Jacob Robinson's Blog, page 15

September 12, 2022

Read, Think, Make, Share, Monetize

For the past few years, all of my working schedule has revolved around five activities. In this post, I’ll go over these concepts — read, think, make, share, and monetize — and explain why I think they’re vital for any entrepreneur’s success.

ReadIt may be beneficial to know that the process I’m about to explain works a lot like an infinite step-by-step process. For example, you start with Read, then move to Think, all the way until you get to Monetize, then start back at Read and do it all over again.

Read is pretty self-explanatory. I read a lot — primarily both books and articles — to know things I probably wouldn’t have been able to figure out otherwise. I’ve already explained my book reading process in a previous post, but for articles I’m mostly looking for either 1) pieces that talk about current trends, or 2) stories/profiles that I might be able to gleam something out of. I never read current events (aka news) because most of the news cycle is useless information and if it was really that important it usually gets to my ears naturally, no newsfeed required.

I say “read”, though for my creative work in particular this is not exactly the case. Reading is definitely the best for knowledge related to keeping the business running, but for story or character ideas I can gleam stuff from art, movies, videogames, music, even just day-to-day walking outside and observing. For example, Sorry, We’re Closed is based on a single Twitter thread I saw about a person’s father committing suicide. It was totally by chance — I have no idea who the person was, nor will I likely ever encounter him again. That is the power of spontaneity.

ThinkThe natural next step after reading, at least in my opinion, is thinking. I take all the info I get from books, articles, games, conversations, etc. And try to make patterns out of it. What do I think is cool? What do I think is an opportunity? How can I use a trend to my advantage? All that sort of stuff. Every morning I get out a planning notebook and write whatever strategy stuff is in my mind. Sometimes this goes nowhere, sometimes the bits and pieces get reused somewhere else, and sometimes — just sometimes — it gets made.

MakeMaking is the most time-consuming process. I am very selective with what I make because of it. Sometimes I get too excited about an idea, plan the whole thing out in a weekend, and on Monday realize it’s a waste to work on because I have X, Y, and Z to finish first. I try to avoid this, but even now it happens.

I usually try to make MVPs, whenever possible. This is particular important I think for a solo creator as it allows me to work on a bunch of stuff at once without it feeling like a drain or splitting up my attention. As I come back to things, I add a little more, and a little more, and a little more… and as I build, traction usually comes with it. If no traction comes, it gets canned, and another project takes its place.

ShareIf a post-tree is made in a blog-forest, and no sharing is around, will a reader ever read it? I would argue not. I used to be very bad with sharing because 1) I was anxious that people were going to say it was bad, and 2) I didn’t know the right forms of sharing to fit my persona. For number one, I just snapped out of it — people still say it’s bad, but at this point I’ve been doing it for five years and don’t really give a shit. Number two is a little more of a complex case.

Let me give you an example. Gurus tell you to “use social media actively” if you want hits. They told me to use Instagram. What am I gonna use Instagram for? I thought. I never make pictures. I live in a boring desert. What am I gonna do?

Well, first thing I did was turn my Instagram into an art curation platform. I had a lot of art saved that I really liked, and I could use my Instagram actively with it, so I decided to share that. Sure enough, followers began to pile in — but with two problems. First of all, the way I was acquiring pictures was not conducive to actually crediting the pictures, meaning that I had a good chance of getting into some hot water if an artist found out I was using their work without crediting them. Secondly, while the Instagram was popular, it was driving no traffic back to my site! Because my site, at this point, didn’t really have anything to do with art — it was all business and tech and that sort of stuff. So my Instagram strategy was worthless.

I decided to pivot. I got rid of all the art pictures, and instead just decided to advertise my new articles and newsletters. I made nice neat little canva designs, and scheduled out the Instagram posts with links to the relevant content.

This strategy turned out to be even worse! Now my Instagram looked as bland and dreary as a sweatshop, with the same posts (Newsletter #9, Newsletter #10, Newsletter #11…) appearing in the same pattern over and over again. Not only that, but I was actually losing followers now! None of my followers really cared too much about my website, and even the people I knew IRL began to get annoyed by my feed. It just wasn’t working.

At this point, I snapped out of the spell hexxed into me by the Social Media Mogul wizards. I realized that certain social media platforms worked for certain people. For example, Instagram is really only conducive to your platform if you are an artist or a photographer — nothing else, really. So I did what I should have done at the beginning: I deleted all my Instagram posts, and stopped there. Now I only occasionally post real photographs I made, with no real sharing or marketing intention, and — surprise! — they have better results than anything I tried in the past.

MonetizeNow that we’re done with that long-winded digression, we can get to the final piece of the puzzle: monetizing. Of course, the final plan of your work should always be to make a living out of it, just because of necessity. I believe that you can never monetize too early, but you can force monetization too early. You should never have to directly market your paid content, especially if you’re just starting out. Instead, just focus on driving people to your brand, and let them buy your products on their own. People don’t come to your app just because you built it — but people will pay for your subscription just because they came to your app.

The Day in A Life of a Working ProgrammeTo better understand what I’m talking about, let me take you through the lifecycle in full — with one of my recent posts as an example.

As I write this article, my most recently released post was Why You Might Want A Trading Account Over An IRA. Reading wise, this work was inspired a lot by writing done by Ramit Sethi, who often has interesting, contrarian takes on personal finance. In particular, he is a big proponent of having money work for you now, rather than later. Not in an epicurean, “spend to your hearts content” sort of way, but instead with the idea that when you’re old and dying you’re old and dying and when you’re young and healthy you’re young and healthy, so most of your big experiential purchases should happen now rather than later.

Thinking about this idea, I realized something: most financial advice on the internet almost completely emphasizes a 401k and IRA over a trading account. This didn’t sit well with me. A 401k/IRA being a good idea is one thing, but saying that you don’t need a trading account because all the benefits come from an IRA? Not necessarily. Pair this with some additional reading from Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money, which makes the good point that IRAs are too young for anyone to have successfully gone through the whole process anyway. In other words: financial advisors imply that you can invest in an IRA when you’re 18, and pop out at 65 a millionaire. But IRAs were only created in 1974 — 48 years ago! That means that, in order to have done when financial gurus claim, you would have had to have started your IRA within the first two years of its invention!

With this thought in mind, I went to crafting an article. I’ll save you the chore of reading about my writing process — it’s outside the scope of this blog, anyway. From there, I scheduled the post out and waited a few months until it came to it’s time to be published. I shared it to my social media, alongside HackerNews and my LinkedIn (I’m sure they got a kick out of it!). And then, of course, I made sure that my premium subscription was clearly indicated on the webpage — my monetization option of choice — just in case any of my readers were so curious.

The post Read, Think, Make, Share, Monetize appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

September 5, 2022

A Review of MyMind

I do not do product reviews on this blog often. The last (and first) time I did it was with YourStack, and while I’ve used a lot of tools since then nothing has particularly caught my interest. But the tides have changed yet again, and it’s time for me to preach to you all the gospel of MyMind.

