful (but always quick and witty). But the more I have read, and especially the more I have studied about the era, I’ve had to acknowledge that my view of the Regency is not completely accurate.

Did men always treat women with courtesy? Well, a true gentleman always stood when a lady came into the room, offered a hand or an arm to support her in any exertion (such as ascending or descending anything from stairs to the carriage step), never allowed a vulgar word to escape his lips in her presence, and was ready to defend her honor at any provocation. But some “gentlemen” took for granted that only gently-born (titled or wealthy class) women should expect such treatment, and women of lower birth (especially of the serving classes) were fair game for anything from a pinch on the butt to an indecent proposal. Which is extremely offensive to me.

Was life all beautiful clothing and elegant parties? Unfortunately, only a very small percentage of the population enjoyed the ease and comfort we love to associate with the Regency period. All that elegance was made possible by members of the working class, whose services were essential to the comfort of their employers, but who eked out a living on mere shillings to pounds a year. While the middle and upper classes had nothing to do all day but visit and drive in the park and gather flowers and embroider and go to parties, their servants were sewing and washing and ironing and cleaning and cooking and grooming and mucking and shoeing and–well, you get the idea. And it kind of sours the lovely vision Jane Austen gave us.

As I’ve thought about this quandary, I’ve come to realize that though I have serious issues with the way many things were in the Regency era, I still am in love with it, and it’s not because of any of the superficial things we associate with the time. The elegance and manners and dress and dancing are all just a backdrop. What I love are the stories of strong people who were unafraid to be themselves, and who defied the status quo–sometimes quietly and subtly, which is almost more powerful–to make wonderful, impossible things happen.

Consider that gentlewomen were raised to believe that men were intellectually superior, and must be treated as such. But many women, Jane Austen included, didn’t subscribe to this view, instead speaking their minds and making their way in the world whether or not the men appreciated it. And many did appreciate it, being bored to death by propriety and welcoming a good challenge to the status quo. Several men, it turns out, not only revered the gentle sex, but respected them as well.

Also consider that social lines were solidly drawn. Where you were born is where you will stay. Well, according to some insurance policies of the time, a lot of “low-born” people were able to amass quite a few possessions, which opened the doors to social possibilities. Now, most social climbers would be labeled “mushrooms” and ostracized by the ton, but occasionally, as in the case of Lord Hardwicke, the son of a silversmith, nobodies made it into acceptable circles with whatever skills or attributes they could muster. And the children of “mushrooms” could often blend right into higher circles because their enterprising parents raised them “gently.”

What it boils down to is that even though every era has its dark sides, it is inspiring to see how people can not only resist being broken by adverse circumstances, but rise above them, in any time period. And it doesn’t hurt if their clothing and dance steps and manners happen to be classy, too.

Everything’s better with a British accent, right?

October 2, 2020

The Latest On-Dits

It’s funny how we tend to think of our society as so much more mature than those of the past. We laugh a little at their simplicity, shrug or shake our heads at their ideas and ideals, and generally feel smug about our superiority.

Don’t get me wrong—we have come a long way in the last two centuries. Some of the more blatant social wrongs have begun to be righted and the civilized world is generally a safer, more humane place. But inherently, we are still as human as our predecessors.

Take this passage I came upon in the preface to a collection of Jane Austen’s letters, published in 1892. The author, considering Austen’s life, said,

It was a short life, and an uneventful one as viewed from the standpoint of our modern times, when steam and electricity have linked together the ends of the earth, and the very air seems teeming with news, agitations, discussions. We have barely time to recover our breath between post and post; and the morning paper with its statements of disaster and its hints of still greater evils to be, is scarcely outlived, when, lo! in comes the evening issue, contradicting the news of the morning, to be sure, but full of omens and auguries of its own to strew our pillows with the seed of wakefulness.

