Hannah Byron's Blog, page 18

September 24, 2020

World War 1 in a nutshell

I’m in no way a history buff but for my novel ‘In Picardy’s Fields’ I did some modest research into the background of this large-scale conflict and would like to share my findings with you. I only blog about things that I find interesting and getting some perspective on that elusive war helps me to see the bigger picture and that of the apocalyptic decades that followed after. I hope my clarifications are of some help to you.

Humanity and geopolitics have never been the same after the world was shaken up by the scale of its own capacity for destruction. Have we become more cautious? Do we realize how precious life really is? Have we learned from the wars? I’ll leave the answers to you. All I know is that the better we understand the bliss freedom from war is, the more we’ll appreciate it. Knowledge is power, after all.

Introduction

I don’t know about you but when I think back about the two world wars of the 20th century, I can kind of ‘get’ the Second World War: a dictator coming to power in the 1930s, repressing and stigmatising minorities and conquering the countries around him. Enough reason for the rest of the world to respond to and declare war on. But what about the first world war, the so-called Great War?

Do you know why it was fought? And why it escalated?

And what’s worse, do you think the millions of soldiers and civilians who senselessly died in the first world war knew why they were giving their lives and what for? I’m afraid the answer is NO. Most had probably never even heard of the minor royal Franz Ferdinand of Austria and the rigmarole that this Archduke was entangled in. Yet it was his assassination that triggered this worldwide bloodshed.

What did the European map look like before WW1?

Let’s have a look at the forces at work from roughly 1870-1914 that led to certain alliances and other countries being at loggerheads with each other.

Let there be no mistake. WW1 was a world war because it eventually spread out to all the oceans of the globe but in essence it remained a European conflict not unlike this Continent has known for centuries. Only this time it spread like wildfire. Historians see 3 causes for this:

The advance of military technology

The cultural differences of the nationalities.

The misconceptions of the various governments.

In 1914 the most powerful nation was undoubtedly the German Empire, created by the Kingdom of Prussia. It took up that powerful position after defeating the Austrian Empire and France in the second half of the 19th century. The conquered states reacted differently to their new position: the Austria-Hungary monarchy – with Austria aggressively suppressing its Hungarian counterpart – accepted the status of subordinate ally to Germany but France gritted its teeth in the wings.

On both sides of this tinderbox lay two superpowers not really eager to get involved in this Mid-European squabble: the semi-Asiatic Russian power with interest only in some south-eastern parts of Europe; and Great-Britain, that only wanted a stable Continent so it could expand and consolidate its world empire overseas. Spain, having lost most of its colonies to the United States was no longer a major player on the board but there was a new kid in town: Italy, unified under the House of Savoy, was very good at making itself an annoying nuisance.

In the course of the 19th century all these nations – some more successfully than others – had developed from agrarian societies ruled by the landed aristocracy and the Church to urbanized and industrialized states in which factory owners and increasingly the working classes came to power. This shift had destabilized century-old hierarchies and new balances were sought but had not yet been found.

A closer look at the chess-pieces on the board.

Britain

In this flight of the nations Britain took the lead, being not only the most ‘advanced’ power, but also the wealthiest and the first to lay a foundation for a welfare state. To ensure its 40-million inhabitants remained fed, the Royal Navy’s ‘command of the seas’ was vital and this egocentric need was the only real reason to keep a close eye on what was going on abroad, especially with these always bickering nations on the other side of the North Sea.

France

In France things did not go so well. The 1789 Revolution had destroyed the three pillars – monarchy, Church and noblesse – and left a deep rift in the French soul. The country lagged behind in economic development and could not come to terms with the demoralizing defeat against Germany in 1870, in which it lost Alsace and Lorraine. It was no longer the important player it had once been but it hung onto its powerful ally Russia.

Russia

For centuries and until today Russia has been a huge and powerful country but in the 19th century its strength was mostly feared by Britain. The Czars had expanded their empire to the south and the east, threatening Britain’s route to India via the Middle East and even the frontiers of India itself.

But Russia – powerful and vast as it was – was handicapped by its slow change with the times. Capitalism and industrialization came late to the 164 million population, most of whom had only emancipated from serfdom a generation earlier.

