Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 682

October 31, 2015

What Does Black Freedom Look Like?

Duke PhotographyOn this episode of Left of Black on The Root Jasmine Nichole Cobb talk about her new book,

Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century

(NYU Press). Cobb is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies, and African and African American Studies at Duke University.

Duke PhotographyOn this episode of Left of Black on The Root Jasmine Nichole Cobb talk about her new book,

Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century

(NYU Press). Cobb is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies, and African and African American Studies at Duke University.

Published on October 31, 2015 11:25

October 30, 2015

New Series--Evoking the Mulatto: It's Not a Cool Word [Episode One]

'Created by Lindsay C. Harris, Evoking the Mulatto is a transmedia project exploring black mixed identity in the 21st century, through the lens of the history of racial classification in the United States.' -- +NBPC

'Created by Lindsay C. Harris, Evoking the Mulatto is a transmedia project exploring black mixed identity in the 21st century, through the lens of the history of racial classification in the United States.' -- +NBPC

Published on October 30, 2015 19:42

We Care More About Disciplining Black Girls in Our Schools Than We Do About Their Mental Health

We Care More About Disciplining Black Girls in Our Schools Than We Do About Their Mental Healthby Rebecca Martinez | @BeckyGMartinez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

We Care More About Disciplining Black Girls in Our Schools Than We Do About Their Mental Healthby Rebecca Martinez | @BeckyGMartinez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Spring Valley High School police officer Ben Fields was just terminated for picking up 16 year-old young Black student out of her chair and throwing her against a wall. He was called into the classroom to deal with a student who was said to be disruptive. It is still not exactly clear what she was accused of doing, but some accounts are that she was chewing gum, texting on her phone, and not participating in class.

Another Black student, Niya Kenney, who came to her classmate’s defense, stated that she wasn’t doing anything but sitting quietly in her chair. Niya was also arrested (and released on $1000 bail) for shouting at the officer assaulting her classmate, praying, and recording the brutality on her phone. Another student who tweeted about the incident and claims to have been in the classroom corroborates this, as does Tony Robinson, another classmate who recorded the original video that went viral. What is clear is that the student was not being physically violent and did not possess a weapon.

So, why was this police officer called into the classroom to deal with a student who was sitting in her chair and whose stoic defiance was seen as disruptive? Why wasn’t a school psychologist called in instead? According to the Spring Valley High School website, they have a school psychologist on staff. Given these resources, why are they, and indeed many schools nationally, relying on police to discipline students?

We have seen an uptick, especially with school shootings, in the systemic implementation of embedding police in schools. Combine that with the fact that Black children in schools face disproportionate disciplining compared to white children, and we have the perfect storm of policing and racism in a place of learning. For example, a recent piece in Salon notes that,

For poor children of color, the mouth of the school-to-prison pipeline is manned by police officers who have in recent decades proliferated in districts nationwide. The mass deployment of schools cops, commonly referred to as “school resource officers,” has been made without careful thought or research. And it has produced horrible outcomes.Moreover, citing Justin Nance, a professor at the University of Florida Levin College of Law, the article goes on to state:“From a cost-benefit standpoint, the benefits of having SROs in schools, if any, are unclear; yet, the costs are high – they are expensive to hire, they impede school climate in many schools; and SROs are linked to having more students involved in the justice system.”And, as Brittney Cooper argues, one of those horrible outcomes is that young Black women in our school systems face bias and even violence at the hands of those charged with educating them because they are “guilty of being a black girls.” One result is that Black female students have a suspension rate six times that of white female students.

Given what we know about the racialized school to prison pipeline, let’s rephrase the question asked above: would the school psychologist had been called in instead of police had the student been a white female? A point of clarity: the students knew the officer, who was called in to deal with student, as “Officer Slam.” Many had complained about his targeting Black students. One former student has even filed a complaint that is set to go to court in January.

That he was allowed to be in a school in that capacity deserves another article in and of itself. Reading some of the comments in the first days after the incident, it was striking how some believed that the student’s non-violent behavior and stoicism in the classroom was more disruptive than this police officer being called in. Some weighing in argued that she needed to be removed so that learning could take place. Look, if you think learning was going to happen after the police were called then you need to re-evaluate your logic. This officer had a reputation.

