Judith Hale Everett's Blog, page 2

August 29, 2021

The Glory of Britain

During the Regency, the royal family enjoyed a love-hate relationship with their subjects. The British had (and still seem to have) an ingrained respect and devotion to their monarchs, but the madness of their king and the extravagance of the royal princes was too much even for their loyal subjects to stomach at times. The Prince Regent, who would later become King George IV, was gross and fat, had many lovers (and a mistress with whom he fathered eight children), and spent money like water on fantastic buildings to support his excessive lifestyle. He was often caricatured as a whale (a play on his being the Prince of Wales) in the company of buxom and half-dressed females, with Parliament running around him wagging fingers and crying over bills. Since his income came almost entirely from taxation, he was not a great favorite.

So it was not surprising that his heir, the Princess Charlotte, should be beloved by the people, because they saw her as the redemption of their beloved monarchy–the antithesis of her profligate father and the hope of a return to virtue. Females were regarded as the guardians of virtue during the Regency, and when Prince George and his estranged wife Caroline were unable to produce a male heir, it was seen as divine intervention.

Princess Charlotte of Wales c. 1817

Princess Charlotte of Wales c. 1817Charlotte could very well have turned out to be a disappointment, because her childhood was one of upheaval and neglect by her parents. They gave her every advantage of a royal child, but not their individual attention or love. Any time she spent with either parent was more often used for fuel in their never-ending feud than as bonding time. Luckily, she had loving and indulgent governesses who treated her like their own child, and she grew to be a happy child with a sunny disposition–her only unconformity was a tendency toward tom-boyishness.

As she grew older, her demeanor shifted to a casualness that offended her high-minded relatives, including her father, who forgot his own rebellious teens (and twenties, and thirties, and…) and clamped down on her. His strictures included reduced pin money, early bedtimes, and eventual isolation at Windsor castle with only her maiden aunts for companionship. The princess, of course, rebelled at this, entering into secret trysts with practically any male she found interesting within her circle (mostly cousins). She formed a passion first for her illegitimate cousin George FitzClarence, then for another illegitimate cousin Charles Hesse, both of which relationships were encouraged by her mother, Princess Caroline, but which both ended at the young men being called away to fight on the Continent.

Hoping to curb her, Prince George (now Prince Regent) arranged a marriage for her with William, Prince of Orange, whom she did not like very much. After much manipulation, coercion, and outright begging, Charlotte at last agreed to sign the marriage agreement, but almost immediately became besotted with a Prussian prince (it is unknown which one), before falling in love with Leopold Saxe-Coburg, a dashing Belgian army lieutenant general. The youngest son of a Duke, Leopold had little to offer by way of wealth, but his distinguished military career and high birth helped at last to change the Prince Regent’s mind. In March 1816, their engagement was announced, and they were married May 2, to the exuberant joy of the British people. So many crowded the streets on the wedding day that the royal couple had difficulty travelling.

Charlotte and Leopold were very happy together, and her teenage wildness quickly disappeared. She described Leopold as the “perfection of a lover,” and he commented that, “we were together always, and we could be together, we did not tire.” The British subjects greeted the couple with wild applause whenever they were seen in public, and often sang “God Save the King” to them.

After suffering a miscarriage in early 1817, Charlotte became pregnant again, but instead of being attended by a physician, the modish Sir Richard Croft saw to her care, and put her on a strict diet accompanied by bleedings. She was weakened considerably by this treatment, and had a terribly rough delivery. A physician was called to use forceps, which may have saved both the child and the princess, but Croft would not let him see the princess. The baby was stillborn and Charlotte bled severely, dying hours later.

Her death sent the entire country into deep mourning for two weeks–the British people felt as though their future had been taken from them. Linen drapers ran out of black cloth, and even gambling dens shut down on the day of her funeral as a mark of respect. The Prince Regent was so grief-stricken he could not attend the funeral, and Leopold never quite recovered, as if he had lost his heart. He did not remarry until 1832, only when he was made King of the Belgians.