It was most likely Russia that was in the greatest turmoil of all the nations entering the 20th century. A heavily repressed nation, two important wars lost (Crimean war 1853-56 against the Alliance of France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia and the Japanese War 1904-5). The external fiascos were aggravated by two forces from within the nation that pulled in opposite directions. A rising voice that wanted liberation of the yoke of repression and cried for revolution and the ruling classes that did everything in their power to suppress that longing. Side note the term ‘terrorist’ was coined by suppressed Russian dissidents justifying the ‘extremes’ they were pushed to. There was a near revolution in 1905 but it took until 1917 for the Russian revolution to be a fact, leading to the abolishment of Czarism and the beginning of Bolshevism.

But what was Russia’s involvement in Europe? Asia was no longer a territory for expansion so it changed its focus to south-east Europe, which was still dominated by the Ottoman Empire. Orthodox-Christian groups in Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria turned to Russia for support, both as Christians and as fellow-Slavs. There were also a large number of Slavs (esp. Serbs and Croats), not living in independent countries but in Austria-Hungary, who – with their growing cry for independence – made the ruling Habsburg Monarchy restless. Russia did not shun from fanning those flames.

Austria-Hungary

In most West-European countries and in Russia nationalism was still a more or less cohesive force but Austria-Hungary consisted only of ‘submerged nations’ after it had become a Dual Monarchy in 1876. It’s most powerful submerged nation, the Magygars, where given a form of semi-independence in the Kingdom of Hungary (Budapest), sharing with the dominant German ‘Austrians’ the Emperor Franz-Joseph, the army and part of the government. The Magyars and the Germans considered themselves a superior race and suppressed their Slav minorities, the Slovaks, Rumanians and Croats. Under the moderately suppressive German ‘Austrian’ control, centred in Vienna, were the Czechs, Poles, Ruthenes, Slovenes, Serbs, and the people of South Tyrol. The Magyars ruling from Budapest were much less tolerant, which paralysed the dual government and forced the Emperor to govern by decree.

Germany

Imperial Germany, formed in 1871, was both the most complex and the most dynamic of all the nations. Though the economy was booming, it had socially hardly risen above feudalism. In the eastern part (Prussia) the Hollenzollern dynasty ruled by means of bureaucracy and the army. They resented the Reichstag (parliament), that in the unified empire represented the whole of Germany: the conservative agrarians in the east, the rich industrialists in the north and west, and the Roman Catholic Bavarians in the south, with the industrial working classes and socialism emerging in the valleys of the Rhine and the Ruhr area. The Reichstag was responsible for the finances but the government answered to the Kaiser. Between those two powers stood the Chancellor, the first and most famous one was the Prussian prince Otto von Bismarck, who had substantial influence on the Reichstag until 1890 but thereafter the Reichstag was merely a puppet instrument for the Kaiser Wilhelm II (reign 1888-1918).

Of course, we cannot blame one man for WW1 but what is certain is that Wilhelm II of the House of Hollenzollern had excessive power + a number of characteristics that were certainly volatile. He combined archaic militarism with opportunistic ambition and had a neurotically insecure disposition.

Militarism

Militarism had long been an inherent part of the Prussian culture but it had further increased in importance through the victories over France and Austria and the creation of the German Empire. This influence had led to a 3-year military service throughout Germany and the bourgeoisie now also allowed to wear the prestigious uniforms of the former military elite. The Kaiser always appeared in uniform as the All Highest War Lord, surrounded by his military entourage.

Ambition

The Germans prided themselves on being a superior and unique culture, with a wide range of music, science, philosophy, technology, scholars, topped with a booming industry that surpassed even Britain. They considered Russia despotic and the West decadent. But there was also inner turmoil brewing. The fast-growing industry made the cry for more democracy louder. By 1914 the Social Democrats were the largest party in the Reichstag.

Insecurity

Although not the best for friends – the landowners of the east and the industrialists from the west – their common threat was for sure socialism. To combat this, the ruling classes with at its head the Kaiser started promoting national greatness, de Weltmacht. A great army it already had, but what it lacked was a great fleet such as possessed by its largest ‘world competitor’ Britain.

