Corey Robin's Blog, page 92

December 10, 2013

Socialism: Converting Hysterical Misery into Ordinary Unhappiness for a Hundred Years

In yesterday’s New York Times, Robert Pear reports on a little known fact about Obamacare: the insurance packages available on the federal exchange have very high deductibles. Enticed by the low premiums, people find out that they’re screwed on the deductibles, and the co-pays, the out-of-network charges, and all the different words and ways the insurance companies have come up with to hide the fact that you’re paying through the nose.

For policies offered in the federal exchange, as in many states, the annual deductible often tops $5,000 for an individual and $10,000 for a couple.

Insurers devised the new policies on the assumption that consumers would pick a plan based mainly on price, as reflected in the premium. But insurance plans with lower premiums generally have higher deductibles.

In El Paso, Tex., for example, for a husband and wife both age 35, one of the cheapest plans on the federal exchange, offered by Blue Cross and Blue Shield, has a premium less than $300 a month, but the annual deductible is more than $12,000. For a 45-year-old couple seeking insurance on the federal exchange in Saginaw, Mich., a policy with a premium of $515 a month has a deductible of $10,000.

In Santa Cruz, Calif., where the exchange is run by the state, Robert Aaron, a self-employed 56-year-old engineer, said he was looking for a low-cost plan. The best one he could find had a premium of $488 a month. But the annual deductible was $5,000, and that, he said, “sounds really high.”

By contrast, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the average deductible in employer-sponsored health plans is $1,135.

It’s true that if you’re a family of three, making up to $48,825 (or, if you’re an individual, making up to $28,725), you’ll be eligible for the subsidies. Those can be quite substantive at the lower ends of the income ladder. But as you start nearing those upper limits (which really aren’t that high; below the median family income, in fact), the subsidies start dwindling. Leaving individuals and families with quite a bill, as even this post, which is generally bullish on Obamacare, acknowledges.

Aside from the numbers, what I’m always struck by in these discussions is just how complicated Obamacare is. Even if we accept all the premises of its defenders, the number of steps, details, caveats, and qualifications that are required to defend it, is in itself a massive political problem. As we’re now seeing.

More important than the politics, that byzantine complexity is a symptom of what the ordinary citizen has to confront when she tries to get health insurance for herself or her family. As anyone who has even good insurance knows, navigating that world of numbers and forms and phone calls can be a daunting proposition. It requires inordinate time, doggedness, savvy, intelligence, and manipulative charm (lest you find yourself on the wrong end of a disgruntled telephone operator). Obamacare fits right in with that world and multiplies it.

I’m not interested in arguing here over what was possible with health care reform and what wasn’t; we’ve had that debate a thousand times. But I thought it might be useful to re-up part of this post I did, when I first started blogging, on how much time and energy our capitalist world requires us to waste, and what a left approach to the economy might have to say about all that. It is this world of everyday experience—what it’s like to try and get basic goods for yourself and/or your family—that I wish the left (both liberals and leftists) was more in touch with.

The post is in keeping with an idea I’ve had about socialism and the welfare state for several years now. Cribbing from Freud, and drawing from my own anti-utopian utopianism, I think the point of socialism is to convert hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness. God, that would be so great.

• • • • • •

There is a deeper, more substantive, case to be made for a left approach to the economy. In the neoliberal utopia, all of us are forced to spend an inordinate amount of time keeping track of each and every facet of our economic lives. That, in fact, is the openly declared goal: once we are made more cognizant of our money, where it comes from and where it goes, neoliberals believe we’ll be more responsible in spending and investing it. Of course, rich people have accountants, lawyers, personal assistants, and others to do this for them, so the argument doesn’t apply to them, but that’s another story for another day.

The dream is that we’d all have our gazillion individual accounts—one for retirement, one for sickness, one for unemployment, one for the kids, and so on, each connected to our employment, so that we understand that everything good in life depends upon our boss (and not the government)—and every day we’d check in to see how they’re doing, what needs attending to, what can be better invested elsewhere. It’s as if, in the neoliberal dream, we’re all retirees in Boca, with nothing better to do than to check in with our broker, except of course that we’re not. Indeed, if Republicans (and some Democrats) had their way, we’d never retire at all.

In real (or at least our preferred) life, we do have other, better things to do. We have books to read, children to raise, friends to meet, loved ones to care for, amusements to enjoy, drinks to drink, walks to take, webs to surf, couches to lie on, games to play, movies to see, protests to make, movements to build, marches to march, and more. Most days, we don’t have time to do any of that. We’re working way too many hours for too little pay, and in the remaining few hours (minutes) we have, after the kids are asleep, the dishes are washed, and the laundry is done, we have to haggle with insurance companies about doctor’s bills, deal with school officials needing forms signed, and more.

