Corey Robin's Blog, page 96

September 29, 2013

The History of Fear, Part 3

Today, in my third post on the intellectual history of fear, I talk about Tocqueville’s theory of democratic anxiety. (For Part 1, Hobbes on fear, go here; for Part 2, Montesquieu on terror, go here.)

I suspect readers will be more familiar with Tocqueville’s argument. But that familiarity is part of the problem. Tocqueville’s portrait of the anxious conformist, the private self amid the lonely crowd, has come to seem so obvious that we can no longer see how innovative, how strange and novel, it actually was. And how much it departed from the world of assumption that, for all their differences, bound Hobbes to Montesquieu.

For more on all that, buy the book. But in the meantime…

• • • • •

There are many who pretend that cannon are aimed at them when in reality they are the target of opera glasses.

—Bertolt Brecht

Just fifty years separate Montesquieu’s death in 1755 from Tocqueville’s birth in 1805, but in that intervening half-century, armed revolutionaries marched the transatlantic world into modernity. New World colonials fired the first shot of national liberation at the British Empire, depriving it of its main beachhead in North America. Militants in France lit the torch of equality, and Napoleon carried it throughout the rest of Europe. Black Jacobins in the Caribbean led the first successful slave revolution in the Americas and declared Haiti an independent state. The Age of Democratic Revolution, as it would come to be known, saw borders transformed, colonies liberated, nations created. Warfare took on an ideological fervor not seen in over a century, with men and women staking their lives on the radical promise of the Enlightenment.

Alexis de Tocqueville

But more than any particular advance, it was a new sense of time and space that distinguished this revolutionary world from its predecessor. Montesquieu came of age in the twilight of Louis XIV’s sixty-three-year reign. The uninterrupted length of Louis’ rule left a deep impression on The Spirit of the Laws—of time standing still, of politics moving at a glacial pace. The Age of Democratic Revolution set a new tempo for political life. Jacobins in France announced a new calendar, proclaiming 1792 the Year One. They tossed out laws bearing the traces of time immemorial. They took new names, affected new manners, and voiced new ideas. History books still register this extraordinary compression of time, with dynasties rising and falling within months and years rather than decades or centuries. Even Kant, with his obsessive punctuality, reportedly could not keep up with the pace of events: on the morning in 1789 when he heard of the fall of the Bastille, he stepped out the door for his daily walk later than usual.

Politics not only accelerated; it thickened, as amateurs rushed on stage, demanding recognition as political actors in their own right. Prior to the Age of Democratic Revolution, political life was a graceful but delicate dance between king and court. But suddenly the lower classes were given the opportunity to make, rather than watch, history. According to Thomas Paine, politics would no longer be “the property of any particular man or family, but of the whole community.” With plebeian recruits jostling for space, “the soil of common life,” Wordsworth noted, grew “too hot to tread upon.”

As late as France’s Revolution of 1848, even the most liberal of aristocrats would feel squeezed by this inrush of new bodies. On the morning of February 24, just after the Parisian insurrections had begun, street demonstrators confronted Alexis de Tocqueville, soon to be minister of foreign affairs, on his stroll to the Chamber of Deputies.

They surrounded me and greedily pressed me for news; I told them that we had obtained all we wanted, that the ministry was changed, that all the abuses complained of were to be reformed, and that the only danger we now ran was lest people should go too far, and that it was for them to prevent it. I soon saw that this view did not appeal to them.

“That’s all very well, sir,” said they, “the Government has got itself into this scrape through its own fault, let it get out of it as best it can.”

“. . . If Paris is delivered into anarchy,” I said, “and all the Kingdom is in confusion, do you think that none but the King will suffer?”

Whether Tocqueville’s “we” was a reference to his interlocutors in the street or colleagues in the Chamber of Deputies, it suggested the populist familiarity that high politics had now acquired, a political immediacy simply unthinkable under the Old Regime.

Honoré Daumier, The Uprising

These changed dimensions of time and space would utterly transform how Tocqueville—indeed, how his entire generation, and generations after them—thought about political fear. It would do so in two ways: first, in his sense that it was the mass, and not the individual, that drove events; second, in his recasting of Hobbes’s fear and Montesquieu’s terror as mass anxiety.

Tocqueville believed that the crashing entrance of so many untrained political actors made it impossible for anyone to undertake, on his own, significant political action. “We live in a time,” he noted, “and in a democratic society where individuals, even the greatest, are very little of anything.” Or, as Michelet, describing the plight of the individual amid the mass, put it: “Poor and alone, surrounded by immense objects, enormous collective forces which drag him along.” For all their differences, Hobbes’s sovereign and Montesquieu’s despot were singular figures of epic proportion, projecting their shadow across an entire landscape. The mass eclipsed such figures, allowing no one, not even a despot, to put his stamp on the world. There simply wasn’t enough room.

For Tocqueville, the mass meant more than political congestion: it threatened to dissolve the very boundaries of the self. Not by crushing the self, as Montesquieu had envisioned, but by merging self and society. Unlike the frontispiece of Leviathan, where the individuals composing the sovereign’s silhouette insisted upon their own form, the canvas of revolutionary democracy depicted a gathered hulk, with no recognizable human feature or discrete part. So complete was each person’s assimilation to the mass, it simply did not make sense to speak anymore of individuals. “By dint of not following their own nature,” John Stuart Mill gloomily concluded, men and women no longer had a “nature to follow.”

The new political tempo of the Age of Democratic Revolution, Tocqueville claimed, also produced a new kind of fear. With everything in the world changing so fast, no one could get his bearings. This confusion and loss of control made for free-floating anxiety, with no specific object. Montesquieu’s victims were terrified of tangible threats: punishment, torture, prison, death; Hobbes’s subjects feared specific dangers: the state of nature and the coercive state. The anxiety of Tocqueville’s citizens, by contrast, was not focused upon any concrete harm. Theirs was a vague foreboding about the pace of change and the liquefying of common referents. Uncertain about the contours of their world, they sought to fuse themselves with the mass, for only in unity could they find some sense of connection. Or they submitted to an all-powerful, repressive state, which restored to them a sense of authority and permanence. Anxiety, then, was aroused not by intimidating power—as fear had been for Hobbes and terror had been for Montesquieu—but by the existential condition of modern men and women. Anxiety was not a response to state repression; it induced it.

The Lonely Crowd

With mass anxiety giving rise to political repression, with the experience of those below forcing the actions of those above, Tocqueville completely transformed fear’s political meaning and function, signaling a permanent departure from the worlds of Hobbes and Montesquieu. Redefined as anxiety, fear was no longer thought of as a tool of power; instead, it was a permanent psychic state of the mass. And when the government acted repressively in response to this anxiety, the purpose was not to inhibit potential acts of opposition by keeping people down (Hobbes) or apart (Montesquieu), but to press people together, giving them a feeling of constancy and structure, relieving them, at least temporarily, of their raging anxiety. Thus did Tocqueville take yet one more step away from the political analysis of fear offered by Hobbes, and set the stage for Hannah Arendt, who would complete the journey.

…

But Tocqueville also departed from assumptions about fear that both Hobbes and Montequieu, despite their considerable differences, had shared. Unlike Hobbes or Montesquieu, Tocqueville saw the lines of anxiety’s genesis, cultivation, and transmission extending upward, from the deepest recesses of the mass psyche to the state. Hobbes and Montesquieu believed that the state needed to take certain actions to arouse fear or terror, that the initiative came from above. Tocqueville turned that assumption upside down, claiming that anxiety was the automatic condition of lonely men and women, who either forced or facilitated the state’s repressive actions. To the degree that the state acted repressively, it was merely responding to the demands of the mass. Because the mass was leaderless, divested of guiding elites and discrete authorities, state repression was a genuinely popular, democratic affair.

