Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 967

August 16, 2012

Actress Carmen Egojo Talks 'Sparkle' and Her Character 'Sister'

Reel Black

900 AM WURD's Mid Morning Mojo Host Stephanie Renee sat down with actress Carmen Egojo (Boycott, Alex Cross) to discuss her role in the remake of Sparkle in this exclusive clip.

Published on August 16, 2012 08:30

August 15, 2012

Black (Collaborative) Genius: Some Thoughts on the Nas ‘Ghostwriter’ Controversy

Black (Collaborative) Genius:

Some Thoughts on the Nas ‘Ghostwriter’ Controversy by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The recent “ghostwriter” controversy regarding Nasir Jones and his 2008 untitled album, has less to do with questions about authorship and authenticity, but is rather a product of a generations of Americans so enveloped in their insecurities and tethered to a relentless individualism, that they see little value in the collaborative spirit. The irony of those who might deny Jones his legitimate claim on artistic genius is that the very traditions of Black expressive culture that he has so brilliantly upheld throughout his career is rooted in collaboration.

“Strange Fruit” is generally regarded as one of the most important protest songs of the 20th century, and the song has long been associated with Billie Holiday, who first recorded the soon in 1939. Given the history of violence against African American and the trauma that Holiday often had to transcend throughout her life, it is rather easy to believe that Holiday was the “author” of the song. “Strange Fruit” was written by a Jewish school teacher from the Bronx named Abel Meeropol (his pen name was Lewis Allan), and that fact does nothing detract from the fact that when Holiday opened her mouth and performed the song, it was indeed her song.

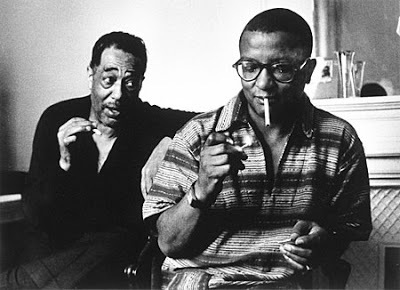

What the most brilliant artists understand is that there are, in fact, limits to their creativity, and they are secure enough in their talents, that they are more than willing to reach out to artistic collaborators that could help them better realize their artistic ideas. One great example of this is Duke Ellington, arguably most important American composer of the 20thcentury. Though Ellington was a gifted pianist in his own right, he needed musicians like saxophonists Ben Webster and Johnny Hodges to help him fully realized his sound. Indeed Ellington’s most notable collaborator, Billy Strayhorn (who was an out gay man in the Jazz world) was responsible for many signature Ellington songs like “Take the A Train,” “Lush Life” and “Satin Doll.”

Even James Brown, who is singularly credited with creating Funk and providing the most important musical building blocks for rap music, would have had little impact on American music without collaborators like Fred Wesley and Pee Wee Ellis. Brown had a head full of intricate rhythms, but without the ability to read or write music, he absolutely needed Wesley (who was classically trained” and Ellis to help transcribe the ideas he had in his head into musical notations that his band could learn. Without Wesley and Ellis, Brown would have simply been another angry black man looking for an outlet to express the rage, pain and desire trapped in his head (remember Nick Cannon’s character from Drumline? ).

In some cases some Black musical geniuses were incapacitated without the use of collaborators. Every one of Marvin Gaye’s recordings from his mature era where the product of collaborations: for What’s Going On it was musicians Elgie Stover, James Nix, Al Benson and his wife Anna Gordy Gaye; on Let’s Get it On, Gaye collaborated with Ed Townsend; when Gaye returned to the studio to record I Want You it was the hot young songwriter Leon Ware who helped him crystallize his ideas. When Gaye was without collaborators, he didn’t work, yet no one would think to diminish his genius because of it. Ask Stevie Wonder what his great output in the 1970s might have been like without Tonto’s Expanding Head Band—the duo of Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil—who created the Moog machine that fundamentally changed how Wonder imagined his music.

In a telling response about the ghostwriter controversy Dead Prez’s Stic.man wrote on his Facebookpage “My contributions to his album was a collaboration and an honor and under his direction of what he wanted to convey and say.” As the tradition goes, that’s par for the course,

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books including the forthcoming Looking For Leroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities (New York University Press). He is professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African & African-American Studies at Duke University and the host of the Weekly Webcast Left of Black . Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan.