What’s so astounding about Romney’s proposal—and the neoliberal worldview more generally—is that it would just add to this immense, and incredibly shitty, hassle of everyday life. One more account to keep track of, one more bell to answer. Why would anyone want to live like that? I sure as hell don’t know, but I think that’s the goal of the neoliberals: not just so that we’re more responsible with our money, but also so that we’re more consumed by it: so that we don’t have time for anything else. Especially anything, like politics, that would upset the social order as it is.

…We saw a version of it during the debate on Obama’s healthcare plan. I distinctly remember, though now I can’t find it, one of those healthcare whiz kids—maybe it was Ezra Klein—tittering on about the nifty economics and cool visuals of Obama’s plan: how you could go to the web, check out the exchange, compare this little interstice of one plan with that little interstice of another, and how great it all was because it was just so fucking complicated.

I thought to myself: you’re either very young or an academic. And since I’m an academic, and could only experience vertigo upon looking at all those blasted graphs and charts, I decided whoever it was, was very young. Only someone in their 20s—whipsmart enough to master an inordinately complicated law without having to make real use of it—could look up at that Everest of words and numbers and say: Yes! There’s freedom!

That’s what the neoliberal view reduces us to: men and women so confronted by the hassle of everyday life that we’re either forced to master it, like the wunderkinder of the blogosphere, or become its slaves. We’re either athletes of the market or the support staff who tend to the race.

That’s not what the left wants. We want to give people the chance to do something else with their lives, something besides merely tending to it, without having to take a 30-year detour on Wall Street to get there. The way to do that is not to immerse people even more in the ways and means of the market, but to give them time and space to get out of it. That’s what a good welfare state, real social democracy, does: rather than being consumed by life, it allows you to make your life. Freely. One less bell to answer, not one more.

December 9, 2013

We Are an Open Hillel (Updated Again)

Hillel is one of the rabbis in the Jewish tradition most associated with the spirit of questioning, argument, and debate. Indeed, so intense and multiple were his disagreements with Shammai that a saying emerged from their disputes: “The one law has become two.”

So it seems entire appropriate for the Jewish students of the Swarthmore College Hillel to have adopted the following resolution, declaring themselves to be an “Open Hillel.” The backdrop to this resolution is the decision two weeks ago of the Harvard Hillel not to allow an anti-Israel speaker on its premises. That decision was in keeping with Hillel International’s policy of refusing to work with or or to host anyone who opposes the State of Israel, including the former speaker of the Israeli Knesset (because he was being brought to the Harvard campus by an anti-Israel student group).

Here is the resolution of the Swarthmore Hillel:

Whereas Hillel International prohibits partnering with, hosting, or housing anyone who (a) denies the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish and democratic state with secure and recognized borders, (b) delegitimizes, demonizes, or applies a double standard to Israel, (c) supports boycott of, divestment from, or sanctions against the State of Israel;

And whereas this policy has resulted in the barring of speakers from organizations such as Breaking the Silence and the Israeli Knesset from speaking at Hillels without censorship, and has resulted in Jewish Voice for Peace not being welcome under the Hillel umbrella;

And whereas this policy runs counter to the values espoused by our namesake, Rabbi Hillel, who was famed for encouraging debate in contrast with Rabbi Shammai;

And whereas Hillel, while purporting to support all Jewish Campus Life, presents a monolithic face pertaining to Zionism that does not accurately reflect the diverse opinions of young American Jews;

And whereas Hillel’s statement that Israel is a core element of Jewish life and a gateway to Jewish identification for students does not allow space for others who perceive it as irrelevant to their Judaism;

And whereas Hillel International’s Israel guidelines privilege only one perspective on Zionism, and make others unwelcome;

And whereas the goals of fostering a diverse community and supporting all Jewish life on campus cannot be met when Hillel International’s guidelines are in place;

Therefore be it resolved that Swarthmore Hillel declares itself to be an Open Hillel; an organization that supports Jewish life in all its forms; an organization that is a religious and cultural group whose purpose is not to advocate for one single political view, but rather to open up space that encourages dialogue within the diverse and pluralistic Jewish student body and the larger community at Swarthmore; an organization that will host and partner with any speaker at the discretion of the board, regardless of Hillel International’s Israel guidelines; and an organization that will always strive to be in keeping with the values of open debate and discourse espoused by Rabbi Hillel.