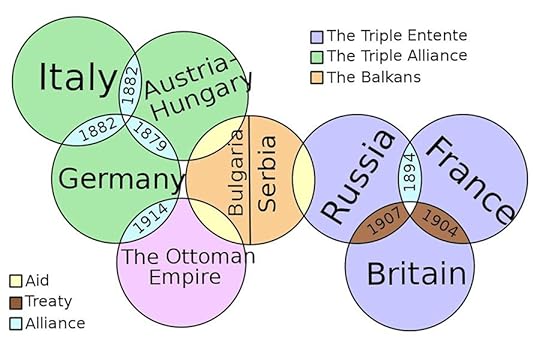

The Rival Alliances

The Triple Alliance

The Germany Empire felt itself surrounded by enemies although Bismarck had managed to forge collaboration with Austria-Hungary in the Dual Alliance. He also added Italy – that had territorial claims on France and the Mediterranean. This Alliance was known as the Triple Entente.

To keep the formidable Russia from entering an alliance with its ally France, Bismarck courted it in a Reinsurance Treaty. Britain favoured this treaty because its natural adversaries were France and Russia, so keeping those two apart suited the British best. Bismarck feared a war in the Balkans between Austria and Russia so he brokered an agreement that divided the Balkans into spheres of interests, where Russia kept an eye on the south and the Dual Monarchy on the north and the problematic Ottoman provinces, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Dual Alliance

But all this careful plotting fell apart by 1900 and Russia and France entered a military alliance in an attempt to rival the Triple Entente. Russia needed the investment capital France could offer to modernize its economy. This was the start of the armament race.

The Triple Treaty

The British were, of course, alarmed by all these alliances that popped up. It did not really see Germany as a big threat apart from that nation’s longing for a powerful fleet which led to a ‘naval war’. In need of allies it entered treaties with its former adversaries France (1904, Entente Cordiale) and Russia (1907) after the latter’s defeat by Japan. They settled disputes over Afghanistan and Persia. Britain also never lost sight of Its natural ally the US.

Meanwhile Germany was on a campaign to vilify Britain, which roused sentiments in both countries that these nations were natural enemies, which in fact they weren’t. But in the end, the outbreak of war was not between these two major powers. Bismarck had rightly foreseen that would happen on the Balkans.

The Balkan Crises

Not only the relations between Britain and Germany were quickly turning sour, the tensions between Austria-Hungary and Russia were also coming to a boiling point. The Austrians main fear was Serbia, because in their protectorate Bosnia-Herzegovina lived many Serbs that sought liberation from foreign rule, esp. in Bosnia. Austria even annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina to exercise more control. The Serb government responded by creating an open liberation movement for Bosnian Serbs with a covert terrorist wing called ‘the Black Hand.’ At the same time Russia encouraged Serbia to create a Balkan League together with Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro, to expulse the Turks from the peninsula. While the Turks were fighting Italy in Libya in 1912, this League – during the First Balkan War – saw the chance to expel the Turks. A second war to finish the job followed the next year.

After these two wars both the territory and the population of Serbia were doubled and it felt strong and ambitious. Frustration and fear reigned in Vienna at the seemingly unstoppable march of Serbia, which encouraged all Slav dissidents that were living in Austria and Hungary.

And then the whole thing blew apart: on 28 June 1914 the heir to the Habsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina, by Gavril Princip, a teenage terrorist trained and armed by the Serb-sponsored Black Hand.

Boom. Who had thought this was the match? Well it was.

This first post was become a rather long history lesson but I hope it has clarified some of the forces that pulled and tugged at each other from roughly 1870-1914. In the next post I’ll go into how this assassination led to the First World War.

July 25, 2020

The Thiepval Memorial

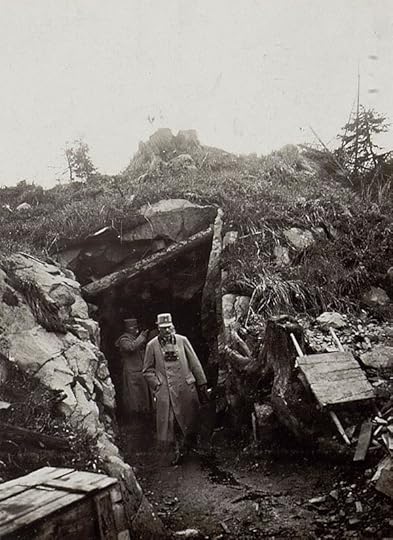

On a sunny August day in 2019, I set out from my house in the south of Holland to Picardy in northern France to commemorate my great-uncle Jack Westcott, whose name is engraved on the Thiepval Memorial as one of the ‘Missing of the Somme’. I planned a weekend trip to Amiens & surroundings to see first-hand the battlefields where my novel In Picardy’s Fields takes place. All photos are my own.

