Hannah Byron's Blog, page 12

January 22, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance, Escape Routes, IX

Overland Escape Routes

Overland Escape RoutesMuch of Norway lies within the Arctic Circle, so in winter the nights are interminable and temperatures often drop to minus 40C. The challenge escapers and evaders faced had often more to do with surviving the weather conditions than merely “getting away safely.” The long hours of nightly darkness could prove to be both an asset and a liability.

The principal escape routes were to the East, where Norway shared a long frontier with neutral Sweden. In the West, the escape opportunities came as the 1000-mile rugged coastline from the arctic to Southern Norway. As has been described in other chapters, from 1942, the Resistance movement was well organized and mainly based in Oslo. From there, organised escape lines were set out. It is estimated that some 50,000 - mostly—civilians escaped via Sweden.

In the 1940s, most Norwegians lived in cities and towns, but the coastline, with its many fishing villages, was also more populated than the hinterland. The small farming communities in inland Norway were mostly inhabitable during wintertime but the isolated farms in the mountains often had links to the Norwegian resistance movement that helped with creating escape routes.

There were many routes into Sweden, some of them in the far north, with extremely cold winter conditions. People trudged through the snow on foot or escaped on skis. Many downed airmen suffered from foot problems as their flying boots were unsuitable for mountain walking.

Escapees overland to Sweden passed through a network of isolated farmhouses or farming communes. Often the farmer or his family would escort the evaders on foot or skis to the next farmhouse in the chain. When farms were not available, evaders found shelter in mountain caves and woodcutters’ huts during the days and walked at night to keep warm; during the summer months, there were other problems because there was hardly any night and thus no hiding in the dark.

Apart from Commando raiding forces, several important land operations took place in Norway. The sabotage raids (see Chapter 5) took place together with the Norwegian Military (MilOrg) and SOE, the British Secret Service. All these men had to flee to Sweden as quickly as possible or take the sea escape route.

Overseas Escape Route

Overseas Escape Route The Shetland Bus

The sea escape was called the ‘Shetland Bus.’

The Shetland Bus (Norwegian Shetlandsbussene) was the code name secret resistance groups gave to an escape route they created between Shetland in Scotland and German-occupied Norway from 1941 until the end of the war. Secret agents, and Norwegians wanting or needing to flee occupied Norway, used it.

Before it became an official part of the Royal Norwegian Navy in October 1943, local fishers who made their small fishing boats and trawlers available for the Shetland Bus connection mainly ran it. A dangerous and daring form of resistance that wasn’t without major casualties. Later, three submarine chasers were added to the fleet, which enhanced the safety of the vessels.

They mostly made crossings during the winter when the nights were long, dark and there was no moon. A drawback was heavy conditions on the North Sea, sailing without lights and constantly risking being discovered by German planes or patrol boats.

Camouflage was considered the best defence, so they disguised the boats as ordinary fishing boats and the crew behaved like fishers. They were armed with light machine guns concealed inside oil drums on deck.

Formation

At the end of 1940, both the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and the Special Operations Executive (SOE) Norwegian Naval Independent Unit (not to be confused with another SOE Norwegian unit: the Norwegian Independent Company. No.1 or Kompani Linge), established a base in Lerwick in the Shetland Islands. Skippers from Norway who arrived there were asked to deliver agents to and from Shetland. In early 1941, it was formalized as help to SIS and SOE.

The main purposes were the transfer of agents in and out of Norway and the provision of weapons, radios, and other supplies. Transporting Norwegians who feared the arrest by the Gestapo were also part of the plan.

How it worked

Escapes were arranged with Mil Org with SOE in London. When evaders needed to get away, they contacted the Resistance, who informed SOE and then London was informed by radio.

SOE ran its own ‘delivery service’ of arms, ammunition and agents. The ‘Shetland Bus’ was the most northern of all escape line routes. A base was set up at Luna Voe on Shetland and the fishing boats, manned by volunteer fishers, who undertook the over 300 miles trips up to three times a week to the rugged fiords and inlets of the Norwegian coast, where many of the coastal villages supplied safe-houses for evaders and arms and ammunition dumps for the Resistance.

Famous Shetland Bus Members

The Shetland Bus crews were fishers and sailors with detailed local knowledge of both the Norwegian coastline and the North Sea between Norway and the Shetland Islands. Some sailed with their own vessels, others with boats given ‘on loan’. Most were young men in their twenties or thirties.

Leif Larsen (9 January 1906-12 October 1990)

Leif Larsen, nicknamed Shetland’s Larsen, was for sure the most famous of all the Shetland Bus men. He made 52 trips to Norway and became the most highly decorated Allied naval officer of the Second World War. Born in Bergen, Norway, he joined the Norwegian volunteers during the Finnish Winter War. Soon after, Germany invaded Norway, and Larsen fought in the Norwegian Campaign.

He arrived for the first time in Shetland with the M/B Motig I, in February 1941. After training with Kompani Linge in England and Scotland, Larsen returned to Lerwick in the St Magnus on 19 August 1941. He did his first Shetland Bus tour with M/B Siglaos, skippered by Petter Salen, on 14 September 1941. Many boats and many crew would follow. In October 1942, he had to scuttle his boat in Trondheimsfjord after a failed attempt to attack the German warship Tirpitz. He and the crew escaped to Sweden, but a British agent was arrested and killed.

On 23 March 1943, returning from Træna, Nordland, with M/K Bergholm, German aircraft attacked them. The boat sunk but Larsen and the crew, many of them wounded, rowed for several days until they reached the coast of Norway, near Ålesund, where in crew member died of his wounds. After hiding in different places, a Motor Torpedo Boat rescued them on 14 April. In October 1943, the new submarine chasers arrived and Larsen became commander of one of those, with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant. In total, he made 52 tours to and from Norway in fishing vessels and submarine chasers.

Kåre Iversen (10 October 1918 - 22 August 2001)

Kåre Emil Iversen was the son of a sea pilot and had joined his father on the pilot boat. When Norway was dragged into WW2, he was a fisher but soon joined the then forbidden Mil Org. When his activities were discovered, he fled to Shetland in August 1941 with his father’s boat, the Villa II. From Shetland, he went to England where he trained with the Kompani Linge.

He was with Larsen as crew member on M/B Arthur and did several trips with Larsen, but also with others. In December 1943, he became part of the crew on the submarine chaser Hessa until end of the war.