Any administrator or teacher thinking that his presence wasn’t going to result in a truly chaotic disruption doesn’t know what is happening in their own school. Even not knowing this background, it would be incredulous to argue that Ben Fields was less disruptive than the young woman he was called to deal with. And, not only does she have to now deal with the traumatic incident, but so do the students who watched the brutality of a classmate getting tackled and thrown across the room.

Those students later said they were paralyzed with fear. To think they were in a position to learn after she was removed is to have a level of emotional detachment so absolute as to be almost sociopathic. Even if Officer Fields hadn’t acted so brutally, the presence of police in a classroom is more disruptive than a kid with a cellphone. Another question emerges: what of the mental health of this young woman and her classmates?

When I heard this story, I immediately wondered about her circumstances. What might have she been going through that day? Was there something going on in her life? These questions that empathize rather than assume “badness,” is how we should approach understanding the students we ask our schools to teach. Instead, racism, whether overt or unconscious, elicits negative assumptions about attitudes and dispositions for explaining the behaviors of children of color.

It was reported that this young woman was placed into care after the loss of her mother and grandmother. That information was incorrect about the deaths of her mother and grandmother, but it is still not know if she was in foster care. Regardless, it does seem as if she was dealing with something, and if she was in foster care, did the teacher not know this? And if not, why not? This is the type of information that should be passed on by school counselors or social workers. Perhaps she should have even been pre-emptively placed under the care of the school psychologist?

Are schools nationwide investing more in these school resource officers than they are in counselors, social workers, and school psychologists? Do we see a distribution of the former in wealthier white schools and the latter in poorer areas that largely serve children of color? These are the types of questions that we should be asking.

Mental Health of Black Girls and Women

The mental health of Black girls and women often gets overlooked as a serious public health problem. As a result, they are under-diagnosed and receive inadequate treatment. According to the website blackwomenshealth.com,

The rates of mental health problems are higher than average for Black women because of psychological factors that result directly from their experience as Black Americans. These experiences include racism, cultural alienation, and violence and sexual exploitation.

The most common psychological health problems for women of color include depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide. When it comes to adolescent girls of color, they too are being left out of the increasing attention being paid to adolescent mental health with the estimate that 20 percent of children nationally have a diagnosable mental disorder. Adolescent girls, specifically, are more likely to suffer from depression compared to teenage boys.

And while the research is somewhat mixed on the ethnic and racial differences among adolescent girls, there is evidence that girls of color, including African Americans, exhibit more depressive symptoms than their white counterparts. And research indicates that African American women suffer more persistent and severe depression compared to white women, even though they have lower rates (in Psychological Health of Women of Color). When it comes to adolescents, a 2009 study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, found the suicide rate for Black teens has increased dramatically over the last few decades. And, Black female teens, especially, may be at high risk for attempting suicide even if they’re never been diagnosed with a mental disorder. That should send alarm bells ringing.

The classroom is one place where we should be reaching out to Black girls, offering counsel not cops. According to Venus E. Evans-Winters in Teaching Black Girls: Resiliency in Urban Classrooms, “structural influences like institutional racism, sexism, and classism work simultaneously to influence the behaviors and experiences of African American female students (47).” The intersectionality of these systems of oppression means that we have to pay special attention to the different ways in which Black women and girls experience mental health in terms of manifestations, diagnoses, treatments, access to care, and outcomes. Racism, classism, and sexism are built into the structural inequities in our health care system, contributing to this public health neglect.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Police Brutality

The young woman who was brutalized by “Officer Slam” may also have to deal with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) because of this incident. And, not only her, but Niya Kenney, who intervened on her behalf, as well as the other students who witnessed it. The relationship between police brutality and PTSD is not widely studied, but it can be brought on by a variety of traumas. The National Institute of Mental Health characterizes PTSD in the following way:

People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened even when they’re no longer in danger….PTSD develops after a terrifying ordeal that involved physical harm or the threat of physical harm. The person who develops PTSD may have been the one who was harmed, the harm may have happened to a loved one, or the person may have witnessed a harmful event that happened to loved ones or strangers. The Student National Medical Association even came out with a strong statement on PTSD, race and police brutality: We, the members of the SNMA recognize that police brutality threatens the physical, emotional,and psychological health of those involved and should be addressed not only as an issue of social reform, but also as one of public health. The American law enforcement community has historically demonstrated unjust scrutiny against African-American and Latino members of society. This scrutiny has, in turn, led to numerous unmerited physical and psychological attacks upon minorities resulting not only in permanent disability, but also the death of innocent law abiding Americans…. Police brutality and the use of unwarranted physical and emotional force ultimately compromises the physical and mental health of victims and their families while ignoring the need for psychological and social intervention and support of law enforcement officers.

