Peter Smith's Blog, page 80

September 29, 2017

MA Scholarship in Logic/Phil Math (Montreal)

Ulf Hlobil writes: “At Concordia University (Montreal), we want to do something about the gender imbalance in philosophy. We offer specialized scholarships for female international students who are working ancient philosophy or logic and philosophy of mathematics. Each scholarship is worth $32,450 CAD; up to two are awarded each year. We are currently inviting applications. Perhaps this may be of interest to your readers at Logic Matters.” Details are here.

September 28, 2017

The Great Formal Machinery Works

I’d like to have had the time now to carefully read Jan von Plato’s new book and comment on it here, as the bits I’ve dipped into are very interesting. But, after a holiday break, I must get my nose back down to the grindstone and press on with revising my own logic book.

I’d like to have had the time now to carefully read Jan von Plato’s new book and comment on it here, as the bits I’ve dipped into are very interesting. But, after a holiday break, I must get my nose back down to the grindstone and press on with revising my own logic book.

So, for the moment, just a brief note to flag up the existence of this book, in case you haven’t seen it advertised. Von Plato’s aim is to trace something of the history of theories of deduction (and, to a lesser extent, of theories of computation). After ‘The Ancient Tradition’ there follow chapters on ‘The Emergence of Foundational Studies’ (Grassman, Peano), ‘The Algebraic Tradition of Logic’, and on Frege and on Russell. There then follow chapters on ‘The Point of Constructivity’ (Finitism, Wittgenstein, intuitionism), ‘The Göttingers’ (around and about Hibert’s programme), Gödel, and finally two particularly interesting chapters on Gentzen (on his logical calculi and on the significance of his consistency proof).

This isn’t a methodical tramp through the history: it is partial and opinionated, highlighting various themes that have caught von Plato’s interest. And it’s all the better for that. The book retains the flavour of a thought-provoking and engaging lecture course, which makes for readability. It has been elegantly and relatively inexpensively produced by Princeton UP: you’ll certainly want to make sure your university library has a copy.

September 27, 2017

Postcard from the Lake District

After a week in the Lakes, here’s a photo taken walking back from Howtown to Pooley Bridge above Ullswater. Beautiful. Worries about Trump, Brexit, and even Begriffsschrift seem happily remote.

After a week in the Lakes, here’s a photo taken walking back from Howtown to Pooley Bridge above Ullswater. Beautiful. Worries about Trump, Brexit, and even Begriffsschrift seem happily remote.

August 14, 2017

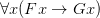

Begriffsschrift and absolutely unrestricted quantification

We owe to Frege in Begriffsschrift our modern practice of taking unrestricted quantification (in one sense) as basic. I mean, he taught us how to rephrase restricted quantifications by using unrestricted quantifiers plus connectives in the now familiar way, so that e.g. “Every F is G” is regimented as “Everything is such that, if it is F, then it is G” , and some “Some F is G” is regimented as “Something is such that it is F and it is G” — with the quantifier prefix in each case now running over everything. And we think the gain in formal simplicity in working with unrestricted quantifiers outweighs the small departure from the logical forms of natural language (and quirks to do with existential import, etc.).

But what counts as the “everything” which our unrestricted quantifiers run over? In informal discourse, we cheerfully let the current domain of quantification be set by context (“I’ve packed everything”, “Everyone is now here, so we can begin”). And we are adepts at following conversational exchanges where the domain shifts as we go along.

In the context of using a formal first-order language, we require that the domain, i.e. what counts as “everything”, is fixed once and for all, up front: no shifts are then allowed, at least while that language with that interpretation is in force. All changes of what we want to generalize about are to be made by explicitly restricting the complex predicates our quantifiers apply to, as Frege taught us. The quantifiers themselves stay unrestrictedly about the whole domain

What about Frege in Begriffsschrift, however? There’s nothing there explicit about domains. Is that because he thinks that the quantifiers are always to be taken as ranging, not over this or that domain, but over absolutely everything — over all objects that there are?

Some have taken this to be Frege’s view. In particular, when Dummett talks about Frege and unrestricted quantification in Frege: Philosophy of Language, he is firmly of the view that “When these individual variables are those of Frege’s symbolic language, then their domain is to be taken as simply the totality of all objects” (p. 529).