Unlike Montesquieu or Hobbes, Tocqueville suggested that the individual members of the mass who sought to lose themselves in the state’s repressive authority were culturally and psychologically prone to submission. Hobbes and Montesquieu believed that the individual who was to be afraid or terrified had to be created through the instruments of politics—elites, ideology, and institutions in Hobbes’s case, violence in Montesquieu’s. But in Tocqueville’s eyes, politics did not have to do anything at all. The anxious self was already on hand. No matter how politics and power were configured, the self would be anxious by virtue of his psychology and culture.

Ultimately, it was this vision of the democratic individual amid the lonely crowd that made Tocqueville’s vision of mass anxiety so terrifying. In claiming that anxiety did not have to be crafted, that it was a constitutive feature of the democratic self and its culture, Tocqueville suggested that danger came from within, that the enemy was a psychological fifth column lurking in the heart of every man and woman. As he wrote in a notebook, “This time the barbarians will not come from the frozen North; they will rise in the bosom of our countryside and in the midst of our cities.”

Hobbes had tried to focus people’s fear on a state of nature that lay in the future and in the past and on a real sovereign in the present, Montesquieu on a despotic terror that lay in the future or in the far-off lands of Asia. Both sought to focus people’s fear on objects outside themselves or their countries. Tocqueville turned people’s attention inward, toward the quotidian betrayals of liberty inside their anxious psyches. If there was an object to be feared, it was the self’s penchant for submission. From now on, individuals would have to be on guard against themselves, vigilantly policing the boundaries separating them from the mass. At the height of the Cold War, American intellectuals would revive this line of thought, arguing that the greatest danger to Americans was their own anxious self, ever ready to hand over its freedom to a tyrant. Warning against the “anxieties which drive people in free society to become traitors to freedom,” Arthur Schlesinger concluded that there was, in the United States, a “Stalin in every breast.”

The other object to be feared was the egalitarian culture from which the democratic self arose. Tocqueville did not call for a reversal of democratic gains or a retreat from equality. He was far too much a realist and believer in the revolution’s gains to join the chorus of royalist reaction. Instead, he argued that to preserve the gains of the revolution, to help the democratic individual fulfill his promise as a genuine agent, the self would have to be shored up by creating firm structures of authority, restoring to it a sense of local affiliation, fostering religion and other sources of meaning, situating the self in civic associations whose function was less political than psychological and integrative. To counter mass anxiety, egalitarians and liberals, democrats and republicans, should cease their assault on society’s few remaining hierarchies. They should not participate in the socialist movement to centralize and enhance the power of a redistributive state. Instead, they should actively cultivate localism, institutions, and elite authority; these remnants of the Old Regime were the only bulwark against an anxiety threatening to introduce the worst forms of tyranny seen yet. The task, in other words, was not to continue the assault on the Old Regime but to stop it, to focus attention not on overturning the remains of privilege—local institutions and elites, religion, social hierarchies—but on enhancing them: these were the only social facts standing between democracy and despotism, freedom and anxiety.

One hundred and fifty years later, communitarian intellectuals in North American and Western Europe would offer a similar argument.

September 28, 2013

The History of Fear, Part 2

Yesterday, I inaugurated my series of posts on the intellectual history of fear with a discussion of Hobbes’s theory of rational fear. Today, I continue with a discussion of Montesquieu’s account of despotic terror. (Each of these discussions is an excerpt from my book Fear: The History of a Political Idea.)

Montesquieu is not often read by students of political theory. He’s become a bit of a boutique-y item in the canon, the exclusive preserve of a small group of scholars and pundits who tend to treat him as a genteel guardian of an anodyne tradition of political moderation. With their endless paeans to the rule of law and the separation of powers, these interpreters miss what’s most interesting and disruptive in Montesquieu. I’ve tried to recapture some of that here.

But again, if you want to read more, buy the book.

• • • • •

Fear always remains. A man may destroy everything within himself, love and hate and belief, and even doubt, but as long as he clings to life, he cannot destroy fear.

Hobbes wrote about fear in the midst of political collapse, when the centripetal forces of civil war could no longer be contained by established norms of religion or history. So unnerving was this experience of political entropy that he sought to have it permanently imprinted on the European mind, there being “nothing more instructive towards loyalty and justice than . . . the memory, while it lasts, of that war.” Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu—a French aristocrat born in 1689, a full decade after Hobbes’s death—took up the question of fear just as that memory began to fade. Montesquieu’s was a world suffering not from the confusion of disorder but from the clarity of established rule. By the time of Montesquieu’s birth, Louis XIV had turned a country that only narrowly escaped the revolution that wrecked Britain into the most orderly state in Europe.

Convinced that “a little harshness was the greatest kindness I could do my subjects,” Louis concentrated political power in his own hands, subduing nobles and commoners alike. He seized control of France’s armies, turning semiprivate militias into soldiers of the crown. He banished the aristocracy from royal councils of power, relying instead on three trusted advisors and an efficient corps of officials in the countryside. He snatched veto power from local grandees accustomed to striking down royal edicts in regional parlements. He bankrupted the nobility through obscure methods of taxation; others he corrupted with frivolous titles, assigning them to positions of responsibility over his kitchen and stables. A class that had shared power with the royal family for generations was reduced to competing for such privileges as helping the king get dressed in the morning and perching on a footstool near the queen. Louis, the French historian Ernest Lavisse aptly noted, ruled with “the pride of a Pharaoh” and possessed, according to a character in Montesquieu’s The Persian Letters, “a high degree of talent for making himself obeyed.”

Louis XIV

Montesquieu had a visceral awareness of this aristocratic displacement. As a participant in the Bordeaux parlement and a substantial landowner involved in the wine trade, he chafed at royal interference in local matters, especially restrictions on the production and sale of wine. Everything about the reign of Louis XIV—the eclipse of the nobility, the drive toward centralized power, the loss of local institutions—he identified with despotism, and any limitation on royal power earned his support as the mark of reform. Combining a rearguard defense of noble privilege with a visionary critique of centralized power, he took positions sometimes traditional, sometimes reformist, but always opposed to the absolutism favored by Hobbes.

This was the world and the politics that prompted Montesquieu to launch his reconsideration of Hobbesian fear, a revision so profound and complete it would shape intellectual perception for centuries to come. Political fear was no longer to be thought of as a passion bearing an elective affinity to reason; from now on, political fear was to be understood as despotic terror. Unlike Hobbesian fear, despotic terror was devoid of rationality and unsusceptible to education. It was an involuntary, almost physiological response to unmitigated violence. The terrorized possessed none of the inner life that Hobbes attributed to the fearful. They were incapable of thought and moral reflection; they could not deliberate or even flee. They cowered and crouched, hoping only to fend off the blows of their tormentor.

Montesquieu also reconceived the politics of fear. Where Hobbesian fear was a tool of political order, serving ruler and ruled alike, Montesquieu believed that terror satisfied only the depraved needs of a savage despot. Brutal and sadistic, the despot cared little for the polity. He had no political agenda; he sought only to quench his thirst for blood. The Hobbesian sovereign was aided by influential elites and learned men, scattered throughout civil society, who saw it in their interest to collaborate with him. The despot decimated elites and obliterated institutions, subduing any social organization not entirely his. While the Hobbesian sovereign generated fear through the rule of law and moral obligation, the despot dispensed with both.

Why this shift from fear to terror? Part of it was due to context. Creating political order in the wake of Louis XIV simply did not pose the same challenge to the Frenchman that it had to the Englishman. When Montesquieu tried to imagine a state of nature, as he did in the opening pages of The Spirit of the Laws, he could barely muster eight short paragraphs on the topic. The sheer brevity of his account—not to mention its benign descriptions—suggests how unfazed the political imagination of his day was by the specter of civil war.

But part of this shift was due to a change in political sensibility. Unlike Hobbes, who yearned for absolute government, Montesquieu sought to limit government power. Where Hobbes believed sovereigns should guard all political power as their own, Montesquieu argued for a government of “mediating” institutions. In his ideal polity, individuals and groups, housed in separate institutions, would share and compete for power. Forced to negotiate and compromise with each other, they would produce political moderation, the touchstone of personal freedom. Montesquieu argued for social pluralism and toleration—also checks, he believed, on the one-size-fits-all regime Louis XIV seemed bent on creating. With his vision of limited government, tolerance, political moderation, and personal freedom, Montesquieu was to become one of liberalism’s chief spokespersons, about as similar to Hobbes as a butterfly is to a wasp.