MyMind (stylized as “mymind”) is a productivity/note-taking/bookmarking tool. I’ve used a lot of these in the past few years — Readwise, Instapaper, etc. etc. — but MyMind provides some interesting additions to the formula. The gimmick behind MyMind is essentially purposeful disorganization: you toss things in there, and worry about them later. This description might sound unappealing, but is actually very powerful in practice.

There are, as of now, three key features of MyMind: Search, Save, and Clear. Ironically, Search — despite being the feature they advertise the most — is the bad one. The only bad one, mind you, but still the bad one. MyMind claims to have a “machine-learning” approach to categorizing all your stuff — you can set up manual tags, sure, but the app will also automatically create tags based off the knowledge it infers about the site/image/notes themselves. The problem is that the search for this info is… not good.

Let me give you an example. Last week, I talked about reading Designing Virtual Worlds. Let’s see if we can search up “Designing Virtual Worlds”, and try and find my bookmark for it in the app.

…Well? Did you find it?

It’s at the bottom left corner if you’re still having trouble. I’d also like to point your direction to the scroll bar on this search. Hell, it’s not even something you have to infer — it’s a plain text note! It just has “Designing Virtual Worlds” written on it, for christssakes! What the hell does a Tim Ferriss book, Azure documentation, an RPG Maker plugin, and Jean-Luc Godard’s 1962 classic Vivre Sa Vie have ANYTHING to do with designing virtual worlds? How did you even get them to show up on the list? I can go as far as putting in the exact, one-to-one URLs and it will still not show up, or worse, pretend it doesn’t exist — forcing me to add it again only to realize that no, it was in there, it just didn’t show up.

Now, that all being said… part of this is a personal problem. I am a data hoarder, and as of writing this I have 8,475 entries in my MyMind pool. I’ve gotten other hints that the app isn’t meant to run with this many entries (such as the fact that it takes a full minute to load the list) so I am willing to give the developers some slack on this. It is also, like I mentioned, the only caveat I have about the app.

Now, let’s get to the fun stuff.

MyMind’s Save feature, by comparison, is a beautifully designed aspect. Not since Instapaper have I seen so many options to save content online — when MyMind saves you can put any trash you want in there, it really means anything. With the app and the extension, you can save websites, highlights (both on PC and mobile), website images, and more. You can also manually add files and notes if you wish. For some reason, some apps really kind of half-ass this. With my Notion clipper, for example, I can only save websites, making it inconvenient if I just see a small clipping within a site that I would like to go back to. This save function allows MyMind to walk the walk when it comes to its claim as storage for anything on your mind. The Save feature also provides a good segue into the third and final major feature: Clear.

This is the big one.

I don’t think I have ever seen a tool that feels so heavily like it was built for me as Clear. It is also so simple, I’m shocked I have not found another app with the same concept.

Here’s the idea around Clear:

You know that big, disorganized database of stuff you have lying around? Those 8,000+ bookmarks that probably cause a genuine disruption to the entire infrastructure? Let’s grab 10-15 of those, totally at random. Let’s then let you focus on one item at a time. Say it’s a reading, or a todo, or a video, or whatever else. You get two options: Keep, or Forget. Decided to finally read that article? Press the “forget” button, and it’s gone from memory. Want to save it for another time (again)? Press the “keep” button, and move on.

Let’s then let you focus on one item at a time. Say it’s a reading, or a todo, or a video, or whatever else. You get two options: Keep, or Forget. Decided to finally read that article? Press the “forget” button, and it’s gone from memory. Want to save it for another time (again)? Press the “keep” button, and move on. Once you finish with the full 10-15 item batch, you get a break. Once you’re done from your break — however long you want it to be — go right back into it, do another 10-15 item batch, ad infinitum.

Once you finish with the full 10-15 item batch, you get a break. Once you’re done from your break — however long you want it to be — go right back into it, do another 10-15 item batch, ad infinitum.There are a lot of things that I never get done, because there are either 1) scattered across many todos, reading lists, etc., or 2) Scary to look at and so I purposely avoid them. If I put everything all in one place, however, I no longer get those excuses. If it comes up in the queue, then well, God himself has deemed this 1/8000th chance and so I might as well do it. I am also very ADD and appreciate a system that gives me drastically different tasks to do one after the other, so that I never get bored.

I know my massive laundry list of items seems like I might push things off, but I’ve must’ve used the clear feature for about 6,000 items now, and god knows how many hours. It is the first productivity tool that feels addictive, it almost gamifies work in a way I haven’t seen since I chugged hours into 100% completing Habitica. Speaking of which, I do not dare find out what happens when you cross this with Habitica. Perhaps it’s time to renew the premium subscription?

But really, despite my poor thoughts on Search, I really do think MyMind has been a game changer for me. My only real concern is how much the company has been focusing on search over clear, but the app is still very much in its early stages and I imagine once blog posts like mine come out they might shift perspective. Or otherwise fix search, in which case I would not wish to be working at another productivity company because MyMind pretty much has the market at that point.

Anyway, go check it out! It is a paid tool but obviously I recommend it for its price. It also has a “demo” like free plan that I think would get you a good idea of whether you’d like to use the app or not. You can find MyMind here.

The post A Review of MyMind appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

August 29, 2022

A Few Thoughts on MMOs

Recently, I finished reading the book Designing Virtual Worlds by Richard Bartle. Made by the creator of MUD (widely considered to be the first MMO), it goes over best practices for creating a persistent, multiplayer experience. One thing I noticed about DVW right out the gate, however, is that it’s pretty old — so old, in fact, that the book came out just one year (!) before World of Warcraft, the game now considered to be the ultimate template in MMO-crafting. This antiquity made me curious… just how much have MMOs changed?

A few notes before we start:

This blog post was written out of order, and was originally designed to be a book review of Designing Virtual Worlds. As the post became less and less about the book specifically and more just my general musings about the recent history of MMOs, I decided to change the core topic halfway in. Keep in mind that because of this change you may find parts of the post which refer to this as a review (it is not).Bartle refers to these games by a wide variety of names — MUDs, MOOs, MUSHes, MUCKs, etc. Ironically, the term MMO — the now widely used term for these games — does not seem to have existed (or existed very loosely) when Bartle wrote his book. However, since the term MMO has now become overwhelmingly dominant, I’m just going to use that for the context of this post.Honestly, there may be newer editions of this book. The copy of DVW I read is a free pdf of the first edition hosted on Bartle’s website, and honestly I didn’t bother looking into whether there was further editions. That being said I don’t think that really effects this post as a whole, other than maybe opening up the discussion to Bartle’s views on how things have changed.With that out of the way, let’s dive in:

Introducing Designing Virtual WorldsSurprisingly, most of Bartle’s work has stood the test of time. At the very beginning of the work he lays out what he defines to be the “essential elements of an MMO”:

The world has underlying, automated rules that enable players to effect changes to it.Players represent individuals “in” the world.Interaction with the world takes place in real-time.The world is shared.The world is (at least to some degree) persistent.These elements still check out for MMOs to this day. For example, World of Warcraft has automated rules, players as individuals, real-time gameplay, and a shared/persistent world. About 99% of MMOs hit all 5 of these points, and all of them hit at least one.