And here are some excerpts from their press release:

Hillel, billing itself as the “Foundation for Jewish Campus Life,” is seen by many as the face of the American Jewish college population. And due to these policies, it is a face that is often seen to be monolithically Zionist, increasingly uncooperative, and completely uninterested in real pluralistic, open dialogue and discussion.

We do not believe this is the true face of young American Jews.

…Rabbi Hillel valued Jewish debate and difference – it was at the core of his practice. We do the same. For us, that is what the name Hillel symbolizes.

Therefore, we choose to depart from the Israel guidelines of Hillel International. We believe these guidelines, and the actions that have stemmed from them, are antithetical to the Jewish values that the name “Hillel” should invoke. We seek to reclaim this name. We seek to turn Hillel – at Swarthmore, in the Greater Philadelphia region, nationally, and internationally – into a place that has a reputation for constructive discourse and free speech. We refuse to surrender the name of this Rabbi who encouraged dialogue to those who seek to limit it.

To that end, Swarthmore Hillel hereby declares itself to be an Open Hillel. All are welcome to walk through our doors and speak with our name and under our roof, be they Zionist, anti-Zionist, post-Zionist, or non-Zionist. We are an institution that seeks to foster spirited debate, constructive dialogue, and a safe space for all, in keeping with the Jewish tradition. We are an Open Hillel.

Update (December 10, 10:40 pm

The head of Hillel International has responded to Swarthmore Hillel. This from the Haaretz.

Hillel International warned its Swarthmore College chapter that it cannot use the Hillel name if it flouts the international Jewish campus group’s Israel guidelines.

The Hillel student organization delivered the warning on Tuesday in a sharply worded letter following the Swarthmore chapter student board’s decision to repudiate Hillel guidelines prohibiting partnerships with groups deemed hostile toward Israel.

In his letter, Hillel’s president and CEO, Eric Fingerhut, warned Swarthmore Hillel’s student communications coordinator, Joshua Wolfsun, that the chapter’s rejection of the guidelines “is not acceptable.”

“I hope you will inform your colleagues on the Student Board of Swarthmore Hillel that Hillel International expects all campus organizations that use the Hillel name to adhere to these guidelines,” Fingerhut wrote. “No organization that uses the Hillel name may choose to do otherwise.”

…

Swarthmore Hillel had said in a statement: “All are welcome to walk through our doors and speak with our name and under our roof, be they Zionist, anti-Zionist, post-Zionist, or non-Zionist.”

Fingerhut, in his letter, rejected the formulation.

“Let me be very clear – ‘anti-Zionists’ will not be permitted to speak using the Hillel name or under the Hillel roof, under any circumstances,” he wrote.

Update (December 11, 11:30 am)

There is now a petition protesting Hillel International’s policy of banning non-Zionist and anti-Zionist speakers and associations with Hillel. I urge you to sign it.

Also, Inside Higher Ed has a very good piece on the controversy.

We Are an Open Hillel

Hillel is one of the rabbis in the Jewish tradition most associated with the spirit of questioning, argument, and debate. Indeed, so intense and multiple were his disagreements with Shammai that a saying emerged from their disputes: “The one law has become two.”

So it seems entire appropriate for the Jewish students of the Swarthmore College Hillel to have adopted the following resolution, declaring themselves to be an “Open Hillel.” The backdrop to this resolution is the decision two weeks ago of the Harvard Hillel not to allow an anti-Israel speaker on its premises. That decision was in keeping with Hillel International’s policy of refusing to work with or or to host anyone who opposes the State of Israel, including the former speaker of the Israeli Knesset (because he was being brought to the Harvard campus by an anti-Israel student group).

Here is the resolution of the Swarthmore Hillel:

Whereas Hillel International prohibits partnering with, hosting, or housing anyone who (a) denies the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish and democratic state with secure and recognized borders, (b) delegitimizes, demonizes, or applies a double standard to Israel, (c) supports boycott of, divestment from, or sanctions against the State of Israel;

And whereas this policy has resulted in the barring of speakers from organizations such as Breaking the Silence and the Israeli Knesset from speaking at Hillels without censorship, and has resulted in Jewish Voice for Peace not being welcome under the Hillel umbrella;

And whereas this policy runs counter to the values espoused by our namesake, Rabbi Hillel, who was famed for encouraging debate in contrast with Rabbi Shammai;

