Hannah Byron's Blog, page 7

May 16, 2023

Hello Reader

Welcome to Historical Facts & Fiction. Here imagination meets reality. I created this blog as a space to assemble my own research that had no place in my World War novels. I hope you’ll enjoy finding out more about the background to The Resistance Girl Series.

Titbits of research certainly have their place in historical fiction, but when it becomes info dump, it’s too much. But in a blog there’s enough space to share all in-depth investigations and fieldwork to my heart’s content.

Most Historical Fiction readers are fervent researchers themselves; half the fun of reading a good HF novel is popping onto the net to fact-check what you’ve just read. You simply must know if SOE really had women spies, or if Eva Braun actually married Hitler hours before joining him in death. The internet is our treasure trove. I know I can’t stop myself, and love learning a thing or two in the process.

Have you ever wondered where HF authors get their ideas for a new book or series, or how they do their research? No two HF authors are alike – of course – but we all do rely heavily on today’s search engines. No work gets done without it.

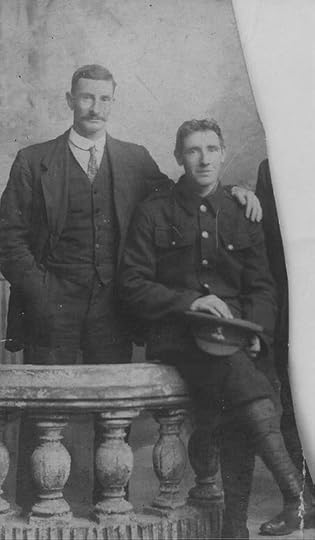

However, as you’ll read in an upcoming blog post, my reason for starting The Resistance Girl Series was a family photo I found by chance. Curiosity is a good start. As a European with lineage in several countries, I not only study the lives of these people. They are in my bloodline.

My Great-uncles William and Jack Westcott

But it wasn’t just my uncles’ photograph that incited me to write In Picardy’s Fields. It may sound terrible to say - and I won’t do so aloud - but I love the World Wars. For me as a fiction writer these intense and dark periods in recent human history provide the greatest canvas on which to splash my stories, in an endless variety; this was the period – par excellence – in which ordinary people performed extraordinary deeds. And we all love us a decent hero(ine)!

I’m never tired of learning more about the first half of the 20th century and how it’s shaped our current society. So, please permit me to infect you with some of that passion.

Next to online studies, you can also join me on my field trips to various countries while I do my onsite research.

On to the first blog now…

Thank you for being here!

April 22, 2023

The Dilemma of the Jewish Council in Holland during WW2

Amsterdam, November 1942. Meeting of the executive board of the Jewish Council. From left to right Meyer de Vries, J. Brandon, the chairmen A. Asscher and Prof. D. Cohen, A. van der Laan. Image bank WW2 / NIOD, Joh. De Haas

In the trilogy of blogs on why Holland suffered the highest number of Jewish victims per capita in the Holocaust, I briefly touched on the position of “De Joodsche Raad (the Jewish Council) in this context.

The Jewish Council was established by order of the Germans in 1941 and was the Jewish organization instructed to ‘manage the Jewish community in the Netherlands during the war’. Through the Council, the occupier issued orders to the Jewish community. As a result, the members of the Jewish Council were faced with major dilemmas.

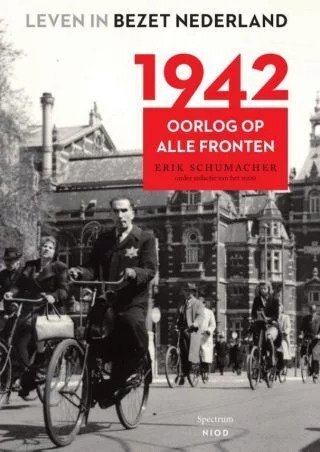

The final words to what extent this Council was half-guilty or not of collaboration with the German occupiers will probably never be fully answered, but in 1917 researcher Erik Schumacher touched extensively on this delicate matter in his (Dutch) book: ‘1942. Oorlog op Alle Fronten’ (1942 – War on all Fronts).

I’ve translated an article that gives a summary of Schumacher’s chapters on the Jewish Council as I believe it will give you the best idea of the dilemmas and time-bound restrictions the Council was faced with.

Essenburgsingel 24, Rotterdam, 1 July 1942

The local representatives of the Jewish Council are in session. The main representative in Rotterdam, Dr. Hendrik Cohen (no relation to chairman David Cohen) was in Amsterdam that morning, where he was instructed by the national leadership of the Jewish Council. He is now reporting to his staff. He has been told that the occupier will soon send the first calls for the deportation of Jews to labor camps in Germany. Employees of the Jewish Council are exempt from departure. However, the Jewish Council will have to assist with the registration of those summoned.

Those present at the meeting are settling into the bad news. They ask practical questions about how many have to leave and when, and about what is known about the labor camps.

Then representative Mr. M.J. Pool asks to speak. He’s furious. He says the Jewish Council has become “a wry joke.” According to Pool, the employees are asked to keep a device running “that is aimed at nothing but to lead ourselves to slaughter.” “Isn't it time,” he asks, “to finally say a firm NO to the occupation?”