Yet the world of MMOs which Bartle spoke of was very different. As I mentioned, this was written before WoW when the most popular MMO at the time was Everquest (the ORIGINAL Everquest, might I add). MMOs were still for hardcore, traditionalist gamers, and had the advanced and complex mechanics needed to satiate them. Unfortunately, as the market for games got bigger, this would become more of a hindrance than a help.

Lord British Fell Off (or the end of Old-School)Since Designing Virtual Worlds was written so early on, it separates the worlds of MMOs into approximately 5 eras, 90% of which take place during the old text-based generation. Obviously a lot of time has passed since all that, and history has dilated (as it does), so I am suggesting five new eras in its stead:

The MUD Era: The text-based era which Bartle, for the most part, lived in.The Ultima Online Era: The era marked by the dominance of Ultima Online and the beginning of visual-based MMOs.The Everquest Era: The era marked by the dominance of Everquest and proto-WoWlikes. This era was ending right as Designing Virtual Worlds was written.The WoW Era: The era marked by the dominance of World of Warcraft and the opening of MMOs into the broader market. This era was beginning right as Designing Virtual Worlds was written.The FFXIV Era: The era marked by the dominance of Final Fantasy XIV Online, in a world where it is not quite as cool to run an MMO anymore. This is the era we’re in now.Unfortunately, one of the sadder parts of reading Designing Virtual Worlds is seeing all the once household names that ended up falling to the wayside. Turbine, while it did see some years of success with Dungeons & Dragons Online and Lord of the Rings Online, is now mostly thought of as a zombie which every couple of years people say “Wow, they still exist?”, and move on. Richard Garriott (AKA Lord British), who created the first truly successful MMO with Ultima Online, tried his hand only one other time at MMOcrafting with Tabula Rasa, which subsequently failed. As of 2022, he is currently working on… an NFT game. Yikes. How the mighty have fallen.

Perhaps the one semblance of old-school’s remaining strength lies in Runescape. Yes, the game that — having been released in 2001 — was so unpopular at the time that it did not even receive a mention in Bartle’s textbook. Runescape’s true heyday was during the same time as WoW’s, where players who yearned for that classic experience got something that was easy to understand yet still had the freedom of those older games. And, sure enough, Runescape still has that place in people’s hearts to this day… this time in the reincarnation of, funnily enough, Old-School Runescape.

The WoW EraWorld of Warcraft, of course, is arguably what caused the death of old-school. It was a fundamental shift towards the “casualization” of the genre, both for good and for bad. I think few people will argue against the fact that WoW’s first three iterations — Vanilla, The Burning Crusade, and Wrath of the Lich King — are some of the best MMO experiences ever made.

WoW did two major things that broke away from the old-school formula. The first was that it stripped down a lot of mechanics in favor of instant gratification. You’re always getting fancy level-up proclamations, always getting new gear, always gaining new skills that give off cool new effects. The reason for this change leads into the second — the focus on endgame content.

For most of us modern players, it’s hard for us to remember a world where endgame wasn’t the focus (with the exception of FFXIV — we’ll get to that). The idea of ignoring all the early content to get to max level as soon as possible is a depressing notion, but in a lot of ways it makes sense. For example, it’s a lot easier to balance stats if everybody happens to be on the same level anyway. It also makes a lot of sense lore-wise for everyone to have the cool, crazy armors and weapons only after they’ve mastered all the other content.

Now, take in mind while these changes might seem negative, this isn’t an indictment of WoW. In fact, I much rather prefer the mechanics of WoW to what older games did. All games are essentially a balancing act between making it easy for people to play and adding complex actions that make the game immersive and fun. Traditional MMOs leaned a little bit too far into the realm of complexity — what WoW did was restore the balance.

Of course, with WoW’s popularity came a popularity for the genre in general. And you know that there were plenty of companies out there looking to take a slice of the cake…

Rehashing Ideas (and the Fall of WoWKillers)Early on in Designing Virtual Worlds, Bartle makes a deeply foreshadowing remark:

…some designers look too hard at what has gone before. To use some admired virtual world as a prototype is fine if you fully understand that world, but very limiting if you don’t. A designer whose major experience of virtual worlds is EverQuest might, for example, think ‘what character classes should we have in our new game?’ rather than ‘should we have character classes in our new game at all?’ Some of the more basic assumptions go right back to MUD1, with few designers even realizing that they are assumptions, let alone that they can be questioned. That can’t be right!

In fact, Bartle brings up similar points a lot throughout DVW. Like, a lot. Well, if DVW was ever required reading for MMO-Crafting 101, a lot of people must have skipped class because the ten or so years after WoW’s inception were marred by lookalikes.

Mockingly referred to as “WoWKillers”, these games claimed lofty and ambitious features while at the end of the day being nothing more than a glorified copy of WoW. While there are too many to list out, four are of particular note: Guild Wars, Rift, Aion, and Star Wars: The Old Republic, or TOR as it is more commonly referred to.

Out of all these games I am willing to give the most benefit-of-the-doubt to Guild Wars, as it 1) made a decent attempt to differentiate itself, and 2) is the only one of these four games that is still alive and has a healthy user base. Guild Wars was originally released in 2005, with a somewhat less successful sequel being released in 2012. As the name implies, the game had a unique focus on PvP, with a wide variety of competitive modes available including the legendary World v. World mode. In addition, the game’s story — albeit not very good — had its own voice within the game, playing out more like a single-player campaign (once again… we’ll get to FFXIV when we’re ready). All in all, the game does have its strong points — but in my opinion leans more towards the side of a WoW-like than a true experimental MMO.

On the other hand, we have TOR. TOR is perhaps the most notorious of **the WoWKillers — built with the full backing of Electronic Arts and the Star Wars brand name (more specifically, the Star Wars: Knight of the Old Republic brand name) this game was hyped to hell and back as the game to finally dethrone WoW. Unfortunately, it landed when consumer sentiment for Electronic Arts was at an all-time low (it won worst company of the year 4 years in a row) and people were beginning to lose faith in Bioware after its horrid showing with Mass Effect 3. As it turns out, people’s fears were founded: TOR turned out to be nothing more than WoW with a coat of Star Wars painted on. The game did improve in later years, focusing more on its differentiation in storytelling, but lately its players have dwindled and it appears to be on its way out.

And finally, we have Rift and Aion. Rift and Aion were both big on their initial releases, but as of now have mostly been lost to time. Rift was perhaps the most direct competitor to WoW, and in many ways just claimed to be WoW but better. To be fair, in some ways it was — I still hold a soft spot for Rift, and its eponymous rift system (which WoW later copied!) was a genuinely neat idea. Aion, meanwhile, was NCSoft’s biggest attack on WoW’s success. NCSoft, who had been the publisher of many successful MMOs (including Guild Wars), put together their resources on Aion as a means of becoming a self-made WoWKiller. And in the end, the game was… forgettable. So forgettable that I checked the Wikipedia page to remind me of what its major features were and I still don’t remember anything about it. Such is the fate of those MMOs who tried to beat the king.

The Curse of Sci-Fi MMOsI want to make a digression here to talk about something that doesn’t quite follow chronologically. At some point in DVW, Richard Bartle mentions three franchises that would fit perfectly as MMOs: Star Wars, Star Trek, and Lord of the Rings.