And whereas Hillel, while purporting to support all Jewish Campus Life, presents a monolithic face pertaining to Zionism that does not accurately reflect the diverse opinions of young American Jews;

And whereas Hillel’s statement that Israel is a core element of Jewish life and a gateway to Jewish identification for students does not allow space for others who perceive it as irrelevant to their Judaism;

And whereas Hillel International’s Israel guidelines privilege only one perspective on Zionism, and make others unwelcome;

And whereas the goals of fostering a diverse community and supporting all Jewish life on campus cannot be met when Hillel International’s guidelines are in place;

Therefore be it resolved that Swarthmore Hillel declares itself to be an Open Hillel; an organization that supports Jewish life in all its forms; an organization that is a religious and cultural group whose purpose is not to advocate for one single political view, but rather to open up space that encourages dialogue within the diverse and pluralistic Jewish student body and the larger community at Swarthmore; an organization that will host and partner with any speaker at the discretion of the board, regardless of Hillel International’s Israel guidelines; and an organization that will always strive to be in keeping with the values of open debate and discourse espoused by Rabbi Hillel.

And here are some excerpts from their press release:

Hillel, billing itself as the “Foundation for Jewish Campus Life,” is seen by many as the face of the American Jewish college population. And due to these policies, it is a face that is often seen to be monolithically Zionist, increasingly uncooperative, and completely uninterested in real pluralistic, open dialogue and discussion.

We do not believe this is the true face of young American Jews.

…Rabbi Hillel valued Jewish debate and difference – it was at the core of his practice. We do the same. For us, that is what the name Hillel symbolizes.

Therefore, we choose to depart from the Israel guidelines of Hillel International. We believe these guidelines, and the actions that have stemmed from them, are antithetical to the Jewish values that the name “Hillel” should invoke. We seek to reclaim this name. We seek to turn Hillel – at Swarthmore, in the Greater Philadelphia region, nationally, and internationally – into a place that has a reputation for constructive discourse and free speech. We refuse to surrender the name of this Rabbi who encouraged dialogue to those who seek to limit it.

To that end, Swarthmore Hillel hereby declares itself to be an Open Hillel. All are welcome to walk through our doors and speak with our name and under our roof, be they Zionist, anti-Zionist, post-Zionist, or non-Zionist. We are an institution that seeks to foster spirited debate, constructive dialogue, and a safe space for all, in keeping with the Jewish tradition. We are an Open Hillel.

December 7, 2013

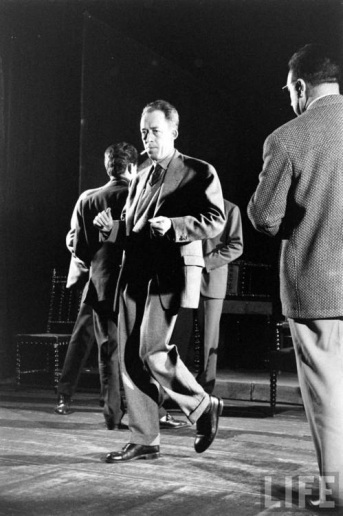

Albert Camus Dancing

December 6, 2013

Jumaane Williams and Dov Hikind

Jumaane Williams is fast on his way to becoming the Gerald Ford of New York City’s progressive Democrats, putting his foot in his mouth on one issue after another. Turns out he has some interesting views on abortion and same-sex marriage.

On abortion, he does the communitarian two-step that was so popular back in the 1990s:

I don’t know that the two choices [pro-life or pro-choice] I have accurately describe what I believe. You have to check off a box of pro-choice and you have to check off a box of pro-life and I don’t know that I’m comfortable in any of those boxes. I am personally not in favor of abortion.

But his big complaint is that men are being left out of the discussion and decision-making process. When a woman aborts her fetus without the knowledge or consent of the man who contributed his sperm, says Williams, “there is no space I think for fathers to express that kind of pain.”

Williams says this happened to him. A woman he was involved with terminated her pregnancy in the first or second month without his knowing it.

“It was just very painful. It’s still painful now,” he said, tearing up as he recalled learning about the abortion. “I have the clear image of the sonogram. I have the clear image of the doctor. I have the clear image of being in the room, hearing the doctor say, ‘Everything’s going along fine.’”

The story sounds a little fishy to me. If the woman he’s talking about had the abortion in the first or second month of her pregnancy, would she have had a sonogram? And as for that “clear image: what could he possibly have seen? This?

Anyway, that’s Williams on abortion.