The Council in Amsterdam

On Friday evening, June 26, chairman Cohen of the Jewish Council is summoned to the Zentralstelle in Amsterdam for a meeting with Aus der Fünten. Hauptsturmführer Ferdinand aus der Fünten is the informal leader of the German body responsible for carrying out the deportations, the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung.

Hauptsturmführer Ferdinand aus der Fünten (right) sitting next to the commander of camp Westerbork, A. Gemmeker, during the celebration of Christmas 1942 in the Durchgangslager. Image bank WO2 / NIOD

Cohen’s co-chairman, Abraham Asscher, has not come along expecting only administrative matters would be on the agenda. How radically different the real circumstances of the meeting turn out to be. Aus der Fünten coldly announces that a start will soon be made with sending Jews for ‘labor deployment under police supervision’ to Germany. The Jewish Council will be responsible for their registration. The next day, Cohen is expected to specify how many people the Jewish Council will be able to register on a daily basis.

“We were, of course, extremely upset by this entirely unexpected announcement,” Cohen later wrote in his memoirs. In his memory, he protested vehemently and threatened to resign momentarily. Aus der Fünten assured him that ‘very many’ Jews would remain in the Netherlands. The rest would have to work in Germany, but under liveable conditions.

The next morning, Cohen repeats Aus der Fünten’s announcement at an emergency meeting of the Jewish Council. Opinions vary widely. Some members refuse all cooperation. They reject the argument the Jewish Council should seize the opportunity to influence exemptions: the Council is in place to represent the interests of all Jews, not to determine which Jews are more important or valuable than the rest.

Others argue that the occupiers will go about their business anyway. By cooperating, the Jewish Council can at least buy time. That isn’t a negligible consideration, given the fact the Allies announced a second front in Europe two weeks earlier. Who knows, maybe the Netherlands will be liberated by the end of the summer. Moreover, if the Jewish Council were to influence the exemptions, it could protect people who would be of great importance for the reconstruction of the Jewish community after the liberation – in silence, of course, the members also count themselves among that group. And for those who would not receive an exemption, the Jewish Council would take care. They would be much worse off if they were left entirely to the cruel Germans.

The Assembly votes in favor of cooperation by a majority. The opponents resign themselves to their defeat. They remain members of the Council.

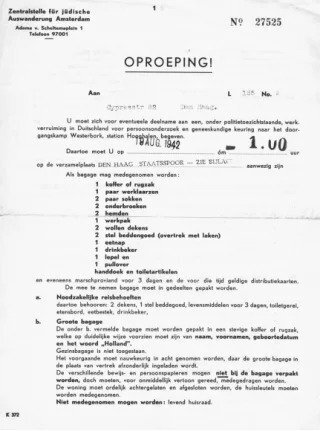

For the call Jews received this letter (in Dutch) exactly how much luggage may be taken to the labor camps. Image bank WW2 / NIOD

Thus, on the morning of June 27, the Jewish Council crosses another line. The occupier has constantly pushed the Council’s boundaries and each time it has yielded. The low point that it’s now reached was unimaginable at the beginning of the occupation. To prevent worse, the Council decides it is permissible to cooperate in the deportation of possibly tens of thousands of Dutch Jews to camps abroad.

This far-reaching decision not only means assistance in the registration of deportees, but also that the Jewish Council will manage the Hollandse Schouwburg (where the deportees are assembled) and continue to distribute the Germans’ ordinances and threats in Het Joodsche Weekblad, (The Jewish Weekly Newspaper) printed alongside calls for obedience. It is this basic attitude of submission that will not change in the rest of the war, no matter how many promises the occupier is to break, and no matter how many signals arrive that ‘labor deployment’ is just a euphemism for a terrible truth.

The Deception

On 30 June, two weeks before the start of the deportations, Cohen is back at Aus der Fünten on the Zentralstelle, this time with Asscher to ask for clarification. The previous evening, the newspapers carried a disturbing report. ‘Generalkommissar Schmidt takes a stand against Jews,’ wrote the Algemeen Handelsblad (National Dutch Newspaper). In a speech to departments of the NSB and NSDAP, Schmidt had taken an advance on the imminent deportation of the Dutch Jews.

“They will return there just as poor, whence they came,”

... the newspaper quoted him — a reference to the myth that the Jews of Western Europe all had their origins in Eastern Europe.

“Anyone who still sympathizes with Judaism will be treated on an equal footing.”

(Fritz Schmidt was the German Commissioner-General for Political Affairs and Propaganda in the occupied Netherlands between 1940 and 1943, one of four assistants to the Governor-General, Arthur Seyss-Inquart.)

Jews read the message with great dismay. Although Cohen already knows more about what is to come, he too is shocked. Aus der Fünten had promised him that ‘very many’ Jews would stay in the Netherlands. From Schmidt’s words, something quite different could be read: every Jew will have to go East. Cohen presents this interpretation to Aus der Fünten. The German doesn’t ignore the fact that in the long run it is indeed the intention that all Jews leave the Netherlands. ‘But,’ he hisses, ‘that will not be easy’. He promises that a few groups, including the employees of the Jewish Council, will not have to worry for the time being. To underline the innocent nature of labor in Germany, he promises correspondence between the Netherlands and the labor camps. Sufficiently reassured, Cohen and Asscher return home.