August 20, 2021

Dear reader: a gossip’s tale

This week I did a guest post for the Bluestocking Belles’ Teatime Tattler, a historical romance blog masquerading as a gossip rag. The idea is to insert yourself into your latest book as a Quiz (a gossip) who reports their observations in the society journal. It was absolutely perfect for Romance of the Ruin, as the hero finds himself beset by vicious rumors regarding his legitimacy as lord of the manor (you have to read it to find out if they are true or not).

The Lecture by Vittorio Reggianini

The Lecture by Vittorio ReggianiniDearest Reader:

The arrival of another country heiress in the Metropolis is hardly cause for excitement, at least in our considered opinion, for they are two a penny, if you will pardon the pun. That these all-too-often underbred innocents are beset by suitors will amaze no one, for there are at least as many gentlemen with fortunes needing to be mended, and they are none of them nice in their requirements. Let her be well endowed in the stocks, and her other charms—or lack thereof—need not signify.

The particular country heiress who has excited the latest rage, a Miss Lenora Breckinridge, while possessing somewhat more by way of refinement than her contemporaries, appears quite as susceptible to flattering attentions, and may require a hint. She has made no secret of her admiration for a certain gentleman, and is forever being seen with him, at Society parties and driving about town, and has raised both eyebrows and concerns. One can only wonder at her parents for neglecting to advise her in this matter, for they surely must be privy to the rumors which blaze through the town regarding her beau, and if she cares not to safeguard her fortune, her father at least should.

For the man whom our young lady has singled out is none other than the mysterious Lord Helden, whom we do not scruple to style a fortune hunter—though this may be the least of his sins. It is commonly known that his estate is ruined, its bounties wasted by his predecessor for reasons too sordid even for our pen, and he can offer not even a sound roof over the head of his future bride.

But even more shocking, if rumors are to be believed, his lordship may prove to be nothing more than an imposter. The thought makes one stare! However, upon reflection, one will acknowledge that for the lost heir to a viscountcy to suddenly reappear just as an heiress has made no secret of her admiration for his estate, is a fact that must bear more scrutiny than Miss Breckinridge, or her parents, appear to deem necessary.

The near impossibility that anyone but his lordship could prove himself to be Lord Helden, we cannot but allow; however, creditable sources have confirmed that the man claiming to be Lord Helden has been, for the past six months, performing the duties of caretaker to the Helden estate; moreover, he did not show himself to Society in his present guise until after Miss Breckinridge came upon the scene. If this does not arouse suspicion, we know not what could, and we call upon those in positions of responsibility to more seriously consider the matter.

One shudders to reflect upon the depravity of a man who will stop at nothing, be it the entrapment of an innocent maiden or the heinous sin of impersonating a nobleman, to gain a fortune. While such cannot be proven against the man in question at this time, this observer holds it as the duty of all loyal citizens to be vigilant against the mere possibility of evil. At the very least, if neither Miss Breckinridge nor her parents choose to alter her course, and she bestows her hand and fortune upon this Lord Helden, they only will be to blame when his true character is unfolded, as it must certainly be, in their married life. We have done our poor best to undeceive her, and can only hope that our friendly hint will be heeded before it is too late.

–a Disinterested Observer

August 13, 2021

Finding Connections

Have you ever been to a place, or seen a picture or heard a description of a place, that you just yearned to belong to? This happens to me all the time when I’m reading Regency romance. Whether it’s Jane Austen’s descriptions of the English countryside, or Georgette Heyer’s enumerations of the beauties of a London townhome, I wish I could claim some sort of belonging to these places.

As an American writing English romances, I often feel like a great pretender. No matter how often I visit England, or study its dialects, or research its history, I will never have that native comfort of knowing that what I say is true to reality. There will always be a worry of whether I got it right, or whether someone who actually knows better will call me out.

But my dear husband, who is a genealogist, was able to point out to me that I have a connection to the Regency that is just as close as a native Brit’s: my ancestry is overwhelmingly British, and my predecessors were tramping the very same lanes and rubbing shoulders with the very same crowds that I love to read about in historical fiction. Lest I get too highbrow about it, however, I must admit that my ancestors were hardly of the upper 10,000.