To us, publications come hot and hot from the press. Telegraphic wires like the intricate and incalculable zigzags of the lightning ramify above our heads; and who can tell at what moment their darts may strike? In Miss Austen’s day the tranquil, drowsy, decorous English day of a century since, all was different. News traveled then from hand to hand, carried in creaking post-wagons, or in cases of extreme urgency by men on horseback…; there was little chance of frequent surprises…. No doubt they lived the longer for this exemption from excitement, and kept their nerves in a state of wholesome repair.

Letters of Jane Austen, selected by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, 1892; Preface

Reading that was almost surreal. Change it to modern-speak and it could be describing 2020, pretty much to a T. It’s still all about the news: local news, friend news, world news, frenemy news, national news.

Posting in Regency times

Posting in Regency timesBut the Victorian author of the above was just as guilty as we are in patting the head of the Regency and sending it out to play. If news traveled slowly during the Regency, it was only in the country, because the latest on dits traveled like wildfire in town. The ton and the lower classes alike thrived on the latest news, which passed rapidly by word of mouth, but was expedited further by several newspapers which vied for followers by publishing what they knew would tantalize or even shock their readers into wanting more. With this continuous circulation of news, people lived in the constant expectancy of some scandal involving persons they disliked, and in fear of any breath of scandal attaching to themselves.

Things haven’t changed much. While our lives may be even more fast paced, with vehicles traveling up to the speed of sound, and the time between “post and post” only seconds, we still can’t wait for the latest news. We still thrill at the rise and fall of public figures, and hope to out-do our neighbors on Facebook or Instagram with better and cooler pictures or posts. About the only change from the Regency to now has been in the volume of information immediately available to the general public, and in the scope of the news offered, which exactly matches the trend implied by the above observation from 1892.

Luckily, the average life expectancy has not also followed the trend above, but that may be for the next generation to suffer; the author of the quote was right on the money with her belief that the state of humanity’s nerves would be in no way helped by the increasing bombardment of media on our senses. Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad to return to the quiet country life of Jane Austen’s day–at least once in a while.

For the Love of News

It’s funny how we tend to think of our society as so much more mature than those of the past. We laugh a little at their simplicity, shrug or shake our heads at their ideas and ideals, and generally feel smug about our superiority.

Don’t get me wrong—we have come a long way in the last two centuries. Some of the more blatant social wrongs have begun to be righted and the civilized world is generally a safer, more humane place. But inherently, we are still as human as our predecessors.

Take this passage I came upon in the preface to a collection of Jane Austen’s letters, published in 1892. The author, considering Austen’s life, said,

It was a short life, and an uneventful one as viewed from the standpoint of our modern times, when steam and electricity have linked together the ends of the earth, and the very air seems teeming with news, agitations, discussions. We have barely time to recover our breath between post and post; and the morning paper with its statements of disaster and its hints of still greater evils to be, is scarcely outlived, when, lo! in comes the evening issue, contradicting the news of the morning, to be sure, but full of omens and auguries of its own to strew our pillows with the seed of wakefulness.

To us, publications come hot and hot from the press. Telegraphic wires like the intricate and incalculable zigzags of the lightning ramify above our heads; and who can tell at what moment their darts may strike? In Miss Austen’s day the tranquil, drowsy, decorous English day of a century since, all was different. News traveled then from hand to hand, carried in creaking post-wagons, or in cases of extreme urgency by men on horseback…; there was little chance of frequent surprises…. No doubt they lived the longer for this exemption from excitement, and kept their nerves in a state of wholesome repair.

Letters of Jane Austen, selected by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, 1892; Preface

Reading that was almost surreal. Change it to modern-speak and it could be describing 2020, pretty much to a T. It’s still all about the news: local news, friend news, world news, frenemy news, national news.

Posting in Regency times

Posting in Regency timesBut the Victorian author of the above was just as guilty as we are in patting the head of the Regency and sending it out to play. If news traveled slowly during the Regency, it was only in the country, because the latest on dits traveled like wildfire in town. The ton and the lower classes alike thrived on the latest news, which passed rapidly by word of mouth, but was expedited further by several newspapers which vied for followers by publishing what they knew would tantalize or even shock their readers into wanting more. With this continuous circulation of news, people lived in the constant expectancy of some scandal involving persons they disliked, and in fear of any breath of scandal attaching to themselves.