I visited many more places and memorials but for the sake of brevity I’ll concentrate on the Thiepval Memorial. I arrived there on the Friday afternoon and it was beautifully quiet; only a few people wandered around and the Museum/Visitor Centre was already closed, so I decided to return there the next day. The tall grass sang, the birds whistled, and the farmers harvested their crops.

Picardy’s fields, that slaughter place of the Great War, is immensely tranquil and free from strive these days. It has reclaimed its origin as farmland, rolling hills with yellow wheat, and sugar beets; meadows with cows, chewing lazily in the shadows of the trees. Through it all meanders the broad Somme River, glistening playfully in the sunlight and lined with rich green foliage. No guns, no mortars, no cries of agony or the boom-boom of cannons. Just the sounds of nature and an eerie silence rising from the more than one million souls lying deep in its soil. I don’t know if you’ve ever visited a battlefield spot, but I feel it in my whole being. I felt it too on the beaches of Normandy and I also felt it in Picardy. The extremes of hell and the peace thereafter. It’s eternal, it’s holy ground, one should trespass there with careful remembrance.

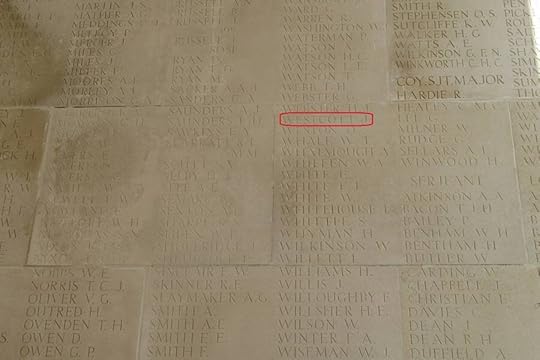

The Thiepval Memorial (for more info see Wikipedia) is a war memorial to 72,337 missing British and South African servicemen who died in the Battles of the Somme of the First World War between 1915 and 1918, with no known grave. The memorial was built around 1930 and is the largest Commonwealth Memorial to the Missing in the world. It is 140 feet (43 m) high and consists of 16 brick piers, having 64 stone-panelled sides. Only 48 of these are inscribed, as the panels around the outside of the memorial are blank. My Uncle Jack is on Pier and Face 11 C.

The next day I visited the Museum and found out that a British couple Pam and Ken Linge of Northumberland have been collecting photographs and biographical information relating to these ‘missing’ men since 2004 with the aim of recording and remembering their individual lives. The information is collected in the Visitor Centre’s database and the number of stories is growing every day. (http://www.greatwar.co.uk/organizations/thiepval-database-project.htm)

I am so incredibly proud that my Great-uncles Jack and William are now remembered in this databank thanks so my research (I’m the great-niece, Ferguson is my real name )

To round off this series of blogs on my family in WW1, some more photos from the Picardy battlefields. The Somme River; a German cemetery with the black crosses. We would almost forget that there were also 1,773,700 German casualties; and two more photos of Allied cemeteries.

The Thiepval Memorial

I visited many more places and memorials but for the sake of brevity I’ll concentrate on the Thiepval Memorial. I arrived there on the Friday afternoon and it was beautifully quiet; only a few people wandered around and the Museum/Visitor Centre was already closed, so I decided to return there the next day. The tall grass sang, the birds whistled, and the farmers harvested their crops.

Picardy’s fields, that slaughter place of the Great War, is immensely tranquil and free from strive these days. It has reclaimed its origin as farmland, rolling hills with yellow wheat, and sugar beets; meadows with cows, chewing lazily in the shadows of the trees. Through it all meanders the broad Somme River, glistening playfully in the sunlight and lined with rich green foliage. No guns, no mortars, no cries of agony or the boom-boom of cannons. Just the sounds of nature and an eerie silence rising from the more than one million souls lying deep in its soil. I don’t know if you’ve ever visited a battlefield spot, but I feel it in my whole being. I felt it too on the beaches of Normandy and I also felt it in Picardy. The extremes of hell and the peace thereafter. It’s eternal, it’s holy ground, one should trespass there with careful remembrance.