Montesquieu

And yet beneath their considerable differences lay a deep vein of agreement. Like Hobbes, Montesquieu turned to fear as a foundation for politics. Montesquieu was never explicit about this; Hobbesian candor was not his style. But in the same way that the fear of the state of nature was supposed to authorize Leviathan, the fear of despotism was meant to authorize Montesquieu’s liberal state. Just as Hobbes depicted fear in the state of nature as a crippling emotion, Montesquieu depicted despotic terror as an all-consuming passion, reducing the individual to the raw apprehension of physical destruction. In both cases, the fear of a more radical, more debilitating form of fear was meant to inspire the individual to submit to a more civilized, protective state.

Why would a liberal opposed to the Hobbesian vision of absolute power resort to such a Hobbesian style of argument? Because Montesquieu, like Hobbes, lacked a positive conception of human ends, true for all people, to ground his political vision. Montesquieu’s liberalism was not the egalitarian liberalism of the century to come, nor was it the conscience-stricken protoliberalism of the century it had left behind. Unlike Locke, whose argument for toleration was powered by a vision of religious truth, and unlike later figures such as Rousseau or Mill, whose arguments for freedom were driven by secular visions of human flourishing, Montesquieu pursued no beckoning light. He wrote in that limbo period separating two ages of revolution, when weariness with dogma and wariness of absolutism made positive commitments difficult to come by and even more difficult to sustain. His was a skeptical liberalism: ironic, worldly, elegant—and desperately in need of justification.

Despotic terror supplied that justification, lending his vision of limited government moral immediacy, pumping blood into what might otherwise have seemed a bloodless politics. Montesquieu did not know—and did not care to enquire—whether we were free and equal, but he did know that terror was awful and had to be resisted. Thus was liberalism born in opposition to terror—and at the same time yoked to its menacing shadow.

But hitching liberalism to terror came at a price: It obscured the realities of political fear. Montesquieu painted an almost cartoonish picture of terror, complete with a brutish despot straight out of central casting, and brutalized subjects, so crazed by terror they couldn’t think of or for themselves. So did he overlook the possibility that the very contrivances he recommended as antidotes to terror—toleration, mediating institutions, and social pluralism—could be mobilized on its behalf. An expression of the despot’s deranged psyche, Montesquieu’s terror was an entirely nonpolitical or antipolitical affair, circumventing political institutions and sidestepping the political concerns of men. The polemical impulse behind his account was clear: If Montesquieu could show that despotic terror destroyed everything men held dear, and if he could show that terror possessed none of the attributes of a liberal polity, terror could serve as the negative foundation of liberal government. The more malignant the regime, the more promising its liberal alternative.

Built into Montesquieu’s argument, then, was a necessary exaggeration of the evil against which it was arrayed. Though repressive, the rule of Louis XIV did not entirely warrant Montesquieu’s overheated depictions, prompting Voltaire to complain that Montesquieu “satirizes more than he judges” and that he “makes us wish that so noble a mind had tried to instruct rather than shock.” Montesquieu was not unaware of the flaws in his account. In a youthful work, The Persian Letters, he offered plentiful evidence to suggest that his mature conception of despotic terror, stated in The Spirit of the Laws, was as much political pornography as it was social vision. In The Persian Letters, Montesquieu described a form of fear quite similar to that depicted by Hobbes. Rational and moral, fear relied upon education; it aided rather than subdued the self; it depended upon a powerful ruler working in concert with elites; it required the collaboration of all sectors of society. But in his later years, Montesquieu could no longer abide this youthful gloss. So he rejected the earlier vision, as have subsequent writers, who would ignore or misinterpret The Persian Letters, resulting in the distorted vision of terror we possess to this day. Montesquieu’s, then, is a cautionary tale, revealing the pitfalls of a liberalism that relies on terror and thereby misconstrues it, making the Frenchman a creature of not only his own time, but also our own.

…

But what exactly was this fear, this despotic terror? Curiously, The Spirit of the Laws never defines it. Part of Montesquieu’s unwillingness to define it was due no doubt to his intellectual temperament. He was repelled by the austere architecture of Hobbesian thought, in which unadorned definitions gave rise to severe edifices of theoretical conclusion, a style of deductive reasoning he believed mirrored the harsh simplicity of despotic rule.

But Montesquieu’s refusal to define terror registered an even deeper conviction. Terror, he had come to believe, was a great nullifying force, so oriented toward destruction and negation it could not sustain anything suggesting presence or concreteness. “Everything around” despotism, he observed, was “empty.” Terror’s most telling sign was silence, the desolation of verbal space signaling both the dissolution of men capable of speech and the disappearance of a world capable of description. No words, no definitions, could withstand terror’s decimating energies.

Hobbesian fear—and the fear Montesquieu described in the harem—traveled in a world of things, among men with ends to pursue and goods to be sought. Absence and loss were certainly fear’s companions: there was, after all, no more categorical loss than death. But the fear of death was a powerful emotion for Hobbes precisely because it conveyed to its sufferer the prospect of losing the goods he valued in life. The fact that the generation of Hobbesian fear required the cooperation of elites and institutions only added to this sense that fear flourished in a world of things. The denser the world, the more opportunities for depriving men of the objects that mattered to them, the greater the possibilities for arousing fear. In an empty space where human affections were thin and the objects of human attachment few, fear would find an inhospitable terrain.

In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu conceived an altogether different relationship between terror, self, and world. Terror preyed upon a person stripped of selfhood—of reason, moral aspiration, the capacity for agency, and a fondness for things in the world. The more self a person possessed, the more capable he was of resisting terror. The more connected he was to the world and its objects, the more resources he would have to challenge the despot. Deprived of self and world, he was the perfect victim of despotic terror. The ideal environment for terror was a society in which social classes and complicating hierarchies had been eviscerated and the individual was forced to stand alone—not unlike the world, Montesquieu believed, of Louis XIV. Liberated from the thick constitution of medieval ranks and orders, the despot would be free to wield his sword with unequivocal force. The most fertile climate for despotic terror, then, was not a dense atmosphere of desiring selves, collaborating elites, and robust institutions, but a vast expanse of nothingness, from which liberalism derived its somethingness.

…

Hobbes thought that a person’s fear of death was an expression of that person’s most intimate desires and wishes. All fearless people were alike— brash, foolish, enthralled by death—but a fearful person was fearful in his own distinctive way. For Montesquieu, it was the reverse. Because the terrified were incapable of reason, agency, and formulating their own ends, they possessed none of the irregularities distinguishing one person from the next. Terror fed on the dull sameness of animals motivated by nothing but the biological imperative of staying alive. The victim’s “portion, like beasts,’” was “instinct, obedience, and chastisement.” The fear of death could not be linked to the goods of a particular life, for it flourished only in the absence of those goods: “In despotic countries one is so unhappy that one fears death more than one cherishes life.” In free societies, obedience was “naturally subject to eccentricities.” Free subjects thought too highly of themselves to slavishly obey; they forced their rulers to accommodate their demands. Not so in despotism. A de-individualizing experience, despotic terror made no room for pluralism, difference, and individuality.

In recent years, intellectuals of varying stripes have taken the liberal tradition to task for its celebration of the independent, autonomous self. A figure of titanic but chilly remoteness, the liberal self is supposed to be Kant’s bleak gift to modern morals. According to Michael Sandel, the liberal a self is “an active, willing agent,” who chooses her beliefs rather than embrace or discover those she has inherited from parents, teachers, and friends. She is not bound by her “interests and ends.” She “possesses” such ends but is not “possessed” by them. She lurks, like a spider, behind all the strands connecting her to the objects of the world—content in her remove, autonomous at the center of her austere web.