And here he is on same-sex marriage: “I personally believe the definition of marriage is between a male and a female.” Though he wants the state to get out of the business of marriage altogether.

Between his stance on abortion, same-sex marriage, and the BDS controversy, I’m beginning to think Williams has a lot more in common with Dov Hikind than I realized.

December 4, 2013

When Professors Oppose Unions

Rick Perlstein has a great piece on how faculty respond to grad student unions.

He quotes at length from a letter that a professor of political science at the University of Chicago sent to graduate students in his department who are trying to organize a union there.

What always amuses me about these sorts of statements from faculty is how carefully crafted and personal they are—you can tell a lot of time and thought went into this one—and yet somehow they still manage to attain all the individuality of a Walmart circular. No union contract was ever as standardized or as cookie-cutter as one of these missives. The very homogenization and uniformity that faculty fear a union will foist upon their campus is already present in their own aversion.

Anyway, here’s what the good professor has to say:

First off, let me preface these remarks by saying that when I was in graduate school at Berkeley in the 1990s, I was very active in the graduate student unionization movement. I was shop steward for the political science department for several years and was very active in a three week campus wide teaching strike we held in the fall of 1992. It may also be worth mentioning that I come from a working class family (I was the first and only person in my family to go to college) and I grew up around a lot of issues of collective bargaining. So I’m highly sympathetic to issues of collective action.

The I-come-from-a-working-class-background-my-dad-was-in-a-union-my-aunt-fucked-Walter-Reuther-I-organized-the-workers-at-Flint-this-may-come-as-a-surprise-but-I-actually-am-Cesar-Chavez opening. Check.

That said, I found your co-signed letter to be naive, unconvincing, and, quite frankly, kind of offensive. It is naive in that you seem to really think a union would not change relationships between graduate students and the faculty. I don’t know if either of you have ever been members of a union or worked in a unionized environment, but unions inevitably alter the relationships between union members and the people the interact with, be they management, clients, customers, or what not. The formalization of such relationships is, in fact, the central goal of a union. Your letter says “Our goal is simply to gain a voice in the decisions that affect our working conditions.” Well, these decisions are largely made by the faculty. Thus, if you want a collectivized voice in these decisions, you will be unavoidably shaping your relationships to faculty members.

We make all the decisions around here. Check. (Ask that professor if he even knows how much you make as a TA; they almost never do, though this one seems to. One point for research.)

The union will screw up your very close and personal relationship with your adviser. Check.

Oddly, when you point out that relationships between students and professors at Berkeley, Michigan, and Wisconsin, all of which have unions, are not that different from relationships between students and professors at Chicago, Yale, and Harvard, these peer institutions that these professors would be thrilled to get their students a job at suddenly become tarred with that dreaded word “public” or even worse “state school.”

And when you ask these professors to explain, concretely, why it makes a difference that Berkeley is public and Chicago is private, a thoughtful look will inevitably descend upon them, as they slowly emit the following carefully chosen words: “Well, it’s different at Berkeley. They’re a public university.”

What’s more egregious is the fact that most of the faculty I know do not think of interns [the University of Chicago's term for teaching assistants] as employees but think of the internship as another educational experience.

You’re students, not workers. Check.

Though this one has a novel twist: we, the faculty, think of you as students, not workers.

And just like that, our hard-bitten empiricist turns into the most starry-eyed constructivist.

And now comes the climax.

Every year there are hundreds of applicants for a very small number of slots to study here. You are very lucky to be here, just as I am very lucky to teach here. When you were admitted to the university, you were not hired. You were offered a spot as a student. The university owes you nothing beyond what it initially proposed and what you accepted. To call yourself an employee and complain about an absence of cost-of-living adjustments, health insurance, or the burdens of being a graduate student…sounds both presumptuous and petulant.

You’re privileged, presumptuous, and petulant. Check.

I, on the other hand, am…just another tenured professor at a fancy school. Saying what every other tenured professor at a fancy school has said to any one of his students who managed to tell him that she wanted to form a union too.

Check check check.

Academia: the herd of independent minds.

November 24, 2013

Can I Come Back into the Tent Now, Rabbi Goldberg?

Four days ago, Zbigniew Brzezinski tweeted this:

Obama/Kerry = best policy team since Bush I/Jim Baker. Congress is finally becoming embarrassed by Netanyahu’s efforts to dictate US policy.