Iversen made 57 tours across the North Sea, most of them as engineer. In 1996 Iversen published his memoirs, I Was a Shetland Bus Man, which was reprinted in 2004 as Shetland Bus Man.

Shetland Bus Memorial

The Shetland Bus Memorial is at Scalloway, and the local museum has a permanent exhibition relating to the activities of the Shetland Bus. The memorial was built with stones taken from the village or places where each of the 44 crewmen who died on the Shetland Bus missions came from. The names of these men are shown on the four plaques arranged around the memorial.

January 15, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: The Inside Traitors

The heads of Hitler’s Puppet regimes in Norway and France

Introduction

Norway and France are comparable in the sense that both countries were operating as Nazi Puppet regimes during WW2. France had the Vichy Government headed by Philippe Petain in the southern part of the country until the Germans took control of all of France on 10 November 1942.

Norway had the Nasjonal Samling headed by Vidkun Quisling, but here the roles were reversed. In the first two years of the war, Quisling kept begging for the position of Prime Minister, but they only granted him this role under strict supervision of Reichskommissar Terboven on 1 February 1942.

I can’t prove my assumption, but based on what I’ve read on the occupied countries of Europe, both France and Norway had vast numbers of citizens actively betraying their fellow country(wo)men, who resisted the occupiers and their henchmen. This probably had much to do with the presence of a “legal fascist government.” These traitors were also instrumental in the deportation of their Jewish compatriots.

So, let’s have a look at the worst Norwegian traitor, Henry Rinnan.

Who was Henry Rinnan?

Henry Oliver Rinnan was born in Levanger (central Norway) on 14 May 1915, as the eldest of eight children. His family was poor. When fully grown, Rinnan was still only 1.61 metres (5 ft 3 in), which is exceptionally short for a Norwegian man. During his childhood, he was a lone wolf, who worked briefly for an uncle, but was fired for stealing.

During the Winter War (1939-1940), Rinnan attempted to enlist with the Finnish army to fight against the Soviets, but was rejected because of his poor physique. During the German invasion in April 1940, he drove a truck for the Norwegian Army. The Gestapo probably recruited him as early as June 1940. His parents were Nasjonal Samling members, but it is uncertain if Rinnan ever was.

‘Rinnanbanden’ or ‘Sonderabteilung Lola’

We know little about ‘Rinnan’s Gang’ in the early years of the war, but from September 1943, the ‘Rinnanbanden’ had its headquarters in Trondheim (coastal city in central Norway), known as Bandeklosteret (“gang monastery”). Rinnan worked closely with the German Sicherheitspolizei in Trondheim, where he had high-ranking contacts. It was also close to Rinnan’s family home.

The members of this independent Gestapo unit (Sonderabteilung Lola) masterfully infiltrated the resistance movement by mingling with Norwegians in buses, trains and cafes, and by inviting them to express their views on the Nazi occupation. When people expressed anti-German sentiments and were thus possibly members of the resistance movement, Rinnan and his agents continued to build a trust relationship with them and thus infiltrate the resistance networks.

The Rinnan gang is responsible for the death of at least 100 hundred Norwegian resistance fighters and British SOE agents. They tortured hundreds of captured resistance workers, brought in at least 1,000 arrests; gave the death blow to several 100 resistance groups. They even deceived resistance people into carrying out missions for the Nazis.

WW2 created many evil characters, and Rinnan was certainly one of them. He operated with impunity and little interference from the Gestapo, using murder and torture as sanctioned means. He was without doubt the meanest and most notorious Norwegian Gestapo agent in Trondheim and a wide area around it but it took the resistance movement a long time to find out who the big mole was.

The Germans were pleased with him, of course, and Rinnan was appointed SS-Untersturmführer der Reserve, and received the Iron Cross 2nd grade in 1944.

[image error]Rinnan’s Arrest

After Germany’s capitulation in May 1945, Rinnan and his band fled toward Sweden, but the number 1 Norwegian Gestapo agent, mass murderer, torturer and war criminal was caught in the Verdal Mountains, near the border to Sweden on 14 May 1945. He was in the company of, among others, his mistress and his brother,

One of those involved in his arrest, Alfred Olav Moe, knew that this was an important moment in history and took several photos of the incident.

Apparently, the hunt had been very strenuous, the terrain difficult, and it was still cold, even though it was well into May. To keep going without sleep or food, they took amphetamines to stay awake.

So, when Rinnan was arrested, it was with beating hearts and amphetamine intoxication. But the job was done.

On 24 December 1945, Rinnan escaped from prison, gathered some followers, but they were arrested again after a few days.

Rinnan’s Trial and Execution

During two trials in 1946, 41 Rinnan gang members were convicted and sentenced. 12 got sentences of execution by firing squad (10 of those were executed). The rest got long prison sentences. 40% of Norwegian war criminals that were executed were connected to Sonderabteilung Lola.

Rinnan was sentenced for personally murdering 13 resistance members, but the real number is much higher. He was executed on 1 February 1947 showing no emotion.

Per Sigurd Wiik

One of Rinnan’s gang members was Per Sigurd Wiik from Trondheim, who fought two enemies during World War II; Norwegian resistance fighters and his own boss, the torturer and intelligence officer Henry Oliver Rinnan.

After the war, Wiik was sentenced to death. The sentence was changed into life imprisonment. Thus, he managed to survive both Rinnan and the execution platoon.

According to Wiik, Henry Rinnan was a cynical rat and a vile but clever person. He was an ingenious intelligence officer and immediately saw if someone lied.

At Akershus Fortress, where the German seat of government was, the Rinnanbanden was regarded as a bunch of wild animals. The name “Lola” came from an erotic cover that Rinnan adored.

The German gave them training in the secret police provocation methods. It was about infiltrating and mapping resistance groups, winning their trust and then exploiting this against them.

Large parts of the resistance movement believed Rinnan was a royalist resistance leader. Only after the war did many learn how Rinnan had tricked them into believing that they were helping the Allies while, in fact, helping the Germans.

All this information was provided by Wiik and shows a horrible but truthful insight into the Rinnanbanden.

The Norwegian Resistance, The Inside Traitors, VIII

The heads of Hitler’s Puppet regimes in Norway and France

Introduction

Norway and France are comparable in the sense that both countries were operating as Nazi Puppet regimes during WW2. France had the Vichy Government headed by Philippe Petain in the southern part of the country until the Germans took control of all of France on 10 November 1942.