Oh, Richard. If only you knew.

To his credit, all three of these franchises would eventually get their own MMO games (out of all of them, only Star Wars Galaxies was under development at the time the book was released). Yet, despite their seemingly “perfect fit”, all failed to gain considerable market share. Why?

For LOTRO (The Lord of the Rings title), there doesn’t seem to be anything besides bad luck: the game was released at around the same time as the much more popular Dungeons and Dragons Online made by the same developer, and that likely took away from its success. But what happened with Star Wars Galaxies and Star Trek Online, two huge properties with massive budgets and a community that is heavily engaged?

Well, Star Wars Galaxies marked what many refer to as a “curse” among science fiction MMOs. At the time of the release of DVW, sci-fi MMOs seemed to live a healthy existence. But as games went from a text- and 2d-based perspective to a much richer 3d-world, these games seemed to collapse in favor of a fantasy setting.

The obvious finger to point to seems to be with the ambition of sci-fi versus fantasy. Instead of a small traditional fantasy world, you’re dealing with a whole solar system of planets, races, starships, etc. etc. And with that added content comes added costs, added costs which — given the already heavy expenses of a live service game — can be too unfeasible to do properly.

Of course, that hasn’t stopped people from trying. I’ve already mentioned TOR, which in many ways is a spiritual successor to Star Wars Galaxies. We already know how that turned out. And while on the topic of sci-fi MMOs with huge budgets, Destiny is worth mentioning. The game is still played, but its original scope (and funding) was significantly reduced than the multi-billion dollar project it was originally meant to be. Warframe is a sci-fi game that is still going strong, but is missing many of Bartle’s key criteria and is seen more as a multiplayer character action game than anything else.

Ironically, the only Sci-Fi MMO that has seen widespread success is the one which Bartle mentions only offhandedly and as an example of failure: Phantasy Star Online. To Bartle’s credit, he was referring to the first game — its sequel is the one that has seen widespread acclaim.

The FFXIV EraOut of all the eras we previously discussed, the newest one — which marks the dominance of Final Fantasy XIV Online — is the strangest.

First of all, really no one could have predicted FFXIV’s success for decades. As Bartle mentions, Final Fantasy XI was a moderate success, but nothing to write home about in comparison to the releases of western games like Everquest, World of Warcraft, or even Star Wars Galaxies. Combine that with the fact that Final Fantasy XIV was a horrid failure on launch, you could have only really expected any sort of success from it, at earliest, upon the release of A Realm Reborn — 3 years after the initial XIV launch and 10 years after Designing Virtual Worlds.

Final Fantasy XIV takes almost every idea that Bartle says makes up a virtual world and throws it in the dumpster. For starters, FFXIV treats its game like a very long singleplayer RPG with an optional multiplayer element. They have notoriously said they don’t care too much about whether people stay subscribed, recommending that people only subscribe for major story or content updates. And even then, a good chunk of the game is entirely free-to-play. There is also no real focus on PvP, the cornerstone of many MMOs in the past, and most of the content is completely cooperative. The narrative reinforces this, as well.

And yet, out of all the games, it was FFXIV that one. Why?

Well for starters, we’d be fools to say that it wasn’t at least partially WoW’s own fault. Over the years, the MMO began to get into the extreme end of casualization, trying too hard and too desperately to gather as large of an audience as possible. This alienated a lot of its already existing fanbase, while new players were overwhelmed by the large amount of hacked-on features that were created over time. FFXIV just happened to come at a time where this mass migration hit its critical point.

Yet there are a lot of MMOs on the market, and to say that FFXIV’s success beyond all the others was just pure luck… leaves something to be desired. One reason that potentially explains things is that FFXIV fit with the culture of modern audiences. WoW was built on by engineering-minded nerds who lived in their mother’s basement, while zoomers are feelings-oriented art kids who live in their mother’s living room. Many of these newer gen folk came to WoW, got confused as to why someone was telling them to kill themself after failing to pull a mob properly, and subsequently went to FFXIV.

There are a lot of theories as to why FFXIV is culturally different from WoW. One of my favorites is from Jesse Cox, who makes this distinction: WoW is inherently player-versus-player, or competitive, whereas FFXIV is inherently player-versus-enemy, or cooperative. In FFXIV, competing against other living people is virtually nonexistent, and when it does happen it’s usually put in a sports-like, friendly competition sort of fashion. In Warcraft, the entire game — both its story and its gameplay — revolves around people fighting and killing each other for honor and glory.

I think another reason for the cultural difference, and why the newer generation attaches to it, is Final Fantasy’s — stay with me here — metrosexuality.

I’ve already mentioned why the zoomers of the present are different from the boomers of the past. While older generations thrived on semi-realistic fantasy tales told in homogenized settings with white male protagonists, the newer generation has craved for much more flavor. Part of that is because they are more diverse themselves, for sure — but I think another part is that they are just tied of it. They want to see what else is out there.

Final Fantasy, once a game for the ultra-fringe weirdos who even Warcraft fans didn’t interact with, seems like the perfect ticket. The world of Final Fantasy is colorful, abstract, weird — its characters blend together in gender, race, and identity. It is a story of friendship, of overcoming odds, and not of war and glory. It is an adventure, but a different kind of adventure — an adventure that just happens to now be in vogue.

But perhaps the biggest takeaway of the FFXIV era is how far MMOs have fallen in popularity. Yes, it’s true, FFXIV’s peak player count has surpassed WoW’s. But even this number is minuscule in comparison to the wide array of other multiplayer games available — Fortnite, League of Legends, Among Us, etc. There is still room for MMOs — billions of dollars worth — but it has now become more of a niche than the craze that it was in the WoW days. In other words, perhaps we’re just back to the way it was when Designing Virtual Worlds was written: a niche genre to play around and have fun in.

The post A Few Thoughts on MMOs appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

August 22, 2022

Why NFTs Don’t Work For Games

Crypto gaming and pay-to-earn is a classic case of people being ignorant to history and making the same age-old mistakes. Here’s why.

(tl;dr: Something something beanie babies)

Those of you who know me and read this blog know two things:

I am not holistically anti-crypto. I have sizable stakes in Braintrust and Gitcoin and have often gushed about how crypto can solve problems related to grant-making, freelance work, etc. Hell, I am not even necessarily anti-NFT — while I deplore those ugly, glorified profile pictures with the same integrity as a late 2000s Newgrounds dress-up game, there are a lot of artists out in the NFT space who putting in honest, wonderful work (see Oreste Mercado’s photography or Daeho Cha’s Weirdo Witches series)I have always (meaning, pre-crypto) had a problem with play-to-earn games. While I don’t want to spoil this entire blog post right in the introduction, there are some reasons for which games fundamentally do not work as earning vehicles, at least in any serious aspect.This article is not meant to be some inflamed polemic against NFTs in games — a lot of people have already done that. Rather, this is meant to be a somewhat boring, realistic, and (in some ways) depressing analysis on how gaming NFTs cannot work. I am not making moral arguments here, I am making technical ones.

With that in mind, let us begin.

