Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 963

August 28, 2012

White Denial and Black Middle-Class Reality - Part 2

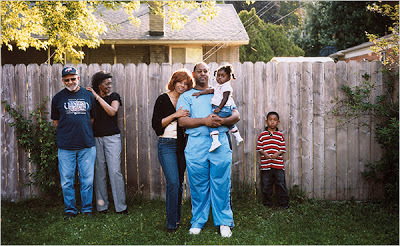

Damon Winter/The New York Times

Damon Winter/The New York Times White Denial and Black Middle-Class Reality - Part 2 by David J. Leonard | HuffPost BlackVoices

Denial is a fixture of contemporary racial discourse. Reflecting segregation and the entrenched nature of white privilege, the efforts to deny through citing a mythical black middle-class, as if the black middle-class reveals some post-racial reality, defies the facts on the ground. It defies the realities of America's housing situation.

Housing

A 2012 study entitled, Price Discrimination in the Housing Market, found that like the poor paying more for various goods and services, the black middle class pays more for a home:

No matter what the ultimate reason for the price premium, our results imply that systematic, robust racial differences in the price paid to buy a home – on the order of 3 percent on average in multiple major US markets – persist to the present day, long after many of the most overt forms of institutional discrimination have been eliminated. Considering the average purchase price paid by a black homebuyer in our sample is $177,000, this translates to an average premium of about $5,000 per transaction, a substantial amount given the average income of black households in these cities.

The costs of racism on the black middle-class are evident in the difficulty in securing home loans. For African American joining and remaining part of the middle-class is a precarious and difficult task because of racism. According to a report in the New York Times, black homeowners otherwise eligible for traditional fixed rate 30-year mortgages often had subprime loans. In NYC, it "found that black households making more than $68,000 a year were nearly five times as likely to hold high-interest subprime mortgages as whites of similar or even lower incomes. (The disparity was greater for Wells Fargo borrowers, as 2 percent of whites in that income group hold subprime loans and 16.1 percent of blacks)."

Additionally, Joe Weisenthal, with Did Racist Subprime Lending Cause The New York Foreclosure Crisis? notes that according Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shawn Donovan, "Roughly 33 percent of the subprime mortgages given out in New York City in 2007, Mr. Donovan said, went to borrowers with credit scores that should have qualified them for conventional prevailing-rate loans." Differential access to different types of loans has huge financial cost. "These practices took a great toll on customers, Weisenthal notes. "For a homeowner taking out a $165,000 mortgage, a difference of three percentage points in the loan rate -- a typical spread between conventional and subprime loans -- adds more than $100,000 in interest payments." As noted in the article, the prospect of paying an extra 700 dollars a month over 27 years highlights the financial cost and burden resulting from subprime loans.

Housing discrimination in all its forms demonstrates the precluded benefits of middle-class status to many African American families, but the ways in which racism is shrinking the size of the black middle-class. Evident in foreclosures, the resulting lost wealth, and the overall financial burden of racism, a Black middle class is bound to be fundamentally different from a white middle class.

The consequences of these historic and ongoing practices of discrimination are clear. "Segregation of neighborhoods and communities often means, for African Americans, less access to schools with excellent resources, key job networks, quality public services such as hospital care and quality housing," writes Joe Feagin and Kathryn McKinney in The Many Costs of Racism . "The later factors, less access to quality housing, also limits the ability of African American families to build upon substantial housing equity, a major source for the wealth passed along by families for several generations." These are the costs of racism for all African Americans.

According to Carmen R. Lugo-Lugo, professor of Critical Culture, Gender, and Race Studies at Washington State, "The bottom line is [that] there is such a thing as a Black middle class, but not all middle classes are created, valued, or treated equally."

In fact, a whopping 45 percent and 48 percent of black children who grow up as part of a middle-class family (in the 2nd and 3rd lowest incomes, out of 5 categories) will experience downward mobility while the same can be said for only 20 percent and 16 percent of whites who grow up in the same income categories. So spare me the "race" does not matter: just take a look at the numbers. Look at the middle-class as it stands today. Just look at the experiences of the middle class and you can see how racism operates in and through it.

And just to give you a few more things to think about: look at stop and frisk and racial profiling, look at the fact that black women take home 62 cents for every dollar pocketed by white men (Latinas earn 53 cents; black college graduates earn 69 cents), look at the fact that blacks in Wisconsin and Maryland paid on average 800 dollars more for car loans from Nissan. According to NYT, "Among the largest states, the study also showed that on average blacks paid $245 more in Connecticut, $339 more in New Jersey and $405 more in New York. In Texas, the black-white gap was put at $364; in Florida, it was $533."

What should be clear from the above information (and the countless research) is that because of racism, because of a history of racism, because of persistent racism, and because of individual prejudices and systemic racism, it is hard to achieve black middle-class status. It should also be clear that because of racism, because of a history of racism, because of persistent racism, and because of individual prejudices and systemic racism, when it is achieved, it is precarious -- since it is based on income and not assets (wealth); since the mechanism to achieve and maintain this position are threatened daily. For those who take the black middle class as evidence for "no problems," would the prospects of living under these conditions and facing this level of discrimination elicit hope and optimism from you.

Denial: The Biggest game in town

In listening to cable news, in reading comment sections, and in the public discourse at large, a common theme emerges as it relates to issues of race. Dismissing claims of racism by describing them as a "crutch," accusing others of playing the race card, and denying the realities on the ground with claims about whining and hyper-sensitivity the parameters of conversation about racism are constrained by its deniers (for a thorough discussion of the language, frames, and narratives of deflection and denial, please read, Bonilla-Silva 2003). We are told over and over again that the injustices of racial profiling, housing discrimination, prison disparities, segregation, educational inequality, and countless other issues are not about race but something else. That something else often takes the form of "cultural arguments" and others that blame communities of color for inequality and inequity. In other words, the racism deniers push the conversation away from racism, white privilege and systemic failures toward one of pathologies, values, personal failures (all wrapped up in stereotypes) and other ideas that focus on the purported cultural deficiencies of people of color.

This is where celebrities, the black elite, and even the black middle-class come into focus. These racism deniers cite a black middle-class as evidence that race doesn't matter. While denying the discrimination and systemic racism as it constrains the opportunities afforded to working class and poor communities, these arguments rely on a fantasied reality of the black middle-class to substantiate right-wing arguments blaming the poor - and its work ethic, values, culture - all in the name of celebrating American exceptionalism.

"The clock has been turned back on racial progress in American, though scarcely anyone seems to notice, " argues Michelle Alexander in New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in an Era of Colorblindness, adding, "All eyes are fixed on people like Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey, who have defied the odds and risen to power, fame, and fortune" (2010, p. 175). While writing about the "black elite" as sources of evidence Alexander argument works with discussions of the black middle-class. While clearly Obama, Oprah and Michael Jordan are widely deployed as evidence of not only American exceptionalism but the availability of the American dream to every American, it has become increasingly evident that the racial denial crowd is equally comfortable citing the black middle class as their "it's all good" narrative.

"Socioeconomic mobility says nothing whatsoever about the existence of racial oppression," notes Paul Heideman, a lecturer at Rutgers University. "There were slaves who saved up and bought their freedom, and there were plenty of black folks who started businesses and thrived under Jim Crow. This does not constitute evidence that these were racially egalitarian social orders." In the end, you can deny these realities until you are blue in the face, your denial of these realities will not make them go away.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of the just released After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press) as well as several other works. Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, Feminist Wire, and Urban Cusp. He is frequent contributor to Ebony, Slam, and Racialicious as well as a past contributor to Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris.

Published on August 28, 2012 16:42

The Unlocking*: Joining the Conversation Around Lupe’s ‘Bitch Bad’

The Unlocking*: Joining the conversation around Lupe’s ‘Bitch Bad’by Ádìsá Ájámú | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I admire Lupe Fiasco for offering us another contemporary example of what conscious artistry merged with rooted activism looks like. I respect his unwillingness to use black pathology as a scaffold to climb to success. Trafficking in Black pain and sorrow and then using some miniscule portion of the profits for uplift has been used so often by everyone from politicians to drug dealers to preachers to aspiring media moguls and rappers that I wouldn’t be surprised if it was used as case study at Harvard Business school. But if you gotta bleed me to feed me, I’ll pass on the meal. I appreciate that his music asks more of us than to just bob and weave as if high from the last hit of a bangin bass line, that it asks us to join him in a conversation. Which is what I think his song “Bitch Bad” is: an invitation to a conversation.

