Robert Matzen's Blog, page 13

July 10, 2016

Juicy 2: A Shot Across the Bow

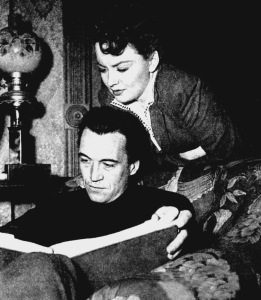

Olivia may seem to be at rest in this shot taken around the time of the Huston affair, but she never really was.

So where were we? Oh that’s right, in the middle of a love triangle between Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and John Huston. OdeH began it with Errol Flynn in 1941 after hot-blooded Frenchwoman Lili Damita had finally filed for divorce from in-like-Flynn. Livvie had told Errol point blank when he proposed to her in 1937 (big of him to propose while heavily married) that she wouldn’t do anything with him (think sex) while he was bound to Lili. Then nature took its course with Flynn and Damita over the next four years, leaving both Flynn and de Havilland at liberty during production of They Died with Their Boots On from July through September 1941. As much as Livvie would like you to believe that she and Errol didn’t do the horizontal tango, well, they were adults, beautiful, and known to be dating. She was going through a rough patch with her employer, Jack Warner, and Errol was an iconoclast and particularly supportive of her cause. Oh, and he had just seen completion of his bachelor pad up on Mulholland Drive, a place he had designed with pride as a sexual Mount Olympus. They were young, unattached co-workers who had been attracted to each other for years and now had their evenings free in a hideaway on top of a mountain. You do the math on that one.

Then something happened. Something bad. She found out something or he did something or she did something or she simply got too close and stared in the eye of the Flynn manbeast, but suddenly they were estranged at the beginning of 1942 as she began making her new picture with Bette Davis, In This Our Life. And then, as reported here last week, came the thunderbolt. Just after breaking up with Flynn she fell head over heels for John Huston and he for her. Well, no he didn’t. Huston was one of those bad boys you hear tell of. He loved ’em and left ’em, but by all accounts this guy could charm a gal right out of her panties and he did it all the time, right under the nose of his wife, Lesley. I’m telling you, John Huston, a not very handsome man with a nose that rambled all over his face, scored with the babes at all hours of the day. And who should be vulnerable rebound girl but OdeH when he began directing her in this new picture with Davis. (Note: As reported in Errol & Olivia, Livvie was a sucker for older authority figures, and Huston fit the bill to a T.)

John Huston went to war and distinguished himself as a combat journalist, but it was also convenient to get away and let things cool off on the home front.

Scandal ensued because Livvie and John were bangin’ here, there, and everywhere, but Huston being Huston, he began to get a little uncomfortable falling under the scrutiny of a serious, highly intelligent, kinda nuts, powerhouse human like de Havilland, who suddenly had the idea they were soon to be Mr. and Mrs. So what did he do? He joined the army and got as far away as he could think to go, to the Aleutian Islands past Alaska proper, where there were no telephones, to make a documentary about the war being fought up there between the Americans and the Japanese. “I’m sorry, baby, I can’t call for two months. There aren’t any phones.”

Olivia de Havilland was a stand-up woman in 1942, and remains one today, a titan among humans, smart, funny, multi-talented. Did you know she can imitate a dog’s bark so well that she can converse with other dogs? Did you know she can sketch like a pro? She used to entertain cast and crew alike with these sidelights while, oh by the way, making enduring classic motion pictures and earning Academy Award nominations and statues.

As things always went with Mr. Huston, this lover was traded in for the next lover. Livvie and John went their separate ways, and she got a nice tour of the fiery pits of hell pining away for John Huston while she was blackballed from the motion picture industry by Jack L. Warner and then almost died of viral pneumonia while entertaining the troops on Fiji Island in 1944. It was rough for Livvie, while Huston didn’t miss a beat.

Nora and Errol Flynn participate in the Victory ball not long after the memorable evening with John Huston.

CUT TO APRIL 29, 1945. There’s a party at the home of David and Irene Selznick, and Errol and wife Nora are invited, as is John Huston. Both Errol and John were three-fisted drinkers and half in the bag when they edged within earshot, and Flynn in his wisdom decided to fire a shot across Huston’s bow. Neither would ever dare repeat what he said at that critical moment, but the subject was whom-was-Livvie-with-and-when. I’m pulling my punches here, but Flynn didn’t when he stated it one drunk to another.

As reported in Errol & Olivia, Flynn’s shot-across-the-bow hit Huston right in the crotch, which is where John kept his ego. “That’s a lie,” he spat. “Even if it wasn’t a lie, only a sonofabitch would repeat it.”

I love Errol’s response. It’s so him: “Go fuck yourself.”

Bombed though they were, both knew not to wreck the home of David O. Selznick, so they took it outside to a gravel drive down at the bottom of Selznick’s garden, where two former real-life prizefighters practiced the sweet science on each other’s faces. Huston must have underestimated Flynn’s skill because with one straight left jab, Huston was down to his knees.

And here’s where we’ll leave the story until next time, when our little love triangle will reach its twelve-round conclusion.

Coming in October: Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, with more tales of real-life Hollywood in the golden age, when truth was stranger than fiction.

July 1, 2016

Juicy

While researching one of my books at the Academy Library in Beverly Hills, I came across a juicy letter, and I can’t even remember whose papers I was looking at. Logically speaking, it was a John Huston file because the letter was written from Olivia de Havilland to John Huston in January 1967. She opened by saying that she took her kids to the theater to kill time and the picture they walked into was The Bible, and she claims to have been shocked when she heard his voice narrating, and the voice took her back to another time and place, and she went on to describe intimate details about places they spent time together in 1942. I’ll quote the letter a little later, but first, some backstory.

Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland prepare for a scene on a darkened soundstage during production of They Died with Their Boots On at Warner Bros. In three months they would be estranged.