Two weeks later, the first train leaves Westerbork for Auschwitz. To his dismay, Cohen learns from eyewitnesses that it has been a freight train.

“I thought that if the deportations took place in this way, labor could not possibly be the end goal,” he would remember later.

Cohen goes back to the Zentralstelle and tells Aus der Fünten that “it was proof to me that the Jews were not sent to the East to work, but that they would be abscorned.” Aus der Fünten, according to Cohen, is “very impressed” by his emotional speech and tells him he’ll investigate the matter immediately. The same day, Cohen is called back to the Zentralstelle. He is told that his complaint is duly noted. That there will be no question of abschlachten and that from now on passenger trains will be used for the transports. Cohen contents himself with this answer.

And this is how it goes every time: Cohen protests but allows himself to be convinced again. Aus der Fünten knows how to play him sublimely. All the Haupfsturmführer wants is to continue to work with the Jewish Council to ensure the deportations take place as orderly as possible.

To manipulate Cohen, he always plays three trump cards. He intimidates him by threatening much stricter measures if the Jewish Council doesn’t cooperate, he placates him with privileges for his employees and with the power to remove names from deportation lists and – perhaps most importantly – he misleads the Jewish chairman. To maintain order, Jews must be left under the delusion that there is hope up to the threshold of death.

Aus der Fünten deceives Cohen by creating the illusion of a negotiating space. He always demands more from the Jewish Council than he needs, so that he can later ‘meet’ Cohen’s objections and make him feel the Council has managed to prevent worse. He makes concessions, often for supposedly humanitarian reasons, which he has no intention of ever fulfilling.

And he also deceives the chairman by insisting the Jews are being taken away to make themselves useful as laborers. That myth is an essential part of the plans worked out at the top of the Third Reich after the Wannsee Conference (a meeting of senior government officials of Nazi Germany and Schutzstaffel leaders, held in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee on 20 January 1942).

During this conference it is decided that to maintain order, Jews must be left under the delusion that there is hope up to the threshold of death. The extensive baggage instructions issued by the Amsterdam Zentralstelle also circulates in other occupied territories to perpetuate the fiction that the Jews are sent to real labor camps.

The Briefaktion

The Briefaktion serves the same deception goal, possibly devised by Eichmann himself. Prisoners in extermination camps are forced to write home that life is fine. Even as they undress in front of the shower room that will actually turn out to be a gas chamber — the ultimate façade — they write “Es geht mir gut” on cards. Such postcards also reach the Jewish Council in Amsterdam.

Cohen often dismisses rumors of mass murder in the camps as propaganda. He and his associates take the postcards for real. Is it because this suits their own actions? Is it hoping against their better judgment? The favorable reports from the camps are posted in Het Joodsche Weekblad. They also form the basis of a report that a branch of the Jewish Council draws up at the end of September on ‘The Jews in German labor camps’. The food is reportedly adequate, the sick are well cared for and the treatment of the workers is generally correct. In short, the preliminary conclusion is that positive: “That a healthy man can endure the stay in these camps without risk to life or health.”

In the minutes of a meeting of the Jewish Council that took place around the same time, there is one sentence that sticks out like a sore thumb:

‘Unfortunately, an obituary has been received of a Jew born in 1905, from Auschwitz in Silesia.’

One obituary. At least 10,000 could have been sent to the Netherlands by then.

P.S. Both Abraham Asscher en David Cohen survived WW2.

Book (in Dutch): “1942. War on all Fronts” by Erik Schumacher

The Jewish deportations in Amsterdam and the help from local Dutch people is at the core of my upcoming novel The Crystal Butterfly. Coming 6 July. Now on preorder.

April 16, 2023

Why did Holland have the highest number of Jewish victims during WW2. Part 3

Three Jewish brothers hiding in a barn in rural Holland

In the first blog post, I explained the differences between Holland, Belgium, and France regarding their Jewish populations and the governments that were put into place after the German occupation in 1940. In the second post, I explored the Dutch situation in more depth.

In part 3 we get the answer why Holland had the highest number of Jewish victims per capita.

My next book in The Resistance Girl Series, The Crystal Butterfly, which comes out on 6 July, is based on a fictive story of the lamentable Jewish situation in Holland during World War Two.

Deportations in the Netherlands

When deportations began in all three countries in July 1942, it turned out that the German police in the Netherlands had almost complete control over these transports, largely outside the rest of the occupation administration and the Dutch authorities. This was to a lesser extent the case in Belgium and did not apply to France. For the Dutch situation it meant the Germans extensively used deception to execute the deportations. For example, they provided tens of thousands of provisional exemptions (a so-called Sperre), only to withdraw them step by step later.

All Dutch Jews had been meticulously registered in a chart room. Tragically, with the help of the data the Joodsche Raad (Jewish Council) had collected. This allowed the Germans to take apart parts of Dutch Jewry without resistance or much hiding.

The German police managed to remove the Jewish population without this leading to much hiding or resistance. The Germans called this secret rounding up in stages Stufe Nacht und Nebel (Operation Night and Fog). Adolf Eichmann, who organized the deportations of the Jews throughout Europe from Berlin, was satisfied and spoke these horrific words: the trains from the Netherlands 'rollten am Anfang, dass man sagen kann, es war eine Pracht' ('rolled in the beginning, that one can say, it was beautiful').