Immanuel Kant

The original vision of a self detached from its ends and the world, however, was born not in triumph but in grief. Long before Kant, long before the liberal subject of communitarian complaint, there was Montesquieu’s victim, a fragile being severed from its basic goods and the world’s objects. Dispossessed of contingent aims, ends, and desires, the victim was divested of every unique relationship and circumstance that made him who he was. For only after shaving off these distinctive layers of self could the despot act upon a creature of pure physicality.

Despite these differences between the proverbial liberal self, and Montesquieu’s brittle victim of terror, the two figures did share an elusive affinity. Kant’s self may not have been the victim Montesquieu envisioned, but Kant could only think of the self as he did because Montesquieu had redefined terror to be an entirely physical phenomenon. By stripping terror of the emblems of selfhood and by conceiving those emblems as checks against terror, Montesquieu made it possible for subsequent theorists to think of fear, redefined as terror, as an experience unhinged from the life of the mind. If a person were rational or moral, Montesquieu suggested, he was not likely to be found among the terrorized.

Kant picked up on this contrast between terror, on the one hand, and selfhood, on the other, only he turned it in an entirely different direction. Like the despot, Kant sought to strip the self of its contingent features—its particular ends, its attachment to immediate circumstances, its objects of desire. But where the despot uncovered a creature ripe for terror, Kant discovered an agent of moral freedom, a pure good will, attuned solely to the dictates of reason, who could act upon the requirements of duty without the “admixture of sensuous things.” Such a person, Kant believed, would be incapable of fear, precisely because he had been liberated from the things of this world, including his physical self. But where Montesquieu’s stripped-down self was prepared for a descent into hell, Kant’s rose gloriously to the kingdom of ends. Thus was the liberal self conceived in the shadow of terror.

…

While Sigmund Freud is associated with the twentieth century’s assault on the sunny rationalism that Montesquieu and the Enlightenment supposedly inaugurated, we see here how closely Freud’s worldview paralleled Montesquieu’s, how much Montesquieu anticipated the sensibilities of our own time. (“There is hardly an event of any importance in our recent history,” Hannah Arendt would later write, “that would not fit into the scheme of Montesquieu’s apprehensions.”) Writing after World War I, Freud claimed that the fundamental conflict within men and women was between the instincts of life and death. The life instinct propelled the self out into the world for the sake of sexual and emotional congress, political and social union. The death instinct sought to return the self to a condition of utter stillness and separation, before birth, where the tensions and conflicts associated with life had ceased. What made the death instinct so powerful was the dim memory of the inorganic state that preceded all life. “It must be an old state of things,” Freud wrote, “an initial state from which the living entity has at one time or other departed and to which it is striving to return,” an idea that explained why “the goal of all life is death.” That memory of a prior inorganic state lay behind the human drive toward self-destruction, as evidenced by the World War I: it was why men and women not only traveled toward death, but also sought to advance the pace of the journey.

Sigmund Freud

Montesquieu’s despotic terror was like the death instinct, an adjutant of decomposition, restoring self and society to a primal stillness. Liberal politics, by contrast, was like the life instinct: It sought to put things together, to build up rather than break down. It worked against the coercive impulse to ease oneself back into a lifeless past, and for that reason, was difficult and counterintuitive. Taking something apart is always easier than putting it together, for disassembly returns things to their simplest forms. A liberal polity demanded that its leaders “combine powers, regulate them, temper them, make them act.” It required “a masterpiece of legislation that chance rarely produces.” Despotism, by contrast, “leaps to view.” Where moderate polities required “enlightened” leaders and officials “infinitely more skillful and experienced in public affairs than they are in the despotic state,” despotism settled for the “most brutal passions.”

Hobbes is often considered a more pessimistic theorist of politics than Montesquieu, but it was the Frenchman who truly possessed the more terrifying vision. No matter how absolutist or repressive his Leviathan, Hobbes believed in the indissoluble presence of men and women, of discrete agents whose participation was necessary for the creation of any political world, no matter how frightening. They were confused, vain, and obnoxious, but their recklessness spoke to a more capacious truth—that dissolution was not the way of the world. Montesquieu spoke on behalf of a darker dispensation. For all the evil the despot was supposed to unleash, he was in the end a mere catalyst, setting in motion forces of nature that were far beyond his control and that would ultimately engulf him as well. If there was any genuine actor in Montesquieu’s story of this descent into hell, it was not human beings but the impersonal drive toward nothingness, which forced its way through the most civilized facades and corresponded to the elemental processes of life itself.

Montesquieu’s politics thus bore a peculiar relationship to terror. On the one hand, terror had to be fought, consuming, if necessary, Europe’s entire fund of political energy. On the other hand, terror seemed more real, more in sync with the deep movements of nature, than liberal ideals of moderation and freedom.

But if ought entails can, how could liberalism take up a struggle against such an indefatigable foe? The solution was, first, to localize terror, and, second, to externalize it. Even though terror threatened all polities, particularly monarchies, Montesquieu thought it could be enclosed within one type of regime, despotism, and that a liberal or moderate regime could keep it at bay. For someone who believed that terror was the universal tendency of all political movement, this was an ironic conclusion, overturning centuries of teaching about how fear ought to be managed. Fear had previously been as a problem for all moral beings. Its challenges were universal, its boundaries ethical. Even Montaigne, usually invoked as Montesquieu’s predecessor, believed that though fear was a great “fit,” it could be overcome by recalling one’s “sense of duty and honor.” Montesquieu envisioned the domain of fear along radically different lines. He suggested that terror was a passion with a specific locale, that it could be contained by the concrete borders of a moderate regime. Thus, when Hegel later ended his discussion of African despotism by writing, “We shall therefore leave Africa at this point, and it need not be mentioned again,” he was invoking more than a literary turn of phrase. He was voicing Europe’s new conviction that fear tracked the lines of territorial rather than moral geography.

Hegel’s comment pointed to a second element of Montesquieu’s strategy: his externalization of terror. Though Montesquieu believed much of Europe was heading toward despotism, he depicted terror as lying primarily outside of Europe, particularly in Asia. Montesquieu may not have invented the concept of Oriental despotism, but he gave it a new lease on life, portraying an entire region and people languishing in primitivism and barbarism. Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, one of Montesquieu’s early critics, decried his use of dehumanizing stereotypes, claiming that Montesquieu had so distorted the East, he inadvertently offered a justification for colonialism from the West. A theory designed to denounce despotic terror at home unintentionally provided an excuse for practicing it abroad.

But there was more than crypto-colonialism going on here, for Montesquieu seemed to believe that by situating terror abroad, Europe could escape its effects at home. This may not have been the first time that a writer turned upon the rest of the world for relief from his own, projecting crude stereotypes he secretly feared were true of his native land; it certainly would not be the last.

September 27, 2013

The History of Fear, Part 1

Long before I was writing or thinking about the right, I was writing and thinking about politics and fear. That project began as a dissertation in the early 1990s and concluded with my first book Fear: The History of a Political Idea, which was published in 2004. When I embarked upon the project, few in the American academy were interested in fear; by the time I finished it, everyone, it seemed, was. What had happened in the intervening years, of course, was 9/11.

Fear is divided into two parts: the first is an intellectual history of fear, examining how theorists from Thomas Hobbes through Judith Shklar have thought about the problem; the second offers my own analysis of fear, drawing on everything from McCarthyism to Stalinism, from the Dirty Wars to the American workplace.

Because the second part of the book—especially its analysis of the workplace—has gotten more attention in the last few years, I wanted to highlight the first part here. In particular, I wanted to give readers a sense of how various our ideas about political fear have been, how innovative (and sometimes misleading) our modern conceptions of fear are, and how interesting Hobbes, Montesquieu, Tocqueville, and Arendt (the main protagonists of my history) can be.

