Corey Robin's Blog, page 95

October 8, 2013

Upstairs, Downstairs at the University of Chicago

Back in May at the University of Chicago, this happened (h/t Micah Uetricht):

Two locksmiths with medical conditions were told to repair locks on the fourth floor of the Administration Building during the day. Stephen Clarke, the locksmith who originally responded to the emergency repair, has had two hip replacement surgeries during his 23 years as an employee of the University. According to Clarke, when he asked Kevin Ahn, his immediate supervisor, if he could use the elevator due to his medical condition, Ahn said no. Clarke was unable to perform the work, and Elliot Lounsbury, a second locksmith who has asthma, was called to perform the repairs. Lounsbury also asked Ahn if he could use the elevator to access the fourth floor, was denied, and ended up climbing the stairs to the fourth floor.

The reason Clarke and Lounsbury were told they had to walk up four flights up stairs—with their hip replacements and asthma—is that the University of Chicago has had a policy of forbidding workers from using the elevators in the Administration Building during daytime hours. As the university’s director of labor relations put it: “The University has requested that maintenance and repair workers should normally use the public stairway in the Administration Building rather than the two public elevators.”

Upstairs, downstairs was once a metaphor for how the lower and higher orders of Edwardian Britain lived (servants downstairs, masters upstairs). Nowadays, it’s a literal rendition of the lives of workers at our most elite universities.

After five months of agitation, including the threat of a rally and support from undergraduates and graduate students who are organizing their own union, University of Chicago President Robert Zimmer has at last issued a statement reversing the policy: “Let me state in the simplest of terms what the policy actually is: the elevators are for everybody’s use.”

If this is what it takes workers to be able to use an elevator at an elite university, a university that is very much in the public eye and susceptible to public pressure, what must it takes workers around the country, in small factories and far-off hamlets, to secure more basic rights and privileges? This is a question I wish our academic theorists of democracy would think some more about.

Study Finds Grad Student Unions Actually Improve Things

From Inside Higher Ed:

The authors of a paper released this year surveyed similar graduate students at universities with and without unions about pay and also the student-faculty relationship. The study found unionized graduate students earn more, on average. And on various measures of student-faculty relations, the survey found either no difference or (in some cases) better relations at unionized campuses.

The paper (abstract available here) appears in ILR Review, published by Cornell University.

“These findings suggest that potential harm to faculty-student relationships and academic freedom should not continue to serve as bases for the denial of collective bargaining rights to graduate student employees,” says the paper, by Sean E. Rogers, assistant professor of management at New Mexico State University; Adrienne E. Eaton, a professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University; and Paula B. Voos, a professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers.

…

Much of the study focuses on student-faculty relations, and whether — as union critics fear — the presence of collective bargaining turns a mentoring relationship into an adversarial one. The graduate students were asked to respond to a series of statements about their professors as a measure of how they perceived their relationships. On many issues, there were not statistically significant differences. But on a number, the differences pointed to better relations at unionized campuses. Unionized graduate students were more likely than others to say their advisers accepted them as professionals, served as role models for them and were effective in their roles.

October 7, 2013

The only people who cared about literature were the KGB

Cornell historian Holly Case has a fascinating piece in The Chronicle Review on Stalin as editor. Reminds me of that George Steiner line that the only people in the 20th century who cared about literature were the KGB.

Here are some excerpts. But read the whole thing.

Joseph Djugashvili was a student in a theological seminary when he came across the writings of Vladimir Lenin and decided to become a Bolshevik revolutionary. Thereafter, in addition to blowing things up, robbing banks, and organizing strikes, he became an editor, working at two papers in Baku and then as editor of the first Bolshevik daily, Pravda. Lenin admired Djugashvili’s editing; Djugashvili admired Lenin, and rejected 47 articles he submitted to Pravda.

Djugashvili (later Stalin) was a ruthless person, and a serious editor. The Soviet historian Mikhail Gefter has written about coming across a manuscript on the German statesman Otto von Bismarck edited by Stalin’s own hand. The marked-up copy dated from 1940, when the Soviet Union was allied with Nazi Germany. Knowing that Stalin had been responsible for so much death and suffering, Gefter searched “for traces of those horrible things in the book.” He found none. What he saw instead was “reasonable editing, pointing to quite a good taste and an understanding of history.”

…

Stalin always seemed to have a blue pencil on hand, and many of the ways he used it stand in direct contrast to common assumptions about his person and thoughts. He edited ideology out or played it down, cut references to himself and his achievements, and even exhibited flexibility of mind, reversing some of his own prior edits.

…

For Stalin, editing was a passion that extended well beyond the realm of published texts. Traces of his blue pencil can be seen on memoranda and speeches of high-ranking party officials (“against whom is this thesis directed?”) and on comic caricatures sketched by members of his inner circle during their endless nocturnal meetings (“Correct!” or “Show all members of the Politburo”).

