Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 686

October 23, 2015

Talks at the Schomburg: Carole Byard, the Rent Series, and Beyond

'+Schomburg Center celebrates the work of visual artist Carole Byard with a conversation addressing her “Rent Series.” The program centers on Byard’s discovery--after her father’s death--of a cache of rent receipts he’d kept in his life-long efforts to provide housing for their family, always struggling to do so. In the early 1980s, Byard set about to reimagine her father efforts in a series of images which she titled “Rent.” Listen to Byard’s peers discuss her work.'

'+Schomburg Center celebrates the work of visual artist Carole Byard with a conversation addressing her “Rent Series.” The program centers on Byard’s discovery--after her father’s death--of a cache of rent receipts he’d kept in his life-long efforts to provide housing for their family, always struggling to do so. In the early 1980s, Byard set about to reimagine her father efforts in a series of images which she titled “Rent.” Listen to Byard’s peers discuss her work.'

Published on October 23, 2015 04:24

October 22, 2015

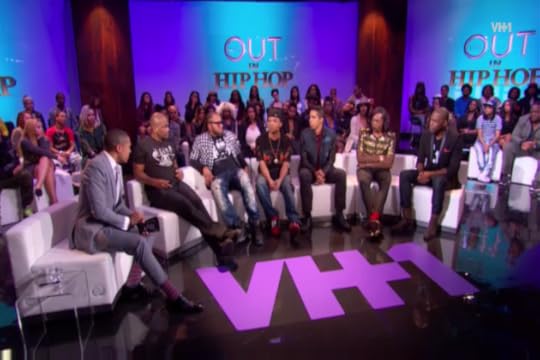

Out in Hip-Hop, But Where is the R & B?! by Jeffrey Q. McCune

Out in Hip-Hop, But Where is the R & B?!by Jeffrey Q. McCune | @DrJeffrey2U | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Out in Hip-Hop, But Where is the R & B?!by Jeffrey Q. McCune | @DrJeffrey2U | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)The VH1 special, Out in Hip-Hop with TJ Holmes, left me with questions: Are there black same-gender loving men who do not hide behind a swizz beat or a B-3 Hammond? Are black gay men always beholden to the black church and its brother hip-hop?!

Watching Out in Hip-Hop left me thinking that these questions were a done deal. Until I began to think about the many men whose anthems were sung by Luther Vandross, Sylvester, Frank Ocean, Frankie Knuckles, and even Ms. Frieda. As Karamu Brown, of The Real World kept emphasizing, we must never forget the ways in which the black gay community has affirmed itself, loved itself, made it’s own music, and moved beyond the pews and the “pimp juice.”

What do we gain by thinking about the forgotten R & B Brothers? We gain an understanding of a community anchored in love, searching for love, and always beholden to love. In the face of homelessness, exile, HIV/AIDS, and anti-black violence, black gay brothers (and sisters, for that matter), have to find their way out. R & B, house, bounce, or even gay-affirming hip-hop just may offer such refuge.

Growing up, I recall my parents listening to Luther Vandross’ “A House is Not a Home,” making me grateful for the type of “be yourself wherever you go” space which made me safe at home, even as it housed the subtle homo-antagonisms hidden nicely in scriptural reference and common brotherly policing. I remember the proclamation of “Divas to the dance floor!” at my first gay club, which became a house music anthem of revolt and revolution for the South Side Chicago kids who traveled “up north,” to get their taste of something beyond concrete anthems and gospel medleys.

I also remember turning from the hip-hop station, as I sat in the car of the man whose name would forever be a part of my history; seeking to feel comfortable for every internal feeling in my 19-year old body. These reflections remind me that my masculinity and sense of self was never built on the sinking sand of the same ol same, but rather a rich collage of rhythmic riches which taught me how to be.

Out in Hip-Hop forgot these stories; leaving us to believe that hip-hop and the black church were the only frames through which to see our world; the only survival mechanisms for these black children living “in the life.”

Nonetheless, as Pastor Delman Coates told us, these out of context scriptures have packed a real punch in the lives of black gay men, right along with the hip-hop hymns which dawn every anti-gay slur possible. The black church has become a kissing cousin to it’s use-to-be-nemesis hip-hop, as it continues to use texts to exile brothers and sisters, while at the same time using their labor and claiming to love. For this reason, it makes no sense to believe that black LGBT folks are not finding other ways to celebrate themselves: either by hearing the hip-hop and church hymns differently than their straight counterparts, or moving away from them all together.