But it isn’t obvious to me that Frege is committed to an idea of absolutely general quantification, at least in Begriffsschrift. (Re)reading the appropriate bits of that book plus the two other contemporary pieces published in Bynum’s Conceptual Notation, and the two contemporary pieces in Posthumous Writings, there doesn’t seem to be a clear commitment to the view.

OK, Frege will write variations on: “ ” means that whatever you put in place of the “

” means that whatever you put in place of the “ ”, “

”, “ ” is correct. But note that here he never gives daft instantiations of the variable, totally inappropriate to the e.g. arithmetic meaning of F and G.

” is correct. But note that here he never gives daft instantiations of the variable, totally inappropriate to the e.g. arithmetic meaning of F and G.

This is not quite his example, but he does the equivalent of remarking that “ is even

is even  is even)” isn’t refuted by “

is even)” isn’t refuted by “ ” because (given the truth-table for “

” because (given the truth-table for “ ”), that comes out true. But he never, as he should if the quantifiers are truly absolutely unrestricted, consider instances such as “The Eiffel Tower is even

”), that comes out true. But he never, as he should if the quantifiers are truly absolutely unrestricted, consider instances such as “The Eiffel Tower is even  The Eiffel Towe

The Eiffel Towe is even” — which indeed is problematic as the consequent looks nonsense. (Has Frege committed himself in Begriffsschrift to the view that every function is defined for the whole universe?)

is even” — which indeed is problematic as the consequent looks nonsense. (Has Frege committed himself in Begriffsschrift to the view that every function is defined for the whole universe?)

Similarly, in PW, p. 27, Frege cheerfully writes “The numbers … are subject to no conditions other than  , etc.”. There’s not a flicker of concern here about instances — as they would be if the implicit quantifier here were truly universal — such as “

, etc.”. There’s not a flicker of concern here about instances — as they would be if the implicit quantifier here were truly universal — such as “ ”. Rather it seems clear that here Frege’s quantifiers are intended to be running over … numbers!

”. Rather it seems clear that here Frege’s quantifiers are intended to be running over … numbers!

(As a diverting aside, note that even if Frege had committed himself to the view that every function is defined for the whole universe by giving a default value to  when one at least of X, Y is non-arithmetic, that really wouldn’t help here. For then

when one at least of X, Y is non-arithmetic, that really wouldn’t help here. For then  taken as a quantification over everything would imply

taken as a quantification over everything would imply  and

and  and hence — since the right-hand sides take the default value–

and hence — since the right-hand sides take the default value–  .)

.)

Earlier in PW, p. 13, Frege talks about the concept script “supplementing the signs of mathematics with a formal element” to replace verbal language. And this connects with what has always struck me as one way of reading Begriffsschrift.

Yes it is all purpose, in that the logical apparatus can be added to any suitable base language (the signs of mathematics, the signs of chemistry, etc. and as we get cleverer and unify more science, some more inclusive languages too). And then too we have the resources to do conceptual analysis using that apparatus (e.g. replace informal mathematical notions with precisely defined versions) — making it indeed a concept-script. But what the quantifiers, in any particular application, quantify over will depend on what the original language aimed to be about: for the original language of arithmetic or chemistry or whatever already had messy vernacular expressions of generality, which we are in the course of replacing by the concept script.

Yes, the quantifiers will then unrestrictedly quantify over all numbers, or all chemical whatnots, or …, whichever objects the base language from which we start aims to be about (or as we unify science, some more inclusive domain set by more inclusive language).

And yes, Frege’s explanation of the quantifiers — for the reasons Dummett spells out — requires us to have a realist conception of objects (from whichever domain) as objects which determinately satisfy or don’t satisfy a given predicate, even if we have no constructive way of identifying each particular object or of deciding which predicates they satisfy. Etc.

But the crucial Fregean ingredients (1) to (3) don’t add up to any kind of commitment to conceiving of the formalised quantifiers as absolutely unrestricted. He is, to be sure, inexplicit here — but it not obvious to me that a charitable reading of Begriffsschrift at any rate has to have Frege as treating his quantifiers as absolutely unrestricted.