Problems with Intersectionality

Gaming is cool because it provides an intersection between art and technology. It’s a relationship I’ve talked about before, but one of the caveats I had mentioned is that sometimes there are people who are too in the art side or too in the technical side and just don’t get it.

Anyone who has played games can immediately recognize that the future in which the above LinkedIn post describes fucking sucks. First of all, no one wants to spend two weeks grinding for “better weapons” — perhaps if you are a power user, but power users typically do not consist of more than 5% of a games total player base. Secondly, the balancing issues that would occur out of item cross-contamination on this scale would likely be astronomical, even assuming that all these games were made by the same developers (it seems like the implication is that it is the same chain but widely differing games). Funnily enough, the power users I had mentioned would likely only be interested in focusing on one specific game and not a menagerie of them.

A quick look at Nicolas Vereecke’s profile and, surprise, he has only ever worked in tech and investing and not in game development or other entertainment media (he also now has a profile picture of a black Cryptopunk character which I think is very funny). Mr. Vereecke’s ideal world exists only in his head — it fails in execution, likely because he does not know what users want, likely because he hasn’t actually played that many videogames in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, Vereecke’s post was absolutely lambasted all over gaming Twitter. But looking at things deeper, there’s a more fundamental, subtle issue with this post beyond power-gaming and balance-scaling.

People don’t want to make money playing games.

Yes, I know, all the hiveminders and junior business boys in the audience just recoiled. “What, people will actively decline a chance to make money???”, they ask themselves. Yes, not everyone is on that hustle grind, and games are especially in this category. This is because games are made specifically as escapist vehicles, — to relax and move away, however briefly, from the reality of paying the bills and working a 9-to-5. Creating an avenue where in many ways the goal of the game is to make money, or to otherwise grind for hours on end, comes into direct conflict with that idea.

Still, this only explains why NFTs might not work. It is not a strong enough argument for why NFTs cannot work. To explain the deeper issue at play, we need to first take a history lesson.

The (Sad) History of Play-To-Earn Games

Play-to-earn games, I can only imagine, have existed since the beginning of time. But the start of P2E as we define it today was primarily influenced by two games: Second Life and Entropia Universe.

(Side note: Yes, this next section is going to sound a lot like my Metaverse article. Keep reading as we’ll diverge on a few key points)

Second Life was the first true attempt at a Metaverse game. It involved virtual people, living virtual lives in virtual worlds — and, yes, that meant a virtual economy.

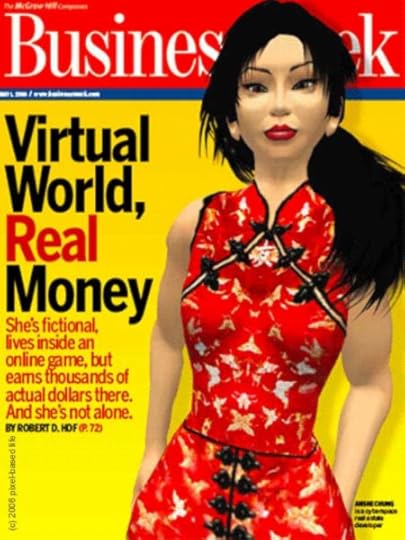

When Second Life was big (and, for a while, it was very big), its economy was thriving. Anshe Chung, the virtual character represented in the above BusinessWeek cover, was pulling in millions in crisp green dollars solely by buying and selling virtual land with no true physical equivalent (sound familiar?). Entropia Universe, a game with a similar premise that came out around a similar time, was also seeing high-powered deals during its heyday — including a space station for $330k and a night club for $635k. For a while, it was good to be a play-to-earner in the metaverse renaissance.

Then, the players stopped coming in.

It was around the turn of the decade, and a new generation of games was coming in. People were no longer interested in the Metaverse future, and besides that the engines on which these games were built were beginning to show their age. People began to trickle out, and the real estate prices fell. The Titans of Second Life once again found themselves needing full-time jobs, and the game deteriorated in popularity to the point of just being the occasional butt of a Youtuber’s joke. The P2E dream, as it stood, was dead.

Sure, there were other attempts in the meantime. Valve has experimented with the idea of P2E with its Steam marketplace, while Blizzard tried the disastrous auction house experiment. But the concept of play-to-earn in its original philosophy — of playing a game to earn real money — was never attempted on a full-scale again. Well, of course, until crypto happened. In the words of Mark Twain: History doesn’t repeat itself, it just rhymes.

But why exactly did the P2E market in Second Life fail? Certainly there are good reasons for the game falling in general popularity, but in the ideal P2E future even an obscure game can net a power user a hefty profit. It is here, my dear reader, that we get to the crux of the argument presented in our title — why NFTs don’t work for games.

Foundations of Economic Value

I had mentioned the idea of economic value somewhat offhandedly in my Metaverse article, but I did not go into it as the economy is really only a small segment of the Metaverse puzzle. VRChat, Roblox, and Meta currently do not have any virtual-to-real economic system in place, despite being Metaverse frontrunners. But now that we’re talking about P2E and NFTs, it’s time for the “economic value” keyword to come out in full force.

Economic value, a keystone in economic theory, is the value that defines a market’s existence. People buy and sell things that give them value in some way — make things easier for them, make them happier, etc. etc. For example, there is a market for computers because they are nifty little things that provide a lot of utility and entertainment for our daily lives — they provide economic value.

The best way to explain why gaming NFTs/P2E doesn’t have economic value is to start with things that do and slowly add on derivations until we can see why P2E is the major breaking point.

The games themselves, of course, have plenty of economic value — the ability to entertain, to inform, to teach, etc. etc., depending on the purpose the game serves. But, one might ask, what about experiences external to these games — primarily, livestreaming them or playing them as a sport?

Well, these two concepts provide pretty clear economic value as well, and a big reason why they do is because, if they are external to the game, then they do not rely on the game to function. In other words, people do not usually watch a livestreamer because they care about the game they’re playing — they watch a game because they care about the livestreamer. Similarly, esports typically revolve around genres of games rather than games themselves. Take the FGC, for instance — EVO tournaments are many mini-tournaments for many different fighting games. There are certainly big tournaments for individual games, but the idea is that a person who is skilled in League of Legends can easily, if needed, transfer their skills to DOTA 2. Or a Fortnite player to PUBG, CSGO player to Valorant, etc. etc. Thus the economic value comes from the external factor, NOT the game — it comes from the livestreamer’s ability to entertain, or the esports event’s ability to be engaging.

But what about internal derivations? For example, we can talk about a market for user-generated content, or UGC. Well, markets for UGC work to an extent. Within a game, people are willing to pay real money for a user-generated item (a developer-generated item (DLC) counts also) dependent on their enjoyment of the game. So yes, UGC does provide value as it may help someone enjoy the game better, but it is moreso dependent on that game’s own economic value. The technical name for this is a “complementary good”.

The initial success of Second Life’s play-to-earn system was marked by these complementary goods — more specifically, the real estate which was designed and bought (ironically this falls more under UGC than P2E, more on that later). When Second Life was very popular, this market boomed. But once its popularity dwindled, the market became almost nonexistent. So UGC provides economic value, but it’s fickle and oftentimes ethereal to boot.

And now we’ve reached play-to-earn.