…

The Stanford historian Norman Naimark describes the marks left by Stalin’s pencil as “greasy” and “thick and pasty.” He notes that Stalin edited “virtually every internal document of importance,” and the scope of what he considered internal and important was very broad. Editing a biologist’s speech for an international conference in 1948, Stalin used an array of colored pencils—red, green, blue—to strip the talk of references to “Soviet” science and “bourgeois” philosophy. He also crossed out an entire page on how science is “class-oriented by its very nature” and wrote in the margin “Ha-ha-ha!!! And what about mathematics? And what about Darwinism?”

…

But Stalin was still not satisfied. In the next round of substantial edits, he used his blue pencil to mute the conspiracy he had previously pushed the authors to amplify (italics indicate an insertion):

The Soviet people unanimously approved the court’s verdict—the verdict of the people annihilation of the Bukharin-Trotsky gang and passed on to next business. The Soviet land was thus purged of a dangerous gang of heinous and insidious enemies of the people, whose monstrous villainies surpassed all of the darkest crimes and most vile treason of all times and all peoples.

October 5, 2013

David Grossman v. Max Blumenthal

Anyone familiar with Max Blumenthal’s journalism—in print or video (his interviews with Chicken Hawk Republicans are legendary)—knows him to be absolutely fearless. Whether he’s exploring the id of American conservatism or the contradictions of Israeli nationalism, Max heads deep into the dark places and doesn’t stop till he’s turned on all the lights.

Courage in journalism requires not only physical fortitude but also an especially shrewd and sophisticated mode of intelligence. It’s not enough to go into a war zone; you have to know how to size up your marks, not get taken in by the locals with their lore, and know when and how to squeeze your informants.

Max possesses those qualities in spades. With laser precision, he zeroes in on the most vulnerable point of his subjects’ position or argument—he reminds me in this respect of an analytical philosopher—and quietly and calmly takes aim. In academia, this can make people squirmy and uncomfortable; in politics, it makes them downright nasty and scary. But Max remains unflappable; he’s never fazed. And that, I think, is because he’s not interested in making people look foolish or absurd. He’s not a gonzo of gotcha. He’s genuinely interested in the truth, and knows that the truth in politics often lurks in those dark caves of viciousness.

Max’s new book Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel has just come out. It’s a big book, but it’s conveniently organized into short chapters, each a particular vignette capturing some element of contemporary Israeli politics and culture (not just on the right but across the entire society). I’m still reading it, but it’s the kind of book that you just open to any chapter and quickly get a sense of both the particular and the whole. You’ll find yourself instantly immersed in an engrossing family romance—one part tender, one part train-wreck—and wish you had the entire day to keep reading. Put it down, and pick it up the next day, and you’ll have the exact same feeling.

One chapter, in particular—”The Insiders”—has gotten into my head these past few weeks. It’s a portrait of David Grossman, the Israeli writer who’s often treated in this country as something of secular saint. Less arresting (and affected) than Amos Oz, the lefty Grossman was to Jews of my generation a revelatory voice, particularly during the First Intifada. But in the last decade, his brand of liberal Zionism has come to seem more of a problem than a solution.

I’ll admit I was skeptical when I first started reading the chapter because Grossman is not a typical subject for Max. He’s cagey, elusive, slippery. Max knows how to fell Goliath, I thought to myself, but can he get inside David? Turns out, he can.

Max begins his treatment of Grossman by setting out the conundrum of many lefty Israelis: like other liberal Zionists, Grossman thinks Israel’s original sin is 1967, when the state seized the West Bank and Gaza and the Occupation officially began. But that position ignores 1948, when Jewish settlers, fighters, and officials expelled Palestinians from their homes in order to create the State of Israel itself.

But notice how Max sets the table. Rather than rolling out the standard anti-Zionist party line, Max weaves in the voices of the Israeli right, creating a conversation of difficult contrapuntal voices. It makes for a wonderful, if excruciating, tension.

Despite his outrage at the misdeeds committed after 1967, Grossman excised the Nakba from his frame of analysis. Of course, he knew the story of Israel’s foundation, warts and all. But the Nakba was the legacy also of the Zionist left, as were the mass expulsions committed in its wake, and the suite of discriminatory laws passed through the Knesset to legalize the confiscation of Palestinian property. Were these the acts of an “enlightened nation?” By singling out the settlement movement as the source of Israel’s crisis, Grossman and liberal Zionists elided the question altogether, starting the history at 1967.

Though the Zionist left kept the past tucked behind the narrative of the Green Line, veterans of the Jabotinskyite right-wing were unashamed. In September 2010, when sixty actors and artists staged a boycott of a new cultural center in the West Bank–based mega-settlement of Ariel, earning a public endorsement from Grossman, who cast the boycott as a desperate measure to save the Zionist future from the settlers, they were angrily rebuked by Knesset chairman Reuven Rivlin.