July 31, 2017

July 25, 2017

Spam, spam, spam, spam, …

[Reposted/updated from thirty months ago.] There are only two options for any blog. Allow no comments at all; or have a spam-filter that filters what goes into the moderation queue. No way can you moderate by hand all the comments that arrive. For example, since I moved this blog to use WordPress — reports the plug-in at LogicMatters — there have been almost half a million(!) spam postings in the comments here filtered out by Akismet so that I never even see them, never have to deal with them.

Akismet does a quite brilliant job, then. I’m certainly not going to turn it off! But it can occasionally err on the side of sternness. If you try to make a sensible comment here which never gets approved, then it may not be me being unfriendly! If your words of wisdom seem unappreciated, you can always try re-sending them as an email. (If you have had a comment approved before, however, then you should be able to comment without waiting for moderation.)

July 23, 2017

Which is the quantifier?

A note on another of those bits of really elementary logic you don’t (re)think about from one year to the next – except when you are (re)writing an introductory text! This time, the question is which is the quantifier, ‘ ’ or ‘

’ or ‘ ’, ‘

’, ‘ ’ or ‘

’ or ‘ ’? Really exciting, eh?

’? Really exciting, eh?

Those among textbook writers calling the quantifier-symbols  ’, ‘

’, ‘ ’ by themselves the quantifiers include Barwise/Etchemendy (I’m not sure how rigorously they stick to this, though). Tennant also calls e.g. ‘

’ by themselves the quantifiers include Barwise/Etchemendy (I’m not sure how rigorously they stick to this, though). Tennant also calls e.g. ‘ ’ a quantifier, and refers to ‘

’ a quantifier, and refers to ‘ ’ as a quantifier prefix.

’ as a quantifier prefix.

Those calling the quantifier-symbol-plus-variable the quantifier include Bergmann/Moor/Nelson, Chiswell/Hodges, Guttenplan, Jeffrey, Lemmon, Quine, Simpson, N. Smith, P. Smith, Teller, and Thomason. (Lemmon and Quine of course use the old notation ‘ ’ for the universal quantifier.) Van Dalen starts by referring to ‘

’ for the universal quantifier.) Van Dalen starts by referring to ‘ ’ as the quantifier, but slips later into referring to ‘

’ as the quantifier, but slips later into referring to ‘ ’ as the quantifiers.

’ as the quantifiers.

It’s clear what the majority practice is. Why not just go with it?

Modern practice is to parse ‘ ’ as ‘

’ as ‘ ’ applied to ‘

’ applied to ‘ ’. However Frege (I’m reading through Dummett’s eyes, but I think this is right, mutating the necessary mutanda to allow for differences in notation) parses this as the operator we might temporarily symbolize ‘

’. However Frege (I’m reading through Dummett’s eyes, but I think this is right, mutating the necessary mutanda to allow for differences in notation) parses this as the operator we might temporarily symbolize ‘ ’ applied to ‘

’ applied to ‘ ’.

’.

To explain: Frege discerns in ‘ ’ the complex predicate ‘

’ the complex predicate ‘ ’ (what you get by starting from ‘

’ (what you get by starting from ‘ ’ and removing the name). Generalizing involves applying an operator to this complex predicate (it really is an ‘open sentence’ not in the sense of containing free variables but in containing gaps — it is unsaturated). Another way of putting it: for a Fregean, quantifying in is a single operation of taking something of syntactic category s/n, and forming a sentence by applying a single operation of category s/(s/n). This quantifying operator is expressed by filling-the-gaps-with-a-variable-and-prefixing-by- ‘

’ and removing the name). Generalizing involves applying an operator to this complex predicate (it really is an ‘open sentence’ not in the sense of containing free variables but in containing gaps — it is unsaturated). Another way of putting it: for a Fregean, quantifying in is a single operation of taking something of syntactic category s/n, and forming a sentence by applying a single operation of category s/(s/n). This quantifying operator is expressed by filling-the-gaps-with-a-variable-and-prefixing-by- ‘ ’ in one go, so to speak. The semantically significally widget here is thus ‘

’ in one go, so to speak. The semantically significally widget here is thus ‘ ’. Yes, within that, ‘

’. Yes, within that, ‘ ’ is a semantically significant part (it tells us which kind of quantification is being done). But — the Fregean story will go — ‘

’ is a semantically significant part (it tells us which kind of quantification is being done). But — the Fregean story will go — ‘ ’ is not a semantically significant unit.