We have to take seriously the potential effects of having police officers embedded in school systems who are more and more relied upon to deal with routine discipline, something for which they are likely inadequately trained. Do we really want to misuse them this way? This is not to say that all officers are reactionary like Officer Fields, but they also are not trained counselors.

Black Girls and Resiliency

At same time, research on Black teen females’ mental health, points to their resiliency. This is known as the adversity-thriving paradox and can help these young women develop a clearer vision of reality having “outsider within status.” In turn this vision makes them capable of struggling against oppression, committing to gender/race social justice, and self and community empowerment. What Niya Kenney did in coming to the aid of her classmate was exhibit that resiliency. But we need to foster the resilience of Black girls; our school systems can be one avenue of opportunity for support if we critically challenge what happens there and demand change. We need to center the caring for Black girls’ well-being rather than reinforcing the school to prison pipeline. One thing is certain: In the words of James Baldwin, “A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him, and a child cannot afford to be fooled.” As to the resiliency, in the words of Kendrick Lamar: “We gone be alright.”

+++Rebecca Martinez is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Women's and Gender Studies at the University of Missouri. She is a medical anthropologist whose research encompasses issues of race, ethnicity, class, gender as related to cancer and reproductive health. Follow her on Twitter: @BeckyGMartinez

Published on October 30, 2015 19:14

How The Mets Found Success In Youth + Discipline + Luck

'NPR looks at how the Mets found success in youth and luck after their finances took a hit following the Bernie Madoff scandal.'

'NPR looks at how the Mets found success in youth and luck after their finances took a hit following the Bernie Madoff scandal.'

Published on October 30, 2015 16:41

October 29, 2015

#Culture360: #AssaultAtSpringValley + 'Being Mary Jane'

News outlets across the country played a cell phone video this week of a white sheriff’s deputy in South Carolina violently arresting a black female student. The officer was fired, but public dialogue continues about the video and the alarming questions it raises about how school authorities discipline students. In pop culture, television programs like Being Mary Jane are challenging media's portrayal of black women.

News outlets across the country played a cell phone video this week of a white sheriff’s deputy in South Carolina violently arresting a black female student. The officer was fired, but public dialogue continues about the video and the alarming questions it raises about how school authorities discipline students. In pop culture, television programs like Being Mary Jane are challenging media's portrayal of black women. In this episode of #Culture360 WUNC host Frank Stasio talks with Natalie Bullock Brown , professor of film and multimedia at St. Augustine University and Mark Anthony Neal , professor of African & African American Studies about race and discipline in the classroom, Being Mary Jane, and Kendrick Lamar's recent performance at the Kennedy Center.

Published on October 29, 2015 15:06

‘Bad Men Doing Bad Things’: K-12 and The Misdirection Myth of the True Roots of Racism

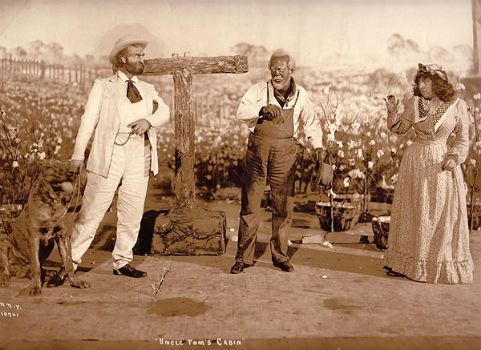

Simon Legree‘Bad Men Doing Bad Things’: K-12 and The Misdirection Myth of the True Roots of Racism by Keffrelyn D. Brown | The Op-Ed Project | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Simon Legree‘Bad Men Doing Bad Things’: K-12 and The Misdirection Myth of the True Roots of Racism by Keffrelyn D. Brown | The Op-Ed Project | NewBlackMan (in Exile)From George Zimmerman, Donald Sterling and Dylann Roof to the Ku Klux Klan, Eugene “Bull” Connor and Strom Thurmond, when it comes to teaching about American-style racism, the narrative gets boiled down to bad men doing bad things.