A supporter of Greater Israel from the Likud Party, Rivlin was also a fluent Arabic speaker who rejected the Labor Zionist vision of total separation from the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza. (He appeared earlier in this book to defend Hanin Zoabi’s right to denounce Israel’s lethal raid of the Mavi Marmara against dozens of frothing members of Knesset.) Contradicting the official Israeli Foreign Ministry version of the Nakba, which falsely asserted that Palestinians “abandoned their homes…at the request of Arab leaders,” Rivlin reminded the liberal Zionists boycotting Ariel of their own history. Those who bore the legacy of the Nakba, Rivlin claimed, had stolen more than the settlers ever intended to take.

“I say to those who want to boycott—Deer Balkum [“beware” in Arabic]. Those who expelled Arabs from En-Karem, from Jaffa, and from Katamon [in 1948] lost the moral right to boycott Ariel,” Rivlin told Maariv. Assailing the boycotters for a “lack of intellectual honesty,” Rivlin reminded them that the economic settlers of Ariel were sent across the Green Line “due to the orders of society, and some might say—due to the orders of Zionism.”

Greater Israel had become the reality while the Green Line Israel had become the fantasy. But with the election of Barack Obama, a figure the Zionist left considered their great hope, figures like David Grossman believed that they would soon be released from their despair.

That line about Rivlin being a fluent Arabic speaker is a nice touch. But that line “those who bore the legacy of the Nakba, Rivlin claimed, had stolen more than the settlers ever intended to take” made me shiver.

Max managed to get an interview with Grossman in 2009 at a very difficult moment in Grossman’s life. Grossman’s son had been killed in the 2006 invasion of Lebanon, and he wasn’t giving interviews. But Max got one.

He opens his account of that encounter on a sympathetic note:

Grossman had told me in advance that he would agree to speak only off the record. But when I arrived at our meeting famished and soaked in sweat after a journey from Tel Aviv, he suddenly changed his mind. “Since you have come such a long way, I will offer you an interview,” he said. But he issued two conditions. First, “You must order some food. I cannot sit here and watch you starve.” And second, “No questions about my son, okay?”

Grossman was a small man with a shock of sandy brown hair and intense eyes. He spoke in a soft, low tone tinged with indignation, choosing his words carefully as though he were constructing prose. Though his Hebrew accent was strongly pronounced, his English was superior to most American writers I had interviewed, enabling him to reduce complex insights into impressively economical soundbites.

Max then moves the interview to politics, and you can feel his frustration with Grossman starting to build.

At the time, Grossman was brimming with optimism about Barack Obama’s presidency. Though the Israeli right loathed Obama, joining extreme rightists in the campaign to demonize him as a crypto-Muslim, a foreigner, and a black radical, liberal Zionists believed they had one of their own in the White House. Indulging their speculation, some looked to Obama’s friendship in Chicago with Arnold Jacob Wolf, a left-wing Reform rabbi who had crusaded for a two state solution during the 1970s before it was a mainstream position. If only Obama could apply appropriate pressure on Benjamin Netanyahu, still widely regarded as a blustering pushover, Israel could embark again on the march to the Promised Land, with the peace camp leading the tribe.

“This is the moment when Israel needs to see Likud come into contact with reality,” Grossman told me. “For years they have played the role of this hallucinating child who wants everything and asks for more and more. Now they are confronted with a harsh counterpoint by Mr. Obama, and they have to decide if they cooperate with what Obama says—a two-state solution—or continue to ask for everything.”

Grossman seemed confident that Obama was willing to confront Netanyahu, and that he would emerge victorious. “A clash with a strong and popular president is not possible for Israel. Israel can never, ever subjugate an American president,” he claimed. “I see Netanyahu reluctantly accepting the demands of Obama to enter into a two-state solution. [Netanyahu] will pretend to be serious about it, but he will do everything he can to keep the negotiations from becoming concrete. He will drag his feet, blame the Palestinians, and rely on the most extreme elements among the Palestinians to lash out in order to stop negotiations. My hope is that there is a regime in America that recognizes immediately the manipulation of the Likud government and that they won’t be misled.”

By the time Max poses a question about the US flexing its muscles over Israel, you know exactly what Grossman is going to say, and because of the way Max has set things up, you can see the combination of naivete and cynicism in Grossman’s position on full display.

I asked Grossman if Obama should threaten Netanyahu with the withholding of loan guarantees in order to loosen his intransigent stance, as President George H. W. Bush had done to force Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir (Netanyahu’s former boss) to the negotiating table. He rejected this idea out of hand. “I hope it shall be settled between friends,” Grossman responded. “The pressure Obama applies should be put in a sensitive way because of Israeli anxieties and our feeling that we’re living on the edge of an abyss. The reactions of Israelis are very unpredictable. It will take simple and delicate pressure for the United States to produce the results they are looking for. But whenever American presidents even hinted they were going to pressure Israel, they got what they wanted. Netanyahu is very ideological, but he is also realistic and he is intelligent, after all. He will recognize the reality he is in.”

Max doesn’t say anything, but you can see his eyes rolling in frustration and impatience (mine certainly were). Now he’s ready to get personal , to zoom in on the empty silence at the heart of Grossman’s position.

