Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 688

October 19, 2015

Alvin Ailey: 'Exodus'--Choreography by Rennie Harris

'Acclaimed hip-hop choreographer Rennie (Lorenzo) Harris creates a highly-anticipated world premiere that explores the idea of “exodus” – from one’s ignorance and conformity – as a necessary step toward enlightenment. Set to gospel and house music along with poetic narration, the work underscores the crucial role of action and movement in effecting change. Exemplifying his view of hip hop as a “celebration of life,” Exodus marks Harris’ latest invitation to return to spiritual basics and affirm who we are. Mr. Harris’ previous contributions to the Ailey repertory include Home (2011) and Love Stories (2004), the latter of which was a collaboration with Judith Jamison and Robert Battle.'

'Acclaimed hip-hop choreographer Rennie (Lorenzo) Harris creates a highly-anticipated world premiere that explores the idea of “exodus” – from one’s ignorance and conformity – as a necessary step toward enlightenment. Set to gospel and house music along with poetic narration, the work underscores the crucial role of action and movement in effecting change. Exemplifying his view of hip hop as a “celebration of life,” Exodus marks Harris’ latest invitation to return to spiritual basics and affirm who we are. Mr. Harris’ previous contributions to the Ailey repertory include Home (2011) and Love Stories (2004), the latter of which was a collaboration with Judith Jamison and Robert Battle.'

Published on October 19, 2015 09:49

Nowness: Skating in Cuba--Mapping Havana's Four-Wheel Revolution

'While Cuban skaters struggle to get their hands on new equipment and dedicated ramps, this hasn't deterred one skateboarding community thriving in the suburbs of Havana. At the forefront of this is regular rider Yojani Perez Rivera, who shares the sport's role in a changing social and political landscape, in this film directed by Ivan Olita.' -- via +NOWNESS

'While Cuban skaters struggle to get their hands on new equipment and dedicated ramps, this hasn't deterred one skateboarding community thriving in the suburbs of Havana. At the forefront of this is regular rider Yojani Perez Rivera, who shares the sport's role in a changing social and political landscape, in this film directed by Ivan Olita.' -- via +NOWNESS

Published on October 19, 2015 03:04

Where The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Met Harlem's House and Ballroom Scene

YOU BETTA WERK celebrates the convergence of two seminal liberation movements that emerged out of Harlem; The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the House and Ballroom Scene. These distinct liberation movements can be understood as aftershocks of the Great Migration, where massive population shifts of black Americans from the rural south to urban centers transformed political and creative cultures and provoked new ways of organizing. Guests include Davarian Baldwin + Alicia Garza + Uri McMillan + Kevin Omni Burrus + niv Acosta.

YOU BETTA WERK celebrates the convergence of two seminal liberation movements that emerged out of Harlem; The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the House and Ballroom Scene. These distinct liberation movements can be understood as aftershocks of the Great Migration, where massive population shifts of black Americans from the rural south to urban centers transformed political and creative cultures and provoked new ways of organizing. Guests include Davarian Baldwin + Alicia Garza + Uri McMillan + Kevin Omni Burrus + niv Acosta.YOU BETTA WERK is organized by historian Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, author of the critically acclaimed Harlem Is Nowhere: A Journey to the Mecca of Black America and the illustrated children’s story Jake Makes a World: Jacob Lawrence, A Young Artist in Harlem.

Published on October 19, 2015 02:58

#BlackMovementMatters: Dance, Hip-Hop + Social Justice -- Wednesday October 21st

Wednesdays at the Center at the John Hope Franklin Center

Wednesdays at the Center at the John Hope Franklin Center Duke University Wednesday, October 21 | 12 pm Free & Open to the Public

#BLACKMOVEMENTMATTERS: DANCE, HIP-HOP AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

Rennie Harris, founder and artistic director of hip-hop dance company Rennie Harris Puremovement, chats with Thomas DeFrantz, chair of the Department of African and African American Studies at Duke and a professor of dance, in a conversation exploring Harris' career and work, and the global influence of hip-hop dance and culture, moderated by Duke professor Mark Anthony Neal. Rennie Harris Puremovement performs on Friday, October 23 and Saturday, October 24 at Duke's Reynolds Theater.

###

Rennie Harris is one of the great veterans of hip-hop dance, having broken down barriers between the vocabulary of the street and the vocabulary of the concert hall for nearly forty years. At the age of twelve he formed his first crew, and by the age of twenty-five he had shared the stage with many of hip-hop’s founders, including Run DMC, Sugarhill Gang, Salt ’n’ Pepa, and Kurtis Blow. He comes to Reynolds Theater with his company Rennie Harris Puremovement, repeat Bessie Award-winners whom The New York Times call “phenomenal” and “seemingly without a semblance of gravity.”