One ancestor I discovered to be a potman at the Bricklayer’s Arms in 1811. A little extra research divulged the information that a potman was simply a server, usually of drinks, but of anything else that was ordered. The Bricklayer’s Arms I assumed to be some sort of pub or inn, so I turned to my copy of the 1815 Epicure’s Almanac, which is a listing of all the eating establishments of any note in all of London at the time. There I found that the Bricklayer’s Arms was a major coach stop, and offered “a most comfortable repast either in the style of a hasty dinner or a flying lunch.” This was interesting enough, but imagine my excitement when I was able to find this posting inn actually listed on Horwood’s 1813 map of London, on the corner of the Kent Road and Bermondsey New Road. The Bricklayer’s Arms is no longer extant, having been replaced by houses, but it was such a thrill finding this connection that I just had to use it in the opening scene of Romance of the Ruin, Book 2 of the Branwell Chronicles.

Another ancestor was a coal merchant in Bath during the Regency, driving his coal cart up and down all those hills and shoveling coal into the coal chutes that can still be seen beneath the flagstones. Sadly, a newspaper article in the 1856 Bath Chronicle describes his death after his cart was overturned. But his son had risen to be a policeman, and lived on Henrietta Street, just around the corner from where Jane Austen’s family had lived.

10 Henrietta Street, Bath, UK

10 Henrietta Street, Bath, UKAs I found the stories behind these names on birth certificates and censuses, they came alive to me, much as the characters in historical novels come alive with their stories. Telling stories is a way to connect us, not only to each other, but to those who came before. I’m proud of my English heritage, even and especially because it was not nobility or gentry, but hardworking people who did their best with what they had, and bettered themselves when they could. That’s the kind of nobility I can really get behind.

August 3, 2021

Romance of the Ruin Available 8/4/21

I am more pleased than you know to announce that Romance of the Ruin, the second book in the Branwell Chronicles series, will be available in print and ebook formats tomorrow, August 4, on Amazon. Apple Books, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, and all other platforms will have it available next week.

Thanks for your patience as this took me two months longer than I had anticipated; I hope you will feel it was worth the wait!

Prey to Gothic sensibilities, Miss Lenora Breckinridge is smitten with the air of tragedy and romance surrounding an abandoned mansion. Convinced that she is fated to become its mistress, she sets out to find the master, secure in the belief that he will fall madly in love with her and they will use her fortune to restore the manor together.

Mr. James Ingles is disillusioned by the short hand fate has continually dealt him, but goes to be caretaker to the ruined mansion in a last effort to seek his fortune. When he discovers Miss Breckinridge’s fascination with the ruin, however, he recognizes an opportunity to change his fate, if only he can put his plan in motion.

July 8, 2021

Congratulations to the Winners!

Congratulations to the winners of my Two in the Bush audiobook swag pack giveaway!

Laurel WhitneyDragonladee1005Emily SchultzMarintha HaleTeresa Wetherell NewmanI had such a great response that I decided to do two bonus winners who will receive an audiobook download code:

Ronda CookseyAnastasia KatopodisWinners, please email me at news@judithhaleeverett.com or direct message me on Facebook to give me the address where I should send your prize (remember, if you are outside the US I can only give you the audiobook download code). Bonus winners, I just need your email address.

Thank you for being such great fans!

June 28, 2021

The Giveaway is Live!

The time has come! Enter now to win one of five Two in the Bush audiobook prize packs!

(tablet not included in giveaway)

(tablet not included in giveaway)Click here for all the details and to enter: Enter the Giveaway!

June 24, 2021

Audiobook Giveaway!

To thank you all for being such great fans, I’m hosting a giveaway for my audiobook this coming week! Five lucky winners will get everything they need to curl up and relax with their favorite tea or hot cocoa to the delightful tones of Clare Wille reading Two in the Bush.

The giveaway starts Monday, June 28, and will be open to entries until Monday, July 5. Check back for details on how to enter!