For Grossman and liberal Zionists like him, the transformation of Israel from an ethnically exclusive Jewish state into a multiethnic democracy was not an option. “For two thousand years,” Grossman told me when I asked why he believed the preservation of Zionism was necessary, “we have been kept out, we have been excluded. And so for our whole history we were outsiders. Because of Zionism, we finally have the chance to be insiders.”

I told Grossman that my father [Sidney Blumenthal] had been a kind of insider. He had served as a senior aide to Bill Clinton, the president of the United States, the leader of the free world, working alongside other proud Jews like Rahm Emanuel and Sandy Berger. I told him that I was a kind of insider, and that my ambitions had never been obstructed by anti-Semitism. “Honestly, I have a hard time taking this kind of justification seriously,” I told him. “I mean, Jews are enjoying a golden age in the United States.”

It was here that Grossman, the quintessential man of words, found himself at a loss. He looked at me with a quizzical look. Very few Israelis understand American Jews as Americans but instead as belonging to the Diaspora. But very few American Jews think of themselves that way, especially in my generation, and that, too, is something very few Israelis grasp. Grossman’s silence made me uncomfortable, as though I had behaved with impudence, and I quickly shifted the subject from philosophy to politics. Before long, we said goodbye, parting cordially, but not warmly. On my way out of the café, Grossman, apparently wishing to preserve his privacy, requested that I throw my record of his phone number away.

Like Blumenthal, you leave the interview feeling uncomfortable. Both at that anguished and abject confession from Grossman that Jews “finally have the chance to be insiders”—This is what all that brutality against the Palestinians was for? This is what Jews killed and were killed for? To be insiders?—and Blumenthal’s riposte that Jews outside Israel are insiders, too. Whether in Israel or at the highest levels of American power, that’s what we have become: insiders. That’s what Zionism means for us, whether we’re in Israel or without. We’re on the inside. The people of exile, the wandering Jew, has come home.

I’ve been sitting with that bleak exchange for days.

October 4, 2013

The Washington Post: America’s Imperial Scribes

Vo Nguyen Giap, the military leader of the Vietnamese resistance to French and American domination, has died. The Washington Post has a decent obituary, but this bit of language really caught my eye. Listen carefully to the different verbs that are used to describe the actions of the US versus those of the Vietnamese, post-Geneva Accords.

At the Geneva Conference that followed the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, Vietnam was divided into two countries: north and south. In the north, the Communist Party ruled under the leadership of Ho. With the French colonialists out of the picture, an ambitious land-reform program was undertaken, for which Gen. Giap would later apologize. “[W]e . . . executed too many honest people . . . and, seeing enemies everywhere, resorted to terror, which became far too widespread. . . . Worse still, torture came to be regarded as a normal practice,” he was quoted as having said by Neil Sheehan in his Pulitzer-winning 1988 book, “A Bright Shining Lie.”

In the south, the United States replaced France as the major foreign influence. CIA operatives worked to blunt communist initiatives, and by the early 1960s, U.S. soldiers began arriving as “advisers” to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Men and supplies flowed southward from Hanoi, and indigenous guerrilla units throughout South Vietnam began raiding government troops and installations. The United States increased its level of support, which by 1968 had reached 500,000 military personnel.

So in 1954, Vietnam was merely “divided.” By no one. In the North, the Communists “ruled,” “executed” innocents, and “tortured.” In the South, the US merely “replaced” France as an “influence.” The CIA “worked,” American soldiers “arrived,” supplies “flowed,” the US “increased support.”

Sixty years later, America’s imperial scribes are still at the top of their game.

October 3, 2013

Mark Zuckerberg, Meet George Pullman

Facebook Inc.’s sprawling campus in Menlo Park, Calif., is so full of cushy perks that some employees may never want to go home. Soon, they’ll have that option.

The social network said this week it is working with a local developer to build a $120 million, 394-unit housing community within walking distance of its offices. Called Anton Menlo, the 630,000 square-foot rental property will include everything from a sports bar to a doggy day care.

…

One of Facebook’s corporate goals is to take care of as many aspects of its employees lives as possible. They don’t have to worry about transportation—there’s a bus for that. Laundry and dry cleaning? Check. Hairstylists, woodworking classes, bike maintenance. Check.

Michael Walzer, Spheres of Justice:

Pullman, Illinois, was built on a little over four thousand acres of land along Lake Calumet just south of Chicago…The town was founded in 1880 and substantially completed, according to a single unified design, within two years. [George] Pullman…didn’t just put up factories and dormitories, as had been done in Lowell, Massachusetts, some fifty years earlier. He built private homes, row houses, and tenements for some seven to eight thousand people, shops and offices (in an elaborate arcade) schools, stables, playgrounds, a market, a hotel, a library , a theater, even a church: in short, a model town, a planned community.

And every bit of it belonged to him.

Back to the future.

Adam Smith on the Mobility of Labor v. Capital

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book I, Chapter 10, Part II:

Corporation laws, however, give less obstruction to the free circulation of stock from one place to another than to that of labour. It is everywhere much easier for a wealthy merchant to obtain the privilege of trading in a town corporate, than for a poor artificer to obtain that of working in it.