’ is not a semantically significant unit.

So, whether you think ‘ ’ is worthy of being called the universal quantifier is actually not such a trivial matter after all. For is ‘

’ is worthy of being called the universal quantifier is actually not such a trivial matter after all. For is ‘ ’ a semantically significant unit? You might think that the true believing Fregean protests about this sort of thing too much. I’d disagree — but at any rate the underlying issue is surely not just to be waved away by unargued terminological fiat.

’ a semantically significant unit? You might think that the true believing Fregean protests about this sort of thing too much. I’d disagree — but at any rate the underlying issue is surely not just to be waved away by unargued terminological fiat.

July 22, 2017

Ivana Gavrić, Chopin

I’ve very much admired Ivana Gavrić previous rightly praised discs (I wrote about the first two here in an earlier post, and you can find more about them here). So I was really looking forward to hearing her play in the intimate surroundings of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge a few days ago; but she had to postpone the concert as she can’t fly at the moment on doctor’s orders.

I’ve very much admired Ivana Gavrić previous rightly praised discs (I wrote about the first two here in an earlier post, and you can find more about them here). So I was really looking forward to hearing her play in the intimate surroundings of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge a few days ago; but she had to postpone the concert as she can’t fly at the moment on doctor’s orders.

So to make up for that, I bought a copy of her new Chopin CD, which I have been listening to repeatedly over the last few days. Now, I should say that I’m not the greatest Chopin devotee, and indeed the only recording of his music that I have returned to at all frequently in recent years has been Maria João Pires’s utterly wonderful performances of the Nocturnes. So I’m hardly in a position to give a very nuanced response to this new disc. But I am loving it.

Ivana Gavrić plays groups of Chopin’s earlier Mazurkas, seperated by a couple of Preludes, a Nocturne and the Berceuse, which makes for something like a concert programme (you should listen up to the Berceuse — which is quite hauntingly played, her left hand rocking the cradle in a way that somehow catches at the heart — and then take an interval!). Some of the Mazurkas are very familiar, but many are (as good as) new to me. The Gramophone reviewer wanted Gavrić to perhaps play with more abandon — but no, her unshowy, undeclamatory, playing seems just entirely appropriate to the scale and atmosphere of the pieces, often tinged with melacholy as they are. She is across the room from a group of you, friends and family perhaps, rather than performing to a concert hall. And repeated listenings reveal the subtle gestures and changes in tone she uses to shape the dances; these are wonderfully thought-through performances. Listen to the opening Mazurka in C sharp minor, Op. 6 no.2, and you will be captivated.

July 20, 2017

Why mandatory reiteration in Fitch-style proofs?

Digressing from issues about the choice of language(s), another post about principles for selecting among natural deduction systems — another choice point, and (though I suppose relatively minor) one not considered by Pelletier and Hazen.

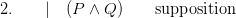

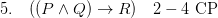

Take the most trite of examples. It’s agreed that if P then R. I need to convince someone that if P and Q then R (I’m dealing with a dullard here!). I patiently spell it out:

We are given if P then R. So just suppose that P and Q. Then of course P will be true, and hence (given what we agreed) R. So our supposition leads to R, OK? – hence as I said, if P and Q then R.

You want that set out more formally? Here goes, indenting sub-proofs Fitch-style!

Job done!

Except that in many official versions of Fitch-style proofs, this derivation is illegitimate. We can’t appeal to the initial premiss at (1) in order to draw the modus ponens inference inside the subproof: rather, we have to first re-iterate the premiss in the subproof, and then appeal to this reiterated conditional in applying modus ponens.

This requirement for explicit reiteration seems to go back to Jaśkowski’s first method of laying out proofs; and it is endorsed by Fitch’s crucial Symbolic Logic (1952). Here are some other texts using the same graphical layout as introduced by Fitch, and also requiring inferences in a subproof to appeal only to what’s in that subproof, so that we have to use a reiteration rule in order to pull in anything we need from outside the subproof: Thomason (1970), Simpson (1987/1999), Teller (1989).