Thomas F. DeFrantz is Chair of African and African American Studies and Professor of Dance, and Theater Studies at Duke University. He is past-president of the Society of Dance History Scholars, an international organization that advances the field of dance studies through research, publication, performance, and outreach to audiences across the arts, humanities, and social sciences. He is also the director of SLIPPAGE: Performance, Culture, Technology, a research group that explores emerging technology in live performance applications. He convenes the working group Black Performance Theory and the Collegium for African Diaspora Dance. His books include the edited volume Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance (2002) and Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture (2004) and Black Performance Theory co-edited with Anita Gonzalez.

###

Wednesday, October 21, 12 - 1 PM

John Hope Franklin Center, 2204 Erwin Road, Rm. 240, Durham (Directions)

Free & open to the public; a light lunch will be served and parking is available in nearby parking decks.

Presented in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center, the Department of African and African American Studies, and the Dance Program at Duke University.

Made possible, in part, by support from the N.C. Arts Council, a division of the Department of Cultural Resources; a Visiting Artist Grant from the Council for the Arts, Office of the Provost, Duke University; and support from the Dance Program at Duke University.

Published on October 19, 2015 02:39

October 18, 2015

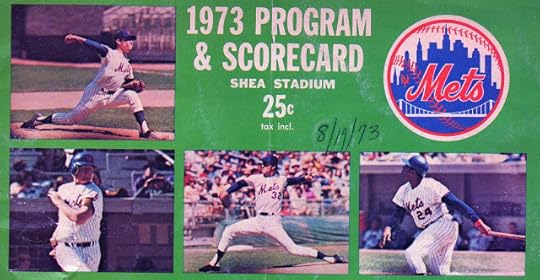

Baseball + The New York Mets + the Love Language Between Father and Son by Mark Anthony Neal

Baseball + The New York Mets + the Love Language Between Father and Sonby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Baseball + The New York Mets + the Love Language Between Father and Sonby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Koosman. Matlack. And of course, Seaver. Those were the names most mentioned, when dad, and I sat in front of the television, mostly on Sunday afternoons, with the voices of Nelson, Murphy, and of course Kiner recalling history and the details of a game, that many who came the generation after I did, would have little use for.

For my dad, baseball was everything--as everything as those Gospel quartets, and those Hammond B-3 players, and the small bottle of Johnnie Walker Red that was never too far away, but never present enough for anyone to think he had a problem with it.

What became the ritual for us--and perhaps the only ritual my dad had with his young son, and only child--began in 1972 framed by two deaths and a trade. The deaths of New York Mets manager Gil Hodges on the eve of the 1972 season, and Jackie Robinson that fall, along with the trade of Willie Mays to the Mets, were the context for my dad to provide broader historical context: Gil Hodges’ days as a Brooklyn Dodger, Jackie Robinson’s trampling of the Baseball’s color-line, only 18 years before my birth, and the Man-Child genius who roamed centerfield for New York’s Giants right where Harlem met the Bronx.

At its essence Baseball is a game obsessed with history and Big Data (statistics), so there’s probably some connection to the history I trolled as a young boy in my Encyclopedia Britannica collections (the analog Google) and my current vocation. Baseball is also a game of strategy, and if my father had a love language for his son, it was articulated by bunts, hit-and-run plays, double-steals, sliders, and fastballs on the corner.

The 1973 season--Mays’ last--was the occasion for my dad to experience a Championship season with his son, who was too young to remember the Miracle Mets of 1969, though I had by then read every historical account of that magical season to claim it as my own.

There was no reason for that Mets team in 1973--who had the worst record of any team to appear in a World Series--to imagine that they could win a championship, yet they took out the “Big Red Machine” in five games, the series punctuated by Pete Rose’s takeout of shortstop Bud Harrelson (not unlike what Chase Utley did to Ruben Tejada recently). There was even less expectation that the Mets could realistically challenge the Oakland A’s, arguably the 1970s most successful team, three-peating during the decade--a feat unmatched in the sport since.

My dad and I watched every one of those 1973 World Series games together--it was the first series to feature night games, though I remember the Saturday and Sunday afternoon games the most. Game 2, an extra-inning affair, marked Willie Mays’ last hit as a professional, yet I remember most the indelible image of the aging icon, on his knees pleading with umpire Augie Donatelli over a missed call at home plate. I remember thinking that Mays looked old, though he was only four years older than my dad, and seven-years younger than I am now. My dad and I never talked about that image or that of Mays falling in the outfield trying to make a play he once made with ease--his other love language was interested silence--though it was my introduction to the fragility of masculinity.

