Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 640

February 25, 2016

A Black Theatrical Renaissance in the #BlackLivesMatter Era by Lisa B. Thompson

A Black Theatrical Renaissance in the #BlackLivesMatter Eraby Lisa B. Thompson | @PlayProf | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

A Black Theatrical Renaissance in the #BlackLivesMatter Eraby Lisa B. Thompson | @PlayProf | NewBlackMan (in Exile)While the nation has been captivated by the #OscarsSoWhite campaign there’s been a quiet revolution happening on New York’s stages. Indeed American theatre has never been so diverse. Everyone knows that the hottest ticket in town is a front row center seat at Lin Manuel’s Hamilton, winner of a Grammy for Best Musical Theater Album. The Great White Way has never had more color. Not since 2011 when Lydia Diamond’s Stick Fly, Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and the Suzan-Lori Parks revised book for Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess all appeared on Broadway during the same season has black theatre been so visible.

Are we are living through a black theatrical renaissance? Currently there are a number of shows written by and/or starring African Americans receiving commercial success and critical acclaim. It’s as if the theatre of rebellion and protest against police brutality raging throughout the country has captured America’s imagination and opened up opportunities for more voices by black theatrical artists.

Remarkable black theatre is available for the price of the ticket and while that’s no small matter its worth it to see such rich portraits of black life. Currently Academy Award winner Forest Whitaker is making his Broadway debut in Eugene O’Neil’s Hughie. Another remarkable thing about this revival is that Tony winning African American film & theatre producer Ron Simons, CEO of Simonssays Entertainment, is one of the producing team. Whitaker is not the only famous black performer making a Broadway debut this season.

Remarkable black theatre is available for the price of the ticket and while that’s no small matter its worth it to see such rich portraits of black life. Currently Academy Award winner Forest Whitaker is making his Broadway debut in Eugene O’Neil’s Hughie. Another remarkable thing about this revival is that Tony winning African American film & theatre producer Ron Simons, CEO of Simonssays Entertainment, is one of the producing team. Whitaker is not the only famous black performer making a Broadway debut this season. The revival of The Color Purple marks the Broadway debuts of Oscar and Grammy winner, Jennifer Hudson, Cynthia Erivo and the Orange is the New Black star, Danielle Brooks. Danai Gurira’s Eclipsed directed Liesl Tommy starring Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o just began previews this week making history as the first Broadway show with a black woman writer, director and cast.

Other riveting plays this season include Lydia Diamond’s muscular exploration of race Smart People directed by Tony winner Kenny Leon, and Dot by award winning actor/director/playwright Colman Domingo directed by Tony winner Susan Stroman, an heartfelt examination of the impact of dementia on African American families.

This moment of black theatrical riches is not limited to only plays, but also includes musicals such as City Opera’s recent limited engagement of A Cabin in the Sky featuring Tony nominee Norm Lewis Tony winners Chuck Cooper and LaChanze and the Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake juggernaut Shuffle Along directed by Tony winner George Wolfe begins previews next month. Shuffle Along stars six time Tony award winner Audra McDonald, choreographed by Savion Glover and featuring a slew of other award winning performers: Tony winners Brian Stokes Mitchell and Billy Porter, as well as Tony nominees Brandon Victor Dixon and Joshua Henry.

At this moment black theatre artists are not only dominating the commercial and artistic arena, they are having critical success as well. Pulitzer winner Lynn Nottage just won the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, “the oldest and largest prize awarded to women playwrights” for her new play Sweat.

Does this current renaissance suggest that we will see a permanent shift in American theatre? We can only hope that this kind of momentum will insure that Artistic Directors everywhere green light projects when scripts by black playwrights arrive on their desks. Black theatre continues to be as important today as it was when in 1926 W. E. B. Du Bois in the Crisis called for theatre “about us, by us, for us, near us” and in 1965 when Amiri Baraka demanded a revolutionary black theatre that “moves to reshape the world.”