Cause if the truth is to be told, many black gay men heard LiL Wayne’s “ He so sweet…wanna lick the wrapper” too and created a bromance of their own. For us, the “she” pronoun was muted and we were left to engage in the fantasies we had come to know as a necessary response, to sister or brother so & so at church who made us answer the “who are you dating” question.

Avoiding this daunting, presumptuous, and often irritating question meant going to other spaces and sources to affirm the love which “dare not speak it’s name.” It is this commitment to love that music like R & B illuminates, offering a site of potential connection which hip-hop just can’t facilitate with it’s multiple ways of telling black LGBT “you are not welcome.” Of course, R & B is no utopia, as we would have to search hard to find explicit lyrics of same-gender love. And yes, there are a few songs in hip-hop—like Young Thug’s “OD”—which speak of showing “love for my partner.” These truths can’t be discounted.

Nonetheless, the texture and Otis Redding like tenderness in R & B provides a musical space of imaginative, creative lovemaking; a real dedication to the erotic, the friendly, and the everyday emotional breadth. The capacity to connect on this love-level cannot be understated, in a world ridden with religious fundamentalism and persecution, anti-black/anti-gay violence, workplace discrimination, school non-accommodation, and the various violences done unto black LGBT folk everyday.

I refuse to believe that the only refuge is the church and it’s hyperbolic cousin hip-hop. While there is mad love in hip-hop, the presence of love in Hip-Hop for black LGBT folk is hard to find. Furthermore, it is hard to believe that everything we know about manhood and womanhood—for those non-LGBT and those who are LGBT—is found in two singular spaces which create all types of havoc in the lives of us all.

What we know for sure—about all who are black, for whom freedom is so fragile—is that we will find routes of escape. So while some sit behind the B-3 Hammond or the hard beat, many black LGBT folk sit in homes they built, where the music and melody more often seems to include them, or at least invite them. These folks are finding their way out of Hip-Hop, all while others navigate being out in Hip-Hop.

+++

Jeffrey Q. McCune, Jr. is the author of Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing (2014). He is an Associate Professor of Gender Studies at Washington University-St Louis, an activist, and Pastor-elect at Liberation Christian Church in St. Louis , MO.

Published on October 22, 2015 21:59

#FeesMustFall : South African Students at Wits University Protest Against Increases

'As the #NationalShutDown continues in South Africa, Wits University students voice their opinions on rising tuition rates with #WitsFeesMustFall' -- +Independent Online

'As the #NationalShutDown continues in South Africa, Wits University students voice their opinions on rising tuition rates with #WitsFeesMustFall' -- +Independent Online

Published on October 22, 2015 12:21

Did You Know? Black Girls + School Suspension Rates

FACT: Black girls are six times as likely to be suspended in our nation's public schools as white girls. All Black youth are at risk of being pushed onto the school-to-prison pipeline.

Take a stand against the barriers to equality facing our girls! Join us October 23 at 12:00PM EST for a virtual town hall.

#WhyWeCantWait: Where Do We Go From Here?Demarginalizing women and girls of color and creating an intersectional social justice agenda

FACT: Black girls are six times as likely to be suspended in our nation's public schools as white girls. All Black youth are at risk of being pushed onto the school-to-prison pipeline.

Take a stand against the barriers to equality facing our girls! Join us October 23 at 12:00PM EST for a virtual town hall.

#WhyWeCantWait: Where Do We Go From Here?Demarginalizing women and girls of color and creating an intersectional social justice agenda

Published on October 22, 2015 06:00

October 21, 2015

European Powers, Islamic Movements, and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

'In the 18th century, Senegambia was bitterly contested by France and Great Britain for its slave-trading. But a third power, the Islamic theocracy of Futa Toro, rose to prominence and opposed both foreign powers while seeking to put an end to the slave trade and slavery. Watch highlights from the fascinating conversation with Christopher L. Brown, Professor of History at Columbia University, and Rudolph Ware, Associate Professor at the University of Michigan, about this intricate story.' -- +Schomburg Center

'In the 18th century, Senegambia was bitterly contested by France and Great Britain for its slave-trading. But a third power, the Islamic theocracy of Futa Toro, rose to prominence and opposed both foreign powers while seeking to put an end to the slave trade and slavery. Watch highlights from the fascinating conversation with Christopher L. Brown, Professor of History at Columbia University, and Rudolph Ware, Associate Professor at the University of Michigan, about this intricate story.' -- +Schomburg Center

Published on October 21, 2015 19:00

An African American from Compton is a Rising Star on the Mexican Music Scene

'Rhyan Lowery is a 19-year-old African American from Compton, but he grew up listening to Mexican regional music — corridos, banda and cumbia. So it’s no surprise he loves some of those signature sounds.'

