Judith Hale Everett's Blog, page 3

May 19, 2021

Where Has All the Civility Gone?

One of the truest signs of maturity is the ability to disagree with someone while still remaining respectful.

Dave Willis

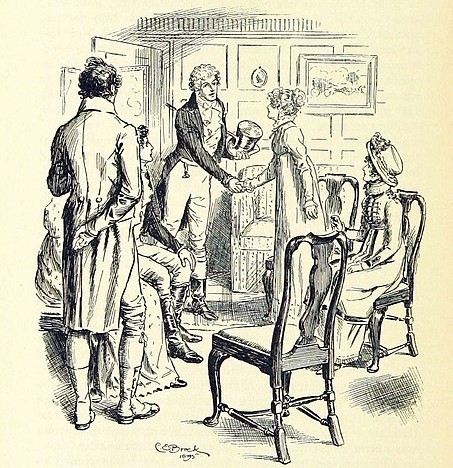

The Gallant Suitor, by Edmund Blair Leighton

The Gallant Suitor, by Edmund Blair LeightonI think it’s sad that a man nowadays has to think twice before opening a door for a woman. The poor guy just wants to be nice but he also doesn’t want to make her feel less than she is, and society has taught him to fear that the act of opening a door might make her think he thinks she’s too weak to do it herself. So he either dithers for a bit and misses the chance—because she has been taught that if she doesn’t assert herself then she will be thought to be weak, and therefore opens the door herself—or risks reputation and possibly limb and opens the door for her.

I make sure to warmly thank anyone—male or female, adult or child—who opens a door for me, even if I was fully capable of doing it myself, because I choose to believe that they simply want to make my day a little smoother and a little brighter.

How unfair is it that we’ve made it so hard to show civility? What do we think we can accomplish by stamping out this centuries-old virtue? Recent events have proven that without civility, we become inflamed and divided, and then we are nothing but weak. It’s very sad, because civility is such a simple thing. It is simple, and yet it takes self-control and determination; it is hard, and we’ve become a society that thinks it does not need to do hard things.

One of the great portrayals in historical literature of the ability to conduct oneself civilly is in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, when Fantine verbally abuses and spits on Jean Valjean, whose reaction is to calmly wipe the spittle from his face and request her release from jail. Now, these were two good people in extraordinary circumstances, but I would argue that ninety percent of all disagreements, heated or otherwise, are between good people who otherwise would be perfectly able to act with civility were they not under the influence of some worry or stress or pain. All that is missing is the determination to treat others as you want to be treated—to see humanity in your opponent despite the challenges you, personally, are experiencing, and to rise above yourself to make the situation better.

This little piece of the puzzle—civility—is not weakness, as some people have claimed. It is when we go without civility that we are weak. Without civility, people grow lazy in their own selfishness and cease to strive for the common good. Without civility, whole societies fracture and fall, and humanity suffers. Civility is an atmosphere that shields us from our own destructive influences, making us strong.

We simply cannot close our eyes to the need for civility.

May 12, 2021

The Essential Introduction

Nowadays we don’t think an introduction is a big deal. We introduce ourselves whenever we feel the need to, or carry on whole conversations without even finding out the name of the other person. But during the Regency, introductions were essential. The right introductions were the key to success in society, and the wrong ones spelled certain doom.

So much depended on who you knew in the Regency period that people took their introductions very seriously. There were all sorts of rules about how to be introduced, and by whom, that it’s a little mind-boggling for us modern people. For instance, a person of higher rank was never introduced to a person of lower rank–it was the other way around. That way the higher-ranking person had the privilege of declining the introduction if they felt it to be inappropriate. Likewise, a man never introduced himself to a woman, but was introduced through a suitable mediator–a mutual acquaintance or hostess, or in the case of an assembly room, the patroness or master of ceremonies. And even then, the man was introduced to the lady, who could refuse to acknowledge him if she did not wish the relationship.