It was the wildest time in the life of a talented, no-nonsense survivor, the time she threw caution away and drove with the top down and no scarf. She was 25 and in a dark place, broken up not long from former boyfriend Jimmy Stewart (see Mission, coming soon), battling Jack Warner over her Warner Bros. contract and on again, off again romantically with long-time costar Errol Flynn. In January 1942 Errol and Olivia were off again because she had gotten too close to him around the time they completed They Died With Their Boots On and finally realized what a troubled soul he possessed. So that January she was a free agent and began production on a drama called In This Our Life with Bette Davis. The first day of work, kaboom, she fell under the spell of the picture’s director, who happened to be the hottest commodity in Hollywood at the time, 35-year-old writer-director (and notorious ladies’ man) John Huston. What Huston didn’t have in the classic looks department he more than made up for in charm, brains, and killer wit. Livvie, known as “Old Iron Pants” around the soundstages at Warners, found herself struck by the big thunderbolt like nothing ever before, not even with Flynn. Livvie was not only in love, she was in total, all-consuming lust, despite the fact that Huston was married at the time. High-profile Huston was involved in making a documentary on the war, Report from the Aleutians, and for a time they carried on from afar, but carry on they did through that year in what became filler for news columns, and a full-fledged scandal among gossip-mongers at Warner Bros.

John Huston doesn’t seem to be very happy with Olivia looming over him in this 1942 shot. They were seldom photographed together in what was supposed to be a secret relationship.

There was no way it would end well, and of course it didn’t. Serial-monogamist Huston grew bored pretty fast and moved on to Livvie’s Gone With the Wind co-star, Evelyn Keyes, while Livvie’s dark time went on. She would battle Warner Bros. for two more years, endure blackballing by all the studios, remain estranged from Flynn, battle her sister Joan Fontaine endlessly, and nearly die of illness contracted when she went off to entertain the troops in World War II. The clouds finally broke over Livvie’s head in 1946, and boy-howdy, what a dawn she witnessed. She won an Oscar for her 1946 picture To Each His Own, then topped that performance playing mentally disturbed Virginia in The Snake Pit in 1948, then won another Oscar in 1949 for The Heiress.

The thing to remember about Livvie is she has always been a loner. She has now spent a century as an island, a closed book, a tough cookie. To me, after having corresponded with this woman since 1978 and studying her life for my book, Errol & Olivia, this was the most revealing document I’d ever encountered. It read in part, “…I heard your voice. It was an extraordinary experience, for no one had told me that you had done the soundtrack, and, of course, with the first word I knew it was you speaking. It brought back, with a rush, the year of 1942 and the Aleutians, and the film you made there, that beautiful film, and ‘I’ve Got Sixpence,’ and your voice on the soundtrack for that picture, and, well, many things. I hope all goes well with you—I always have. I always will.”

Livvie is a beautiful writer, and here in a rare instance she bares her soul and engages in some flirting with a one-time lover who had meant the world to her, who had hurt her so deeply, and this was to say it’s all right. I forgive you and remember the good times. Classy move. Classy woman.

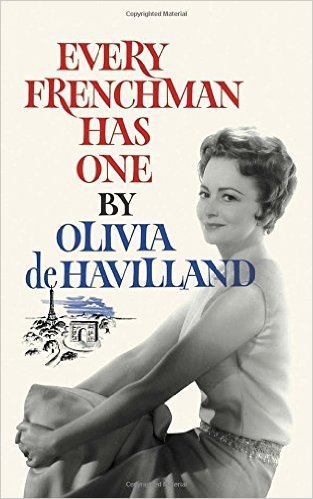

Happy 100th Birthday, Miss de Havilland. Speaking of your talent as a writer, I hope everyone goes right out and buys your terrific 1962 book, Every Frenchman Has One, which has just been re-released.

Next time we’ll look at one of the most incredible moments in Hollywood history, the time the aforementioned men in Livvie’s life fought over her, almost to the death.

June 20, 2016

Going All the Way

An interesting situation arose when I routed the manuscript for Mission for review to key subject matter experts who had helped in its development. Two are Hollywood historians, one is a WWII historian, and two are aviators who flew with Jim Stewart in the war. One of the fliers took umbrage with my depiction of Jim’s sexual exploits in pre-war Hollywood, and most stridently so. No spoilers here, not for a book still four months from release (and the embargo is still in effect), but suffice to say Jim was a far busier boy than you’d expect during his five-plus years in Hollywood prior to joining the military in 1941. The flier said, basically, that in his day you didn’t speak of such things, and he didn’t want Jim to be remembered that way.

I did some soul-searching after receiving this feedback because I greatly admire the man who delivered it, and I wondered if he was right that this type of information has no place in a book about Stewart’s military career. Here are the meanderings of my mind as I thought it through:

You’d never know it from the characters she played onscreen, but MGM contract star Ann Rutherford was another of the busy ones around town.

Sex wasn’t invented by the counter-culture of the 1960s. Sex was a favorite pastime of Hollywood citizens going back to the first days of hand-cranked cameras in the silent era. All roads in my research for Errol Flynn Slept Here, Errol & Olivia, and Fireball led to, well, sex. Errol Flynn was a big fan of indiscriminate sex. So was Clark Gable. Carole Lombard nurtured a healthy sexual appetite and did what came naturally and so did Jean Harlow. Even—dare I say it—Olivia de Havilland succumbed to pleasures of the flesh in an environment in which many of the world’s most beautiful, suddenly rich and famous people were crammed into a few square miles of exotic Southern California real estate, with no rules or chaperones. It became a matter of sport and ego to see who could bag whom, and Marlene Dietrich might be the prototype for sexual athletics as will be revealed in Mission when she looked at her lovers not as men or women or actors or people but as “conquests.”

If you’re a 30-year-old heterosexual guy and your day-job requires you to kiss Hedy Lamarr or Lana Turner—women whose every move is of interest to an entire movie-going world—what the heck are you going to be inclined to be thinking about but, My God this is a beautiful woman! If you’re a heterosexual woman known as a glamour queen and the script says today you will be romancing Flynn, Gable, or Doug Fairbanks Jr., and you’re looking into their eyes all day long, feeling their beating hearts, are you supposed to turn that off along with the soundstage lighting at 6 in the evening?

Olivia de Havilland tells a funny story about being in the clinches with Flynn shooting the love scene for Robin Hood over and over and “poor Errol had a problem with his tights.” You betcha. He was 28; she was 21. Nature was taking its course.

Why, Robin, I do believe you’re happy to see me.

There was a whole lot of nature going on in Hollywood by the 1930s when Jim Stewart reached his prime. Going into the Mission project I had heard that Stewart was known for having a “big stick” and I couldn’t even imagine it from this small-town product with a strong Presbyterian upbringing, but son of a gun, America’s boy next door had a side to him that reveals a lot about who he really was and what his psyche needed. “He had an ego, like all of them,” said a man who knew the older Jimmy Stewart well.