It does give me pause that most of this success is happening in predominantly outside the black theatres. In 1996 August Wilson decried the lack of funding and support for black theatres and twenty years after Wilson’s speech things remain precarious. In this moment all the attention should not be focused on Broadway. Theaters such as Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, Kenny Leon’s True Colors Theatre in Atlanta, Crossroads Theatre Company in New Jersey, the Classical Theatre of Harlem as well as Woodie King’s venerable New Federal Theatre are also producing new work and reviving black theatre classics.

If the work of the black theatrical renaissance appears at these theatres, so that new black voices who have not won Tony awards or Pulitzer prizes grace America’s stages then there is hope for the kind of black revolutionary theatre Du Bois, Baraka and Wilson called for during in the last century. I’ll be front row center.

+++

Lisa B. Thompson is a playwright and associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at UT Austin and former OpEd Project Public Voices fellow. She is author of Single Black Female and Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African American Middle Class. She is currently writing a book about representations of history and contemporary African American theatre. Follow her on Twitter @playprof.

Published on February 25, 2016 20:41

February 24, 2016

Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie: "How to be a Woman According to Prime Time" (Poem)

Published on February 24, 2016 20:08

'Freedom' Before 'Formation': In the Archive of Black Women's Art

These two all-Black-Women artist clips, based on a composition by Joi Gilliam and inspired by the film Panther (dir. Mario Van Peebles, 1995) is a reminder of the archive that Beyonce and her collaborators drew from for "Formation." Wonder what Rudolph Guliani had to say twenty-one years ago?

These two all-Black-Women artist clips, based on a composition by Joi Gilliam and inspired by the film Panther (dir. Mario Van Peebles, 1995) is a reminder of the archive that Beyonce and her collaborators drew from for "Formation." Wonder what Rudolph Guliani had to say twenty-one years ago?

Published on February 24, 2016 19:36

What If the Greensboro Four Had Twitter? Social Justice from the Analog to the Digital Era

DCRI Diversity & Inclusion Lecture

DCRI Diversity & Inclusion Lecture North Pavilion Lower Level Lecture Hall

Wednesday, February 24

1:00 – 2:00 PM Mark Anthony Neal, PhD Professor, African & African American Studies Founding Director, Center for Arts, Digital Culture, and Entrepreneurship “What if the Greensboro Four had Twitter? Social Justice from the Analog to the Digital Era”

The DCRI will honor that tradition as part of its Diversity Lecture Series.

Published on February 24, 2016 04:38

February 23, 2016

‘Race’ Mythologizes a Coach & Hitler’s Olympics; Marginalizes Jesse Owens’s Life & American Racism by Stephane Dunn

‘Race’ Mythologizes a Coach & Hitler’s Olympics; Marginalizes Jesse Owens’s Life & American Racismby Stephane Dunn | @DrStephaneDunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

‘Race’ Mythologizes a Coach & Hitler’s Olympics; Marginalizes Jesse Owens’s Life & American Racismby Stephane Dunn | @DrStephaneDunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)It’s been a long time coming. Jesse Owens’s life has been a no brainer for major motion picture treatment. His story has been largely distilled into a singular famous chapter, the 1936 Berlin Olympics when he famously frustrated Hitler’s intended representation of Aryan superiority by winning four gold medals and besting the German World Champion athlete, Luz Long.

However, the life of Owens is a powerful narrative about much more than Olympic glory earned when Hitler’s terrible project of ethnic cleansing had begun in earnest. It’s about American racism too – a chapter that requires the camera’s gaze on life before the Olympics, before Ohio State even, and most certainly post the Olympics.

The new film Race, directed by Stephen Hopkins and starring the talented up and coming Stephan James of John Lewis Selma fame, spends much of the screen time on a super fictionalized account of Jesse’s track time at Ohio State and the rest primarily on the actual Olympic games. The visual rendering of James as Owens on the track field is impressive as James is able to imbibe Owen’s convincingly enough especially in his running form.