In Pride and Prejudice, when Mr. Bingley moved into the neighborhood, Mrs. Bennet lamented that if Mr. Bennet did not visit Mr. Bingley–which implied that he would then introduce him to his family–she would be forced to rely upon her neighbor for an introduction for her girls, but “‘I do not believe Mrs. Long will do any such thing. She has two nieces of her own. She is a selfish, hypocritical woman, and I have no opinion of her.'” Thus, an introduction could be used as a sort of bargaining chip, or as a weapon to keep others from a certain social circle.

When you recognize the rigid rules surrounding introductions, it becomes easier to understand how Mr. Darcy could wander around the assembly room the entire evening without having someone try to introduce him. Mr. Bingley, as his friend and thus his social equal, was the only person suitable to introduce him, and Mr. Darcy declined his invitation to be introduced. So no one dared to approach him, and he was free to “(walk) here and (walk) there, fancying himself so very great!”

Perhaps one important nuance to this whole introduction thing is the safety it gave to women. They were almost always in control of whom they allowed into their social circle, and therefore could avoid friendships or acquaintanceships with gentlemen whom they believed to be unsavory. About the only time a woman would be introduced to a man was was when he was significantly older than she was, and somewhat close in relationship–say, the father of a friend–so the privilege would be given to the elder. But in that case, he was not likely to be in any way dangerous to her, and she need not worry about accepting the relationship.

Of course, this can all break down, and did, certainly, causing problems and mishaps and discomfort to countless parties. But good or bad, it makes for a great plot device in historical novels–and we can read and enjoy because we don’t have to deal with all those rules, or their consequences, anymore!

Resources:see Rachel Knowles’ excellent article on introductions here

May 3, 2021

How Bazaar

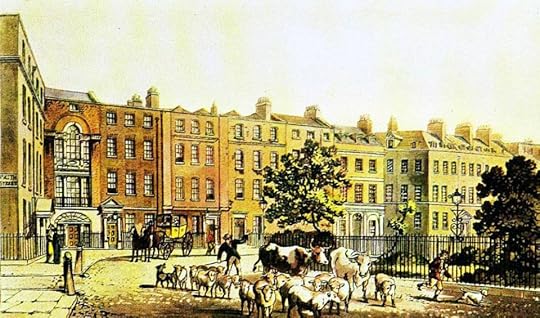

Soho Square, 1820

Soho Square, 1820Anyone who is familiar with Regency romance will recognize the name “Pantheon Bazaar.” This location was used several times in Georgette Heyer’s works, and subsequently in the works of hundreds of her contemporaries. Unfortunately, Georgette got it wrong; the Pantheon was not a bazaar until 1834, well after the time period about which she was writing. And since she was the Queen of Regency romance, everyone just followed suit.

Setting aside the fact that she did not have the internet, or access to half the number of historical documents we have today, it is easy to see why she could be confused. The Pantheon was a destination for members of London society from its inception in 1772, and from a clause in the deeds, it retained its name no matter what its purpose (even now, though the building houses Marks & Spencer, it still has the name “Pantheon” over its door). Built by James Wyatt to house the “nocturnal adventures of the British Aristocracy,” it was a hot spot for balls and masquerades for almost three decades.

Two separate fires, resulting in expensive restoration projects, endangered its financial viability, however, and in 1811, its popularity had declined so far that it was sold to the National Institute to Improve the Manufactures of the United Kingdom (don’t you love the awesome names these old societies gave themselves? I wonder if they went by NIIMUK.). After a complete renovation, after which it was still called the Pantheon, it enjoyed three years as a theater and opera house, but simply couldn’t come up to snuff. The building was abandoned, the innards sold to pay off creditors, and it stood empty until 1831, when it was finally purchased and remodeled over the next three years into the Pantheon Bazaar.

The Pantheon Bazaar was not the first of its kind, by a long shot. The Exeter Change, which was built during the reign of Charles II, is often referenced in historical fiction for its menagerie, which boasted several wild animals and birds, as well as colorful performers. But the Change also housed “shops being furnished with such articles as might tempt an idler, or remind a passenger of his wants,” according to Robert Southey in 1807.