View from the Thiepval Memorial

The Thiepval Memorial (for more info see Wikipedia) is a war memorial to 72,337 missing British and South African servicemen who died in the Battles of the Somme of the First World War between 1915 and 1918, with no known grave. The memorial was built around 1930 and is the largest Commonwealth Memorial to the Missing in the world. It is 140 feet (43 m) high and consists of 16 brick piers, having 64 stone-panelled sides. Only 48 of these are inscribed, as the panels around the outside of the memorial are blank. My Uncle Jack is on Pier and Face 11 C.

The next day I visited the Museum and found out that a British couple Pam and Ken Linge of Northumberland have been collecting photographs and biographical information relating to these ‘missing’ men since 2004 with the aim of recording and remembering their individual lives. The information is collected in the Visitor Centre’s database and the number of stories is growing every day. (http://www.greatwar.co.uk/organizations/thiepval-database-project.htm)

I am so incredibly proud that my Great-uncles Jack and William are now remembered in this databank thanks so my research (I’m the great-niece, Ferguson is my real name

July 15, 2020

Uncle Jack’s Fight in France 1915-1916

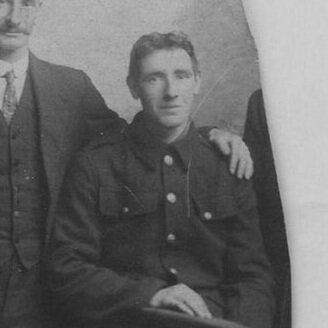

My great-uncle Jack was born in 1891 in Stone, Kent, GB to the Irish Mary Ann Meehan and the English George Richard Westcott. He was their 6th child and three years later my grandmother Gertrude Helen was born as the youngest of the lot. They later moved to Gravesend, where my grandparents used to live and where I spent many delightful summer holidays.

Before Jack enlisted on 13 January 1915, he was a grocery assistant. The ‘assistant’ makes it sound quite lowly but when I look at his face in the picture, I see a sweet, young man with a friendly countenance. He actually looks like many of the males in my family, more so than his 13-year-old brother William Alexander, who was Mary Ann and George’s eldest child.

Private Jack Westcott, January 1915

Jack went to France on 31st July 1915, so after a training of only 6.5 months! He was 23 at the time. His number was: Private, G/5489, 6th Battalion, Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment). For more information on Jack’s Regiment, which also fought bravely in WW2, see: Wikipedia

On 26th March 1916 Jack was appointed Lance Corporal, but he reverted to Private at his own request on 24th May 1916. He was killed at the very start of the Battle of the Somme on 3 July 1916 at the age of 24. His body was never found but he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial and the war memorial in Stone, Kent. More on Thiepval Memorial in my next blog post. This is all I have on Jack’s personal struggle.

Now, for the real history buffs amongst you, I’m now going to share some inside information about the Battle of the Somme, or the Somme Offensive that lasted from 1 July 1916 until 18 November 1916 (140 days). Jack died at the very beginning of it. Here’s the military map. This map’s been on my desk all the time I was writing In Picardy’s Fields, checking, and rechecking.

So, what happened at that fatal moment in Jack’s life? This is what the historians have pieced together.

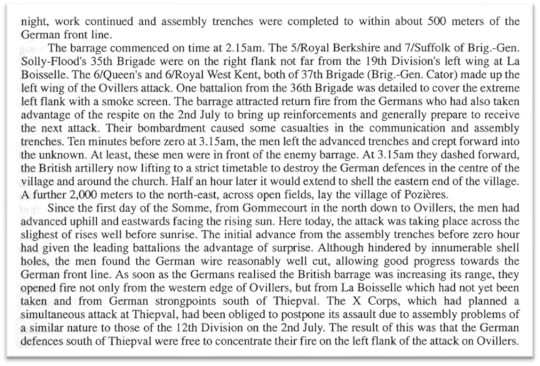

Extract from Ray Westlake’s book “British Battalions on the Somme.”

And an extract from Barry Cuttell’s book “148 Days on the Somme.”

Jack’s Battalion were part of the attack by 37th Brigade shown by the ’37 Brig’ arrow at the top

This has become an exceptionally long blogpost, but I hope it’s given you an idea of what happened to my great-uncle Jack Westcott in WW1. He WAS a hero! Now my own travels to the battlefields themselves in the next blog.