Unfortunately, Race recycles some by now all too familiar tendencies of Hollywood films dramatizing the story of Black heroic figures in extraordinary historical moments. Hopkins has said that the script for the film explored more of Owen’s life after the Olympics but he decided that the story, the important story, was the Olympic moment, the most familiar part of Jesse Owens’s life.

The Hitler part of the story is well known and not altogether shocking since we know how Hitler felt about Jewish people and Black people as well. The neglect of Owen’s life after the Olympics, when he came home to years of economic struggle amid the same Jim Crow society he’d confronted before Germany, is costly.

In lieu of intimate or deeper attention to his family history and relationships– mother, father (Henry and Emma Owens), siblings, or even to the extraordinary instance of his being an unmarried teenage father in the early 1930s, the film attends to establishing a larger-than-life coach played by Jason Sudeikis–the archetypical noble white character who acts as a foil to American racism; the relationship between he and Owens becomes the single most important one depicted in this ‘biopic’ of Owens’s life while the latter’s father and mother are virtually mute and back grounded throughout. The film busies itself making sure Nazi racism gets a star turn and that American racism gets a passing nod.

President Franklin Roosevelt did not congratulate Owens with the normal letter or invite to the White House. The fact that the American government at the time of Owens’s Olympic glory denied him is given scant attention save for an ending sentence tag rolled across the screen with a number of others. Owens' horse racing for money and other struggles are absent too.

Owen’s daughters approved of the script and the resulting film. It’s understandable that they did given the extremely overdue motion picture treatment of their father’s story. But this doesn’t mean that Jesse Owens, his family, and moviegoers, who don’t know him at all or know him only in relation to that infamous Olympics, didn’t deserve more Jessie Owens and less Coach Snyder.

+++

Writer and professor Stephane Dunn, PhD, is the director of the Cinema, Television, & Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College. She teaches film, creative writing, and literature. She is the author of the 2008 book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films (U of Illinois Press). Follow her on Twitter: @DrStephaneDunn

Published on February 23, 2016 16:47

February 22, 2016

#WUNCBackChannel: Kendrick Lamar's Chain Gang + Beyonce's Formation + Maurice White's Elements

On this episode of #WUNCBackChannel host Frank Stasio talks with popular culture experts Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and multimedia studies at St. Augustine's University, and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American studies at Duke University, about the way musicians' race-related messages are interpreted by different audiences.

On this episode of #WUNCBackChannel host Frank Stasio talks with popular culture experts Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and multimedia studies at St. Augustine's University, and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American studies at Duke University, about the way musicians' race-related messages are interpreted by different audiences.

Published on February 22, 2016 20:28

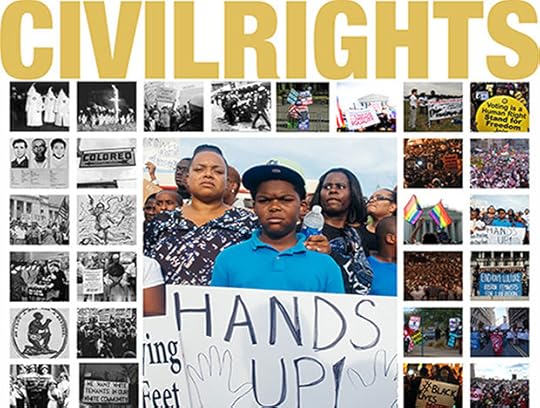

The Present & Future of Civil Rights Movements

'Duke Law's Center on Law, Race and Politics hosted a conference on November 20-21, 2015, bringing together scholars and experts to discuss civil rights. In 2014, the nation marked the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Freedom Summer. In 2015, we recognized the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Moving into the 21st century, America finds itself at the beginning of a new era defined by its own set of civil rights struggles.' -- +Duke University School of Law