The Mets would be denied that Autumn of 1973, and would go through some significant down years before they reemerged as a force in the 1980s on the strength of two young Black men named Strawberry and Gooden who were of my generation of Black boys. When the Mets won the World Series in 1986, I was a senior in college, and the first call I made was to my dad. I made the same such call to my dad in the Fall of 2000, when the Mets and Yankees met for the first subway series in since the Yankees beat the Dodgers in 1956 in a series that featured Don Larsen’s historic perfect game. I watch much of that 2000 series with a sleeping two-year-old daugher in my lap.

My father would not live long enough to know the names Harvey, Syndergaard, deGrom Cespedes, and Granderson. This year’s run, which may not end up with an appearance in the World Series, is as improbable as that run in 1973. My dad would have loved this team, especially Granderson, because he just loved the idea of Black boys who loved the game. I’m wearing Grandy’s #3 jersey now, as I will be, watching the Met game tonight...with my dad.

Published on October 18, 2015 12:50

Visions + Music: Mizan--"7 Billion"

Published on October 18, 2015 10:31

Amiri Baraka: The Black Nationalist Ethic and Black Internationalism

Panel: The Black Nationalist Ethic and Black Internationalism with Komozi Woodard + Michael Simanga + Alex Carter + Moderator Kenneth Janken.

Panel: The Black Nationalist Ethic and Black Internationalism with Komozi Woodard + Michael Simanga + Alex Carter + Moderator Kenneth Janken. from Amiri Baraka: Meetings and Remarkable Journeys @ the Sonja Haynes Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (September 17-18, 2015). Amiri Baraka: Meetings and Remarkable Journeys, Panel 2, 17 September 2015 from Sonja Haynes Stone Center on Vimeo.

Published on October 18, 2015 10:15

Marcus Garvey + #BlackLivesMatters + The Myth of Leaderless Black Movements

In this episode of

LeftofBlack on TheRoot,

Historian Natanya Duncan discusses Marcus Garvey, #BlackLivesMatter and the Myth of Leaderless Black Movements. Professor Duncan is Assistant Professor of History and Africana at Lehigh University; She is completing a book on The Women of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

In this episode of

LeftofBlack on TheRoot,

Historian Natanya Duncan discusses Marcus Garvey, #BlackLivesMatter and the Myth of Leaderless Black Movements. Professor Duncan is Assistant Professor of History and Africana at Lehigh University; She is completing a book on The Women of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

Published on October 18, 2015 06:35

October 16, 2015

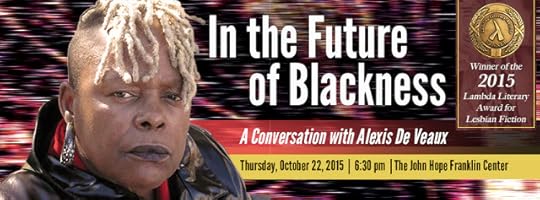

In the Future of Blackness: A Conversation with Alexis De Veaux @ Duke University 10/22

In the Future of Blackness: A Conversation with Alexis De Veaux

In the Future of Blackness: A Conversation with Alexis De VeauxThursday October 22, 2015 @ 6:30pmDuke UniversityJohn Hope Franklin Center for International and Interdisciplinary Studies 2204 Erwin Road, Durham, NC 27708

Alexis De Veaux is the 2015 Lambda Award Winner for Lesbian for fiction for her novel Yabo. A former contributing editor at Essence Magazine and Chair of Women’s Studies at the University of Buffalo, De Veaux is also the author of an award winning biography of Audre Lorde, Warrior Poet. De Veaux has also published several children’s books including The Enchanted Hair Tale.

Sponsored by the Center for Arts, Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) in collaboartion with the Duke Council on Race and Ethnicity (DCORE) + the Duke Program in Women’s Studies + the Department of African and African-American Studies + the John Hope Franklin Center for International and Interdisciplinary Studies.

Published on October 16, 2015 13:20

October 15, 2015

Beats + Vision from "Every Ghetto"--Talib Kweli featuring Rapsody

Beats + Vision from "Every Ghetto"--Talib Kweli featuring Rapsody from 9th Wonder and Talib Kweli Present Indie 500. Video directed by Cam Be; Production by Hi-Tek.

Beats + Vision from "Every Ghetto"--Talib Kweli featuring Rapsody from 9th Wonder and Talib Kweli Present Indie 500. Video directed by Cam Be; Production by Hi-Tek.

Published on October 15, 2015 13:39

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.