In a time when the country can’t parse the meaning of #blacklivesmatter vs #allivesmatter, we continually engage in an incomplete dialogue around race and racism. This miseducation starts at school, where we need to take a different approach if we hope to come to common ground in the larger conversation around these issues.

For many well-meaning people concerned about race the aforementioned names and words conjure images of the consummate racist: an individual or group of people whose actions are motivated by overt racial bias and prejudice. Over time the images of “bad men who did bad things,” become emblematic of American racism, blinding us to the insidious ways racism impacts us every day. Not so incidentally, they emblems of badness are generally always positioned as bad men. This is the prototypical way race is understood in U.S. society and taught in official school curriculum.

Yet when racism is viewed only as the individual actions of a person or group toward others, it is disconnected from the histories and practices that have helped to maintain its power. This individual view of racism slips into the idiosyncratic; racism becomes simply the interpersonal relations between “bad” and good people.

In fact, racism is a historic feature of our country, existing since its founding and ratification by the U.S. Constitution. Some legal scholars such as the late Derrick Bell even argue persuasively that it holds a foundational and permanent place in U.S. social relations. One cannot deny the legacy racism has played in our country’s major institutions. Politics, law enforcement, media, education, health care and housing are all mired in a system historically characterized by racialized inequities and oppression.

Yet when researchers look at how racism is treated in the official school curriculum, specifically in social studies, an area ripe for this exploration, one finds a different perspective. In a study I conducted with Anthony Brown on how Texas state adopted U.S. history textbooks across grades 5, 8 and 11 addressed racial violence targeted to African-Americans, we found racism positioned as individual behavior. Racism, even in the context of state-sanctioned, extra-legal violence rested on the individual predilection of individuals alternately depicted as different from normal, presumably non-racist people who had no culpability in our system of white supremacy.

But is this the only knowledge that more than 50 million children attending U.S. public schools today learn about race in school? No. Racism is also taught in an indirect, more pervasive way through what is called the “hidden curriculum.” This is accessed through the organization of schools and students, in the knowledge offered or left out of official school curricula, and through the curriculum and teaching decisions teachers still make, in spite of increased standardization of their practices. The challenge of indirect forms of racism found in schools is students absorb them without ever having to unpack their significance and power.

As a black female, I experienced this in my K-12 schooling. I encountered African-Americans in the curriculum only in the context of learning about slavery and in two texts assigned in my Advanced Placement English classes. This gap continues in my own son’s education. Every year we push his educators to provide a more racially inclusive curriculum through the inclusion of books and other material that reflect a fuller representation of blackness, black people and the place of race in our society.

Certainly, schools cannot end racism. Racism reflects a set of deeply entrenched histories and social practices that cannot be upended through the implementation of a magical curriculum. But acknowledging this does not diminish the need to disrupt how racism is taught — officially and informally — in schools.

K-12 schools need to intentionally teach students about race and the fundamental role racism plays in schools and society. But this would require schools take a radically different approach in acknowledging what I call sociocultural knowledge, the social, cultural, economic, political and historical knowledge that informs society. It impacts every aspect of teaching from curriculum and approaches to teaching to daily decisions teachers make about them both. It also impacts classroom organization and how teachers view their role and responsibility as teachers, their students and the families and communities from which students come. Too often educators and researchers dismiss sociocultural knowledge as only the context surrounding school, rather than knowledge constitutive to the fundamental work of school.

If we truly want to transform the work of schools, society and future of this country, we need to ask ourselves what knowledge matters and what knowledge is forsaken. In addition to the traditionally exalted disciplinary knowledge of science, mathematics, literacy and social studies, we need recognize sociocultural knowledge, in this case race, as venerated and valid curriculum.

All teachers need this knowledge, but at a time when 80 percent of teachers are white and 50 percent of students are of color, this is vitally important. Those preparing to become teachers and those currently in classrooms need targeted opportunities to acquire a stronger sociocultural knowledge of race and racism. This is just as important as content area knowledge teachers are expected to know and teach.