From January 1942, an increasing number of Jewish men had been sent to labor camps within the Netherlands. When the deportations started in July of that year, these men thought they wouldn’t have to go to Poland, as they were already employed. In early October 1942, these men, together with their families, (over 12,000 people) were arrested in one big razzia and almost all of them directly deported to Auschwitz.

The same was true for the Jewish hospitals, orphanages, and homes for the elderly. Apparently, being left alone by the German police for months, many believed they were still safe. From January 1943 onwards, these places were evacuated one after the other. As with the labor camps, these groups were an easy prey for the occupiers because of isolation and concentration beforehand.

In 1942, the German occupation authorities and their Dutch, French and Belgian collaborators expelled Jews systematically and almost without exceptions: first from Amsterdam, then from Antwerp, and finally from Brussels and all other European cities.

In France, the German occupiers failed to achieve these first deportations there because of logistical issues and lack of local control. Most Jews from northern France could leave and escape to neutral countries. Several joined the French Resistance.

Arrested Jews in Belgium

The raids in Belgium

The German police mercilessly chased down and arrested Jews who were still living in Belgium, mostly in Antwerp and Brussels. But many had wisely left Belgium. About 75% of the remaining Jewish population was taken to concentration camps and death camps. Those that remained tried out their luck at hiding or mingled with the non-Jewish population to escape detection by the occupying forces, who had seen an over 50% reduction in the number of Jews living in Belgium after just two years there. The mostly Eastern European background of the Jews played a role in this: they had already fled anti-Semitism in their native country and knew both the methods and the horrific consequences of the persecution.

The French Vichy government and the persecution of Jews

The Dutch and Belgian governments had little to no influence over the occupier’s anti-Jewish policy in 1941. The Vichy government in France, though, played a significant role in the deportations. Thanks to them, the Germans could deport more Jews than they would have if they’d worked alone.

The French police arrested two out of three deported Jews and handed them over to the Germans. In Holland this was almost one in our and in Belgium almost one in six. The difference between Holland and Belgium can partly be explained by a larger share of arrested Jews in Holland who were then handed over to the Germans by members of their own country's police force.

From October 1942, the French government refused to continue to arrest Jews on a large scale and extradite them for deportation. This was mainly because of violent protest from churches and communities, especially in that part of France not occupied by Germany.

The American pressure behind the scenes also contributed to this decision by the French side from October 1942 onwards: firstly because Roosevelt made his disapproval clear at various points throughout 1943; secondly owing to simultaneous pressure exerted upon Spain; and thirdly because successive victories by Allied soldiers on land also brought closer capture (and hence occupation) by Nazi forces–meaning that living conditions would deteriorate

All this caused prolonged interruptions in the deportations in France. In short, the opportunistic role of the Vichy government initially aggravated the situation of the Jews in France, but because of the protests, changing circumstances and the growing resistance groups, fewer French than Dutch Jews would eventually be deported.

Jewish Resistance Fighters in France

Resistance, hiding and helping Jews

In Belgium and France, the organized resistance sprang up earlier than in Holland. The help to Jews citizens in need of hiding or escaping also began sooner. In October 1942, general and compulsory employment for Belgian and French men in German factories was introduced. This measure caused such a shock effect that many of them went into hiding or resisted.

Slumbering Jewish resistance and hiding coincided with this measure, so Jews joined in the organized resistance from the start of the deportations. However, the French and the Germans used snitchers, who’d receive monetary rewards for bringing in Jews.

In Holland, the violent suppression of the 1941 February strike deterred most Dutch resisters for over a year. Networks of hiding only emerged after the 1943 Spring strikes, when compulsory employment of dutchmen in Germany was increased. By then, most Dutch Jews had already been deported.

Numbers of victims

Of the over 30,000 Dutch Jews who went into hiding or attempted an escape abroad, about a third–sometimes after years of hiding–were betrayed or discovered and taken away, including the Frank family.

Holland had 102,000 Jewish victims and 107,000 deportees. Another 2000 Dutch Jews committed suicide or were killed or died in German captivity on Dutch territory: Camp Amersfoort, Camp Vught, Camp Westerbork, Ellecom, German prisons in the Netherlands.

These numbers also include Jews who died in hiding or who tried to escape to other countries and were caught or died in transit.

Victims of Razzia in Amsterdam May/June 1943

Number of people in hiding30,000 Jews were trying to escape the German claws by going into hiding. 2,000 of those tried to escape abroad. Of the 28,000 Jews hiding inside Holland, some 12,000 were arrested, which is more the 42%.

However, not all of these were betrayed by snitchers. Some 12,000 of those were deported because they had trespassed a so-called criminal law (not pertaining to curfew, not wearing the Star of David, or wearing it incorrectly, traveling without a valid travel permit, shopping outside Jewish shopping hours.)

The estimate is that about a third of the 30,000 Jews who first managed to first evade the deportations by going into hiding were eventually betrayed. Which is a sickening number. I don’t know what else to conclude.