The thing that differentiates UGC from play-to-earn is that UGC is taking concepts outside the game and making them internal, whereas play-to-earn is deriving value specifically from the game. Let me say that in English: an example of UGC is someone making a rigged model in Unity and selling it for use as a VRChat avatar, whereas an example of play-to-earn would be killing mobs in Entropia Universe, gaining credits, and then converting those credits to USD. You are literally playing to earn, not creating to earn as in the case with UGC.

The problem with this is that there is no value generated from playing a videogame. Nobody really needs you to kill those mobs, or craft those items, or grab that “Immaculate Orb of Brilliance”. You are not benefitting the world in any way by doing these things, beyond giving yourself some enjoyment in doing it. All it boils down to is the videogame developer itself giving you some incentive to keep playing, which can only keep going as long as the developer’s coffers are full.

Some would argue that illegitimate item farming — for example, in Diablo — is an argument against this idea. It’s why Blizzard tried that aforementioned “real money auction house” idea in the first place. But, of course, we know that failed. It failed because in practice there’s no real reason for me to buy someone else’s loot that I can just get myself, and especially so if I can just buy a level boost straight from the developer.

And then, of course, there’s the point that I made at the very beginning of all this: people don’t want to make money playing video games. Video games are meant to be fun, and if you’re playing them in order to work then it’s a job. Sure, you can create a job out of making stuff for games — livestreaming, esports, UGC, etc. — but not out of just playing them.

The NFT Angle

Now, I sense that some of you might be getting a little impatient, as I have been talking primarily about “play-to-earn” and not about NFTs, which are not inherently the same thing. The example which Vereecke originally gave does not necessarily have anything to do with making money playing a game, but rather just creating an interconnected ecosphere between many different games. What gives?

To be fair, NFTs, crypto, and play-to-earn are all separate concepts. They do not really have anything to do with one another, at least if you were to split them up into their separate definitions. However, my view is that when you do one of these for a game, you’re essentially doing all three.

Let’s go back to the Vereecke example. His business and investing background aside, there are hints within his post that seem to point to the idea of not just a crypto or NFT gaming future, but a pay-to-earn one as well. For example, that enthusiasm for grinding that I made fun of begins to make a lot more sense when there is a real, tangible value to the item at play. The value of an “Orb of Brilliance” likely doesn’t just come from the fact that it’s glorified preorder DLC — you could probably sell that in some sort of market, too.

Oh, speaking of preorder DLC, those are turning into NFTs also. The idea with Ubisoft and Square Enix’s NFT ideas (which, to be fair, at the time of writing are both in limbo) is that not only would they make profit on the initial sales, but then gain royalties on every sale after. That system doesn’t work unless there is some sort of concept of play-to-earn in place (or perhaps you could be bold and argue that this is “investing”). And so, if you have crypto and NFTs, and you put them into a game, you inevitably have a P2E system in one way or another.

Anyway, I’ve reached the end of my great lecture. If you disagree with me (or perhaps agree but would like to add some more wood to the fire), you can put it down in the comments so that people know about the other sides of this. The next post on here will be equally large but on only a tangentially similar topic. Sorry for the wordwalls, we should be back to short posts after that.

The post Why NFTs Don’t Work For Games appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

August 15, 2022

Why You Might Want A Trading Account Over An IRA

Alright, so this may be one of my more controversial takes. But I really don’t think investment plans – IRAs, 401ks, etc. – have any distinct advantage over a normal, traditional trading account. There is one particular reason why I think this is true, but I’ll dive into the details within this post.

One caveat before this starts: I am not saying you would never want an investment plan. I have an investment plan in the form of a 401k, just like I’m sure many of you do. On an individual basis, there’s good reason to get 401ks. If you are a risk-averse investor – that is, you don’t like stock picking and you freak out every time the market fluctuates – you’re better off just getting a 401k because of the fact that you never really have to think about it in your 60s. You’ll see as I describe my case against investment plans that my case doesn’t work for everybody. Just want to make that clear right in front.

Another thing I want to point out is that I am not saying investment plans are inherently inferior to trading accounts. I just don’t think they’re superior to them, either. Like I said, this really depends on the person.

Alright, with that out of the way, let me get to my argument. The main crux behind why people say IRAs are better than an investment account is the tax advantage. In simple terms, a Roth IRA gets rid of capital gains tax. That means that you pay into the fund, the fund gains money, and when you cash out in old age you get all the money back plus gains. In a trading account, by comparison, you lose 15% of gains on sales past a year and 25% of gains if you sell within the year.

That number is nothing to scoff at! Over the span of 40 or so years, an investment account can gather quite a bit of gain – and the fact you don’t have Uncle Sam taking a 15% bite out of it becomes more and more beneficial.

But there’s a key issue here.

The stipulation behind most investment plans is that you can only withdraw the money at a certain date. For IRAs, that’s about 60 years of age. If you withdraw before this time, you pay the standard tax plus a 10% fee. In other words, you’re paying short-term tax for long-term gains!

It’s true that there are exceptions to this – for example, early withdrawals are allowed in order to supplement house purchases. But I think overall the IRA system makes the inaccurate judgment that you aren’t going to need to dive into your investments until after you’ve hit retirement age.

It is my philosophy that investments should be treated as savings. That is, you only take investments out when you need the money for an emergency case. A lot of the time, however, that emergency is going to happen far before you’re 60 years old – and often won’t be part of one of the IRA’s withdrawal exceptions.

With this in mind, my argument is that the 15% long-term tax premium is worth exchanging for liquidity (not the short-term tax premium, you should never sell investments in the same year). In my mind, I am willing to pay 15% on gains if it means I get to sleep easier at night knowing that if I become sick or lose my job tomorrow, I have easy access to a pool of funds in my investment account. I do not have this same promise with investment plans.

This, of course, is subjective. It’s the reason why I’m not saying investment accounts are superior to investment plans. But I think a reasonably large amount of people would agree with me here to the point that it’s worth writing about so that people know IRAs aren’t necessarily the great savior they’re made out to be. My recommendation (particularly to risk-conscious investors) is to always have an individual trading account that regularly deposits money to an index fund, and treat that as long-term savings. I would also still use both tools – it’s not a one or the other decision! Like I said I personally have a 401k, and I really do not look at it at all. I’m treating it as a nice little gift at old age, that perhaps I forget about and one day get the notification of “here’s a nice hunk of cash you now have access to, congratulations!”. But my focus, at least for now, will always be on liquidity in savings.

The post Why You Might Want A Trading Account Over An IRA appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

August 8, 2022

Explaining my Rating System

Yes, I know. No one asked. HOWEVER, as I write this it is late on a Sunday, April 24th 2022, I am too tired to write anything meaningful and I still need to get my word count done for today. So, here is a free ghost post that will only be directly advertised to WordPress followers, about my overly meticulous rating system for my art media catalogs.

Those of you who have followed me for a decently large amount of time know that I have a very odd obsession with cataloging my taste in music, movies, games, and books. For me it is a fun pastime, and I often get pretty deep into it (perhaps too into it, but that is a topic for another time). So, in this post, I want to describe how exactly I catalog said taste, perhaps only for my personal records but also on the off chance that you, the reader, are also into this strange thing. This post will also probably be more of a stream of consciousness because, like I said, it is late and I am tired.