A picture started to emerge for me as I searched for the “real Jimmy Stewart,” not the lovable old guy on Johnny Carson, but the young one roaming Hollywood and then, seemingly inexplicably, running off with a big grin to join the Army nine months before shots were fired by Americans in what became WWII. And part of the story of who Stewart was, a significant part, involved his Hollywood love life, which meant that after all my soul searching, the juicy stuff stayed. I decided to go all the way … just like Jim.

Stewart once told his perturbed BFF Henry Fonda, “Hank, I don’t steal your dates. They steal me.”

June 7, 2016

20 Great de Havilland Moments

As we draw closer to July 1, which will mark Olivia de Havilland’s 100th full year on this planet, I started to think back to the most memorable moments of her screen career. She didn’t have the usual run of a Hollywood legend because she went to war with Warner Bros. and stayed off the screen for three years, and then faded from leading lady status in the 1950s, retrenching in Paris, where she has remained for 60 years.

As I detailed in Errol & Olivia, OdeH never rushed into anything in life, and turned down many scripts that became unmemorable pictures. But those she did make, she made well. I thought about doing the top 5, and then the top 10, but they kept coming so I finally decided to stop at 20, realizing that I’m missing many other great moments. I simply haven’t seen pictures like The Great Garrick, The Strawberry Blonde, The Dark Mirror, and My Cousin Rachel in recent times, so I’m depending on all of you to identify the considerable number of great scenes I must be missing. Yes I skew to Flynn-de Havilland just because I’ve seen them most of all.

Here they are, in reverse order, from 20 to down to 1, a list of memorable screen moments courtesy of OdeH—they just happen to include some of the most powerful scenes in motion picture history.

20. Government Girl—Smokey slithers across the floor of the crowded hotel lobby looking for a missing wedding ring, and Ed can’t miss her high-heeled legs under the sofa. Livvie wasn’t a comedic actress, but she does well in this crowded-hotel-lobby sequence, and also plays along to sell the sex. This little picture proved to be a surprise hit at the box office for struggling RKO.

19. Dodge City—On the staircase Abbie yells at Wade, “You can’t boss me!” and he stifles her protests with a surprise kiss and she makes a noise in her throat as if to convey, “Oh! This isn’t so bad!”

18. The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex—Penelope’s big brown eyes light up as if in neon every time she sees Robert Devereaux. This was her worst screen experience, a thankless role in a prestige picture courtesy of Jack Warner. She stood around a lot, but did what she could with the part.

Down yonder, there he is, Robert Devereaux, the Earl of Essex. Penelope rather fancies him.

17. The Adventures of Robin Hood—Sir Guy paws Marian’s jewel case and then rips it open to find the written warning for Robin. Awesome sexual tension between jilted Sir Guy and scheming Marian, revealing just a little of Basil Rathbone’s undisguised lust for Olivia de Havilland.

16. Light in the Piazza—After her daughter’s wedding to Italian innocent Fabrizio, Meg says to herself, “I did the right thing.” Even though the picture never made sense as presented, Livvie still owned those last moments and made them powerful.

Meg gushes with pride at the wedding of her daughter at the conclusion of Light in the Piazza.

15. The Snake Pit—Virginia stands in the common room at the sanitarium and her gentle, internal VO likens her surroundings to a snake pit. The camera changes focal length, lifting high above the soundstage until the illusion of all those crazy people is of snakes in a pit. And she remains fixed there, alone and vulnerable and, worst of all for her and for us, returning to sanity so she understands what’s going on.

Virginia stands in the middle of snakes in the pit in director Anatole Litvak’s beautiful, chilling shot.

14. They Died with Their Boots On—George scales the trellis to Libby’s balcony and proposes, and she swoons, and then it dawns on her what he just asked, and she scolds, “Oh, lieutenant!” and then a moment later, “Yes, general!”

13. Gone With the Wind—At the door chatting with Scarlett, Melanie spots Ashley coming up the road to Tara after the war.

12. Captain Blood—Snooty young Arabella decides to buy a pirate for personal use and he turns out to be a sassy, wrongly imprisoned English doctor. (Peter to Arabella, with a bow: “Your very humble slave, Miss Bishop.”)

11. Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte—Sweet Miriam stops the car and ever so slowly turns to Charlotte, revealing pure evil, and smacks her across the face repeatedly. Then she leans close and hisses, “Damn you. Now will you shut your mouth!” It was Livvie’s darkest moment onscreen in a picture seen as pure camp today, even though it received seven Academy Award nominations in 1965 and won three Oscars. Somewhere deep down it must have been fun to slap around Bette Davis after their long history together that includes contentious moments on the set of In This Our Life.

If Charlotte thinks she’s troubled now, just wait another minute.

10. Dodge City—At the newspaper office, Wade comes in to taunt Abbie after she takes a job there because a woman working for a living “Tisn’t dignified!” And during their byplay she hints that the natives object to his face. (Wade: “You should be home, doing needlework!”)

9. The Snake Pit—Virginia realizes she isn’t crazy anymore and doesn’t really love Dr. Kik. Then she connects with Hester in a brilliant crowning moment.

8. The Adventures of Robin Hood—Marian lets her hair down and begins to speak of love with Bess, and then Robin Hood barges in and he and Marian both proceed to let their hair down together.

Letting their hair down was a bear to shoot and took three tries with two directors.

7. Gone With the Wind—After Scarlett shoots the Yankee in the face, Melanie drawls, “I’m glad you killed him.” Then she strips off her nightgown to wrap the bloody dead Yankee in.

6. They Died with Their Boots On—Libby strolls onto the West Point green and engages Custer on guard duty, and they get into a big fight right off the bat. It was her first day of work on the picture, and she unleashed pent-up energy that Flynn matched for a terrific sequence.

5. The Heiress—Spinster Catherine finally locks the door on Morris and turns out the lights. She earned Oscar #2 here–she should have won it for The Snake Pit a year earlier.

4. The Adventures of Robin Hood—King Richard commands Robin to claim Marian as his bride; the king asks if she would like that and she beams, “More than anything in the world, sire.” Slam-bang ending to an epic picture. Livvie wasn’t crazy about playing a damsel in distress, but gave it her all anyway.

3. Gone With the Wind—Weakened Melanie forces herself up the long staircase at Tara to tend to Rhett after the death of Bonnie Blue Butler. Did this scene tip the Oscar to Hattie McDaniel? Both were flawless and completed the dramatic stair climb in an unbroken take.

