The Big ‘However’

It’s baffling to me to think that in my lifetime, there was a thing called segregation. In my lifetime! I wasn’t old enough to actually see a restroom or swimming pool for “colored people,” so when I’m reminded that even in the 1960s things were that way, I’m stunned. All of which points out to me the twentieth century trailblazers who wouldn’t settle for the two-tier system in America, such as Warner Bros. executive producer Hal Wallis. As detailed in my book Season of the Gods, Wallis despised studio boss Jack Warner, whose narcissism clashed with Wallis’s own fearsome ego. One of the things they clashed over was Black talent.

Hal Wallis (right) with Casablanca director Michael Curtiz and Ingrid Bergman.

Hal Wallis (right) with Casablanca director Michael Curtiz and Ingrid Bergman.Years ago, while combing the U.S.C. Warner Bros. Archives, I came across a summer 1941 Jack Warner memo indicating he wanted some “colored people” for comic relief in the Custer biopic then in development starring Errol Flynn. Warner was an advocate of comic turns in all the WB pictures—they called them “bits of business” back in the day—always done by white character actors like George Tobias or Alan Hale, or by Black actors like Clarence Muse. In the case of the Custer picture, the Jack Warner memo resulted in the appearance of a “boy” tending Custer’s hounds at the beginning of the picture, and new scenes for housekeeper “Callie” played by Hattie McDaniel, then not far past her Academy Award win for Gone With the Wind. McDaniel’s Oscar, richly deserved for a nuanced performance as Mammy, had sent shock waves through the continent—America wasn’t ready to recognize 1) a Black character as wiser or more grounded than the white characters in the piece, or 2) a Black performer as talented as Caucasian counterparts.

Hattie McDaniel with the teacup ‘bit of business’ in They Died with Their Boots On (1941).

Hattie McDaniel with the teacup ‘bit of business’ in They Died with Their Boots On (1941).I don’t know about you, but McDaniel’s bits of business in the Custer picture They Died with Their Boots On have made me uncomfortable for decades—the bit about the fortune telling with the teacup and rabbit’s foot and the thing in the garden with the owl. Yikes. But that was Jack Warner for you, always ready to beat people over the head with painful humor delivered in person through notoriously horrendous jokes or through his pictures of the 1930s and 40s, none of which I find funny. Whether it’s Boy Meets Girl or Arsenic and Old Lace, the humor is loud, desperate, and, to me at least, painful.

But back to the Hal Wallis–Jack Warner enmity. Wallis acquiesced to Warner in the case of Custer, but times were changing. At the turn of 1942, with America newly launched into world war, Wallis bought a stage play called “Everybody Comes to Rick’s” and jammed it into the production schedule, renaming it Casablanca. A key member of the cast was a gay “Negro” piano player called Sam the Rabbit, who was written as a stereotype of the times. However, in developing the characters and screenplay of Casablanca in February and March 1942, Wallis was seeing headlines like this one in Daily Variety: BETTER BREAKS FOR NEGROES IN HOLLYWOOD. Dated March 24, the article began, “Negroes are to be given an increasingly prominent part in pictures,” according to Walter White, head of the NAACP. White stated that “Darryl Zanuck and other production chiefs had promised a more honest portrayal of the Negro henceforth, using them not only as red-caps, porters and in other menial roles, but in all the parts they play in the nation’s everyday life.”

Dooley Wilson as Sam, Rick’s loyal BFF.

Dooley Wilson as Sam, Rick’s loyal BFF.Hal Wallis embraced this controversial new approach, reasoning that “Negroes” were fighting and dying for their country in the war, spilling the same color blood as white people, so why not treat them as equals in pictures? First up was the role of Parry played by Ernest Anderson in the Bette Davis sudser, In This Our Life (1942). Parry was the young son of a household cook (Hattie McDaniel again) who was wrongly accused of a fatal hit-and-run accident. He’s cleared by the end of the picture and off to law school—and throughout, his part isn’t played for laughs. At all. And with Casablanca, Wallis considered the same approach—taking the character seriously. Wallis considered writing Sam as a woman and casting either Hazel Scott or Lena Horne until studio story editor Irene Lee and writers the Epstein twins won Wallis over that Sam must be a male to head off any thought that Rick and his piano player might be romantically involved—which would sap the intensity of the Rick–Ilsa dynamic.

Over time, veteran Black character actor Clarence Muse was considered for the part of Sam, and Hollywood newcomer Dooley Wilson was chosen. All the while, Jack Warner played rooftop sniper and argued against letting Sam be played as Rick’s best friend and confidant because the picture might be banned in the American Deep South for showing a Black man as Rick’s equal. And Wallis kept pointing to the war effort and the changing times, stuck to his guns, and gave the world a character for the ages in Sam, a role and a performance that holds up 100 percent today, going on a century later. There isn’t one false note in Dooley Wilson’s characterization, not one cringeworthy moment of the kind that mar Hattie McDaniel’s performances—bits forced upon her to reassure white viewers they were indeed superior.

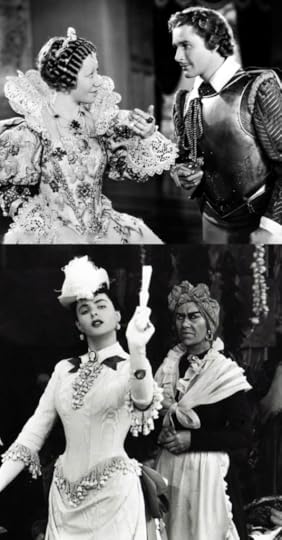

Flora Robson as Queen Elizabeth with Flynn in The Sea Hawk (1940); Robson as a Black slave with Ingrid Bergman in Saratoga Trunk (made in 1943; released in 1945).

Flora Robson as Queen Elizabeth with Flynn in The Sea Hawk (1940); Robson as a Black slave with Ingrid Bergman in Saratoga Trunk (made in 1943; released in 1945).Now we come to the big “However.” Just months after Casablanca wrapped, Wallis started work on a picture called Saratoga Trunk, from the novel by Edna Ferber. The lead role of Clio Dulaine in Saratoga Trunk was coveted, much as had been the part of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. I remember how badly Olivia de Havilland in particular wanted to play illegitimate, half-Black Clio returning from France to post-Civil War New Orleans to avenge her mother. But do you know who Hal Wallis chose for Clio in Saratoga Trunk? Fair-skinned Swede Ingrid Bergman, that’s who, her hair dyed black to “satisfy” the problem of race. And for the part of Clio’s Black maid Angelique, Wallis selected very white, British-born Flora Robson, who just three years earlier had portrayed Queen Elizabeth I in Flynn’s The Sea Hawk! For Saratoga Trunk she’s slathered in hideous dark-skinned makeup because, Wallis said, “the role was so large and important that it was beyond the range of many [Black] actresses of that time.” Um, OK, Hal. Sure. Ironically enough, Robson would be nominated for an Oscar for her take on Angelique, whereas today, viewers simply take one look at her, gasp, and go, “Wut up with the blackface?” So, sometimes Wallis challenged the norms and sometimes he didn’t; after all, Wallis straddled the line between artist and businessman. When he got it wrong, the result was Saratoga Trunk, a picture known only to die-hard cinephiles. When he got it right, the result was Casablanca with its many perfections, not the least of which is quiet, steadfast Sam, best friend of the white guy. (And I’ll bet you Rick’s Café Americain didn’t hold even one segregated restroom.)