Published on August 15, 2012 18:51

Michael Grunwald Author of 'The New New Deal': "Obama Stimulus Purest Distillation of Change"

Published on August 15, 2012 09:08

Media Literacy 101: WBBM (CBS) Criminalize 4-Year-old Child

bobbutler7 (Maynard Institute): CBS Television Station WBBM in Chicago is being criticized for airing a misleading the video of a 4-year old boy saying he wanted a gun. The boy made the comment, after being asked loaded questions by a freelance photographer, because he wanted to be a police officer.

The Society of Professional Journalists says the decision to edit the video "reveals a lack of understanding of the very basic tenets of journalism."

Published on August 15, 2012 08:37

August 14, 2012

Blaming Hip-Hop for Hate Rock?

Blaming Hip-Hop for Hate Rock?David J. Leonard & C. Richard King | NewBlackMan (in Exile) Little says more about the state of racism and the centrality of the white racial frame in the USA today than the rapidity with which pundits transformed a conversation about white power, racialized violence, and hate rock into a critique of hip-hop. Indeed, a number of discussions of the spree killing at the Sikh temple outside of Milwaukee, echoing broader political currents, reference the evils of hip-hop as both a defense and a scapegoat.

Perhaps not surprisingly, in The New Republic, John McWhorter rehearsed this well worn conversation to turn the killings into another referendum on hip-hop. “It has been fashionable,” he asserts, “to speculate on whether the White Power music he [Wade Michael Page] listened to helped stoke him into the senseless murders he committed...such speculations,” he suggests are both “incoherent” and “pointless—and they are marked, above all, by a cloying air of self-congratulation.” To “prove” his point, he invoked the tried and tested “hip-hop” comparison as if it represented mainstream rap, failing to note, of course, that he is specifically talking about a small subset of hip-hop music):

A comparison with another musical genre helps put the debate into relief. Indeed, in assessing White Power music’s influence on Page, it helps to acknowledge that rap music—savored by people of all colors, ranging in age from “youth” to middle-aged—has its own tendency to celebrate the indefensible. Some practitioners casually boast about hurting women—whether attacking a partner during intercourse (Cam’ron, “Boy, Boy”), or kicking a woman in the stomach to make her abort (Joe Budden, “Confessions II”) and, of course, all varieties of maiming and murder.

However, nasty as all of this is, and whatever one might say about its implications for the street culture that produced it, it’s all symptom rather than cause. Those who listen to rap—including myself—are not passively consuming its message, but actively seeking it as a release. Indeed, last I heard, the enlightened take on rap lyrics is that their violence must be taken not as counsel but as poetry, poses of strength from disenfranchised people—“Black Noise” as Brown’s Tricia Rose calls it. Other academics, priding themselves on their connection with the music, crown the makers of violent rap as “Prophets of the Hood” (Imani Perry, Princeton) or “Hoodlums” (William Van Deburg, University of Wisconsin), the latter meant as an arch compliment to men celebrated for speaking truth to power.

And there is more than a little bit of truth to this treatment of rap’s violent strain. It is, indeed, an attitude that functions as a response to the frustrations of everyday life. In that light, rapademics have been fond of noting that old-time “toasts” among black people had their violent strains as well. Despite the prevalent anxieties in the 1990s about the social consequences of rap music, evidence that the music causes actual violence never actually surfaced.

These arguments are as tired as they are simplistic; the failure to see any difference between rap music and hate rock is absurd on every level. Yet, they keep getting published. Yet another failure to account for white supremacy. Importantly, invoking the purported ills associated hip hop simultaneously recycles dangerous stereotypes about blacks and lets whites off the hook. Indeed, it encourages white readers to misrecognize the force of white racism and dissociate themselves from deeper structural arrangements, while essentially giving a pass to the violence, antipathy, and dehumanization at the core of white power music specifically, and white powerthinking more generally. It is as if McWhorter would like to conclude: there are haters everywhere, stop picking on isolated whites who do bad things and pay attention to the ubiquitous threat of black pathology.