I love the message in “Bitch Bad” more than the song. And I applaud any brother or sister trying to illuminate the ills that hide in the shadows of white supremacy that reside in regions of our minds especially with so much negativity clouding the airwaves. But here’s my discomfort: With so much work for brothers to do on themselves within this patriarchal order I am still a bit uncomfortable with men instructing sisters on the finer points of womanhood, no matter how well intended.

Is the tradition of brothers challenging other brothers on and off wax around patriarchy so storied and grounded in our ethos that we are now free to instruct women? Because I haven’t seen very many brothers correct each other about what their sons listen to? Nor have I seen very many brothers challenge each other around respecting women with the same alacrity they seem to have received this song. Nor have I seen brothers challenge one another about listening to songs that are clearly misogynistic. I hear an awful lot of brothers talk about the artistry of Hip Hop while equivocating on the misogyny of Hip Hop: “Well, that track about rape and murder, that’s just one track”…”he aint talkin about all women and you know some women really are bitches.” And was it not brothers who elevated the word bitch to damn near a synonym for Black woman, and managed to go platinum doing it? That’s not a critique of Lupe's efforts. I’m simply a participating in the conversation and sharing my discomfort and concern about who is best positioned to give certain messages, and the ways in which patriarchy empowers men to speak forcefully on women’s behavior—to excoriate and correct them—and the ways in which men and women are conditioned to accept that as progressive. Just ask Congressmen Akin and Ryan; just ask folks who want to hold forth on women reproductive liberty.

Patriarchy is premised upon women being told by men who they should be and how they should act: It’s about situating them in the world according to men's whims. Sometimes who brings the message is as important as the message because it conditions how we receive it and examine it for its quality of truth. Don’t believe me: How well do you think Black folks would receive a white rapper doing a song instructing Black folks on the ills of using the N word, especially given that Europeans introduced the word in the first place.

I love Hip Hop and in many ways it is our Rorschach test. It was the first art form in which I grew up and the first art form that grew up in me. I'm of that generation of brothers that grew up celebrating in hip hop even as it gradually morphed into a more materialistically grotesque misogynistic apparition, only to later challenge it without really changing or challenging our participation in the patriarchy that created it. The very patriarchy that created the foundation for our manhood—this ain’t aqua boogie, you cant swim in the water of patriarchy not get wet. Funny thing about foundations is if you destroy them, then everything you built upon them also falls. Which is why a lot of men (and a whole lot of women) have a vested interest in retrofitting patriarchy rather than demolishing it. And because the demolishing of a foundation, no matter how unstable, is too uncertain, our equivocations on patriarchy are what allow us to sleep in house built on faulty foundation standing on a white supremacist fault line. And in this society when it comes to meaningful manhood and womanhood: We are in collusion with our confusion.

Even as we rush to pronounce ourselves progressive anti-patriarchalist (it is no longer cool for progressive brothers to overlook patriarchy under the guise of artistic expression one now has contextualize their complicity for proper cover before pressing play); even as we pat ourselves on the back for finally acknowledging what should have been as obvious as oxygen from the giddy up: that women deserve our respect; even as we celebrate those brothers in hip hop who have addressed misogyny in their records or in their writings as critics (despite the rhetorical distinction patriarchy is misogyny; it’s the velvet gloves over the fists of woman hatred): We often overlook that we, progressive brothers, didn’t so much arrive at this luxurious progressive space so much as we were brought here by sisters like dream hampton, Joan Morgan, Raquel Cepeda, Imani Perry, Tricia Rose and many others, who loved us and the music enough to expect both of us to reach for our higher vibrations. We may pride ourselves on the space we are in now, but we should remember the meter is still running and we have yet to pay the full fare to those sisters who brought us here. So much of how we receive and celebrate Lupe's message with regard to women is more a product of their efforts than that of progressive brothers.

It is one thing to celebrate and applaud a message that is long overdue; it is another to support it by putting our principles in practice in ways that do more than cheers from stands. What good does it do to applaud Lupe's efforts if our spotify/ ipod/pandora playlists could pass for the soundtrack for a Luther Campbell biopic; if our best moments are spent playing cumulonimbus clouds in a strip clubs— if your soul is attached to a pole; if our best idea of womanhood is shrinking them to fit into our most microscopic conceptions of ourselves; if our ideas of loving and partnership begin with the Bible, the Koran or Odu and put always end up in the adult movie section.

I’m not hating on folks choices or what folks legally do to keep their paper game strong. You do you. I am merely pointing at that we live in world of connections, that it’s all connected, that were all connected. We are all a part of the problem and a part of the solution. That everything we do says some things about us, about who we are, about what we value, about how we really feel. Our values are not given to us nor are they inherited (what we get from our parents are their values, not ours). Our values are earned in the Octagon of life, by what we are willing to sacrifice to preserve them, by how far we are willing to go to advance them, what we are willing to do to defend them and how consistently we live them.

Pushing yourself forward, while simultaneously pulling yourself back is an exercise in inanity. You see we, Black folks, want to be free, as long as we dont have to change the things we enjoy that also enslave us. We love sharing our religious faiths, just dont ask us to give up the things that undermine our spiritual growth. We love tolerance, just don’t ask us to give up our hard earned prejudices. We love judging, just don’t judge us. We love equality, just not for the folks whom we feel are unequal. We love our music, so what if it denigrates us, disrespects us, provides permission for others who don’t know us to do the same…That shit was mad disrespectful but yo I was feelin’ that joint…You see that’s the inanity of our insanity: We want to be free as long, as we don’t have leave the plantation.

Hip Hop has always been more than street journalism latticed over sixteen bars, we never needed MCs to tell us what we were living on the daily, no matter the weak-kneed excuse some rappers and their apparatchiks put forward for trafficking in black pain and sorrow for profit. At its higher vibrations hip hop, like jazz and the blues, is quintessential Blackness—celebration, cerebration, confrontation, improvisation, transformation and transcendence—disguised as sound waves reminding us that we “begin in earth and last”, as Neruda would say. True creative genius for a people at the bottom is about converting those sixteen bars into sixteen rungs on a ladder of liberation.

This is the beauty of Lupe’s artistry, here is an artist committed to using his sixteen bars as a GPS helping us locate himself-ourselves, to orient himself-ourselves and invite us to have a discussion about the best route to the reclamation of our best selves. As artist sometimes you have to follow your inspirations and seems to be following his—and I love him for it—but I just think this would have been a more forceful song if it had been directed to the brothers, who so often are producing the music that so many sisters self denigratingly vibe to.

I love Lupe and dig the weight he has decided to carry. Love the message, I’m just not sure brothers are the most effective ones to carry it forward to anyone other than other brothers. Some things are better left to be worked out in circles of women. I love hip-hop because is it for us, by us and about us. I just love Black folks more. And if you ask me to choose between something that sounds good but disrespects us, I’ll choose us every time, and look for my sixteen bars of bliss somewhere else.

*The Unlocking - Ursula Rucker's reminder.

***

Ádìsá Ájámú serves as the Executive Director of the Atunwa Collective Community Development Think Tank located in Los Angeles and is co-author of The Psychology of Blacks: An African Centered Perspective and the recently published fourth edition of The Psychology of Blacks: Centering Our Perspectives in the African Consciousness(2010).

Published on August 28, 2012 12:15

August 27, 2012

Each Generation Must Discover Its Own History: Some Thoughts on the Richard Aoki Debate

* Also appears at 8Asians.com

PART I:

“What did you know and when did you know it?”