Preorder The Crystal ButterflyBased (among others) on information by historians Pim Griffioen and Ron Zeller, authors of ‘Persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands, France and Belgium, 1940–1945: similarities, differences, causes’

March 19, 2023

Why did Holland have the highest number of Jewish victims during WW2? Part 2

Unveiling of “The Dokwerker” (The Docker) by Queen Juliana in 1952. The Amsterdam statue commemorates the general 1941 February Strike by the Dutch to protest against the suppression of their Jewish countrymen and women by the Germans.

In the first blog post of this series on the Jewish situation in Holland, Belgium and France after the German occupation in 1940, I explained the differences between the countries regarding their Jewish citizens and national governments. In this second part, we'll explore the tightening of the rules and regulations against Jews and the dire consequences thereof.

My next book in The Resistance Girl Series, The Crystal Butterfly, which comes out this summer, is a fictive but deeply-researched account of what happened to the Dutch Jews, their helpers and their traitors during WW2. This is the dedication I’ve chosen for the book:

Dedicated to all Dutch Jewish families who lost loved ones in World War 2 because of deportation and murder by the Nazis.

Dedicated to all descendants of Dutch citizens who stood up against the Nazis to protect their Jewish countrymen and women.

May the brave spirits of your beloved shine forever in my humble words.

Protest in the Netherlands against the mistreatment of Dutch Jews

In the second half of 1940, as the Nazis spread their sphere of power in Europe, they introduced a wide range of anti-Jewish legislation and cultural restrictions. The goal was to make Europe ‘Judenrein’, cleansed of Jews, although in the Netherlands this process was thwarted by some brave protests from non-Jews from all walks of life.

In Amsterdam on 11 February 1941, this Nazi policy ignited the strongest protest movement the occupation had seen so far. Jewish shops had been attacked on that day by the Dutch Nazis (NSB) who saw that as an opportunity to retaliate for a previous incident with German police officers. In retaliation, SS chief Rauter had some 400 Jewish men arrested and transported to a concentration camp in.

The arrests made on 11 February weren’t just random: Many non-Jewish Amsterdamers witnessed them and were shocked to see Jewish men being treated like cattle in their own city, where they had lived peacefully for centuries. A general strike erupted on 25 to 27 February, which at first only involved Amsterdam but soon took over the entire southern part of the country.

Even internationally such a staunch protest against the Nazi occupation had not been shown yet. The occupiers found themselves unexpectedly faced with a complete economic halt, paralyzed public transportation, and surrounded by masses of protesting Dutch people in what has become known as the February Strike.

This event marked the turning point in German and Dutch Fascist politics in which–at least for some time - open violence against Jews became unfashionable. From then on, the Nazi occupiers would employ more subtle but equally lethal methods to make Holland Judenrein.

The Jewish CouncilsIn France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, organizations were established with the sole aim of further excluding and extricating the Jewish populations.

In the Netherlands this was called “De Joodsche Raad van Amsterdam” (the Jewish Council of Amsterdam).

Hans Böhmker (left) who ordered the establishment of the Jewish Council in the Netherlands in 1941

The establishment of the Jewish Council for Amsterdam, was demanded on February 13, 1941 by Hans Böhmcker, Beauftragte of Amsterdam after the earlier mentioned riots in the Jewish quarter and the death of WA member Hendrik Koot.

Abraham Asscher and David Cohen formed the Jewish Council and became its chairmen. The main office was at Nieuwe Keizersgracht 58. The first call from the Jewish Council was to hand in weapons to the police station at Jonas Daniël Meijerplein.

In the second half of 1941, every major Dutch city had a Jewish council.

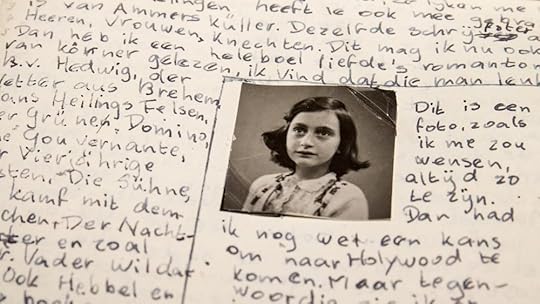

Anne Frank’s registration card for the Jewish Council

Part 3 of this series of blog posts follows soon.

In a separate blog post I will deal with the history of the Jewish Council, which was to become the most horrendous instrument the Nazis could impose on the Jewish citizens of Holland. It would give the occupiers all the data they needed for the raids and deportations. Unbeknownst to the Councils, they assisted in the eradication of their own people.

Preorder The Crystal ButterflyBased (among others) on information by historians Pim Griffioen and Ron Zeller, authors of ‘Persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands, France and Belgium, 1940–1945: similarities, differences, causes’

March 5, 2023

Why did Holland have the highest number of Jewish victims during WW2? (Part 1)

Jewish Quarter Amsterdam, 1941/1942

My new book, The Crystal Butterfly, is about a young woman who joins the Dutch Resistance movement in Holland during WW2. She helps Jewish families to hide in safe-houses and thus stay out of the claws of the Gestapo. Despite the heroic efforts of many Dutch citizens who helped their Jewish countrymen and women, Holland had the highest number of Jewish deportations and murders in concentration camps of all European countries. How could that happen?