A posed still can’t begin to capture the brilliance of de Havilland and McDaniel on that long walk up the staircase.

2. To Each His Own—Through the whole picture, old Miss Norris has been pinch-faced and bitter, but then the Army lieutenant realizes that she’s his mother and asks her to dance. It was the scene that sealed her first Oscar win, and if it doesn’t make you cry, you don’t have a pulse.

“I believe this is our dance, Mother.”

1. They Died with Their Boots On—George says goodbye to Libby, both sensing they’ll never see each other again. It was the best moment for both actors, and for director Raoul Walsh, and for the technicians who lit the set. Yikes.

If you want to destroy me no matter the mood or time of day, put this scene on. And BTW, however much you’re paying the lighting guy? It ain’t enough.

All right, lay it on me. What are some more great de Havilland moments?

For more on Olivia de Havilland and her upcoming 100th, check out Self-Styled Siren’s blog.

May 29, 2016

Thunderbolts

I would like to tell you all about my new book, Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, but I can’t tell you because there’s an embargo until August on coverage of it, including in my own blog. I can’t even tell you why I can’t tell you, because of the embargo. But I’d like to talk about a news item that woke me up at 6 yesterday morning: an old single-engine airplane crash-landed in the Hudson River next to New York City Friday evening, and the pilot drowned.

When I saw this story on the news, it riveted my attention because the instantly recognizable plane was a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, a plane as responsible as any other for winning World War II.

A formation of P-47 Thunderbolts in their heyday.

The P-47 is a main character in that which must not be named, a powerful, nimble single-seat fighter that could be fitted with bombs or rockets under its wings. Packs of these fighters, piloted by kids of 20, swooped above, below, and within the bomber stream of B-17s and B-24s that took off from England for bomb runs to Germany and France from 1943 through war’s end two years later. When I say kids, I mean kids who should have been pumping gas in filling stations or completing their sophomore year in college, but instead enlisted to become flyboys because there was no greater calling for this age group than to wear silver wings on your chest and enjoy every fringe benefit that went with being a fighter pilot. They fought for girls as much as for freedom, the freedom from Axis oppression and the freedom of being alone at 20,000 feet and commanding a 2,000-horsepower radial engine, with the devastating firepower of eight .50-caliber machine guns and wing-mounted rockets at your fingertips.

The German Luftwaffe didn’t like to see Thunderbolts coming. For ace German and American pilots going against each other, the Thunderbolt and the Bf-109 Messerschmidt or Fock-Wulfe 190 were evenly matched fighter planes in aerial combat, but as the war dragged on, the Luftwaffe ran out of aces and the Americans eventually ruled the skies in their Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs.

All of this flashed through my mind when I saw the news report yesterday morning, what a grand old bird had crashed in the Hudson, a distinguished veteran of service to our country piloted by a 56-year-expert pilot named Bill Gordon, an ace at acrobatics who took ships like this Thunderbolt, dubbed Jacky’s Revenge, across the country to thrill audiences at air shows and demonstrate what life was like in the fight for Europe. Engine failure brought Jacky’s Revenge down at about 7:30 Friday evening and even though photographs of the plane show Gordon did a tremendous job bringing her in with a kiss to the surface of the Hudson (nothing’s harder than a water landing), he couldn’t escape the cockpit and met his doom there.

Bill Gordon and Jacky’s Revenge.

On this Memorial Day, I’m saluting Bill Gordon, a guy with aviation in his blood who thrilled millions during his career by introducing the Thunderbolt and other World War II aircraft to new generations. And I’m saluting the Republic P-47 and the guys who flew her and lived and died in Europe and the Pacific during the darkest days of World War II. Their bravery and fearlessness bring tears to my eyes.

Note: For more on this topic, see the 1947 feature documentary Thunderbolt, with an introduction by Col. James Stewart, a man who appreciated this plane for saving his life many times over in combat over Germany.

A one-sheet for Thunderbolt, a Willie Wyler documentary about the ferocious flying machines that helped to win WWII. James Stewart provided a painfully short introduction.

May 6, 2016

Faces

I watched a Louise Brooks picture the other night, Diary of a Lost Girl, a 1929 German silent directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst. I’m not here to talk about Diary of a Lost Girl except to say, I didn’t get it. What happens happens slowly, and often without title screens, all in keeping with the New Objectivity of the time. As reflected in his pictures of the ’20s, G.W. Pabst’s world—Germany at the tail end of the Goldene Zwanziger, the Golden Twenties—was bleak and seedy, a socio-political vacuum that the National Socialists would soon be inhabiting. I’m sure many of you can give me a dozen reasons why Diary of a Lost Girl is good or great, but I can only speak for myself, and the slowly enveloping creepiness was a bit too much for me.

Louise Brooks in the late 1920s, sporting her distinctive and much-emulated hairstyle.

What held my attention was Louise Brooks. I sat mesmerized beginning to end looking at Louise Brooks in all manner of psychologically perilous situations. They called Helen of Troy “the face that launched a thousand ships,” and so Helen must have been Louise Brooks beautiful. If we were able to pull Louise Brooks off the spool of celluloid for Diary of a Lost Girl, she could be reinserted into any other filmstrip from any other time, and she would be just as arresting—and hopefully in better clothes.

I find all sorts of women to be beautiful for all sorts of reasons, outwardly and inwardly. You’re everywhere, you women, and I admire you all. And then there’s Louise Brooks. It does Brooks a disservice to say she’s sexy. She may be sexy in the traditional sense but it’s too symplistic term to be applied here. She grabs your attention when she appears and doesn’t let go. She’s got those big, dark, knowing, wide-set eyes and that severe dark hair framing her face and that wide mouth and flawless pale skin and wham, there’s nowhere else for your gaze to fall.

Louise never minded selling the sex angle.

Audrey Hepburn is another of those ship-launchers. There are a few out there who don’t get Audrey’s appeal. Maybe you’re one of them. As far as I’m concerned, Audrey could just stand there and not be a part of a plot or reciting lines or facing peril, just stand there, and I’d be watching that face with my mouth hanging open until she wasn’t there to look at anymore. I remember walking up a cobblestone street some months back in the ancient German town of Eppstein, this narrow little street with a few shops on it, and in one of the shop windows was an inexpensive little purse and my eye snagged on the purse because there was Audrey Hepburn’s face staring out from it. Time stood still. Five thousand miles from home, in Germany conducting research for a book on a dark 35-degree day in November, I didn’t know anything but, there’s Audrey. From one glimpse of that face applied to a commercial product.