So with this post, I’m going to inaugurate a series on this blog, in which I post excerpts from each of my five chapters on the intellectual history of fear. Part 1, today’s post, will look at Hobbes’s account of rational fear; Part 2 will look at Montesquieu’s account of despotic terror; Part 3, at Tocqueville’s account of democratic anxiety; Part 4, at Arendt’s account of total terror; and Part 5, at the theories of fear we’ve seen since the end of Cold War, which I divide into two categories: the liberalism of anxiety (communitarianism) and the liberalism of terror (what is often called political liberalism).

I hope you find some of this of interest. And that you buy the book.

• • • • •

“No matter how important weapons may be, it is not in them, gentlemen the judges, that great power resides. No! Not the ability of the masses to kill others, but their great readiness themselves to die, this secures in the last instance the victory of the popular uprising.”

It was on April 5, 1588, the eve of the Spanish Armada’s invasion of Britain, that Thomas Hobbes was born. Rumors of war had been circulating throughout the English countryside for months. Learned theologians pored over the book of Revelation, convinced that Spain was the Antichrist and the end of days near. So widespread was the fear of the coming onslaught it may well have sent Hobbes’s mother into premature labor. “My mother was filled with such fear,” Hobbes would write, “that she bore twins, me and together with me fear.” It was a joke Hobbes and his admirers were fond of repeating: Fear and the author of Leviathan and Behemoth—Job-like titles meant to invoke, if not arouse, the terrors of political life—were born twins together.

Thomas Hobbes

It wasn’t exactly true. Though fear may have precipitated Hobbes’s birth, the emotion had long been a subject of enquiry. Everyone from Thucydides to Machiavelli had written about it, and Hobbes’s analysis was not quite as original as he claimed. But neither did he wholly exaggerate. Despite his debts to classical thinkers and to contemporaries like the Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius, Hobbes did give fear special pride of place. While Thucydides and Machiavelli had identified fear as a political motivation, only Hobbes was willing to claim that “the original of great and lasting societies consisted not in mutual good will men had toward each other, but in the mutual fear they had of each other.”

But more than Hobbes’s insistence on fear’s centrality makes his account so pertinent for us, for Hobbes was attuned to a problem we associate with our postmodern age, but which is as old as modernity itself: How can a polity or society survive when its members disagree, often quite radically, about basic moral principles? When they disagree not only about the meaning of good and evil, but also about the ground upon which to make such distinctions? Establishing communion among subscribers to the same political faith is difficult enough; a community of believers, after all, still argues about the meaning of its sacred texts. But what happens when that community no longer reads the same texts, when its members begin from such disparate starting points, pray to such different gods, that they cannot even carry on an argument, much less conclude it?

Hobbes called this condition the “state of nature,” a situation of radical conflict about the meaning of words and morals, producing corrosive distrust and open violence. “In the state of nature,” Hobbes wrote, “every man is his own judge, and differeth from other concerning the names and appellations of things, and from those differences arise quarrels, and breach of peace.” This state of nature was not an extraordinary moment, no sudden storm over an otherwise placid sea. It was endemic to the human condition, constantly threatening a state of war. In fact, wrote Hobbes, it was a state of war.

Hobbes warmed to the fear of death—not just the affective emotion, but the cognitive apprehension of bodily destruction—because he thought it offered a way out of this state of nature. Whatever people deem to be good, Hobbes argued, they should recognize that self-preservation is the precondition for their pursuit of it. They should realize that peace is the prerequisite of their preservation, and that peace is best guaranteed by their agreeing to submit absolutely—that is, by ceding a great deal of the rights that are by nature theirs—to the state, which he called Leviathan. That state would have complete authority to define the rules of political order, and total power to enforce those rules.

Accepting this principle of self-preservation did not require men to give up their underlying faith, at least not in theory: it only asked them to acknowledge that their pursuit of that faith necessitated their being alive. When we act out of fear, Hobbes suggested, when we submit to government for fear of our own lives, we do not forsake our beliefs. We keep faith with them, ensuring that we remain alive so that we can pursue them. Fear does not betray the individual; it is his completion. It is not the antithesis of civilization but its fulfillment. This is Hobbes’s counterintuitive claim about fear, cutting against the grain of later argument, but nevertheless finding an echo in the actual experience of men and women submitting to political power.

We shall consider here three other elements of Hobbes’s treatment of fear, for they also speak to our political condition. First, Hobbes argued that fear had to be created. Fear was not a primitive passion, waiting to be tapped by a weapons-wielding sovereign. It was a rational, moral emotion, taught by influential men in churches and universities. Though the fear of death could be a powerful motivator, men often resisted it for the sake of honor and glory. To counter this tendency, the doctrine of self-preservation and the fear of death had to be propounded by preachers and teachers, and by laws instructing men in the ground of their civic duty. Fear had to be thought of as the touchstone of a people’s commonality, the essence of their associated life. It had to address their needs and desires, and be perceived as defending the most precious achievements of civilization. Otherwise, it would never create the genuine civitas Hobbes believed it was meant to create.

Second, though Hobbes understood fear to be a reaction to real danger in the world, he also appreciated its theatrical qualities. Political fear depended upon illusion, where danger was magnified, even exaggerated, by the state. Because the dangers of life were many and various, because the subjects of the state did not naturally fear those dangers the state deemed worth fearing, the state had to choose people’s objects of fear. It had to persuade people, through a necessary but subtle distortion, to fear certain objects over others. This gave the state considerable leeway to define, however it saw fit, the objects of fear that would dominate public concern.

Finally, Hobbes marshaled his arguments about fear not only to overcome the impasse of moral conflict, but also to defeat the revolutionary legions contending at the time against the British monarchy. The English Revolution broke out in 1643 between royalist forces allied with Charles I and Puritan armies marching on behalf of Parliament. It concluded in 1660 with the restoration of Charles’s son to the throne. Between those years, Britain witnessed the war-related death of some 180,000 men and women, the beheading of Charles I, and the decade-long rule of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritans.

Scholars have long debated whether this bloody struggle was a modern revolution or the last in a long line of religious conflicts unleashed by the Reformation. To be sure, Cromwell’s forces did not seek a great leap forward: they hoped to return England to God’s rule, conceiving themselves as restorative rather than progressive agents. Nevertheless, there was a revolutionary and democratic dimension to their actions, which Hobbes perceived and believed had to be countered. “By their harangues in the Parliament,” he complained of the revolutionary leaders, “and by their discourses and communication with people in the country,” the revolutionaries made ordinary people “in love with democracy.” Hobbes’s arguments about fear were in no small measure directed at the revolutionary ethos of these Puritan warriors. And this lends his account a decidedly repressive, even counterrevolutionary character, the ramifications of which we shall see in the work of later theorists like Tocqueville and contemporary intellectuals writing today, as well as in the actual practice of political fear.

What Hobbes’s arguments add up to is an acute analysis, never quite seen before or since, of fear’s moral and political dimensions. Though Hobbes owed much to his predecessors, his appreciation of moral pluralism and conflict drove him to a new, and distinctly modern, conception of the relationship between fear and morality. Previous writers like Aristotle and Augustine believed that fear grew out of society’s shared moral ethos, with the objects of a people’s fear reflecting that ethos. Convinced that such an ethos no longer existed, Hobbes argued that it had to be created. Fear would serve as its constituent element, establishing a negative moral foundation upon which men could live together in peace. Thus, where previous writers treated fear as an emanation of a shared morality, Hobbes conceived of it as the catalyst of that morality. And though Hobbes was indebted to his contemporaries’ analysis of self-preservation, he knew that the men of his age—tangled in revolution, indifferent to their own death—were not likely to accept it. This inspired some of his deepest reflections about how the fear of death could be generated and sustained by the sovereign and his allies throughout civil society.

While Hobbes’s analysis of fear owes more to classical and contemporary sources than we might think, his imagined orchestration of fear is more prophecy than reiteration, envisioning how modern elites will wield fear in order to rule, and how modern intellectuals will rely on fear, even as they distance themselves from Hobbes, to create a sense of common purpose.