Things haven’t changed much. While our lives may be even more fast paced, with vehicles traveling up to the speed of sound, and the time between “post and post” only seconds, we still can’t wait for the latest news. We still thrill at the rise and fall of public figures, and hope to out-do our neighbors on Facebook or Instagram with better and cooler pictures or posts. About the only change from the Regency to now has been in the volume of information immediately available to the general public, and in the scope of the news offered, which exactly matches the trend implied by the above observation from 1892.

Luckily, the average life expectancy has not also followed the trend above, but that may be for the next generation to suffer; the author of the quote was right on the money with her belief that the state of humanity’s nerves would be in no way helped by the increasing bombardment of media on our senses. Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad to return to the quiet country life of Jane Austen’s day–at least once in a while.

March 6, 2020

Publishing’s Marriage Mart

Submitting to agents is much like being thrown on the Marriage Mart.

Dancing at Almack’s

Dancing at Almack’sMy last two novels being Regency romances, I couldn’t help but make this comparison when I went through the grueling process of submitting my manuscript to agents. And after feeling terribly sorry for myself, and eating myself out of chocolate, it occurred to me that at least I had it better than those poor girls! At least I have other things I can do with my life, and my mortification is entirely private. They were all so young, most still in their teens, and foisted onto the public stage to make a creditable (if not brilliant) match, or go home in disgrace.

No pressure!

If any of you have submitted to agents, you know what I’m saying here. For those who haven’t, well, you spend countless hours, days, months creating and polishing a work of art that fills you with excitement, and that your readers love and assure you must be on the shelves of every bookstore without delay. So you decide it’s time to submit, and begin to research agents who are interested in your type of storytelling, only to learn how pointless and ridiculous are all your dreams, because agents are only interested in perfection of a certain kind, that exudes uniqueness and spark while addressing the world’s problems in a subtle yet powerful voice, all in language that would fall from the lips of angels.

But you must submit. So, somehow, you scoop the dribbling remnants of your self-esteem up off the floor and present your life’s work, in the forlorn hope that perhaps one of these gods of the publishing world will see past all its failings to the diamond at its heart. Agent after fastidious agent you importune, bowing to their every submission guideline whim, walking the fine line of appearing interesting and confident without being pushy or weird, and re-inventing the wheel of your approach with almost every agent, because they have already established themselves in the industry and can be as quirky as they like.

It was some comfort to me to realize that it must have been much the same on the Marriage Mart. Each young lady between the ages of seventeen and twenty (and sometimes younger), having been fortified for success with a steady diet of strict etiquette, maidenly gentility, and feminine accomplishments, made their come out into Society with starry-eyed dreams and aspirations, and very little true understanding of what awaited them. Some were better prepared than others, but all were subjected to the close scrutiny of everyone from the censurious matron, to the loose screw, to the reigning beauty, to the exacting Corinthian. Every young lady was publicly weighed in the balance time and again, and very often publicly found wanting, in one way or another, despite their careful training and individual strengths.

It was as much of a polite cat fight as us poor writers are engaged in, smiling and batting our eyes at those who could give us an entre’ to the world of which we so desperately wish to be part, while sinking our claws into any opportunity that might forward our cause. The sheer inhumanity of it can be depressing.

But we must not forget the Lizzie Bennetts of the Regency world, who never gave themselves up to falsity or imposture, no matter the pressure they endured to be what others thought they should be, who humbled themselves when necessary, and who persevered through snubs and even outright persecution. These were the strong women of their age, who blazed their way through and around the strictures and expectations of their world to find true happiness, and captured the imaginations of millions a century and more later.

It has been said, “What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger.” (Pretty sure Nietze said that) And so, just as those intrepid maidens of two hundred years ago did what it took to reach their dreams and remain human, so can we, and we will not only live to tell the tale, but may just inspire future generations to gird up their loins and do hard things as well.

