Hannah Byron's Blog, page 11

March 19, 2022

Blessed & Bestselling

My first 3 books in The Resistance Girl Series - In Picardy’s Fields, The Diamond Courier and The Parisian Spy - are consistent no #1 bestsellers in small categories. Now what does this mean?

The Amazon #1 bestselling flag

The Amazon #1 bestselling flag Nice and important as these orange tags are, they signal the books are selling well, but not that they are top in the overall charts. The categories that my books rank in are niche ones such as War and Peace, Women’s Studies History and 20th Century Literary Criticism. These are not necessarily categories I have chosen for my books. Amazon also assigns labels like these.

Things will only become really interesting when my books rank no 1 in categories such as Historical Fiction or World War 2 Fiction. This is not the case yet.

I’m what generally is called a mid-lister. My books rank between 6,000 and 25,000 in the Amazon shop, which is a blessed state. It means that of the millions and millions of books on offer, I leave most of them behind me. For now, this is a happy place. It means consistent sales and satisfied customers. Most of them, that is. ☺️😜

March 12, 2022

My Interview with Legendary Living Arts

A little while ago I did a podcast with Kellie Winzinowich, owner of Legendary Living Arts and Waking Way Productions. We had an in-depth discussion about my writing career and how and why I rebranded to Historical Fiction in 2020.

Above is the trailer for the podcast that can be found on YouTube.

Here are the links if you want to listen to the entire podcast. Enjoy!

March 5, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: The Liberation

The Fight in the North of Norway

With the beginning of the German withdrawal from Lapland in the winter of 1944-45, the initial German plan was to keep the essential nickel mines in the far North, but the losing war in other parts of Europe led the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht to order the entire army out of Finland to take up new defensive positions just north of Tromsø. This proved to be a huge logistical undertaking.

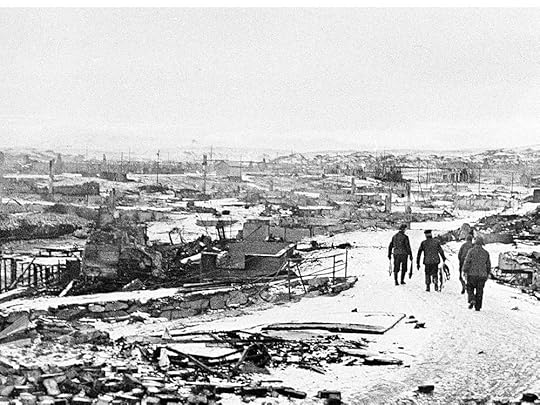

The beginning of the liberation in the north of Norway

In early October 1944, some 53,000 men of the German Army were still inside Russia. The plan was for them to arrive in Norway by 15 November. By 7 October, however, the combined Soviet Army and Northern fleet attack the weakest point of the German line.

A Soviet Naval Brigade also made an amphibious landing to the west, outflanking the Germans. With the Soviets hard on their heels, the Germans reached Kirkenes by 20 October. The German High Command ordered to hold the Soviets at bay while they could ship their vital supplies to safety. Five days later, the German army prepared to withdraw.

Scorched earth tactics in Finnmark

Because of their retreat, the Germans used the scorched earth policy. Kirkenes was virtually destroyed: the town was set on fire, port installations and offices were blown up and only a few small houses were left standing. This scene was repeated throughout Finnmark, an area larger than Denmark. The Germans were determined to leave nothing of value to the Soviets, as Hitler had ordered to leave the area devoid of people, shelter and supplies. Some 43,000 Norwegians followed the order to evacuate immediately; those who refused were forced to leave their homes after all. It is estimated that 23,000–25,000 inhabitants were still in East-Finnmark by the end of November, hiding in the wilderness until the Germans had left.

The Soviets pursued the Germans over the following days, however, their advance stopped, leaving West-Finnmark and North-Troms a no-man's-land between the Soviet and German armies.

On 25 October 1944, the order was given for a Norwegian force in Britain to set sail for Murmansk to join the Soviet forces now entering Northern Norway: "Operation Crofter".

At the beginning of 1945, the Norwegian forces slowly began taking back a battered Finnmark, helping the local population in the bitter arctic winter and dealing with occasional German raids from the air, sea and land and the ever-present danger from mines. Reinforcements arrived from the Norwegian Rikspoliti based in Sweden and convoys from Britain. On 26 April the Norwegian command sent out a message that Finnmark was free.

By March 1945, Norwegian Reichskommissar Josef Terboven had considered plans to make Norway the last bastion of the Third Reich and a last sanctum for German leaders. However, following Adolf Hitler's suicide on 30 April, Hitler's successor Admiral Karl Dönitz summoned Terboven and General Franz Böhme, Commander-in-Chief of German forces in Norway, to a meeting in Flensburg, where they were ordered to follow the General headquarters' instructions. On his return to Norway, General Böhme issued a secret directive to his commanders in which he ordered "unconditional military obedience" and "iron discipline"

German forces in Denmark surrendered on 5 May, and on the same day, General Eisenhower dispatched a telegram to resistance headquarters in Norway, which was passed on to General Böhme; it contained information on how to contact Allied General Headquarters.

Dönitz dismissed Terboven from his post as Reichskommissar on 7 May, transferring his powers to General Böhme. At 21:10 on the same day, the German High Command ordered Böhme to follow the capitulation plans, and he made a radio broadcast at 22:00 in which he declared that German forces in Norway would obey orders. This led to an immediate and full mobilisation of the Milorg underground resistance movement—over 40,000 armed Norwegians were summoned to occupy the Royal Palace, Oslo's main police station, as well as other public buildings. A planned Norwegian administration was set up overnight.

The following afternoon, on 8 May, an Allied military mission arrived in Oslo to deliver the conditions for capitulation to the Germans, and arranged the surrender, which took effect at midnight. The conditions included the German High Command agreeing to arrest and intern all German and Norwegian Nazi party members listed by the Allies, disarm and intern all SS troops, and send all German forces to designated areas. At this time, there were 400,000 German soldiers in Norway, which had a population of barely three million.