Norway had the Nasjonal Samling headed by Vidkun Quisling, but here the roles were reversed. In the first two years of the war, Quisling kept begging for the position of Prime Minister, but they only granted him this role under strict supervision of Reichskommissar Terboven on 1 February 1942.

I can’t prove my assumption, but based on what I’ve read on the occupied countries of Europe, both France and Norway had vast numbers of citizens actively betraying their fellow country(wo)men, who resisted the occupiers and their henchmen. This probably had much to do with the presence of a “legal fascist government.” These traitors were also instrumental in the deportation of their Jewish compatriots.

So, let’s have a look at the worst Norwegian traitor, Henry Rinnan.

Who was Henry Rinnan?

Henry Oliver Rinnan was born in Levanger (central Norway) on 14 May 1915, as the eldest of eight children. His family was poor. When fully grown, Rinnan was still only 1.61 metres (5 ft 3 in), which is exceptionally short for a Norwegian man. During his childhood, he was a lone wolf, who worked briefly for an uncle, but was fired for stealing.

During the Winter War (1939-1940), Rinnan attempted to enlist with the Finnish army to fight against the Soviets, but was rejected because of his poor physique. During the German invasion in April 1940, he drove a truck for the Norwegian Army. The Gestapo probably recruited him as early as June 1940. His parents were Nasjonal Samling members, but it is uncertain if Rinnan ever was.

‘Rinnanbanden’ or ‘Sonderabteilung Lola’

We know little about ‘Rinnan’s Gang’ in the early years of the war, but from September 1943, the ‘Rinnanbanden’ had its headquarters in Trondheim (coastal city in central Norway), known as Bandeklosteret (“gang monastery”). Rinnan worked closely with the German Sicherheitspolizei in Trondheim, where he had high-ranking contacts. It was also close to Rinnan’s family home.

The members of this independent Gestapo unit (Sonderabteilung Lola) masterfully infiltrated the resistance movement by mingling with Norwegians in buses, trains and cafes, and by inviting them to express their views on the Nazi occupation. When people expressed anti-German sentiments and were thus possibly members of the resistance movement, Rinnan and his agents continued to build a trust relationship with them and thus infiltrate the resistance networks.

The Rinnan gang is responsible for the death of at least 100 hundred Norwegian resistance fighters and British SOE agents. They tortured hundreds of captured resistance workers, brought in at least 1,000 arrests; gave the death blow to several 100 resistance groups. They even deceived resistance people into carrying out missions for the Nazis.

WW2 created many evil characters, and Rinnan was certainly one of them. He operated with impunity and little interference from the Gestapo, using murder and torture as sanctioned means. He was without doubt the meanest and most notorious Norwegian Gestapo agent in Trondheim and a wide area around it but it took the resistance movement a long time to find out who the big mole was.

The Germans were pleased with him, of course, and Rinnan was appointed SS-Untersturmführer der Reserve, and received the Iron Cross 2nd grade in 1944.

[image error]Rinnan’s Arrest

After Germany’s capitulation in May 1945, Rinnan and his band fled toward Sweden, but the number 1 Norwegian Gestapo agent, mass murderer, torturer and war criminal was caught in the Verdal Mountains, near the border to Sweden on 14 May 14 1945. He was in the company of, among others, his mistress and his brother,

One of those involved in his arrest, Alfred Olav Moe, knew that this was an important moment in history and took several photos of the incident.

Apparently, the hunt had been very strenuous, the terrain difficult, and it was still cold, even though it was well into May. To keep going without sleep or food, they took amphetamines to stay awake.

So, when Rinnan was arrested, it was with beating hearts and amphetamine intoxication. But the job was done.

On 24 December 1945, Rinnan escaped from prison, gathered some followers, but they were arrested again after a few days.

Rinnan’s Trial and Execution

During two trials in 1946, 41 Rinnan gang members were convicted and sentenced. 12 got sentences of execution by firing squad (10 of those were executed). The rest got long prison sentences. 40% of Norwegian war criminals that were executed were connected to Sonderabteilung Lola.

Rinnan was sentenced for personally murdering 13 resistance members, but the real number is much higher. He was executed on 1 February 1947 showing no emotion.

Per Sigurd Wiik

One of Rinnan’s gang members was Per Sigurd Wiik from Trondheim, who fought two enemies during World War II; Norwegian resistance fighters and his own boss, the torturer and intelligence officer Henry Oliver Rinnan.

After the war, Wiik was sentenced to death. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Thus, he managed the feat to survive both Rinnan and the execution platoon.

According to Wiik, Henry Rinnan was a cynical rat and a vile but clever person. He was an ingenious intelligence officer and immediately saw if someone lied.

At Akershus Fortress, where the German seat of government was, the Rinnanbanden was regarded as a bunch of wild animals. The name “Lola” came from an erotic cover that Rinnan adored.

The German gave them training in the secret police provocation methods. It was about infiltrating and mapping resistance groups, winning their trust and then exploiting this against them.

Large parts of the resistance movement believed Rinnan was a royalist resistance leader. Only after the war did many learn how Rinnan had tricked them into believing that they were helping the Allies while, in fact, helping the Germans.

January 8, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance: The Teachers’ Protest

Teachers on roll-call at a concentration camp near Oslo in 1942

Norwegian teachers prevent the Nazification of educationBackground

Within two months of invading Norway in April 1940, the Nazis had not only crushed military resistance and installed Quisling’s puppet regime, but the first signs of Nordic fighting spirit had already sprung up. The responses to Nazi takeover had been both nonviolently and violently. Mostly nonviolently. At first, it seemed legitimate to protest openly against the outward and inward aggression that was unleashed upon them, but as repression became harder and crueler, most of the resistance work had to go underground. Though this was not in line with the frank, fierce, and fearless Norwegians. But what could they do against a massive Wehrmacht and SS? In their country where there was 1 German to every 10 Norwegians?

By 1942, the main issue for the resistance movement had become maintaining Norway’s cultural and national identity if the occupation would go on for years. As has been pointed out earlier. One form of silent resistance had been wearing lapel pins and other symbols of Norwegian solidarity. In particular, the stay-together paperclip had gained popular acceptance. Another symbol was wearing flowers on 3 August to support their exiled King Haakon VII’s birthday.

While this began as a nonviolent protest, when soldiers started ripping off the pins, some Norwegians attached a sharp blade in the back of the pin to harm their attacker.

[image error]The Teachers React

The growing concern of teachers in the meddling of their educational methods by forcing their pupils to become “nazified”, ultimately led to the Teachers’ Defense of Education. We can only understand this immense and unified protest as an inherent part of this continual protest against fascism, which was the red thread in the resistance movement up till Norway’s liberation in 1945.

