Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 969

August 9, 2012

Gotta Sing on the Beats They Bring Us: Gender, Class and 21st Century Blues Women's Epistemology

Blues and the Spirit

A presentation by Dr. Zandria F. Robinson, Assistant Professor of Sociology and James and Madeleine McMullan Assistant Professor of Southern Studies, University of Mississippi.

Published on August 09, 2012 20:25

Just Say No to Blackface: Neo-Minstrelsy and the Power to Dehumanize

Just Say No to Blackface: Neo-Minstrelsy and the Power to Dehumanize by David J. Leonard | HuffPost BlackVoices

In recent weeks, social media was set ablaze with news that an assistant district attorney in Brooklyn donned blackface and simulated prison rape in pictures taken while he was a college student. Troubling and offensive on some many levels, these photos are particularly disturbing given that as a DA in Brooklyn—as part of the criminal justice system that puts black and brown youth behind bars in disproportionate numbers—Mr. Justin Marrus has tremendous power in his community. Further undermining confidence in a criminal justice system that has proven itself to be hostile to communities of color, the sight of Mr. Marrus mocking and disparaging leaves me wondering how these past practices shape his present role as a prosecutor.

Jorge Rivas at Colorlines describes the photos of Justin Marrus as follows:

In one picture -- from an album called "Halloween" -- Marrus sports blackface, a wig made of what appears to be dreadlocks and a tie-dyed T-shirt. "What part of Jamaica you from mon? da beach mon," the caption reads. A second photo -- from an album called "Courthouse for 4th of July" -- shows Marrus and another man simulating sex in what looks to be a cell with white bars.

The sight of his finding pleasure in the simulation of prison rape, his posing with his friends with a fake confederate flag tattoo, and his engaging in the time-honored tradition of blackface, should give us all pause for thought.

Ignoring the fact that the pictures remained on Facebook for six years - evidence that Marrus saw little wrong with them - a DA spokesman defended his colleague: "This is something he did about six years ago while he was in college. He apologized. He admits it was childish and inappropriate." Others, such as Sharon Toomer, have rightly criticized Mr. Marrus. Toomer describes Marrus's actions as a sign of his sense of "entitlement and privilege" and she calls upon all of us to take this matter seriously:

Through my lens as a Black and Latino woman, a taxpayer and a human being, I view these images as dehumanizing, degrading, arrogant, racist and problematic for a public institution. My lens is not that of White men or women, or even Black men and women who are so jaded by the work they do as prosecutors, that they fail to see or connect the dots on how ADA Marrus' past thought and actions may influence his current and future decision-making. A 'let's give him a break and see what happens' is too great a risk for my community.

Although some may dismiss the photos and Mr. Marrus' behavior as youthful indiscretion, as something of the past, and as harmless, these photos point to a larger history, one that whites have yet to reconcile within contemporary culture.

The practice of white students donning blackface is not an isolated incident but reflects a larger trend at North America's college's and universities. Although these spectacles usually take place outside the view of the public at large, the minstrel tradition is alive and well at North American universities. Tim Wise, in "Majoring in Minstrelsy: White Students, Blackface and the Failure of Mainstream Multiculturalism," notes that during the 2006-2007 school year there were 15 publicly known instances of racial mockery. He describes this practice:

For some, it means dressing up in blackface. For others, a good time means throwing a "ghetto party," in which they don gold chains, afro wigs, and strut around with 40 ounce bottles of malt liquor, mocking low-income black folks. For still others, hoping to spread around the insults a bit, fun is spelled, "Tacos and Tequila," during which bashes students dress up as maids, landscapers, or pregnant teenagers so as to make fun of Latino/as.