+++

Dr. Keffrelyn Brown, a Public Voices Fellow, is an associate professor in curriculum and instruction at the University of Texas at Austin. Follow her on Twitter: @DrKeffrelynB

Published on October 29, 2015 13:53

Upcoming Episodes of Left of Black (Fall 2015): Black Studies for the Digital Soul

Upcoming Episodes of Left of Black (Fall 2015)Black Studies for the Digital Soul

Upcoming Episodes of Left of Black (Fall 2015)Black Studies for the Digital Soul• October 30th – Left of Black on the Root with Jasmine Nicole CobbFull Episode S6:E8 Available Available on November 2nd

Jasmine Cobb is the author of Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (NYU Press)

• November 6th – Left of Black on the Root with Candice JenkinsFull Episode S6:E9 Available on November 9th

Candice Jenkins is the author of Private Lives, Proper Relations: Regulating Black Intimacy (University of Minnesota Press)

• Nov. 13th – Left of Black on the Root with Jessica Marie Johnson (on Location at Lehigh U)Full Episode S6:E10 Available on November 16th

Jessica Marie Johnson is the founder and managing editor of African Diaspora, Ph.D + Diaspora Hypertext, the Blog.

• Nov. 20th – Left of Black on the Root -- NewBlackMan Ancestry Reveal with African Ancestry Co-Founder Dr. Rick Kittles + Professor Charmine Royal + Professor Karla FC Holloway

Full Episode S6:E11 Available on November 23rd

• Nov. 27th – Left of Black on the Root with Tsitsi JajiFull Episode S6:E12 Available on November 30th

Tsitsi Jaji is the author of Africa in Stereo: Modernism, Music, and Pan-African Solidarity (Oxford University Press)

• Dec. 4th – Left of Black on the Root with Sherrie M. RandolphFull Episode S6:E13 Available on December 7th

Sherrie M. Randolph is author of Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical (UNC Press)

***

Upcoming in the Spring Season (2016):

Bettina Love

Adam Mansbach

Ed Pavilc

Alexis De Veaux

#BlackMovementMatters with Tommy DeFrantz + Rennie Harris PureMovement

And... Left of Black Africa

Published on October 29, 2015 07:05

October 28, 2015

WatchLOUD: Paris On His New Album 'Pistol Politics' & #BlackLivesMatter

'This year has Paris released Pistol Politics, a double album featuring kindred spirits like dead prez, Chuck D and Kam on his own Guerilla Funk label. In a climate of heightened awareness surrounding racial injustice in America, Paris feels this is a time for a musical reality check.' -- +WatchLOUD

'This year has Paris released Pistol Politics, a double album featuring kindred spirits like dead prez, Chuck D and Kam on his own Guerilla Funk label. In a climate of heightened awareness surrounding racial injustice in America, Paris feels this is a time for a musical reality check.' -- +WatchLOUD

Published on October 28, 2015 20:59

Left of Black S6:E7: The Black Arts Movement + #BlackLivesMatters + 21st Century Black Aesthetics.

Left of Black S6:E7: The Black Arts Movement + #BLM + 21st Century Black Aesthetics.

Left of Black S6:E7: The Black Arts Movement + #BLM + 21st Century Black Aesthetics.Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined on location in Durham, NC by Margo Natalie Crawford Associate Professor of English at Cornell University.

Crawford discusses the role of aesthetics in the Black Arts Movement and #BlackLivesMatter, and the ways that BLM actively engages the symbolism and gestures of the Black Liberation Movement of the 1960s. Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on October 28, 2015 20:37

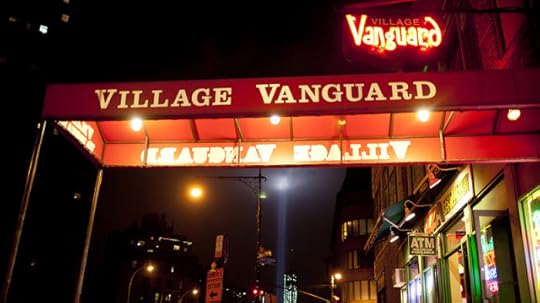

Jazz Night in America: Why Everyone Wants To Record 'Live At The Village Vanguard'

'On

Jazz Night in America

Bassist Christian McBride says that making his own album at the storied jazz club was like becoming part of a family. He knew: "We'd better bring it harder than we've brought it anywhere else before." -- +NPR Music

'On

Jazz Night in America

Bassist Christian McBride says that making his own album at the storied jazz club was like becoming part of a family. He knew: "We'd better bring it harder than we've brought it anywhere else before." -- +NPR Music

Published on October 28, 2015 19:56

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.