So I guess the first question you’d be interested in is the why. Why does it matter, that you saw The Last Unicorn on July 25th, 2021, and thought it was OK? Well, part of it is personal commitment. I am in this game, I make fiction writing, I develop games, and I sometimes dabble in movies and music. For me, if I have a catalog of what I’ve seen, I get to think critically about what works for me and what doesn’t. For example, I know that Safe (1995) is one of my favorite movies, and there are a lot of ideas from that movie that I can later incorporate into writing. By cataloging it I remember the impact it had on me when I watched it, even if I write no specific notes on it – the memory is there, encased in a Letterboxd entry and a rating. On a similar level, I get to see what doesn’t work for me. I get to give Bicycle Thieves a 6 out of 10 and then defend myself against the sycophant arthouse enthusiasts on why I think that movie is not really good (even if said sycophant arthouse enthusiasts really only exist in my head). This further informs what I would like in writing.

A big chunk of what I do, inspiration-wise, with art media is that I sample a big chunk of the world’s greats, and I see what motifs I enjoy and which I don’t. Having a lot of control over what you know specifically you like and don’t like makes the writing process a lot easier. It makes it modular, in a way, but not such that the creativity is fully gone. Cataloging and rating are the long-term memory for that.

Anyway, with the why done, let’s talk about the how. I’ll start with DNFs, because they’re the most tricky. I’ve mentioned before that I don’t like to DNF on books, for personal conviction. I also rarely DNF on movies and music, because they are so short. Really the only reason I DNF for these three is that I find the work so awful that leading myself to the finish would be unbearable torture. It doesn’t happen often, but it does happen. For games it’s a bit more complicated – a lot of games take 30+ hours of real work, and I have several hundred of them accumulated (mostly from free giveaways) over the years. For games, DNFs are less extreme. They’re simply measures of “this game didn’t really rope me in, and it seemed rather long, so I’m not playing it. For the first three, I tend to give DNFs a 1-star rating. For games, I don’t give any rating to DNFs at all – though if I had to say, a DNF on a videogame is probably 7/10 and below.

This transitions us nicely into the rating distributions themselves. Firstly, I try to regulate things on an out of 10 system – some services use the 5-star system, others use out of 10. I am used to 10, though sometimes I mention a review in the 5-star format. My “average anchor” is typically 6 to 7, across all 4 media. Yes, I know, I am one of those dirty modern critics who don’t even use 90% of the damn number scale. Well I like going up to 10, even though I really don’t use 3-5, and I live in America and we have something called freedom of speech. I’ve done it once, and I’ll do it again.

The middle point (we’ll say 7 for simplicity) represents a work I believe others would enjoy, but I personally do not like. I suppose for the majority of the population this would look more like a 4/10, but I like being nice. So for 7, I see it, but it’s not for me. It is very, very rare for me to get an idea inspired by a 6 or a 7. They are basically “in one ear, out the other” sort of deals for me. 8s I do enjoy, but it’s also rare to get inspiration from them (though it does happen, more than 7s). 9s and 10s are where the magic happens – this is where I say “Okay, this is really good, there’s something in here I really enjoy. Let’s dive deep into that.” The Holy Mountain, House (1977), and Pink Floyd’s The Wall were all 10s – all abstract, dealing in philosophical themes, dreamy landscapes, nothing really on concrete facts. I took note of that. The Peregrine got a 10 because, even though I do not give a shit about falcons at all, the flow to the writing was there. I want Peregrine flow in every book I write. I won’t get it, but I’d like it to be that way.

Then you start getting towards the opposite angle. Like I said I rarely use 3-5, but sometimes when I feel there are bits and pieces there but the thing mostly falls apart, I’ll use those to describe it. Yet once again, we see the 1s and 2s, and again get inspiration. These are sort of the anti-patterns. What do I hate? Wuthering Heights had writing that made reading that book the equivalent of watching paint dry. Alright, compare and contrast that book with The Peregrine. What’s different here? Well, it doesn’t have the flow. It doesn’t have the imagery. Write that down. Maybe you think the opposite – why? Write that down. I gave Buffalo Springfield’s self-titled album a 1 (much to the chagrin of a few soft rock-minded friends). Why? It was too slow-paced. The rhythm wasn’t there. I look over at the 10s – all fast-paced, energetic, noisy, keeps you guessing from song to song. What does that mean? How does that translate into the writing?

So hopefully you can see why both the real bads and the real goods are beneficial. The stuff in between, not so much. But even then, it can. Remember back at the beginning of this post, when I said I gave Bicycle Thieves a 6? Well that’s really relevant now, because Bicycle Thieves is one of the most acclaimed films ever made. The Safdie Brothers would kill me if they found out, EXCEPT, both Safdie films I gave an 8/10 to! How can I hate the film that influenced these directors the most, and yet like both of their movies? Well, that’s the magic of creative execution. They saw something in Bicycle Thieves I didn’t. They grabbed that piece and put it in their films. Turns out, it’s a good piece. I just didn’t see it. Sometimes you don’t see it. That’s fine! Read widely and you won’t have to see everything.

I gave Come and See a 3/10. Now that’s something to talk about. We’re talking one of the top 10 greatest films, on everything – IMDB, Letterboxd, The Film Institute, magazines, etc. And what’s even more shocking – I gave it a 9/10 when I first finished! What did I see then? Well, I saw a horror movie. I saw the beginnings of Eggers and Aster. And I still do see that, and I still believe in that origin point. But the more it marinated in my brain, I realized – no, no, this was never intended to be horror. Klimov didn’t see it that way. I saw it that way, because I was living in (2020 at the time) and I was amidst the modern horror renaissance, and I saw that renaissance in his film. But Klimov wasn’t around for that. He made Come and See because he was angry – he was making a statement. A political one, a philosophical one, a psychological one. I went back and reviewed the movie on that statement – it was reckless! Absolutely reckless. That film had so much merit as a horror movie, but then it became a war movie – perhaps not a war movie, a film about war (it’s different!) – and I hated it. Once again, we look back in the archives and see the counterpiece. For me, it’s The Battle of Algiers (9/10, only for a meandering ending). I look at both films, and I see it immediately. It’s morality. Yes, that dirty word on this website makes its way into my taste in film as well. Battle of Algiers was relative; it did not pick sides. It gave you someone to root for no matter what angle you looked at. Come and See chose sides. Or, in some ways, it did worse – it did not choose a side at all. You came out of Come and See and, if you took it seriously (which apparently I did not, haha), you gave yourself a negative viewpoint on life that was unproductive and didn’t really teach you anything besides the world is bad. That came out of Klimov’s view that the world was bad, that it was destiny for men to kill one another, and while that’s not the reality of the universe that’s what he transcribed his work to be. You see why I think it’s reckless now.

You can have these deep, introspective thoughts when you review a lot of art. Perhaps you have a different opinion, perhaps you’re one of the people who far outnumber me who do genuinely believe Come and See or Bicycle Thieves or Wuthering Heights to be one of the greatest works of all time. Good! But dive into that. Understand why you enjoy what you enjoy and dislike what you dislike. And perhaps a good place to start doing that is to catalog what you’ve already done, and set a rating system up on your own.