— Zbigniew Brzezinski (@zbig) November 19, 2013

Yesterday, Jeffrey Goldberg of The Atlantic tweeted this in response:

Jews run America, suggests ex-national security adviser: https://t.co/1ZH2R7jyuC

— Jeffrey Goldberg (@JeffreyGoldberg) November 24, 2013

Seemed like a crazy read of what Brzezinski said, but it’s the sort of thing I’ve come to expect from Goldberg. I didn’t give it a second thought.

But Logan Bayroff at J Street did. J Street, in case you don’t know, is a liberal-ish Jewish group in the US that’s pushing for a peace settlement with the Palestinians. They call themselves “the political home for pro-Israel, pro-peace Americans.” Not my people, but what are you going to do?

J Street, in case you don’t know, is a liberal-ish Jewish group in the US that’s pushing for a peace settlement with the Palestinians. They call themselves “the political home for pro-Israel, pro-peace Americans.” Not my people, but what are you going to do?

Anyway, Bayroff went after Goldberg:

@JeffreyGoldberg He doesn’t say or even imply that. Willingness to accuse everyone of anti-semitism makes it impossible to respect you

— Logan Bayroff (@Bayroff) November 24, 2013

Goldberg got furious and this morning tweeted this:

I continuously defend @jstreetdotorg‘s place inside the Jewish tent. But the behavior of its employees makes such defenses difficult.

— Jeffrey Goldberg (@JeffreyGoldberg) November 24, 2013

And when he was asked what this rude J Street employee had done to piss him off, Goldberg explained:

@besasley @JeremyBenAmi‘s assistant attacking me for criticizing Brzezinski!

— Jeffrey Goldberg (@JeffreyGoldberg) November 24, 2013

Jeremy Ben-Ami is the head of J Street; Bayroff is his assistant.

Okay, now that we’ve introduced our cast of characters let me say this:

By what authority does Jeffrey Goldberg arrogate to himself the right to defend (with the implicit threat that he might not in the future) someone or some group’s “place in the Jewish tent”? Who elected him Pope to excommunicate or not some heretical Jew? Who made him Defender of the Faith?

(Let’s set aside that the reason he gives for wavering in his commitment to keep J Street in the fold is that one of its impertinent employees had the audacity to criticize him. For reasons that seem perfectly legitimate.)

Isn’t that sort of talk—I’ll defend (or won’t defend) your staying within the tent, but only if you’re well behaved—sort of, well, un-Jewish? I know there are more theologically minded Jews than myself who think they can dictate how one ought to be Jewish, who is or isn’t a Jew, but that’s the point: they ain’t Jeffrey Goldberg. He’s a self-described liberal Zionist, not an Orthodox Jew. But in his cosmos, Zionism is the religion, he’s the rebbe, and the rebbe gets to decide if you’re in or you’re out, if you’re kosher or treif.

Zionists like Goldberg like to style themselves as open, hip, and pluralist. They think what distinguishes them from the Black Hats is their embrace of secular modernity. But as you can see from this incident and the one I discuss below, Zionism has not only made these types intolerant and anti-pluralist; it has turned them into Popes and Inquisitors, enthralled with their imagined power to exile and excommunicate.

Under their watch, one of the most important questions that lies at the heart of the Jewish tradition—What does it mean to be a Jew?—gets taken off the table. Because we already know the answer: support for the State of Israel. If you do, you’re a Jew in good standing; if you don’t, you’re not.

That’s what nationalism—especially nationalism hitched to a state—does to people. It makes the Goldbergs of this world think they can give Jews a passport or take it away. Well, guess what, Rabbi Goldberg: you can’t. I don’t need you defending my right to be in the Jewish tent because that’s not within your, or any other Jew’s, power to decide.

I wish Ben-Ami had jumped in in response to Goldberg and said, “Fuck you, you don’t get to decide who’s a Jew or not.” Instead, he tweeted (never has that word seemed more appropriate) this:

.@JeffreyGoldberg @jstreetdotorg Defense appreciated. Disagreements should be aired with the respect we ask be given to us.

— Jeremy Ben-Ami (@JeremyBenAmi) November 24, 2013

Like I said, not my people. What can you really expect from a group that needs to surround their support for peace in the Middle East with bumper stickers affirming they’re pro-Israel and pro-America?

Anyway, as I said above, this isn’t the first time Goldberg has said something un-Jewish in the name of the Jews. About two years ago he made a similar move, and I wound up writing a lengthy blog about it. Here it is…

• • • • •

As someone who identifies as Jewish—who periodically goes to shul, celebrates some if not all of the holidays, and tries at least some (ahem) of the time to get off the internets for shabbos—yet opposes Zionism, I thought I’d heard all the charges that have been and could be made against me and my tribe. But yesterday, Jeffrey Goldberg, the Atlantic writer and one of the leading voices of liberal Zionism in this country, threw a new one into to the mix.