75% of Dutch Jews were murdered in World War II. These percentages were much lower in nearby countries like Belgium and France. And one girl for the centuries to come will be engraved in our collective consciousness as the absolute meaninglessness of this extreme cruelty: the 15-year-old Amsterdam girl, Anne Frank.

On 4 August 1944, the Frank family was transferred to Westerbork transit camp in the Netherlands, then on the very last train to Auschwitz on 3 September. By that time, over 100,000 Jews had already been deported from the Netherlands, mostly to Auschwitz and Sobibor. Per capita, Holland had thus the most Jewish victims of the Nazi regime in all of Western Europe.

Part of Anne Frank’s Diary

The Jewish population before the warBefore 1940, the Netherlands, Belgium and France had a parliamentary democracy, which had been in place for decades. Anti-Semitism always existed but wasn’t practiced openly and legally, there were no differences between Jewish and non-Jewish citizens. Thel three countries had a low percentage of Jews: less than 5 percent.

The main difference between Holland and its southern neighbors was, though, that here 85% had lived in the country for centuries and was well-integrated before the war. In Belgium and France most Jews were immigrants from Eastern Europe or refugees after Hitler came to power in 1933. (Belgium: more than 90% percent, France about 50%).

German occupation of the Netherlands, Belgium and FranceOn May 10, 1940, Germany attacked the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. After the swift defeat, the countries were occupied. The Germans adopted the same policy in all three countries: cooperation with the sitting national governments, maintaining public order, and a gradual and increasing implementation of the Nazi ideology. Hitler reckoned that a smooth integration with the German economy would be most beneficial to his regime.

The relative freedom in these countries at the beginning of the war was contrary to what happened in the Nazi-occupied part of Poland. Here the Polish authorities were brutally crushed and the violence against the population and economic plunder took place from the beginning.

France and Nazi GermanyThe situation in France was different from that in Holland and Belgium in that not all of France was Nazi-occupied. After the defeat and the armistice of June 1940, the French government moved from Paris to Vichy in the so-called ‘free zone’, which lasted until November 1942.

Marshal Philippe Pétain, the new head of the French government, largely abolished democracy and the rule of law. The authoritarian regime collaborated with the Germans and assisted in persecuting the Jews also in the ‘free zone’.

As a result, the Germans did not need to enact anti-Jewish laws and measures in France. It was done by the French government itself.

Both Dutch and Belgian governments went into exile in London at the beginning of the war. The national administration was carried out by the highest officials, who stayed in the country and cooperated with the Germans for the interest of their peoples.

Why was the situation in Holland different from that in Belgium and France?

Make it stand out

In Holland, the Germans established a civilian occupation administration that had a strong influence of fanatical Nazis and the SS. The Germans considered the Dutch as a 'Germanic brother people', so they were supposed to adopt Nazism.

This was less the case in Belgium and certainly not in France. Belgium and the occupied part of France received a German military administration led by generals. They represented the interests of the army (the Wehrmacht) and focused their attention on the planned attack on the Great Britain.

Hitler appointed the Austrian Nazi and jurist Arthur Seyss-Inquart as head of the occupation administration in Holland. Seyss-Inquart was a fierce anti-Semite and so were his most important Dutch collaborators. They set the scene for the relentless Jewish persecution.

Arthur Seyss-Inquart

TO BE CONTINUED

Based on information by historians Pim Griffioen and Ron Zeller, authors of ‘Persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands, France and Belgium, 1940–1945: similarities, differences, causes’

Preorder The Crystal ButterflyFebruary 18, 2023

20 reasons to read WW2 novels

I tend to get remarks like these when I tell people I write WW2 novels:

Why are you still writing about WW2?

Aren’t there more interesting contemporary topics you can write about?

There are too many books about WW2 already. That topic its totally saturated.

Shouldn’t we move on from the war?

Who’s interested in those war stories today?

What a boring and depressing topic.

Though I totally get it that WW2 novels aren’t everybody’s cup of tea, I’ll give you 20 reasons how reading at least one book or novel about the biggest war in human history could broaden your horizons. Of course, as an author steeped in the WW2 history, I firmly believe we have to keep these (fictive) stories alive for posterity.

Here are my reasons and there might be some overlap.

1. To understand the causes and consequences of the conflict, which can help explain current events in the world. Why and how could WW2 happen? And could it happen again? What destructive forces should we be aware of and possibly neutralize before they grow out of hand?

2. To learn about the technological advances that shaped the conflict. The war catapulted us into the technological era we live in today.

3. To understand the roles of different countries and military powers during the war. And how that shaped the post-war global map.

4. To learn about the strategies and tactics used by the Allies and the Axis powers. What mistakes were made and/or victories claimed?

5. To gain a better understanding of the Holocaust and other war crimes committed during this time. The systematic murder of Jews and other minorities in Europe and the horrific situations in the Japanese camps are the worst and most large-scale crimes against own people within a short period of time. How could that happen and why did no one prevent it?

6. To gain an appreciation for the sacrifices made by those who served in the war. Military deaths from all causes totaled 21–25 million , including deaths in captivity of about 5 million prisoners of war. More than half of the total number of casualties are accounted for by the dead of the Republic of China and of the Soviet Union. Who knows that?

7. To appreciate the importance of international cooperation during this conflict. And how that led to the creating the United Nations after the war.