The Change does not seem to have had much competition until 1816, when the Soho Bazaar, occupying three adjacent buildings in Soho Square, was opened by Mr. John Trotter. The warehouse was donated “to encourage female and domestic industry,” with the more specific purpose of providing an inexpensive venue for those adversely affected by the Napoleonic Wars to make a living by selling such useful articles as could be made by hand at home. The business was excellently and fairly managed, and prices were set competitively enough that no bargaining was allowed. This bazaar enjoyed incredible popularity, its square often blocked by three rows of carriages waiting for their owners to finish their shopping, until it finally closed in 1885.

It seems fair to assume that the Soho Bazaar was most likely the shopping place Georgette Heyer meant in her excellent novels, but who can blame her for getting confused? I certainly don’t dare.

References:Shops and Shopping: 1800-1904, by Alison Adburgham, Barrie and Jenkins, 1989.

Regency Hot Spots: Soho Square Bazaar

February 23, 2021

A Fair Funambulist

Many of us think of the Regency era as being very proper, with well-bred people traipsing about in orderly groups and participating in elegant activities. This was true, but only to a point. Alongside those gently-bred ladies and men lived a host of colorful characters. The Prince Regent himself was no small personality, with his ever-enlarging girth and constant demands on the Treasury—but that’s a post for another day.

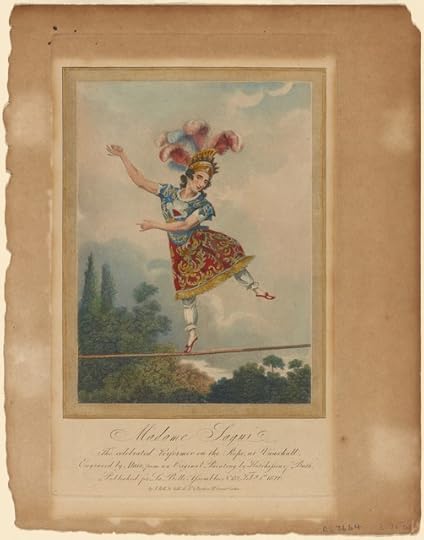

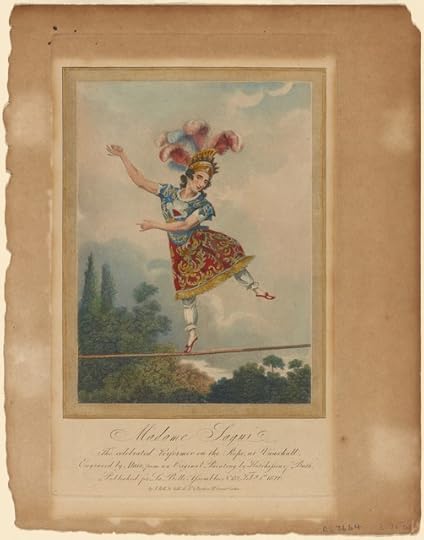

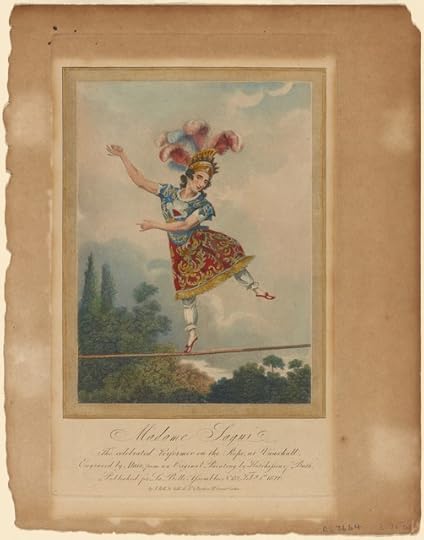

One of the colorful personalities that is hardly mentioned in modern literature, but who undoubtedly was known by name to almost all the members of the Regency ton, was Madame Saqui, a tightrope walker and gymnast. Saqui’s feats of agility stunned and amazed audiences for nearly 30 years—her last performance was at the age of 69.

Described as “a short, thin, wiry little woman,” Saqui did not fit into the established ideal of femininity, and sometimes received rather rude press regarding her “deformed” body. This didn’t seem to faze her, however, probably because she knew very well that her body was the perfect build for acrobatics.