…

But Hobbes’s doctrine evokes another side of modern politics—not the inaugural moment of counterinsurgent fear, when the forces of activist reform are defeated, but the succeeding era of quiet complacence and sober regard for family, business, locality, and self. After the demobilization of any popular movement, men and women tend to their own affairs, worrying about the everyday business of survival and success, forgoing larger visions of collective transformation. In her account of Pinochet’s Chile, for example, journalist Tina Rosenberg writes of Jaime Pérez, a socialist student leader during Salvador Allende’s last year in power. After the 1973 military coup, which ended 150 years of Chilean democracy, Pérez fled from public life. He did not protest, he “slept.” He traded his old car for a new one—every year—and bought three color TVs. Explaining his silence, Pérez says, “All I knew was that life was good,” and in certain respects, it was.

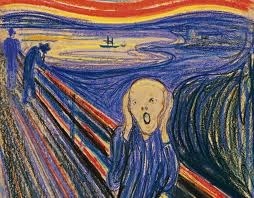

The Scream

The United States has also seen such moments—most famously in the wake of the McCarthy-era purges. Once the tumult of repressive politics died down, men and women retreated to the goods of family life and getting ahead. Critics lambasted the social types of the 1950s as conformists, coining phrases like “the man in the gray flannel suit,” “the lonely crowd,” and “status anxiety.” But these were terms of moralistic accusation that evaded or sublimated the reality of McCarthyism. People were frightened during the 1950s, and they were frightened because of political repression. Their fear bore none of fear’s obvious marks; they did not resemble the terrorized face in Edvard Münch’s famous portrait The Scream. They looked instead like Hobbesian man—reasonable, purposive, and careful never to take a step in the wrong direction. Fear didn’t destroy Cold War America: it tamed it. It secured for men and women some measure of what they deemed to be their own good. American citizens didn’t betray their former principles: under the weight of intense coercion, their principles changed. Or they opted to forgo certain principles—political solidarity—for the sake of others—familial obligation, careerism, personal security. However they justified their decisions, their choices reveal the influence of Hobbesian fear. And if it sounds strange to contemporary ears to call it fear, that is only a testament to Hobbes’s success.

In this regard, I can think of no more representative figure linking Hobbes’s vision to the twentieth century than Galileo. According to his most celebrated biographer, Hobbes “extremely venerated and magnified” Galileo, whose influence is evident throughout Hobbes’s work. In the 1930s, Bertolt Brecht revived the story of Galileo as a twentieth-century parable of revolutionary courage and counterrevolutionary fear. Brecht turned Galileo into the improbable hero of a new proletarian science, a revolutionary slayer of medieval dragons. By threatening the church’s authority, Brecht suggested, Galileo’s teachings promised a world where “no altar boy will serve the mass/No servant girl will make the bed.” But when “shown the instruments” of torture by the Inquisition, Galileo recanted his revolutionary scientific theories.

Charles Laughton as Galileo

At the end of Brecht’s play, Galileo confesses to shame and remorse over his capitulation. “Even the Church will teach you that to be weak is not human,” he spits out. “It is just evil.” Though he managed after his recantation to pursue a clandestine science, the very solitariness of the pursuit—its separation from a larger project of collective, radical transformation—betrayed the scientific enterprise, which demands publicity, solidarity, and above all, courage. “Even a man who sells wool, however good he is at buying wool cheap and selling it dear, must be concerned with the standing of the wool trade. The practice of science would seem to call for valor.” Most damning of all, Galileo realizes that he never was in as much danger from the Inquisition as he believed. Like the subjects of Leviathan, whose fear turns a mere spitfrog into a terrifying giant, Galileo magnified his own weakness and the strength of his opponents. “At that particular time, had one man put up a fight, it could have had wide repercussions. I have come to believe that I was never in real danger; for some years I was as strong as the authorities,” he says. “I sold out,” he wanly concludes.

Whether Galileo is a coward or a realist (and in good Brechtian fashion, the playwright suggests there might not be much difference between the two), one thing is clear: Galileo’s fear of death is connected to the goods he valued in life. As much as he speaks on behalf of a larger political vision of science, so does he subscribe to a more domestic conception of himself and his ends. Brecht’s Galileo is a bon vivant, a lover of the finer things—good food, good wine, leisure. His science, he believes, depends upon his stomach. “I don’t think well unless I eat well. Can I help it if I get my best ideas over a good meal and a bottle of wine?” He adds, “I have no patience with a man who doesn’t use his brains to fill his belly.” He hopes to use the proceeds from his science to secure a good dowry for his daughter, to buy books, to acquire the necessary free time to pursue pure research. Thus, when he chooses to abide by the dictates of the Inquisition and pursue his research on the sly, he acts in accordance with a principle that has been his all along: science depends first and foremost on personal comfort.

In choosing silence over solidarity, comfort over comradeship, Galileo swaps one truth for another. It is not that fear silences his true self, that self-interest gets the better of his moral code. It is that the only way he can imagine fulfilling his ends is to capitulate to fear. That is how fear works in a repressive state. The state changes the calculus of individual action, making fear seem the better instrument of selfhood. The emblematic gesture of the fearful is thus not flight but exchange, its metaphorical backdrop not the rack but the market. “Blessed be our bargaining, whitewashing, death-fearing community,” Galileo howls. And in the distance, one can see Hobbes nodding in silent agreement, without the slightest hint of irony.

September 25, 2013

Classical Liberalism ≠ Libertarianism

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations:

Whenever the legislature attempts to regulate the differences between masters and their workmen, its counsellors are always the masters. When the regulation, therefore, is in favour of the workmen, it is always just and equitable; but it is sometimes otherwise when in favour of the masters. Thus the law which obliges the masters in several different trades to pay their workmen in money and not in goods, is quite just and equitable.

Adam Smith, Lectures on Jurisprudence:

The rich and opulent merchant who does nothing but give a few directions, lives in far greater state and luxury and ease and plenty of all the conveniencies and delicacies of life than his clerks, who do all the business. They too, excepting their confinement, are in a state of ease and plenty far superior to that of the artizan by whose labour these commodities were furnished. The labour of this man too is pretty tollerable; he works under cover protected from the inclemency in the weather, and has his livelyhood in no uncomfortable way if we compare him with the poor labourer. He has all the inconveniencies of the soil and the season to struggle with, is continually exposed to the inclemency of the weather and the most severe labour at the same time. Thus he who as it were supports the whole frame of society and furnishes the means of the convenience and ease of all the rest is himself possessed of a very small share and is buried in obscurity. He bears on his shoulders the whole of mankind, and unable to sustain the load is buried by the weight of it and thrust down into the lowest parts of the earth, from whence he supports all the rest. (emphasis added)

September 24, 2013

Van Jones Does Gershom Scholem One Better

Do you think that you’ve shown enough love toward President Obama?…Where is the love for this president?…You’ve got the first black president, and where is the love? I understand the critique, but where is the love?”

It’s like what Gershom Scholem wrote to Hannah Arendt in response to Eichmann in Jerusalem:

There is something in the Jewish language that is completely indefinable, yet fully concrete — what the Jews call ahavath Israel, or love for the Jewish people. With you, my dear Hannah, as with so many intellectuals coming from the German left, there is no trace of it.

Only classier.

The Voice of the Counterrevolution

Count of Artois to Calonne, August 8, 1790:

We must serve the king and the queen in spite of themselves.

This is the authentic voice, the most perfect expression, of the counterrevolution: We are the saviors of the old regime, we will save the old regime from itself, we will—shades of Rousseau—force it to be free.