Same as it ever was.

October 2, 2013

Adam Smith Was Never an Adjunct

Every single one of the explanations that Adam Smith offers—in Book 1, Chapter 10, Part 1, of The Wealth of Nations—for the difference in wage rates between various kinds of labor is discomfirmed by the example of adjuncts in the academy.*

Turns out: work that is harder, more disagreeable, more precarious, riskier as a long-term career opportunity, of lower social standing, and that requires more time and training to enter into and more trust from society to perform, does not in fact pay better.

*These explanations have to do with what Smith calls “inequalities arising from the nature of the employments themselves.” These explanations are to be distinguished from those having to do with government policies or the forces of supply and demand.

September 30, 2013

The History of Fear, Part 4

Today, in part 4 of our series on the intellectual history of fear, we turn to Hannah Arendt’s theory of total terror, which she developed in The Origins of Totaltarianism (and then completely overhauled in Eichmann in Jerusalem.)

I’m more partial, as I make clear in my book, to Eichmann than to Origins. But Origins has always been the more influential text, at least until recently.

It’s a problematic though fascinating book (the second part, on imperialism, is especially wonderful). But one of the reasons it was able to gain such traction is that it managed to meld Montesquieu’s theory of despotic terror with Tocqueville’s theory of democratic anxiety. It became the definitive statement of Cold War social thought in part because it took these received treatments and mobilized them to such dramatic effect. (And one of the reasons, I further argue in the book, that Eichmann provoked such outrage was that it revived some of the ways of thinking about fear that we saw in Hobbes.)

Again, if you want to get the whole picture, buy the book.

• • • • •

Mistress, I dug upon your grave

To bury a bone, in case

I should be hungry near this spot

When passing on my daily trot.

I am sorry, but I quite forgot

It was your resting-place.

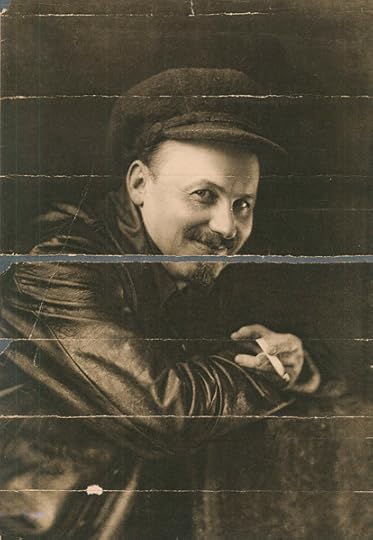

It was a sign of his good fortune—and terrible destiny—that Nikolai Bukharin was pursued throughout his short career by characters from the Old Testament. Among the youngest of the “Old Bolsheviks,” Bukharin was, in Lenin’s words, “the favorite of the whole party.” A dissident economist and accomplished critic, this impish revolutionary, standing just over five feet, charmed everyone. Even Stalin. The two men had pet names for each other, their families socialized together, and Stalin had Bukharin stay at his country house during long stretches of the Russian summer. So beloved throughout the party was Bukharin that he was called the “Benjamin” of the Bolsheviks. If Trotsky was Joseph, the literary seer and visionary organizer whose arrogance aroused his brothers’ envy, Bukharin was undoubtedly the cherished baby of the family.

Nikolai Bukharin

Not for long. Beginning in the late 1920s, as he sought to slow Stalin’s forced march through the Russian countryside, Bukharin tumbled from power. Banished from the party in 1937 and left to the tender mercies of the Soviet secret police, he confessed in a 1938 show trial to a career of extraordinary counterrevolutionary crime. He was promptly shot, just one of the 328,618 official executions of that year.

Not long before his murder, Bukharin invoked a rather different biblical parallel to describe his fate. In a letter to Stalin, Bukharin recalled the binding of Isaac, the unwitting son whose father, Abraham, prepares him, on God’s instruction, for sacrifice. At the last minute, an angel stops Abraham, declaring, “Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me.” Reflecting upon his own impending doom, however, Bukharin envisioned no such heavenly intervention: “No angel will appear now to snatch Abraham’s sword from his hand.”

The biblical reference, with its suggested equivalence of Stalin and Abraham, was certainly unorthodox. But in the aftermath of Bukharin’s execution it proved apt, for no other crime of the Stalin years so captivated western intellectuals as the blood sacrifice of Bukharin. It was not just that this darling of the communist movement, “the party’s most valuable and biggest theoretician,” as Lenin put it, had been brought down. Stalin, after all, had already felled the far more formidable Trotsky. It was that Bukharin confessed to fantastic crimes he did not commit.

For generations of intellectuals, Bukharin’s confession would symbolize the depredations of communism, how it not only murdered its favored sons, but also conscripted them in their own demise. Here was an action, it seemed to many, undertaken not for the self, but against it, on behalf not of personal gain, but of self-destruction. Turning Bukharin’s confession into a parable of the entire communist experience, Arthur Koestler, in his 1941 novel Darkness at Noon, popularized the notion—later taken up by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Humanism and Terror and Jean-Luc Godard in his 1967 film La Chinoise—that Bukharin offered his guilt as a final service to the party. In this formulation it was not Stalin, but Bukharin, who was the true Abraham, the devout believer who gave up to his jealous god that which was most precious to him.