Audrey Hepburn near the beginning of career, and toward the end of her life.

To my way of thinking, Audrey was as arresting near the end of her life as she was decades earlier in Roman Holiday, because, in her case, the beauty had deepened from all the living she had done and from decades of good deeds. There’s a sense of inner beauty from the face of a young Louise Brooks as well—she was by all accounts a smart, intuitive woman with a wicked sense of humor and strong independent streak.

My reading list is pretty long after finishing Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe (Coming Soon from GoodKnight Books—put it on your Christmas list now!) and among those titles is Lulu in Hollywood, a collection of the writings of Louise Brooks. I can’t imagine that this face was launched in Kansas, but that’s where she was born and raised. Supposedly she was molested as a child, which shaped her sexuality and, presumably, pointed her toward frank film performances, as well as a number of nude portrait sittings and many incendiary affairs. She made only a couple dozen films in a career spanning 13 years, in part because she snubbed her home studio, Paramount Pictures, just as sound arrived in 1929, the year of Diary of a Lost Girl. Among her credits was a picture with Carole Lombard, It Pays to Advertise, in 1931 with Carole on her way up and Louise sinking fast. Her last picture would be in 1938 and she’d be done in movies at age 32 and not rediscovered as a motion picture icon for another generation. How that face slipped from the mainstream for a while I’ll never understand.

Today the face of Louise Brooks has reemerged and collectors eagerly pay thousands for original still photos and movie posters featuring her, and I think it’s high time I added such a piece to my own collection and my wall. Productivity will suffer, because I’ll be staring with my mouth open quite a lot, but I can live with that if you can.

Bangs or no bangs, it all worked for Louise Brooks.

April 27, 2016

Dream Lovers

A toast to the lovers, Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier.

Raise your hand if you know what “pre-Code” means. Did you get a little hormonal surge reading that term? If so then you really know pre-Code and all it implies and promises.

In the late 1920s, when sound came into motion pictures, the Hollywood studios began feeling their oats and things got very naughty very fast. All of a sudden, hookers, drug addicts, gangsters, murderers, cheating husbands and wives, and—egads—gay people started showing up in movies, and things got so supercharged that the morally righteous enforced a Motion Picture Code beginning in 1934 and heavily censored movies thereafter. Heavily, heavily censored them. But for an all-too-brief five years, movies were heaven—or hell, depending on your point of view.

Personally, I think it was the be-all and end-all time of the Golden Age, and I can only imagine the result if the Code hadn’t come in to tame your vintage libertines like Harlow, Lombard, Rogers, and then Lana and Rita—not to mention Gable, Cagney, and Flynn. Alas, we’ll never know.

The other day I watched a 1929 musical called The Love Parade that had a strange effect on my red blood. It’s a dreamlike operetta about a rakish French nobleman, Count Renard, assigned to the court of Queen Louise of Sylvania, a verging-on-spinsterhood proper young lady who, upon introduction to Count Renard and the reading of a report about his scandalous reputation back home in France, tries to surrender her virginity as quickly as possible.

They’re married before the end of the first reel and then things get predictably complicated when the proud and still naughty Frenchman grows restless as, basically, the do-less “first husband” of the land. A happy ending can only be achieved after the count has asserted his authority and the queen has given herself freely into submission to her man. The basic theme here: bad boys are the way to go!

First impressions, lasting impressions for Queen Louise.

Even though this thing was made 87 years ago in fading black and white; even though they hadn’t really figured out sound recording yet and one sentence is over-modulated and the next is muffled, I think this picture is incendiary.

1930’s publicity photo

Jeanette MacDonald was 26 when she made her motion picture debut here after finding fame on Broadway. I can’t say I know much about early Jeanette pictures, and I hope my learned readership can enlighten me. Was she always this sexy before the Code came in? I heard myself say aloud, “She’s HOT!” while watching The Love Parade, and Mary said in her most doubtful voice, “Really?” Yes, really. Later on Jeanette would be teamed with Nelson Eddy, and together they’d take their operatic voices on an odyssey through many successful MGM musicals, all of them fine for family viewing, so this earlier incarnation of vine-ripening Ms. MacDonald was, to me, a pleasant surprise.

Maurice Chevalier was 15 years Jeanette’s senior and making his second American picture with The Love Parade. These two Paramount Players enjoyed chemistry together that would propel them into more pictures as a love team. From a distance, The Smiling Lieutenant, Love Me Tonight, One Night with You, and The Merry Widow seem to have been cut from the same bolt of cloth as The Love Parade—is that right? I’m pleading ignorance here because I’ve avoided early musicals studiously over the years and only knew Chevalier as the farcical grandfather guy from pictures of the 1960s. And the one the Marx Bros. tried to imitate in Monkey Business.

I also had no idea Chevalier was wounded in World War I and a POW for two years. Having some grasp of how the Germans felt about the French, I can’t imagine life in a prison camp from 1914 to 1916 was much in the way of fun, and maybe this gave Chevalier the joie de vivre that marked his screen persona—after you’ve seen hell, everything that followed had to be gravy, especially romping through a land of make-believe with Jeanette MacDonald.

Broadway entertainer Lillian Roth, then 19, took on the role of a maid in The Love Parade and spent her time as comic relief observing the torrid goings-on between the queen and count. I’ve got a glamor shot of Lillian on my wall that serves as testimony to my affection for the pre-I’ll Cry Tomorrow Roth, this being her memoir of addiction and recovery. Here she is at 47 interviewed by Mike Wallace about her life, saying at one point, “I’ve never felt … quite … adequate.” She describes a lifetime of not believing she was good enough, pretty enough, or talented enough (thanks to an abusive, perfectionistic stage mother)—all of which led Lillian Roth to the bottle for solace.

Lillian Roth shows some leg on a Paramount soundstage. At 19 she was more emotionally fragile than director Lubitsch realized.