At the core of these spectacles is a sense of power and superiority. These students feel they have the right to mock and degrade black and brown people. Moreover, because the longer history of blackface is neither taught in schools nor discussed intelligently in the mainstream media, these spectacles also reflect widespread ignorance about the social, political, and cultural implications of minstrelsy. In any case, we see white privilege in action. We see the impact of having citizens that "know little about the history of how ghetto communities were created by government and economic elites, to the detriment of those who live there." We see the consequences and manifestations of ignorance in operation; we see what happens when American racial history is erased from textbooks; we see what happens when whites are more likely to come in contact with people of color through pop culture stereotypes than through personal contact. Evident with Marrus, and with the countless incidents on college campuses, this mix of privilege and ignorance is a recipe for continued racism.

Ignorance, however, is no excuse.

The ability to be ignorant, to be unaware of the history and consequences of racial bigotry, to simply do as one pleases, is a quintessential element of privilege. The ability to disparage, to demonize, to ridicule, and to engage in racially hurtful practices from the comfort of one's segregated neighborhoods and racially homogeneous schools reflects both privilege and power. The ability to blame others for being oversensitive, for playing the race card, or for making much ado about nothing are privileges codified structurally and culturally.

There is no acceptable reason to ever don blackface. It's not a joke; it isn't funny. No claims about humor or creative license can ever make it okay. Blackface is part of a history of dehumanization, of denied citizenship, and of efforts to excuse and justify state violence. From lynchings to mass incarceration, whites have utilized blackface (and the resulting dehumanization) as part of its moral and legal justification for violence. It is time to stop with the dismissive arguments those that describe these offensive acts as pranks, ignorance and youthful indiscretions. Blackface is never a neutral form of entertainment, but an incredibly loaded site for the production of damaging stereotypes...the same stereotypes that undergird individual and state violence, American racism, and a centuries worth of injustice.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of the just released After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press) as well as several other works. Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, Feminist Wire, and Urban Cusp. He is frequent contributor to Ebony, Slam, and Racialicious as well as a past contributor to Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris.

Published on August 09, 2012 20:18

Bomani Jones: 5 Reasons Usain Bolt Owns These Olympics

SBNation

With apologies to all the other winners and great stories that have come out of this Olympics, there can only be one star. Phelps vs. Lochte may have helped drive NBC's ratings, but there weren't 2 million ticket requests to watch swimming. All eyes were on Bolt, who became the first man in over 20 years to repeat as 100-meter champion, and the last guy who did it didn't even break the tape both times. From the name to the antics to the jaw-dropping speed, Bolt has owned London.

And do NOT miss the postscript on poor Tyson Gay....

Published on August 09, 2012 18:53

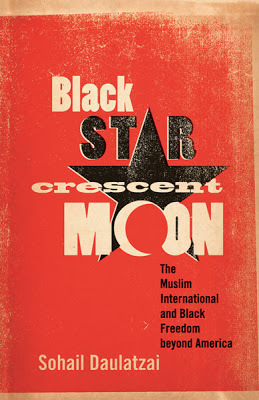

New Book! Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America

BLACK STAR, CRESCENT MOON: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond AmericaBy Sohail Daulatzai

University of Minnesota Press | 288 pages | 2012ISBN 978-0-8166-7586-9 | paperback | $22.50ISBN 978-0-8166-7585-2 | cloth | $67.50

Black Star, Crescent Moon offers a new perspective on the political and cultural history of Black internationalism from the 1950s to the present. Sohail Daulatzai maps the rich, shared history between Black Muslims, Black radicals, and the Muslim Third World, showing how Black artists and activists imagined themselves as part of a global majority, connected to larger communities of resistance.

PRAISE FOR BLACK STAR, CRESCENT MOON:

"Timely and provocative, this globe-trotting book takes you down an almost forgotten road of Black freedom: the one that connects the struggles of the burning ghettos of America to the rage against imperial power in Muslim lands. Shining light on the artists and activists who helped pave that road, Black Star, Crescent Moon vividly shows that Black freedom struggles, whether through art or politics, are always global in scope. Written with an urgency that our times demand, my man Sohail does what we in hip-hop have been doing for decades: uncovering histories, drawing connections, and trying to make people move. Rebel reading for right now!" —Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def)

"Sohail Daulatzai’s Black Star, Crescent Moon is a pathbreaking, genre-shattering work of breathtaking scholarship. It is a work of poetic verve and brilliant analysis that will forever change how we view the international implications and global sites of black freedom struggles." —Michael Eric Dyson

"Black Star, Crescent Moon is a tour de force that has restored my faith in cultural studies. The book is a stunning achievement and Daulatzai reveals an intellectual virtuosity and originality few can match. His formulation of a ‘Muslim International’ alone compels us to rethink Muslim Third World opposition and its relationship to the black freedom struggle." —Robin D. G. Kelley

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sohail Daulatzai is associate professor in the Department of Film and Media Studies and the Program in African American Studies at the University of California, Irvine. He is coeditor of Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas’s Illmatic.

Published on August 09, 2012 11:37

New Book! For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home.

For Colored Boys: The End of an Invisible Life by Clay Cane | HuffPost BlackVoices

"There is no longer dignity in telling the truth" is a line from E. Lynn Harris' debut novel, Invisible Life. Back in 1994 Harris' commentary on the shame of living closeted felt poignant and brutality realistic. At the time being open about your sexual orientation, especially if you were a person of color, did not feel like an option.

I vividly remember the first time I heard about Invisible Life. It was 1995, and I was a teenager who knew nothing regarding the intersection of gayness and blackness. In my uneducated mind, I didn't think black gay people existed. This was a time before Web searches, smartphones, and affirmations from the president. It was easy to feel isolated if you were different; I thought I was the only one.

One day I happened to hear two women talking about Invisible Life on the subway. One of them had the book in her hand as she said, "Child, it's about two faggots!"

I cringed at the anti-gay slur, but my ears perked up. Two men? "I must get that book," I thought.

Later that week, I arrived at a local bookstore to hunt down the mysterious novel. Terrified to enter the "gay and lesbian" section, which was just one shelf, my eyes darted around the store, looking for anyone who might know me. I circled the section a couple of times, ridiculously paranoid, but I finally eyed Invisible Life. On the cover, a man stood in the middle with a man to his left and a woman to his right. I grabbed the book, kept it face down, and paid at the register, making no eye contact. Back at home, I locked myself in my room and read the book in one sitting. Terrified my father would find Invisible Life, I hid it deep in my closet (ironic, isn't it?) and would sometimes dig it out to reread my favorite parts.

Today, Invisible Life is quite dated: A bisexual man lies to his wife about his sexual identity. The storyline has been ridiculously exploited, from homophobic church plays to God-awful, ghostwritten books like On the Down Low by J.L. King. Nonetheless, Invisible Life was a first of its kind. And E. Lynn Harris' journey of love and tragedy was a cautionary tale for me. I vowed that a life of lies and paranoia would never be my reality.

July 23, 2012, marked the third anniversary of E. Lynn Harris' untimely passing. In honor of the impact Harris had on me, I am delighted that today marks my literary debut, in For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home . With Keith Boykin as editor and me as a co-editor and contributing writer (along with three others: La Marr Bruce, Frank Roberts, and Mark Corece), the Magnus-published book proves how far we have traveled since E. Lynn Harris' debut novel almost 20 years ago.

The diverse anthology includes work from 42 different authors. There is Charles Stephens' "The Test," which details the anxiety of living in our allegedly well-educated era of HIV/AIDS. There's also Rodney Terich Leonard's "Teaspoons of December Alabama," which tells an unforgettable story of surviving sexual abuse. Then there's my essay, "Religious Zombies," a comical yet poignant examination of the black church, sexuality, and famous hypocrites like Eddie Long.

The voices in For Colored Boys represent empowerment, which isn't always beautiful and sometimes laced with grit. We colored boys are slapping flesh onto a monolithic image of black LGBT people, who are usually regulated to being accessories for heterosexual women in campy reality shows. With President Barack Obama stating his support for same-sex marriage and Frank Ocean making pop-culture history as the first mainstream R&B/hip-hop artist to come out, For Colored Boys is relevant, regardless of the reader's gender, race, or sexual orientation.

I go back to that line in Invisible Life, which the main character, Raymond, writes in a letter to the woman he deceived for years: "There is no longer dignity in telling the truth." But in 2012 there is dignity in truth. Out of the 42 authors in For Colored Boys, you will not read one story about a tragic homosexual who secretly sleeps with men while his victimized wife twiddles her thumbs. Our diverse stories are unique, powerful, painted with every color, and untold until now. Today, there are rewards for living authentically: freedom, success, and, hopefully, love. For Colored Boys proves we no longer need to live an invisible life.

* * *For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home is available online today, Aug. 8, and in stores on Monday, Aug. 13. Go to 4ColoredBoys.com for more information.

Clay Cane is the Entertainment Editor at BET.com and the radio host of Clay Cane Live on WWRL 1600AM.

Published on August 09, 2012 10:51

“War is God's Way of Teaching Americans Geography”: Propaganda and American Olympic Coverage

“War is God's Way of Teaching Americans Geography ”: Propaganda and American Olympic Coverage by Jamila Aisha Brown | special to NewBlackMan

One of my most vivid memories of childhood was explaining to the St. Louis suburbanites in my sixth grade class that I visited Panamá the country and not Panama City, Florida over summer vacation.

“You know, we have a canal there…we just invaded it…” I said sheepishly to a room full of blank stares and quizzical looks (even though about thirty percent of the children in my school were military brats).

My guess is that because I'm Black and darker skinned it was then natural for them to conclude that Panamá must be located in Africa... but that's another article.

What that moment and countless others before and after taught me is that although the United States of America is a self-proclaimed beacon of freedom throughout the world, Americans have never proclaimed to be the best at really understanding the world outside itself. After all when you’re the best, who cares about the rest, right?

One need only look to the evening news to see lack of reporting on global affairs. Rarely does world news consist of current events abroad, but rather selective stories on international issues that coincidentally directly impact the security, economy, and/or political position of the United States.

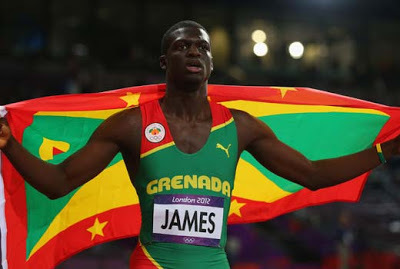

The feature on Grenadian 400 meter track and field phenom Kirani James, which aired Monday night during NBC’s primetime Olympic coverage, reinforced the narrative that this American exceptionalismproves no exception. Many of us race bloggers, activists, and academics have kept a critical eye on the dynamics of race, sports, and gender these Olympics. Cringing when Bob Costas mentioned former dictator Idi Amin as Uganda joined the opening ceremony’s parade of nations, petitioningwhen an advertisement featuring a monkey aired after Gabrielle Douglas’ historical all-around gymnastics victory, and questioning the International Olympic Committee (IOC) who cautioned Australian boxer Damien Hooper against making a geopolitical statement after he wore the Aboriginal flag on his t-shirt in his first match. Yet despite the IOC’s wishes, race and politics cannot be separated from the sporting that brings the diversity of the world and its athletes to center stage.

Monday night’s not so subtle portrayal of how Grenada was “saved” from communism and born into democracy (thanks to President Ronald Reagan), represents a glimpse into the American ideological imagination that began with the Monroe Doctrine and continues on through the War on Terror today.

In a twist of John Quincy Adams’ axiom that effectuated the United States as the watchdog of the Americas, the Reagan Doctrine sought to spread democracy, stamp out communism globally, and defeat Cuban-Soviet influence throughout Latin America and the Caribbean.

“We must stand by our democratic allies. And we must not break faith with those who are risking their live—on every continent, from Afghanistan to Nicaragua—to defy Soviet-supported aggression and secure rights which have been ours from birth,” he declared during the State of the Union Address on February 6, 1985.

Under the Reagan administration the CIA trained Afghan fighters to overthrow Soviet rule, Osama bin Laden among them, and it illegally supplied guns to Nicaragua who used drugs consumed in urban American cities to fund the conflict. Why? For the belief that it was the United States’ “mission” to “nourish and defend freedom and democracy.”

The Reagan Doctrine penned the Grenada incursion as its prologue; it concluded with Panama’s invasion (continued by his predecessor President George H.W. Bush); and identified the Iran-Contra affair as its climax.

Operation Urgent Fury launched its invasion of 7,500 troops on to an island of 91,000 people in the twilight hour of October 25,1983. The headlines did not show the devastation the onslaught brought to the Island of Spice as journalist were held on the island of Barbados, sequestered from reporting the military offensive live.

Outnumbered, outmanned, outgunned, the United States’ forces overpowered the leftist regime, which fell that same day. Nonetheless the armed strike lasted for one week and Grenada remained under U.S. occupation for nearly two months. Leaving the island of nutmeg and mace with a bitter taste.

Having grown up with the dichotomous images of the American media’s coverage of the Panamanian invasion juxtaposed with my family’s personal accounts of the tumultuous era, in NBC’s glossy portrayal of the happy island nation whose salvation was owed to it by the United States I felt a synergy.

The price nations pay for being saved from a tyrant—whether it is a Grenadian coup regime, Manuel Noriega of Panama, or Iraqi Saddam Hussein—often escapes the American media lens. It breezes over the collateral damage of war, invasion, and occupation through erasure of the lives, economies, and infrastructures that lay in ruin after its wake. Spoon-feeding the American public a perennially reinforced self-image of democratic hero.

While the geopolitics of the Olympic games are oft unspoken but unquestionably heard, NBC’s spotlight on Grenada proves how the United States sees its influence abroad.

We haven’t gotten over our savior complex, we haven’t gotten over our penchant for spreading democracy through war, and we haven’t gotten over controlling our media to make you believe that these nations in turn thank us for it.

***

Jamila Aisha Brownis a freelance writer, political commentator, and social entrepreneur. Her entrepreneurship, HUE, provides consulting solutions for development projects throughout the African diaspora. You can follow her on Twitter and engage with HUE, LLC

*Quote from Ambrose Bierce

Published on August 09, 2012 10:30

August 8, 2012

Ill Doctrine: NBC's Awesomely Terrible Olympics

Jay Smooth: What we all can learn from NBC’s achievements in the field of mediocrity.[image error]

Published on August 08, 2012 19:53

Oak Creek Blues

Oak Creek Blues by Courtney Baker | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Writing this hurts. As I have been reading the reports coming out of Wisconsin, following the tweets (@sepiamutiny has been an exceptionally good source), and watching (barely tolerable and woefully meager) television coverage of the mass shooting of a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, my heart has been breaking.

I simply cannot fathom how another mass shooting could break out less than a month after the country was collectively horrified by the killings in Aurora, Colorado. My stomach seized up when it dawned on me that the Oak Creek shooter—and in all likelihood others as well—felt something other than raw disgust and shock about Aurora’s misery. Some one out there must have thought something along the lines of, “That looks like a good idea,” or “I could do better,” or “Ok, so that’s what I need to do,” or—and this is the one that truly chills me, as a black woman—“That guy in Aurora picked the wrong targets.”

That is when it hit me: That despite the denials of the tweeters and the pundits and of the CNN reporter who deliberately cut off the Sikh interviewee who was historicizing violence against Sikh’s in America, Oak Creek is different because of the way that race figures in.

I am not saying, here, that white people are not victims of gun violence. Of course they are, and that’s a reason that, in my opinion, we need to have a serious conversation about gun control in this country. (I hope that it isn’t the case that we can only talk about gun violence when white folks are involved, though.)

Even if the shooter did not turn out to be white supremacist, we should still have been able to read the event through the clarifying lenses of race. Even before Wade Michael Page’s card-carrying membership member of Wage Apathy (a skinhead band, according to Huffington Post) was exposed, we could already recognize patterns that made it most likely that this was a racially-motivated killing spree. He clearly had an intention to kill a group of people, not an individual, and he didn’t show up at a white church service which, presumably, would have been closer to him and easier to infiltrate).

What I am saying is that acknowledging the reality of race helps us to make sense of this tragedy.

Race is not intrinsically evil. When race is celebrated as a feature of one’s individuality and identity, it can be a wonderful thing. But race is a double-edged sword. Just as we use race to understand ourselves, so too do we use race to understand the world around us. In the worst instances, this plays out as racism—when we make assessments of others based on superficial observations that serve no other purpose than to elevate our own identities over that of others.

When I think of the congregants of the Oak Creek gurdwara (“gurdwara” is the name of the Sikh temple of worship) who were hiding for hours upon end, listening to the moans of those who had already been shot, fearing that another shooter or shooters would strike, I have to imagine that they were recruiting all of their analytical skills to help think them out of that dangerous situation. I have to imagine that they were seeing this white guy, with a gun, in their house of worship, and thinking not, “Who among us is he looking for?” and “Why is he so angry?” but, “Oh my god, they are trying to kill us. Again.”

Because it has happened before that Sikhs were killed just for being Sikh. Or, to be more precise, Sikhs were killed because racists only “know” that the Ayrabs responsible for 9/11 are brown and dress “ethnic.” It was that state of affairs that resulted in the death of Balbir Singh Sodi, a gas station owner in Mesa, Arizona who was shot dead on September 15, 2001 by a white man named Frank Silva Roque who was seeking retribution for the 9/11 attacks. Similar retributive murders followed in New York and Texas, and there were numerous threats issued against Sikhs in the days that followed 9/11, and threats are continually renewed.

All of this is bad enough, and convincing enough to me to disqualify all of the race-deniers calls that we shouldn’t discuss what happened in Oak Creek in terms of race and to ignore all of the insults and threats that they hurled against anyone who did. Not only is the recent record of anti-Sikh hatred (I refuse to that condescending term, “sentiment”) pretty damning, there are also major historical precedents in the U.S. that demonstrate exactly how racist violence operates.

The six murdered Sikhs in the Oak Creek gurdwara got me thinking about the four murdered African-American girls who were blown to pieces in their church by a white supremacist’s bomb in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. I fear that the gall, the misdirected fury, and the heretical disregard for human life was on vivid display that September day was on display again in Oak Creek, Wisconsin this August. I weep at the prospect that this country might arrive on September 15th in 2013, at the fifty-year anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing not having learned a damn thing.

From Birmingham. From the Pequot Massacre. From the Holocaust.

We are truly in a worse place today than we were then if we can’t even talk about racism and racialized violence. We simply cannot turn a blind eye to what is going on. And the deniers cannot gaslight me into thinking that what I and my Sikh brothers and sisters have experienced of hatred is not real.

My experiences arereal, and no one can shut me up or shame me about it. Call me an embedded journalist or a field anthropologist: I knowwhat happened because I was there. This is the skin I live in.

I am so unspeakable tired of those I love and of myself being identified as practice targets based on our non-whiteness. I refuse to hear that that statement is racist because if I didn’t inhabit the world watching my back, being mindful of how I might be perceived at any moment by anyone, you would call me a fool. Emmett Till got killed in part for “foolishly” acting like that target wasn’t always pinned to his back.

We can’t live like this anymore. We need to talk about racism in America. If we don’t start talking now, pretty soon nobody will be left.***

Courtney Baker is Assistant Professor of English at Connecticut College. A graduate of Harvard and Duke universities, she researches and writes on African-American visual culture and literature, death, and ethics. Her book, entitled Human Insight: Looking at Images of Black Death and Suffering, is forthcoming.[image error]

Published on August 08, 2012 19:16

e-Patriarchy: Misogyny On-line | The Stream

Al Jazeera English Misogyny online. We'll look at extreme abuse and harassment faced by women on the internet with Alice Marwick of Fordham University[image error]

Published on August 08, 2012 12:14

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.