Uncle Jack’s Fight in France 1915-1916

My great-uncle Jack was born in 1891 in Stone, Kent, GB to the Irish Mary Ann Meehan and the English George Richard Westcott. He was their 6th child and three years later my grandmother Gertrude Helen was born as the youngest of the lot. They later moved to Gravesend, where my grandparents used to live and where I spent many delightful summer holidays.

Before Jack enlisted on 13 January 1915, he was a grocery assistant. The ‘assistant’ makes it sound quite lowly but when I look at his face in the picture, I see a sweet, young man with a friendly countenance. He actually looks like many of the males in my family, more so than his 13-year-old brother William Alexander, who was Mary Ann and George’s eldest child.

Subscript Private Jack Westcott, January 1915

Jack went to France on 31st July 1915, so after a training of only 6.5 months! He was 23 at the time. His number was: Private, G/5489, 6th Battalion, Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment). For more information on Jack’s Regiment, which also fought bravely in WW2, see: Wikipedia

On 26th March 1916 Jack was appointed Lance Corporal, but he reverted to Private at his own request on 24th May 1916. He was killed at the very start of the Battle of the Somme on 3 July 1916 at the age of 24. His body was never found but he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial and the war memorial in Stone, Kent. More on Thiepval Memorial in my next blog post. This is all I have on Jack’s personal struggle.

Now, for the real history buffs amongst you, I’m now going to share some inside information about the Battle of the Somme, or the Somme Offensive that lasted from 1 July 1916 until 18 November 1916 (140 days). Jack died at the very beginning of it. Here’s the military map. This map’s been on my desk all the time I was writing In Picardy’s Fields, checking, and rechecking.

Map of the 1916 Frontline in France

So, what happened at that fatal moment in Jack’s life? This is what the historians have pieced together.

Extract from Ray Westlake’s book “British Battalions on the Somme.”

And an extract from Barry Cuttell’s book “148 Days on the Somme.”

Jack’s Battalion were part of the attack by 37th Brigade shown by the ’37 Brig’ arrow at the top

This has become an exceptionally long blogpost, but I hope it’s given you an idea of what happened to my great-uncle Jack Westcott in WW1. He WAS a hero! Now my own travels to the battlefields themselves in the next blog.

July 10, 2020

My Great-uncles William and Jack Westcott

I’d like to take you on a tour of my personal connection with World War I. We will be visiting some archives and the Picardy region in northern France, where the various ‘Battles of the Somme’ took place between 1914-1918. It’s the subject matter of my novel In Picardy’s Fields, out in September 2020!

How it all started

My late mother, Helen Ferguson, was a keen amateur genealogist of both her own British/Irish ancestry and of the Dutch branch of my father’s family.

At first, I did not share my mum’s fascination with stuffy archives and bone-dry Internet sites, but I inherited the yellow envelopes with all her scribbles and earmarked photographs on her passing in 2017. Moving the envelopes one day – I had cautiously marked them ‘Hannah’s retirement project’- this photo fell out.

Standing left: William Alexander Westcott, sitting Jack Westcott (photo Jan 1915)

Now this was intriguing. First someone other than my mother had tried to identify the two relatives who had died in WW1 (see different handwriting in middle of backside note). Then my mother had done some more research and found out they were her uncles William Alexander Westcott and Jack Westcott, brothers to my maternal grandmother.

My great-uncles, my heroes

Faces of men who have died for our liberty, even if it was over a century ago, triggers something deeper than just another story about the Great War. And these weren’t just anyone’s faces; these were my blood relations, men who may or may not have done great deeds but in any case, died in an effort to deliver us from evil. And in doing so – dying young and childless – had both become as forgotten and untraceable as their bodies. Both were never found; anonymous men unless I change their fate. By making them my heroes, they become everybody’s heroes!

William and Jack’s WW1 war medals

It’s sad that my great-uncles never knew they were awarded these medals, let alone pin them proudly on their lapels. But I’ve cleaned and polished them to the best of my ability and ironed the ribbons. Side note: there is no one alive these days that can publicly wear these medals. The last WW1 veteran was Florence Green, a British citizen who served in the Allied armed forces, and who died 4 February 2012, aged 110. The last combat veteran was Claude Choules who served in the British Royal Navy (and later the Royal Australian Navy) and died 5 May 2011, aged 110.