February 1, 2020

Knitting, Netting, Knotting, Needlework

Two women sewing

Two women sewingThere was a great deal of needlework to be done, moreover, in which her help was wanted.

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen, p. 76

Gently-born ladies of the Regency era seemed always to be out and about (especially as portrayed in books or movies), gone to card parties or balls or picnics, or going on long walks, or at the very least, welcoming visitors into their drawing rooms for a lively half hour at a time.

However, between the visits and the balls and parties, there were many hours in the day where these ladies would have been idle, had they not some sort of occupation to keep them busy. Remember that middle- and upper-class households employed servants to do all menial tasks (how awesome would that be?) such as laundry, ironing, dusting, cleaning, cooking, and any errands the ladies of the house did not wish to do. So what did those ladies DO with themselves in the dreary quiet hours?

Sewing and Embroidery

Regency-era sewing box, as seen in an antique shop window, Bath UK

Regency-era sewing box, as seen in an antique shop window, Bath UKMy dear Catherine, I do not know when poor Richard’s cravats would be done, if he had no friend but you.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, p. 104

We often hear of a lady’s putting aside her embroidery or sewing in order to attend to a visitor, and the image I’ve always gotten was of a frilly little piece that, once framed, would join the rest of the frilly pieces lining the walls of the ancestral home. But more often than not, those sewing or embroidery projects were actually entirely useful; women regularly spent their leisure hours hemming shirts or cravats, sewing their own gowns (if they enjoyed it or couldn’t afford the services of a modiste), or embellishing various articles of clothing, like gowns, waistcoats, fichus, etc.

https://donnahatch.com/regency-gentlemens-waistcoats/

https://donnahatch.com/regency-gentlemens-waistcoats/ https://www.meg-andrews.com/item-details/Embroidered-Fichu/8881

https://www.meg-andrews.com/item-details/Embroidered-Fichu/8881Knitting

French woman knitting

French woman knittingShe taught me to knit, which has been a great amusement; and she put me in the way of making these little thread-cases, pin-cushions and card-racks, which you always find me so busy about, and which supply me with the means of doing a little good to one or two very poor families in this neighbourhood.

Persuasion by Jane Austen, p. 69

Knitting, which was much the same then as it is now, was another essential skill for ladies, as the articles made were excessively useful: scarves, mittens, wrappers, shawls, socks, slippers, nightcaps, etc.

Fingerless gloves, mfa.org

Fingerless gloves, mfa.orgNetting

Regency era netting box

Regency era netting boxMiss Andrews is netting herself the sweetest cloak you can conceive.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, p. 13

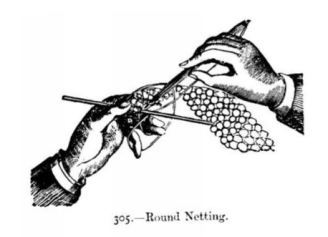

Netting is a much lesser-known needle art today, but it was just as common as knitting or sewing during the Regency. Considered by many to be one of the simplest forms of needlework, it still required specialized tools, as seen in the picture above. Netting had various applications, and took relatively little time to complete a project. It was similar to crochet, and involved creating a series of loops that could be enlarged or reduced and alternated to create patterns. Ladies netted purses, lace edgings, and even capelets (or cloaks).

Netted purse

Netted purse Netted lace

Netted laceIsabella Beeton’s Book of Needlework, which includes step-by-step instructions on netting, can be found online, for anyone curious enough to understand exactly what netting entails.

Knotting

Knotted fringe

Knotted fringeHer own time had been irreproachably spent during his absence: she had done a great deal of carpet-work, and made many yards of fringe.

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen, p. 80

It seems that fringe was the chief end of knotting in the Regency, and it was used to edge anything from curtains to clothing to piano rugs. A fairly simple form of needlework, knotting could be done by the least accomplished lady, and even by men (not that they were unaccomplished), as evidenced in a letter from Jane Austen to her sister Cassandra, by a reference to their brother Frank knotting fringe while he was home on leave from the Navy, and ill.