The great Ernst Lubitsch directed The Love Parade, his first talking picture in a fantastic career that included crossing paths with two of my own biographical subjects, Carole Lombard (chronicled in Fireball) in To Be or Not to Be and James Stewart (covered in Mission) in The Shop Around the Corner. Lubitsch really did have quite the touch, a way of finding flesh-and-blood humanity, romance, and yes, deep sexuality in each and every picture. As detailed in Fireball, Gable referred to Lubitsch as “the horny Hun” and warned Mrs. Gable to stay away—you can imagine what sharp-tongued Lombard said to her husband in response. In I’ll Cry Tomorrow, Lillian Roth describes how the canny Lubitsch plucked her from the stage for Hollywood stardom in his first talkie with Chevalier, which led Lillian to assume she’d be the Frenchman’s love interest. But all along Lubitsch intended Roth and diminutive physical comedian Lupino Lane to play absurd counterpoint to MacDonald and Chevalier, and Lubitsch held fast to his vision even against Lillian’s tears and protests. The pain of this ego blow and its effect on her subsequent career comes through in the I’ll Cry Tomorrow narrative and served as one more factor in her descent into addiction.

The Love Parade was nominated for six Academy Awards, including an unlikely nod to the smug and self-satisfied Chevalier. Whatever, just watch and listen as Jeanette sings the haunting Dream Lover in that operatic voice and try to get it out of your head afterward. For good measure, here’s the instrumental waltz version. It’s a dreamy song for a picture about dreamy lovers.

Pardon me while I go panning for more pre-Code Hollywood gold. I’ve seen all the usual pre-Codes, but never thought to look under rocks labeled musical-comedy, where I shouted Eureka! upon discovery of The Love Parade.

MacDonald and Chevalier, reunited in another Lubitsch production in 1932, and still smoldering.

April 17, 2016

When Swords Flew

In a key lobby card from the set, Robin Hood stares down Sir Guy of Gisbourne in the middle of a duel for the ages.

I was prompted to think about the duel scene in The Adventures of Robin Hood by an email Tom Hodgins sent just this morning. In it he says:

“…years ago I mentioned on your Errol and Olivia blog that there is a moment in the Robin Hood duel where a sword fumble by Rathbone can still be seen in the film. Ralph Dawson edited it so beautifully that the eye can’t really catch anything, but, by pausing and freeze framing the image you can clearly see it. The only reason I made this discovery is because one day I thought I saw a slight blur on the film at that point, so I stopped my DVD to check it out. Voila—a boner by Basil that’s been on the film since its release without anyone having noticed it. (At least, I’ve never heard of anyone else having written about it). I’m sending you a couple of snapshots of the fumble taken on my computer off the DVD, just in case you never saw it for yourself. Basil, I’m sure, would not be pleased.”

I remember Tom mentioning this but never did think to follow up until the new prompting this morning. With Flynn lying under the candelabra, Rathbone says, “Do you know any prayers, my friend?” and Flynn responds, “I’ll say one for you!” and his next swing with the sword, as he’s lying flat on his back, is so ferocious that it catches Rathbone unaware and knocks the blade from his hand. It’s not supposed to, but that thing goes flying—which I didn’t notice in nine theatrical viewings of the picture and dozens more on the small screen. It’s only a few frames, literally like a quarter of a second, but it’s there with the sword tumbling high in the air end over end.

In Tom’s freeze frame, Rathbone’s sword has been knocked from his hand by an over-eager Flynn and is tumbling in the air–something NOT choreographed as part of the action. As can be seen, candles did not fare well in this encounter.

In general it proves how difficult the swordfights were to choreograph and how long it took and how exhausting for the actors, director, DP, and crew. Rudy Behlmer used some of the Rathbone color home movies to lead us through an examination of the filming of this duel scene in the bonus feature, Welcome to Sherwood, included as bonus material in the Robin Hood deluxe DVD package released years back.

We have all seen some fantastic cinematic duels, and for me this one is near the top of the list, with its terrific flow as the duelists fight their way out of frame to hack and slash in shadow and then re-emerge into view, still going at it furiously. They’re not fighting with foils but with heavy swords, their occasional, resonant clanking serving as reminders that these weapons are lethal.

As per another lobby card from the original set, the duel begins in the Great Hall.

In The Mark of Zorro there’s a fantastic moment when Esteban (Rathbone again) demonstrates his prowess with a blade to Zorro (Ty Power) by deftly slicing off a candle with a flick of his wrist. Then Zorro does the same and seems to miss because the candle is still sitting in place, but then he reaches out and lifts the sliced top off the remaining bottom and smiles innocently. Well, there’s no such gentlemanly foreplay in Robin Hood—when those big candles get hacked by the swinging swords, wax flies in all directions. In general, candles take a lot of abuse in the Robin Hood duel; not only are they hacked up by both combatants, but candelabras are tipped over and a candle is hurled as a missile by Robin at one point.

Wasn’t Basil Rathbone something? When the duel scene was shot, he was 45 years of age (17 years older than Flynn) and a heavy smoker, yet easily up to the rigors of shooting that scene. Two years later at 47 he nearly topped it in The Mark of Zorro. There’s a moment at the end of the Robin Hood duel that makes me frightened in retrospect for the safety of Mr. Rathbone and others in the cast, and that occurs after Sir Guy has been defeated and Robin hurries to the dungeon where he knocks the hand of the jailor holding the keys to Marian’s cell so hard that he bends his blade. He doesn’t bend it a little; he bends it a lot, demonstrating—what are we—78 years later how explosive Flynn was as a physical presence in his action pictures, and how wary stars and bit players alike would have been at the moment the director called, “Action!” and the film started to move in the magazine. That was when the money was spent, and when Errol would have been ready to make it look good, come what may for the other guy—as when he used muscle on the shot that Tom Hodgins pointed out, and Rathbone’s sword went flying. I know I’ve mentioned how Christopher Lee used to boast that Flynn nearly took off a finger shooting a duel scene during production of an episode of The Errol Flynn Theater, “and I have the scar to prove it,” Lee sniffed in an on-camera interview.

Basil Rathbone fights Tyrone Power in The Mark of Zorro. This duel was just as furious and just as lethal an encounter, but confined to a much smaller space. In both, Rathbone displayed fine fencing form.

I’m tempted to say that Flynn just didn’t have self-discipline in any regard except maybe for tennis. Archival film footage shows he was an awfully good tennis player and, as any weekend hacker knows, tennis is all about discipline. And when you watch the Robin Hood duel scene and the extra footage as described by Rudy Behlmer, you see that the swordfights were meticulously shot over a course of days and through all those movements with exposed sword tips, Flynn must have had discipline there too or Rathbone and so many others would be dead or blinded for life. But they lived to act on, so Errol must have been doing something right. You can cite for me all the instances where Fred and Al Cavens were doubling for Errol and Basil but there’s still a heck of a lot of Flynn-Rathbone footage visible in the Robin Hood duel, so these two must be given the credit they deserve for making it look lethal from beginning to end.