In my experience, those Jews who consciously set themselves apart from the Jewish majority in the disgust they display for Israel, or for the principles of their faith, are often narcissists, and therefore seem to suffer from an excess of self-regard, rather than self-loathing.

What caught my eye (really, my ear) was not the evident wrongness of the claim, starting with the lazy assumption that those who oppose the State of Israel are somehow setting “themselves apart from the Jewish majority.” It was that “excess of self-regard.” Whether Goldberg knows it or not, or was conscious of it when he used it, that charge has a pedigree in Jewish—or rather anti-Jewish—history.

To be sure, there is within Judaism an injunction, and more generally an ethos, not to separate oneself from the Jewish people. The Wicked Son at the Passover Seder asks, “What does this service [or ritual or story] mean to you?” His wickedness lies in that final hissing “to you”: he refuses to acknowledge that in addition to being an “I” he is also a “We.” Verses in the Pirkei Avot enjoin us not to hold ourselves apart from the community. There’s also a Halachic stipulation that for the sake of practicality and communal living, Jews must abide by legal rulings regarding everyday ritual and civil law. Despite the many differences and disagreements it generates, Judaism is not really a religion of individuals or individualism; it is the religion of a people. Am Yisrael: the people of Israel.

But, as far as I can see, there is little in the tradition that views the dissenter as somehow haughty or superior, narcissistic or self-regarding. And while friends more knowledgeable than I joke that one can always find evidentiary support in the Talmud for some claim or other, this particular one would probably require some digging. If it exists, it’s a subterranean position. And how could it not be? For every two Jews, goes the old saw, there are three opinions. If every unorthodox statement were treated as a symptom of overweening arrogance or pride, well, there’s not enough room in the universe—let alone the Talmud—to contain such a lexicon of self-regard.

In fact, the only document I can think of that even approximates such an accusation is Annie Hall. Think of those scenes where a young Alvie Singer presses his existential concerns (“The universe is expanding”) upon his parents only to be told by his mother, “What is that your business?” and, later, “You never could get along with anyone at school. You were always outta step with the world.” Or perhaps that scene in Hannah and her Sisters where Mickey (the Woody Allen character) tells his parents he’s thinking of converting to Catholicism because he’s afraid there’s no God or life after death, and his father replies, “How do you know?” and his mother, less indulgently, “Of course there’s a God, you idiot! You don’t believe in God?” Aside from these hints that the questioner of—or deserter from—the faith is somehow punching above his weight (and, of course, the characters here are speaking the language of parents rather than Judaism), it’s hard to find this specific rhetoric of accusation that I’m talking about, in which the dissenter is impeached as a presumptuous snob, in the Jewish tradition.

But if you’re not in the mood for digging deep, if you want quick and easy access to that rhetoric, simply put your hand into the garbage can of anti-Semitism. For it is there, in the rubbish of ancient and modern history, that you’ll find the accusation that the Jew who refuses to conform to the ways of the dominant culture—with the culture now understood, of course, to be non-Jewish—is smug and superior, that he assumes he knows better and believes he is better than the majority. Because how else are we to understand a minority insisting upon its own ways over and against the majority?

Robert Wistrich’s A Lethal Obsession: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to the Global Jihad is a veritable compendium of such accusations, from ancient pagans to Vichy officials to Brezhnev’s Soviet Union to the modern Arab world (making full allowances, as Wistrich does not, for the distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism). Over and over, one hears the complaint from the anti-Semite that the Jew has set himself up not only in opposition to, but in judgment upon, the dominant culture. And that in doing so he has presumed himself to be better than that culture.

Of course, that accusation often preys upon the complicated—and by no means uncontroversial—notion of chosenness within the Jewish tradition. Bernard Lazare, the Jewish radical who wrote the first genuine history of anti-Semitism just before the Dreyfus Affair (and whose work had a tremendous influence upon Hannah Arendt), offered a version of this claim. In Wistrich’s lucid paraphrase:

Bernard Lazare was convinced that the “revolutionary spirit of Judaism” had been a major factor in anti-Semitism through the ages. Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Karl Marx were prime examples of Jewish iconoclasts of their time. The Jews, by creating an intensely demanding God of morality and justice whose stern monotheism brooked no toleration of alien deities, threatened the natural order. The prophetic vision of an abstract transcendent Godhead above nature, a deity without form or shape, who had nonetheless created the universe and would in the fullness of time redeem all mankind, was disconcerting, powerful, and mysterious to the pagan world. It was rendered especially irritating by the Jewish claim to be a “chosen people,” a “kingdom of priests,” and a ferment among the Gentiles. Anti-Semitism could best be seen as an instinctive response by the nations of the world to this provocation—to the uncanny challenge of an eternal people, whose refusal to assimilate defied all established historical patterns. Hatred of the Jews was often combined with fear, envy….

