Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 707

August 14, 2015

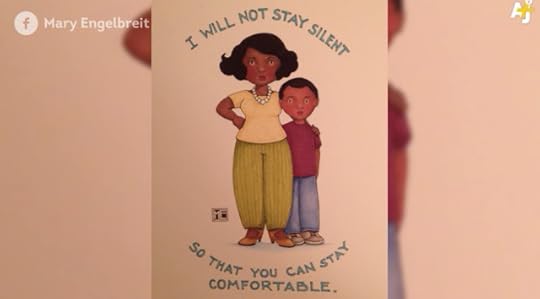

Mary Engelbreit's Anti-Racist Ferguson Illustrations Spark Backlash

'Mary Engelbreit is best known for her heartwarming children's books and illustrations. But her recent work related to police brutality in the U.S. hasn't been well received by some of her fans.'-- +AJ+

'Mary Engelbreit is best known for her heartwarming children's books and illustrations. But her recent work related to police brutality in the U.S. hasn't been well received by some of her fans.'-- +AJ+

Published on August 14, 2015 07:39

Walter Mosley on the Watts Riots

Walter Mosley in from of LA home with his father; courtesy Walter MosleyWalter Mosley, whose "Easy Rawlins" mystery novels are largely set in Watts, looks back 50 years ago to the night when the neighborhood first went up in flames.

Walter Mosley in from of LA home with his father; courtesy Walter MosleyWalter Mosley, whose "Easy Rawlins" mystery novels are largely set in Watts, looks back 50 years ago to the night when the neighborhood first went up in flames.

Published on August 14, 2015 06:10

Do You Want to be Free? by Lawrence Ware

Renee Cox: "River Queen"

Renee Cox: "River Queen"Do You Want to be Free?by Lawrence Ware | @Law_Ware | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

In the introduction to 2014 Forest Hills Drive, J. Cole asks a question that is at once simple and profound. Melodically chanting like a griot at the beginning of a mythical tale, he asks the listener: "Do you want to be free?"

Upon first glance, this seems an uncomplicated question. It is not.

In Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon wrestles with the existential angst that can descend upon an oppressed mind when set free:

Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn't fit in with the core belief.

Once we are aware that our conception of self and community is filtered through the lens of white supremacy, how do we respond? Are we willing to ask difficult questions and pursue new ways of thinking, or do we look for ways to survive in spite of our oppressive conditioning?

Since reconstruction, black people have asked to be seen as human beings—to be treated with dignity. We asked at the turn of the century amid race riots and lynching. We asked in the 1960s with the March on Washington for Jobs and Justice. We asked in the 1980s while policies were enacted that marginalized black economic possibilities and created a criminal justice system that disproportionately imprisoned people of color. We were saying then, like we are declaring now, that #BlackLivesMatter.

Yet a question remains—one that is rarely spoken, but needs an answer. In all this fighting and protesting, amid declarations that our humanity deserves recognition and respect, do we have the ability to live free of white supremacist thinking? Can we see and appreciate black beauty without the oppressive lens of euro-normativity filtering our gaze? Are we able to validate achievement without whiteness as the standard for excellence?

We must be bi-focal. As we demand a white supremacist culture to see our humanity, we must fight the internalized racism that prevents us from seeing our own.

Radical Reexamination of History

We have been taught that we are inferior. We are ignorant of our history, so this was an easy task to accomplish.

History serves as a buffer against notions of inferiority. If a nation is in distress, people will reflect upon the past to remind themselves of their lineage. Pride in self is partly communicated through the telling of history.

There is deafening silence surrounding the state of Africans prior to enslavement. For many, that silence means there is nothing significant to say. Black people in America look back at a historical narrative that marginalizes their contributions. As a result, Black people are cut off from their African intellectual tradition and taught with a philosophy of education that is hostile to black bodies and minds.

Historically, we are taught to see people of color as subplots to the main narrative of white behavior. We center ourselves in whiteness and look back at black activity through an oppressive lens.

We must realize that the way we understand history is important. It is our responsibility to become educated about who we are as African people in the diaspora, but in order to do this properly, there is an additional ideological hurdle that we must clear.

Overcoming shame

Too many black people are ashamed of their blackness. They have internalized white supremacy to such a degree that their goal in life is proving they belong among white bodies. In this vein, their lives revolve around embracing European norms of dress and behavior. They consciously or unconsciously eschew anything that might be African in origin. What they do not realize is this cannot be done.

We are an African people. The percussive nature of our music is African. The way many of us speak from the back of our mouths when comfortable and say ‘brotha’ instead of ‘brother’ or ‘weatha’ instead of ‘weather’ is African. Even taking a racially charged word like ‘nigger’ and replacing the ‘er’ with an ‘a,’ thereby removing the European use of the front of the mouth, is African.

There is so much shame attached to our African ancestry that we do all we can to distance ourselves from it. We are ashamed of our hair. We are ashamed of our body types. We cringe because we are descendants of the slaves that survived. We are ashamed of what should make us proud.

Black people need a revolution of the mind and spirit. Our history was stolen. We were conditioned to see our bodies as unattractive. We devalue black critical intellectualism as being too ‘angry.’ We need to embrace who we are—who we have always been.

Marcus Garvey said: “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds.” He was wrong concerning many things, but he was right about this. We must admit that we are mentally enslaved, and once we admit this, we can do the hard work of freeing our minds.

But the question remains…do you want to be free?

+++

Lawrence Ware is a professor of philosophy and diversity coordinator for Oklahoma State University’s Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to the publication The Democratic Left and contributing editor of the progressive publication RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race for the HuffPost Live, CNN, and NPR.

Published on August 14, 2015 05:03

August 12, 2015

"I Can't Breathe" Jessica Care Moore, Ursula Rucker, Wendel Patrick in Detroit

jessica care moore, Ursula Rucker, and Wendel Patrick performing "I Can't Breathe" at the Sidewalk Festival of Performing Arts in Detroit, MI.

jessica care moore, Ursula Rucker, and Wendel Patrick performing "I Can't Breathe" at the Sidewalk Festival of Performing Arts in Detroit, MI.

Published on August 12, 2015 07:55

If Black Lives Mattered by Rodney D. Coates

If Black Lives Matteredby Rodney D. Coates | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

If Black Lives Matteredby Rodney D. Coates | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Across the country –from Baltimore to Oakland, from Ferguson to Cincinnati, from New York to New Orleans –one can hear the refrain “Black Lives Matter”. Of course, you say, yes we concur. It’s almost trivial to assert the value, dignity, and significance of any lives, not to mention those who are black.

But as we listen to the chants, and the attention being directed at police, as yet another young black male dies –we cannot but wonder why we need to have this conversation. It’s obvious –isn’t it? Maybe not. Maybe we are so caught up in a world of selfies and narcissism that we fail to see past our last post, text, or groupie.

If, however black lives do matter, then it is not because they are black but that they are lives. Our very humanity requires that we recognize this. And in so doing, we should be clear that the issue should not have to wait to be resolved at the end of a police revolver, nor should it have to wait for the press, the protests, or the collective guilt to reach us that we recognize that the problem is neither black, nor is it necessarily one of policing. Rather, it is one that strikes at the very root of our existence –and it has a name –self-worth. We just might conclude that not only black, but red, and brown lives also mattered.

If black, red, and brown lives mattered, then we might just conclude that they should matter enough that we demand that the abysmal dropout rates affecting persons of color in our schools, both locally and nationally, should matter.

If these lives mattered we would hold our schools accountable and in the process hold teachers, parents accountable, and hold communities accountable. We would recognize that absent education and training, these youths are essentially dead on arrival. We would insist that for our kids, our future, that failure is just not an option. That is if indeed they mattered.

If black, red, and brown lives mattered, we would condemn our 30 year war on drugs which systematically singled out blacks, Native Americans and Hispanics, particularly males for differential surveillance, criminalization and incarceration.

If these lives mattered we would reopen the cases, release those thousands that were inappropriately sentenced under our archaic drug laws, paid restitutions, and readmitted within society.

If these lives mattered, we would look at the neonatal and postnatal condition in which black, Hispanic, and Native American infants who are more likely to die prior to term, die during delivery, or not survive past their 2nd birthday. If these lives mattered we might challenge the almost 50% chance of teens and young adults being unemployed or underemployed.

In so doing, we might conclude these problems are systemically linked –that from the cradle to the grave –black, red, and brown lives are dismissed, marginalized, and delegitimized. If they mattered, maybe, just maybe we would systematically –from cradle to grave –dismantle the structures that account for the death and demise of all too many of our fellow humans. That is if indeed we believed that they mattered. And then, maybe we will not have to discover that these lives matter as another young life is cut short. +++

Rodney D. Coates is director of Black World Studies and a Professor in the Department of Global and Intercultural Studies at Miami University. He can be reached at coatesrd@miamioh.edu.

Published on August 12, 2015 07:02

August 11, 2015

"The Babies"--Jasiri X on the Impact of Black Death on the Children

"Produced by Idasa Tariq and directed by Haute Muslim, “The Babies” contains a sample of legendary poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron singing, “but no one stops to think about the babies.” It’s my hope that this video will make us think deeply about the need for us to be involved in our communities, and what steps we have to take as a country, to truly make America a place of freedom and justice for all."-- Jasiri X for Shifting Perceptions: Being Black in America

"Produced by Idasa Tariq and directed by Haute Muslim, “The Babies” contains a sample of legendary poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron singing, “but no one stops to think about the babies.” It’s my hope that this video will make us think deeply about the need for us to be involved in our communities, and what steps we have to take as a country, to truly make America a place of freedom and justice for all."-- Jasiri X for Shifting Perceptions: Being Black in America

Published on August 11, 2015 19:56

#BlackTwitter vs. #HotepTwitter

'Can you advocate social justice for black men, but not so much for black women or black LGBT? A subset within Black Twitter, known derisively to some as "Hotep Twitter," seems to think so. But what is it and why is it problematic for social justice? Treva Lindsey (@divafeminist) + @JamilahLemieux + Sureshi Jayawardene (@ihserus) join host Marc Lamont Hill on HuffPost Live.'

'Can you advocate social justice for black men, but not so much for black women or black LGBT? A subset within Black Twitter, known derisively to some as "Hotep Twitter," seems to think so. But what is it and why is it problematic for social justice? Treva Lindsey (@divafeminist) + @JamilahLemieux + Sureshi Jayawardene (@ihserus) join host Marc Lamont Hill on HuffPost Live.'

Published on August 11, 2015 19:39

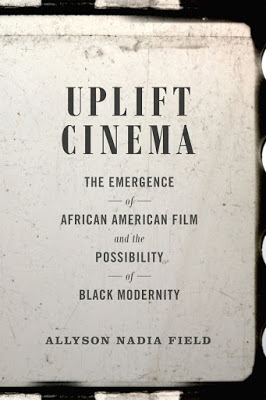

Up From Stereotypes: A Review of ‘Uplift Cinema’

Up From Stereotypes: A Review of ‘Uplift Cinema’by I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Up From Stereotypes: A Review of ‘Uplift Cinema’by I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile) In Allyson Nadia Field’s Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity¸ she situates black visual culture, by way of the cinematic medium in the early decades of the twentieth century, as a tool of racial uplift. Near the end of the preface, Field asserts, “. . . if we are to address the complex genealogy (representational, stylistic, and political) of Black filmmaking in the first part of the twentieth century, we must reconstruct the history of uplift cinema,” which she furthers concedes “has had a deep and lasting significance for the development, dissemination, and public engagement of motion pictures with the advancement of African Americans, a legacy that extends to the broader efforts of Black intellectuals, educators, and entrepreneurs to advance claims to racial, political, and economic progress in the twentieth century and beyond” (xiv-xv).

One of Field’s first sites of inquiry is in the text’s “Preface” when she writes on Oscar Micheaux’s 1925 film Body and Soul insofar as her brief theorization of the film charts the work she addresses in the remainder of the text. The film has a cast that includes Mercedes Gilbert and Julia Theresa Russell, as well as the filmic debut of one Paul Robeson who plays the twin characters of “a charlatan masquerading as a preacher named Reverend Jenkins and his brother Sylvester, an upstanding aspiring inventor” (ix).

The incorporation of the infamous film, Body and Soul, and her “close watching” of it, appears to signal Field’s premise of the book, that being: a discursive wrestling with a manner of double consciousness that falls along the fault lines of respectability politics (as outlined by her reading of William Henry’s negative review of the film and his comparison of it to D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in the newspaper Chicago Defender) and the desire of the auteur, specifically Micheaux’s here, to boycott said respectability politics via Booker T. Washington’s theory of “engraft[ing] false virtues upon ourselves” (as witnessed by Micheaux’s incorporation of an image of Washington as a fixed portrait in many of the film scenes, no different than as a spectral gaze); all of this occurs with a causative end of tracking the possibility of the black modern and emergent African American cinema.

In Chapter One, “The Aesthetics of Uplift”, Field focuses on the visuality and artistry created at both Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes, by way of fund-raising campaigns—“pamphlets, publications, photography, stereopticon displays, pageants, and singing”—, as forms of rhetoric. As the rhetorical forbearers of what could have been considered then “new media”, namely the film, Field proposes that these campaign materials essentially lay the groundwork for what she calls “uplift cinema”.

Chapter Two, entitled “‘To Show the Industrial Progress of the Negro Along Industrial Lines’”, lays out the precarity that often emerges when the control with which one chooses to present the self vastly differs from the lack of control one has in the consumption of that presentation by spectators. Utilizing two films commissioned by the Tuskegee Institute in 1909 and 1913, she argues the agency of the institution as a means by which to create an uplifting narrative of itself, even if that premise conflicted with how a larger audience viewed the institution.

The third chapter, “‘Pictorial Sermons’”, looks at the Hampton Institute’s film production campaigns between 1913 and 1915. As depictions of life at the Institute, these films allow Field entrée to juxtapose Hampton and Tuskegee’s cinematic projects of uplift as historical artifacts of “sponsored and industrial filmmaking” such that they serve “as a complexly functioning component of uplift education that appealed, successfully and unsuccessfully, to a variety of audiences” (29). “‘A Vicious and Hurtful Play’”, the text’s fourth chapter, problematizes how uplift cinema became complicit in the perpetuation of damaging images along racial lines.

By honing in on the incorporation of the Hampton Institute’s film The New Era as the epilogue for some screenings of The Birth of a Nation in 1915, Field addresses the naïveté of including positivity imagery in a project that was/is deeply negative, and how that fosters a larger dialogue around the reception of Griffith’s film in the African American community and the implications for the black modern.

“To ‘Encourage and Uplift’” takes up entrepreneurship and black filmmaking as modes of capturing and disseminating the black modern. In this final chapter, Field, working primarily with filmmakers in the North and what they produced, suggests a politics around communal advancement that was contingent on black creativity existing in front of and behind the camera. Likewise, Field includes an epilogue that returns to Micheaux’s Body and Soul to further contend with the possibilities of the black modern through the medium of cinema.

As seen by the chapter chronology, it appears Field, utilizing The Birth of a Nation as a cinematic fulcrum, surveys, backward and forward, a multiplicity of materialities which give rise to modern black subjects and objects. Moreover, her approach suggests that cinema was and is a frame for not only racial uplift, but also self-determination.

+++

I. Augustus Durham is a third-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Published on August 11, 2015 07:10

August 9, 2015

When Pop Stars Sing Negro Work Songs: Before David Guetta's "Hey Mama," Black Inmates Sang "Rosie"

David Guetta's single "Hey Mama" (feat Nicki Minaj) is built around a sample of "Rosie"--a recording of Black Inmates at the Mississippi State Penitentiary aka Parchman Farm, produced by John and Alan Lomax in 1947. The use of the inmates voices highlights the myriad ways that their labor--primarily picking cotton--was exploited.

David Guetta's single "Hey Mama" (feat Nicki Minaj) is built around a sample of "Rosie"--a recording of Black Inmates at the Mississippi State Penitentiary aka Parchman Farm, produced by John and Alan Lomax in 1947. The use of the inmates voices highlights the myriad ways that their labor--primarily picking cotton--was exploited.

Published on August 09, 2015 21:09

The Watts Riots: 50 Years After the Flames Earl Ofari Hutchinson Remembers

'Earl Ofari Hutchinson chronicles the Watts Rebellion on its 50th anniversary. Hutchinson visits the street corner in South L.A, where he stood as a teenager and watched all the events unfold firsthand on August 11, 1965 and details the conditions of Black America back then and compares them to current conditions of Blacks in Los Angeles and America as a whole today and how much has changed or not changed since then.'

'Earl Ofari Hutchinson chronicles the Watts Rebellion on its 50th anniversary. Hutchinson visits the street corner in South L.A, where he stood as a teenager and watched all the events unfold firsthand on August 11, 1965 and details the conditions of Black America back then and compares them to current conditions of Blacks in Los Angeles and America as a whole today and how much has changed or not changed since then.'

Published on August 09, 2015 20:29

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.