While many historians label the teacher’s resistance the pinnacle of Norwegian nonviolent resistance during World War II, it could only happen in this way in Norway and didn’t occur in a vacuum. Quisling and his Nazi supporters were busy establishing a Corporative State, in which the Nazification was inherent in every layer of society. When Quisling set out to corrupt the education system for this purpose, a unanimous response from the teachers was his answer. And with success, though at an exorbitant price.

The Great Uprise Against Educational Reforms

Quisling had founded the new Norwegian Teacher’s Union, which was to be implemented by the Norwegian storm troopers (Hird). All Norwegian teachers were required to be members of this new Union by February 5, 1942. After Quisling’s announcement, the ‘central’ resistance organization in Oslo sent out a directive for teachers to copy and send back to the authorities, stating their refusal to become a member, including their names and addresses. A bold sign of resistance, for sure. The directive easily reached the urban areas in the South of Norway, where teachers got it on time and took part en masse. Between 8,000 and 10,000 of the estimated 12,000 teachers eventually took part when it also became known in the more sparsely populated northern regions.

The massive teachers’ response send a wave of panic through the Quisling government. Schools were ordered to be closed for a month under the pretext that free school milk was unavailable. But it made the situation even worse. About 200,000 parents filed protest letters to the government for suddenly having their children without education. And the teachers continued to secretly teach their classes, defying government orders.

The Arrests

It wasn’t the first time Quisling was outmaneuvered by the Norwegian resistance, but it was certainly the most impressive protest so far. It ruffled the feathers of the real government under the leadership of Reichkommissar Terboven, who – without further ado - ordered the arrest of some 1,300 male teachers by mid-March. They were jailed and treated abominably.

But the resistance had its own answers. They continued to pay the salaries of the arrested teachers and those on strike, thus removing the most urgent financial pressure on their families.

The Gestapo pressurized the prisoners with ugly methods, but still the teachers–not military men, or fierce resistance fighters–nobly withstood the inhumane tactics. The Gestapo proved unable to break the teachers’ spirit.

There is a story of an almost retired teacher who was weak in health and had a large family. His fellow prisoners had told him they were okay with him signing the membership of Quisling’s Union to be free and go home. They would not hold it against him. He said he would, but then he came out of the interrogation room, raised his fist and cried out: “I will not bow to slavery. I will not pollute the minds and spirits of Norway’s youth. I’ll never sign.”

In April 1942, the government sent some 500 imprisoned teachers to a concentration camp near Kirkenes, in the arctic. Here they were set to work alongside Russian prisoners of war.

When news of this action became known, students and farmers gathered along the tracks to sing and offer food as the train passed. The teachers also formed their own choirs and gave lectures in order to maintain their sanity and pass the time.

In May, the Church and Education Department seem to give up the idea of a successful fascist teachers’ organization. All the teachers asked to go back to work, but it would take another six months for Quisling to beat the retreat. The teachers didn’t budge, but many died from hard labor, undernourishment, or cold.

Quisling’s Defeat

Eventually, even Quisling understood he was losing whatever legitimacy he still had in the eyes of the population. By November 4, 1942, all the teachers were liberated from the concentration camp and went back to work.

Norwegian pride against fascist infiltration of the school curriculum solidified the resistance movement. It was their first big success, which had started with that simple directive to refuse membership in the New Teachers’ Union. The Norwegian people had spoken. From now on, they took even more pride in giving Quisling so much resistance that he was ultimately forced to give up his idea of the Corporative State altogether. Norwegian culture had prevailed.

The Norwegian Resistance, The Teachers’ Protest, VII

Teachers on roll-call at a concentration camp near Oslo in 1942

Norwegian teachers prevent the Nazification of educationBackground

Within two months of invading Norway in April 1940, the Nazis had not only crushed military resistance and installed Quisling’s puppet regime, but the first signs of Nordic fighting spirit had already sprung up. The responses to Nazi takeover had been both nonviolently and violently. Mostly nonviolently. At first, it seemed legitimate to protest openly against the outward and inward aggression that was unleashed upon them, but as repression became harder and crueler, most of the resistance work had to go underground. Though this was not in line with the frank, fierce, and fearless Norwegians. But what could they do against a massive Wehrmacht and SS? In their country where there was 1 German to every 10 Norwegians?

By 1942, the main issue for the resistance movement had become maintaining Norway’s cultural and national identity if the occupation would go on for years. As has been pointed out earlier. One form of silent resistance had been wearing lapel pins and other symbols of Norwegian solidarity. In particular, the stay-together paperclip had gained popular acceptance. Another symbol was wearing flowers on 3 August to support their exiled King Haakon VII’s birthday.

While this began as a nonviolent protest, when soldiers started ripping off the pins, some Norwegians attached a sharp blade in the back of the pin to harm their attacker.

[image error]The Teachers React

The growing concern of teachers in the meddling of their educational methods by forcing their pupils to become “nazified”, ultimately led to the Teachers’ Defense of Education. We can only understand this immense and unified protest as an inherent part of this continual protest against fascism, which was the red thread in the resistance movement up till Norway’s liberation in 1945.

While many historians label the teacher’s resistance the pinnacle of Norwegian nonviolent resistance during World War II, it could only happen in this way in Norway and didn’t occur in a vacuum. Quisling and his Nazi supporters were busy establishing a Corporative State, in which the Nazification was inherent in every layer of society. When Quisling set out to corrupt the education system for this purpose, a unanimous response from the teachers was his answer. And with success, though at an exorbitant price.

The Great Uprise Against Educational Reforms

Quisling had founded the new Norwegian Teacher’s Union, which was to be implemented by the Norwegian storm troopers (Hird). All Norwegian teachers were required to be members of this new Union by February 5, 1942. After Quisling’s announcement, the ‘central’ resistance organization in Oslo sent out a directive for teachers to copy and send back to the authorities, stating their refusal to become a member, including their names and addresses. A bold sign of resistance, for sure. The directive easily reached the urban areas in the South of Norway, where teachers got it on time and took part en masse. Between 8,000 and 10,000 of the estimated 12,000 teachers eventually took part when it also became known in the more sparsely populated northern regions.

The massive teachers’ response send a wave of panic through the Quisling government. Schools were ordered to be closed for a month under the pretext that free school milk was unavailable. But it made the situation even worse. About 200,000 parents filed protest letters to the government for suddenly having their children without education. And the teachers continued to secretly teach their classes, defying government orders.