8. To better understand the role of propaganda during the war. Every side tells their own truth. As a WW2 author doing research, it is sometimes hard to get to the truth but it’s part of our job to unearth that. Misleading the population with pro-Nazi propaganda wasn’t just Joseph Goebbels’ job in Germany. The Allies also painted a rosy picture of their own achievements to keep up the morale.

9. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the history of the 20th century. It’s the recent history that shapes us who we are today. “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” – Maya Angelou

10. To gain insight into the lives of people, particularly the changing role of women, during WW2.

11. To gain a better understanding of the history and context of World War II. What was the build-up. Which forces collided and why? Could it have been prevented?

12. To gain insight into the human cost of the war, the impact on daily lives being forced into a fascist regime with few liberties, and ultimately hunger in many Western countries.

13. To learn about the major events of the war and understand their consequences. It should be general knowledge still to have a basic idea of the major battles, the countries where these took place and how they were recaptured and liberated by the Allies.

14. To gain an appreciation for the courage and sacrifice of the volunteers who fought in the war. Also again the women, in particular. Ordinary men and women sacrificed their jobs, families and homes to fight for freedom of their country.

15. To gain a better understanding of the culture and society of the time. The Jazz era had just begun but was forbidden by Hitler. Besides music, books were written and published and films were made. Under what consequence could culture still function?

The famous Casablanca film came out in 1942.

16. To gain insight into the different political ideologies that drove the war. The British appeasement politics, the failed neutrality in many countries, the aggressive National Socialism that was adopted by many outside Germany, Mussolini’s Fascism, the rise of Communism, the Japanese imperialism.

17. To learn about the different strategies and tactics employed by both sides. Maybe this is only for people interested in military tactics but the development of technology also led to,e.g. advanced spy craft on both sides.

18. To gain a better understanding of the technology and weapons used in the war. Again perhaps only for those interested in technology but all modern warfare took shape in WW2.

19. To gain a better understanding of how the war was reported and experienced by those who lived through it. The development of radio was new and helped people being informed even in occupied territory. Illegal newspapers and bulletins were printed

20. To gain a better understanding of the long-term effects of the war and its legacy. This one speaks for itself. Until deep into the 1970s and 1980s generations were scarred by the war and the effects can still be felt today.

February 12, 2023

Why The Nutcracker?

Clara is given an enchanted Nutcracker doll on Christmas Eve. As midnight strikes, she creeps downstairs to find a magical adventure awaiting her and her Nutcracker. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden Ballet 2016.

In the opening scene of my next book in The Resistance Girl Series, The Crystal Butterfly, we meet the Dutch ballerina Edda Van der Valk as she prepares herself to dance Clara in The Nutcracker in December 1938.

At the end of The Crystal Butterfly in 1946, we’ll return to a performance of Tchaikovsky’s famous ballet. But why The Nutcracker? Why not Swan Lake, or Gisele, or Romeo and Juliet? The Nutcracker’s theme is perfect for the dreamlike Edda Van der Valk. But let’s first look at the story of The Nutcracker.

In a nutshell: The Nutcracker is a two-act ballet based on E.T.A. Hoffmann's story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. It was first presented at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on December 18, 1892. The story takes place on Christmas Eve. The Stahlbaum family is celebrating the holiday with their daughter Marie (in the ballet she is called Clara), her brother Fritz, her godfather Drosselmeyer, and other family friends. Drosselmeyer surprises the party with a nutcracker doll, a gift for Clara.

That night, Clara has a dream in which the Nutcracker comes to life and battles with the Mouse King. The Nutcracker defeats the Mouse King with Clara’s help and turns into a handsome prince. He takes her on a magical journey to the Land of Sweets, where they meet the Sugar Plum Fairy and are entertained by various sweets from different nations. The Prince and Clara return home at the end of the night and Clara wakes up to find that the Nutcracker is back to being a toy. But she still fondly remembers the magical journey they took together.

The Nutcracker ballet is one of the most well-loved and popular ballets of all time because of Tchaikovsky’s beautiful music, the incredible choreography, and the magical story. The story of a little girl and her journey to the Land of Sweets, where she meets her beautiful Prince is the sublimation of a fairy tale. The Nutcracker also brings the Christmas season to life with its festive themes and has become a holiday tradition for many families. All happiness and festivity.

So much about the background of The Nutcracker story.

What is the ballet’s function in my WW2 novel about a young girl helping Jewish fugitives in Amsterdam during WW2?

Edda is a dreamer, a dancer, a girl who wants to shut her eyes to the world around her, her Nazi parents and the threat of war. She only wants to dance, and preferably with her boyfriend Asher Hoffmann. But real life is harsh and unyeilding: a battle of light and darkness, of the Nutcracker against the Mouse King, of good against evil, of art against reality. Edda roughly awakens from her dream life when her beloved Prince is taken from her by the Gestapo.

Will she herself even survive? Let alone hold on to her precious Christmas gift? A crystal butterfly made by Asher?

The Crystal Butterfly is inspired by Audrey Hepburn’s ‘dance through WW2’ in Holland.

The book is now on preorder and will release on 6 June.

Preorder NowJanuary 22, 2023

The Power of Resilience: Women in WW2

Miss Parker, a member of the Auxiliary Territorial Service, on duty as an enemy aircraft spotter near London, 1943.

