Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 704

August 22, 2015

“Do [N*ggas] Dream of Electric Sheep?” by Mark Anthony Neal

“Do [N*ggas] Dream of Electric Sheep?”by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“Do [N*ggas] Dream of Electric Sheep?”by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)I begin by recalling Philip K. Dick and Rutger Hauer, to make collateral points about the dystopic, post-apocalyptic world that was Los Angeles, well before the Boyz were ever in the hood or had ambitious designs to leave. If Dick’s 1968 novel and Ridley Scott’s 1982 cinematic rendering were glimpses into our now, it was already a then for the generations of Black and Brown that came up both pre-and-post Watts.

As Mike Davis writes in his seminal tome City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, “Hollywood’s pop apocalypse and pulp science fiction have been more realistic, and politically perceptive, in representing the programmed hardening of the urban surface...Images of carceral cities, high tech police squads, urban bantustans, Vietnam-like street wars, and so on, only extrapolate from already existing trends.” (223)

To this Robin DG Kelley adds, in his equally seminal tome Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class, “The criminalization, surveillance, incarceration and immiseration of black youth in the postindustrial city...constitute the primary experiences from which their identities are constructed.” (208)

LA Police Chief William Parker had long faced charges of police brutality directed at Black Los Angelenos before Watts exploded in 1965--it was one of the reasons why Watts exploded; the paramilitary forces imagined by Chief Parker, even then, were later realized by his former chauffeur Chief Daryl Gates.

Parker’s protege, who ran the department from the late 1970s until 1992, was only in charge a few months when his officers shot 39-year-old Eula Love 12-times for an over-due gas bill; 12 years before we knew the name Rodney King. It was then Watts AssemblyWoman Maxine Waters who led a group asking the Justice Department to examine the LAPD’s shooting of more than 300 “minorities” in the previous decade--two generations before Ferguson exploded.

King’s beating occurred six years after Toddy Tee recorded “Batterram.” There were no handheld shareable videos of the small tanks that Gates used to terrorize Black and Brown communities 40 years before cities like Ferguson were using military surplus to dampen the insurrections in their streets.

Straight Outta Compton’s most arresting moment comes at the beginning of the movie--as we are introduced to the Batteram in the context of Eric Wright’s hustling. That moment is quickly followed by Andre Young’s exile from his mother’s home and O’Shea Jackson’s experience with random violence--gangbangers invading a school bus to present a “Scared Straight!” public service announcement and police officers engaging in the standard issue “beat a nigger’s ass” policing that the LAPD excelled at in the 1980s.

The movie’s three “heroes” represent the primary story arcs of the film: the exploitation inherent in illicit economies (both the crack and recording industries); the imposition of the State on Black freedoms; and the role of music as both refuge and response to the State--and its proxies, like record company execs, who in Jerry Heller, Shug Knight and Priority Record’s Bryan Turner, have as much ire directed at them as law enforcement, and unfortunately, women.

The film’s responses to women, law enforcement and record company executives speaks volumes of how this particular quintet of young Black men may have processed notions of Black male freedom. Ironically both the police and record executives, particularly Heller, are allowed to speak back to charges of malfeasance. The women in the film, and obviously those missing from the film, notably Dee Barnes and Michel'le Toussaint, are not allowed to speak back. This is one of the film’s major critical fault-lines, and legitimately so.

Lawrence Ware is right; “the film is misogynistic” in what it says, but more so in what it doesn’t say; but here’s the thing: what the film doesn’t say is what is the always already known, and in a capitalist and hyper-patriarchal culture, in which the male director and producers have some investment, they felt no more compelled to acknowledge that always already known than Mr. Young and Mr. Jackson were compelled--or for that matter aware--to do so twenty-years ago.

It is telling that in the more mature iterations of Mr. Young, Mr. Wright and Mr. Jackson’s lives in Straight Outta Compton, their women partners are all portrayed as active participants in their personal and business affairs. This is less a progressive move than an continued articulation of the utility of Black women in the freedoms of Black men. While as teens, women meant little more than ground-zero for their pursuit of orgasmic desire, as adults Black women served other desires.

As Mr. Jackson told bell hooks more than 20 years ago in an illuminating interview that appears in the latter’s Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, “I think a black woman is the best thing to have, because black women are focused...black women have been the glue. Black women is trying to hold it together.” Mr. Jackson’s tone might be read as progressive in an era when a screed like Shahrazad Ali’s The Blackman's Guide to Understanding the Blackwoman, which advocated the hitting of Black women, was a popular bestseller among Black readers.

Straight Outta Compton’s failings with regards to being honest about the violence that occurred at the hands of one of its “heroes” is disappointing, disturbing, but not unexpected; films that generate more than $60 million on in the first weekend, generally do not fall of the right side of right when it comes to issues of violence against women. If that was the case we’d see more films that openly addressed these issues; That we don’t says as much about American taste and more broadly, what still exist as acceptable representations of women in media, as it represents the choices of a trio of Black executive producers (including Mr. Wright’s widow Tamika Woods-Wright) and a Black director, who produced the most successful weekend opening by a Black director.

Mr. Young’s real-life violence against women is not isolated to him; violence against women remains under-reported and under-prosecuted across the board. Neither does Mr. Young’s violence make him an outlier among those we might index as Black Male genius.

Challenging the gender violence that the late Miles Davis expressed in his autobiography Miles (with Quincy Troupe), Pearl Cleage, writes in Mad at Miles, “he’s the one who admitted to it. Almost bragged about it. He’s the one who confessed in print and then proudly signed his name.” (15). Cleage then adds, “Nobody was ever able to show me where David Ruffin admitted to hitting Tammi Terrell...And nobody was able to provide me with a quote from Bill Withers describing how he beat up Denise Nicholas.” (15)

An image from the opening segment, where a teenaged Young sits on the floor listening to Roy Ayers’ “Everybody Loves the Sunshine”--a moment that both highlights his relationship with the archive of Black music and the level of technical detail he would want associated with the headphones the would bear his name twenty years in the future--is instructive. The soundscape that Young curates also serves as refuge from the demands and expectations of his mother; indeed when his mother encroaches that space, Young literally flees.

Yet another read of Miles Davis is useful here, as Hazel Carby provides in Race Men: “He seeks freedom from a confinement associated with women, and freedom to escape to a world defined by the creativity of men.” Carby continues, “The various women described in Miles are carefully given their place in his material world: they may service his bodily sexual and physical needs, but are albatrosses around his neck when he wants to fly with other men in the realm of ‘genius’ and performance.” (144) Carby’s “Miles Davis” could just as easily be remixed as Carby’s “Andre Young,” as Gray’s opening critique anti-Black State violence might be mashed with Scott’s Blade Runner.

Like the photo-journalists of the early 20th century, social media and hand-held technologies have created a moment of “gotcha” journalism and criticism. This moment is important because it has allowed many progressives to leverage the power of the technology to hold various institutions and entities accountable.

Yet this moment has also created a culture one-notes--where nuanced thoughtful criticism of cultural and artistic production, is often reduced to singular themes. Despite of the necessary critiques of violence against women that the film has inspired, Straight Outta Compton is more than one beat--or beat-down(s) as it were.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, where he directs the Center for Arts, Digital Culture and Entrepreneurship (CADCE). He is the author of several books including New Black Man and Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities.

Published on August 22, 2015 15:40

Meet the Undocumented Immigrant Who Works in a Trump Hotel

'This is a profile of Ricardo Aca, a young undocumented immigrant who works in a Trump Hotel and who has decided to speak out against Trump's comments about Mexican immigrants.' -- +NewLeftMedia

'This is a profile of Ricardo Aca, a young undocumented immigrant who works in a Trump Hotel and who has decided to speak out against Trump's comments about Mexican immigrants.' -- +NewLeftMedia

Published on August 22, 2015 14:40

I Won’t Say Amen: Three Black Christian Clichés That Must Go

I Won’t Say Amen: Three Black Christian Clichés That Must Goby Marcus T. McCullough + Lawrence Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I Won’t Say Amen: Three Black Christian Clichés That Must Goby Marcus T. McCullough + Lawrence Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)In a Black Christian worship experience, you are both expected and encouraged to engage in dialogue. To generate a desired response, the speaker will at times use certain catch phrases to fan the flames of worship. So popular are some of these dialogical exchanges that a Mad Libs-like paragraph was circulated by email giving many Black Church-goers laughs because a number of them could easily fill in the blanks with sayings they’ve heard since their youth.

One such phrase is “Let the church say amen.” Often said by a minister with leadership authority, the anticipated response from the congregation is “amen”—meant to demonstrate understanding and/or agreement. Often, this phrase may follow an important announcement, gentle chiding, or even a joke.

This saying and its expected response are so familiar that even if a churchgoer hears something with which they strongly agree outside of the context of a church, they may unconsciously give the response. The phrase and response is, in this sense, a marker of cultural unity and identity. One often doesn’t even consider to what they are assenting. The response pours out unconsciously and swiftly.

Unfortunately, over-familiarity with this dialogic expectation can be theologically dangerous. The elicitation of “amen” can lead congregants into agreeing with statements and ideas that are problematic. People are often unaware of the problematic nature of these popular phrases, and ultimately assent is granted with no conscious or moral consideration of what is actually being said. This is both disturbing and ironic, particularly since Jesus states in Luke 10: 27 that people should love God with their heart, soul and mind (NRSV). That is, we are to be thoughtful about our worship.

Some of the Black Church faithful, however, are concerned about the propensity to say amen to statements undeserving of such assent and choose to be more critical in the context of worship. We authors are two such persons, and that is why we have written this piece.

It is our intention to examine a few of these popular phrases and articulate why they are dangerous. We do so with the aim of fostering a more critical and authentic Christianity amongst those who belong to Black churches. There are many sayings in the Black-American Christian tradition that need to be reconsidered before an “amen” is given, and the following three must go.

“When the praises go up, blessings come down.”This phrase is often used to elicit an exuberant response from people in a congregation. If a minister finds him or herself unable to get a hallelujah from a room full of sleepy congregants, he or she might utter this phrase to bribe them into participation. The only problem is that it is dangerous theologically and socially.

This phrase turns the Divine into an ATM machine. It paints God as a being hungry for empty compliments and willing to pay for adoration. That’s not how God works. Psalm 19: 1 reports, “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament shows His handiwork” (NRSV). We should see praise as an honor, not as a down payment on a new house.

Further, this phrase has dangerous socioeconomic implications. Does this mean that those who are impoverished are in that condition because they have not sufficiently praised God? Does it mean that the wealthy are all living righteously? Of course not. This cliché has to go.

“Favor ain’t fair.”

This is the kind of statement one may make after getting a job for which many have applied. It’s a statement that communicates the inability to influence divine grace. Yet, it also declares that while one cannot persuade the divine to extend grace, the speaker just happens to be the recipient of an incredible amount. Put bluntly: it’s a humble brag.

It’s similar to how one may get on social media and say, “Let me brag on God,” and then just brag on themselves. Usually the statements end with an obligatory “Ain’t God good?” or “You can’t tell me God isn’t real.” These statements aren’t fooling anyone. They imply that God isn’t good unless you have a large bank account or that one would have legitimate cause to doubt the existence of God were it not for the new car in the driveway.

The phrase “favor ain’t fair” is reminiscent of the song I’m Walking in Authority. When Donnie McClurkin says, “I’m walking in prosperity, living life the way it’s meant to be,” I wonder if he realizes this statement would not apply to Jesus. The same is true of “favor ain’t fair.” There are no set of circumstances that would lead the first century Jew we know as Jesus to look around and say anything resembling a humble brag. If he wouldn’t do it, then neither should we.

“The Bible says…”

The Bible rightfully holds a significant position in the life of the Black Church. Historically, Black-American Christians have cherished the scriptures for their messages of divine liberation, justice, and instruction on how to treat one another. Many Black Christians hold that the Bible is the Word of God, given to human beings from Heaven to guide lives and provide the message about salvation. As such, quotes from scripture carry a weight rivaled by no other source, literary or beyond. To say “the Bible says,” then, is to address something important by appealing to God-given words.

Danger lurks, however, behind the use of these three words. Oftentimes, no citation is coupled with the phrase, thus denying a hearer the opportunity to not only read the scripture for his or herself, but also to read the scripture in its broader context. Further, the phrase “the Bible says” robs the scriptures of their multivocal beauty by treating the Good Book as univocal, despite the fact that the name “bible” is derived from the Greek pairing ta biblia, meaning “the books.” If you are unwilling to do the work required to cite the text holistically, then leave the biblical pontificating alone.

This is not an exhaustive list. There is more to come. But the next time you say ‘Amen,’ make sure it is something to which you agree.

+++

Marcus T. McCullough holds degrees in religion, divinity, and sacred theology from Morehouse College, Harvard Divinity School, and Boston University School of Theology, respectively. He is an ordained AME minister and hospital chaplain. His hometown is Seattle, WA.

Lawrence Ware is a professor of philosophy and diversity coordinator for Oklahoma State University’s Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to the publication The Democratic Left and contributing editor of the progressive publication RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race for the HuffPost Live, CNN, and NPR.

Published on August 22, 2015 06:26

The Risks of Turning Races Into Genes by Matthew W. Hughey

Shea WalshThe Risks of Turning Races Into Genesby Matthew W. Hughey | @ProfHughey | HuffPost BlackVoices

Shea WalshThe Risks of Turning Races Into Genesby Matthew W. Hughey | @ProfHughey | HuffPost BlackVoicesFrom 22-25 August, sociologists from around the nation and world will descend upon the Windy City of Chicago to discuss sundry issues as they participate in the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association. One issue, however, is quite controversial: do genes or the social environment determine our behavior and health? Precisely, does nature or nurture determine the outcome of racial differences and racial inequality found throughout society?

Many readily acknowledge scientific advances are a necessary part of an improving society. From making cars more efficient on the road and beaming pictures from Pluto across the solar system to Earth, to developing new medical procedures to help us live better and making a longer lasting light bulb. Despite the many improvements science affords, cultural bias and normative assumptions can undergird the scientific methods and lead us down a dangerous path that has plagued American society for centuries. This path relies on a logic about race and difference that was and continues to be shared by many: from Thomas Jefferson to Dylan Roof, the white supremacist who murdered nine African American churchgoers in Charleston this summer. What may be even more surprising is that a variation of this same logic can infiltrate science and influences how we understand who achieves better jobs and even who succeeds at professional sports.

In the just released issue of The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science we edited, I have gathered (with Professor W. Carson Byrd) an array of experts on race, science, technology, and society to explain how the fiction of "race" can have very real consequences. By exploring both biological determinism and racial essentialism together--what I and Professor Byrd call the "ideological double helix"--we explain how misunderstandings of race, genes, and inequality frequently creep into supposedly an objective science.

First, some explanation of our terms: "Biological determinism" is the belief that race is a genetic reality that regulates how we behave. Correspondingly, "racial essentialism" is the belief that people of different racial and ethnic groups have specific behaviors that are unique to their group. When these two beliefs intertwine--similar to the double helix of DNA--they provide a powerful faith that distorts reality, even among our best and brightest. Many then interpret racial inequality as a "natural" set of differences and outcomes, and can be dismissive of how the unequal lives we lead are powerfully shaped by the social environment.

The recent expansion of genetic and genomic research offers many advances in understanding possible human differences and lived experiences. With a swab of your cheek, you can find out your ancestry; possibly filling-in blanks about your family's origins and connections with other people. With a few tests in a lab, you can have a set of medicines tailored to your personal needs and purportedly tied to your racial identity. Through an analysis of a DNA sample left at a crime scene, scientists and law enforcement can create an artist rendering of the suspect down to their supposed racial group.

You can even file a lawsuit because your baby does not have the same skin color, facial features or hair as you would expect someone of a particular race to have at birth after using artificial insemination, as was literally the case made in Cramblett v. Midwest Sperm Bank, LLC (2014). At the heart of this lawsuit is the belief that people of different races have meaningful genetic differences that result in different outcomes, which is similar to the beliefs shared by Thomas Jefferson in his Notes On the State of Virginia (1787), mass-murder Dylan Roof's online manifesto, and among everyday people on the street discussing why some children learn more readily than others, why some people vote particular ways in elections, and why professional athletes are seemingly more likely members of one racial group compared to another.

What the contributors to our volume discuss is how science and society continue to produce the myth that races are real human differences that are too-often immutable and lead to natural inequalities. After the human genome was mapped after a decade-long international project in 2000, leading scientists and former President Bill Clinton announced that race at a biological level did not exist. This did not stop the belief, among scientists and non-scientists alike, in genetically-derived racial differences. In fact, a major pursuit of contemporary science is to investigate how race exists in the minute differences that distinguish people from one another.

While it is true that geneticists have mapped clusters of genetic material within the global population, these groupings are not so much "natural," objective subpopulations that we could call "races," but are rather collectives that analysts construct using computer programs. That is, when looking for race at the genetic or genomic level, we can come away with research findings that are consistent with any "racial" classification scheme one wishes to find. If we believe there are five racial groups, we can then find five clusters of genetic material to match up with those five racial groups. However, if we believe there to be fifty racial groups, we can also then discover fifty clusters of genetic patterns that seemingly validate the fifty-race assumption.

"Race" is man-made, and much of the scientific enterprise has traditionally supported the myth that racial differences accurately represent real, biological differences among humans. These beliefs limit how scientists, policymakers, and everyday citizens can work together to tackle the real racial inequality of today. By increasing the dialogue of how we can tackle racial inequality regardless of whether we work in a laboratory or not, we can continue to deconstruct the myth that race is found in our genes, and begin to search in earnest for the legal, policy, economic, political, and social forces that make the effects of race all too real.

+++

Dr. Matthew W. Hughey is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Connecticut. He is the author of White Bound: Nationalists, Antiracists, and the Shared Meanings of Race (Stanford U.P., 2012) and is co-editor (all with Dr. Gregory Parks) of The Obamas and a (Post) Racial America? (2011), Black Greek-Letter Organizations, 2.0 (2011), and 12 Angry Men: True Stories of Being a Black Man in America Today (2010).

Published on August 22, 2015 06:14

August 21, 2015

Town Hall Meeting @ The Schomburg: American Policing--The War On Black Bodies

Town Hall Meeting @ The Schomburg on the aggressive policing of Black bodies in America. Contributing to the discussion are Khalil G. Muhammad (Director of the Schomburg Center); Jelani Cobb; Claudia De La Cruz; Darnell L. Moore; and moderator Joel Diaz.

Town Hall Meeting @ The Schomburg on the aggressive policing of Black bodies in America. Contributing to the discussion are Khalil G. Muhammad (Director of the Schomburg Center); Jelani Cobb; Claudia De La Cruz; Darnell L. Moore; and moderator Joel Diaz.

Published on August 21, 2015 21:15

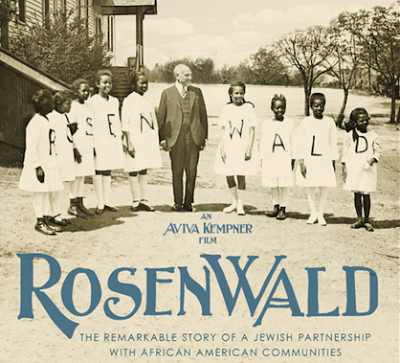

'Rosenwald' Celebrates the 'Black' Philanthropy of Julius Rosenwald

'+NPR's Robert Siegel interviews Aviva Kempner about her latest documentary on Julius Rosenwald, the successful businessman who was also benefactor for African American education in the South.'

'+NPR's Robert Siegel interviews Aviva Kempner about her latest documentary on Julius Rosenwald, the successful businessman who was also benefactor for African American education in the South.'

Published on August 21, 2015 20:57

"Strange Fruit"-- Choreography by Pearl Primus; Performance by Dawn Marie Watson

Inspired by the lyrics of

Lewis Allan

(Abel Meeropol) that were famously brought to life by Billie Holiday, this is the choreography of dancer and scholar

Pearl Primus

, performed by Philadanco's Dawn Marie Watson.

Inspired by the lyrics of

Lewis Allan

(Abel Meeropol) that were famously brought to life by Billie Holiday, this is the choreography of dancer and scholar

Pearl Primus

, performed by Philadanco's Dawn Marie Watson.

Published on August 21, 2015 20:36

Large Professor: 'I Really Live Through This Music'

Published on August 21, 2015 04:00

Has Larry Wilmore's 'Nightly Show' Has Found Its Voice?

NPR profiles Larry Wilmore on the occasion of the 100th episode of his Nightly Show. On his willingness to talk openly about race, Wilmore says "The fact that we live in a world where black people have to strategize so they're not brutalized by police is insane."

NPR profiles Larry Wilmore on the occasion of the 100th episode of his Nightly Show. On his willingness to talk openly about race, Wilmore says "The fact that we live in a world where black people have to strategize so they're not brutalized by police is insane."

Published on August 21, 2015 03:55

August 20, 2015

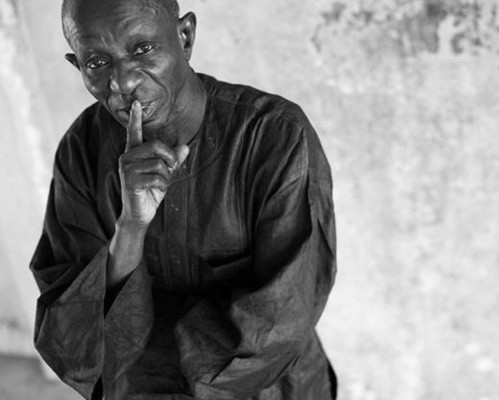

Remembering Senegalese Master Drummer Doudou Ndiaye Rose

'In Senegal, Doudou Ndiaye Rose (1930-2015) was considered a master drummer and was recruited to play with serious artists who wanted his drum — the sabar — in their work. Musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, the Rolling Stones and Josephine Baker all called on Rose.' -- +Public Radio International (PRI)

'In Senegal, Doudou Ndiaye Rose (1930-2015) was considered a master drummer and was recruited to play with serious artists who wanted his drum — the sabar — in their work. Musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, the Rolling Stones and Josephine Baker all called on Rose.' -- +Public Radio International (PRI)

Published on August 20, 2015 20:57

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.