'Rhyan Lowery is a 19-year-old African American from Compton, but he grew up listening to Mexican regional music — corridos, banda and cumbia. So it’s no surprise he loves some of those signature sounds.'

Published on October 21, 2015 18:44

Lawsuits Target 'Debtors' Prisons' Across the Country

'Since September, six lawsuits were filed against New Orleans; Nashville, Tenn.; Biloxi and Jackson, Miss.; Benton County, Wash.; and Alexander City, Ala in response to Debtors Prisons. In the past year, lawyers have also won settlements that have forced courts to change practices in Montgomery, Ala.; DeKalb County, Ga.; and St. Louis County, Mo.'

'Since September, six lawsuits were filed against New Orleans; Nashville, Tenn.; Biloxi and Jackson, Miss.; Benton County, Wash.; and Alexander City, Ala in response to Debtors Prisons. In the past year, lawyers have also won settlements that have forced courts to change practices in Montgomery, Ala.; DeKalb County, Ga.; and St. Louis County, Mo.'

Published on October 21, 2015 18:35

Left of Black S6:E6: The Women of the UNIA; The Women of #BlackLivesMatter

Left of Black S6:E6: The Women of the UNIA; The Women of #BlackLivesMatter

Left of Black S6:E6: The Women of the UNIA; The Women of #BlackLivesMatterLeft of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined on location at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania by Natanya Duncan (@GarveyiteWomen), Assistant Professor of History and Africana Studies at Lehigh University.

Neal and Duncan discuss the under-studied role of Black women in the organizing efforts of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Organization (UNIA), particularly in the organization’s branches in the deep South, the role of Black women in the Movement for Black Lives and the myth that #BlackLivesMatter lacks leadership.Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on October 21, 2015 15:05

Kendrick Lamar and the National Symphony Orchestra: 'These Walls'

'On October 20, 2015, Kendrick Lamar and the National Symphony Orchestra Pops delivered a one-night-only performance at The Kennedy Center featuring some of Lamar's biggest hits and cuts from his lyrical masterpiece “To Pimp a Butterfly”'

'On October 20, 2015, Kendrick Lamar and the National Symphony Orchestra Pops delivered a one-night-only performance at The Kennedy Center featuring some of Lamar's biggest hits and cuts from his lyrical masterpiece “To Pimp a Butterfly”'

Published on October 21, 2015 12:39

And 12 Years More: The Enduring Legacies of Slavery in America

And 12 Years More: The Enduring Legacies of Slavery in Americaby Lawrence Ware | @Law_ Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

And 12 Years More: The Enduring Legacies of Slavery in Americaby Lawrence Ware | @Law_ Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Two years ago I sat in an almost empty auditorium waiting for 12 Years a Slave to begin. To my right, with an obligatory seat between us per the unspoken yet ubiquitous norm known as ‘man law,’ was my dear friend and brother T. E. Dancy. We arrived prepared to critically engage the film as scholars, but we underestimated the impact the film would have upon us emotionally.

Every year I screen the film on campus. I am consistently surprised by how few have seen it. They have seen movies detailing the horrors of the holocaust. They have watched violent visual narratives about the war on terror. Yet, for some reason, this film remains unseen.

White Americans have a complex relationship with the history of black people in this country. They intellectually assent to the proposition that slavery happened. They admit that it was ‘bad.’ Yet, like attempts to minimize the horror of slavery in Texas textbooks, white folks don’t want to be confronted with the lived experiences of slaves.

Black Americans don’t have that luxury. As Ta-Nehisi Coates argued, even if attempts are made to ignore the past, the shadow of slavery follows black people today. In our language, in our food, in the construction of American social institutions upon the assumption that if you inhabit a black body you possess less personhood than if you inhabited a white body, the history of slavery still shapes black life in America.

As I discussed the film with T. E. Dancy, I began to realize that this visual text powerfully communicates these truths in four ways.

Socioeconomic status is no exception from racial realities

Solomon Northup was an educated, cultured free black man in the 1840s. His only mistake was thinking that being born free meant he was safe from the ugliest manifestation of white supremacy in American history. Yes, he was educated; yes, he was musically talented; yes, he was petite bourgeoisie; no, that did not matter. One’s black body is always a threatened when living under white, capitalistic hegemony.

This remains true today.

As black folks in America gain greater levels of economic upward mobility, there is a temptation to think that since some of us live in mostly white neighborhoods and have gained access to mostly white schools, then we are living in a post-racial society. This simply is not true. Being black means that you are disproportionately at risk to living in poverty and that you have a higher chance of being incarcerated at some point in your life. That was true in the 1840s and remains true today.

Indifference to black suffering

In a powerful scene halfway through the film, Solomon Northup is hung from a tree by his neck just low enough for his toes to reach the ground beneath. Director Steve McQueen shows this in an extended take. While watching a man hang from a noose is disturbing enough, it is what happens in the background that is truly horrifying. Children play, adults engage in business as usual, and we see the aforetime occasionally benevolent white mistress of the house look on casually. This inhumane treatment is not uncommon—in fact, it is the norm.

Again, this remains true today.

We have become desensitized to the suffering of others. Black and brown people live in a seemingly unending state of emergency. Schools are underfunded; access to adequate healthcare is limited; and acts of violence against women of color are ignored while acts of violence against white women are used catalysts for reform. We cannot allow ourselves to become desensitized to human misery; we must remain outraged by all human suffering—not just those cases the dominant culture consider to be important.

Black Stories are Possible

12 Years a Slave shows that one can make a compelling film about race without marginalizing black characters and making a white person's moral outrage the driving force behind the narrative conflict. In the past, movies like Amistad, The Help, and Mississippi Burning have told black stories by focusing on white characters. In this film, the social dynamics of black characters are the focus while white characters are relegated to supporting roles.

For once, the conscious of a good white person isn't the dramatic center of a movie about racism. This movie is not about white people saving the helpless, hapless slaves, but about the lived experience of human beings suffering under an oppressive and brutishly dehumanizing system. I hope this eventually translates into films about black and brown people that are not centered historical injustices.

Black and brown people laugh, cry, and love. Up until now, however, most of the prominent films financed by major studios about people of color are either historical retellings of fights against racism or comedy-dramas that take place in an urban milieu where black stereotypes serve as substitutes for character development (Tyler Perry) or in an upper middle class world where race is all but ignored (again, Tyler Perry).

Black stories are human stories. Films like Pariah and Fruitvale Station show us that, if given a chance, black filmmakers have compelling stories to tell that speak to the universal human experience without referencing a historical moment or making white people the moral center of the narrative. The fact that Patricia Arquette received accolades for her tepid performance in Boyhood while powerhouse performances like GuGu Mbatha-Raw in Beyond the Lights went unnoticed speaks to bias in the industry.

The success of shows like Empire, American Crime, and Black-ish show the breadth of stories possible. I hope movie studies take notice soon.

Racism takes a vicious toll on black bodies

Many were critical of the depiction of violence suffered by slaves. Certainly McQueen did not have to show the flesh falling off the back of Patsey as she is whipped, they declared. I find this sentiment problematic.

Americans have tried to hide the physical consequences of white supremacy for too long. As Ta-Nahisi Coates commented:

“…all our phrasing—race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy—serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this. You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regressions all land, with great violence, upon the body.”

Slavery was an evil system, and the physical toll of those living under this system was horrific. Having read the book upon which the film is based, I am not surprised by what many claimed was McQueen’s gratuitous use of violence; I am taken aback by his restraint. What McQueen does not show are scenes of children being whipped and raped. He does not subject the viewer to examples of indiscriminate killings at the hands of white slave-owners. Indeed, McQueen could be criticized for not showing more.

Similarly, black and brown victims of police brutality often go ignored if these incidents are not caught on camera. Part of the aversion to seeing and sharing these images stems from the longstanding American tradition of ignoring the physical toll of white supremacy on black and brown bodies. As uncomfortable as it may be, we need to come to terms with the fact that systemic racism is not a metaphysical apparition haunting America. It is a real threat to the lives of oppressed people living in this country.

12 Years a Slave is a beautiful, horrifying film. It forces us to examine one of the darkest parts of American history in an unsentimental and unflinching manner. It taught me much two years ago. In light of the contemporary crisis in black America—it teaches me still.

+++

Lawrence Ware is a professor of philosophy and diversity coordinator for Oklahoma State University’s Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to the publication The Democratic Left and contributing editor of the progressive publication RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race for the HuffPost Live, CNN, and NPR.

Published on October 21, 2015 08:29

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.