According to the article, “How to make knotted fringe” on janeausten.co.uk, “Knotted fringe is actually quite easy to make and can be a lovely addition to any number of projects. The first thing you must decide is whether your project requires the addition of fringe or whether the fringe can be knotted from existing strands.” So fringe could be made independently and sewn onto something, or made from the fibers of the desired article, if they were of appropriate thickness and strength.

Fringe made from fibers of a cloth

Fringe made from fibers of a clothKnotting instructions can also be found online at http://knittingsitting.blogspot.com/.

Overall, gently-born ladies did have plenty of useful things to do with their time, even with servants doing so much–and this isn’t even the half of it! But that’s for another blog post…

January 26, 2020

Heat, Smoke, and Slavery

A Rumford fireplace, from www.rumford.com

A Rumford fireplace, from www.rumford.comThe fire-place where she had expected the ample and ponderous carving of former times, was contracted to a Rumford, with slabs of plain, though handsome, marble, and ornaments over it of the prettiest English china.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, p. 68

Like Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, few modern readers can appreciate a good fireplace. With modern conveniences like electric radiators and gas fireplaces, even super-effective wood-burning stoves, we seldom even think about the pleasures of a good fire for everyday comfort.

But in an era when all heat came from the fireplace, considerations of efficiency and comfort were paramount. For centuries, people rich and poor relied on the scant heat given by the typical open hearth or square fireplace, while most of the heat escaped up the chimney.

But in 1796, Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, publicized his design for a narrow-chimneyed fireplace, which allowed for upward circulation of air, taking the smoke up and out of the house while the heat radiated into the room. His designs were immediately recognized as state-of-the-art and implemented in many great houses, and became the preferred style.

Safety was still an issue, however, as bits of burning wood or embers could be ejected from the fireplace onto the rug, or worse, onto the clothing of the people sitting close by the fire for warmth.

Enter the fender, a decorative but useful frame set around the edge of the hearth to catch these troublesome pieces.

(A fireplace with a fender; illustration for Northanger Abbey by Hugh Thompson)

Smoke was always a problem, though, even in a Rumford, if soot was allowed to build up in the chimneys. In the early 19th century, with chimneys reaching from the ground floor of a house all the way through sometimes six floors to the roof, the only thing to be done was to send a small child climbing up with a brush to scrape off the accumulation.

These “climbing boys” were not always male, but they were always underfed (to keep them skinny enough to manage the flues) and ill-treated, if not abused–like the climbing boy in Arabella by Georgette Heyer. There simply was no motivation for their masters to treat them well. They were often orphans, either taken off the streets or bought from poor homes, so there was no one to love or care for them. Their masters felt like their “goodness” in giving them a home was reason enough to take all the pay, and to treat the children no better than rats in the basement. Thousands of climbing boys died each year from burns, suffocation, chimney collapse, or cancer, but this didn’t bother their masters. There were always more orphans.

Birmingham climbing boys; newsela.com

Birmingham climbing boys; newsela.comThe horror of this situation was recognized as early as the late 1700s, but though an Act was passed that regulated the treatment and duties of chimney sweeps, no system was put in place to enforce it. Several societies were formed to relieve the climbing boys, but their efforts were not widely accepted, as people were more concerned about house fires caused by inefficient chimney cleaning than for the welfare of a set of scrubby little brats. In 1796, the London Society for Superseding the Necessity for Employing Climbing Boys was founded, which promoted a competition to create a mechanical brush, but the winning brush did not become popular enough to eliminate the demand for climbing boys.

Several years later a sufficient public outcry prompted Parliament to pass the Chimney Sweeper’s Act of 1834, which did much to alleviate the plight of the climbing boys by raising minimum age and restricting their master’s power, but again enforcement was spotty. It was not until the widely-publicized death of George Brewster, an underage climbing boy who became stuck in the flue and suffocated in 1875, that a final bill was passed outlawing climbing boys, with sufficient riders to ensure enforcement.