But where Abraham’s readiness to make the ultimate sacrifice has aroused persistent admiration—Kierkegaard deemed him a “knight of faith,” prepared to violate the most sacred of norms for the sake of his fantastic devotion—Bukharin’s has provoked almost universal horror. Not just of Stalin and the Bolshevik leadership, but of Bukharin himself—and of all the true believers who turned the twentieth century into a wasteland of ideology.

Sacrifice of Isaac

Moralists may praise familiar episodes of suicidal sacrifice such as the Greatest Generation storming Omaha Beach, but the willingness of the Bukharins of this world to give up their lives for the sake of their ideology remains, for many, the final statement of modern self-abasement. Not because the sacrifice was cruel or senseless—not even because it was undertaken for an unjust cause or was premised on a lie—but because of the selfless fanaticism and political idolatry, the thoughtless immolation and personal diminution, that are said to inspire it. Communists, the argument goes, collaborated in their own destruction because they believed; they believed because they had to; they had to because they were small.

According to Arthur Schlesinger, communism “fills empty lives”—even in the United States, with “its quota of lonely and frustrated people, craving social, intellectual and even sexual fulfillment they cannot obtain in existing society. For these people, party discipline is no obstacle: it is an attraction. The great majority of members in America, as in Europe, want to be disciplined.” Or, as cultural critic Leslie Fiedler wrote of the Rosenbergs after their execution, “their relationship to everything, including themselves, was false.” Once they turned into party liners, “blasphemously den[ying] their own humanity,” “what was there left to die?” Abraham believed in his faith and was deemed a righteous man; the communist believed in his and was discharged from the precincts of humanity.

As we now know, Bukharin’s confession, like so many others of the Stalin era, was not quite the abnegation intellectuals have imagined. From 1930 to 1937, Bukharin resisted, to the best of his abilities, the more outlandish charges of the Soviet leadership. As late as his February 1937 secret appearance before the Plenum of the Central Committee, Bukharin insisted, “I protest with all the strength of my soul against being charged with such things as treason to my homeland, sabotage, terrorism, and so on.” When he finally did admit to these crimes—in a public confession, replete with qualifications casting doubt upon Stalin’s legitimacy—it was after a yearlong imprisonment, in which he was subject to brutal interrogations and threats against his family.

Bukharin had reason to believe that his confession might protect him and his loved ones. Soviet leaders who confessed were sometimes spared, and Stalin had intervened on previous occasions to shield Bukharin from more vicious treatment. Threats against family members, moreover, were one of the most effective means for securing cooperation with the Soviet regime; in fact, many of those who refused to confess had no children. Instead of manic self-liquidation, then, Bukharin’s confession was a strategic attempt to preserve himself and his family, an act not of selfless fanaticism but of self-interested hope.

But for many intellectuals at the time, these calculations simply did not register. For them, the archetypical evil of the twentieth century was not murder on an unprecedented scale, but the cession of mind and heart to the movement. Reading the great midcentury indictments of the Soviet catastrophe—Darkness at Noon, The God That Failed, 1984, The Captive Mind—one is struck less by their appreciation of Stalinist mass murder—it would be years before Solzhenitsyn turned the abstraction of the gulag into dossiers of particular suffering—than by their horror of the liquidated personality that was supposed to be the new Soviet man. André Gide noted that in every Soviet collective he visited “there are the same ugly pieces of furniture, the same picture of Stalin and absolutely nothing else—not the smallest vestige of ornament or personal belonging.” (Writers consistently viewed public housing, whether in the Soviet Union or in the United States, as a proxy for leftist dissolution. Fiedler, for instance, made much of the fact that the Rosenbergs lived in a “melancholy block of identical dwelling units that seem the visible manifestation of the Stalinized petty-bourgeois mind: rigid, conventional, hopelessly self-righteous.”) Perversely taking Stalin at his word—that a million deaths was just a statistic—intellectuals concluded that the gulag, or Auschwitz, was merely the outward symbol of a more profound, more ghastly subtraction of self. Even in the camps, Hannah Arendt wrote, “suffering, of which there has been always too much on earth, is not the issue, nor is the number of victims.” It was instead that the camps were “laboratories where changes in human nature” were “tested” and “the transformation of human nature” engineered for the sake of an ideology.