The Arrests

It wasn’t the first time Quisling was outmaneuvered by the Norwegian resistance, but it was certainly the most impressive protest so far. It ruffled the feathers of the real government under the leadership of Reichkommissar Terboven, who – without further ado - ordered the arrest of some 1,300 male teachers by mid-March. They were jailed and treated abominably.

But the resistance had its own answers. They continued to pay the salaries of the arrested teachers and those on strike, thus removing the most urgent financial pressure on their families.

The Gestapo pressurized the prisoners with ugly methods, but still the teachers–not military men, or fierce resistance fighters–nobly withstood the inhumane tactics. The Gestapo proved unable to break the teachers’ spirit.

There is a story of an almost retired teacher who was weak in health and had a large family. His fellow prisoners had told him they were okay with him signing the membership of Quisling’s Union to be free and go home. They would not hold it against him. He said he would, but then he came out of the interrogation room, raised his fist and cried out: “I will not bow to slavery. I will not pollute the minds and spirits of Norway’s youth. I’ll never sign.”

In April 1942, the government sent some 500 imprisoned teachers to a concentration camp near Kirkenes, in the arctic. Here they were set to work alongside Russian prisoners of war.

When news of this action became known, students and farmers gathered along the tracks to sing and offer food as the train passed. The teachers also formed their own choirs and gave lectures in order to maintain their sanity and pass the time.

In May, the Church and Education Department seem to give up the idea of a successful fascist teachers’ organization. All the teachers asked to go back to work, but it would take another six months for Quisling to beat the retreat. The teachers didn’t budge, but many died from hard labor, undernourishment, or cold.

Quisling’s Defeat

Eventually, even Quisling understood he was losing whatever legitimacy he still had in the eyes of the population. By November 4, 1942, all the teachers were liberated from the concentration camp and went back to work.

Norwegian pride against fascist infiltration of the school curriculum solidified the resistance movement. It was their first big success, which had started with that simple directive to refuse membership in the New Teachers’ Union. The Norwegian people had spoken. From now on, they took even more pride in giving Quisling so much resistance that he was ultimately forced to give up his idea of the Corporative State altogether. Norwegian culture had prevailed.

January 2, 2022

The Norwegian Resistance Movement in WW2, The Paperclip VI

Symbol of Norwegian Unity and Resistance

The paperclip was a patriotic symbol of resistance in Norway during the Second World War.

Paperclips on lapelsAs early as the fall of 1940, students at Oslo University began wearing paperclips on cuffs and lapels. It started as a grassroots campaign, but quickly became a widespread, silent and non-violent protest against the Nazi occupation of Norway. This small, almost invisible symbol was also an expression of unity and national pride, only understood by Norwegians.

On 25 September 1940 Reichskommissar Terboven had declared the King and the Government-in-Exile deposed, and outlawed all political parties other than the Nasjonal Samling (Quisling’s National Socialist party). All activities to support the Royal Family were forbidden. Though King Haakon VII stood firm in his resolve to fight until Norway was liberated, wearing symbols connected to the Royal family had become too obvious.

The paperclip also stood for the rejection of the ideology, with which the Nazis tried to infiltrate Norwegian culture and heritage. Next to sticking a single paperclip on a lapel, people also wore paperclip bracelets. The bracelets were a further symbol of Norwegians’ unity in face of adversity.

Vaaler the Paperclip inventor

Why the paperclip?The paperclip as a resistance symbol is brilliant in its simplicity. The occupying power would certainly (at first) overlook it as an item of unimportance.

But there were other reasons apart from its insignificance.

Paperclips are used to bind things (paper), they are cheap, readily available and its inventor was a Norwegian by the name of Johan Vaaler. There is some dispute about the invention of this type of paperclip by Vaaler, but let’s not squabble over this. It worked for the Norwegians as the idea of their invention and a perfect tool as a subtle, non-violent form of resistance to carry every day.

“Vi holder sammen” = we are bound together

Paperclip statue

VerbotenAt some point, the Germans understood the paperclip protest, and they forbade the wearing of the protest clip, labeling them a criminal violation. Still, Norwegians continued to show their patriotism and irritate their oppressors with their ‘innocent paperclip’.

Paperclip bench

After the WarThe paperclip continues to be a symbol of pride for Norwegians connected to WW2 and, in many places, large paperclips were erected as statues. On 29 May, which is National Paperclip Day, Norway celebrates this day in particular.

My personal contribution

I love this form of protest. I think it’s brilliant and I don’t think I’ll ever be able to think of the simple paperclip as just a handy forged piece of metal.

December 29, 2021

More than 600 FREE Books!

Only available on 30 December!!

I feel like a belated Santa Claus. At the end of 2021 I may give away 600+ Romance books in all genres! There will be something for everyone! And no strings attached! Just a great selection of free books.

The Romance Bookworms offer is only valid on 30 December. The rest of the promos below are a a bit longer.

Here’s the link to the Romance Bookworms site .

The Diamond Courier, the 2nd book in The Resistance Girl Series takes part in the Romance Booksworms promo but is also free on 31 December. Get it here.

2. Win a bundle of 30 Books that Inspire. Thru to 5 Jan.

Then there is the Giveaway with a chance to win an Ereader. Among those great books is In Picardy’s Fields, the 1st novel in The Resistance Girl Series. Download them here.

This is a Giveaway with only strong women in the lead. Among them, my Agnès Duet!

Download here.

I hope you can truly stuff your E-reader or Kindle with all these giveaways and have plenty to read in 2022! Happy reading &

Happy New Year!December 19, 2021

The Norwegian Resistance Movement: The Raids

Operation Archery - the Måløy & Vaagso Raid

IntroductionThe Western Allies made a total of 57 commando raids during the Second World War against the Atlantic Wall, which the Germans had built from the Arctic Circle in Norway right down to the French-Spanish border. This was the stretch of coastline they occupied, and all the countries behind it.

These Allied raids took place before the famous 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy. Little pinpricks, but often very successful.

The raids were conducted by the armed forces of Britain, the Commonwealth and commando groups from the occupied territories serving with No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. Most of the ‘foreign’ commandos were trained for combat in the UK.

The raids became so effective that by October 1942 Adolf Hitler issued the Commando Order, which required the execution of all commandos captured. And many suffered the consequences. Alas! Incredibly brave men, each and every one of them.

The raids took place between 1940 and 1944, and were mostly against targets in France (36). There were 12 raids in Norway, 7 in the Channel Islands, 1 in Belgium and 1 in the Netherlands. They met with a mixture of fortunes.

The raids ended in mid-1944 on the orders of Major-General Robert Laycock, the chief of Combined Operations Headquarters. He suggested that they were no longer as effective, and only resulted in the Germans strengthening their beach defenses, which could be detrimental to Allied plans for the upcoming invasion.

Operation Claymore - Raid on the Lofoten

The commando raids on ‘Festung Norwegen’Norway was of vital importance to the Germans, as they needed its rich supply of iron, coal, and heavy water.

The defense of the long Norwegian coastline - Festung Norwegen as the Atlantic Wall was called here - was an immense and costly operation for the Nazis, but Hitler wanted to keep Norway under his command at any price. Not just for its raw materials, which he needed for his water machine, but also because it was strongly believed, by both the occupiers and the Norwegians themselves, that the Allied invasion would take place here.

When no invasion had happened by 1943, chances became slimmer, but, yes, there had been plans for an Nordic invasion at some point. There just was never a good moment, and conquering the rest of Europe from the North downwards wasn’t very strategic.

The most important Norwegian raidsOperation Claymore

Some 800 men, among them Norwegians, raided the Lofoten Islands on 4 March 1941. Their objective was to hit the industry. About 800,000 gallons of fish oil and glycerin were set on fire; factories were destroyed, and 228 prisoners of war were captured.

Through naval gunfire and demolition parties, 18,000 tons of shipping were sunk. Perhaps the most significant outcome of the raid was the capture of a set of rotor wheels for an Enigma machine and its code books from the German armed trawler Krebs. German naval codes could now be read at Bletchley Park, providing the intelligence needed to allow Allied convoys to avoid U-boat concentrations.

In the aftermath, the evaluation of the operation differed, with the British, especially Winston Churchill and the Special Operations Executive (SOE), deeming it a success. In the eyes of the British the main value of such actions was to tie up large German forces on occupation duties in Norway.

Martin Linge* and the other Norwegians involved, were more doubtful of the value of such raids against the Norwegian coast, but were not told of the value of the seized cryptographic information.

Following Operation Claymore, the Norwegian special operations unit Norwegian Independent Company 1, was established for operations in Norway. Later renamed the Linge Company in honor of their killed-in-combat commander, the actor Martin Linge.

* Note by Hannah Byron:

Martin Linge is one of the heroes in my upcoming book The Norwegian Assassin. He is the commander of the first mission in which Esther Weiss takes part: Operation Archery (see below). I changed his name to Magnus Linge for fictional purposes.

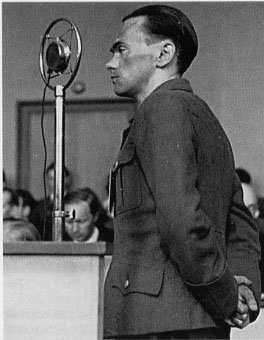

Captain Martin Linge

Operation Gauntlet - Raid on Spitsbergen

Operation Gauntlet

This was an Allied Combined Operation from 25 August until 3 September 1941. Canadian, British and Free Norwegian Forces landed on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, 650 mi south of the North Pole.

The objective of Gauntlet was to deny Germany the coal, mining and shipping infrastructure, equipment and stores on Spitsbergen and suppress the wireless stations on the archipelago, to prevent the Germans receiving weather reports.

Gauntlet was a success; the Germans were taken by surprise, the raiders suffered no casualties, the civilians were repatriated, several ships were taken as prizes and a German warship was sunk on the return journey.

Operation Archery

This raid is also known as the Måløy Raid and was a British Combined Operations raid against German positions on the island of Vågsøy, Norway, on 27 December 1941.

British Commandos, a demolition party and a dozen Norwegians from Norwegian Independent Company 1 conducted the raid. The Royal Navy, led with a cruiser and destroyers, provided fire support. Also in support were Royal Air Force bombers and fighter-bombers and a submarine. Four fish oil factories and stored were destroyed and German and Quislings (traitors) were taken prisoner.

Sadly, the Norwegian commander Martin Linge* (see above) was killed in this raid, which later led to the Norwegian Independent Company being renamed the Linge Company.

Operation Freshman

Operation Freshman - Raid on the Vemork heavy water plant

Operation Freshman, which consisted of at least 3 successive raids, is considered by many historians to be the most famous sabotage action by commandos in Norway, and possibly the greatest of the entire Second World War. It was certainly spectacular, but didn’t start off successfully.

All through WW2, the Allies feared Hitler would be able to create an atomic bomb and wipe out the City of London, or worse. One of the ingredients he needed for his bomb was the heavy water of the Vemork plant in Telemark in Norway. It seemed a race against the clock to destroy the factory, that was positioned in a valley, unable to reach over ground, or be bombed from the air, and heavily guarded by the Nazis.

Operation Grouse was the first part of the action, in which a team of 4 Norwegian commandos were parachuted into the area on 18 October 1942. They were all from the area of Telemark, where the plant situated so knew the area well. They were do to preparatory work.

The first attempt at back-up for the team in the night of 19 to 20 November 1942 failed miserable. All 32 Royal Engineers were killed either when their gliders crashed on the way to their landing zone, or survived the crash but were executed by the Germans.

But the Allies didn’t give up although on 11 December London received a message from an SOE agent explaining that the second glider's occupants had also all been shot.

Finally, in February 1943, SOE's Operation Gunnerside parachuted another six Norwegian agents into the area, to join forces with the four from 'Grouse'. They successfully attacked the Rjukan electrolysis plant on the night of 28 February-1 March 1943, with the loss of 500 kg of heavy water and destruction of the heavy-water section of the plant.*

This sabotage act was incredibly spectacular and heroic. I highly recommend watching this YouTube series from 2009, in which the raid was re-enacted with a team of British and Norwegian commandos, including interviews with the Real Heroes of Telemark and directed by Ray Mears.

*A brief and fictional version of this raid is described in The Norwegian Assassin

Coming 8 February 2022

Now on preorder

ORDER NOWThe Norwegian Resistance Movement during WW2, The Raids V

Operation Archery - the Måløy & Vaagso Raid

IntroductionThe Western Allies made a total of 57 commando raids during the Second World War against the Atlantic Wall, which the Germans had built from the Arctic Circle in Norway right down to the French-Spanish border. This was the stretch of coastline they occupied, and all the countries behind it.

These Allied raids took place before the famous 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy. Little pinpricks, but often very successful.

The raids were conducted by the armed forces of Britain, the Commonwealth and commando groups from the occupied territories serving with No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. Most of the ‘foreign’ commandos were trained for combat in the UK.

The raids became so effective that by October 1942 Adolf Hitler issued the Commando Order, which required the execution of all commandos captured. And many suffered the consequences. Alas! Incredibly brave men, each and every one of them.

The raids took place between 1940 and 1944, and were mostly against targets in France (36). There were 12 raids in Norway, 7 in the Channel Islands, 1 in Belgium and 1 in the Netherlands. They met with a mixture of fortunes.

The raids ended in mid-1944 on the orders of Major-General Robert Laycock, the chief of Combined Operations Headquarters. He suggested that they were no longer as effective, and only resulted in the Germans strengthening their beach defenses, which could be detrimental to Allied plans for the upcoming invasion.

Operation Claymore - Raid on the Lofoten

The commando raids on ‘Festung Norwegen’Norway was of vital importance to the Germans, as they needed its rich supply of iron, coal, and heavy water.

The defense of the long Norwegian coastline - Festung Norwegen as the Atlantic Wall was called here - was an immense and costly operation for the Nazis, but Hitler wanted to keep Norway under his command at any price. Not just for its raw materials, which he needed for his water machine, but also because it was strongly believed, by both the occupiers and the Norwegians themselves, that the Allied invasion would take place here.

When no invasion had happened by 1943, chances became slimmer, but, yes, there had been plans for an Nordic invasion at some point. There just was never a good moment, and conquering the rest of Europe from the North downwards wasn’t very strategic.

The most important Norwegian raidsOperation Claymore

Some 800 men, among them Norwegians, raided the Lofoten Islands on 4 March 1941. Their objective was to hit the industry. About 800,000 gallons of fish oil and glycerin were set on fire; factories were destroyed, and 228 prisoners of war were captured.

Through naval gunfire and demolition parties, 18,000 tons of shipping were sunk. Perhaps the most significant outcome of the raid was the capture of a set of rotor wheels for an Enigma machine and its code books from the German armed trawler Krebs. German naval codes could now be read at Bletchley Park, providing the intelligence needed to allow Allied convoys to avoid U-boat concentrations.

In the aftermath, the evaluation of the operation differed, with the British, especially Winston Churchill and the Special Operations Executive (SOE), deeming it a success. In the eyes of the British the main value of such actions was to tie up large German forces on occupation duties in Norway.

Martin Linge* and the other Norwegians involved, were more doubtful of the value of such raids against the Norwegian coast, but were not told of the value of the seized cryptographic information.

Following Operation Claymore, the Norwegian special operations unit Norwegian Independent Company 1, was established for operations in Norway. Later renamed the Linge Company in honor of their killed-in-combat commander, the actor Martin Linge.

* Note by Hannah Byron:

Martin Linge is one of the heroes in my upcoming book The Norwegian Assassin. He is the commander of the first mission in which Esther Weiss takes part: Operation Archery (see below). I changed his name to Magnus Linge for fictional purposes.

Captain Martin Linge

Operation Gauntlet - Raid on Spitsbergen

Operation Gauntlet

This was an Allied Combined Operation from 25 August until 3 September 1941. Canadian, British and Free Norwegian Forces landed on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, 650 mi south of the North Pole.

The objective of Gauntlet was to deny Germany the coal, mining and shipping infrastructure, equipment and stores on Spitsbergen and suppress the wireless stations on the archipelago, to prevent the Germans receiving weather reports.

Gauntlet was a success; the Germans were taken by surprise, the raiders suffered no casualties, the civilians were repatriated, several ships were taken as prizes and a German warship was sunk on the return journey.

Operation Archery

This raid is also known as the Måløy Raid and was a British Combined Operations raid against German positions on the island of Vågsøy, Norway, on 27 December 1941.

British Commandos, a demolition party and a dozen Norwegians from Norwegian Independent Company 1 conducted the raid. The Royal Navy, led with a cruiser and destroyers, provided fire support. Also in support were Royal Air Force bombers and fighter-bombers and a submarine. Four fish oil factories and stored were destroyed and German and Quislings (traitors) were taken prisoner.

Sadly, the Norwegian commander Martin Linge* (see above) was killed in this raid, which later led to the Norwegian Independent Company being renamed the Linge Company.

Operation Freshman

Operation Freshman - Raid on the Vemork heavy water plant

Operation Freshman, which consisted of at least 3 successive raids, is considered by many historians to be the most famous sabotage action by commandos in Norway, and possibly the greatest of the entire Second World War. It was certainly spectacular, but didn’t start off successfully.

All through WW2, the Allies feared Hitler would be able to create an atomic bomb and wipe out the City of London, or worse. One of the ingredients he needed for his bomb was the heavy water of the Vemork plant in Telemark in Norway. It seemed a race against the clock to destroy the factory, that was positioned in a valley, unable to reach over ground, or be bombed from the air, and heavily guarded by the Nazis.

Operation Grouse was the first part of the action, in which a team of 4 Norwegian commandos were parachuted into the area on 18 October 1942. They were all from the area of Telemark, where the plant situated so knew the area well. They were do to preparatory work.

The first attempt at back-up for the team in the night of 19 to 20 November 1942 failed miserable. All 32 Royal Engineers were killed either when their gliders crashed on the way to their landing zone, or survived the crash but were executed by the Germans.

But the Allies didn’t give up although on 11 December London received a message from an SOE agent explaining that the second glider's occupants had also all been shot.

Finally, in February 1943, SOE's Operation Gunnerside parachuted another six Norwegian agents into the area, to join forces with the four from 'Grouse'. They successfully attacked the Rjukan electrolysis plant on the night of 28 February-1 March 1943, with the loss of 500 kg of heavy water and destruction of the heavy-water section of the plant.*

This sabotage act was incredibly spectacular and heroic. I highly recommend watching this YouTube series from 2009, in which the raid was re-enacted with a team of British and Norwegian commandos, including interviews with the Real Heroes of Telemark and directed by Ray Mears.

*A brief and fictional version of this raid is described in The Norwegian Assassin

Coming 8 February 2022

Now on preorder

ORDER NOWIntroduction to the Norwegian Resistance Movement during WW2, Part V

Operation Archery - the Måløy & Vaagso Raid

IntroductionThe Western Allies made a total of 57 commando raids during the Second World War against the Atlantic Wall, which the Germans had built from the Arctic Circle in Norway right down to the French-Spanish border. This was the stretch of coastline they occupied, and all the countries behind it.

These Allied raids took place before the famous 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy. Little pinpricks, but often very successful.

The raids were conducted by the armed forces of Britain, the Commonwealth and commando groups from the occupied territories serving with No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando. Most of the ‘foreign’ commandos were trained for combat in the UK.

The raids became so effective that by October 1942 Adolf Hitler issued the Commando Order, which required the execution of all commandos captured. And many suffered the consequences. Alas! Incredibly brave men, each and every one of them.

The raids took place between 1940 and 1944, and were mostly against targets in France (36). There were 12 raids in Norway, 7 in the Channel Islands, 1 in Belgium and 1 in the Netherlands. They met with a mixture of fortunes.

The raids ended in mid-1944 on the orders of Major-General Robert Laycock, the chief of Combined Operations Headquarters. He suggested that they were no longer as effective, and only resulted in the Germans strengthening their beach defenses, which could be detrimental to Allied plans for the upcoming invasion.

Operation Claymore - Raid on the Lofoten

The commando raids on ‘Festung Norwegen’Norway was of vital importance to the Germans, as they needed its rich supply of iron, coal, and heavy water.

The defense of the long Norwegian coastline - Festung Norwegen as the Atlantic Wall was called here - was an immense and costly operation for the Nazis, but Hitler wanted to keep Norway under his command at any price. Not just for its raw materials, which he needed for his water machine, but also because it was strongly believed, by both the occupiers and the Norwegians themselves, that the Allied invasion would take place here.

When no invasion had happened by 1943, chances became slimmer, but, yes, there had been plans for an Nordic invasion at some point. There just was never a good moment, and conquering the rest of Europe from the North downwards wasn’t very strategic.

The most important Norwegian raidsOperation Claymore

Some 800 men, among them Norwegians, raided the Lofoten Islands on 4 March 1941. Their objective was to hit the industry. About 800,000 gallons of fish oil and glycerin were set on fire; factories were destroyed, and 228 prisoners of war were captured.

Through naval gunfire and demolition parties, 18,000 tons of shipping were sunk. Perhaps the most significant outcome of the raid was the capture of a set of rotor wheels for an Enigma machine and its code books from the German armed trawler Krebs. German naval codes could now be read at Bletchley Park, providing the intelligence needed to allow Allied convoys to avoid U-boat concentrations.

In the aftermath, the evaluation of the operation differed, with the British, especially Winston Churchill and the Special Operations Executive (SOE), deeming it a success. In the eyes of the British the main value of such actions was to tie up large German forces on occupation duties in Norway.

Martin Linge* and the other Norwegians involved, were more doubtful of the value of such raids against the Norwegian coast, but were not told of the value of the seized cryptographic information.

Following Operation Claymore, the Norwegian special operations unit Norwegian Independent Company 1, was established for operations in Norway. Later renamed the Linge Company in honor of their killed-in-combat commander, the actor Martin Linge.

* Note by Hannah Byron:

Martin Linge is one of the heroes in my upcoming book The Norwegian Assassin. He is the commander of the first mission in which Esther Weiss takes part: Operation Archery (see below). I changed his name to Magnus Linge for fictional purposes.

Captain Martin Linge

Operation Gauntlet - Raid on Spitsbergen

Operation Gauntlet

This was an Allied Combined Operation from 25 August until 3 September 1941. Canadian, British and Free Norwegian Forces landed on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, 650 mi south of the North Pole.

The objective of Gauntlet was to deny Germany the coal, mining and shipping infrastructure, equipment and stores on Spitsbergen and suppress the wireless stations on the archipelago, to prevent the Germans receiving weather reports.

Gauntlet was a success; the Germans were taken by surprise, the raiders suffered no casualties, the civilians were repatriated, several ships were taken as prizes and a German warship was sunk on the return journey.

Operation Archery

This raid is also known as the Måløy Raid and was a British Combined Operations raid against German positions on the island of Vågsøy, Norway, on 27 December 1941.

British Commandos, a demolition party and a dozen Norwegians from Norwegian Independent Company 1 conducted the raid. The Royal Navy, led with a cruiser and destroyers, provided fire support. Also in support were Royal Air Force bombers and fighter-bombers and a submarine. Four fish oil factories and stored were destroyed and German and Quislings (traitors) were taken prisoner.

Sadly, the Norwegian commander Martin Linge* (see above) was killed in this raid, which later led to the Norwegian Independent Company being renamed the Linge Company.

Operation Freshman

Operation Freshman - Raid on the Vemork heavy water plant

Operation Freshman, which consisted of at least 3 successive raids, is considered by many historians to be the most famous sabotage action by commandos in Norway, and possibly the greatest of the entire Second World War. It was certainly spectacular, but didn’t start off successfully.

All through WW2, the Allies feared Hitler would be able to create an atomic bomb and wipe out the City of London, or worse. One of the ingredients he needed for his bomb was the heavy water of the Vemork plant in Telemark in Norway. It seemed a race against the clock to destroy the factory, that was positioned in a valley, unable to reach over ground, or be bombed from the air, and heavily guarded by the Nazis.

Operation Grouse was the first part of the action, in which a team of 4 Norwegian commandos were parachuted into the area on 18 October 1942. They were all from the area of Telemark, where the plant situated so knew the area well. They were do to preparatory work.

The first attempt at back-up for the team in the night of 19 to 20 November 1942 failed miserable. All 32 Royal Engineers were killed either when their gliders crashed on the way to their landing zone, or survived the crash but were executed by the Germans.

But the Allies didn’t give up although on 11 December London received a message from an SOE agent explaining that the second glider's occupants had also all been shot.

Finally, in February 1943, SOE's Operation Gunnerside parachuted another six Norwegian agents into the area, to join forces with the four from 'Grouse'. They successfully attacked the Rjukan electrolysis plant on the night of 28 February-1 March 1943, with the loss of 500 kg of heavy water and destruction of the heavy-water section of the plant.*

This sabotage act was incredibly spectacular and heroic. I highly recommend watching this YouTube series from 2009, in which the raid was re-enacted with a team of British and Norwegian commandos, including interviews with the Real Heroes of Telemark and directed by Ray Mears.

*A brief and fictional version of this raid is described in The Norwegian Assassin

Coming 8 February 2022

Now on preorder

ORDER NOW