Gosh, I keep being side-tracked; hope you forgive me.

July 1, 2020

Welcome

Welcome to my new blog & thank you for reading! I really hope you’ll enjoy finding out more about the background to my novels.

I love writing blogs but the most important reason for starting Historical Facts & Fiction is that there’s tons of research lying dormant in the recesses of my computer or in actual yellow envelopes that’s too precious not to share with the world. Most HF readers are fervent researchers themselves; half the fun of reading a good HF novel is popping onto the net to research the stuff you’ve just read. I know I can’t stop myself, and love to learn a thing or two in the process.

If this is you too, then welcome aboard.

Have you ever wondered where HF authors get their ideas for a new book or series, or how they do their research? No two HF authors are alike – of course – but we all do rely heavily on today’s search engines. No work gets done without it. However, as you’ll read in my next blog, my reason to start writing about WW1 was a family photo I found by chance. Curiosity is a good start.

It wasn’t only the photo that spurred me to write The Resistance Girl Series. It may sound terrible to say (and I won’t do so aloud) but I love the world wars. For me as a fiction writer they provide the greatest canvas on which to splash my stories, in an endless variety; this was the period – par excellence – in which ordinary people performed extraordinary deeds. And we all love us a decent hero(ine)!

I’m never tired of learning more about the first half of the 20th century and how it’s shaped our current society. So, let me infect you with some of that passion.

July 10, 2019

My Great-uncles William and Jack Westcott

I’d like to take you on a tour of my personal connection with World War I. We will be visiting some archives and the Picardy region in northern France, where the various ‘Battles of the Somme’ took place between 1914-1918. It’s the subject matter of my novel In Picardy’s Fields, out in September 2020!

How it all started

My late mother, Helen Ferguson, was a keen amateur genealogist of both her own British/Irish ancestry and of the Dutch branch of my father’s family.

At first, I did not share my mum’s fascination with stuffy archives and bone-dry Internet sites, but I inherited the yellow envelopes with all her scribbles and earmarked photographs on her passing in 2017. Moving the envelopes one day – I had cautiously marked them ‘Hannah’s retirement project’- this photo fell out.

My great-uncles, my heroes

Faces of men who have died for our liberty, even if it was over a century ago, triggers something deeper than just another story about the Great War. And these weren’t just anyone’s faces; these were my blood relations, men who may or may not have done great deeds but in any case, died in an effort to deliver us from evil. And in doing so – dying young and childless – had both become as forgotten and untraceable as their bodies. Both were never found; anonymous men unless I change their fate. By making them my heroes, they become everybody’s heroes!

It’s sad that my great-uncles never knew they were awarded these medals, let alone pin them proudly on their lapels. But I’ve cleaned and polished them to the best of my ability and ironed the ribbons. Side note: there is no one alive these days that can publicly wear these medals. The last WW1 veteran was Florence Green, a British citizen who served in the Allied armed forces, and who died 4 February 2012, aged 110. The last combat veteran was Claude Choules who served in the British Royal Navy (and later the Royal Australian Navy) and died 5 May 2011, aged 110.

Gosh, I keep being side-tracked; hope you forgive me.

My search for the truthAt first, I had no idea where to begin with my search for my great-uncles’ war history. The info my mother had left me was sparse and there were no family members to tell me more about this generation.

I soon found that the first step to find British war dead is to go to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (https://www.cwgc.org/), which is very helpful when you have first and last names. You wouldn’t believe how many names there are in that register! It baffles the grey cells. Within seconds both my great-uncles popped up. Well their names!

Register Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Sherlock Holmes’s amongst you will already have spotted the discrepancies. Either the War Graves Commission had their deaths wrong, or my mother. I can never ask her where she found these wrong dates but yes, hers were wrong, although only by a month. My great-uncles, unbeknown to each other, died within 8 days of each other, one aboard the S.S. Calypso, lying now on the bottom of the North Sea, 15 miles west of Listafjorden, Norway and the other near Ovillers, in hilly northern France. But we’re getting ahead of the search. Just for a moment imagine my poor great-grandmother, losing her eldest and her youngest son in a matter of days!

Private Jack WestcottFor the rest of this blog series I will concentrate my research on the youngest brother, Jack. I traced his path, and much more is known about him. We’ll start with the cap that rests on his knee. The emblem’s of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment). Stay tuned.