Now, such a reiteration rule has to say what you can reiterate. For example: you can reiterate items that occur earlier outside the current subproof, so long as they do not appear in subproofs that have been closed off (and then, but only then, these reiterated items can be cited within the current subproof). But it is less complicated and seems more natural not to require wffs actually to be rewritten. The rule can then simply be: you can cite “from within a subproof, items that occur earlier outside the current subproof, so long as they do not appear in subproofs that have been closed off” — which is exactly how Barwise and Etchemendy (1991) put it. Others not requiring reiteration include Hurley (1982), Klenk (1983) and Gamut (1991). (Bergmann, Moor and Nelson (1980) have a rule they call reiteration, but they don’t require applying a reiteration rule before you can cite earlier wffs from outside a subproof.)

So: why require that you must, Fitch-style, reiterate-into-subproofs before you can cite e.g. an initial premiss? What do we gain by insisting that we repeat wffs within a subproof before using them in that subproof?

It might be said that, with the repetitions, the subproofs are proofs (if we treat the reiterated wffs as new premisses). But that’s not quite right as in a Fitch-style proof it is required that the premisses be listed up front, not entered ambulando. So we’d have to re-arrange subproofs with the new supposition and the reiterated wffs all up front: and no one insists that we do that.

Anyway: at the moment I’m not seeing any compelling advantage for going with Fitch/Thomason/Simpson/Teller rather than with Barwise and Etchemendy and many others. Going the second way keeps things snappier yet doesn’t seem any more likely to engender student mistakes, does it? But has anyone any arguments for sticking with a reiteration requirement?

Why reiteration in Fitch-style proofs?

Digressing from issues about the choice of language(s), another post about principles for selecting among natural deduction systems — another choice point, and (though I suppose relatively minor) one not considered by Pelletier and Hazen.

Take the most trite of examples. It’s agreed that if P then R. I need to convince someone that if P and Q then R (I’m dealing with a dullard here!). I patiently spell it out:

We are given if P then R. So just suppose that P and Q. Then of course P will be true, and hence (given what we agreed) R. So our supposition leads to R, OK? – hence as I said, if P and Q then R.

You want that set out more formally? Here goes, indenting sub-proofs Fitch-style!

Job done!

Except that in many official versions of Fitch-style proofs, this derivation is illegitimate. We can’t appeal to the initial premiss at (1) in order to draw the modus ponens inference inside the subproof: rather, we have to first re-iterate the premiss in the subproof, and then appeal to this reiterated conditional in applying modus ponens.

This requirement for explicit reiteration seems to go back to Jaśkowski’s first method of laying out proofs; and it is endorsed by Fitch’s crucial Symbolic Logic (1952). Here are some other texts using the same graphical layout as introduced by Fitch, and also requiring inferences in a subproof to appeal only to what’s in that subproof, so that we have to use a reiteration rule in order to pull in anything we need from outside the subproof: Thomason (1970), Simpson (1987/1999), Teller (1989).

Now, such a reiteration rule has to say what you can reiterate. For example: you can reiterate items that occur earlier outside the current subproof, so long as they do not appear in subproofs that have been closed off (and then, but only then, these reiterated items can be cited within the current subproof). But it is less complicated and seems more natural not to require wffs actually to be rewritten. The rule can then simply be: you can cite “from within a subproof, items that occur earlier outside the current subproof, so long as they do not appear in subproofs that have been closed off” — which is exactly how Barwise and Etchemendy (1991) put it. Others not requiring reiteration include Hurley (1982), Klenk (1983) and Gamut (1991). (Bergmann, Moor and Nelson (1980) have a rule they call reiteration, but that’s for re-iterating within a level of proof, and they don’t require applying a reiteration rule before you can cite earlier wffs from outside a subproof.)

So: why require a Fitch-style reiteration-into-subproofs rule? What do we gain by insisting that we repeat wffs within a subproof before using them in that subproof?

It might be said that, with the repetitions, the subproofs are proofs (if we treat the reiterated wffs as new premisses). But that’s not quite right as in a Fitch-style proof it is required that the premisses be listed up front, not entered ambulando. So we’d have to re-arrange subproofs with the new supposition and the reiterated wffs all up front: and no one insists that we do that.

Anyway: at the moment I’m not seeing any compelling advantage for going with Fitch/Thomason/Simpson/Teller rather than with Barwise and Etchemendy and many others. Going the second way keeps things snappier yet doesn’t seem any more likely to engender student mistakes, does it? But has anyone any arguments for sticking with a reiteration rule?