Source: Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images.

The Second World War was a time of immense change and upheaval for women around the world. Women were called upon to take on roles that had previously been reserved for men, and they rose to the challenge with courage and determination.

Historical fiction about women in WW2 is a great way to explore the stories of these brave women and the struggles they faced. The war saw women taking on roles in the military, in factories, and in other areas of work that had previously been closed off. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that practical Women’s Lib was born in WW2 together with wearing overalls and breaking (societal) codes.

This blogpost is just a tribute in random pictures to the ordinary women forces in WW2, so not the fictional characters I describe in The Resistance Girl Series but individual resilient women from around the world whose contributions to the war and peace we should never forget.

Shawano Cleary | Special to the Kalamazoo Gazette

From the left, Dorothy Dodd Eppstein, Hellen Skjersaa Hansen, Doris Burmester Nathan and Elizabeth Chadwick Dressler, walk in front of a B-25 plane, as they were Air Force engineering test pilots for the B-25 during World War II.

Velma Briggs Moore, at right, with a coworker at Marinship in Sausalito, California.

RORI 3636

Group of Army Nurses. “The Army Nurse Corps.” WW2 US Medical Research Centre. Web. 27 Apr. 2015

During the Second World War many New Zealand women left their previous roles in the home and went out to paid employment. These women are working in the Colonial Ammunition Company in Hamilton in 1944, preparing bullets for the war effort.

Worker Women US Image Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

African American WAC employees distributing mail in Europe after D-Day.

Female dispatch riders and drivers in London during WW2

Female war correspondents

Women volunteering for farm work to produce vital food supplies.

Australian women working as welders.

Female codebreakers during WWII.

( Courtesy of National Security Agency )

January 8, 2023

2023: beginning of a new book

Since book 5 in The Resistance Girl Series, The Highland Raven, came out, I’ve taken a couple of months’ break from writing about WW2 to launch a new historical detective series The Mrs Imogene Lynch Series and to move to another part of Holland. Both were stressful events, but are now done and dusted.

When I set out to write the big books in The Resistance Girl Series in 2020, I took quite some time to plot the stories and get to the heart of my heroine’s journey before and during WW2. Next to doing all the research, that was a substantial job, and I pushed myself too hard to write too fast. These 125K volumes aren’t books you can just jot on the page and deliver to the world. So, I’m taking it a little slower this time. Most of January will be spent to to find out what makes Edda Van der Valk tick and to set up the book.

What I’m also going to do differently this time is share snippets of my story along the way, and do tons of on-the-spot research. As I’m now living close to Den Bosch and can easily travel to the most important places of action during WW2 in Holland, I’d like to share with you my explorations.

The Crystal Butterfly is also inspired by - though far from identical to - Audrey Hepburn’s Dutch war years, so I’ll take you to places where she lived and spent some of the most arduous years of her life.

Audrey Hepburn at the Arnhem Conservatory during the war

The Crystal Butterfly comes 6 June 2023.

Preorder nowDecember 4, 2022

2022 Christmas Scavenger Hunt Round-Robin: The Unsolved Case of the Secret Christmas Baby

Merry Christmas to you all! And welcome to the Christmas Christian Fiction Scavenger Hunt!

Merry Christmas to you all! And welcome to the Christmas Christian Fiction Scavenger Hunt!Here's how it works: At each participating author's blog, you will find a question that can be answered by checking out the free Amazon preview of their book or the preview offered via another link.

Note: You must answer the questions for every author in the round-robin to be considered to win the $250 first place, $150 second place or $100 third place Amazon gift cards. These prizes are USD values. If you are not a U.S. resident, you will get a gift card from the Amazon store for your country; however, it will be valued at these USD amounts.

At the end of my post is a link to the next blog in the hunt. And at the bottom of that blog, you'll find a link to the next blog, etc., to the very end, creating a circle (a round-robin) visit through all of the authors’ blogs.

I’m thrilled to get the chance to tell you about my new Christmas book The Unsolved Case of The Secret Christmas Baby. This is the first book in in the Victorian Mystery series: The Mrs Imogene Lynch Series. I'm very excited about this new series in a new historical genre for me. Hope you enjoy it too!

Writing a historical mystery was great fun as it is set in a different era from my usual "heavy" WW2 books. And I've always wanted to write a series with a female amateur sleuth in the lead. As I love everything Victorian, it was an absolute delight to create the opinionated but tender-hearted Mrs Imogene Lynch, a middle-aged, widowed constable wife, who never expected herself to be solving crimes on her own.

Let’s begin this scavenger hunt! Go to the book on Bookfunnel at this link. You will be taken to an excerpt of The Unsolved Case of the Secret Christmas Baby, the first book in this series.

Find the answer to this question:

Why is Mrs Imogene Lynch solving the case of the secret Christmas baby mystery?When you have the answer, FILL OUT THIS FORM and head on to the next blog!

Thank you so much for visiting! The next author on the tour is Katy Lee, who is telling us all about her Christmas book, Christmas K-9 Unit Horses. You can find her blog at this link. Remember that you must answer every question from all 20 authors in this collection and that the round-robin will end on December 11th at 11:59 PM EST.