Responding to the work of Robert Futrell and Pete Simi, whose analysis of “spaces of hate” offers an important context for understanding Wade Michael Page, Cord Jefferson writes an apologia for hate rock. His “In Defense of Neo-Nazi Music,” a title which summarizes the security and vulgarity of white supremacy today, dismisses any focus on his relationship to music as akin to those who blame video games or rock music for violence:

People like Futrell and Simi try to avoid sounding like the neo-Tipper Gores that they are by not condemning the neo-Nazi music itself and instead saying that it's the culture around the music that's dangerous. It's the "spaces of hate" they're after, they say, not the art. But then they expose their anti-free speech leanings by finger-wagging and threatening that we shouldn't be surprised if another white-power maniac kills people thanks to this hateful music scene. That—and I'm so glad I work at Gawker now so I can say this—is a total crock of shit.

To follow Futrell and Simi's logic, let's fight drug culture by cancelling the Electric Daisy Carnival, a massive electronic music festival that's become as synonymous with MDMA as it has dubstep. Let's also cut down on drunk driving by banning football games, at which tailgaters young and old get blotto all day before getting in their SUVs and driving home. And, of course, let's eliminate violence in the inner city by totally banishing hip-hop from our nation, which, as Tipper and her ilk argued for years, is the real reason young black men kill each other at heartbreaking rates.

In such analysis, history and context do not matter; ideology has no connection to action. In Jefferson’s world, we are all the same, all equal, all individuals who have free will to act of our own accord without reference to social location, dominant frames, or the burdens of the past. Such free agents animate the new racism of 21st century America, mobilizing white privilege under the cover of abstract liberalism and individual liberty.

Responding to some comments from readers, Jefferson invoked hip-hop as part of the defense of his defense of hate music.

I can see where you're coming from to a degree, but I worry that it's splitting hairs. I'm almost positive that there are people in this world who have listened to NWA's "Fuck the Police" or Ice-T's "Cop Killer" and later attacked cops, and those are only the songs that really go in on police. Dozens—perhaps hundreds—of other rap songs either lightheartedly disparage cops or outright fantasize about cops getting killed. If we're talking about fictional distance, you run into a problem when it comes to hip-hop and the police force. The same goes for hip-hop and misogyny.

In other words, it's as if rap music isn’t blamed for violence against the police, which it has been, and one familiar with Tipper Gore (to take one example he himself invokes) should know this. And more, if many people can listen to it without engaging in violence, then the music is irrelevant, which again runs selectively counter to the demonization of blackness and hip hop.

Revealing a lack of understanding of the role of hate rock and other forms of white nationalist popular culture in terms of recruitment, identity formation, and in the formation of an imagined community, Jefferson replicates the narrative that hate rock is just music; forgetting or not knowing that centrality of white racism to the development of popular music over the past century, to the cultivation of taste, to the creation of styles and audiences, to the production of objects of adoration, consumption, and identification. Clearly hip-hop music or action films don’t foster identity, community, and a sense of belonging based on violence, a sense of superiority, and a culture/ideology based in hate.

There is much to be critical about in terms of some rap music, some action films, some video games, but none of them compare to the soundtrack to white supremacy. Different game . . . different planet . . . different reality. Do these genres of popular culture function as propaganda? Do they produce revenue for organizations committed to white nationalism, retrograde racial politics, and even the coming race war? Do they play a leading and self-conscious role in the recruitment of youth to advance these projects? Efforts to reimagine hate rock as simply popular culture, applying the debates commonplace to the culture wars and ubiquitous in regards to the first amendment, fails to see how this music (as with other forms of white-nationalist produced popular culture) operates as propaganda, as an assault on truth. Maybe Cord Jefferson and others needs to crack open history books to truly understand the music. In Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbels, who was the Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, initiated “synchronization of culture, by which the arts were brought in line with Nazi goals.” Was this just popular culture; was opposition to their propaganda akin to Tipper Gore? Was the Nazi’s party use of newspapers and film simply a cultural production (see here for examples)? I wonder if those who dismiss any discussion of the music, of the video games produced by white supremacist, of the various videos, would be so quick to dismiss the posters of Nazi Germany or the ways that Al Qaeda has used video games? Would the discussion be “did these posters or video games” cause terrorism? Why are we not examining the ways that white supremacists use the music to recruit, to disseminate a worldview based in violence, hate, and white supremacy?