Thanks to the vision of Mike Curtiz, the combatants duel in shadow for a time, only to reemerge in frame still fighting with fury.

The near-impossibility of shooting this duel scene is demonstrated when, in the middle of the duel, Robin moves aside and Sir Guy flies past him and off the winding stone stairway. Sir Guy’s sword flies far off as dictated by physics and lands a good 25 or 30 feet away, but in the next shot, it’s magically laying on the floor under Robin’s feet so he can kick it back to Sir Guy in an admirable display of sportsmanship. So, let’s think about that moment on Stage 1 (or wherever it was) in January 1938 after Curtiz called “Cut” and they assessed what had just been captured on film. There must have been 40 people who saw the sword go to a spot where it would be impossible to retrieve unless Robin spent 15 seconds walking down the stairs, picking up the sword, and returning it to Sir Guy after he had collected himself up off the floor and dusted himself off. Talk about sapping dramatic tension! So what was that moment like, and what led to the decision to cheat through it the way they did? Was the stunt man doubling Rathbone the key player? Did he say, “If I have to do that fall again, it’s going to cost you another $500,” which prompted Mike to decide that yes the sword flew off but print it anyway and we’ll cheat. Was it a safety thing where the stunt man said, if I’m falling this way, then I’m making sure the sword goes that way so I don’t impale myself. Actually, that’s more likely and could explain why there isn’t a memo to or from Hal Wallis about this situation—it was a safety thing and you either X the fall out of the script in red pencil, or you cheat. All of which speaks to the incredible challenge of staging a fight like this.

The iconic promotion still. A few seconds after telling Robin Hood, “You’ve come to Nottingham once too often, my friend,” he will lunge and go head-first off the steps. His sword will fly far off camera.

I will never forget standing in front of the edit booths under Jack Warner’s window on the Warner lot, thinking about all that used to go on in those rooms, all the sweat and missed meals and midnight oil burning brightly as deadlines neared. Can you imagine the pressure of cutting film by hand on 1937 equipment when the final still needed to be processed and prints run in whatever, 36 or even 24 hours? I’ve never counted the individual shots in the Robin Hood duel scene but each one had to be spliced into a continuous flow in the work print—down to the right frame. There was no iMovie or Avid or Premiere Pro back then; there were just a lot of men and women working themselves into an early grave slicing film stock on crude machines under the scrutiny of bosses like Hal Wallis and Mike Curtiz. All I can say when I think about those poor people is, yikes. Oh, and, they’re not paying you enough.

So that’s what came to mind this morning when I saw Tom’s two frames from the DVD of The Adventures of Robin Hood. I’m probably not the only one who missed this remnant of a flub and I smile thinking about Ralph Dawson in his little room in the dark in Burbank thinking about how to make the frames work with what came next. In the foreground is Flynn squirming out from under the candelabra, which is critical to show, and in the background the sword is flying when it’s not supposed to be. But Dawson made the right decision, because the classic remains a classic, and it took the eagle eyes of Tom Hodgins and the luxury of frame-by-frame DVD stop motion to spot the goof.

April 12, 2016

Requiem for a Saint

I have a little more time on my hands now that Mission is off to galleys. Time enough to think, and it’s only occurring to me now after all these years how badly I wanted to be the Saint. The Saint, as in Simon Templar (initials ST, Saint, get it?), square-shouldered, impeccably dressed playboy adventurer who drove around England righting wrongs. He had no past to speak of, no hometown or parents or ex-wife. His ex-girlfriends only showed up when the plot dictated, and they were usually ne’er-do-wells who had stolen money or diamonds and fled some country or other leaving Simon behind, and now they were in trouble and needed his help.

The Saint’s calling card struck fear in the hearts of the bad guys.

Since I write for more of a movie audience than a pop culture audience, I mention the Saint and you think George Sanders and that’s fine. George Sanders made a terrific everything, including an entertaining feature-picture Saint, but George was hampered by the constraints of RKO production in the 1940s, and so his Saint was what he was, a formula programmer guy operating under the Production Code.

I always wanted to be the Swinging ’60s Roger Moore Saint from the British-produced ITC series. I’ll grant you that Roger Moore made a mediocre James Bond. He was little more than a placeholder as Bond, and many would say he was no George Lazenby let alone a Sean Connery. I guess I could sit here and count the reasons why he didn’t work as Bond, and they’re the same reasons he did work as the Saint.

Despite the bon mots tossed off by Connery’s Bond (“She’s just dead” … “I guess he got the point” … “Shocking”), there was gravity behind every movement, gesture, punch, and gunshot. Connery was a thinking-man’s Bond with the fate of the free world in his hands. Moore was the playful Bond, a big kid in a global candy store, reflecting Roger Moore’s off-screen mischievous self, a force that could never be contained. I remember Bond producer Cubby Broccoli at one point decades ago commenting on “those damned eyebrows” of Roger Moore, eyebrows that would shoot up out of nowhere and puncture otherwise dramatic moments in the Bond pictures. The basic question is, how can someone who’s “licensed to kill” have all that mirth inside him? Roger Moore as James Bond just came off as M’s bad hiring decision.

But as Simon Templar, Roger Moore was unbound. In an early Saint book, author Leslie Charteris described ST this way: “The Saint always looked so respectable that he could at any time have walked into an ecclesiastical conference without even being asked for his ticket. His shirtfront was of a pure and beautiful white that should have argued a beautiful soul. His tuxedo, even under the poor illumination of a street lamp, was cut with such a dazzling perfection, and worn moreover with such a staggering elegance, that no tailor with a pride in his profession could have gazed unmoved upon such stupendous apotheosis of his art.”

When Simon gives the halo a glance, it’s time for the opening credits.

Thirty-plus years after Charteris wrote that description, Roger Moore brought the Saint to life on TV in just such sartorial fashion, a smirking, self-satisfied force of nature, light hearted but deadly when he needed to be. He would drive up in his little white sports car to serve as a dashing instrument of justice that in mere moments from the beginning of each episode would come between evildoers and those they had oppressed. He brought his looks, wits, brains, style, and athleticism to bear on any situation and without the need for licenses, possessing an ambiguous morality that made him capable of straying outside the law as needed. The prologue would always culminate with someone growling something to the effect that “the infamous Simon Templar” had just arrived, and he would look up at the halo that suddenly appeared over his head, which would cue the theme music. In fact, and particularly in the early years (the show ran 1962–69), Moore wouldn’t just bump into the fourth wall but he’d rip it down, addressing camera about where he was and what was going on around him with such easy charm that you just bought it. If you want to see me truly happy, just put on an episode of The Saint and leave the room. I’ll be babysat for the next 55 minutes.

Years before Moore’s Bond had secretarial byplay with Lois Maxwell’s Moneypenny, they worked together on The Saint. (As a 10-year-old boy I was gonzo for Moneypenny. I’d sit in the theater screaming in my own brain, “OH MY GOD, HOW CAN YOU RESIST HER??”)

Moore was 35 years old when he began his run as the Saint; Roger was ex-military and an ex-clothes model who had been signed to a contract by MGM toward the end of the studio era. He never made any claim to being Olivier; he didn’t have a lot of range, but as Simon Templar he didn’t need it. He was charming and unafraid to take chances in front of the camera. He was also the perfect age to play the Saint from the beginning of the run to the end, finishing at age 42. By the time he shot his first Bond in 1973 he was already 46, and seven pictures later when he ended his run as 007, he was 58 and looked older than that and not very interested in what was going on. And by then, thanks to the aforementioned Broccoli, the human James Bond facing human crises had long ago been replaced by special effects James Bond with gadgets and explosions and existence in a world where gravity didn’t apply. All the while Moore kept aging and the Bond girls kept being 20 or 25 and it got kind of weird—that Gary Cooper-Audrey Hepburn kind of weird. Or Humphrey Bogart-Audrey Hepburn weird. At some point, for Roger Moore, it all stopped working.

Another Bond girl to come the Saint’s way–Goldfinger victim Shirley Eaton.

After another successful book or two, you know where you’ll find me, in a tux driving around London in my white sports car righting wrongs, or on the Riviera playing baccarat with a brunette on each arm and a halo over my head, talking to the camera, knocking out bad guys, stealing from the evil rich, keeping what I need, and giving what’s left to the oppressed poor, just the way Leslie Charteris wrote it all those years ago.

Or, at the very least, they’ll drape a shawl around my shoulders and plunk me in front of the TV to watch Roger do it, taking comfort in the knowledge that I won’t be likely to wander away from the facility and into the woods to be found face-down in some ditch. At least not for the next 55 minutes.

The one, the only Roger Moore as a smirking Saint, dressed to the nines (I could never keep the bow tie on a tux straight) and out to destroy that irritating fourth wall.

April 3, 2016

Brute Men

The gate to the corral is open, and I’m free! Free, I tell you! I’ve let everyone and everything go to concentrate on the book (to my understanding friends I say, thank you) and now finally it’s gone and I can begin to live my life again.

Last night I was ready for bed and watching House of Horrors on Me-TV’s Svengoolie. I’ve spent my life catching glimpses of Rondo Hatton but never really thinking about Rondo Hatton until last night, thanks to Sven’s thoughtful summation of Rondo’s life and times. You know, I have to applaud Rich Koz, the brilliant one behind the brutish makeup of Svengoolie, because it’s clear Rich is one of us, with a deep passion for classic Hollywood that is bound to go way over the heads of some in his audience, as when he details the life of a Virginia Christine or a Robert Lowery.

OK, so let me back up yet another step. In the 1930s Universal studios made classic monster pictures like Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mummy, and The Wolf Man. These characters became cash cows and were recycled through the years of World War II until they became pretty terrible B-picture derivatives made on limited budgets, with few original ideas coming along. But House of Horrors, released in 1946 at the tail end of the Universal Horror cycle, was pretty good with its story of an impoverished sculptor, played by Martin Kosleck, who is about to drown himself in the river when instead he pulls a brutish man out of the water and nurses him back to health. Rondo Hatton is that rescued brute, who in his gratitude begins to murder art critics who had disparaged the sculptor’s work.

Rondo Hatton in high school.

I connected with Rondo last night like I never had before. In very few words he conveys gentle intelligence that goes against the grain of those looks. Hatton was born in 1894 to educated parents and grew up in Tampa, Florida. He was quite the dashing figure as a teen and joined the U.S. Army, serving in Mexico against Pancho Villa in 1916 and then in the Great War. It was here his health began to suffer due to a pituitary condition called acromegaly that causes an overproduction of hormones, with the result being deformity in soft tissue. Sven postulated that German mustard gas had triggered the condition, which may be borne out by the fact that Hatton was discharged from the Army for illness before his tour of duty was completed. In other words, whatever happened, happened pretty fast.

Hatton became a newspaper reporter for the Tampa Tribune, where his ever-more-unusual looks were noticed by director Henry King during production of Hell Harbor on location in Tampa. King gave Hatton a small part in the picture. By the later 1930s Hatton’s Acromegaly had progressed to grotesque deformity that made him a natural for more motion picture work, so off to Hollywood he went, landing bit parts as a bodyguard or henchman or pirate—wherever a rogue’s gallery was being presented. The more old movies you see, the more you go, “There’s Rondo Hatton.” You see him so often he just blends right in with the fabric of classic Hollywood.

Well, who doesn’t appear scary with the flashlight-up-the-face look? I like this pic for the Mona Lisa smile and a hint of, “It’s a living.” His acting style in both “House of Horrors” and “The Brute Man” make me want to sit down and have a drink with this Hollywood veteran. If only.

Finally, in 1944 he landed at the most natural place in the world, Universal Pictures, which saw him as a “monster without makeup” and cast him as the featured killer in its Sherlock Holmes picture, The Pearl of Death, starring Basil Rathbone. After that Rondo was on his way, with nice billing in pictures

Svengoolie, aka Rich Koz, an appropriate name since he works so hard, furthering the cause of classic Hollywood.

including Jungle Captive, The Spider Woman Strikes Back, and then House of Horrors, where I rediscovered him last night. Here was Rondo at age 51 and in the last few months of his life. He would die of a heart attack resulting from his condition on February 2, 1946, six weeks prior to the film’s release. Another similar picture and his last, The Brute Man, would be released that October.

I just wanted to pause a moment to appreciate Rondo Hatton for making the most of his life and earning a spot in the Hollywood pantheon. He was given some nasty lemons at an early age, and made some terrific lemonade; we should all do so well. Appreciation also goes to Rich Koz for his ongoing gift to the world: hours of enjoyment while bearing the torch for classic chillers on Svengoolie.