If things seem better in Jerusalem, it’s because they’re worse

My friend Adina Hoffman, whose biography of the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali is a small treasure, has a wonderful piece in The Nation this week on the visit by the Iranian film director Mohsen Makhmalbaf to Jerusalem this past summer. Though film buffs will read and love the entire piece, it also has a lengthy interlude on Jerusalem that should be of special interest to readers of this blog. (Adina lived in Jerusalem throughout the 90s and the aughts, and now divides her time between Jerusalem and New Haven.) The piece is behind the paywall at The Nation, which is a shame, but the editors have liberated it for a day (today). Anyway, here’s a taste:

These are strange days in Jerusalem. On the eve of the month of Ramadan and at the height of summer vacation—as, nearby, Egypt seethes and Syria smolders—the city is both more bustling and more bewildering than ever, and Makhmalbaf’s unlikely appearance only underscores the confusing nature of this Middle Eastern cultural moment.

In the upscale Jewish neighborhoods on the western side of town, things are looking surprisingly swank. Petunias have been planted en masse in the municipal parks. A hundred new street cleaners have been enlisted by city hall to sweep up after the hordes crowding the pedestrian malls. The Ottoman-era train station—derelict for decades—has been tastefully refurbished and has just opened its doors as an elegant entertainment compound featuring chic restaurants, an airy gallery, and a pretty, landscaped foot and bike path that runs, High Line–style, along the old tracks. Mahaneh Yehudah, the outdoor market, is booming. Alongside the well-established vegetable and spice stands, funky bars and trendy cafés have popped up; the place is teeming with locals and tourists, old ladies dragging shopping carts and young hipsters taking drags from their hand-rolled cigarettes.

Palestinians, too, mingle easily in this mix, in large part because of the municipal light rail, which has been running for two years now. For almost a decade, the construction of the rail line and its protracted delays threatened to destroy already depressed downtown West Jerusalem by rendering it a dusty, nearly impassible building site. Now, winding like some great electric eel down Jaffa Road, the rail line cuts a sleek, silvery figure that, in the gritty context of Jerusalem, appears almost fantastical. The gentle tolling of the train’s bell adds to that enchanted feel—as does the utterly mixed population riding the train itself.

Twelve years ago, at the height of the second intifada, when suicide bombers were blowing themselves up with scary regularity in the middle of downtown and the very presence of a Palestinian on an Israeli bus was enough to make most of the Jewish riders squirm, it would have been next to impossible to imagine the scene on the light rail this summer: ultra-Orthodox women in wigs and Muslim women with their hijabs, miniskirted Jewish teenagers and young Palestinian men in jeans not only sitting and standing calmly side by side, but often packed together without panic as the train glides its way from stop to stop. They rarely exchange a word, but there they are, shoulder to shoulder, in the air-conditioned slither toward de facto “unification” of the city. Each station is announced in Hebrew, Arabic and English, which in any other town might seem an ordinary nod to the linguistic needs of the various people using the train. But in traumatized, sectarian Jerusalem, the co-existence of these languages, as of the riders themselves, is startling for its sheer normalcy.

If things seem better in the old-new city of Jerusalem, it’s in part because they’re worse. Israel technically annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 war, but it has taken some four and a half decades to create the infrastructural facts on the ground that make the occupation such a concrete and humdrum state of affairs. The light rail is just one example, erasing as it does the border between the Jewish and Arab sides of town. In the last ten years or so, the notorious wall or “separation barrier” has, in addition, cut East Jerusalem off from the West Bank, rendering this once-thriving urban hub of Palestinian life little more than a demoralized and demoralizing backwater. This is no doubt one of the main reasons why so many Palestinians have decided this summer to go west to eat ice cream and shop in pop-music-blasting Jewish shoe stores. It’s a chance to pass through the looking glass that this city often is and spend just a few day-tripping hours on the cleaner, more prosperous side of town.

Systematically neglected by the municipality and battered by the larger political and economic situation, East Jerusalem is home to 39 percent of the city’s total population, though its people receive only a small fraction of the city’s resources. West Jerusalem has forty-two post offices, East Jerusalem, nine; the West boasts seventy-seven municipal preschools, the East has ten; eighteen welfare offices function in West Jerusalem, while the whole of the East counts three. Since 1967, a third of Palestinian land in East Jerusalem has been expropriated. According to Israel’s National Insurance Institute, the poverty rate among the city’s Palestinians is 79.5 percent. Of East Jerusalem’s children, 85 percent live below the poverty line. (The percentage of poor Jewish Jerusalemites is 29.5 percent.) The numbers are at once shameful, slightly numbing and somehow too banal to register with most of the world at large, though this is the way a viable Palestinian Jerusalem ends: not with a bang but a bureaucratic whimper.

Not one to be swayed by such sad statistics, Israel’s public security minister must have felt it his duty to protect the people of Israel from the existential threat posed by a children’s puppet festival that was scheduled to open at the Palestinian national theater in East Jerusalem on June 22. Claiming without proof that the festival was being sponsored by the Palestinian Authority, in violation of the Oslo Accords, the minister banned it and ordered the theater shuttered for eight days and its director summoned for questioning by the Shin Bet. Protests by Palestinian and international organizations did no good, and a solidarity campaign by various Israeli puppeteers—including no less than Elmo from the local version of Sesame Street—proved useless. The theater remained closed, and the impoverished kids of East Jerusalem were left to entertain themselves in the heat.

Back in West Jerusalem, hawkish high-tech entrepreneur Mayor Nir Barkat decided that what the people of his city really needed this summer was a $4.5 million Formula One race car exhibition. Blocking off traffic on the city’s main thoroughfares for several days, the mayor, a self-declared “motor sports fan and racer,” arranged for a flashy parade of Ferraris, Audis and Grand Prix motorcycles to vroom past the old city walls in the rather mind-bogglingly named Peace Road Show. It is, declared the mayor in his American-sounding English, “great branding, great marketing,” and “great for promoting peace and co-existence.”

And about that peace and co-existence: Barkat also found time this summer to bestow honorary Jerusalem citizenship on billionaire casino tycoon and ideological sugar daddy Sheldon Adelson and his Israeli-born wife. Adelson took the occasion of the Jerusalem ceremony held in his honor to dismiss the Palestinians as “southern Syrians” and to claim that Yasir Arafat “came along with a pitcher of Kool-Aid and gave it to everybody to drink and sold them the idea of Palestinians.” At this festive gathering, complete with the reading of a fancy parchment scroll and the crooning of “That’s Amore” by singers wearing Paul Revere–style tricorne hats, Barkat declared the Adelsons “Zionist heroes of the city.” At the same time, native-born Palestinians from the neighborhood of Silwan are not considered citizens at all, honorary or otherwise. They are, instead, “permanent residents,” many of them threatened with eviction by the municipality, which is working closely with Jewish settler groups and various government agencies to demolish their homes and put in their place a pseudo-biblical park and tourist attraction called the King’s Garden. The city has also recently approved plans to construct apartments for Jewish settlers in the heart of another Palestinian neighborhood, Sheikh Jarrah, where families are literally being thrown out into the street. That’s amore.

The mayor is a busy man. In late May, he squeezed in a trip to Los Angeles, where he attended a reception hosted in his honor by the evangelical birther Pat Boone, who long ago did his bit for Israel by writing and singing the lyrics to the theme for the movie Exodus. (“This land is mine, God gave this land to me /This brave, this golden land to me.”) While in LA, Barkat met with Hollywood producers, to whom he offered special tax breaks and subsidies to shoot their movies in the Holy City, where a special department has already been established to handle film permits and logistical matters. It’s “not only good business. It’s good Zionism,” he enthused to The Hollywood Reporter. “It’s the right thing to do.”

Which brings us back to Mohsen Makhmalbaf….

…

“The first thing that shocked me” about Israel, says Makhmalbaf, now dressed in a white shirt and looking slightly subdued the morning after the first Jerusalem screening of The Gardener, is that “it was like Iran. I felt I was in Iran.”…

After today, you can read the article in pdf form at Adina’s website (it’s the piece called “Salaam Cinema”; click on the link at Adina’s site). And while you’re there, check out some of Adina’s other essays, on everything from S.Y. Agnon and Elias Khoury to archives and archaeology in Jerusalem. Or buy the book she wrote with her husband, the poet and translator Peter Cole, on the Cairo Geniza. Enjoy!