Yet, Jefferson and McWhorter trot out the same old tired arguments about free speech, about the number of individuals who have listened to the music without committing violence, and how there is no casual proof. He might as well have argued that guns don’t kill people, music doesn’t kill people, bad people kill people:

Because the truth is that thousands and thousands of people just like Wade Page have for decades been listening to the same kind of hatecore he enjoyed, and yet very few of them have done what he did. In the same vein, neither will most Marilyn Manson fans go on a shooting rampage like that of his late fans Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who executed a host of their classmates at Columbine High School.

Over the past few days, Wade Page's friends and family have shed some light on his recent history: Page was an alcoholic who was discharged from the military in 2001 for showing up to a formation drunk. He was then fired from a trucking job in 2010 because got arrested for a DUI. After that, he found work hard to come by, and the bank foreclosed on his house in January of this year. By then he was 40 and living with money, no job, no family, and few ways to escape his alcoholic haze. It would certainly be tidy to say that the music made Page do it, but that neglects to acknowledge that hate, rage, and the eagerness to implode are also emotions every broke alcoholic probably feels, neo-Nazi or no. Interestingly, End Apathy put out one record before Page died. It was called Self Destruct.

The failure of people to look at the ideology, at grammar, and the message within hate rock is revealing. The discussion cannot and shouldn't just be about does "hate music" lead to violence? White supremacy leads to the violence; it leads to the music; it leads to video games from white nationalists that encourage players to take pleasure in killing people of color. The discussion needs to be about how the music contributes to a worldview, how to represents an epistemological challenge to truth, how the music reifies a belief that whites are victims, that civilization is under attack. It is propaganda and therefore it is important to examine how it compels action, how it dehumanizes people of color, how it solidifies bonds within white nationalist communities through construction of the Other, and how it other spreads a narrative of white victimhood, dangerous criminals of color, threatening Jews, and a society that is increasingly inhospitable to white America.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. Leonard’s latest book After Artest: Race and the Assault on Blackness was just published by SUNY Press in May of 2012.

C. Richard King is Professor of Ethnic Studies at Washington State University at Pullman and the author/editor of several books, including Team Spirits: The Native American Mascot Controversy and Postcolonial America.

Published on August 14, 2012 13:17

Remembering Whitney, Never Forgetting Nippy, and Waiting for Sparkle

Remembering Whitney, Never Forgetting Nippy, and Waiting for Sparkle by Nicole Moore | HuffPost BlackVoices

This past Thursday would have been Whitney Houston's 49th birthday and I still cannot wrap my mind around the fact that she is dead. Six months after her shocking death and her passing feels as sudden and as unreal now as it did that day in February when she drowned in her Beverly Hilton Hotel bathtub. Unlike Michael Jackson's death where many of us felt like we somehow had let the King of Pop slip through our brown fingers, with Whitney we felt, ahem, feel, robbed. Like someone snatched our sister right from our clutches in broad daylight.

I, like many of you, had seen the interview with Shaun Robinson of Access Hollywood on the set of Sparkle and Whitney looked amazing. Sparkle, a film that Whitney executive produced, was going to be a reintroduction for the most awarded singer of all time to a younger generation and her coming-out party to all the rest of us who grew-up with her. It was especially exciting for Black folk because Sparkle, with its almost all-Black cast is a movie for us to not only see Whitney, but it's the kind of film where we know we will also catch glimpses of Nippy.

Nippy was the woman we saw in 2010 receiving a BET Honorsaward, running to the stage to high-five her best friend Kim Burrell who sang in tribute to her. She was the woman who portrayed a mouthy, ambitious yet naïve Savannah in Waiting To Exhale. She was also, and most unfortunately, the woman we saw on Being Bobby Brown, and Nippy was the one who struggled with addiction and wound up in that bathtub, inebriated, listening to gospel music and nodding off to rest forever.

What I found so incredibly fascinating, indeed appealing about Whitney was her ability to be America's girl-next-door while also being our around-the-way-homegirl. Just when we thought she was getting "too pop," she'd talk about needing to finish an interview so she could go to Roscoe's for some fried chicken or she'd switch wigs- from long, blond, and curly to a short, dark brown bob. She was a chameleon. She was their Whitney, but she was our Nippy. On stage she'd sing pop candy tunes like "I Wanna Dance With Somebody," "My Name Is Not Susan" and "Where Do Broken Hearts Go" with the kind of angelic middle-American sweetness that melts sugar into caramel goodness. But we also knew she was from Newark, smoked Newports and would curse you out in a nanosecond if she felt like you were trying to play her.