Each prize pack (valued at $50) will include:

A Two in the Bush audiobook download codeA limited edition Two in the Bush mugA sample size English Tea Shop herbal teaA sample size Stephen’s hot cocoaDue to high (actually, outrageous!) shipping costs, I can only offer the full giveaway to US residents. If someone from outside the US enters and wins, they will still receive the audiobook download code (which is the best part!) but not the physical items.

If you know anyone who may be interested in entering the giveaway, please feel free to share this post. If they like my Facebook page, they will be notified of the giveaway when it starts.

Thanks again for your amazing support!

June 17, 2021

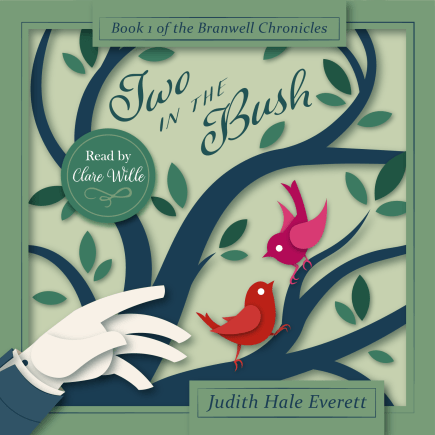

Two in the Bush Audiobook Coming Soon!

For all of you who have read Two in the Bush, thank you! Your support has been wonderful! It’s hard to even put into words how much it means to me that so many of you took a chance on me as a new author.

If you haven’t had the chance to read it yet, you’re in luck! The Two in the Bush e-book is on sale now through June 24th for only US $1.99, so grab it while it’s hot!

Search for it on you favorite retailer, or click on one of these buy links:

Reviews for Two in the Bush have been overwhelmingly positive! Here are a few:

Reviews for Two in the Bush have been overwhelmingly positive! Here are a few:The enthusiasm for Two in the Bush is well-deserved, as it is a delightful story!

Two in the Bush is a fabulous frolic through Regency-era England unrivaled by any other author I’ve read (save perhaps Heyer herself).

Read it in three days!

I consider myself a pretty harsh critic and had given up on the genre. Instead I found myself reading and really enjoying. Hoping for lots more from this excellent author!

It has also received some great editorial reviews:I love this book!!! It is full of wit and humor, drama and intrigue with a wonderfully unique twist at the end.

An original, eloquently entertaining, and deftly crafted Regency Romance novel by an author with a clear mastery of the genre, “Two in the Bush” by Judith Hale Everett is an extraordinary and unreservedly recommended addition to community library Historical Romance Fiction collections.

Midwest Book Review

And now for the big announcment:Two in the Bush is a series of follies and foibles, fun, and some very witty dialogue. It is also jam packed with many Town delights including Vauxhall, Almack’s, the theatre, and shopping…well researched and seamless in description and usage. I could tell the author did a lot of research to understand all the locations (rather than just name dropping) and really provided a great sense of what those experiences may have been like.

Anne Glover, Regency Reader

I have contracted with the incredibly talented to narrate the audiobook for Two in the Bush. Ms. Wille is a veteran actor on stage, screen, and voiceover, and is one of my favorite narrators of Georgette Heyer’s books. Her grasp of the humorous nuances of Heyer’s writing is excellent, and I’m so excited to hear her interpretation of Two in the Bush!

The expected release date for the audiobook is July 1! It will be available on all platforms, including Audible and Apple Books. I also intend to make it available in libraries, so if you love to borrow audiobooks from your local library, get set to request it from them!

(And just a little hint: if you think you might want to purchase it, just wait a bit, and you might see it go on sale)

Again, thank you so much for your continued support! I love my readers!June 2, 2021

Physician, Surgeon, or Apothecary?

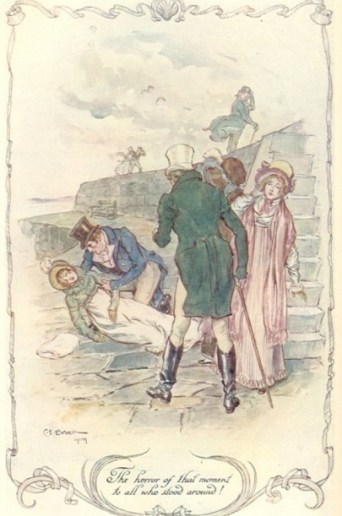

“A surgeon!” said Anne.

He caught the word: it seemed to rouse him at once; and saying only: “True, true, a surgeon this instant,” was darting away, when Anne eagerly suggested:

“Captain Benwick, would not it be better for Captain Benwick? He knows where a surgeon is to be found.”

Persuasion by Jane Austen, p. 50

If you’ve read this book, or seen the excellent adaptation starring Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds, you’ll recognize this scene as the one in which Louisa Musgrove has fallen and hit her head, and been rendered unconscious. Now, today, if this were to happen, none of us would call for a surgeon, because surgery is something that takes place in a hospital and involves cutting and stitching together again and, especially in the case of head injury, is hopefully the last resort to recovery.

However, in Jane Austen’s day, “surgeon” was what people called a general practice doctor, who might also be the apothecary, depending on the size of the town or the availability of medical professionals in the area. A surgeon in the Regency era was simply a self-taught or non-degree-holding medical man who knew enough to treat you when you were ill, and would also perform surgery if necessary.

Medicine has always been an evolving art, and its designations have necessarily evolved with it. As early as the 16th century, England had organized medicine into what was called a tripartite system, with strict definitions of each of the three recognized areas of medicine.

The apothecaries were chemists, who concocted drugs or medicines for people to take when ill. They were learned in use of herbs and plants as well as various minerals and chemicals, and were primarily concerned with correctly mixing medicines and selling their wares, not advising customers on how to treat illnesses (very much like modern-day pharmacists).

Physicians were perhaps the “highest” of the three divisions, simply because they had the most formal education and catered almost exclusively to the wealthy. To become a physician, one had to receive a degree in medicine from a recognized institution, like Oxford or Cambridge. A physician would diagnose, treat, and advise patients regarding their maladies, and would prescribe medications.

Surgeons were a bit more complicated. They performed any invasive treatment (surgery), including amputation and bloodletting, but also cutting hair. The Guild of Surgeons was officially combined with the Company of Barbers during the reign of King Henry VIII, perhaps because there wasn’t enough work for two separate men in every town, or because people who like to cut things ought to be contained—who knows? But barber-surgeons were common for a long while.

During the 18th century, however, the boundaries between these three designations began to be blurred, mostly because there weren’t enough physicians to go around, and even if there were, the poor could not afford them. Surgeons and apothecaries began to step into the gap, using their applied experience in working beside physicians to advise and treat any who needed their help.

The Apothecaries’ act, 1815: A Reinterpretation, by S.W.F. Holloway, p. 1

The Apothecaries’ act, 1815: A Reinterpretation, by S.W.F. Holloway, p. 1By the time of the Regency, the surgeon-apothecary had become common, performing surgeries alongside treating illnesses and prescribing drugs, but they at least generally became licensed through the College of Surgeons in order to do so. A new group called chemists managed the compounding of the drugs to be dispensed, while physicians still were the acknowledged gods of medicine, but simply were not a practical solution to the general populace.

The Apothecaries’ Act of 1815 officially regulated the practice of apothecary-surgeons, requiring a 5-year apprenticeship and an examination before candidates would be permitted to hang up their shingle. It is hoped that this increase in education and experience made a difference, as the reigning medical theory—of the need to bring the body into balance by stimulant or depressant use—was not much of an improvement from that of the middle ages.

Incidentally, or logically, because of the distinction of education, only physicians were referred to as Doctor So-and-so, while apothecaries and surgeons were merely Mister.

Resources:https://collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/exhibits/show/apothecary-jars/sequence

THE APOTHECARIES’ ACT, 1815: A REINTERPRETATION by S. W. F. HOLLOWAY

May 26, 2021

A Debate Over Debutantes

As a word geek, I do apologize for splitting hairs, but I really must take a stand: there were no debutantes in the Regency.

Ok, let me clarify: during the years 1800-1830 there were young ladies who were referred to as debutantes, but never in the way we have come to know the word. The word “debutante” is a French word meaning “lady beginner,” and was almost universally applied to new actresses until around 1830, when it began to bleed over into society.

But it still didn’t mean what we think it means (darn right, Inigo). The word “debutante,” when not used to describe a new actress—as it continued to be through the end of the century—was used as a term of derision, to describe a woman new to society who either did not know how to act, or who knew so well how to act that she might as well have been on the stage.

It was not until the 1840’s that the term took on the meaning we know today, of a young woman just coming out into society.

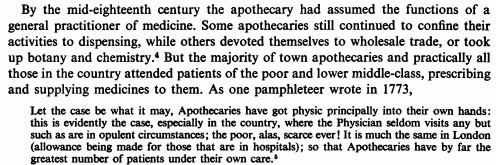

How dare I claim this? Well, for one thing, I have never come across the word “debutante” used in its modern sense in the novels that were actually written during the Regency. This made me question whether the word as we know it was in use back then. So I turned to the Hathi Trust, an awesome online resource that takes digitized works (millions of them) and makes them available to search. Their Bookworm tool allows you to search for a specific word (or even two words to compare) and charts the results by number of hits and date. Awesome, huh? Here’s the result for “debutante” between 1801-1900:

So if you just went from this, you’d think, “Oh! Debutante was totally in use in the Regency! I can go ahead and use it with impunity in my Regency romances!”

You would, however, be wrong. Because the next cool thing about Bookworm is that you can click anywhere along the graph line and it brings up a list of the works wherein the searched word appears. Then you can go directly to that work and see how the word is used. In this case, it would show you things like this:

From The Satirist 1814, p. 95

From The Satirist 1814, p. 95 The Monthly Mirror 1818, p. 158

The Monthly Mirror 1818, p. 158 Ladies Monthly Museum 1820, p. 185

Ladies Monthly Museum 1820, p. 185And then, in the 1820’s, there are these:

Taken from a scene where a society woman tried to use her influence inappropriately; A Letter From the King to His People 1821, p. 47

Taken from a scene where a society woman tried to use her influence inappropriately; A Letter From the King to His People 1821, p. 47 Description of a society man’s listening prowess; Pen Owen 1822, p. 292

Description of a society man’s listening prowess; Pen Owen 1822, p. 292You can see that the first three uses of the word are clearly applied to actresses, and the last two illustrate the derisive use of the word beginning in the 1820’s (though, I’d argue that the last one is actually describing an actress because of “her lovers,” which unmarried ladies of quality were never supposed to have, while women who had taken to the boards were fair game).

When we search “debutante” in the 1830’s, we start to see a shift, very possibly from the influence of the U. S., which seems, from the following, to have fully embraced the modern meaning of the word:

“How to Illustrate for Money,” Redbook, New York, 1836 p. 43

“How to Illustrate for Money,” Redbook, New York, 1836 p. 43Redbook was distributed in London, and may have contributed to the gradual acceptance there of the word “debutante” to mean a young girl coming out into society. But it was a long haul. Note the derisive tone of the following description using the word in a London publication of the same year:

The New Belle Assemblee 1836, p. 153

The New Belle Assemblee 1836, p. 153“Debutante” was not generally positively used in society until at least 1840, which is well out of the Regency proper, and only at the tail-end of the extended Regency. Even the word “debut” was more often applied to the stage or the ring than to society. The terms most often used were “appearance” or “come out” to describe the fact of a young lady’s entering society, and “out” or “in her first season” to describe the girl’s social state.

“…supposing Fanny was now preparing for her appearance, as of course she would come out when her cousin was married.”

Mansfield Park, Jane Austen, p. 153

“She has never been presented yet, so she is not come out, you know; but she’s to come out next year.”

Cecilia, Fanny Burney, v. 2 p. 149

Pin up the Train, Hugh Thompson

Pin up the Train, Hugh ThompsonAdmittedly, it is quite a mouthful to have to say “the young lady who was making her come out” rather than “the debutante,” or “the other young ladies in their first season” rather than “the other debutantes,” but they liked to use more words during the Regency anyway, so it’s just more historically accurate to do the same, right?

Oh, boy. I could go on about that, too, but that’s a post for another day.