Though it seems quite wrong to me to locate the sources of anti-Semitism in anything Jews do or say—and that’s not really Lazare’s point, I don’t think—there can be no doubt, as Wistrich shows, that anti-Semites have consistently chosen to interpret the Jewish insistence on separateness and difference (leave aside the more difficult notion of chosenness) as a bid for superiority.

Conversely, and ironically, for writers like Tom Paine, it is precisely this insistence upon setting themselves apart that has been not only the glory of the Jewish people but the guarantor of whatever is democratic and egalitarian in their culture. In Common Sense, Paine takes up a lengthy disquisition on the question “of monarchy and hereditary succession.” There he makes a special point of noting that the Jews were originally without a king and were governed instead by “a kind of republic administered by a judge and the elders of the tribes.”

But the temptation to monarchy dies hard, Paine observes, even among the Jews. And the reason it dies hard is that the desire to conform, to abandon one’s ways in the face of outside pressure, dies harder. So frequently does Paine recur to the lures and dangers of imitation and conformity—”Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom”; “We cannot but observe that their motives were bad, viz. that they might be like unto other nations, i.e. the Heathens, whereas their true glory laid in being as much unlike them as possible”—that we might say for Paine (at least in Common Sense; Age of Reason sounds a different note) it is the Jew’s refusal to conform that most guarantees his democratic and egalitarian credentials.

For Jeffrey Goldberg, it’s the reverse. It’s the Jew who sets himself apart from the dominant culture—Goldberg’s referring to mainstream Judaism, of course, rather than the culture as a whole, but the structure of the argument is the same—who is making a bid for superiority. And in this respect, Goldberg is aligning himself with neither Judaism nor democracy but their antitheses.

It’s ironic that what started this whole discussion, for Goldberg and excellent journalists like Spencer Ackerman, was the use of the controversial term “Israel-Firster” by critics of Israel and the ensuing debate over whether or not it’s anti-Semitic. I don’t have much of a dog in that fight: I’ve never used and would never use the term, not because it questions the patriotism of American Jews but because it partakes of the vocabulary of patriotism in the first place, a vocabulary I find suspect and noxious from beginning to end. Even so, I’m amazed that someone who is so quick to find anti-Semitism in the words of others is so careless about its presence in his own.

November 23, 2013

Adam Smith ♥ High Wages

The liberal reward of labour, therefore, as it is the effect of increasing wealth, so it is the cause of increasing population. To complain of it, is to lament over the necessary effect and cause of the greatest public prosperity.

…

The liberal reward of labour, as it encourages the propagation, so it increases the industry of the common people. The wages of labour are the encouragement of industry, which, like every other human quality, improves in proportion to the encouragement it receives….Where wages are high, accordingly, we shall always find the workmen more active, diligent, and expeditious, than where they are low.”

November 21, 2013

What a F*ing Scandal the Senate Is

Today, the United States Senate voted to eliminate the filibuster for most presidential nominees. That decision does not apply to legislation or Supreme Court nominees.

Republican John McCain responded to the vote, “Now there are no rules in the United States Senate.” The Reactionary Mind at work. (Incidentally, Patrick Devlin made a similar argument in The Enforcement of Morals, which led H.L.A. Hart to remind him that a change in the rules of an order need not constitute the elimination of that order or of order as such.)

But what does the vote actually mean? As Phil Klinkner explained to me, and as this old Washington Post piece confirms, before this vote, senators representing a mere 11% of the population could block all presidential appointments and all legislation.

From now on, senators representing a mere 17% of the population can block most presidential appointments; senators representing 11% can still block all legislation and all Supreme Court nominees.

The march of democracy.

What a fucking scandal that institution is.

November 16, 2013

Only Bertrand Russell could ever write something like this

I…found that my first draft was almost always better than my second. This discovery has saved me an immense amount of time.

Bastard.

H/t Jim Farmelant.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers