Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 703

August 26, 2015

The Global African: Football Player Turned Street Artist Aaron Maybin

'Aaron Maybin is an athlete turned street artist that captures black life in a unique and creative way. On this segment, Bill Fletcher of +The Global African talks to Maybin about his craft, his transition from the NFL, and the importance of street art. The Global African also examines the 1st annual Movement for Black Lives conference in Cleveland, Ohio.'

'Aaron Maybin is an athlete turned street artist that captures black life in a unique and creative way. On this segment, Bill Fletcher of +The Global African talks to Maybin about his craft, his transition from the NFL, and the importance of street art. The Global African also examines the 1st annual Movement for Black Lives conference in Cleveland, Ohio.'

Published on August 26, 2015 20:05

When What’s Straight is Really Crooked Too: A Strange Review of “Straight Outta Compton

“When What’s Straight is Really Crooked Too: A Strange Review of “Straight Outta Compton”by Stephane Dunn | @DrStephaneDunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“When What’s Straight is Really Crooked Too: A Strange Review of “Straight Outta Compton”by Stephane Dunn | @DrStephaneDunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile) As Ren says, "she deserved it – bitch deserved it." Eazy agrees: "Yeah, bitch had it coming."People talk all this shit, but you know, somebody fucks with me, I'm gonna fuck with them. I just did it, you know. Ain't nothing you can do now by talking about it. It ain’t no big thing – I just threw her through a door” -- Dr Dre ["Beating Up the Charts," Rolling Stone 1991]Let me keep it very real from the onset. When I’m driving down the street and the throwback Hip Hop station plays that Straight Outta Compton or say Dre’s “Chronic,” I bump it. Loud. [the little one isn’t in the car, of course].

It can be Aftermath or Cube’s hard hitting, genius NWA diss spun in the aftermath of his departure from the group. I’m turning it up, my lips are going to move, and I’m waving arms, nodding my head, even my hips are trying, and don’t let it be summer time on a hot sunny day. The sunroof’s opening and the windows gotta go down. It’s N.W.A and for a few minutes I’m going back to the day. But let me drop something else real – as much as it may trouble my nostalgia, my kinship to some hard bruhs, there’s another soundtrack, yeah, in my head but still no less compelling, drumming loud and furious against Dre’s irresistible beats, Cube’s dangerous lyrics and that Eazy E’s seductive gangsta drawl. It’s not new. I’ve always had complicated N.W.A love cause I never did, never could love “A Bitch Iz a Bitch.”

The hit in my head always pushed back though it wasn’t reflected in popular radio play and never went platinum and won’t ever receive enough serious media hype or public engagement from N.W.A-movie loving-Hip Hop head-black folk or the American mainstream. The subject’s a sensationalist aside, that hint of scandal that hypes movie and icon buzz. It’s been on mind heavy with the release of the F. Gary Gray directed, Straight Outta Compton.

Straight outta Compton, balls hung low, Dre, Cube Eazy E and Old Yella too, got the club bumping and the street jumping, -F – the Police and women too . . .smack a Bitch, jack a bitch, screw ‘em all . . . they just bitches, bare asses, swinging tits, holes and hoes, a lucky ride or die chick or two, no Dee Barnes, JJ Fad, Tairrie B. not even Michel’le

Yeah, yeah, I know, obviously I’m no songwriter, no rap lyricist. I am a sista writer with a triple consciousness, a simultaneously glorious, bothersome, womaness and blackness informing humanness. I am a woman struggling to theorize about a hit movie, an important American story that doesn’t make it to the Regal or AMC but every so often, a movie that looks good and does some fine Hollywood storytelling with killer, on point casting that’ll have the most devoted N.W.A fan double taking and believing the whole way through the movie.

‘I gotta see it’ but ‘I don’t want to invest in some patriarchal shit,’ I debated internally. I could be like the hordes of black men who proudly declare they didn’t see Precious or The Color Purple cause they feed into dominant narratives about the dysfunction of black men and it don’t matter whether the director is Lee Daniels or a Steven Spielberg or whether the movie or story is told compellingly or not I too could quietly boycott. But how could I bear witness and deal with my complicated N.W.A, rap music love and nostalgia if I didn’t?

Luckily, when I did go see Straight Outta of Compton, anticipating those beats, I could thank F. Gary Gray for letting the first off the chain scene remind my un-video girl-gyrating, never-been-a Bitch-ass, not to sit there totally nodding, grinning, swaying and lip syncing on cue merely indulging in the hype. Two dealers, one Eazy E. meet in a crack house; they get past the bad ‘nigga’ posting up and posturing but before they can complete business, the LAPD, swat, and presumably all of California law enforcement move on the house and bust it down like it’s a den of terrorists plotting the destruction of the U.SA.

It’s the women who primarily populate the House. When the scene gets hot, Eazy running and trying to bust out anyway he can, mows down a black woman – who isn’t even trying to run but doing ride-or-die chick duty and getting rid of the stuff as ordered by the Man of the house. It’s a quick shot, so quick you could miss it, and especially of course the sequence is about Eazy and the camera is concerned with his body and hers only as it functions to heighten the alluring spectacle of the scene, the intensity of what’s at stake for Eazy if caught and the element of danger he both personifies, perpetuates, and is victimized by in the streets of Compton. If I had been at home, remote in hand, I would’ve pressed rewind and checked that out again – that was a woman right? Mowed down and just like that dismissed and another woman down in a flash as the cops rush in cocked to kill.

The movie, deftly mixing fact and fiction and shot finely by cinematographer Matthew Libatique, spins an engrossing rags-to-riches tale of five talented ghetto brothers, Dre, Eazy E, Cube, DJ Yella, and MC Ren, who rise from the streets to become iconic and wealthy. Straight Outta of Compton goes there on several key fronts, police brutality for one, no surprise there; the intense prevalence of encounters with the police set up the impact of the birth, performance, and controversy of the group’s most infamous hits, “Fuck tha Police.” The portrait of the cops’ brutal and constant policing of Compton and of specifically young black men is relentless and framed powerfully through the unflinching perspective of the latter.

Straight Outta picks and chooses incidents and chapters from the group’s emergence and demise, as a biopic does. Knowing the highlights of N.W.A history and the lyrical reels of gangsta life written by Cube and beat out by Dre, their struggles with the police, the emergence of gangsta manager, Death Row head Suge Knight, the departure of Cube then Dre, Eazy E’s AIDS diagnosis and death, we fill in some blanks. It checks the financial exploitation of the young Hip Hop stars through the white music executive, and the seemingly benign paternalistic Jewish manager, playing up and complicating the dynamics between Eazy and Jerry Heller, and the rest of the group members.

But here’s where Straight Outta Compton does not go there. For all its emphasis on the daring swagger of its subject [even Minister Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam get a nod in a striking scene], Cube, Dre and Gray stay conventional, play safe, and replicate what a ton of movies by black and white American filmmakers do. They pointedly chose not to deal with the unpopular side of gender problems – male sexism and abuse against women. They don’t delve into their relationships with women in any substantial way and of course any representation of the young men’s negative treatment of women that might trouble or complicate the heroic portrait of the group and its individual members. The most prominent presence of women is via the party scenes featuring the naked, ready to serve women who function to authenticate the group’s street cred and heterosexuality masculinity. The violence there helps to heighten the glamour of their survival and exists for Eazy E only as a necessary requirement of hood survival, Cube only when necessary possibly to get his hard earned money and stand up for himself, and Dre in extreme cases – nobly protecting his little brother.

The film instead presents a Dre who, if anything, appears disgusted by violence. His frustration with life and the struggle comes out in the beats and in moments where he polices the violence and the accesses of others that distract from the purity of the music making process. From the first shot of Dre lying on the floor immersed in sound and wax, the film casts him as a thoughtful genius artist, the mythical, mystical beast master. Suge Knight, of course, easily serves as a convenient Bogeyman. His extreme brutishness sanitizes Dre more.

In ignoring Dre’s well-publicized assault on Dee Barnes, his abuse of former girlfriend, music collaborator, and mother of his son, Michel’le, rapper Tairrie B. and the misogynistic implications of the music, Straight Outta of Compton reinforces the idea that the societal exploitation, victimization, and abuse of black men and the historical exploitation of black music artists is worth screen time and essential to any tru-ish story of black men’s journey up, but not the women who are mostly, even at a glimpse, troublesome mothers, unsupportive baby mamas, party hoes, or those ride or die chicks and eye candy. It is evidently not real or gangsta glorious to direct a complicated self-gaze and forge any serious critique at all on violence against women or misogyny.

In a scene near the film’s end, we get one of the most important chapters of the five young men’s history together. Eazy finds out he’s dying; his pregnant partner is by his side [yeah I already knew she and the baby tested negative], but there isn’t a second of screen time given to a moment of just the two together dealing with the heavy weight of it all. Instead she’s muted though of course devoted.

And women inside the film and beyond are used to this lie that the cinema has projected – that the women aren’t part of the real story or important save for in marginalized, safe ways, to who and where these men have been, and that no attention need be paid to any social, physical, or emotional damage on women that the male heroes inflicted because they accomplished something worthwhile, sexy, historical, ‘cause they made it up and out and were badass in the face of police brutality and discrimination.

So while “F- tha Police” resonates with me when I think of Michael Brown, Eric Garner . . . of Sandra Bland, Michel’le’s voice from a recent interview with DJ Vlad plays on the flip side: “That’s Cube’s version of his life . . . Why would Dre put me in it . . . cause if they start from where they start from, I was just a quiet girlfriend who got beat on and told to sit down and shut up .”

Straight Outta Compton really spins such a good looking, up-from-the-hood confirmation of the masculine bravado we associate with N.W.A and the music, that it invites us to be satisfied with the thrilling highlights, ignore and not interrogate the not so small blanks and unexplored territory in the biopic.

In “Here's What's Missing From Straight Outta Compton: Me and the Other Women Dr. Dre Beat Up,” Dee Barnes, a woman intimately acquainted with Dr. Dre’s not so mystical fists sums it up: Accurately articulating the frustrations of young black men being constantly harassed by the cops is at Straight Outta Compton’s activistic core. There is a direct connection between the oppression of black men and the violence perpetrated by black men against black women. It is a cycle of victimization and reenactment of violence that is rooted in racism and perpetuated by patriarchy. If the breadth of N.W.A.’s lyrical subject matter was guided by a certain logic, though, it was clearly a caustic logic.

These days in the glare of Straight Outta Compton's success and the murmurs about his violent behavior with women in the media, Dre is apologetic. But he could have done something much more meaningful and not only apologized but did work towards helping to eradicate the romanticization of violence against women in Hip Hop and beyond it. That requires a different kind of swagger, a transformative kind of authenticity. Dre could have fought to drop that heavy beat on the screen and kept it real. Perhaps then we could have witnessed and applauded his self-evolution and not just materially.

+++

Stephane Dunn, PhD, is a writer who directs the Cinema, Television, & Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College. She teaches film, creative writing, and literature. She is the author of the 2008 book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films (U of Illinois Press). Her writings have appeared in Ms., The Chronicle of Higher Education, TheRoot.com, AJC, CNN.com, and Best African American Essays, among others. Her recent work includes the Bronze Lens-Georgia Lottery Lights, Camera Georgia winning short film Fight for Hope and book chapters exploring representation in Tyler Perry's films. Follow her on Twitter: @DrStephaneDunn

Published on August 26, 2015 19:56

The Illusive Conversation: Race in America’s Classrooms by David J. Leonard |

The Illusive Conversation: Race in America’s Classroomsby David J. Leonard | @DrDavidJLeonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The Illusive Conversation: Race in America’s Classroomsby David J. Leonard | @DrDavidJLeonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)In the aftermath of the savage murder of 9 African American men and women in Charleston, SC there was lots of public discussion of America’s unresolved racial acrimony. In the wake of Rachel Dolezal, there were daily debates about privilege, identity, and the unresolved issues of race in America.

In the days following uprisings in Baltimore and Ferguson, and the brutal attack of Dajerria Becton in McKinney, and the killing of Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Sandra Bland, Sam Dubose, Christian Taylor there were a slew of articles and public discussions of police violence, poverty, segregation, and America’s continued racial divide.

You would think from these recent events, times-were-a-changing; that long overdue talk was going to finally happen. If this conversation is happening, the revolution has not reached America’s colleges and universities.

While colleges and universities have never fully invested in African American Studies, and Ethnic Studies, the most recent budget crisis has led to tightened budgets, divestment, and a lack of growth. Irrespective of the “calls for yet another conversation about race,” and the persistence of racial inequities, addressing racism on and off campus has not been a priority. State legislatures across the nation responded to the purported STEM crisis with a steady stream of investment; The crises of poverty, police violence, housing and employment discrimination, and systemic anti-Black racism has not compelled investment.

The ‘racial strife’ and tension the news media spotlights has not led to widespread support of new faculty to foster these necessary racial conversations; no financial investment in departments committed to developing curriculum to prepare the next generation of students to be racially literate. In a moment where the needs couldn’t be clearer, colleges and universities have prioritized recreation facilities, athletics, bloated administrative costs, and professional programs.

If you had any hope that higher education will see the writing on America’s racial wall,, look no further than the cases of Steven Salaita, Saida Grundy, Shannon Gibney, Zandria Robinson, Brittney Cooper, Chandra Prescod-Weinstein and others outside the news cycle. The hostility and opposition is daily, impacting tenure and promotion, retention, and the overall experiences of faculty of color.

“Things that were previously simple are not so easy to explain anymore. We’ve metaphorically moved ‘from simple addition to calculus’ in the study of social sciences,” notes Safiya U. Noble, assistant professor in the Department of Information Studies in the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies at University of California, Los Angeles. “Yet, I am doubtful that my counterparts in the math department have to employ the kind of pedagogical strategies we do, as Black women faculty in the social sciences and humanities, to have students comprehend the research and accept it from us as legitimate experts.”

Upon teaching her first general education course, Whitney Battle-Baptiste, an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at University of Massachusetts Amherst, spoke of a loss of innocence for teaching about race: “I was met with hostility, anger, fear as well as excitement and enthusiasm. Those feelings came through in my evaluations, with references such as, I was too political, brought up too much about race and inequality; my approach to teaching was elitist and angry.”

The level of racial hostility and white student resistance for all things racial can be seen in the faculty evaluations. Resembling an online comment section and Twitter, evaluations are rife with racism and sexism. Countless studies have documented how racism and sexism shape the classroom and infect evaluations. Black faculty members are routinely criticized for being “hostile,” “angry” and “unprofessional.” Claims of bias and critiques lamenting the focus on race and racism, despite that being the theme of the course, are commonplace.

The recent events in Ferguson, Charleston, Baltimore, Texas, and elsewhere make clear the stakes and the importance of this work. It highlights the necessity of racial literacy, diversity, critical multicultural education, and ethnic studies. It points to the importance of dealing with whiteness. According to Stephany Spaulding, “Without Critical Whiteness Studies, we will continue living in a society that blindly privileges particular ways of organizing institutional practices and structures.”

From the lack of investment in creating diverse places of learning, to the open hostility directed at the faculty, particularly women of color, to the rampant racial complacency from white America and its liberal institutions of advanced thinking and learning, it is clear that colleges and universities are not well-positioned to address the problem of the twenty-first century: Racism.

The question remains will colleges and universities seize upon these opportunities? Will the public at large grab hold of this moment? Will white faculty and students demand not only conversations about race, but a financial and cultural investment, and institutional change? Or will colleges and universities refuse the responsibility to provide those ill-equipped to have these conversation with the necessary tools?+++

David J. Leonard is Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. Leonard's latest books include After Artest: The NBA and the Assault on Blackness (SUNY Press), African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (Praeger Press) co-edited with Lisa Guerrero and Beyond Hate: White Power and Popular Culture with C. Richard King. He is currently working on a book Presumed Innocence: White Mass Shooters in the Era of Trayvon about gun violence in America. You can follow him on Twitter at @drdavidjleonard.

Published on August 26, 2015 10:01

August 25, 2015

Study Tracks Vast Racial Gap In School Discipline In 13 Southern States

A new study from Edward J. Smith and Shaun R. Harper shows that "Nationally, 1.2 million Black students were suspended from K-12 public schools in a single academic year – 55% of those suspensions occurred in 13 Southern states....Despite comprising only 20.9% of students in the 3,022 districts analyzed, Blacks were suspended and expelled at disproportionately high rates."

A new study from Edward J. Smith and Shaun R. Harper shows that "Nationally, 1.2 million Black students were suspended from K-12 public schools in a single academic year – 55% of those suspensions occurred in 13 Southern states....Despite comprising only 20.9% of students in the 3,022 districts analyzed, Blacks were suspended and expelled at disproportionately high rates."

Published on August 25, 2015 20:04

PBS NewsHour: Writer Jesmyn Ward Reflects on Survival Since Katrina

'After writer and Tulane University professor Jesmyn Ward survived Hurricane Katrina while staying at her grandmother’s house, she wrote Salvage the Bones, an award-winning novel about a Mississippi family in the days leading up to the devastating storm. She joins Gwen Ifill to discuss how the storm affected the rural poor who could not escape, and now, who may not be able to return.' -- +PBS NewsHour

'After writer and Tulane University professor Jesmyn Ward survived Hurricane Katrina while staying at her grandmother’s house, she wrote Salvage the Bones, an award-winning novel about a Mississippi family in the days leading up to the devastating storm. She joins Gwen Ifill to discuss how the storm affected the rural poor who could not escape, and now, who may not be able to return.' -- +PBS NewsHour

Published on August 25, 2015 05:40

"Lean In" -- Music + Visuals from Lizz Wright

Music and visuals from "Lean In", the lead single from Freedom & Surrender, Lizz Wright's new album on the Concord Jazz label.

Music and visuals from "Lean In", the lead single from Freedom & Surrender, Lizz Wright's new album on the Concord Jazz label.

Published on August 25, 2015 05:28

Black Lives Matter Movement Makes Impact in Brazil

Published on August 25, 2015 04:41

August 23, 2015

Big Think: Black Mental Health Isn't the Same as White Mental Health

'+Big Think and the Mental Health Channel presents Big Thinkers on Mental Health, a new series dedicated to open discussion of anxiety, depression, and the many other psychological disorders that affect millions worldwide. In this episode, Dr. Michael Lindsey of NYU's Silver School of Social Work sees signs of debilitating trauma throughout black America. He points to two key reasons this is.'

'+Big Think and the Mental Health Channel presents Big Thinkers on Mental Health, a new series dedicated to open discussion of anxiety, depression, and the many other psychological disorders that affect millions worldwide. In this episode, Dr. Michael Lindsey of NYU's Silver School of Social Work sees signs of debilitating trauma throughout black America. He points to two key reasons this is.'

Published on August 23, 2015 20:30

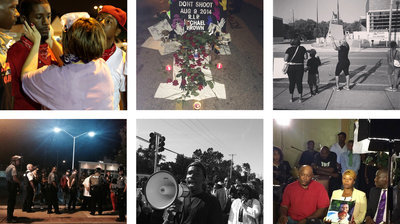

Gene Demby: How Black Reporters Report On Black Death

"As calls for newsroom diversity get louder, NPR's Gene Demby suggests, we might do well to consider that Black reporters covering race and policing literally have skin in the game."

"As calls for newsroom diversity get louder, NPR's Gene Demby suggests, we might do well to consider that Black reporters covering race and policing literally have skin in the game."

Published on August 23, 2015 20:21

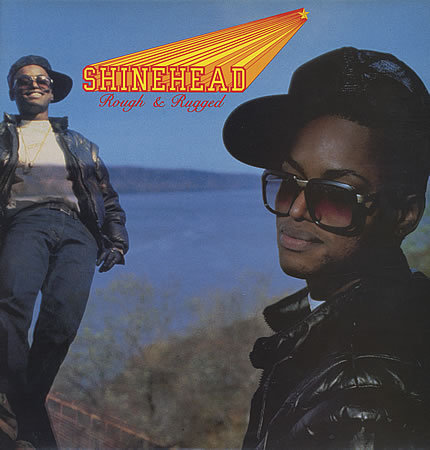

Michael v.: Shinehead--"Billie Jean"

Published on August 23, 2015 16:29

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.