Following the surrender, detachments of regular Norwegian and Allied troops were sent to Norway, which included 13,000 Norwegians trained in Sweden and 30,000 Britons and Americans. Official representatives of the Norwegian civil authorities followed soon after these military forces, with Crown Prince Olav arriving in Oslo on a British cruiser on 14 May, with a 21-man delegation of Norwegian government officials and the rest of the Norwegian government and the London-based administration.

King Haakon VII returns to Norway

Finally, on 7 June, King Haakon VII and the remaining members of the royal family arrived in Oslo. General Sir Andrew Thorne, Commander-in-Chief of Allied forces in Norway, transferred power to King Haakon that same day.

Following the liberation, the Norwegian government-in-exile was replaced by a coalition led by Einar Gerhardsen which governed until the autumn of 1945 when the first postwar general election was held, returning Gerhardsen as prime minister, at the head of a Labour Party government.

Norwegian survivors emerged from the German concentration camps. By war's end, 92,000 Norwegians were located abroad, including 46,000 in Sweden. Besides German occupiers, 141,000 foreign nationals were in Norway, mostly now-liberated prisoners of war held by the Germans. These included 84,000 Russians.

10,262 Norwegians lost their lives in the conflict or while imprisoned. Approximately 50,000 Norwegians were arrested by the Germans during the occupation. Of these, 9,000 were consigned to prison camps outside Norway.

Aftermath

“Lebensborn” children

During the five-year occupation, several thousand Norwegian women had children fathered by German soldiers in the Lebensborn program. The mothers were ostracised and humiliated after the war both by Norwegian officialdom and the civilian population, and were called names such as tyskertøser (literally "whores/sluts of Germans"). Many of these women were detained at internment camps, and some were even deported to Germany. The debate on the past treatment of these krigsbarn (war children) started with a television series in 1981, but only recently have the offspring of these unions identified themselves and has an official apology about the trearment of these families been issued. A famous child of a Norwegian woman and a German soldier is ABBA member Anni-Frid Lyngstad, whose mother ad grandmother fled to Sweden to avoid the stigma.

Treason trials

Even before the war ended, there was a debate among Norwegians about the fate of traitors and collaborators. A few favored a "night of long knives" with extrajudicial killings of known offenders. However, cooler minds prevailed, and much effort was put into assuring due process trials of accused traitors. In the end, 37 people were executed by Norwegian authorities: 25 Norwegians on the grounds of treason, and 12 Germans on the grounds of crimes against humanity. 28,750 were arrested, though most were released for lack of evidence. In the end, 20,000 Norwegians and a smaller number of Germans were given prison sentences. 77 Norwegians and 18 Germans received life sentences. A number of people were sentenced to pay heavy fines.

The trials have been subject to criticism in later years. Some point out that sentences became more lenient with passaging time, and that many of the charges were based on the unconstitutional and illegal retroactive application of laws.

Legacy of the occupation

By the end of the war, German occupation had reduced Norway's GDP by 45% – more than any other occupied country. Besides this came the physical and patrimonial ravages of the war itself. In Finnmark, these were considerably important, as extensive areas were destroyed because of the scorched earth policy that the Germans had pursued during their retreat. Many towns and settlements were damaged or destroyed by bombing and fighting.

February 26, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: The Norwegian Labor Situation in WW2

At the beginning of the German invasion of Norway, Norwegian unemployment was already high, but after the capitulation on June 10, 1940, unemployment increased even further. For the duration of the war, both the Norwegian (read NS) and German authorities struggled to find enough workers to fulfill Hitler’s ambitions to fortify the country and map out his “Lebensraum” ideology.

The labor deficit worsened the longer the war lasted. No wonder both the Germans and Quisling's party used ever harsher methods to recruit unwilling (read resisting) workers.

To solve the problem of labour supply and management, Organisation Todt’s Einsatzgruppe Wiking became the commanding presence in the Norwegian labor market in 1942. The OT brought in German forces but also set out to force Norwegians to work for the Germans. Any voluntary aspect was gone.

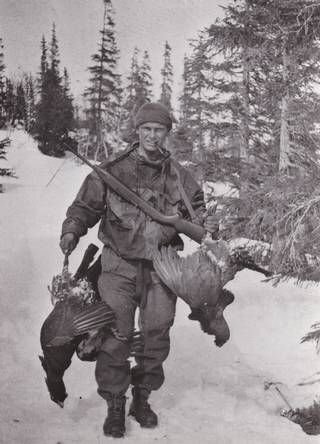

Surviving in the forests, trying to stay out of the Gestapo claws

The Resistance movement watched this process with growing suspicion. Knowing the shortage of workers (willingly or unwillingly), their central fear was the forced recruitment of young men not just filling labor spots in Norway, but also being sent to Germany. When Germany started to lose the war, a further fear rose that Norwegians would be used as Hitler’s cannon fodder.

The Labor Service Sabotage

In January 1944, the German situation had become so desperate, that the resistance movement considered it time for action. Plans had leaked that Norwegian youth (some 75,000) were going to be sent to the Eastern front to help the dwindling German army, forcing them into Waffen SS uniforms.

The now rather well-organized Home Front launched a large campaign against the Labor Service. Before the authorities could round up the youth, thousands of young men fled into the countryside and hid there. They became known as “the lads of the forest” and were kept alive with food and clothing by locals. There were already over 10,000 hidden lads near Oslo, and it was a huge logistical operation to keep them from being caught and imprisoned as they were now considered acting against the law. Furthermore, Norway was festered by agents provocateurs and informers, who operated mainly in rural areas.

The authorities claimed "the lads" had to be starved out and knowing the harsh winters, this was likely to happen. Ration cards were falsified to make sure the young men were fed, and locals did what they could.

More action was needed.