If we owe any one thinker our thanks, or skepticism, for the notion that totalitarianism was first and foremost an assault, inspired by ideology, against the integrity of the self, it is most assuredly Hannah Arendt. A Jewish German émigré to the United States, Arendt was not the first to make such claims about totalitarianism. But by tracing the ideologue’s self-destruction against a backdrop of imperial misadventure and massacre in Africa, waning aristocracies and dissolute bourgeoisies in Europe, and atomized mass societies throughout the world, Arendt gave this vision history and heft. With a cast of characters—from Lawrence of Arabia and Cecil Rhodes to Benjamin Disraeli and Marcel Proust—drawn from the European landscape, Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism made it impossible for anyone to assume that Nazism and Stalinism were dark emanations of the German soil or Russian soul, geographic accidents that could be ascribed to one country’s unfortunate traditions. Totalitarianism was, as the title of the book’s British edition put it, “the burden of our times.” Not exactly a product of modernity—Arendt repeatedly tried to dampen the causal vibrato of her original title, and she was as much a lover of modernity as she was its critic—but its permanent guest.

Hannah Arendt

Yet it would be a mistake to read The Origins of Totalitarianism as a transparent report of the totalitarian experience. As Arendt was the first to acknowledge, she came to the bar of political judgment schooled in “the tradition of German philosophy,” taught to her by Heidegger and Jaspers amid the crashing edifice of the Weimar republic. Making her way through a rubble of German existentialism and Weimar modernism, Arendt gave totalitarianism its distinctive cast, a curious blend of the novel and familiar, the startling and self-evident. Arendt’s would become the definitive statement—so fitting, so exact—not because it was so fitting or exact, but because it mixed real elements of Stalinism and Nazism with leading ideas of modern thought: not so much twentieth-century German philosophy, as we shall see, but the notions of terror and anxiety Montesquieu and Tocqueville developed in the wake of Hobbes. As Arendt confessed in private letters, she discovered “the instruments of distinguishing totalitarianism from all—even the most tyrannical—governments of the past” in Montesquieu’s writings, and Tocqueville, whose work she read while drafting The Origins of Totalitarianism, was a “great influence” on her.

But within a decade of publishing The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt changed course. After traveling to Israel in 1961 to report on the trial of Adolph Eichmann for The New Yorker, she wrote Eichmann in Jerusalem, which turned out to be not a trial report at all, but a wholesale reconsideration of the dynamics of political fear. Not unlike Montesquieu’s Persian Letters or the first half of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, Eichmann in Jerusalem posed a direct challenge to the account of fear that had earned its author her greatest acclaim. It produced a storm of outrage, much of it focused on Arendt’s depiction of Eichmann, her savage sense of irony, and her criticism of the Jewish leadership during the Holocaust. But an allied, if unspoken, source of fury was the widespread hostility to Arendt’s effort to upend the familiar canons of political fear: for in Eichmann, Arendt showed that much that Montesquieu and Tocqueville—and she herself—had written about political fear was simply false, serving the political needs of western intellectuals rather than the truth. Arendt paid dearly for her efforts. She lost friends, was deemed a traitor to the Jewish people, and was hounded at public lectures. But it was worth the cost, for in Eichmann Arendt managed “a paean of transcendence,” as Mary McCarthy put it, offering men and women a way of thinking about fear in a manner worthy of grown-ups rather than children. That so many would reject it is hardly surprising: little since Hobbes had prepared readers for the genuine novelty that was Eichmann in Jerusalem. Forty years later, we’re still not prepared.

Victims of the Great Purge

If Hobbes hoped to create a world where men feared death above all else, he would have been sorely disappointed, and utterly mystified, by The Origins of Totalitarianism. What could he possibly have made of men and women so fastened to a political movement like Nazism or Bolshevism that they lacked, in Arendt’s words, “the very capacity for experience, even if it be as extreme as torture or the fear of death?” Hobbes was no stranger to adventures of ideology, but his ideologues were avatars of the self, attracted to ideas that enlarged them. Though ready to die for their faith, they hoped to be remembered as martyrs to a glorious cause. For Arendt, however, ideology was not a statement of aspiration; it was a confession of irreversible smallness. Men and women were attracted to Bolshevism and Nazism, she maintained, because these ideologies confirmed their feelings of personal worthlessness. Inspired by ideology, they went happily to their own deaths—not as martyrs to a glorious cause, but as the inglorious confirmation of a bloody axiom. Hobbes, who worked so hard to reduce the outsized heroism of his contemporaries, would hardly have recognized these ideologues, who saw in their own death a trivial chronicle of a larger truth foretold.

What propelled Arendt in this direction, away from Hobbes? Not the criminal largesse of the twentieth century—she repeatedly insisted that it was not the body counts of Hitler and Stalin that distinguished their regimes from earlier tyrannies—but rather a vision, inherited from her predecessors, of the weak and permeable self. Between the time of Hobbes and that of Arendt, the self had suffered two blows, the first from Montesquieu, the second from Tocqueville. Montesquieu never contemplated the soul-crushing effects of ideology, but he certainly imagined souls crushed. It was he who first argued, against Hobbes, that fear, redefined as terror, did not enlarge but reduce the self, and that the fear of death was not an expression of human possibility but of desperate finality. Tocqueville retained Montesquieu’s image of the fragile self, only he viewed its weakness as a democratic innovation. Where Montesquieu had thought the abridged self was a creation of despotic terror, Tocqueville believed it was a product of modern democracy. The democratic individual, according to Tocqueville, lacked the capacious inner life and fortified perimeter of his aristocratic predecessor. Weak and small, he was ready for submission from the get-go. So strong was this conviction about the weakness of the modern self that Arendt was able to apply it, as we shall see, not only to terror’s victims but, even more wildly, to its wielders as well.