That was the question thrown in the face of Old Left supporters as reports belatedly surfaced of atrocities committed by the Soviet Union under Stalin. The allegation was that leftists in America (and beyond) were such naïve and blind ideological proponents of Russian Communism that they idealized the Soviet utopia and turned a blind eye to crimes against humanity. Of course, the right wing and the state wanted to do everything it could to discredit left-wing activism and the ex-socialists turned neocons smugly declared that they were ahead of the curve. But the liberals also were deeply invested in this line of questioning. Though they worked in coalition during the New Deal and World War II, liberals and leftists had a stark falling out during the Cold War, when (to make a long story very short) leftists accused the liberal establishment of selling out the people, kowtowing to the imperialists, and being complicit in the McCarthyist purges. So with supposed exposes of the left, the liberals sought to prove that they were the sound minds who pursued a rational course of democratic reform. A generation of scholars studying the American Communist Party from the 1950s through 1980s was caught up in this debate. Left scholars upheld the CPUSA for its challenge to U.S. Cold War foreign policy and claimed vindication as the liberals dissembled during the Vietnam War. Liberal (and to be fair, left-wing “anti-Stalinists” too) scholars denounced the CPUSA for being a puppet of Moscow that put Soviet directives ahead of its purported mission to serve the proletariat.

The debate was not irrelevant. It challenged activists to think about how they related to international “models” of revolution, how to understand the proper and improper deployment of state power, how to compare and contrast bourgeois and proletarian forms of democracy, and so on. But the debate did not speak to the issues on the minds of young activists coming of age in the 1960s/70s—whose global imaginations were inspired by China and other Third World models of revolution—nor by my generation of activists coming of age in the 1980s as struggles over apartheid, multiculturalism, and US intervention in Latin America took center stage. Robin Kelley’s first book Hammer and Hoeshowed us how to look at the history of the left from a grassroots perspective: the Communist Party could serve as a symbolic image of an alternative to capitalism; it took stands for racial equality that the cautious civil rights groups were more reluctant to take; and it could provide vehicles for those who wanted to engage in mass organizing against Jim Crow and class exploitation. The real debate and action occurred on the ground and regardless of what happened within the USSR and CPUSA, we were part of a legacy of struggle that connected the Old Left of the 1930s and 1940s to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s to the Black Power and Third World Liberation Movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

I start with this story to point out that just as every generation must discover its mission, every generation must discover its history. Today a different question has been posed at Richard Aoki, “What did you tell and when did you tell it?” The Japanese American activist and former Black Panther, Aoki has been named as an FBI informer by author Seth Rosenfeld in his new book Subversives: The FBI's War on Student Radicals, and Reagan's Rise to Power. For a different historical moment, a different connection is being used to discredit and disgrace a different radical activist and the movements he was connected to. But there are some strikingly similar patterns here too—radicalism by people of color is portrayed as something (mis)guided by an external force and left-wing politics are delegitimized while liberalism is offered as a more rational, sound, and democratic approach to social reform.

Aoki is not alive today to answer. When asked by Rosenfeld, he repeatedly denied being an informant and that Rosenfeld was wrong. Once again, the debate is not irrelevant. Rosenfeld’s allegation is an explosive one, and the history of FBI attacks on activists is long and growing. The evidence that Aoki (or any other prominent radical leader) was an FBI informant should be examined by those with expertise on or personal knowledge of the subject. This can’t happen overnight, and I’m waiting to hear a full response from all those folks with much more personal and scholarly connections to Aoki and the Panthers than I have. This includes, among many others, his executor Harvey Dong, biographer Diane Fujino, and scholars of Panther history like Donna Murch.

What I most want to stress is that we need to make sure to place the debate within the broader and proper historical and political contexts it deserves. That’s not something that Rosenfeld has done. On the surface, Rosenfeld might appear sympathetic to the movement because he’s critical of the FBI and one of his primary sources is an ex-FBI agent who has denounced COINTELPRO and supported activist claims against the government. But his research is insufficient, his analysis is frequently flawed, and he has acted in a manipulative and self-serving manner. As I will detail Rosenfeld has violated basic standards of sound historical research and journalist reporting. He also harbors a conspiratorial way of thinking and a political perspective that makes his characterizations of Aoki, the Panthers, and the Third World Liberation Front all suspect. He seeks to defend liberalism while generally discrediting late 1960s radicals of color as violent extremists who set back the gains attained during the earlier era of liberal hegemony. That’s why we need to flip the script. We need to go beyond the narrow question of “what did you tell and when did you tell it” and keep the broader focus of grassroots organizing and movement building at the center of our concerns.

I want to be clear about what I am and am not doing here. I’m not doing a full book review, and my analysis is necessarily provisional. Normally I’d wait for more evidence and interviews to come out, but this is a different case. When an author makes sensational claims in a short excerpt (just like Amy Chua did) that gets wide coverage, we need to respond with what we have to work with right now. So this is largely a review of the controversy sparked by Rosenfeld’s article on Aoki (which he published with a related video and timeline by the Center for Investigative Reporting) accompanied by a quick but incomplete reading of the most relevant parts of the book and footnotes.

1 THE ALLEGATION

Rosenfeld says he interviewed a former FBI agent named Burney Threadgill, who claims to have trained Aoki to be an informant in the late 1950s—around the time he graduated from high school. Aoki is alleged to have given reports on the Communist Party, the Socialist Workers Party, and student activists. Threadgill says he worked with Aoki until 1965 then handed him off to another unnamed agent.Rosenfeld also says that Aoki was still an FBI informant as a member of the Black Panthers in 1967, according to one FBI document that blacks out the name of an informant coded as T-2 but does not censor a parenthetical reference and a note in an adjacent column that links T-2 to Richard Matsui (sic—his middle name was Masato) Aoki. In the book, Rosenfeld says the November 1967 report also states that Aoki (actually it’s T-2 giving the report but Rosenfeld has already concluded T-2 is Aoki) reported to the FBI in May 1967 that he had joined the BPP and was "minister of education.”

Additionally, Rosenfeld says that former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen reviewed his evidence and concluded that Aoki was an informant.

Finally, Rosenfeld cites an interview with Aoki in which he repeatedly denies having been an informant. But he also asserts that Aoki’s added wording that can be taken as “suggestive statements” he was an informer and “an explanation” as to why he was an informer.

There are no documents to backup up the deceased Threadgill, who could have outright mistaken Aoki for another informant he trained—name me an Asian American who hasn’t been mistaken for another Asian by a white person. Nonetheless, if Threadgill’s interview can be found to be credible by corroborating evidence, this is historically significant and should be studied further. We know that in the aftermath of WWII, young Japanese Americans were a bundle of contradictions—still facing intense racism but also being embraced as a model minority. Richard embodied this contradiction—he was a stellar student but also got into fights and trouble with the law. He joined the army in the 1950s ready to be a gung-ho soldier but was discharged and then became a staunch opponent of the Vietnam War. By his own admission, Aoki was politically backwards in the 1950s. Thus, Rosenfeld says that Aoki fit the profile of someone who could have agreed under duress to do informant work in a deal to avoid prison time. This is circumstantial evidence, but at least here—unlike all of this discussion of the late 1960s—it may be consistent with Rosenfeld’s claim.

What we do know conclusively is that Aoki went through a transformation from the 1950s politically naïve youth to a 1960s committed radical. What should we make of this? Rosenfeld attributes all of Aoki’s radical actions in the 1960s to his being an FBI informant. Perhaps further evidence will prove him right, but the burden of proof is on him. Another possibility is that Rosenfeld is dead wrong. Aoki was never an FBI informant, and his political transformation was comparable to what thousands of Japanese Americans and people of color genuinely went through in the 1960s. A third possibility is that Rosenfeld is partially correct: that a checkered past in the 1950s—with the cops, the military, and/or the FBI but not necessarily all of them—made Aoki more angry at the cops, the government, and the capitalist system and fueled his militancy in the 1960s. Or perhaps there’s even another possibility—that if Aoki was forced to maintain a secret relationship with the FBI, he tried to turn it to his or the Panthers’ advantage by spying or reporting on what the FBI was doing. As a sixties activist suggested to me, there were “double agents” who were part of the movement—some with divided loyalties but some with purported full loyalty to the movement that tried to outgame the cops and FBI.

The point is that all we can do is engage in speculation at this point. In reality much of what professional historians do is responsible speculation—emphasis on the word responsible. You should do as much research as possible, only draw conclusions to the extent they are supported by evidence, and consider all alternative possibilities. This is not what Rosenfeld has done. His claim may prove to have some validity, but it may also prove to be false. The point is that he is making much stronger allegations and insinuations than what is supported by evidence and not doing research or contextualization to highlight other plausible conclusions. He has treated those who knew Aoki best as opponents, keeping them at arm’s distance from his research rather than viewing them as vital sources to give him a fuller picture of Aoki and historical context.

We must understand that Rosenfeld thinks like a conspiracy theorist. That doesn’t mean he’s entirely wrong. There was certainly an FBI conspiracy to destroy the Panthers and attack movement activists. And even the most off the wall UFO conspiracy theories probably have some purpose—e.g. the government may not be hiding alien bodies and spaceships but it’s certainly developed secret military weaponry it doesn’t want revealed.Rosenfeld’s problem is he wants to fit all of history neatly into his conspiracy theory.

Rosenfeld’s reliance on former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen is most sketchy. Swearingen is an important witness in general—he has renounced his former work with the FBI and sought to expose COINTELPRO. But Swearingen is also on a quest to uncover conspiracies. He’s aided Geronimo Pratt and the survivors of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, but his greatest notoriety comes from a lifelong quest to prove that Lee Harvey Oswald did not kill John F. Kennedy. (Thanks to Harvey Dong for pointing me to Swearingen’s website www.oswalddidnotkilljfk.com.) Most importantly, unlike Threadgill, Swearingen does not claim a connection to Aoki. It’s fine that he condemns COINTELPRO (and maybe the FBI is also hiding what it knows about the JFK assassination), but Swearingen offers no insight one way or the other in the matter of Aoki—except to offer this ludicrous comment posing as expert testimony:

“Someone like Aoki is perfect to be in a Black Panther Party, because I understand he is Japanese,” he said. “Hey, nobody is going to guess – he’s in the Black Panther Party; nobody is going to guess that he might be an informant.”

While Rosenfeld tried to do so on Democracy Now, there’s no way he can spin this to his advantage. Who in their right mind would think that a Japanese American would be the perfect person to infiltrate the Panthers? You would immediately stick at out and arouse suspicion as to why you were there and where your loyalties really lay. Swearingen, on this specific point, clearly doesn’t know what he’s talking about, has no real knowledge of Aoki, and has apparently never heard of the model minority stereotype which marked Japanese Americans as the antithesis of black radicalism. For Rosenfeld to use this quote as “proof” is spurious, irresponsible, and racist, casting a pall of suspicion over the authenticity of any Japanese Americans (the “perfect” informants) in the radical movement. Again, it leads one to suspect that because he lacks sufficient evidence, he is trying far too hard to make Aoki fit his conspiracy theory.

Furthermore, Rosenfeld has doctored a quote by Aoki to make readers more likely to believe he is confirming his claims. Rosenfeld writes in his initial article, “Asked if this reporter was mistaken that Aoki had been an informant, Aoki said, ‘I think you are,’ but added: ‘People change. It is complex. Layer upon layer.’” The problem is that Aoki never said this—at least not in this manner and in this context. He said, “It is complex” in response to Rosenfeld’s statement the he was “trying to understand the complexities.” As those who knew Aoki best have stated, he often times spoke with humor, irony, and allusion. All he does here is repeat what Rosenfeld said, and he could very well just be stating that history is complex but Rosenfeld’s analysis is based on simplistic logic. Perhaps more significantly, Rosenfeld has spliced disparate statements of Aoki’s together. Aoki never said “People change. It is complex.” in that immediate succession. In fact, Rosenfeld provides no recording or transcript of any kind to indicate the context in which Aoki said “People change.” Again, the question arises: if Rosenfeld was so confident that Aoki’s comments substantiated his claims, why did he feel it was necessary to slice and dice his words and rearrange them to suit his agenda?

We need to review more real evidence. The most damning evidence that Aoki was an informer is Threadgill’s interview, but even that, if true, only substantiates Aoki being an informant until 1965. Rosenfeld focuses on Aoki not where his evidence, if less than definitive, is at least relatively strongest (up to 1965) but instead where it is weakest and flimsiest (1965-69) because that’s what best serves the story he wants to tell. The 1967 FBI document—the only one cited by Rosenfeld—is ambiguous. As Diane Fujino pointed out, “T-2” could refer to an informant assigned to Aoki or a wiretap placed on Aoki. And there’s nothing else for Rosenfeld to stand on. But again, even if Rosenfeld’s interpretation of the 1967 document is provisionally correct, he has no basis for treating it as if it’s conclusive and absolutely no basis for characterizing Aoki as an informant during the 1968-69 ethnic studies strike at UC Berkeley.

Rosenfeld and Swearingen say the FBI is withholding further documentation because it does not want to reveal the extent of Aoki’s work as an informant. To be certain, we do need to press the FBI to release these documents. The FBI is definitely guilty of hiding its secrets and dirty tricks. But Rosenfeld wants us to take a big leap and see that as evidence that Aoki’s work with the Panthers must be part of a bigger FBI conspiracy. How can we be certain what these documents would reveal? It’s just as plausible that the FBI does not want to release more documents because the evidence generally implicates the FBI in nefarious acts against the Panthers rather than offering more specific evidence implicating Aoki. Or again, perhaps the issue is “complex” in ways we and certainly Rosenfeld have yet to consider.

PART II:

2. THE INSINUATION

“Man who armed Black Panthers was FBI informant.” That’s the headline from Rosenfeld’s article on Aoki. http://cironline.org/reports/man-who-armed-black-panthers-was-fbi-informant-records-show-3753

Now Rosenfeld is very careful to say that there’s no clear-cut evidence that Aoki did any of his work for the Panthers at the direction of the FBI and that he’s never found any document saying Aoki told the FBI he gave the Panthers guns. So he’s covered his ass in this regard. But that headline is clearly nudging readers (especially casual and lazy readers) to think that Aoki was actively working to undermine the Panthers when he armed them—and certainly all the initial chatter flying around the web centered on just that thought.

The mainstream media has been shocked by Rosenfeld’s would-be “discovery” that Richard Aoki supplied the Panthers with guns, as if he’s uncovered some previously mysterious figure who forces us to rethink the whole origin and history of the Panthers. But we have openly known for decades that Aoki supplied the Panthers with an initial stash of guns. The Panthers advocated armed self-defense in the age of intense police brutality and a time when most in the black community saw the cops as an occupying army. The Panthers inspired wide support from the community for their militant opposition to white supremacy AND their survival programs. Aoki was a militant and yes, armed, revolutionary activist, but the Panther leaders asked him to give them guns—not the other way around.

We also already knew that the FBI infiltrated and disrupted many civil rights, Black Power, and left wing groups in the era of J. Edgar Hoover. One tactic used was to have agent provocateurs spur radical groups to violence to justify the state using repression against it. The Panthers were heavily infiltrated and got into many violent clashes with the state that devastated their ranks and led to increased internal dissension. While that makes many activists inclined to believe reports exposing yet another informant, we should not let that bias our view of Rosenfeld’s specific claim about Aoki’s relationship to the Panthers.

Now, we need to continue to debate the effectiveness and consequences of the Panther’s initiation of armed self-defense patrols and their decision to confront the state—both done under the auspices of the Constitution—as well as the way they handled incredibly heightened contradictions when the state targeted them. But Rosenfeld has already concluded that arming themselves was a disastrous move for the Panthers and set back the entire movement for social justice. Thus, in his view, Aoki’s supplying the Panthers with guns—something that has, rightly or wrongly, made him a militant folk hero among radicals—makes him immediately suspicious as a potential saboteur. He’s nudging us to connect the dots in order to strengthen his conspiracy theory.

However, the insinuation that Aoki gave Huey Newton and Bobby Seale guns at the direction of the FBI does not make sense—at least not based on the evidence provided at this point. Aoki met Huey and Bobby at Merritt College before the Panthers were founded and helped lead them in study of revolutionary theory. Are we to believe that Aoki helped raise the political consciousness of Newton and Seale, so they would then found a revolutionary party, so he could then arm the party, so that the party could then become a target of COINTELPRO, so that Reagan could benefit by making “silent majority” appeals for law and order AND that Richard Aoki would make sure he kept up the charade by posing as a dedicated and committed activist for the rest of his life? Someone should ask Rosenfeld if he thinks this Manchurian Candidate scenario is plausible—otherwise the misleading aspect of the headline should be corrected and Rosenfeld needs to admit that the circumstantial evidence goes almost entirely against his argument.

What Rosenfeld does conclude is that—regardless of whether Aoki did so at the FBI’s direction—Aoki’s militancy and distribution of arms influenced the Panthers and helped lead to their downfall. He takes Aoki’s role within the Panthers out of context and takes the Panthers advocacy of armed self-defense out the historical context of the late 1960s. Why does he do this? Primarily out of ignorance, but it’s a willful form of ignorance.

As I’ll explain below, most of the book does not concern Aoki or the Panthers—other aspects of the book are discussed and researched to a far greater degree. So Rosenfeld drew media attention to the Aoki narrative not because it’s central to his book but because it was the most sensational sound bite he could use to draw attention to himself ahead of the book release. Of course, this is standard marketing practice for a corporate book publisher trying to maximize profits. But let’s be clear that the mainstream has never heard of Aoki before and doesn’t really care—except perhaps on a local level in the Bay Area—about him as an individual or icon. The story is circulating because of the specific (and largely negative) role the image of the “Black Panthers” plays in mainstream America.

Whenever you hear the “Black Panthers” discussed in the mainstream media, you should be suspicious right away. The Panthers are a fascinating, complex, and contradictory historical entity. But in the mainstream media and mainstream politics, they are almost always a simplified symbol of Black Power—and to most white middle-class people (liberal and conservative) Black Power recalls a terrible time of urban rebellions, when black militants were burning down cities and forcing whites to flee to the suburbs. It’s all part of racist fantasy history: the reality is that whites were fleeing cities for decades, even when whites held urban political power, because capitalists were moving jobs to the suburbs and it was easier to build all-white neighborhoods in newly established suburban tracts. Then, of course, urban rebellions and Black Power militancy only erupted after years of nonviolent resistance and legislative lobbying proved inadequate to overcome white hostility, capitalist maneuvering, and liberal arrogance in the quest for equality.

Whenever certain Americans want to revel in their backwardness and ignorance, they bring to mind the bogeyman of Black Power to remind themselves that they need brutally racist cops, racial segregation, and gated communities to maintain law and order. Whereas movement organizers use history to expose patterns of oppression, these white populists use a warped sense of history to promote this notion of white victimhood. They remind us that America was seriously threatened by “Black Panthers” and that this legacy is still with us.

So whenever a black activist gets into trouble with the cops and the behavior of law enforcement comes under scrutiny—e.g. Mumia Abu-Jamal or Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, (the former H. Rap Brown)—the media will identify them as “Black Panthers,” even if in the case of these individuals (and Angela Davis), the Panthers are only a very small piece of their histories and far overshadowed by other involvements. That’s why CNN’s 2002 story on Rap Brown was headlined “Ex-Black Panther convicted of murder.” Because calling him the “ex-Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organizer”—even if that’s what he’s most historically known for—just wouldn’t have the desired effect. http://edition.cnn.com/2002/LAW/03/09/al.amin.verdict/index.html

And the big thing is that the Panther bogeyman never goes away. The Tea Party is up in arms today about Eric Holder because they say he won’t prosecute bogus charges of voter intimidation of whites committed in 2008 by—you guessed it—the Black Panther Party. Yes, folks, they want us to believe the (new) Panthers swung the 2008 election to make sure we have an evil Muslim as president. Of course, if that’s true then it makes sense for the right wing to pass Voter ID laws to disenfranchise poor people and people of color, right? As Sarah Palin would say, “You betcha!”

Whatever Rosenfeld’s own political sympathies, the marketing strategy he adopted for the book is to present a sensational story linked to the Panthers, when in fact most of his own research and strongest claims are on things not directly connected to the Panthers. Again, that’s par for the course for corporate media and publishing. But it shouldn’t be standard practice for the nonprofit and ostensibly social justice-minded Committee for Investigative Reporting that gave Rosenfeld a platform. And though he doesn’t really claim to be a movement historian, folks should be very clear not to mistake Rosenfeld for one.

Rosenfeld’s Aoki story fuels the idea that the Panthers were not a serious group—that their core identity and program from its origin were shaped by an FBI informant. But the Panthers were deadly serious and deserve serious attention—they were neither a simplistic bogeyman nor idealized revolutionaries. They were part and parcel of a history that must be studied and understood in ways that Rosenfield has no desire to do.

3. THE LIBERAL NARRATIVE

Rosenfeld’s book is generally designed to uncover an FBI conspiracy. In much of the rest of the book (not discussing Aoki), Rosenfeld may have some good points to make about Reagan’s relationship to the FBI and have documentation to back him up. But he’s strongly suggesting that readers make a leap of faith when discussing Aoki’s would-be conspiratorial role within the Panthers and especially the Third World Liberation Front strike for ethnic studies at UC Berkeley.

In fact, most of the discussion about Aoki in the book involves the TWLF at Berkeley—not surprising since the book is mostly about student activism at UCB. Here's the thesis (p. 8): “Each of these men [Ronald Reagan, Berkeley president Clark Kerr, and Mario Savio] had a transforming vision of America and exerted extraordinary and lasting influence on the nation. By tracing the bureau's involvement with these iconic figures, this book reveals a secret history of America in the sixties. It shows how the FBI's dirty tricks at Berkeley helped fuel the student movement, damage the Democratic Party, launch Ronald Reagan's political career, and exacerbate the nation's continuing cultural wars.” Savio—the white free speech activist from the early 1960s—is “brilliant”; Reagan—the right winger—makes a pact with the devil (J. Edgar Hoover) for political ascendancy; Kerr is the reasonable, underappreciated liberal who was trying to be a responsible steward but was a casualty of the new ideological polarization. Three white male protagonists represent the 60s and the transformation of America.

Again, I admit to needing more time to fully analyze the book, but we can at least contextualize it by highlighting how this thesis is entirely consistent with the simplistic white liberal narrative of the 1960s. The general story already laid out by previous books goes like this: the activism in the early 1960s was wholesome, nonviolent, and integrated. But then the late 1960s was dominated by urban rebellions, violent militants, and black separatists who undermined all the achievements of the early 1960s and provoked a white middle-class backlash that led to Nixon, Reagan, and now the Tea Party. The simple story of the 1960s—already ripped to shreds by many, many historians—takes everything out of context, as if the US liberals didn’t push Vietnam and the Cold War, as if most white suburbanites weren’t already against the full program of civil rights and integration, as if there wasn’t a Third World movement for liberation that led US communities of color to see themselves as fighting a war against internal colonialism.

The liberal narrative generally forgets that by the mid-to-late 1960s MLK was so alienated from establishment liberalism that he declared the US government to be world’s greatest purveyor of violence. It distracts us from the failures and contradictions of liberalism. It wants to see white working-class and middle-class voters as manipulated dupes rather than genuine supporters of Nixon’s and Reagan’s racist and imperialist agendas. And especially here, it excludes the context for the rise of late 1960s militancy. Activists from the center-left to the far-left were looking for ways to transform the street force of the rebellions into disciplined, political organization. The Panthers heightened the political contradictions and the physical confrontations with the police and the state to unprecedented levels. Just as Fanon wrote, they tapped into a sense among the people that the violence inherent in white supremacy and imperialism was breeding militant opposition. Aoki provided the Panthers with some of their first guns, but long before that he helped lead Huey and Bobby in theoretical readings that guided their political development when they were Merritt College students. As Diane Fujino has pointed out, this does not fit the profile of an informer. And among many must reads, please see Donna Murch’s wonderful book Living for the City for more on the Merritt College period.

What the white liberal narrative refuses to accept is that young African Americans—sent to die in Vietnam, abused by the occupying force of the police, denied jobs from the shrinking industrial economy, watching nonviolent protestors repeatedly lynched, beaten, and jailed, and portrayed as the enemy by whites guarding their segregated suburbs—did not need any outside force to convince them that America was so rotten at its core that it was time to either burn the whole thing down or organize to overthrow the ruling class. All the liberals could do at this point in history was try to co-opt the insurgent movements in order to preserve their hold on power. Meanwhile the right wing went after the movements with savage ferocity.

If the left’s limitations are viewing rebellion in too celebratory a fashion (as James and Grace Lee Boggs argued, breaking the threads of an illegitimate order is but an initial step toward revolution), focusing too much on state repression as the source of its downfall, and not sufficiently examining its own internal contradictions, the problem with liberal history is its constant focus on the how the far right and far left tore apart America in the late 1960s and its false belief that the mid-20th century era of liberal hegemony was a time of good will and harmony rather than an imposed order that turned a blind eye toward many sources of oppression and repression.

Rosenfeld does provide a twist on the standard narrative. He wants to blame the FBI for being the most influential provocateur that disrupted a unified, peaceful, and democratic movement—rather than a more common liberal target like the Weathermen—but he also wants to delegitimize some radicals of color in the process.

Thus, we need consider Rosenfeld’s portrayal of Aoki in the Third World Liberation Front. His book does not provide any evidence Aoki was working for the FBI during the UC Berkeley ethnic studies strike, so the entire argument is driven by insinuation and based on circumstantial evidence. It goes like this: Mario Savio and the Free Speech Movement were good, wholesome examples of (white) radical (but not Communist or violent) activism in the early 60s. Reagan and Hoover investigated and attacked Savio and the FSM but it was all without merit: every claim that Savio was a Communist or a subversive was dubious because Savio was just a brilliant, articulate proponent of freedom and democracy. (I say “Good for Savio” and will not hate on him.) However, Rosenfeld continues, the TWLF—even though it had some justified claims—was violent and turned off many white students. More than that, for the author’s thesis, the violent and extremist TWLF made Reagan (and Nixon and Hoover) look justified in their repressive calls for law and order. Savio is Rosenfeld’s hero, and he’s using a negative portrayal of Aoki to provide a contrast.

And since the book’s big claim is that it’s exposing a conspiracy, Rosenfeld strongly suggests that the TWLF’s “violent” turn was sparked by Aoki working on behalf of the FBI. His main claims are that: a) Aoki frequently rejected compromise and behind-closed-door negotiating with the administration but instead always pushed for more militant actions, including the use of violence as a tactic to sustain the strike; and b) Aoki, who he admits was a constant advocate for Third World unity, was in the middle of intense conflicts between African American and Chicano leaders of the TWLF. I will let Asian American Political Alliance and TWLF veterans and scholars like Harvey Dong provide the full analysis of these points. But again, let’s make clear that Rosenfeld is not telling us anything we didn’t already know. We know Aoki was not Gandhi, but he was far from alone in this regard. And we know that beneath the public presentation of Third World unity, there were all kinds of suspicions and tensions as activists struggled to hold the TWLF coalition together. None of this circumstantial evidence implicates Aoki as an FBI informer.

What seems clear to me is that Rosenfeld would have portrayed the TWLF as a turn toward violence that prompted a right-wing backlash whether he thought Aoki was an FBI informant or just a revolutionary activist. This is because his general perception of the TWLF is negative—again, in contrast with the good, nonviolent activism earlier in the 1960s. This is clearly a topic he knows little about and does not understand. How, for instance, does Rosenfeld explain why the San Francisco State TWLF erupted into bigger clashes with the police—including a full on police riot—on a more advanced timeframe when Aoki was at Berkeley? He basically ignores this inconvenient truth. SF State is mentioned only in passing. And to show how under-researched and amateurish the ethnic studies segment is, Rosenfeld never even mentions S.I. Hayakawa, the conservative and Reagan-appointed Japanese American president of SF State went to great lengths to smash the first strike in history for a college of ethnic studies. Reminder, this is supposed to be a book on how Ronald Reagan used attacks on radical student activism to advance his political career! I’m sorry but whatever the other merits of his book, I cannot take Rosenfeld seriously when he’s discussing the TWLF. Even more so here, Rosenfeld’s ignorance demonstrates how his portrayal of Aoki is tied to his underlying conviction that there must be an FBI conspiracy to account for the history of the TWLF. (Again, he’s careful to suggest readers make that conclusion without saying it definitively, although he is far more definitive in portraying Aoki as an FBI informant during this period.)

Of course, it’s so much easier to blame Aoki for the “violent” turn in campus protest when you disregard what went down at SF State and don’t even consider the role Hayakawa played in deploying excessive policing and state repression to put down an educational social movement. To repeat, Rosenfeld’s characterization of Aoki is tied to a white liberal narrative of the 1960s that at least in part wants to blame violent activists of color (portrayed here as steered by the FBI) for the demise of liberalism and the rise of the New Right. It fails to place late-1960s militancy in proper context and is in many ways antithetical to the movement history put forward by the founders of ethnic studies.

PART III:

4. THE ICON

I can appreciate how and why Aoki became an Asian American icon. Japanese Americans have used and needed icons in diverse ways. Before World War II, when Japanese immigrants were barred from citizenship or full membership in the American body politic, the community held up Japanese homeland figures as their icons and used economic nationalism as an entrepreneurial survival strategy. The Nisei generation saw all their citizenship rights stripped away, so their leaders put forward Japanese American war heroes as model citizens who proved their ethnic group could make great contributions to America. When this morphed into the model minority stereotype and was manipulated by conservatives and anti-black racists, Sansei radicals looked for models of resistance and Afro-Asian solidarity. Of course, Yuri Kochiyama fit the mold perfectly, but sadly her health issues have limited her in-person exposure in recent times. Richard Aoki was there for those younger activists who needed to be shown it was possible to break the mold and chart a new path forward.

To be frank, I did not know Richard Aoki personally and only met him in passing. I doubt that he was personally well known by most Asian American activists coming of age in the 1980s. When I briefly talked with him later in the 1990s, I was excited to meet him. But I had already begun to question the limits of militant agitation and the form of Marxism-Leninism I presumed he espoused, and I saw Aoki more as a historical figure of interest rather than a potential role model. My view of him changed after seeing the positive impact he had on a younger generation of Asian American activists. He wasn’t telling them to pick up the gun and “off the pigs” nor was he demanding they follow some doctrinaire theory of revolution. He was accepting where they were coming from and encouraging and inspiring them to live a life dedicated to social justice. I have heard from many Asian American and Bay Area activists, who are deeply concerned about the hasty conclusions being drawn about Aoki and troubled that his legacy of Third World solidarity, his warm and generous spirit, and his positive contributions to movement building have been overlooked.

Those who cherished what Aoki gave them should hold onto that. It doesn’t matter what “origin story” people have of Aoki. If you received something genuine from him, no one can take that away from you.

At the same time, we need to generally rethink the issue of iconography—a very personal one for me since I work closely with someone who has become a movement icon. And the more Asian Americans—in and more full and general manner—become part of the narrative of US history, the less we will need to rely on individual icons to represent us. We need to recognize that all people are contradictory because the world is contradictory and to be human (esp. a person of color in the US) is to live a contradiction. The mainstream presents us with whitewashed histories of icons to promote national mythology and patriotism. We don't need it, since we have more important lessons to learn by studying how anticolonial founding fathers like Jefferson and Washington were also racist slaveholders taking over native lands. Nor do we need the capitalist media strategy of building up icons for profit in order to tear them down for more profit. We need to resist the either/or thinking that you are either a pure revolutionary or a total sellout. Too much self-inflicted damage has been done in the name of “purifying” the movement.

We need to embrace contradiction as the source of true change and transformation. We can have imperfect historical role models who learned from their mistakes, as well as some who never resolved their contradictions and thus bequeathed them to us. As James and Grace Lee Boggs have stated, “we are all works in progress”—indeed, revolution is a complex, protracted process not a single moment on a path of linear progress. And let’s never forget that we are the leaders we’ve been looking for.

5. THE FALLOUT

So where do we go from here?

First, let’s demand that Rosenfeld answer the critical questions that many of us have posed and let’s demand that ROSENFELD now release the documents and recordings that he says substantiate his claims. Let’s hear the full, unedited recording of his interview(s) with Aoki. Then let’s do some of our own research and draw our own conclusions about all the evidence viewed in proper context. Let’s NOT set a very bad precedent by destroying a movement activist’s reputation based on the word and agenda of an outsider. If Aoki can be found guilty based on such inconclusive evidence, then none of us is safe. Remember that one of the most outrageous tactics COINTELPRO used to discredit movement activists and spur infighting was to send bogus mailings that purported to “out” FBI informants within the Black Panther Party and other groups.

Second, let’s re-start a longer conversation that people in the movement need to have about how we view state repression, how we respond to infiltration, and how we handle internal contradictions. This is not just a historical matter. When I lived in Los Angeles, I worked closely with Chicano movement veteran Carlos Montes, who has recently been hit with politically motivated charges and has a case pending in court. And there are too many more contemporary examples to count, including spying on peace groups as moderate as the Quakers. One knee jerk response is to “tighten” security and do more internal policing. But too much secrecy can lead us into smaller and smaller circles increasingly divorced from contact with the people. And “internal policing” of the movement is exactly what the cops want us to do when they spread fear among us—it almost never turns out well. We need to develop proactive ways to build a healthy movement culture, resolve non-antagonistic differences, and promote sustainable relationships that preclude us being susceptible to outside agitators or informants.

Third, let’s make this crisis moment a teachable moment. Let’s remember that the truth can and must be convened from every available source. So if Rosenfeld has provided even a partial-truth, we must discern what that is (even if he can’t do it himself) and reckon with it. But let’s not forget that we need to research, write, and study our own movement histories. As Amilcar Cabral said, “Tell no lies; claim no easy victories.” We need to learn from our shortcomings rather than spread heroic falsehoods. We need to analyze our contradictions rather than put our role models up on a pedestal. And most of all, we need a historical narrative of America that shows how all of us who have been labeled and have labeled ourselves as “minorities” are becoming the new majority. Rosenfeld’s book that focuses on three white men to tell the story of how America was transformed during the 1960s will not be very relevant to the America of 2042. The story of the struggle for Third World unity and liberation—a story rife with contradiction and positive and negative lessons—is one that we can claim as central to where we’ve been, who we are now, and who we are becoming. We all need to do a better job of writing this kind of history—including and especially scholars of ethnic studies—for this is a history that will determine our future.

***

Scott Kurashige has been a campus and community activist since the late 1980s, was based in Los Angeles in the 1990s, and has been primarily based in Detroit since 2000. He is the author of The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles and co-author with Grace Lee Boggs of The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century. He is also director of the Asian/Pacific Islander American Studies Program and a professor of American Culture and History at the University of Michigan.

Published on August 27, 2012 15:27

August 26, 2012

The Syllabus: Michael Jackson & The Black Performance Tradition

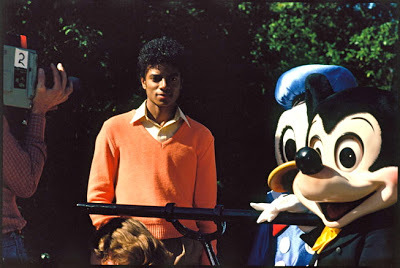

Photo by Todd Gray

Photo by Todd Gray Michael Jackson & The Black Performance TraditionDepartment of African & African American StudiesDuke University AAAS 334-01Fall 2012Tuesday 6:15 pm – 8:45 pmWhite Lecture Hall, 107

Mark Anthony Neal, Ph.D.

Course DescriptionThe central premise ‘Michael Jackson and the Performance of Blackness’ is the question, “Where did Michael Jackson come from?” While there are facts—he was born on August 29, 1958 in a Rust Belt city named Gary, Indiana—what the course aims to answer are the broader questions of Jackson’s cultural, social, political and even philosophical origins. The course will specifically examine the Black Performance context(s) that produced Jackson’s singular creative genius within the realms of music, movement and politics, including the influence of Black vernacular practices like signifying and sampling, the network of Black social spaces known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, the impact of Black migration patterns to urban spaces in the Midwest (like Gary, Chicago and Detroit—all critical to Jackson’s artistic development) and Black performance traditions including Blackface minstrelsy. In addition the course will examine the social constructions of Blackness and gender (Black masculinity) through the prism of Michael Jackson’s performance, highlighting his role as a trickster figure with the context of African-American vernacular practices.

Books

The Last 'Darky': Bert Williams, Black-on-Black Minstrelsy & the African Diaspora | Louis Chude-Sokei

The One: The Life and Music of James Brown | RJ Smith

Moonwalk | Michael Jackson

Man in the Music: The Creative Life and Work of Michael Jackson | Joseph Vogel

On Michael Jackson | Margo Jefferson Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop | Guthrie P. Ramsey*Michael Jackson: The Magic, The Madness, The Whole Story, 1958-2009 | J. Randy Taraborrelli

Week 1— Why Michael Jackson?August 29, 2011

Week 2—“We Wear the Mask”—Black Face Minstrelsy and the Roots of Black CelebritySeptember 5, 2012

Readings:

Chude-Sokei—The Last “Darky” | “Black Minstrel, Black Modernism” (17-45); “Migrations of a Mask” (46-81); “Theorizing Black-on-Black Cross-Culturality” (82-113); “The Global Economy of Minstrelsy” (114-160)

Chin—“Michael Jackson’s Panther Dance: Double Consciousness and the Uncanny Business of Performing While Black” (Journal of Popular Music Studies) PDF

Martin—“The Roots and Routes of Michael Jackson’s Global Identity” (Social Science and Modern Society) PDF

Discussion Question: (Beta)

Week 3—“(What Did I Do to be So) Black and Blue?”—The Rhythms and Melodies of RaceSeptember 12, 2012

Readings:

Ramsey—Race Music | “Daddy’s Second Line: Toward a Cultural Poetics of Race Music” (1-16); “It’s Just the Blues: Race, Entertainment, and the Blues Muse” (44-75); “It Just Stays with Me All of the Time: Collective Memory, Community Theater, and the Ethnographic Truth” (76-95); “We Called Ourselves Modern: Race Music and the Politics and Practice of Afro-Modernism at Midcentury” (96-130); “Goin’ to Chicago: Memories, Histories and a Little Bit of Soul” (131-162)

Roberts—“Michael Jackson’s Kingdom: Music, Race, and the Sound of the Mainstream” (Journal of Popular Music Studies) PDF

Discussion Question (# 1)

Week 5—“All Aboard the Night Train”—Black Masculinity and the Chitlin CircuitSeptember 26, 2012

Readings:

Smith—The One: The Life and Music of James Brown

Clay—“Working Day and Night: Black Masculinity and the King of Pop” (Journal of Popular Music Studies) PDF

Discussion Question (# 2)

Week 6— “Big Boy”—from Gary, to Chicago, to MotownOctober 3, 2012

Readings:

Jackson—Moon Walk | “Just Kids with Dreams” (3-64); “The Promised Land” (65-100); “Dancing Machine” (101-142)

Warwick—“You Can’t Win, Child, but You Can’t Get Out of the Game: Michael Jackson’s Transition from Child Star to Superstar” (Popular Music and Society) PDF

Nyong’o—“Have You Seen His Childhood? Song, Screen, and the Queer Culture of the Child in Michael Jackson’s Music” (Journal of Popular Music Studies) PDF

Discussion Question (# 3)

Week 7—“Ease On Down the Road”—Getting Grown and Taking ControlOctober 10, 2012

Readings:

Jackson—Moon Walk | “Me and Q” (143-176); “The Moonwalk” (177-232); “All You Need is Love” (233-283)

Izod—“Androgyny and Stardom: Cultural Meanings of Michael Jackson” (The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal) PDF

Hollander—“Michael Jackson, the Celebrity Cult and Popular Culture” (Social Science and Modern Society) PDF

Discussion Question (# 4)

Midterm Examination Distributed

Week 8—“Wanna be Startin’ Something”—Birth of the “King of Pop”October 17, 2012

Readings:

Vogel—Man in the Music | “Introduction” (1-29); Off the Wall (30-53); Thriller (54-91)

Danielson—“The Sound of Crossover: Micro-rhythm and Sonic Pleasure in Michael Jackson’s ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’” (Popular Music and Society) PDF

Discussion Question (#5)

Midterm Examination Due

Week 9— “Smooth Criminal”—Breaking Boundaries; Transcending Race?October 24, 2012

Readings:

Vogel—Man in the Music | “Bad” (91-129); “Dangerous” (130-169)

Neal—“Still the ‘Best Intentions'?: Edmund Perry Case Resonates Years Later”

Campbell—“Saying the Unsayable: The Non-verbal Vocalisations of Michael Jackson” (Context) PDF

Discussion Question (# 6)

Week 10—“Remember the Time”—Movement, Memory and MasculinityOctober 31, 2012

Readings:

Khan—“Michael Jackson’s Ressentiment: Billie Jean and Smooth Criminal in Conversation with Fred Astaire (Popular Music and Society) PDF

Brackett—“Black or White? Michael Jackson and the Idea of Crossover” (Popular Music and Society) PDF

Martinec—“Construction of Identity in Michael Jackson’s Jam” (Social Semiotics) PDF

Guest Lecturer:

Thomas Defrantz (Professor of Dance and African & African American Studies)

Discussion Question (# 7)

Week 11—“They Don’t Care About Us”—Michael Jackson and Black PowerNovember 7, 2012

Readings: Vogel—Man in the Music | “History: Past, Present, and Future, Book 1” (170-205); “Blood on the Dancefloor” (206-217)Fischer—“Wannabe Startin’ Somethin’: Michael Jackson’s Critical Race Representation” (Journal of Popular Music Studies) PDFRossiter—“They Don’t Care About Us”: Michael Jackson’s Black Nationalism” (Popular Music and Society) PDFDiscussion Question (# 8)

Week 12—“Unbreakable”—The Man in a Cracked MirrorNovember 14, 2012

Readings: Vogel—Man in the Music | “Invincible” (218-249); “The Final Years” (250-263)Erni—“Queer Figurations in the Media: Critical Reflections on the Michael Jackson Sex Scandal” (Critical Studies in Mass Communication) PDFGomez-Barris & Gray—“Michael Jackson, Television, and Post-Op Disasters” (Television & New Media) PDFWhannel—“News, Celebrity and Vortextuality: A Study of the Media Coverage of the Michael Jackson Verdict” (Cultural Politics) PDFDiscussion Question (# 9)

Week 13—“Ghosts”—On Michael JacksonNovember 28, 2012

Jefferson—On Michael Jackson

Discussion Question (# 10)

Week 14—“Man in the Mirror”—Michael Jackson QueeredDecember 5, 2012

Readings:

James Baldwin—“Here Be Dragons” PDF

Silberman—“Presenting Michael Jackson” (Social Semiotics) PDF

Gates—“Reclaiming the Freak: Michael Jackson and the Spectacle of Identity” (Velvet Light Trap) PDF

Fast—“Michael Jackson’s Queer Musical Belongings” (Popular Music and Society) PDF

Final Examination Distributed

Published on August 26, 2012 19:58

Are We Witnessing American Decline? The Cafe with Amy Goodman, Karen Finney, and Clarence Page

Al Jazeera English The US is the most powerful nation on earth, but its position of global supremacy is being challenged - economically, militarily and politically. And the person many Americans hold responsible for these failings is the president who promised them change. The worldwide economic crisis of 2008 started in the US and the aftershocks are still being felt today. Unemployment is running at more than eight per cent, productivity is down and the national debt is a whopping $137bn. Such turmoil makes it hard to honour electoral promises. The country is deeply divided. The machinery of government has been tied in knots by partisan bickering and the rise of the right-wing, anti-state Tea Party and the street protests of the left-wing Occupy Wall Street movement are a reminder of how polarised the nation has become. Despite this, Barack Obama, the US president, has pushed through healthcare reform and turned around the failing auto industry. He has stopped the war in Iraq and killed Osama bin Laden. But is this enough to win re-election for a second term? And, whoever wins, will the next president have the unenviable task of overseeing the US' decline?

Published on August 26, 2012 13:38

August 25, 2012

'Sparkle' – the Film Tyler Perry Can’t Seem to Make

Sparkle – the Film Tyler Perry Can’t Seem to Make by Khadijah White | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I loved Sparkle, the recent remake of the 1976 Blaxploitation film. I know, you probably don’t believe me – I’m the Black feminist critical scholar who will go on incessantly about how much I loathe Tyler Perry movies and my rant will include the words “anti-feminist,” “patriarchal,” “heteronormative,” “homophobic,” “essentialist,” and “minstrelsy.” I haven’t watched a new Spike Lee film since that tragedy called “He Got Game,” I refused to see Steve Harvey (a misogynist) give screen time to Chris Brown (another misogynist) in Think Like a Man, and I am still steaming about the colorism involved in the decision to have Zoe Saldana play Nina Simone in an upcoming biopic.

But. I. Loved. Sparkle. Even with the light-skinned protagonists that were called beautiful and gifted while their dark-skin sister was sassy, smart, and never pretty. Even with the awkwardness of watching another black woman pretend to hotcomb Jordan Sparks’s weave. Even when the “bad sister” smoking cigarettes in the hallway while her sisters attended Bible Study. Even – and Lord!! – with the questionable acting skills and the sometimes underwhelming script. Even with all that, Sparkle is quite possibly my favorite movie in recent years.

The film starts with Cee-Lo belting out a soulful ballad on stage, surrounded by raucous Black bodies in a dark nightclub sweating, yelling, and whooping to the music. It’s a scene I’ve seen many times before, but the sight of a crowded Black space filled with music, fashion, and sheer exhilaration triggered a wave of nostalgia and longing so strong, it caught me by surprise. Quickly, I was swept away and pulled into a women-centered world of dazzling costumes, breathless success, and the overpowering gaze of an ever-present spotlight.

The story opens with two fair-skinned sisters preparing to go next on stage. Jordan Sparks plays the title character Sparkle, the shy songwriter who pushes her confident and beautiful older sister, Sissy (Carmen Ejogo), to perform her songs. The opening scene, replete with archetypes donning finger waves and a performer ripping her dress to enhance its sexiness at the last second, also carried complexity. There was a just barely-there hardness in the older sister’s sultry performance and a simple brilliance in the ambition that shone on the face of her sister-lyricist. The characters were not quite as neat as they first appeared, their moves not quite so easy to predict. The contrast of the sentimentality of the rowdy juke joint juxtaposed against the intricate bond of these two sisters sets the tone for the rest of film, which tells a surprisingly rich tale of a musical family of singers finding their way in a 1960s Detroit.

The opening juke joint scene isn’t the only one that feels instantly familiar. As the audience travels with these sisters, we run to catch the last bus home and sneak back to our rooms just to find our mother waiting in her house robe and rollers, chiding us to wrap our hair for church the next day. We go on a first date at a cheap food joint with a guy we don’t really like but might be our best hope for escape, we fall deeply into a heady, dangerous love affair, we laugh with our sisters and stand up to our overbearing parent. The scenes are almost always in intimate spaces – bedrooms, living rooms, the church sanctuary, private home balconies, record store listening booths, and dressing rooms. We are inside Detroit, but outside of its exterior spaces, away from the pain and ugliness of police brutality and Detroit’s crushing poverty. This is a film about inequality and marginality, but as reflected in the uneven contrasts of nighttime performances and hitting rock bottom while weeping in a closet in the light of day.

Whitney Houston plays “Emma,” a single mother of three. She is a strict, bible-toting woman who sings solos in the church choir every Sunday and slips into a deep alcoholic slumber every night. Her third daughter, Dee, (played by Tika Sumpter) is an aspiring doctor who has the dark-brown skin of her father, subtly gesturing to her mother’s history of failed relationships. Her eldest daughter Sissy is living back at home after a failed marriage, trying to make ends meet on a meager department store salary. Sissy is the core of the film, not Sparkle. She is a resolute woman who refuses to unpack her bags at her mother’s home because she won’t accept that she has nowhere else to go. Throughout the movie, Sissy is always trapped – in a body that makes men want to possess her, in a society that limits her capacity to provide for herself, by her lack of education and self-esteem, by the demands and expectations of her siblings, and in the suffocating cocoon of her mother’s home. In a way, all of the sisters seem to be trapped, always yearning to be somewhere and someone else.