Quisling inspecting new workers

Successful Sabotage

The idea was to destroy the registration lists kept at the AT Headquarters in Oslo, but also in other parts of the country. The Home front decided to destroy the punch card machines that were used for creating the registration lists, and the lists themselves should be taken from the vaults and also destroyed. It was to be a cooperated mission carried out by Milorg but much went wrong in the sabotage's timing.

However, both the refusal of "the lads" to register and the spanner in the wheel of the authorities due to sabotage eventually proved triumphant for the resistance movement.

There was never a systematic and successful mobilization of Norwegian labor force during the war and the youth wasn't sent to fight at a German front. Again, the Norwegians had shown to stand tall and stand together.

February 19, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance, Eva Kløvstad-Jørgensen

Eva Antonie Kløvstad-Jørgensen

10 July 1921 – 8 June 2014

The resistance heroine who was not allowed to meet the King

Eva Kløvstad, née Jørgensen, from Hamar was the leader of 1200 resistance fighters. But when the liberation in Norway was celebrated, gender was an issue.

This is Eva's story...

The leader of District 25 in Milorg, Christian Juell Sandberg, went to the office in Strandgata 55 in Hamar as usual. The lawyer defied warnings that he could be exposed and that he should seek cover. When he opened the door, two armed Norwegian Gestapo officers were waiting for him. Sandberg reacted fast as lightning and threw himself out of the window. But he was shot in the back several times. He died of his wounds in hospital, a few days later.

Her boss' death was to change the life of 23-year-old Eva Jørgensen forever.

But being a resistance fighter had never been in Eva's thoughts since the Germans had invaded her country on the morning of April 9, 1940. She was still a high-school student at the time and a witness a few days later to how the Storting (Parliament) and the royal family fled from her city overseas to England. The war had come to Hamar. Already the first night, the Germans came in search of the royal family who were on the run.

Eva sat awake at night and heard gunfire on Stangebrua south of Hamar. Here the Nazi volunteers resisted. Among these was her fiancé Tor. Eva Jørgensen was desperate, but also angry and offended. But the 18-year-old did not think about organized resistance.

Joining Milorg

Four years later, in the autumn of 1944, much had changed. Fiancé Tor had fled and was in Sweden.

Eva Jørgensen worked as a stenographer and accountant at what was called the Transport Office in Hamar. Here, among other things, ration cards for petrol were organized and distributed to truck and taxi drivers.

Eva knew many of the drivers. She stole ration cards and gave them to drivers who transported refugees to Sweden. But she was still not involved in any organized resistance work.

But then one late autumn evening, Eva's phone rang.

Lawyer Christian Juell Sandberg wanted to meet her. She knew who he was. They shared an office in the same building. And he was the brother of a friend of hers. But what he was about to disclose to her in the dark in the driveway outside her house was a huge surprise.

He openly declared he was the leader of Milorg in Hamar and wanted her as his secretary, in particular for the upcoming traitor trial he expected would happen soon.

Milorg was founded on silence and that as few as possible should know as little as possible but Eva's position at the Transport Office with, among other things, petrol cards, had brought her into Milorg's light. It was a known fact that Eva worked systematically and soberly and thys was perfect for the job.

Though astonished Eva immediately said 'yes' astonishment, honored that she was asked but aware of the danger. All the horrors that had been happening to Norway in the four years of war, made her longing to contribute.

She and Sandberg met daily at the post office in Hamar. Both had errands here, so this was a place they attracted little attention. Eva did various errands for him, among them stenographing messages.

How she became the boss

She was without his leadership when Sandberg was shot. But coincidences did not end for Eva here. Before he died and, in his fever, Sandberg had shouted that Eva had to get to safety and go into cover. But the guards were German and didn't understand the dying man's words.

Eva was unsuspecting about all this but had already taken cover though she didn't know that she was in danger of being exposed. She had escaped.

A few weeks later, Eva was in despair. The entire Milorg district had collapsed after Sandberg's death. Since the summer of '44, the Germans and the Norwegian Nazis had rolled up much of the organization, after they'd found a list of participants in Oslo.

Some fled to Sweden, while others were arrested. Eve was not betrayed yet. But what should she do? It was not possible to contact the central management in Oslo. Then she had an 'aha' moment.

Sandberg had told her that he was going to meet a courier from Oslo at the hospital in Hamar the next day. There may lie her opportunity.

The courier went by the code name Blom. Neither he nor the central management knew about Sandberg's murder. Eva met Blom at the hospital, and after that the 23-year-old secretary became central in the reconstruction of the Hamar department of Milorg.

She was the only contact the Central Management in Oslo had. She received money, ration cards and eventually a radio. She had some local contacts she knew, and those in their turn had contacts they knew. She was in the process of arming a resistance cell.

Women at war

It is estimated that about 10 percent of the 50,000 Norwegians who were engaged in Milorg during the war were women. They participated in all kinds of resistance. Intelligence, courier and transport of refugees. They were also punished as severely as the men when they were arrested. Several ended up in concentration camps.

But very few got leadership positions. Even fewer got a position like Eva Kløvstad. Towards the end of the war, the 23-year-old from Hjellum outside Hamar was the actual leader of an organization of 1,200 resistance fighters.

Cover name Jakob

After the meeting with the courier a few weeks after Sandberg's murder, Eva started the patient and careful work of rebuilding District 25. After contact was established with Oslo, money, radio, ration cards and a revolver were hidden behind some planks in the wall.

Eva slowly but surely slipped into the role of leader. The organization she led believed there was a new man at the lead. There was no man, it was Eva with codename Jakob. One of those who received orders from Jacob without knowing who it was, was her boyfriend.

He would later react strongly to that.

Eva had a strong sense of justice. She was good at organizing, trusted, stubborn and not afraid to take responsibility. It was precisely such qualities that enabled her to take on the leader role.

She eventually appointed a weapon chief, a deputy commander and created a refugee route. She herself took responsibility for making sure exposed fighters could flee to Sweden.

Eva still worked at the Transport Office. She lived a double life. During the day, she was secretary Eva. In the evening and at night the resistance fighter Jakob. Her boss was lenient if she had to take time off, he too was involved in resistance work.

The organization grew to 1200 members from seven settlements. But when Eva received questions from close confidants about becoming a formal leader, she declined.

The central management in Milorg sent a man, Kolbjørn Henriksen, to lead the organization in Hamar. He started by building a new organization, while Eva kept the old one alive.

It became a kind of collective leadership. In practice, no one was formally appointed as leader but Eva was clearly the administrator and the de facto leader, says sources after the war.

Eva was always on guard. Worked day and night. She provided food and arranged weapons. Two transmitters from Sweden made sure there was contact with England every other day. The equipment came via air drop. The work was life threatening, and once Eva looked death in the eyes.

She was sitting in the office at Strandgata 53 in Hamar when she saw out of the window a German soldier who was mounting a machine gun. She was terrified and ran over to the other side of the office. There she also saw German soldiers on the street.

It was extra critical. She had just received a shipment of radios and messages from England that she had not yet read.

There was no time to burn them up.

But she was resourceful. A Norwegian Nazi in the next office had a wood stove. She tricked him out of the room by saying he had a phone call. Then she burned the material that could have been life-threatening for her.

At that moment the Germans weren't looking for her but hunting a deserter

The girlfriend

During the spring of 1945, the fight was wearing her down. All the time there was this fear of being revealed. Eva was constantly tense. But then her fiancé Tor returned from Sweden and that was happy moment, where they could spend a few hours together in a cabin. But it was not just a joy to see each other again. For Tor had no idea that when he received messages from Jakob, it was actually from Eva.

For Eva this was very hard. They were both friends and lovers. Thor was furious when he found out she was involved in illegal work. But Eva wouldn't listen, was both love and war at the same time.

Tor was not the only important fighter who returned. Several men who'd been central in the network came from Sweden that spring. The surprise was great when they returned to a well-functioning organization.

Eva after the liberation with other fighters

The liberation

In the spring of 1945, everyone was waiting for the inevitable. It was only a matter of days before the Germans would capitulate in Europe. Hitler had committed suicide on April 30 in his Berlin bunker.

But in Norway the Germans continued just as intensely as before to hunt down for resistance fighters.

On May 2, an ominous message came. The prison in Hamar was emptied. It was announced that something big was going to happen. Eva and the rest of the management in District 25 escaped to the forest, and hid in Furuberget outside Hamar.

In retrospect, it turned out that there was every reason for it. The man who had organized the meetings between Eva and the courier had cracked during interrogation and given her name.

Two Norwegian Gestapo leaders who were later sentenced to death came to arrest her at home. Without result. At the cabin in Furuberget, they organized guards and waited with bated breath. On May 4, the message came that Denmark was free. But what about Norway? The Germans still had hundreds of thousands of soldiers there.

On the 8th of May it was sunny and the leaves were sprouting on the birches. Eva was washing clothes in the basement when the message finally came. It was peace.

She ran out into the woods, fell to her knees, and thanked God as she wept. She gave in to the enormous pressure, always on duty and at work, had eroded.

Towards the end of the war Eva had insomnia as she feared the consequences if she was caught. For her family. For others in the group. Strangely brave, she wasn't afraid for herself.

Victory parties

On May 9, it was all over. Eva and the group went to Torggata in Hamar. She wore her khaki uniform, an anorak with a collar and an alpine hat. The gun was in her belt, leading her people. In the jubilation she heard her name and felt the surprise in the air. It's Eva! Few had guessed she was involved in the resistance. It made her feel proud and happy, but just a month later that would turn to bitterness.

On June 9, King Haakon was back in Oslo. The Karl Johan was packed with spectators. It erupted in cheers and celebration. Thousands of resistance fighters marched in front of the Palace. District 25 was also involved. But one fighter was missing. She who had led the resistance in the last months of the war. Eva Jørgensen.

She'd already received the warnings. When those who'd fled to Sweden returned in the spring of 1945. She felt sour eyes on her. She should have stepped down, leave the job to the men.

There was another blow. Milorg members were given an armband with markers that showed their rank. The formal leader of a group received six. Eva's fiancé had received five. She had to settle for three.

Bitterness & hope

The harsh message was Eva was not allowed to join the parade. It did not suit a woman. She had to stand and watch from Slottsplassen. Like all the other resistance women. What a showdown! But Eva had never been one to take the limelight, so she withdrew and let the other leaders of Hedmark shine.

What it led to for Eva was that for a long time after the war she didn't talk about her involvement. She repressed much of the horrible things that had happened. Only in her 80's, after 40 years, did she talk publicly about what she had been involved in.

This happened to many of these courageous women. Thus, the women's efforts for a long time remained the untold story of Norway's war.

It was simply not considered "female" to participate in military resistance work. Thus, women remained silent. Furthermore, it was men who wrote the story in the first years after the war. It was about the big lines and the big battles. It was about men. Some were also interested in writing books about their own efforts.

Eva Kløvstad was a hero. She was very brave. She eventually became vulnerable but still did a great job. Despite what happened in June 1945, she never regretted joining, and had many good memories.

The Milorg people held together after the war and had social gatherings. Then Eva Kløvstad was not neglected!

Eva would have turned 100 on July 10, 2021. She died on June 8, 2014.

NOTE HB: I only came to know of Eva’s story after The Norwegian Assassin was already written and edited. So it was very last minute that I wanted to add her amazing contribution to the war effort in Norway. This chapter is a ‘bad’ translation of a Norwegian newspaper article I found. Excuse Google Translate.

February 12, 2022

The Norwegian Assassin is LIVE!

My new book, number 4 in The Resistance Girl Series came out on Tuesday 8 Feb: The Norwegian Assassin. For 9 months I gave this story all I had, but it was still with some trepidation I added it to the immense pile of WW2 novels. I hoped for a warm reception as there aren’t that many books on Norway during the war.

So far - fingers crossed - all’s well with Esther’s story. The Norwegian Assassin constantly hovers between 5000 and 7000 in the Amazon store and that’s amazing news! There is an eagerness to read the book in Kindle Unlimited as well. After 4 days it has already had 55,000 page reads. 📖🎉

Okay, ‘nough bragging. Let’s take a look look at what the first reviewers are saying. ☺️ 😊

“It was amazing! An incredible story and a lot of historical research!” ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“Took my time reading this book because I did not want it to end, so fascinating and heartbreaking.”⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“This is a good story, it is fiction based on some true events in the fight for Norway. It is inspiring and often very sad in spots. I did enjoy reading the book and I think you will as well. I recommend this book.”⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“Despite the fraught and often sad narrative about what European Jews endured, this was quite an enjoyable and riveting narrative.” ⭐️⭐️⭐️

“What a great continuation to the "Resistance Girl" series, it's my favorite by far.”⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“These books are a unique take on the war and how women were involved, although fiction it’s very realistic.”⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“A really wonderful read! the characters are complex and interesting. The story kept me turning the pages and I could not put the book down.” ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“It's harrowing in parts (as one would expect given the storyline and the timeline) but in the end is a story where the heroine overcomes great personal loss and gives back to the Resistance in Norway.” ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“I think this book is well worth reading by readers who enjoy historical fiction. I recommend it for young adults through mature readers.” ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“I enjoyed being taken on Esther's story, and, despite the inevitable horrific scenes of a WWII-novel, learning something about the war in a country that doesn't often come up: Norway.” ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Intrigued by Esther’s story?

Get your copy of The Norwegian Assassin here.

Want to know more about Norway in WW2?

Subscribe to my newsletter and get this information booklet for free.

February 5, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: Up against Reichskommissar Josef Terboven

Reichskommissar Josef Terboven in Oslo, 1942

Josef Antonius Heinrich Terboven (23 May 1898–8 May 1945) was a Nazi leader, best known as the Reichskommissar for Norway during the German occupation of Norway.

Early life

Terboven was born in Essen, the son of minor landed gentry. He served in the German field artillery and growing air force in World War I and was awarded the Iron Cross, climbing to the rank of lieutenant. He read law and studied political sciences at the universities of Munich and Freiburg, where he first got involved in politics.

Nazi Party career

Dropping out of the university in 1923, Terboven joined the NSDAP with member number 25247 and took part in the unsuccessful Beer Hall Putsch in Munich. When the NSDAP was subsequently outlawed, he found work at a bank for a few years before he was laid off in 1925.

He next went to work full-time for the Nazi party. Terboven helped form the party in Essen and became Gauleiter there in 1928. From 1925 on, he was part of the Sturmabteilung, in which he reached the rank of Obergruppenführer by 1936. On 29 June 1934, Terboven married Ilse Stahl, Joseph Goebbels' former secretary and mistress. Adolf Hitler was the guest of honor at the wedding. Terboven was made Oberpräsident der Rheinprovinz in 1935 and developed a reputation as a petty and ruthless tyrant.

Rule of Norway

Terboven was made Reichskommissar for Norway on 24 April 1940, even before the military invasion was completed on 10 June 1940. He moved into the Norwegian crown prince's residence at Skaugum in September 1940 and made his headquarters in Stortinget (the Norwegian parliament buildings).

Terboven ruled Norway as a dictator. He did not have authority over the 400,000 regular German Army forces stationed in Norway, which were the command of General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, but he did command a personal force of around 6,000 men, of whom 800 were part of the secret police. Among his most brutal actions were his declaration of martial law in Trondheim in 1942, and ordering the destruction of Telavåg, and the deportation of Norwegian Jews. Terboven was hated by the Norwegians and not much esteemed, even by fellow Germans. Goebbels expressed annoyance in his diary about what he called Terboven's "bullying tactics" against the Norwegians, as they alienated the population against the Germans. Terboven nevertheless remained in ultimate charge of Norway until the end of the war in 1945, even after the proclamation of a Norwegian puppet regime under Vidkun Quisling, the Quisling government, in 1942.

As the tide of the war turned against Germany, Terboven's personal aspiration was to organise a "Fortress Norway" (Festung Norwegen) for the Nazi regime's last stand. He also planned concentration camps in Norway, establishing Falstad concentration camp near Levanger and Bredtvet concentration camp in Oslo in late 1941.

Death

With the announcement of Germany's surrender, Terboven committed suicide on 8 May 1945 by detonating 50 kg of dynamite in a bunker on the Skaugum compound. He died alongside the body of Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Rediess, SS and Police Leader and commander of all SS troops in Norway, who had shot himself earlier.

Terboven and Von Falkenhorst

In the war tribunals following WW2 Von Falkenhorst was interrogated at length how it was possible that Terboven could give orders to deport Jews and torture, deport and kill resistance fighters (both British and Norwegian), when he was the supreme German army commander of occupied Norway. It was a known fact that Von Falkenhorst had openly criticized Terboven and was replaced in 1944. Both men were ruthless war criminals and who exactly gave which command is unsure. Von Falkenhorst was sentenced to death, but escaped his fate and was released in 1953!

Oh my!

Terboven having fun while Norway bled

January 29, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: Up Against the Enigmatic Quisling

The quisling

On 24 October 1945, Vidkun Quisling, the Norwegian Nazi, was executed by a firing squad. He was the ultimate traitor, and a new word was introduced: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a ‘quisling’ is ‘a person cooperating with an occupying enemy force; a collaborator; a traitor.’

Before the war

Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and career had been promising. As a youth, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered quite a mathematical mastermind and he graduated from military school, with the highest marks ever recorded in Norway.

Quisling as prime minister

In his time in the army, he made it to the rank of Major. After he left in the 1920, Quisling became a humanitarian, during the great famines in Russia. In this period, he turned into a fervent anti-Communist and, was therefore, assisted the British in their diplomatic squabbles with the Soviets. This resulted in Quisling being awarded with the CBE in 1929, which King George VI revoked in 1940.