Saqui’s crowds of fans didn’t seem to care what she looked like—they only cared that she could do amazing things on a tightrope, with fireworks whizzing around her. She regularly sold out shows at Covent Garden, played to packed crowds at Vauxhall Gardens, and was the headliner at the Prince Regent’s birthday party.

Madame Saqui’s career started when she appeared in Paris just in time to see the reigning tightrope walker, Tivoli, fall from his rope. Seeing that he could not go back on, Saqui instantly took his place, and basically took over for him. She captivated French audiences year after year, and her fame became such that Napoleon chose her to ignite the fireworks that welcomed his bride into Paris.

After the fall of Napoleon, Saqui took rather a brazen step and came to England, but despite the prevailing anti-French feeling, she was an instant success. One of her first performances was called “a terrifically grand spectacle” by an onlooker, and Saqui the “heroine of the piece.”

Saqui’s style was what set her apart. It was described as “fantastic rather than graceful, abrupt and fearless, striking by its originality rather than charming by its elegance.” She wore flamboyant costumes and tall headdresses that captured the eye and interest. Rather than adopting the slow and ballet-like movements of other tightrope artists of the time, Saqui chose to display her athleticism with quick, energetic routines, often with an element of surprise. She acted out famous battles on a horizontal rope, or charged up a nearly vertical one into a blaze of fireworks, or dropped from the sky, as if from nowhere.

There was one moment in her sparkling career where Saqui fell from favor. She was so beloved of Napoleon that she became overconfident and daringly placed an eagle—his symbol—on her carriage. She rode in this carriage triumphantly around France, performing for troops between battles in the Peninsular war, until the eagle was noticed by an official. Napoleon ordered her to remove it, and Saqui, humiliated by his rejection, went into a sort of self-exile. But then the Emperor was defeated only a few years later, and she was forced to find a new patron anyway.

To all appearances, this hiccup didn’t harm her much. Her career in England rivaled her success in France, and she was never out of work or low on praise until she retired from public performances in 1845. Even then, a theater she had opened with her husband continued to bring her fame until Messr. Saqui died, and his brother wasted all the profits on fantastic and ridiculous schemes that all failed.

Poor Madame Saqui grew bitter and pompous in her old age, reliving every golden moment to spite everyone around her. She was, to use a worn-out phrase, a fallen star, born to shine brightly and to dim into obscurity. But her legacy lived on in many subsequent fearless and enterprising funambulists (yes, that’s a real word, and it means “fun to walk”—just kidding, it means tightrope walker).

It’s Fun to Funambulate

Many of us think of the Regency era as being very proper, with well-bred people traipsing about in orderly groups and participating in elegant activities. This was true, but only to a point. Alongside those gently-bred ladies and men lived a host of colorful characters. The Prince Regent himself was no small personality, with his ever-enlarging girth and constant demands on the Treasury—but that’s a post for another day.

One of the colorful personalities that is hardly mentioned in modern literature, but who undoubtedly was known by name to almost all the members of the Regency ton, was Madame Saqui, a tightrope walker and gymnast. Saqui’s feats of agility stunned and amazed audiences for nearly 30 years—her last performance was at the age of 69.

Described as “a short, thin, wiry little woman,” Saqui did not fit into the established ideal of femininity, and sometimes received rather rude press regarding her “deformed” body. This didn’t seem to faze her, however, probably because she knew very well that her body was the perfect build for acrobatics.

Saqui’s crowds of fans didn’t seem to care what she looked like—they only cared that she could do amazing things on a tightrope, with fireworks whizzing around her. She regularly sold out shows at Covent Garden, played to packed crowds at Vauxhall Gardens, and was the headliner at the Prince Regent’s birthday party.

Madame Saqui’s career started when she appeared in Paris just in time to see the reigning tightrope walker, Tivoli, fall from his rope. Seeing that he could not go back on, Saqui instantly took his place, and basically took over for him. She captivated French audiences year after year, and her fame became such that Napoleon chose her to ignite the fireworks that welcomed his bride into Paris.