All I can say is thank goodness those days are over, and that people were finally willing to stand up for those little boys’ lives. I have a real fireplace, but the flue is only two storeys tall, and is cleaned by a mechanical brush. I can’t even imagine sending one of my little boys up there, for any reason (though they might think it could be a fun adventure). I love the look of cheery flames in the hearth on a wintry night, if I had to choose, I would take my central heating any day, and be grateful.

January 19, 2020

The Home Wood

photo Joe Everett

photo Joe EverettThe undulations of a lawn shaved all summer by scythemen were broken by a cedar, and beyond the lawn the stems of beech-trees, outliers of the Home Wood, shimmered in wintry sunlight.

Sylvester or the Wicked Uncle by Georgette Heyer, p. 1

I had never come across the phrase “Home Wood” in my historical reading before Georgette Heyer, and though I figured I knew what it was, I wanted to be a good writer and do my research before I wantonly used an unfamiliar phrase in my own work.

So I looked…and looked…and looked. I could find no references–encyclopedic, botanical, or historical–using Home Wood. Well, Heyer has done this to me before–using a phrase no one else seems to have thought to document. The best I could find was a kind of obliquely comparative phrase: the Home Counties of England.

The Home Counties are most broadly defined as the counties surrounding London, and many historians consider only the five closest counties as included in the definition. The earliest use of this phrase was recorded in the 17th century, but no one seems to know where it came from or why it was perpetuated.

How does this have anything whatsoever to do with “Home Wood”? Well, call me desperate, but I think there is a connection in how the word “Home” is used in both phrases. The Home Counties surround, or are closest to, the principle city in the country, while the Home Wood surrounds, or is closest to, the principle seat in the area.

Though proud of my findings, I nevertheless thought them a pretty weak support for my using the phrase in my own work. But before giving up hope of finding anything more definite, I decided to use the Hathi Trust (the most amazing resource for language in the world–I am in love with it!) to search period writings for this phrase–and couldn’t find it. Well, at least not for a while. I found plenty of “home” and plenty of “wood” but never both used together as a title.

Until, at last, I came across a little history of Norfolk where it was used, not once, but TWICE!

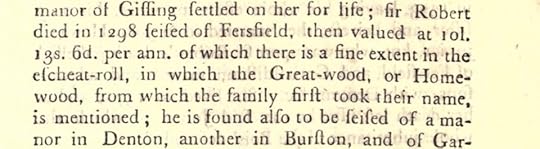

The History and Antiquities of the County of Norfolk, V. 2, 1781 p. 91

The History and Antiquities of the County of Norfolk, V. 2, 1781 p. 91 The History and Antiquities of the County of Norfolk, V. 2, 1781 p. 119

The History and Antiquities of the County of Norfolk, V. 2, 1781 p. 119(P.S. Half of the f’s in this book are actually s’s, because that’s how they used to do it until the turn of the 19th century. It’s called the long s, and is printed as an f without the crossbar (look closely in the above images and you can barely see the difference). The long s was used generally at the beginning and middle of a word (with a few exceptions), and as the first s in a double (as in succefs), while the round s (our modern s) was used everywhere else. Just had to geek about that for a minute.)

From these uses, it seems that Home Wood refers to the main, or Great, wood on a property or estate belonging to a landed family. Since the families in the above examples took their name from the wood, it stands to reason the wood was probably only referred to as the Home Wood by the family, or by members of the immediate community.

After all that, it seems that I was pretty well correct in my inferences, and I think I am safe to use Home Wood just as Georgette Heyer did.

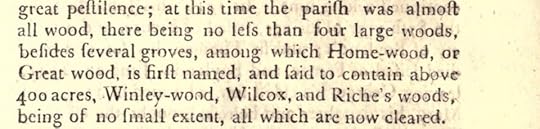

Just for interest’s sake, I’ll include one more less helpful but still relevant use of home wood that I found via Hathi Trust (remember I love Hathi Trust):

General Report of the Agricultural State, etc. of Scotland, Rt. Hon. Sir John Sinclair, bart., v. 1, appendix

General Report of the Agricultural State, etc. of Scotland, Rt. Hon. Sir John Sinclair, bart., v. 1, appendixAs one can see, this reference pertains to local wood that was preferred in the making of barrels for fish. While the connection here is slender at best, I still believe it pertinent, as “local” has the same connotation as “close” or “surrounding” in the example of Home Counties.