Between 1931 and 1933 Quisling was Norway’s Minister of Defence but then, disillusioned in the democratic system, he resigned and established his own Nasjonal Samling, ‘National Unity’ party, the Norwegian equivalent of the German Nazi Party. But the Norwegians had no sympathy for fascism and in the 1933 national elections, Quisling’s fascist party gained only a little over 2% of the votes and no seats in Parliament.

With no popularity and no substantive influence, Quisling’s political future in the Storting (Parliament) looked bleak. But when he visited Adolf Hitler in December 1939, he found his match.

His role during the War

Left to right: Quisling, Himmler, Terboven and Von Falkenhorst in Oslo 1941.

Six days before the Germans invaded Norway on 9 April 1940, Quisling met up with German agents in Copenhagen and shared intelligence about Norway’s defences. On the day of the invasion, Quisling went to the Oslo’s radio station to declare himself prime minister. German representatives demanded that Norway’s king, Haakon VII, accept Quisling’s position, but the king refused. He and his family were meanwhile in danger and had to flee to England, where the King headed the Norwegian government-in-exile.

But Quisling felt energized by the German backing and ordered all resistance activities to stop. However, once Germany had taken control of Norway, they did not make Quisling prime minister straightaway. Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar was his boss, but he played a prominent role in their government of occupation. Two years later, in 1942, Quisling was finally appointed prime minister, but the Germans still supervised him. However, his license to run the country in a fascist manner was increased.

Trial and execution

On 9 May 1945, the day after Germany’s unconditional surrender, Quisling was arrested. And King Haakon returned to his country.

Norway had abolished capital punishment in 1905, but the government-in-exile had reinstated it to order the death sentence for Quisling and two other Nasjonal Samling leaders, Albert Viljam Hagelin and Ragnar Skancke.

Charged with high treason, Quisling was executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945. He was 58.

Theories

Quisling rejected orthodox Christianity and called his own theory of life Universism. He had planned to make Universism the official state religion in Norway as “the positing of such a system depends on the progress of science.” He was a staunch believer in Norse mythology but further embraced the idea of reincarnation. Contrary to Hitler, whom he otherwise worshipped, Quisling was not overly charmed by race supremacy.

Quisling and Hitler in January 1945

In his book, also titled Universism, Quisling explained his views on morality, law, science, art, politics, history, race, and religion. He never finished it, and what was published of his work in newspaper articles has never been considered a great philosophical importance.

Personality

Quisling was a man of impulse. Not that his actions were based on sudden whims, but they did spring from hardcore convictions that spurred him to act in haste when he thought he saw an opening. He had many obsessions—for example; he wanted to believe that the Nordic race was the foundation of all civilization, but his knowledge of history thwarted his own beliefs, which he knew not to be true.

Another conviction was the romantic view of the position of the “sturdy peasant farmer” in society, which reminds us of Rousseau’s concept of ‘the noble savage’. He was a man torn by contradictory influences.

To his supporters, Quisling was considered a hard-working and conscientious administrator, knowledgeable and with an eye for detail. He propagated he cared about his people and maintained high moral standards. To his opponents, Quisling appeared unstable and undisciplined, abrupt, generally threatening. He was both these people, at ease with friends and stressed when confronted with his political opponents. During formal dinners, he repeatedly said nothing until abruptly bursting out in a flood of dramatic and sentimental rhetoric. He thought large groups to be conspiratorial.

As head of his government, Quisling rose early and worked hard. He actively took part in nearly all government matters, reading all letters addressed to him or his chancellery personally and marking a surprising number of action. Party members didn’t receive favors, nevertheless Quisling and his government didn’t himself share in the wartime hardships of fellow Norwegians. He never lived extravagantly.

Post-war interpretations of Quisling’s character are also mixed. Collaborationist behavior was largely viewed because of mental deficiency, leaving the personality of the clearly more intelligent Quisling an “enigma.” He was instead seen as weak, paranoid, intellectually sterile and power-hungry: ultimately “muddled rather than thoroughly corrupted.”

Another view is that Quisling was a mini-Hitler with a CMT (chosenness-myth-trauma) complex, or megalo-paranoia, more often diagnosed in modern times as narcissistic personality disorder. He was “well installed in his personality,” but unable to gain a following among his own people, as the Norwegian population wasn’t mirroring Quisling’s ideology. He was “a dictator and a clown on the wrong stage with the wrong script.” (biographer Dahl). One professor stated that quisling’s philosophical goals “fitted the classic description of the paranoid megalomaniac more exactly than any other case he’d ever encountered.” Thank God the Norwegians weren’t susceptible to the “Quisling mania” or things could have turned out different. (HB)

Mugshot Quisling 1945

Quisling never saw himself as a traitor. This is what he wrote in prison before his execution:

“I know that the Norwegian people have sentenced me to death, and that the easiest course for me would be to take my own life. But I want to let history reach its own verdict. Believe me, in ten years’ time I will have become another Saint Olav.”

Well, he hasn’t!

The Norwegian Resistance, X Up Against the Enigmatic Quisling

The quisling

On 24 October 1945, Vidkun Quisling, the Norwegian Nazi, was executed by a firing squad. He was the ultimate traitor, and a new word was introduced: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a ‘quisling’ is ‘a person cooperating with an occupying enemy force; a collaborator; a traitor.’

Before the war

Born 18 July 1887, Vidkun Quisling’s life and career had been promising. As a youth, the son of a Lutheran pastor, he was considered quite a mathematical mastermind and he graduated from military school, with the highest marks ever recorded in Norway.

Quisling as prime minister

In his time in the army, he made it to the rank of Major. After he left in the 1920, Quisling became a humanitarian, during the great famines in Russia. In this period, he turned into a fervent anti-Communist and, was therefore, assisted the British in their diplomatic squabbles with the Soviets. This resulted in Quisling being awarded with the CBE in 1929, which King George VI revoked in 1940.

Between 1931 and 1933 Quisling was Norway’s Minister of Defence but then, disillusioned in the democratic system, he resigned and established his own Nasjonal Samling, ‘National Unity’ party, the Norwegian equivalent of the German Nazi Party. But the Norwegians had no sympathy for fascism and in the 1933 national elections, Quisling’s fascist party gained only a little over 2% of the votes and no seats in Parliament.

With no popularity and no substantive influence, Quisling’s political future in the Storting (Parliament) looked bleak. But when he visited Adolf Hitler in December 1939, he found his match.

His role during the War

Left to right: Quisling, Himmler, Terboven and Von Falkenhorst in Oslo 1941.

Six days before the Germans invaded Norway on 9 April 1940, Quisling met up with German agents in Copenhagen and shared intelligence about Norway’s defences. On the day of the invasion, Quisling went to the Oslo’s radio station to declare himself prime minister. German representatives demanded that Norway’s king, Haakon VII, accept Quisling’s position, but the king refused. He and his family were meanwhile in danger and had to flee to England, where the King headed the Norwegian government-in-exile.

But Quisling felt energized by the German backing and ordered all resistance activities to stop. However, once Germany had taken control of Norway, they did not make Quisling prime minister straightaway. Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar was his boss, but he played a prominent role in their government of occupation. Two years later, in 1942, Quisling was finally appointed prime minister, but the Germans still supervised him. However, his license to run the country in a fascist manner was increased.

Trial and execution

On 9 May 1945, the day after Germany’s unconditional surrender, Quisling was arrested. And King Haakon returned to his country.

Norway had abolished capital punishment in 1905, but the government-in-exile had reinstated it to order the death sentence for Quisling and two other Nasjonal Samling leaders, Albert Viljam Hagelin and Ragnar Skancke.

Charged with high treason, Quisling was executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945. He was 58.

Theories

Quisling rejected orthodox Christianity and called his own theory of life Universism. He had planned to make Universism the official state religion in Norway as “the positing of such a system depends on the progress of science.” He was a staunch believer in Norse mythology but further embraced the idea of reincarnation. Contrary to Hitler, whom he otherwise worshipped, Quisling was not overly charmed by race supremacy.

Quisling and Hitler in January 1945

In his book, also titled Universism, Quisling explained his views on morality, law, science, art, politics, history, race, and religion. He never finished it, and what was published of his work in newspaper articles has never been considered a great philosophical importance.

Personality

Quisling was a man of impulse. Not that his actions were based on sudden whims, but they did spring from hardcore convictions that spurred him to act in haste when he thought he saw an opening. He had many obsessions—for example; he wanted to believe that the Nordic race was the foundation of all civilization, but his knowledge of history thwarted his own beliefs, which he knew not to be true.

Another conviction was the romantic view of the position of the “sturdy peasant farmer” in society, which reminds us of Rousseau’s concept of ‘the noble savage’. He was a man torn by contradictory influences.

To his supporters, Quisling was considered a hard-working and conscientious administrator, knowledgeable and with an eye for detail. He propagated he cared about his people and maintained high moral standards. To his opponents, Quisling appeared unstable and undisciplined, abrupt, generally threatening. He was both these people, at ease with friends and stressed when confronted with his political opponents. During formal dinners, he repeatedly said nothing until abruptly bursting out in a flood of dramatic and sentimental rhetoric. He thought large groups to be conspiratorial.

As head of his government, Quisling rose early and worked hard. He actively took part in nearly all government matters, reading all letters addressed to him or his chancellery personally and marking a surprising number of action. Party members didn’t receive favors, nevertheless Quisling and his government didn’t himself share in the wartime hardships of fellow Norwegians. He never lived extravagantly.

Post-war interpretations of Quisling’s character are also mixed. Collaborationist behavior was largely viewed because of mental deficiency, leaving the personality of the clearly more intelligent Quisling an “enigma.” He was instead seen as weak, paranoid, intellectually sterile and power-hungry: ultimately “muddled rather than thoroughly corrupted.”

Another view is that Quisling was a mini-Hitler with a CMT (chosenness-myth-trauma) complex, or megalo-paranoia, more often diagnosed in modern times as narcissistic personality disorder. He was “well installed in his personality,” but unable to gain a following among his own people, as the Norwegian population wasn’t mirroring Quisling’s ideology. He was “a dictator and a clown on the wrong stage with the wrong script.” (biographer Dahl). One professor stated that quisling’s philosophical goals “fitted the classic description of the paranoid megalomaniac more exactly than any other case he’d ever encountered.” Thank God the Norwegians weren’t susceptible to the “Quisling mania” or things could have turned out different. (HB)

Mugshot Quisling 1945

Quisling never saw himself as a traitor. This is what he wrote in prison before his execution:

“I know that the Norwegian people have sentenced me to death, and that the easiest course for me would be to take my own life. But I want to let history reach its own verdict. Believe me, in ten years’ time I will have become another Saint Olav.”

Well, he hasn’t!

January 22, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: Escape Routes

Overland Escape Routes

Overland Escape RoutesMuch of Norway lies within the Arctic Circle, so in winter the nights are interminable and temperatures often drop to minus 40C. The challenge escapers and evaders faced had often more to do with surviving the weather conditions than merely “getting away safely.” The long hours of nightly darkness could prove to be both an asset and a liability.

The principal escape routes were to the East, where Norway shared a long frontier with neutral Sweden. In the West, the escape opportunities came as the 1000-mile rugged coastline from the arctic to Southern Norway. As has been described in other chapters, from 1942, the Resistance movement was well organized and mainly based in Oslo. From there, organised escape lines were set out. It is estimated that some 50,000 - mostly—civilians escaped via Sweden.

In the 1940s, most Norwegians lived in cities and towns, but the coastline, with its many fishing villages, was also more populated than the hinterland. The small farming communities in inland Norway were mostly inhabitable during wintertime but the isolated farms in the mountains often had links to the Norwegian resistance movement that helped with creating escape routes.

There were many routes into Sweden, some of them in the far north, with extremely cold winter conditions. People trudged through the snow on foot or escaped on skis. Many downed airmen suffered from foot problems as their flying boots were unsuitable for mountain walking.

Escapees overland to Sweden passed through a network of isolated farmhouses or farming communes. Often the farmer or his family would escort the evaders on foot or skis to the next farmhouse in the chain. When farms were not available, evaders found shelter in mountain caves and woodcutters’ huts during the days and walked at night to keep warm; during the summer months, there were other problems because there was hardly any night and thus no hiding in the dark.

Apart from Commando raiding forces, several important land operations took place in Norway. The sabotage raids (see Chapter 5) took place together with the Norwegian Military (MilOrg) and SOE, the British Secret Service. All these men had to flee to Sweden as quickly as possible or take the sea escape route.

Overseas Escape Route

Overseas Escape Route The Shetland Bus

The sea escape was called the ‘Shetland Bus.’

The Shetland Bus (Norwegian Shetlandsbussene) was the code name secret resistance groups gave to an escape route they created between Shetland in Scotland and German-occupied Norway from 1941 until the end of the war. Secret agents, and Norwegians wanting or needing to flee occupied Norway, used it.

Before it became an official part of the Royal Norwegian Navy in October 1943, local fishers who made their small fishing boats and trawlers available for the Shetland Bus connection mainly ran it. A dangerous and daring form of resistance that wasn’t without major casualties. Later, three submarine chasers were added to the fleet, which enhanced the safety of the vessels.

They mostly made crossings during the winter when the nights were long, dark and there was no moon. A drawback was heavy conditions on the North Sea, sailing without lights and constantly risking being discovered by German planes or patrol boats.

Camouflage was considered the best defence, so they disguised the boats as ordinary fishing boats and the crew behaved like fishers. They were armed with light machine guns concealed inside oil drums on deck.

Formation

At the end of 1940, both the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and the Special Operations Executive (SOE) Norwegian Naval Independent Unit (not to be confused with another SOE Norwegian unit: the Norwegian Independent Company. No.1 or Kompani Linge), established a base in Lerwick in the Shetland Islands. Skippers from Norway who arrived there were asked to deliver agents to and from Shetland. In early 1941, it was formalized as help to SIS and SOE.

The main purposes were the transfer of agents in and out of Norway and the provision of weapons, radios, and other supplies. Transporting Norwegians who feared the arrest by the Gestapo were also part of the plan.

How it worked

Escapes were arranged with Mil Org with SOE in London. When evaders needed to get away, they contacted the Resistance, who informed SOE and then London was informed by radio.

SOE ran its own ‘delivery service’ of arms, ammunition and agents. The ‘Shetland Bus’ was the most northern of all escape line routes. A base was set up at Luna Voe on Shetland and the fishing boats, manned by volunteer fishers, who undertook the over 300 miles trips up to three times a week to the rugged fiords and inlets of the Norwegian coast, where many of the coastal villages supplied safe-houses for evaders and arms and ammunition dumps for the Resistance.

Famous Shetland Bus Members

The Shetland Bus crews were fishers and sailors with detailed local knowledge of both the Norwegian coastline and the North Sea between Norway and the Shetland Islands. Some sailed with their own vessels, others with boats given ‘on loan’. Most were young men in their twenties or thirties.

Leif Larsen (9 January 1906-12 October 1990)

Leif Larsen, nicknamed Shetland’s Larsen, was for sure the most famous of all the Shetland Bus men. He made 52 trips to Norway and became the most highly decorated Allied naval officer of the Second World War. Born in Bergen, Norway, he joined the Norwegian volunteers during the Finnish Winter War. Soon after, Germany invaded Norway, and Larsen fought in the Norwegian Campaign.

He arrived for the first time in Shetland with the M/B Motig I, in February 1941. After training with Kompani Linge in England and Scotland, Larsen returned to Lerwick in the St Magnus on 19 August 1941. He did his first Shetland Bus tour with M/B Siglaos, skippered by Petter Salen, on 14 September 1941. Many boats and many crew would follow. In October 1942, he had to scuttle his boat in Trondheimsfjord after a failed attempt to attack the German warship Tirpitz. He and the crew escaped to Sweden, but a British agent was arrested and killed.

On 23 March 1943, returning from Træna, Nordland, with M/K Bergholm, German aircraft attacked them. The boat sunk but Larsen and the crew, many of them wounded, rowed for several days until they reached the coast of Norway, near Ålesund, where in crew member died of his wounds. After hiding in different places, a Motor Torpedo Boat rescued them on 14 April. In October 1943, the new submarine chasers arrived and Larsen became commander of one of those, with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant. In total, he made 52 tours to and from Norway in fishing vessels and submarine chasers.

Kåre Iversen (10 October 1918 - 22 August 2001)

Kåre Emil Iversen was the son of a sea pilot and had joined his father on the pilot boat. When Norway was dragged into WW2, he was a fisher but soon joined the then forbidden Mil Org. When his activities were discovered, he fled to Shetland in August 1941 with his father’s boat, the Villa II. From Shetland, he went to England where he trained with the Kompani Linge.

He was with Larsen as crew member on M/B Arthur and did several trips with Larsen, but also with others. In December 1943, he became part of the crew on the submarine chaser Hessa until end of the war.

Iversen made 57 tours across the North Sea, most of them as engineer. In 1996 Iversen published his memoirs, I Was a Shetland Bus Man, which was reprinted in 2004 as Shetland Bus Man.

Shetland Bus Memorial

The Shetland Bus Memorial is at Scalloway, and the local museum has a permanent exhibition relating to the activities of the Shetland Bus. The memorial was built with stones taken from the village or places where each of the 44 crewmen who died on the Shetland Bus missions came from. The names of these men are shown on the four plaques arranged around the memorial.