After the fall of Napoleon, Saqui took rather a brazen step and came to England, but despite the prevailing anti-French feeling, she was an instant success. One of her first performances was called “a terrifically grand spectacle” by an onlooker, and Saqui the “heroine of the piece.”

Saqui’s style was what set her apart. It was described as “fantastic rather than graceful, abrupt and fearless, striking by its originality rather than charming by its elegance.” She wore flamboyant costumes and tall headdresses that captured the eye and interest. Rather than adopting the slow and ballet-like movements of other tightrope artists of the time, Saqui chose to display her athleticism with quick, energetic routines, often with an element of surprise. She acted out famous battles on a horizontal rope, or charged up a nearly vertical one into a blaze of fireworks, or dropped from the sky, as if from nowhere.

There was one moment in her sparkling career where Saqui fell from favor. She was so beloved of Napoleon that she became overconfident and daringly placed an eagle—his symbol—on her carriage. She rode in this carriage triumphantly around France, performing for troops between battles in the Peninsular war, until the eagle was noticed by an official. Napoleon ordered her to remove it, and Saqui, humiliated by his rejection, went into a sort of self-exile. But then the Emperor was defeated only a few years later, and she was forced to find a new patron anyway.

To all appearances, this hiccup didn’t harm her much. Her career in England rivaled her success in France, and she was never out of work or low on praise until she retired from public performances in 1845. Even then, a theater she had opened with her husband continued to bring her fame until Messr. Saqui died, and his brother wasted all the profits on fantastic and ridiculous schemes that all failed.

Poor Madame Saqui grew bitter and pompous in her old age, reliving every golden moment to spite everyone around her. She was, to use a worn-out phrase, a fallen star, born to shine brightly and to dim into obscurity. But her legacy lived on in many subsequent fearless and enterprising funambulists (yes, that’s a real word, and it means “fun to walk”—just kidding, it means tightrope walker).

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Madame Saqui!

Many of us think of the Regency era as being very proper, with well-bred people traipsing about in orderly groups and participating in elegant activities. This was true, but only to a point. Alongside those gently-bred ladies and men lived a host of colorful characters. The Prince Regent himself was no small personality, with his ever-enlarging girth and constant demands on the Treasury—but that’s a post for another day.

One of the colorful personalities that is hardly mentioned in modern literature, but who undoubtedly was known by name to almost all the members of the Regency ton, was Madame Saqui, a tightrope walker and gymnast. Saqui’s feats of agility stunned and amazed audiences for nearly 30 years—her last performance was at the age of 69.

Described as “a short, thin, wiry little woman,” Saqui did not fit into the established ideal of femininity, and sometimes received rather rude press regarding her “deformed” body. This didn’t seem to faze her, however, probably because she knew very well that her body was the perfect build for acrobatics.

Saqui’s crowds of fans didn’t seem to care what she looked like—they only cared that she could do amazing things on a tightrope, with fireworks whizzing around her. She regularly sold out shows at Covent Garden, played to packed crowds at Vauxhall Gardens, and was the headliner at the Prince Regent’s birthday party.

Madame Saqui’s career started when she appeared in Paris just in time to see the reigning tightrope walker, Tivoli, fall from his rope. Seeing that he could not go back on, Saqui instantly took his place, and basically took over for him. She captivated French audiences year after year, and her fame became such that Napoleon chose her to ignite the fireworks that welcomed his bride into Paris.

After the fall of Napoleon, Saqui took rather a brazen step and came to England, but despite the prevailing anti-French feeling, she was an instant success. One of her first performances was called “a terrifically grand spectacle” by an onlooker, and Saqui the “heroine of the piece.”

Saqui’s style was what set her apart. It was described as “fantastic rather than graceful, abrupt and fearless, striking by its originality rather than charming by its elegance.” She wore flamboyant costumes and tall headdresses that captured the eye and interest. Rather than adopting the slow and ballet-like movements of other tightrope artists of the time, Saqui chose to display her athleticism with quick, energetic routines, often with an element of surprise. She acted out famous battles on a horizontal rope, or charged up a nearly vertical one into a blaze of fireworks, or dropped from the sky, as if from nowhere.

There was one moment in her sparkling career where Saqui fell from favor. She was so beloved of Napoleon that she became overconfident and daringly placed an eagle—his symbol—on her carriage. She rode in this carriage triumphantly around France, performing for troops between battles in the Peninsular war, until the eagle was noticed by an official. Napoleon ordered her to remove it, and Saqui, humiliated by his rejection, went into a sort of self-exile. But then the Emperor was defeated only a few years later, and she was forced to find a new patron anyway.

To all appearances, this hiccup didn’t harm her much. Her career in England rivaled her success in France, and she was never out of work or low on praise until she retired from public performances in 1845. Even then, a theater she had opened with her husband continued to bring her fame until Messr. Saqui died, and his brother wasted all the profits on fantastic and ridiculous schemes that all failed.

Poor Madame Saqui grew bitter and pompous in her old age, reliving every golden moment to spite everyone around her. She was, to use a worn-out phrase, a fallen star, born to shine brightly and to dim into obscurity. But her legacy lived on in many subsequent fearless and enterprising funambulists (yes, that’s a real word, and it means “fun to walk”—just kidding, it means tightrope walker).

December 30, 2020

Auld Lang Syne

Most of us have heard at least the first few bars of the song “Auld Lang Syne,” but not many of us really know where it came from. It is a song from an ancient Scottish celebration called Hogamanay, held on New Year’s Eve, and which was spread throughout the English-speaking world by Robert Burns, who wrote down the lyrics in 1788 (they were published after his death, in 1796).

The phrase means “days gone by,” and is interestingly at odds with many other English traditions around the New Year. The song has to do with remembering past experiences and wondering whether they should be forgotten, but most traditions for the New Year involve getting rid of the old and welcoming the new.

For instance, in preparation for New Year’s Eve, houses would be cleaned and swept free of ashes, dust, rags, and any perishables, in a symbolic purge of the old. On New Year’s Eve, families would wait until the clock struck 12 midnight, and then the head of the household would open the door to usher out the old year and welcome the new. It was considered bad luck to hold onto the things of the old year.

Which is odd, because only a few days earlier was the most generous season of giving. Christmas Day and Boxing Day (the day after Christmas) were traditionally the days for wealthy landowners to welcome their tenants and neighbors, rich and poor alike, to feasts or parties or balls, or to give presents of meat or other valuable foods to the deserving. One would think they would like to remember such things, and carry that spirit into the New Year.

But perhaps that is what Burns was trying to say, in publishing the words to that old song to the world: good things should not be forgotten. Let’s remember the times we were good, and the times that were good to us, and move forward for old times’ sake.

December 16, 2020

Macadamised is not nuts

First of all, Happy Birthday to Jane Austen! One of my favorite authors of all time, and my favorite Regency author—of course! How much we are indebted to her for the whole Regency romance thing!

In an earlier post, I rhapsodized about sidewalks, and now I’m going to do it again—but about roads.

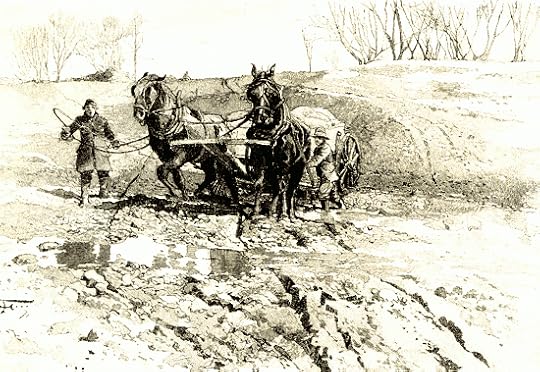

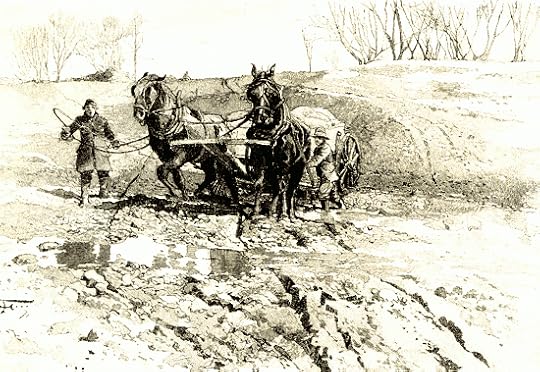

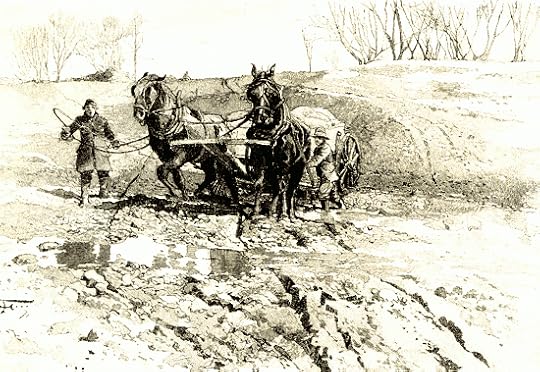

Time was, roads were made up of rocks held together by mud, and you can see by the above picture how effective that construction was against wet weather. The mud would thicken and heave up the rock, or turn into a quagmire, or it would run off altogether, leaving bare chunks of stone that were next to impossible to get your vehicle—let alone the horses—over.

Enter John Louden McAdam, a Scottish engineer who made his fortune in a counting house before turning his attention to the state of the roads. He began in Scotland with the Ayreshire Turnpike Trust, where he learned just how ineffective the prevailing road construction and repair methods were. Then he moved to Bristol, England, where he was appointed as General Surveyor to the Bristol Corporation in 1804.

After experimenting on roads around Bristol and Bath, with positive results, he presented treatises to Parliament beginning in 1816, convincing government to approve drastic changes to road construction practices, including in materials used, and initiated a huge reconstruction project that would revolutionize the roadways of the British Isles, and then beyond.

What is a Macadamised road? Well, it is carefully constructed with layers of of rock and gravel, with a slight curvature, so that rainwater would run off quickly and not soak into the road and ruin the foundation. The rock layer was made up of stones no larger than 7.5 cm (3 in), which was covered by a 5 cm (2 in) layer of gravel no larger than 2 cm (.75 in) each. This top layer was not pressed down during construction—rather, the regular traffic of the road compressed it into a tight, solid mass that was weatherproof enough to last for decades.

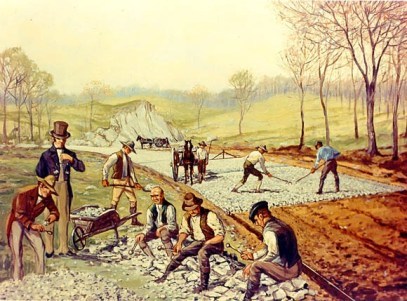

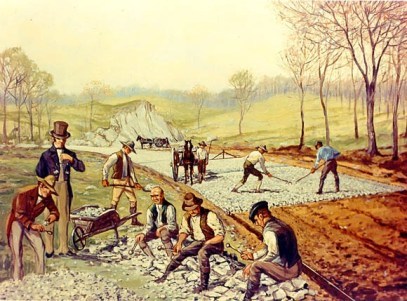

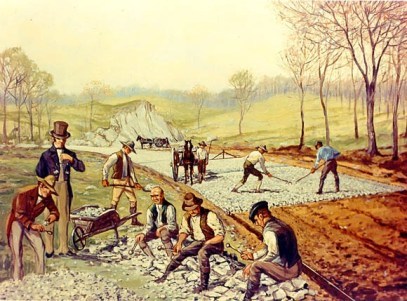

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826John McAdam’s process was so much simpler and less labor intensive than previous methods that it quickly caught on and spread through the British Isles, and then to the US and beyond. His process was improved upon by later engineers, who added different types of binders, including tar—hence the birth of the word “tarmac.”

So the next time your city does a major road reconstruction, think of people like the poor driver of the vehicle pictured above, and thank John McAdam that you live after his time.

Macadamised has nothing to do with nuts

First of all, Happy Birthday to Jane Austen! One of my favorite authors of all time, and my favorite Regency author—of course! How much we are indebted to her for the whole Regency romance thing!

In an earlier post, I rhapsodized about sidewalks, and now I’m going to do it again—but about roads.

Time was, roads were made up of rocks held together by mud, and you can see by the above picture how effective that construction was against wet weather. The mud would thicken and heave up the rock, or turn into a quagmire, or it would run off altogether, leaving bare chunks of stone that were next to impossible to get your vehicle—let alone the horses—over.

Enter John Louden McAdam, a Scottish engineer who made his fortune in a counting house before turning his attention to the state of the roads. He began in Scotland with the Ayreshire Turnpike Trust, where he learned just how ineffective the prevailing road construction and repair methods were. Then he moved to Bristol, England, where he was appointed as General Surveyor to the Bristol Corporation in 1804.

After experimenting on roads around Bristol and Bath, with positive results, he presented treatises to Parliament beginning in 1816, convincing government to approve drastic changes to road construction practices, including in materials used, and initiated a huge reconstruction project that would revolutionize the roadways of the British Isles, and then beyond.

What is a Macadamised road? Well, it is carefully constructed with layers of of rock and gravel, with a slight curvature, so that rainwater would run off quickly and not soak into the road and ruin the foundation. The rock layer was made up of stones no larger than 7.5 cm (3 in), which was covered by a 5 cm (2 in) layer of gravel no larger than 2 cm (.75 in) each. This top layer was not pressed down during construction—rather, the regular traffic of the road compressed it into a tight, solid mass that was weatherproof enough to last for decades.

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826John McAdam’s process was so much simpler and less labor intensive than previous methods that it quickly caught on and spread through the British Isles, and then to the US and beyond. His process was improved upon by later engineers, who added different types of binders, including tar—hence the birth of the word “tarmac.”

So the next time your city does a major road reconstruction, think of people like the poor driver of the vehicle pictured above, and thank John McAdam that you live after his time.

McAdamised is not nutty

First of all, Happy Birthday to Jane Austen! One of my favorite authors of all time, and my favorite Regency author—of course! How much we are indebted to her for the whole Regency romance thing!

In an earlier post, I rhapsodized about sidewalks, and now I’m going to do it again—but about roads.

Time was, roads were made up of rocks held together by mud, and you can see by the above picture how effective that construction was against wet weather. The mud would thicken and heave up the rock, or turn into a quagmire, or it would run off altogether, leaving bare chunks of stone that were next to impossible to get your vehicle—let alone the horses—over.

Enter John Louden McAdam, a Scottish engineer who made his fortune in a counting house before turning his attention to the state of the roads. He began in Scotland with the Ayreshire Turnpike Trust, where he learned just how ineffective the prevailing road construction and repair methods were. Then he moved to Bristol, England, where he was appointed as General Surveyor to the Bristol Corporation in 1804.

After experimenting on roads around Bristol and Bath, with positive results, he presented treatises to Parliament beginning in 1816, convincing government to approve drastic changes to road construction practices, including in materials used, and initiated a huge reconstruction project that would revolutionize the roadways of the British Isles, and then beyond.

What is a Macadamised road? Well, it is carefully constructed with layers of of rock and gravel, with a slight curvature, so that rainwater would run off quickly and not soak into the road and ruin the foundation. The rock layer was made up of stones no larger than 7.5 cm (3 in), which was covered by a 5 cm (2 in) layer of gravel no larger than 2 cm (.75 in) each. This top layer was not pressed down during construction—rather, the regular traffic of the road compressed it into a tight, solid mass that was weatherproof enough to last for decades.

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826

The building of the first macadamised road in the US, 1826John McAdam’s process was so much simpler and less labor intensive than previous methods that it quickly caught on and spread through the British Isles, and then to the US and beyond. His process was improved upon by later engineers, who added different types of binders, including tar—hence the birth of the word “tarmac.”

So the next time your city does a major road reconstruction, think of people like the poor driver of the vehicle pictured above, and thank John McAdam that you live after his time.