The post Explaining my Rating System appeared first on Jacob Robinson.

August 1, 2022

Political Theory and Evolution

Almost all of modern-day politics revolve around one key idea in evolution. Let me explain why.

As always, let me start off by making a sweeping generalization. In the modern times we can usually put people, politically speaking, into two different buckets: conservative or liberal. There may be others, but they are usually just different flavors of these two groups. Conservatives, generally speaking, believe things are good the way they are – they prefer little change to the social structure. Liberals, on the other hand, are never happy – they always dream of a better world, and work fervently to get us there. The balance of the two of these is what makes good political order. If one side becomes too powerful, things become imbalanced, and what you end up getting is at best a status quo and at worst a few years (or decades!) of political strife.

This last point I think is why it’s important to understand the fundamental principle of why politics is the way it is. You need to have both sides of this coin in order for society to function. And this coin is, of course, evolution.

What does politics have to do with evolution? Well, think about what I said. Conservatives think things are good the way they are – they don’t think we should evolve, or otherwise evolve more slowly. Liberals always dream of a better world – they want us to evolve at a faster rate.

It’s ironic, for politics to take on the form of evolution before most politicians even believed evolution was real. To be fair, this is more a form of cultural evolution, but evolution nonetheless. The balance of these two forces develops the mutation rate. If the mutation rate becomes too slow, or too fast, chaos ensues. Because of this, a bit of (healthy) disagreement among a Republican and a Democrat goes a long way.

July 25, 2022

Fitness, Suffering, Self

For years I tried to get myself motivated to exercise regularly and intensively, only to fail every time. It was only until recently that this changed. My solution, like most of the things on this blog, was roundabout – but just like the others, it’s worth discussing.

Let me start off by describing to you my troubles. Exercise and diet were always the hardest positive habits to keep in mind for me. They seemed, in a way, like suffering. Making yourself feel worse now to feel better later. Well, I certainly didn’t have the time for that!

Eventually, during the big “incremental growth” personal revolution in 2019, I tried to cut a lot of habits I wanted to work on into smaller, more reasonably-sized chunks. Diet and exercise were naturally the number one targets on my crosshairs.

This is where things got complicated.

For dieting, the 1% task is easy. Just don’t buy junk food or go out to eat, and in a few weeks you’ll forget that food existed. But for fitness, I soon found out there was no shortcuts. Sure, I could just do a few pushups until I got tired, or try out some equipment at the gym, and as long as I did it consistently I was following the 1% guidelines. But fitness demands much more out of you, and I soon found out that – improvements from diet aside – I wasn’t really getting any stronger or fitter.

You see, fitness demands intensity. Intensity, by definition, conflicts with the 1% philosophy, whose whole purpose is making things as simple and quick as possible. Not a whole lot conflicts with the 1% philosophy, but here I found myself matched with one of those rare exceptions.

So I couldn’t just make fitness easy, I needed to make intense fitness easy. This didn’t require a life hack – this required an entirely different mindset.

Fortunately this mindset change came to me in the form of a set of experiences sometime in 2021. The first was an interview (or a blog post, not sure on the exact form) with Jocko Willink, who alongside David Goggins is quickly becoming the messiah of fitness. I remember he gave something similar to this analogy:

“[The reason you work out is] somewhere, there’s a guy out there with a grenade in one hand and an AK in the other. Every day, he gets up at 5 am, and trains. He trains, and his only goal is to kill you. How do you react to that?”

To be fair, the literal interpretation of this probably works far better for an ex-Navy Seal than the average person sitting on their ass. However, we’ve learned from The Book of Job and Life as War that there is still some truth to be found in this statement. The metaphorical “man with a hand grenade” is a lost job, or a death in the family, or some other equivalent. If you’re not prepared for that – mentally or physically – then you’re much worse off.

This is what brings us to the title of this post. Fitness, in general, is an activity of suffering. It is you suffering for a given amount of time in exchange for some gains to your health. Usually that suffering isn’t worth it – but if you reframe that suffering as controlled training for suffering in the future, something changes. The suffering is no longer empty, but rather preparation for some far off event. Defense against the hand grenade.

Some people do just fine treating fitness as a way to get healthy. But if you have trouble with this, try thinking about it in a new mindset. See it as preparation – not just for your body, but for your mind as well.

July 18, 2022

The New Working Class

When companies like DoorDash, Uber, and Instacart provided new avenues for people to work flexibly, many got excited. Now that it’s happened, our hopes aren’t quite as sweet… but here’s how things can still get better.

The working class has changed a lot over the last few centuries. It used to be farmers, then manufacturers, then retail and food workers. Now, it’s Lyft drivers and Instacart workers – jobs that certainly harken back to that previous age, but with a few notable exceptions.

The most notable is that, for the first time ever, the working class has some level of flexibility. Especially during and before the Industrial Revolution, most workers worked 80+ hours a week, until the day they died. The generation after invented retirement (working only until you were relatively close to dying), and the generation now involves a schedule with more leeway than most of the highest paying jobs just last generation. Of course a lot of that leeway is somewhat farcical based on how many hours you have to work as a Lyft driver to hit your wage goal, but it still is fairly impressive.

But it’s not just the working class who’s gotten a quality-of-life raise. Think about what Lyft drivers and Instacart workers were in the 90s – private valets and personal shoppers. Just not that long ago, these services were only affordable to the rich! Now, even a Lyft driver could get their own Lyft if they wanted to.

The source of this comes, of course, from the evolution in convenience. Or logistics, which is sort of just more specified convenience. Our ability to make things cheaper, better, and faster has a big effect on our quality of life and in an economic sense this is certainly no exception. I wonder, what will the next generation’s working class look like?

July 11, 2022

Being Wise and Being Smart

Some people think that intelligence and wisdom are synonyms. In this article I’m going to explain why that’s not the case, as well as break down some other forms of smarts.

I’m sure you’ve met an arrogant smart person before. A person who always acts like they’re right, and – the worst part – they usually are. These people are naturally not very likable. I would argue that these people fit the notion of intelligence, but not wisdom. What they have in hard skills (knowledge) they lack in soft skills (communication). A wise person usually has both of these, which is what makes gaining wisdom harder than gaining intellect.

There is, of course, the question of how someone becomes wise in the first place. A lot of people correlate wisdom with age, but I’ve met enough downright awful old people to know that’s not the case. Rather, I think being wise has to do with the much more difficult balance of emotional intelligence and rational intelligence. A person who can be smart, yet at the same time be empathetic and understand there are things in this world they can’t understand.

There are other types of smarts worth knowing, too. Street smarts, for example, are fundamentally different from rational and emotional intelligence. Street intelligence requires cunning, cleverness, and charisma, skills that someone who is smart or wise might not necessarily have. I think these three, put together – emotion, rationality, and charisma – represent the three “base traits” that revolve around intelligence.

This is, of course, also partially the reason why IQ is so hard to reasonably measure. I’ve written about this before, and still stand by the idea that IQ cannot be accurately determined based on how much we currently know about it. This is one of the reasons why.