Melding Montesquieu’s theory of despotic terror and Tocqueville’s account of mass anxiety, Arendt turned Nazism and Stalinism into spectacular triumphs of antipolitical fear, what she called “total terror,” which could not “be comprehended by political categories.” Total terror, in her eyes, was not an instrument of political rule or even a weapon of genocide. One will look in vain throughout the last third of The Origins of Totalitarianism, where Arendt addresses the problem of total terror, for any reckoning with the elimination of an entire people. Total terror, for Arendt, was designed to escape the psychological burdens of the self, to destroy individual freedom and responsibility. It was a form of “radical evil,” which sought to eradicate not the Jews or the kulaks but the human condition. If Arendt’s totalitarianism constituted an apotheosis, it was not of human beastliness. It was of a tradition of thought—established by Montesquieu, elaborated by Tocqueville— that had been preparing for the disappearance of the self from virtually the moment the self had first been imagined.

Yes, You Can Be Fired for Liking My Little Pony

My Little Pony

My daughter loves My Little Pony. So does this guy. And that, apparently, is a problem. Grown men are not supposed to like the same things as young girls.

The guy—though Gawker has done a story on him, he remains anonymous—is a dad in his late 30s. He calls himself “a fairly big fan.” He made the picture of one of the show’s characters the background image on his desktop. He talked to the boss’s 9-year-old daughter about the show. His co-workers, and the boss, got freaked out. According to the guy, the boss told him that “it’s weird and it makes people uncomfortable that I have a ‘tv show for little girls as a background.’”

Now he’s been fired.

After talking to several folks, I’m still not clear why people are freaked out by this guy. Is it the gender non-comformity? If so, you better revise your sense of what’s normal because, as the Washington Post reports, an increasing number of dudes are loving the show. There’s even a FB page called “The Christian Libertarian Brony.” (The creator of the page writes: “On this page I post stuff about Austrian economics, Christian libertarianism/Christian anarcho-capitalism, MLP:FiM & GMOs!”)

Or is it the hint of pedophilia? If so, would you be nervous if a grown man had a passion for Little League or superhero comics? Enough to fire him?

Others have told me it’s the Peter Pan syndrome: guys like this just seem like they’ve never grown up. Unlike, apparently, every other dude on the internet.

Regardless of what buttons are being set off by this guy, the story just confirms a point some of us have been making over and over again: the American workplace is one of the most coercive institutions around. It’s a place where, whatever the niceties and pieties of our allegedly tolerant culture may be, bosses and supervisors get to act out—and on—their most regressive anxieties and fears. It’s a playground of cultural and political recidivism, where men and women (but more often men) are given the tools to inflict and enforce their beliefs, their style, their values upon their employees.

Chris Bertram, Alex Gourevitch, and I have tried to use these extreme cases to point to a more systemic underlying problem of power and domination in the workplace. It’s not merely that bosses are intolerant assholes, though clearly many of them are. It’s that they get to be intolerant assholes because the workplace is set up that way. Not by accident, or in the exception, but by design. In the typical American workplace, you can be fired for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reason at all. By law.

And so we come back to the Gawker piece. As Nathan Newman pointed out to me, every time a story like this comes out, there’s a frenzy of commentary, where people wonder whether or not this kind of thing is illegal, why doesn’t the employee sue, and so on. Most people seem to think that First Amendment-ish freedoms—the freedom of not merely speech but of expression, of personal style, etc.—apply in the workplace. They don’t. And while there are a host of protections for protected categories of workers, those constitute a limited number of cases.* The vast majority of cases of workplace coercion are simply not covered by federal or state law (though see this article by Eugene Volokh for a counterpoint; his focus, however, is on exclusively political speech). Unless you have a union, which ensures that you can only be fired for just cause, you’re often screwed.

Here’s the bottom line: in most American workplaces, the boss can fire any brony who loves My Little Pony. It’s totally legal. And that’s the problem.

* I asked Nathan, who’s an expert on labor and employment law, whether or not this guy could make some kind of claim based on gender discrimination, i.e., that he was fired for being insufficiently masculine, along the lines of a woman claiming she was fired for being insufficiently feminine. Here’s what he wrote back:

That’s the only plausible argument but few lawsuits on that basis have been successful, even for women arguing they are insufficiently feminine—unless they can show it’s part of an overall bias against women in general. But where no clear bias against women and men in hiring and promotion, differential dress codes and other biases based on gender that do not burden their performance of work would generally be legal. That’s one reason why state (and ideally federal) gay and transgender anti-discrimination laws are needed.

He then sent me to this article—“Sexual Orientation, Gender Nonconformity, and Trait-Based Discrimination: Cautionary Tales From Title VII & An Argument for Inclusion”—by Angela Clements from the Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law and Justice, which I have not yet read.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers