Robert Matzen's Blog

February 16, 2025

They Were Giants

After the rape of Ann Sheridan’s character by a German soldier, Resistance leaders led by Errol Flynn plan revenge in Edge of Darkness.

After the rape of Ann Sheridan’s character by a German soldier, Resistance leaders led by Errol Flynn plan revenge in Edge of Darkness.I’m working on a new book idea involving World War II, and two motion pictures I’ve watched recently on Netflix tangentially touch on my topic.

Narvik, made in 2021, depicts Norwegian civilians in the town of Narvik who watch the Germans march in as occupation begins in 1940. But they won’t accept life under Nazi rule, which leads to an epic battle that marks what came to be known as Hitler’s first military defeat. Fictional characters—Gunnar and Ingrid Tofte—form the emotional core of this real-life and very true-to-history story. He’s a member of the Norwegian army and his company takes to the hills after German occupation, while she’s trapped in town and serves as an interpreter between the occupiers and town officials.

Number 24, a Norwegian production, shines devastating light on Nazi occupation as seen through the eyes of Gunnar Sønsteby.

Number 24, a Norwegian production, shines devastating light on Nazi occupation as seen through the eyes of Gunnar Sønsteby.The other and more recently made movie, Number 24, relates the true story of the most successful Resistance fighter of the Norwegian occupation, Gunnar Sønsteby, a young accountant so nondescript in appearance that the Germans don’t consider him a threat—until continued Resistance activities finally put him in the crosshairs. Through meticulous planning and single-minded purpose, he becomes the key Resistance leader in Oslo and an MI-6 operative for the British government, codenamed “Number 24.” The first half of Number 24 is so unrelentingly tense as Sønsteby tries to evade capture that I didn’t think I’d make it through the next minute, and the second half, full of redemption as Sønsteby begins a vengeance campaign to take out top Nazis, feels better than it probably should as one after another they’re gunned down without mercy.

Both pictures serve as reminders about the brutality of the Nazi empire, and both put me in mind of one of my favorite Errol Flynn pictures, Edge of Darkness, made in 1942 and released early the next year with the war very much in doubt from an Allied perspective. Edge of Darkness also tells a story of the Norwegian Resistance, this time in the fishing village of Trollness. And while much of it was shot in the Burbank studio and on backlots, with the northern California town of Monterey filling in for exteriors, Warner Bros. managed to accurately capture life 5,000 miles away in a country forced to live under the swastika. Imagine a 1943 picture that served up the Norwegian heroine raped by a German soldier; a sympathetic Norwegian woman attracted to a different, sympathetic German soldier; townspeople forced to dig their own graves prior to their execution; and a battle of annihilation that wipes out not only the Germans but most of the villagers.

In all three pictures, the Germans get their comeuppance, and what a triple feature these three would make. Each rings true to an overlooked aspect of history, even though their production spanned 82 years. Enough attention doesn’t get paid to Norway, which—while tucked away off the beaten path of the European war—played a major role in its evolution. Norway was of strategic importance for its iron ore, as shown in Narvik, and the country saw successful raids by British commandos soon after the occupation began, raids that drove Hitler crazy as did the revolt in Narvik. He became so obsessed with what he felt was a looming British invasion of Norway that he stationed 350,000 troops there for the duration of the war—troops that were not therefore available to stem the tide when the Allies invaded France in June 1944.

Another Norwegian release captures the heroism of the Resistance during the epic 1940 battle for the port of Narvik.

Another Norwegian release captures the heroism of the Resistance during the epic 1940 battle for the port of Narvik.The question “What’s the price of freedom?” is both spoken and unspoken in each of these films. You’re either occupied by a foreign power or you’re free. The principals in all three choose to fight for their freedom and do it in ways true to the individual. A scene in Narvik shows Norwegian soldiers, who have just taken a hill from the Germans with the help of French allies, pulling down a Nazi flag and running up the Norwegian colors. It’s a very Edge of Darkness moment and mirrors a scene when Ann Sheridan takes aim with a rifle and shoots a Nazi who’s trying to raise the swastika over her town. “Free Norway!” Judith Anderson shouts into the telephone to Nazis at one point during the Trollness revolt. And when during a Resistance meeting one of the plotters thinks about how their work will be remembered, he growls that history will proclaim, “They were giants in Trollness!”

Oh my God, do I find such stories thrilling! I’m grateful that these two recent productions have focused on the Norwegian Resistance, with both Number 24 and Narvik benefitting from Norwegian productions, actors, and exteriors. This is Norway proudly reclaiming its history, a rich, heroic history that the world needs right now as right-wing authoritarianism threatens various points around the globe. The message of all three movies is singular and compelling: People who have lived free want to remain free and will prove unwilling to settle for others making decisions for them.

Edge of Darkness: The final, seemingly doomed assault on German machine gun emplacements by the Resistance fighters of Trollness.

Edge of Darkness: The final, seemingly doomed assault on German machine gun emplacements by the Resistance fighters of Trollness.

February 2, 2025

Tension in the Workplace

Get away from me, you psycho bastard.

Get away from me, you psycho bastard.It’s been a long time since I had a co-worker of the opposite sex I just couldn’t stand. As in despised. Reviled. Back when I did, it was a good thing I didn’t have to embrace and kiss that person passionately and profess my love as part of my job. So, imagine you’re an actress on an MGM soundstage working with an actor you loathed, like Eleanor Parker working with Stewart Granger.

The picture they made together, Scaramouche, is a Sabatini novel of revenge set in eighteenth-century France during the Revolution. At the turn of the 1950s, as MGM began turning out Technicolor costume adventures by the bucketful to compete with television, Scaramouche seemed a natural fit, following up on a silent version starring Ramon Novarro released back in 1923.

As usual, I’m not going to review Scaramouche except to say I find it a terrific picture in the classic sense of a vengeance swashbuckler with a couple of neat plot twists at the end. Some of you may know I’m not a fan of Mel Ferrer the movie star or the human being, but I’m the first to say he’s perfect as the antagonist in this picture, the Marquis de Maynes. Everyone’s really good in it, and the plot moves at a breakneck pace.

Headliner Stewart Granger had recently come to the States after a string of successful pictures in the UK, and his first big MGM picture in Hollywood, King Solomon’s Mines, had been a smash. So next he would star in Scaramouche opposite former Warner Bros. leading lady Eleanor Parker, whose contract had not been renewed, resulting in a move to MGM. She played the worldly wise firebrand actress Lenore, who loves and hates Andre Moreau, a self-centered aristocratic reprobate played by Granger. The onscreen relationship between Granger’s Moreau and Parker’s Lenore is tempestuous and disguises a natural animosity that existed between the players.

My pal Dick Dinman interviewed Parker in the 1990s, with Granger as one of the topics of conversation. “I can’t even say his name, I dislike him so much,” Parker began before blurting out, “I hated the man.”

Young Janet Leigh never looked better.

Young Janet Leigh never looked better.Then she went on to describe a pivotal moment between the actors, a confrontation that took place in a covered wagon: “I had to slap him once in a scene. Slap his face. And he said, ‘If you ever hit me while we’re doing this, if you slap me, I’m going to grab your throat and I’ll kill you.’ He said, ‘I almost killed…’ some British actress and he named her name—I can’t remember who it was now—but he said, ‘I grabbed her by the throat and I almost choked her to death.’ I said, ‘Oh, how nice.’ And he said, ‘If you dare to slap me and hurt me at all, I’m going to do it to you.’ He said, ‘I mean it.’ Oh, he was so mean. My mouth dropped open and I wanted to hit him right then. So the scene came up and we were doing his close-up or whatever and you had to see him get slapped…and I went [she grunts faintly] and my hand went up and back. I just couldn’t hit him; he’s looking at me and I couldn’t hit him. He looked proper because he couldn’t glower at me with his face to the camera. So I didn’t want to hit him.

“The director [George Sidney] said, ‘Cut! Eleanor, what’s the matter with you?’

“I said, ‘I want to talk to you for a minute.’”

Him: “You fancy me.” Her: “No, I hate you.”

Him: “You fancy me.” Her: “No, I hate you.”They went off by themselves and she told him, “He threatened me. He’s going to grab me by the throat and kill me if I…slap his face, and I don’t know what to do.”

George Sidney said, “He’s a coward. Never mind him. Hit him as hard as you can. Don’t worry. All the crew—everybody, we’re right here to grab that man and kill him if we have to. You just hit him as hard as you can.”

They played the scene and she gave him a stage slap as instructed.

“When they said ‘cut,’ he looked at me, turned around, and he never spoke to me for the rest of the movie. He didn’t do anything, but he never spoke to me. If I walked up and he happened to be in a group, he would turn around and leave or he would stop talking and just stand there until I left. It was most embarrassing. And that’s all I was doing, what the director told me, and I had to do it because it’s written in there [in the script].”

Hearing this story from Parker years ago soured me on Granger, and nothing I’ve heard since really counters the impression she gave of the man. He did indeed have a reputation as a cold narcissist, and what strikes me now watching him is a naked attempt to copy the style and mannerisms of Errol Flynn, which he couldn’t do because he didn’t have Flynn’s charm. Parker had co-starred with Flynn twice and, despite Errol’s bad-boy reputation, said he was a pro on the set and always respectful—never the malevolent presence she described in Stewart Granger. She summed it up saying, “He was so awful, the rudest, nastiest guy; I just hated him. Everybody did.”

To Dick Dinman’s great credit, when he interviewed Stewart Granger, he asked him about the alleged difficulties with Eleanor Parker on the set of Scaramouche. “I don’t know what it was,” said Granger, “but she had great pleasure in smacking me, really belting me as hard as she could. I mean, she didn’t pull her punches. Normally we actors and actresses pull our punches; we slap it away. One scene where I’m sitting on a basket and I’m joking with her and being difficult and she says, ‘Oh, you!’ and she goes and knocked me out. She hit me so hard that for two seconds I can’t think where I am.”

Well, yes, Mr. Granger. You threatened her and the director urged her to let you have it, with 30 or 40 crewmen as backup.

But his next comment revealed the kind of misogynist that ruled in Hollywood at the time: “There were problems with Eleanor Parker. She was a darling, but she was—I guess I was a bit of a naughty fellow, you know. [I] wouldn’t play ball in the way she—I don’t know what it was, but she seemed…you know, a lot of women like to slap men really hard, especially if they fancy you. And I think maybe she fancied me in those tights.”

Hats off to both Ferrer and Granger for a commitment to excellence making this swordfight sizzle.

Hats off to both Ferrer and Granger for a commitment to excellence making this swordfight sizzle.Um, sure, Stewart. She must have fancied you because you were irresistible in tights. Never mind the threats of murder.

Given that I’m not a fan of Mel Ferrer and I’m not a fan of Stewart Granger, Scaramouche remains for me a hoot. It’s one of those pictures that’s been sort of lost to the ages and definitely one where you need to suspend your disbelief. But, boy, the furious chases on horseback, the lush Technicolor with Janet Leigh in her prime and Parker’s flaming red hair, and the six-and-a-half-minute climactic swordfight in a theater that’s equal parts athletic and deadly, make this for me the best of the 1950s. And knowing of the tension between the leading man and his co-star makes for interesting sport as you watch them work together, especially in that scene in the wagon.

But you know what’s funny? That one female co-worker I just couldn’t stand back in the day is one I now look back on with fondness, understanding in hindsight that I generated a lot of the conflict by being young and full of myself. It doesn’t seem that any such self-reflection ever made it into the mind of the late Stewart Granger.

December 29, 2024

One Little Gem

My friend Tom sent me a link the other day. He had found a six-minute YouTube video on the topic of a particular shot in the movie Casablanca and thought I would be interested in seeing it since my last book, Season of the Gods, told the day-by-day, way-behind-the-scenes story of the creative minds who got together and spun this 1942 cinematic masterpiece. The other reason Tom sent it to me is that he made a long, successful career as a film and video editor who taught me most of what I know about the craft, and the shot in question from Casablanca involved editing at its best—or rather, the shot represented a brilliant example of editing forbearance.

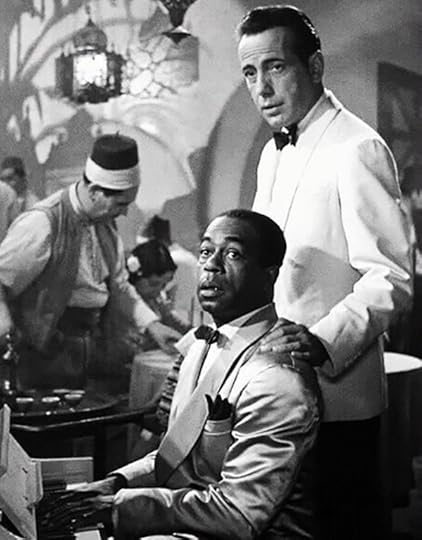

At plot point one in the picture, Rick sees Ilsa for the first time since Paris. Right before that encounter, Ilsa tells Sam the piano player that she wants to hear the song As Time Goes By. He starts to play, and she says, “Sing it, Sam.” As he starts to sing the song, the camera fixes on Ilsa’s reaction to hearing it. The last time I watched the picture, which I’ve seen many times, including on the big screen, the length of the shot struck me. It’s 25 seconds long, which is an eternity of screen time, particularly for a director like Michael Curtiz, who likes to keep things moving as he pushes his story forward, ever forward. But here, nothing happens in 25 seconds—and everything happens in 25 seconds.

Ilsa listens to As Time Goes By and remembers her love affair with Rick in a 25-second shot.

Ilsa listens to As Time Goes By and remembers her love affair with Rick in a 25-second shot.The shot reveals that the past tortures Ilsa, but she must hear the song and dive headlong into her pain. As revelatory as the shot is, it’s also a director’s gamble since executive producer Hal Wallis might just notice the extraordinary length and fire off a memo to Curtiz to stop doing that! Or studio boss Jack Warner might send a memo along the same lines. Stop wasting film and money on these long takes!

As noted in the YouTube video, the shooting script of Casablanca didn’t mention a long, lingering close-up of Ilsa. The script simply shows Ilsa’s line, and describes Sam singing, and the stage direction has Rick walk in and see Ilsa. So, this was a Curtiz idea on the spot, and I can imagine how it came about. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, a veteran of moviemaking going back 30 years and also a still photographer, had adjusted his lighting just right on Ingrid Bergman playing Ilsa. The setup caught a glint of light off her right eyeball and a glint of light off her left tear duct. They rehearsed the scene as written—she tells Sam to sing the song and Sam reluctantly complies. Edeson shot it over Bergman’s shoulder to Dooley Wilson as Sam, and over Dooley’s shoulder to her, and in a close-up of Bergman asking him to sing the song and then her reaction to it.

Here Curtiz or maybe Arthur Edeson noticed something special—Bergman’s inspired reaction to what she was hearing. Ingrid Bergman would create this great mythology later in life that she didn’t understand Casablanca or her character or whom she should be in love with—Victor Laszlo or Rick Blaine. But this shot reveals the big lie of all that nonsense. As crafted by director Curtiz, and shot by Edeson, and acted by Bergman, Ilsa knew exactly whom she loved. It’s written all over her face through 25 seconds. Ilsa loved Rick and Ilsa wasn’t over Rick.

Bergman had a remarkable ability to play it vulnerable her whole career, and in rehearsal Curtiz must have seen how powerfully Bergman was communicating a lost love, or Edeson perhaps noticed first, and director and cameraman would have conferred, and then for the close-up, I can hear Curtiz saying to her, “Think of something sad. Keep thinking about something sad.” He might have coached her through those 25 seconds knowing the song would be looped in separately.

After her reverie, Rick appears and she gazes up at him, her eyes moist as beautifully lit by Arthur Edeson.

After her reverie, Rick appears and she gazes up at him, her eyes moist as beautifully lit by Arthur Edeson.Then I wonder what was her motivation; what was the sad thing she thought about? What came to mind was Ingrid Bergman’s recent exile in Rochester, New York, where she had spent an unhappy winter in deep snows waiting for the phone to ring with David O. Selznick at the other end of the line. Selznick owned her services at this time but kept not finding parts for her. So, the time dragged by for Bergman in snowy Rochester—3,000 miles from Hollywood—while her dentist husband progressed through a medical internship. She had gone into this period excited at the prospect of serving as a dutiful housewife, but then the reality hit her how out of place she was, how out of work she was, and the snow piled up, and letters to a friend revealed how deeply unhappy and then depressed she had grown during these months, feeling that Selznick had abandoned her, feeling she would never work again.

Whatever motivated her, the camera loved it and the director loved it, to the extent that this one shot would make it through Owen Marks’ editing booth intact at 25 seconds. Marks was an experienced hand with many Warner Bros. A-pictures under his belt, but he would not have made such a decision on his own. Curtiz must have fought for the length of this shot and Wallis must have OKed it, because 10 seconds would have been safer, 15 tops. But on it goes, uncomfortably so, until suddenly you realize you’ve strayed too deeply into Ilsa’s pain.

It’s one little gem in a treasure chest of a picture. It’s also an interesting decision by two or three or four of the gods in their season who came together to create a masterpiece.

__________

Season of the Gods is available in trade paperback through Barnes & Noble and Amazon.com. It’s also a dynamite audiobook read by Holly Adams.

Plot point one: Rick sees Ilsa and his face hardens with contempt. She’s vulnerable; he’s contemptuous, and the story spins in a new direction.

Plot point one: Rick sees Ilsa and his face hardens with contempt. She’s vulnerable; he’s contemptuous, and the story spins in a new direction.

December 1, 2024

Superhero Audrey

My book Warrior: Audrey Hepburn proved to be one of many casualties of the Pandemic. Warrior dropped in 2021 and because of the lockdown, because the stores were closed or not holding events, I couldn’t go out and tour in support of the book and so Warrior hit the water without making a splash. What a shame that is, because Warrior tells the story of the Audrey that her son Luca Dotti wanted the world to know about, the woman who took all the lessons learned during her World War 2 years spent under German occupation and applied them to helping those in need in war zones. Like a superhero, she would don helmet and flak vest and go on a UN mission into the middle of somebody’s civil war to advocate for children caught in the crossfire, and the next week show up in Givenchy at a New York or Hollywood gala with the rich and famous to raise funds for UNICEF.

I was reminded of Warrior and its subject when I saw a photo on Facebook of Audrey with her pal Gregory Peck at a November 1988 gala at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City. This was after Audrey had gone to war-torn Ethiopia, where on landing she looked out the window of the plane to see Soviet MiGs parked on the runway and manned artillery batteries beside them. Welcome to life as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador! The first night on the ground there was spent in a bombed hotel with armed guards and no electricity, which caused the star not to bat an eye because she had spent weeks with no lights or running water in the Netherlands as the war ground to a conclusion in spring 1945.

The meeting with Peck also took place after Audrey’s most recent mission to Venezuela and Ecuador, which proved a walk in the park compared to what lay ahead in places like South Sudan where she faced machine gun fire, Vietnam where she charmed the general who had defeated the U.S. military, and Somalia where she impressed skittish Marines with her cool composure on the front lines.

Look at that face! This is the unknown Audrey, shy, a bit goofy, and always deferential with her daunting friend Greg. They had met 36 years earlier on location to make Roman Holiday and by that time 36-year-old Gregory Peck was a four-time Best Actor nominee while 23-year-old Audrey was taking her first stab at a full bells-and-whistles Hollywood production. She knew precious little about acting, had not honed her craft on the stage, and had hurried through a handful of screen appearances in UK pictures, usually as a walk-on. She spent the production of Roman Holiday terrified, which makes the performance coaxed out of her by Peck and director William Wyler all the more remarkable. How the heck do you win an Oscar as Best Actress your first time out under those conditions? If you asked Audrey, she would shrug her shoulders and give that same enigmatic smile—she just didn’t know.

Hepburn and Peck during the terrifying location shoot of Roman Holiday 36 years earlier.

Hepburn and Peck during the terrifying location shoot of Roman Holiday 36 years earlier.Audrey Hepburn believed in luck. She had been very lucky during the war, like the time a German soldier shoved her under a tank as a British Spitfire stitched the pavement beside her with machine gun fire. Or the time she escaped Dutch Green Police who were rounding up girls to send to Berlin as forced labor. Or the many times she ran food and messages to Allied airmen on the run. She and her housemates were certainly lucky not to die in the artillery barrages that followed the battle for Arnhem or the misfiring V-1 rockets that fell on her village instead of their target of Antwerp. She was lucky not to die in the notorious Hunger Winter that killed 20,000 Dutch, although she came damn close.

I find it hilarious that Audrey spent her lifetime intimidated by Gregory Peck, who had sat out the war with “back trouble.” Hmmm. He sure didn’t have trouble hoisting himself into a B-17 while making Twelve O’Clock High, now did he? But that’s the beauty of Audrey: the inner beauty. She was brave and kind to a fault. No, really, to a fault. If you had a cold and Audrey was around, she would nag you back to health, and in the process nearly drown you in chicken soup. Every fan that didn’t get an autograph clouded her mind with guilt. Unlike just about every star around her, Audrey never “went Hollywood.” It wasn’t in her DNA.

All that came to mind when I saw this 1988 photo of Audrey and Greg at the Waldorf-Astoria and relived marathon conversations with Luca about his down-to-earth mother who also just happened to be a superhero.

Audrey on a U.S. Marine helicopter inbound to Mogadishu Airport, September 1992.

Audrey on a U.S. Marine helicopter inbound to Mogadishu Airport, September 1992.

November 10, 2024

The Big ‘However’

It’s baffling to me to think that in my lifetime, there was a thing called segregation. In my lifetime! I wasn’t old enough to actually see a restroom or swimming pool for “colored people,” so when I’m reminded that even in the 1960s things were that way, I’m stunned. All of which points out to me the twentieth century trailblazers who wouldn’t settle for the two-tier system in America, such as Warner Bros. executive producer Hal Wallis. As detailed in my book Season of the Gods, Wallis despised studio boss Jack Warner, whose narcissism clashed with Wallis’s own fearsome ego. One of the things they clashed over was Black talent.

Hal Wallis (right) with Casablanca director Michael Curtiz and Ingrid Bergman.

Hal Wallis (right) with Casablanca director Michael Curtiz and Ingrid Bergman.Years ago, while combing the U.S.C. Warner Bros. Archives, I came across a summer 1941 Jack Warner memo indicating he wanted some “colored people” for comic relief in the Custer biopic then in development starring Errol Flynn. Warner was an advocate of comic turns in all the WB pictures—they called them “bits of business” back in the day—always done by white character actors like George Tobias or Alan Hale, or by Black actors like Clarence Muse. In the case of the Custer picture, the Jack Warner memo resulted in the appearance of a “boy” tending Custer’s hounds at the beginning of the picture, and new scenes for housekeeper “Callie” played by Hattie McDaniel, then not far past her Academy Award win for Gone With the Wind. McDaniel’s Oscar, richly deserved for a nuanced performance as Mammy, had sent shock waves through the continent—America wasn’t ready to recognize 1) a Black character as wiser or more grounded than the white characters in the piece, or 2) a Black performer as talented as Caucasian counterparts.

Hattie McDaniel with the teacup ‘bit of business’ in They Died with Their Boots On (1941).

Hattie McDaniel with the teacup ‘bit of business’ in They Died with Their Boots On (1941).I don’t know about you, but McDaniel’s bits of business in the Custer picture They Died with Their Boots On have made me uncomfortable for decades—the bit about the fortune telling with the teacup and rabbit’s foot and the thing in the garden with the owl. Yikes. But that was Jack Warner for you, always ready to beat people over the head with painful humor delivered in person through notoriously horrendous jokes or through his pictures of the 1930s and 40s, none of which I find funny. Whether it’s Boy Meets Girl or Arsenic and Old Lace, the humor is loud, desperate, and, to me at least, painful.

But back to the Hal Wallis–Jack Warner enmity. Wallis acquiesced to Warner in the case of Custer, but times were changing. At the turn of 1942, with America newly launched into world war, Wallis bought a stage play called “Everybody Comes to Rick’s” and jammed it into the production schedule, renaming it Casablanca. A key member of the cast was a gay “Negro” piano player called Sam the Rabbit, who was written as a stereotype of the times. However, in developing the characters and screenplay of Casablanca in February and March 1942, Wallis was seeing headlines like this one in Daily Variety: BETTER BREAKS FOR NEGROES IN HOLLYWOOD. Dated March 24, the article began, “Negroes are to be given an increasingly prominent part in pictures,” according to Walter White, head of the NAACP. White stated that “Darryl Zanuck and other production chiefs had promised a more honest portrayal of the Negro henceforth, using them not only as red-caps, porters and in other menial roles, but in all the parts they play in the nation’s everyday life.”

Dooley Wilson as Sam, Rick’s loyal BFF.

Dooley Wilson as Sam, Rick’s loyal BFF.Hal Wallis embraced this controversial new approach, reasoning that “Negroes” were fighting and dying for their country in the war, spilling the same color blood as white people, so why not treat them as equals in pictures? First up was the role of Parry played by Ernest Anderson in the Bette Davis sudser, In This Our Life (1942). Parry was the young son of a household cook (Hattie McDaniel again) who was wrongly accused of a fatal hit-and-run accident. He’s cleared by the end of the picture and off to law school—and throughout, his part isn’t played for laughs. At all. And with Casablanca, Wallis considered the same approach—taking the character seriously. Wallis considered writing Sam as a woman and casting either Hazel Scott or Lena Horne until studio story editor Irene Lee and writers the Epstein twins won Wallis over that Sam must be a male to head off any thought that Rick and his piano player might be romantically involved—which would sap the intensity of the Rick–Ilsa dynamic.

Over time, veteran Black character actor Clarence Muse was considered for the part of Sam, and Hollywood newcomer Dooley Wilson was chosen. All the while, Jack Warner played rooftop sniper and argued against letting Sam be played as Rick’s best friend and confidant because the picture might be banned in the American Deep South for showing a Black man as Rick’s equal. And Wallis kept pointing to the war effort and the changing times, stuck to his guns, and gave the world a character for the ages in Sam, a role and a performance that holds up 100 percent today, going on a century later. There isn’t one false note in Dooley Wilson’s characterization, not one cringeworthy moment of the kind that mar Hattie McDaniel’s performances—bits forced upon her to reassure white viewers they were indeed superior.

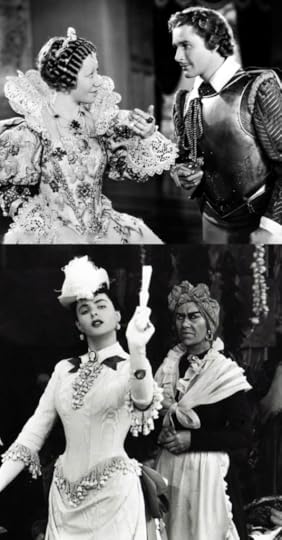

Flora Robson as Queen Elizabeth with Flynn in The Sea Hawk (1940); Robson as a Black slave with Ingrid Bergman in Saratoga Trunk (made in 1943; released in 1945).

Flora Robson as Queen Elizabeth with Flynn in The Sea Hawk (1940); Robson as a Black slave with Ingrid Bergman in Saratoga Trunk (made in 1943; released in 1945).Now we come to the big “However.” Just months after Casablanca wrapped, Wallis started work on a picture called Saratoga Trunk, from the novel by Edna Ferber. The lead role of Clio Dulaine in Saratoga Trunk was coveted, much as had been the part of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. I remember how badly Olivia de Havilland in particular wanted to play illegitimate, half-Black Clio returning from France to post-Civil War New Orleans to avenge her mother. But do you know who Hal Wallis chose for Clio in Saratoga Trunk? Fair-skinned Swede Ingrid Bergman, that’s who, her hair dyed black to “satisfy” the problem of race. And for the part of Clio’s Black maid Angelique, Wallis selected very white, British-born Flora Robson, who just three years earlier had portrayed Queen Elizabeth I in Flynn’s The Sea Hawk! For Saratoga Trunk she’s slathered in hideous dark-skinned makeup because, Wallis said, “the role was so large and important that it was beyond the range of many [Black] actresses of that time.” Um, OK, Hal. Sure. Ironically enough, Robson would be nominated for an Oscar for her take on Angelique, whereas today, viewers simply take one look at her, gasp, and go, “Wut up with the blackface?” So, sometimes Wallis challenged the norms and sometimes he didn’t; after all, Wallis straddled the line between artist and businessman. When he got it wrong, the result was Saratoga Trunk, a picture known only to die-hard cinephiles. When he got it right, the result was Casablanca with its many perfections, not the least of which is quiet, steadfast Sam, best friend of the white guy. (And I’ll bet you Rick’s Café Americain didn’t hold even one segregated restroom.)

October 27, 2024

Questioning Why

Lawman moves to syndication sporting great numbers.

Lawman moves to syndication sporting great numbers.I work at a communications firm with a lot of younger people who are always talking about the latest movie or series they’re consuming. They get so excited talking about it, and one will mention a title and three others will chime in with enthusiasm. They don’t seem to notice that I’ve gone mute and averted my gaze because I have no idea what the hell they’re talking about and have nothing to contribute to the conversation. I remember the time the owner of the company came into my office maybe 15 years ago and asked me what my favorite television show was at that time, and I said, Cheyenne. She’s older than I am and started singing the theme song from Cheyenne, a western that ran from 1955 to 1962. Even then my boss thought it was funny that my favorite show was 47 years old. Yes, I continue to be trapped here in—wait, what year is it?—while my psyche lives in the dim and distant past. When I read a book, it’s about the Civil War or WWII; when I watch TV, it’s nothing that was made after 1975. You get the idea.

What’s your point, Robert? OK, my point isn’t anything about Lawman, per se. My point is about the nature of addiction, and are addicts born or made? Do you decide one day that you can’t live without your liquor or pills or chocolate? Or are you born with these unquenchable desires? I watch Peggie Castle on Lawman when she was 33 and 34 looking for clues about the addiction that would go on to kill her a decade later: hardening of the arteries and cirrhosis of the liver. She strikes me as such a tragic figure, this tall and willowy blonde who, you would think just by looking at her, had the world by the balls. For all I know after some quick research, Peggie Castle’s biggest problem at the time of Lawman was trouble keeping weight on to the point that her diet featured mainly pasta. Were those bags under her eyes a hint at late nights on the bottle? Or trouble sleeping caused by worry that would go on to cause the drinking?

One of my favorite shows is Lawman, a Warner Bros. western in production from 1958 to 1962. Lawman featured John Russell as Marshal Dan Troop of Laramie, Wyoming, who could draw pretty fast but lived more by an unwavering moral compass. Season one went well for Lawman in a booming period for television westerns, so for season two they decided to write in a love interest for Dan Troop (a couple of prospects had washed out in season one because of lack of pizzazz and chemistry with Russell). Warner Bros. hired 32-year-old Peggie Castle for the role, she the star of some noir B and costume pictures made throughout the 1950s. Sure, she had some roles in A pictures, but more often she made an impression as the “other woman” who was murdered in the second reel. The nasty film noir 99 River Street comes to mind.

Peggie Castle (left) in pre-Lawman days, vixen and murder victim in 99 River Street.

Peggie Castle (left) in pre-Lawman days, vixen and murder victim in 99 River Street.Four marriages by age 30 (the first in 1945 at 18 to a serviceman) make one suspect a capricious person, or an unhappy one looking for a stability she couldn’t muster on her own. The fact that she made her last motion picture right before Lawman and left television at the show’s cancellation in 1962 speaks to a general lack of ambition, or a need to get away from a Hollywood that seems to have been pretty good to her over the course of 12 years of steady work.

Russell as Lawman Troop; Castle as saloon owner Lily Merrill. Studio flak hinted at onscreen wedding bells in season four.

Russell as Lawman Troop; Castle as saloon owner Lily Merrill. Studio flak hinted at onscreen wedding bells in season four.After Lawman, Peggie Castle would make just one more appearance in series television, a walk-on in a 1966 episode of The Virginian that was shocking for a couple of reasons. Her part as a dance-hall girl amounted to one scene that had nothing to do with the plot; it was something obviously written as a favor or a motivator, probably with ex-husband William McGarry pulling the strings. McGarry served as a long-time assistant director with a career that went back to To Be or Not to Be with Carole Lombard in 1942, and his many credits include Breakfast at Tiffany’s with Audrey Hepburn. (Oh, by the way, I wrote books about both actresses. Fireball. Dutch Girl. Warrior.)

I gasped the first time I saw Peggie Castle in this scene in The Virginian that was shot around the holidays 1965. Three and a half years had passed since Lawman wrapped production in May 1962, and Castle now looked like absolute hell, sporting what appears to be a black eye. They could cover that left cheek with makeup, but the swelling was another story.

Last glimpse of Peggie Castle–a one-scene curio on The Virginian.

Last glimpse of Peggie Castle–a one-scene curio on The Virginian.If somebody were to write a book about Peggie Castle, I promise to buy it to learn what story arc set this woman on a path of self-destruction that ended when ex-husband McGarry found her sitting on the couch in her Hollywood apartment, dead at age 45. In an era when players earned no residuals for their movie and TV work, how did she pay rent for that apartment? How did she buy enough booze to wreck her body so fast? Most importantly, why did she lose the desire to live and work and need to be anesthetized 24/7? Did Hollywood kill her as it has taken so many others, and if she had never left Appalachia, Virginia, would everything have been different?

Lots of questions and no answers as I sit trapped in time watching Lawman.

July 2, 2024

Play it!

Note: Season of the Gods is available in trade paperback and ebook formats at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, the independent Bookshop.org, and other book retailers. The audiobook version was read by the superb Holly Adams.

I wrote Season of the Gods with the intention of forcing people to look at the Warner Bros. classic Casablanca in a new way. I wanted to challenge you, the reader, to think about the screenplay and the plot and the dialogue and the environment in which Casablanca was created because it’s simply a miraculous motion picture, and how in the world did it come about? First of all, I needed to understand the how and the why of it myself, and then my plan was to take the results of my research and lay it out in story form. The fact that Season of the Gods is categorized as “historical fiction” is strange to me since the characters are real people, and everything they do in the book is based on research.

Did you ever notice the undercurrent of tension in Casablanca? I just watched it again a couple of evenings ago and some new things occurred to me, which is always happening with viewings of the picture since there’s so much filling the frame every moment. I was watching the scene where the German officers are singing in Rick’s and an outraged Victor Laszlo storms over to the band and orders that “La Marseillaise” be played. What are we, an hour in when this happens? “Play it!” snaps Laszlo, mirroring Rick’s earlier order to Sam to play “As Time Goes By.” “You played it for her, you can play it for me,” Rick had said. “Play it!”

With Victor standing in front of the band, the musicians look to Rick for guidance, and Rick gives the nod to follow Laszlo’s instructions and they start playing. I’m not telling you anything new when I point out the power of what follows because it’s the biggest emotional payoff in the picture. But why does it work so well? Why does it make me cry every time I see it?

Well, in screenplay terms, let’s FLASH BACK TO WARNER BROS. SOUNDSTAGES, JUNE 1942. There’s a bit in Season of the Gods where Bogart and Lorre are relaxing in Bogart’s dressing room and Bogie snaps on the radio to hear the latest about the battle of Midway as if he’s checking the box score on a baseball game. At the time of Midway, the Japanese navy was at the peak of its power, its carriers a mysterious and untraceable menace on the high seas that six months earlier had taken out most of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Meanwhile, Europe was squeezed ever tighter in the grip of the German Reich. There’s another bit in Season of the Gods where Hal Wallis learns that 5,000 of the best and brightest Jews in Paris had been rounded up and shipped off to concentration camps. These weren’t peasants from Romania; they were the upper class of Paris, and the Germans had pounded open their doors and ripped these Parisians from their beds. All of a sudden Wallis realizes, holy shit, that could happen here!

Conrad Veidt had fled his native Berlin because his wife was Jewish. During his Hollywood career he gladly played Nazis to expose their evil.

Conrad Veidt had fled his native Berlin because his wife was Jewish. During his Hollywood career he gladly played Nazis to expose their evil.This was the world at the time Wallis and crew produced Casablanca in May and June 1942. In past columns I’ve described how Wallis and Mike Curtiz populated the backgrounds of the picture with refugees who had recently fled the German menace—all of them Jews or married to Jews and most of them big stars in their native countries who suddenly felt grateful to get a day or a week on an American picture. For these people, the story told in Casablanca was all too real and none of them needed direction in the script to understand their motivation. A year or two or three earlier, they had lived desperate moments on the point of a knife, not knowing if they would make it to freedom. Now they were reenacting those moments for the camera, for posterity, in Hollywood. It’s amazing how many Americans were not in Casablanca.

Bogart, Dooley Wilson, and Joy Page were native-born Americans. Rains and Greenstreet were Brits and for them, box scores involved the latest German air raid. Bergman was a Swede and Lorre and Sakall Hungarian; both had left Europe because of the Nazis. Conrad Veidt was German and had fled Berlin with his Jewish wife. Madeleine LeBeau (Yvonne) and her Jewish husband Marcel Dalio (Emil the croupier) were newly arrived after escaping France via Portugal and Mexico. Austrians Ilka Grüning and Ludwig Stössel portrayed the couple trying to learn English so they would fit in in America. “What watch?” he asks her, meaning What time is it? “Ten watch,” she answers. Both were accomplished performers in Europe (she had worked for Reinhardt and acted with Garbo!) who had fled Hitler and—in their mid-60s—starting over in Hollywood. All of these people, all of them, had already seen family and friends rounded up and sent to camps. In fact, Austrian Helmut Dantine (Jan in the film), had been involved in anti-Nazi youth group and the Germans sent him to a concentration camp; only the quick thinking of a family member got him released and packed off to the United States.

Ludwig Stössel and Ilka Grüning had been born in Austria and were forced to flee their country (where both were entertainment stars) and start over in the U.S. film industry.

Ludwig Stössel and Ilka Grüning had been born in Austria and were forced to flee their country (where both were entertainment stars) and start over in the U.S. film industry.FLASH FORWARD to 2024. Here we are today, 82 years after the production of Casablanca, right around the anniversary of the shooting of the airport sequence. It’s such a different world now with our cell phones, social media, self-involvement, and short attention spans. History is a lost art and many in the audience can’t begin to understand the purity of Victor Laszlo’s actions or how important Bogart’s small head nod was to the musicians. But in summer 1942 nobody knew if what was then called the “free world” would remain free, or if the Axis Powers would triumph. This is not an exaggeration. This is fact. The limits of German and Japanese power had not been ascertained in the summer of 1942. The United States was an untested power just gearing up and a year away from putting infantry boots on the ground of Europe.

IRL, Madeleine LeBeau meant every tear.

IRL, Madeleine LeBeau meant every tear.To me, Victor Laszlo actually gets the two best moments in the picture, first when he leads “La Marseillaise,” and later when he shakes Rick’s hand and says, “Welcome back to the fight. This time I know our side will win.” Victor might have known, but I assure you the 1942 audience didn’t. They could only hope, and it seemed a faint hope at that.

And this is why the “La Marseillaise” scene has such power even today. The underdogs, the oppressed refugees, rose to their feet and dared to drown out the all-powerful Germans. Most poignant of all, Madeleine LeBeau sings her heart out with tears streaming down her face because she knows that in another reality, she might just be locked away or dead and not making pictures in America.

Madeleine’s husband Marcel Dalio (center) portrayed Emil the croupier. IRL he and Madeleine had lived the “letters of transit” experience as they sat in Lisbon and awaited passage across the Atlantic.

Madeleine’s husband Marcel Dalio (center) portrayed Emil the croupier. IRL he and Madeleine had lived the “letters of transit” experience as they sat in Lisbon and awaited passage across the Atlantic.

March 10, 2024

Masters of Fear

Callum Turner portrayed the real flier John Egan and Austin Butler the real Buck Cleven.

Callum Turner portrayed the real flier John Egan and Austin Butler the real Buck Cleven.I admit to some skepticism going into the Spielberg/Hanks miniseries, Masters of the Air. It had been so long in production through the pandemic that I figured the delays meant conceptual trouble—and disappointment for the viewer. Episode 1 seemed to confirm my suspicions, as the characters didn’t grab me and the darkness of frame and mumbling of dialogue hinted at trouble ahead.

You see, here’s the thing: I wrote a book called Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe that saw me dive deep into the history of the air war over Europe. I became all about the Eighth Air Force and the heavies and “little friends,” with the help of fliers in their 80s and 90s who still lived life at 20,000 feet battling Germans in their dreams and nightmares. All had flown with Stewart and knew him as a damn good command pilot. My research included visiting bomber bases in the English countryside and taking rides in B-17s and B-24s because I knew if I got one thing wrong in this story, the WWII buffs would nail me for it, and so I triple-checked every detail before publication.

I grew fond of Barry Keoghan as Lt. Curt Biddick, only to see him die in an exploding B-17. Note the vividly realistic bomber base in the background.

I grew fond of Barry Keoghan as Lt. Curt Biddick, only to see him die in an exploding B-17. Note the vividly realistic bomber base in the background.When you get that close to a topic, it leaves an impression. I have since been driven to watch the best Hollywood picture about the air war, Twelve O’Clock High, made in 1949, over and over. The other one to watch was Memphis Belle, the 1991 feature that for the first time showed us not aging Hollywood character actors populating the cast and bomber crew but young men in the cockpit and young men manning the guns.

OK, bear with me. The average age for the pilot of an American heavy bomber in World War II was 22. Twenty-two. The pilot was the commander of the ship and in charge of the other nine living, breathing young men onboard. If the 22-year-old didn’t do his job right, those boys in the plane were dead. If he did do his job right, there was still a very good chance they were dead because these kids took to the air every day against many dangers, most prominent of them the German air force—the Luftwaffe.

I found it fascinating as I wrote Mission to learn about all they faced. Jim Stewart didn’t fly the glamorous B-17 depicted in Masters of the Air. He flew the B-17’s ugly stepsister, the B-24, which could carry more bombs but was prone to fuel leaks. In short, you could blow up because of leaking gas at any point on a mission. If you managed to get to altitude in the horrible English weather, always cloudy, always damp, and if you didn’t collide with another bomber in the crowded skies, you’d get to altitude and put on an oxygen mask as the temps dropped to 30 or 40 below zero Fahrenheit. One of Jim’s contemporaries, Lucky Luckadoo of the “Bloody Hundredth” bomber group, said just the other day that it was so cold at altitude in European winter that if you took off your gloves for even a minute, you risked your fingers “self-amputating.” They would break off in the cold.

Nate Mann played Rosie Rosenthal, a fearless pilot who flew 25 missions to earn his ticket home—and re-upped because the job of defeating Hitler wasn’t done. Note the lack of a grotesque, foot-long icicle on the oxygen mask at altitude, one of the concessions to telling a concise story.

Nate Mann played Rosie Rosenthal, a fearless pilot who flew 25 missions to earn his ticket home—and re-upped because the job of defeating Hitler wasn’t done. Note the lack of a grotesque, foot-long icicle on the oxygen mask at altitude, one of the concessions to telling a concise story.Now, back to Masters of the Air. For me, everything changed with episode 2, depicting the first mission of the 100th Bomb Group, which was one of the first units to take to the air to bomb continental Europe. They went up in a recently invented airplane, 10 men to a crew, and were slaughtered trying to bomb targets in various parts of Germany. Inhuman slaughter, yet these young guys kept going up, kept fighting Hitler, doing their part. And they kept getting shot down. It’s telling that the three WWII fliers who helped me write Mission all were shot down on missions to Germany. All three bailed out of a falling bomber on different missions and spent the latter part of the war in German prison camps.

Jim Stewart at left early in 1944 with the crew of the B-24 known as “Lady Shamrock.” Masters of the Air meticulously recreated the gear worn by each flier, which included a heated flying suit under shirt and pants, overalls, jacket, boots, gloves, a flak vest, headset, mae west, and parachute.

Jim Stewart at left early in 1944 with the crew of the B-24 known as “Lady Shamrock.” Masters of the Air meticulously recreated the gear worn by each flier, which included a heated flying suit under shirt and pants, overalls, jacket, boots, gloves, a flak vest, headset, mae west, and parachute.I’m finding that Masters of the Air tells a powerful story powerfully well. Sure, there are nits to pick, as with any historical miniseries, but to me, this is spellbinding stuff. All the characters depicted in the series are real; they lived and breathed—and many died—during World War II. It’s interesting to me that of all the perils depicted, the filmmakers didn’t or couldn’t take the time and expense to show the ice that formed around oxygen masks. So much ice that fliers would have to beat it off with their fists. But this bit of realism might, I guess, amount to a distraction as the film shows you how German fighters would zip by the planes and stitch them with machine gun fire as flak bursts detonated all about. These factors alone reveal what the guys in the planes went through. Young, young men fought that air war a year before the landings at Normandy. I dare to call them boys. Imagine for a moment that your own kid of 20 or 22 has to bear the responsibility of combat missions in a plane that a few years earlier had existed only on drawing boards. For a stretch, the fliers, these boys and young men, were the only Americans fighting in Europe, doing so as described—at 20,000 feet and 40 below.

Ncuti Gatwa played 2nd Lt. Robert Daniels of the 332nd Fighter Group, better known as the Red Tails and Tuskegee Air Men. Daniels was shot down in a mission over Marseilles and then a prisoner in Luft Stalag 3.

Ncuti Gatwa played 2nd Lt. Robert Daniels of the 332nd Fighter Group, better known as the Red Tails and Tuskegee Air Men. Daniels was shot down in a mission over Marseilles and then a prisoner in Luft Stalag 3.Masters of the Air manages to cover a lot of story threads, from the psychological toll of the missions to the grief of losing friends, from the fliers who bailed out and evaded capture with the help of the various resistance movements to those who ended up in German prison camps. In episode 8 we meet the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Squadron and I was glad to see them. Welcome to the war, boys! Welcome to this series, showing us what it was like for black fliers doing their part and facing a cold reception after they had been shot down and arrived at Luft Stalag 3. Sometimes you barely get to know characters before they die in battle, but guess what—that was their experience, too. You met a guy yesterday, and today he died in an exploding plane.

I’ll be sorry when Masters of the Air ends with episode 9. It has been an emotional experience for me as an author who listened to stories from the men who lived this part of the war; an author who tried to do those stories justice in Mission. How did any of these fliers master their fear to climb into those planes time and again, knowing the odds? They did it for freedom, for democracy—ideals that have become so fractured in our modern day. But Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks clearly understood these concepts when they took on the mission of giving us Masters of the Air, which provides a visceral look at what the men of the U.S. Army Air Forces endured on the long haul to victory in Europe.

********

On a different note, check out the fun exercise I was asked to complete at Shepherd.com regarding my latest book, Season of the Gods, the true story of how the screen classic Casablanca came to be.

January 10, 2024

Givin’ It All Away*

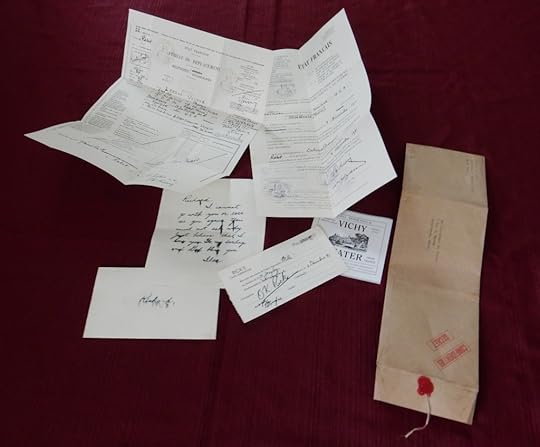

So you say you haven’t yet read Season of the Gods—the novel about how Casablanca came to be? Would it pique your interest if you learned that a major Hollywood production company is now attached to this story and enthusiastic about its possibilities as a feature motion picture? Would it poke you in the ribs if you learned of a sweepstakes underway on Red Carpet Crash that includes five finalist prize packs and one grand prize winner of a set of replica letters of transit and other key documents from Casablanca? I kid you not—the grand prize is the letters of transit (see photo above for a glimpse), and also Ilsa’s rain-smeared letter to Rick and other Casablanca papers.

The grand prize set of Casablanca documents.

The grand prize set of Casablanca documents.Here’s the finalist prize pack:

Signed copy of Season of the GodsCasablanca Blu-ray loaded with special featuresCasablanca t-shirtRick’s Café Americain matchbookSeason of the Gods bookmarkAnd the grand prize winner gets all that PLUS the set of replica Casablanca documents, including the letters of transit.

To enter, visit Red Carpet Crash today—the sweepstakes ends Friday, February 2.

Just as a quick reminder, Season of the Gods is 100 percent fact-based and tells the story of Irene Lee, Warner Bros. story editor (the only female executive in the company) who finds an orphan stage play and engineers its purchase by the studio’s executive producer, Hal Wallis. Irene’s a plucky one, five-foot-nothing and holding her own in misogynistic Hollywood. She serves as a de facto producer of Casablanca even though Hal Wallis won’t give Irene, a mere female, that title. She works with the crazy brother screenwriting team of Phil and Julie Epstein to craft the story and then with other writers brought in—Howard Koch and Casey Robinson. And she finds love along the way, or rather doubts she has found love when she considers her “junkyard of a love life.” I have such great fondness for the characters in the book, not only empathic Phil Epstein and his edgy brother Julie, but also Dooley Wilson, Hollywood novice in a white man’s world and dreaming of buying his wife a house; Claude Rains the easy-going roué; Conrad Veidt the elegant German expat eager to play Nazis and expose their evil; dark and cynical morphine addict Peter Lorre; gentle giant Sydney Greenstreet; Aaron Diamond, the New York carpet buyer who’s crazy about Irene; and Joy Page, Jack Warner’s stepdaughter who sees a role in Casablanca as a potential escape route from her difficult life at the Warner mansion, dubbed “1801” for its street address on Angelo Drive in Beverly Hills. And the backdrop. Oh, that backdrop. The dark months after Pearl Harbor when U.S. coastlines braced for invasion and defeat after defeat of Allied forces blasted across the headlines.

Plucky, little-documented Irene Lee, the real hero of Casablanca.

Plucky, little-documented Irene Lee, the real hero of Casablanca.I guess you can tell … I like this book. And I’m not alone. Season of the Gods has gotten some great ink, from Publishers Weekly BookLife (an Editor’s Pick), from Kirkus Reviews (which called it “EPIC”), and most recently from Annette Bochenek’s website, Hometowns to Hollywood. The Historical Novel Society interviewed me about the book, as did Grace Collins for her True Stories of Tinseltown podcast. I always felt that I wasn’t going to take the world of fiction by storm and that this would be a marathon; not a sprint. Fiction is a place bulging with seasoned talent and passionate readers who know what they want and what they like, and who am I but a nonfiction author daring to cross over with an idea that came from who knows where?

The fact that Hollywood likes the book is a potential game changer. No kidding, they signed me up as soon as they received and devoured the copies sent over. That said, this company-that-must-not-be-named now controls the film rights and it’s up them to announce the deal or not, and to make a movie or not. We shall see what we shall see, but all I can say to these great people is: Thank you for believing in this story.

To order Season of the Gods, visit Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or if you favor the independent booksellers (and want a discount), Bookshop.org.

As always, thank you for checking in. See you at the movies—the golden age movies, that is. And please let all your friends know about the sweepstakes!

__________

*Givin’ It All Away was the greatest song by a solid 1970s band called Bachman Turner Overdrive. When I typed this for the title, I thought OMG, remember that song? I’ve got to go listen to that song, which I hadn’t heard in ages. And, wow, what a blast from the past. “You took my heart/And you went away/We said goodbye/And we’re givin’ it all away.” Still a great song—all the fury of love gone wrong. (Just so you don’t think I’m a Johnny One Note who only writes about wartime Hollywood. Rock on, my friends.)

November 5, 2023

Playing It Safe

The first choice of Hal Wallis: Hazel Scott.

The first choice of Hal Wallis: Hazel Scott.I was watching Turner Classic Movies (U.S.) yesterday and heard Dave Karger’s introduction of Show Boat, MGM’s 1951 adaptation of a Broadway musical based on a 1926 bestselling novel by Edna Ferber. The plot of Show Boat concerns a traveling troupe of entertainers on the Mississippi River, one of whom is singer Julie LaVerne, part Caucasian and part Black. Karger explained that Lena Horne was originally penciled in as Julie because she had performed a number from Show Boat in the 1946 MGM musical, Till the Clouds Roll By. But MGM executives worried about putting a Black actress in such a pivotal role in a theatrical release and opted instead to cast Ava Gardner, all white, in the role. And at that moment I exclaimed to Dave Karger on the TV, “Why, those chickenshits!”

It’s difficult today to comprehend a United States in 1951 where Black people couldn’t be seen as equals in Hollywood productions. U.S. culture of the time still had white restrooms and “Colored” restrooms, white swimming pools and Colored swimming pools. It was the time of the Green Book and would stay that way for another generation!

But, to me, Louis B. Mayer and his MGM brethren were chickenshits because Hal Wallis, executive producer at Warner Bros., had already stormed this beach, had already claimed this ground, had already planted the flag of equal rights by daring to show a Black character as equal to white when Wallis had said “Screw it” and cast Dooley Wilson as Rick Blaine’s best friend in Casablanca a whopping nine years before Show Boat entered production.

Wallis then deferred to up-and-coming Lena Horne.

Wallis then deferred to up-and-coming Lena Horne.As detailed in Season of the Gods, Wallis and his team had bought the stage play “Everybody Comes to Rick’s,” which featured “Sam the Rabbit” as a key character, a flamboyant Black entertainer at Rick’s nightclub in Casablanca, French Morocco. Originally, Wallis’s inclination was to play up the flamboyant part by switching the Sam character to a Black female and his two choices for Sam were Hazel Scott, gorgeous multi-talented 20-year-old sensation then taking New York by storm, or the aforementioned Lena Horne, then beginning her career in Sunset Strip venues.

I’ll rely on you to read the debates in Season of the Gods and move on to the next plan, which was to cast Clarence Muse, dependable Colored stereotype, as Rick’s more-or-less second banana, this when early script drafts of Casablanca by Phil and Julie Epstein relied more on humor and less on romance. But Muse didn’t fit the evolving storyline, and Muse had been seen and seen and seen in this one type of role. Overseen. Wallis wanted more out of what was rapidly becoming a Very Important Picture as the world unraveled and Northern Africa hit the headlines. In the opinion of Hal Wallis, if young Black men were willing to go and die fighting the Axis powers in the name of freedom, then Black people could be seen as equals in Warner Bros. pictures.

Sam #3, the safe choice: character man Clarence Muse.

Sam #3, the safe choice: character man Clarence Muse.Cue more debates in Season of the Gods, as Wallis was warned he could “lose the South,” a critical market for box office returns, if he dared cast a Black man as equal to whites. Southern audience members could get up and walk out, demand their money back, and tell all their friends to stay away. This was the same American South that protested the working title of a George M. Cohan biopic then in production at Warner Bros., Yankee Doodle Dandy, because it dared to include the word “yankee” in the title! This, my friends, was the fucked up world of 1942: Americans were fighting racist authoritarianism overseas while ignoring their own racism at home.

Wallis saw it, and Wallis made a stand. He eschewed the stereotyped Clarence Muse and cast a well-worn, globetrotting entertainer named Dooley Wilson as Sam. I attempted to try to see the world of that time through Dooley’s eyes in the narrative of Season of the Gods and that in itself proved a surprising experience. Dooley just wanted to get by, so he looked away from the racism, figuratively and also literally, as he avoided eye contact with the people he met at Paramount and Warner Bros. But oh, the surprise in store for Dooley when he began production of Casablanca. You want me to WHAT? Underplay? He couldn’t believe it as his first couple of roles in Hollywood had been as a porter and a butler, doing the usual wide-eyed comic takes.

Casablanca holds up so well today because of the truth it presents. The people crammed into the lifeboat called Rick’s Café Americain—whether terrified Jews fleeing Hitler, a world-weary Black piano player, or a Czech freedom fighter and his wife—are just people trying to survive, trying to find peace. Wallis had gambled and won; his picture became everything envisioned and much, much more. I don’t know how many people walked out in the South, but that number was offset many times over by box office in New York and Chicago and Los Angeles. Casablanca scored big on release in 1943, then again in 1949 and 1956 reissues, then endured on television.

The real Sam: new-to-Hollywood Dooley Wilson.

The real Sam: new-to-Hollywood Dooley Wilson.Yes, Show Boat “played it safe” in 1951 by casting Ava Gardner in a leading role instead of Lena Horne. And yes, groundbreaking Warner Bros. (minus Hal Wallis, who had moved on) would also play it safe in 1957 when time came to cast for Band of Angels, an antebellum story set in Louisiana. In the role of half-Black heroine Amantha Starr, Warner Bros. cast Yvonne De Carlo instead of, say, Dorothy Dandridge in the part because the world wasn’t ready for Clark Gable to be kissing Dorothy Dandridge. What if they walked out in the South?! (I will acknowledge progress made by 1957 in casting Sidney Poitier in a key role.)

So, sure, the world has changed, and yet the world hasn’t changed. There’s still hate because of the color of your skin or your ethnic heritage or the god you worship. And there’s still a burning need for courage like that displayed by Hal Wallis, who dared to do the right thing back in 1942.

Season of the Gods: A Novel is now available from Amazon.com, Barnesandnoble.com, Bookshop.org, and other booksellers.