And Whitney's shifts in demeanor may have looked like bouts of inauthenticity to some, but I recognized the power she harnessed by flipping her camouflage depending on her surroundings. In high school, my friends and I did it all the time. We'd talk "proper" in class with our teachers and to some of our white classmates depending on their flow, but once in the schoolyard or back home on our block we'd "cut up." And I'll never forget while in college not discovering a friend was Jamaican for two months until Parents Weekend and hearing her speak to her folks. All of a sudden her voice had this beautiful and distinct lilt. It was like night and day. It was canoodling with Kevin Costner on the big screen and tonguing-down Bobby Brown on the small screen.

Truly having Sparkle as her farewell nod is a wonderfully sad irony. She plays Emma-- a single mother, former singer and now devout Christian dealing with the aspirations, challenges and growing pains of her three teenage daughters who want to be big-time singers. Living in Detroit during the Motown era her three girls, including Sparkle played by American Idol sweetheart Jordin Sparks, go through the ups and downs of love, addiction, and success with the their mom who is conflicted by her past mistakes, but also convicted with the love only a mother can have for daughters. For better and for worse she sees herself in them.

I wonder how much of her daughter's aspirations, passions and struggles did Whitney see in those three girls. Would she have supported Bobbi Kristina's reality show dreams? How much of Nippy did she see in Emma's missteps? And how tired she must've been trying to negotiate the pop media darling who was to appear that night at Clive's Grammy party with the woman who just wanted to listen to Fred Hammonds, high-five and cut-up with her homegirls, and have her daughter be all that she wants to be. Surely she was exhausted. Peace Nip, you're finally at rest.

***

Nicole is the Founder and Editor of theHotness.com . theHotness is now an international destination for women who desire more from their media sources than mascara tips and celebrity gossip to empower and entertain. Nicole’s writing has been featured on TheRoot.com, VOGUE_Black.it, and in The Village Voice, Heart & Soul, Essence and Uptown magazines.

Follow Nicole Moore on Twitter: www.twitter.com/thehotnessgrrrl

Published on August 14, 2012 12:42

August 13, 2012

Trailer—‘Searching for Sugar Man’ (dir. Malik Bendjelloul)

SONY Pictures Classics:

This award-winning documentary charts the extraordinary and inspirational story of mysterious 1970s musician Rodriguez.

In the late '60s, a musician was discovered in a Detroit bar by two celebrated producers who were struck by his soulful melodies and prophetic lyrics. They recorded an album that they believed was going to secure his reputation as one of the greatest recording artists of his generation. In fact, the album bombed and the singer disappeared into obscurity amid rumors of a gruesome on-stage suicide. But a bootleg recording found its way into apartheid South Africa and, over the next two decades, it became a phenomenon. Two South African fans then set out to find out what really happened to their hero. Their investigation led them to a story more extraordinary than any of the existing myths about the artist known as Rodriguez. This is a film about hope, inspiration and the resonating power of music.

Published on August 13, 2012 20:21

Bling47 Breaks—Dilla Edition: Mos Def—“History” (feat Talib Kweli)

Bling47 Breaks:

My convo got heavy with Rich Medina as we spoke about how Dilla’s sound changed in his latter years. There were some strong points made on both sides. That said, we touched on Jay’s chop of Mary Wells, “Two Lovers History”.

Published on August 13, 2012 19:36

US Teens Stuggle to Find Work

Al Jazeera English

Teenagers compete with out of work adults for jobs in the worst job market the United States has seen since the Second World War.

Al Jazeera's Cath Turner has more.

Published on August 13, 2012 13:31

Bomani Jones: London's 2012 Olympics Need a Nickname

SBNation:

Before we pack the Summer Olympics away, Bomani & Jones has a few suggestions for what to name these 2012 Olympics. Bolt was the star, Lolo was too big a story (ditto Gabby's hair), and somehow nut-punching was deemed more "in the Olympic spirit" than badminton position jockeying. But the big winner? Dominique Dawes, who trumped gold with diamond.

Published on August 13, 2012 13:23

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.