September 22, 2013

I was on NPR Weekend Edition

I was on NPR’s Weekend Edition this morning, talking to Rachel Martin about WAS’s. The WAS, you may recall from a post I did in the spring, is a Wrongly Attributed Statement. I wound up writing more about WAS’s at the Chronicle Review earlier this week, and that’s how NPR came to me. Here’s the opening of my Chronicle piece:

Sometime last semester I was complaining to my wife, Laura, about a squabble in my department. I can’t remember the specifics—that’s how small and silly the argument was—but it was eating at me. And eating at me that it was eating at me (tiffs are as much a part of academe as footnotes and should be handled with comparable fuss). After listening to me and voicing the requisite empathy, Laura said, “Any idiot can survive a crisis; it’s the day-to-day living that wears you out.” I looked at her, puzzled. “Chekhov,” she said. Puzzled gave way to impressed. “Chekhov,” I said, with a tip of the head. Impressed gave way to skeptical. “Chekhov?”

So we did what any couple does on the verge of an argument: We Googled it. And sure enough, there it was: lots and lots of hits, many of them attributing this bit of wisdom to Chekhov. But where had he said it? Not a single hit—at least not that we could find—identified a play, short story, letter, diary entry, note, or testimonial in which Chekhov or any of his characters says this.

I decided to do some more sleuthing. And then I stopped myself. I’d been here before, I realized. I was in the realm of the WAS.

And have a listen over at NPR.

September 21, 2013

David Petraeus: Voldemort Comes to CUNY

Monday, September 9, was David Petraeus’s first class at CUNY. As he left Macaulay Honors College, where he’s teaching, he was hounded by protesters. It wasn’t pretty; the protesters were angry and they didn’t hold back.

The protesters’ actions attracted national and international media attention—and condemnation. Not just from the usual suspects at Fox but from voices at CUNY as well.

Macaulay Dean Ann Kirschner issued a formal statement on the Macaulay website and then took to her blog in order to further express her dismay:

Before and during Dr. Petraeus’ class, however, a group of protesters demonstrated in front of the college. That demonstration ended before the conclusion of the class. Sometime later, while walking off campus, Dr. Petraeus was confronted by a group of protesters, who surrounded him and persisted in following him, chanting as a group, shouting at him, and pounding on a car that he entered.

Harassment and abusive behavior toward a faculty member are antithetical to the university’s mission of free and open dialogue. Although this may be obvious, this kind of behavior strikes more deeply at the heart of our cherished American right to express our beliefs without threats or fear of retribution.

CUNY Interim Chancellor Bill Kelly issued the following statement:

During the first two weeks of the semester, demonstrators — from within and outside the University– have gathered near the Macaulay Honors College to protest the presence of Visiting Professor David Petraeus. By nature, universities nurture the reasoned expression of dissent, including the right of peaceful protest. CUNY has long embraced the responsibility to encourage debate and dialogue. Foreclosing the right of a faculty member to teach and the opportunity of students to learn is antithetical to that tradition, corrosive of the values at the heart of the academic enterprise. We defend free speech and we reject the disruption of the free exchange of ideas. Accordingly, CUNY will continue to ensure that Dr. Petraeus is able to teach without harassment or obstruction. In so doing, we join with the University Faculty Senate in defending the right of CUNY faculty members to teach without interference.

Even the University Faculty Senate weighed in, sending all CUNY professors the following statement:

Protestors, reportedly including CUNY students, have harassed new Macaulay Honors College Visiting Professor (and former CIA head and general) David Petraeus on his way to class, using epithets, shouting “You will leave CUNY,” and chanting “ Every class David,” expressing an intent to continue their verbal attacks. Because they disagree with Professor Petraeus’ views, these demonstrators intend to deprive him of his ability to teach and the ability of his students to learn from him.

CUNY has long-established policies to protect the academic freedom of faculty, which are essential for the University’s operation as a center of learning.

The Executive Committee of the University Faculty Senate deplores all attacks on the academic freedom of faculty, regardless of their viewpoint. In the past, we have been strong advocates for the freedom of Kristofer J. Petersen-Overton to teach at Brooklyn College without harassment or retaliation.

Professor Petraeus and all members of CUNY’s instructional staff have the right to teach without interference.

Members of the university community must have the opportunity to express alternate views, but in a manner that does not violate academic freedom.

(In an excellent response to the Faculty Senate statement, Petersen-Overton set the record straight about what the Senate did and did not do during his travails.)

That was two weeks ago.

This past Tuesday afternoon, students held another protest against Petraeus, this time outside a Macaulay fundraiser. About 75 people participated, and eyewitnesses say that the cops quickly got rough. According to one report:

“Protestors were marching in a circle on the sidewalk and chanting, but the police forced them into the street and then charged. One of the most brutal things I saw was that five police officers slammed a Queens College student face down to the pavement across the street from Macaulay, put their knees on his back and he was then repeatedly kneed in the back,” said Hunter student Michael Brian. “The student was one of those pointed out by ‘white shirt’ officers, then seized and brutalized. A Latina student was heaved through the air and slammed to the ground.”

This post from Gawker, with video, confirms much of these claims.

Six students were arrested, held in jail for 20 hours, and have now been charged with disorderly conduct, riot, resisting arrest, and obstructing government administration.

And where are Kirschner, Kelly, and the Faculty Senate? Nowhere. What have they said about this police brutality and its relationship to academic freedom? Nothing.

Indeed, Kelly posted his statement in defense of Petraeus yesterday, September 20, four days after the students were beaten up and arrested by the cops. And all throughout the day yesterday, as the intrepid Steve Horn reports, Macaulay’s Twitter feed was filled with bubbly affirmations of free speech and the free exchange of ideas—which are most threatened, apparently, by the strident language of student protesters rather than the brutality of the NYPD.

So that’s where we stand. The delicate flowers of academic freedom at CUNY wilt before the jeers and jibes of a few students but warm to the blazing sun of the state. A four-star general who led two brutal counterinsurgency campaigns in Eurasia, a former head of the CIA whose hazing rituals at West Point alone probably outstrip anything the NYPD did to these students, requires the fulsome support of chancellors, senates, and deans. But six students of color beaten by cops, locked up in prison for a day, and now facing a full array of charges from the state, deserve nothing but the cold silence of their university. So much tender solicitude for a man so wealthy and powerful that he can afford to teach two courses at CUNY for a dollar; so little for these students, whose education is the university’s true and only charge.

It’s a depressing scene, reminiscent of that moment in The Theory of the Moral Sentiments where Smith compares the grief people feel over the discomfort of the powerful to their indifference to the misery of the powerless.

Every calamity that befals [the powerful], every injury that is done them, excites in the breast of the spectator ten times more compassion and resentment than he would have felt, had the same things happened to other men…To disturb, or to put an end to such perfect enjoyment, seems to be the most atrocious of all injuries. The traitor who conspires against the life of his monarch, is thought a greater monster than any other murderer. All the innocent blood that was shed in the civil wars, provoked less indignation than the death of Charles I. A stranger to human nature, who saw the indifference of men about the misery of their inferiors, and the regret and indignation which they feel for the misfortunes and sufferings of those above them, would be apt to imagine, that pain must be more agonizing, and the convulsions of death more terrible to persons of higher rank, than to those of meaner stations.

This morning, my five-year-old daughter floated the proposition that “David Petraeus is Voldemort.” She may be onto something. In the same way that dark wizard turned around so many heads at Hogwarts, so has Petraeus turned our sensibilities upside down at CUNY.

A group of CUNY grad students and faculty have organized a petition against the police brutality; email cunysolidarity@gmail.com to add your signature. And there’s going to be a rally in support of students’ right to protest on Monday, September 23, at 2:30 pm, at Macaulay Honors College, 35 W. 67th Street (between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue).

September 19, 2013

Faculty to University of Oregon: Oh No We Don’t!