So, ye British, laugh me to scorn if you’d like, but since none of you saw fit to grace the internet or any reference books with an attestation to the fact that Home Wood is an accepted phrase, and how exactly it is to be used, I am forced to figure it out to the best of my poor ability.

And I think I did pretty good.

January 13, 2020

Demystifying Japan

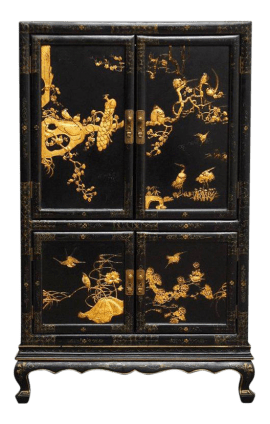

On Chairish.com

On Chairish.comIn Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, the heroine, Catherine Morland, is intrigued by a mysterious cabinet in her room at the Tilney’s home. She describes it as, “black and yellow Japan of the handsomest kind,” which begs the question, what is “Japan”?

Now, I kind of already knew the answer to this question, but it was cool to discover that 1) I was basically right, and 2) I had no idea what real “Japan” was.

So, 1) I somehow knew that “Japan” was a reference to lacquerware, and I had a vague picture of a plain black cabinet, painted with yellow or gold Japanese designs, like you’d see on an old mural or something, and then shellacked. Because that’s what lacquer is, right?

Well, 2) wrong. True lacquerware is made by painting wood or paper pieces with several layers of the sap of the lac tree, which grows only in Asia, and is poisonous until it dries. This last fact was probably why only master craftsmen undertook the art of lacquerware making, and, combined with the other two facts, made the finished pieces highly sought-after and very expensive (hence, they were only to be found in fancy places like Northanger Abbey).

Though the art of lacquerware-making probably originated in China, the Japanese and others created their own versions of the process, and all lacquerware became very popular in the West in the 18th century, when Europeans colonized areas of Asia (which the English rather high-handedly called the East Indies) and set up regular trade. Notwithstanding the fact that China and other Asian countries were still creating lacquerware,

In the West, lacquerware was often called “Japan,” showing that lacquerware-making is an Asian art.

Akio Haino, Department of Fine Arts, Kyoto National Museum

Lacquerware takes many forms, including intricate serving pieces, where hundreds of layers of lacquer are applied and then painstakingly carved (this is the original Chinese method of lacquerware-making):

Carved Cinnabar Lacquer Tray

Carved Cinnabar Lacquer Traywith Blue Magpies and Camellias

China, Yuan Dynasty (14th century)

Diameter 32.4cm, height 3.5 cm

Important Cultural Property (Korin-in Temple, Kyoto)

to detailed screens made with fewer layers of pigmented and etched lacquer (the original Japanese method), to shaped pieces, including cups, pots, bowls, trays, and boxes, made with a base of paper or thin wood and painted with several layers of pigmented lacquer, and often finished with gold:

I. M. CHAIT AUCTIONS, Beverly Hills, CA, USA

I. M. CHAIT AUCTIONS, Beverly Hills, CA, USABut what caught Miss Morland’s fancy in the guestroom of Northanger Abbey was probably something like the picture at the top of this post.

Which leaves one to wonder, did she have any idea the history of the handsome Japan cabinet she was inspecting? Because if she did, perhaps she would have spent less time searching its recesses for the lost manuscript of a tortured soul, and more time being amazed at the sheer artistry of the thing!

But such a pedantic consideration is probably too much to be hoped for in a heroine of Catherine Morland’s romantic stamp. And it would have ruined the story, too.