'Duke Law's Center on Law, Race and Politics hosted a conference on November 20-21, 2015, bringing together scholars and experts to discuss civil rights. In 2014, the nation marked the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Freedom Summer. In 2015, we recognized the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Moving into the 21st century, America finds itself at the beginning of a new era defined by its own set of civil rights struggles.' -- +Duke University School of Law

Published on February 22, 2016 16:53

BK Live: Empowering Black Women in Beauty & Media

'Two media makers, Asha Boston and Tia Williams, discuss their view on how African American women are portrayed in the media. Boston organizes local empowerment workshops and conversations with teen girls of color; she's also President and CEO of her own production company and has worked at AMC and BET networks. Having spent 15 years as a beauty editor at media giants like Elle, Glamour, and Essence.com, Tia Williams is now an author of several books and is the copy director at Bumble and Bumble, a global hair care brand owned by Estee Lauder Companies.' -- +BRIC TV

'Two media makers, Asha Boston and Tia Williams, discuss their view on how African American women are portrayed in the media. Boston organizes local empowerment workshops and conversations with teen girls of color; she's also President and CEO of her own production company and has worked at AMC and BET networks. Having spent 15 years as a beauty editor at media giants like Elle, Glamour, and Essence.com, Tia Williams is now an author of several books and is the copy director at Bumble and Bumble, a global hair care brand owned by Estee Lauder Companies.' -- +BRIC TV

Published on February 22, 2016 16:44

Riled by Glass Ceilings: Perseverance, Skill Credited for Historic Growth in Black Female Entrepreneurship

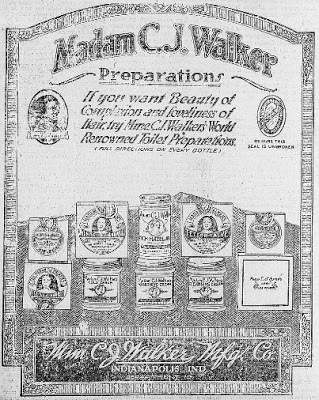

ad for products from Madam C.J. WalkerRiled by Glass Ceilings: Perseverance, Skill Credited for Historic Growth in Black Female Entrepreneurshipby Edna Kane-Williams | @Ekanewilliams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

ad for products from Madam C.J. WalkerRiled by Glass Ceilings: Perseverance, Skill Credited for Historic Growth in Black Female Entrepreneurshipby Edna Kane-Williams | @Ekanewilliams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Given the pioneering success of Madam C. J. Walker, America's first self-made black woman millionaire, people wanted to know how she got started in business ownership only decades after the end of slavery in America. Her answer was short and simple: "I got my start by giving myself a start."

As for her astronomical success as owner of an Indianapolis-based hair and skin care factory, Walker had yet another pithy saying: "Perseverance is my motto."

More than a century later, these morsels of wisdom still work - at least according to economic experts and advocates who have observed the historic rise of black women entrepreneurs over the past 18 years. According to an American Express Open study released in 2015, there's been a 322 percent growth in black female-owned businesses since 1997, making black women the fastest growing entrepreneurial group in America.

The same self-start, perseverance and faith employed by Walker is still motivating Black women in 2016, says Julianne Malveaux, an economist and former president of Bennett College for Women.

"African-American women have earned degrees, have moved up the ladder, and have found corporate America sometimes wanting and have found the mainstream difficult," Malveaux says. "Therefore, the 322 percent increase is a function of people being very skilled and talented and not finding space for themselves in the traditional pipelines. And so they are going into creating their own."

Margot Dorfman, CEO of the U.S. Women's Chamber of Commerce, agrees. "Women of color, when you look at the statistics, are impacted more significantly by all of the negative factors that women face. It's not surprising that they have chosen to invest in themselves," Dorfman told Fortune magazine.

Yet, Malveaux points out, it is crucial to note that despite the growth of black women entrepreneurs due to their talent and tenacity, they are still a huge minority when compared to white women.

BlackEnterprise.com reports that women in general now own 30 percent of all businesses in the United States, accounting for some 9.4 million firms. African-American women control 14 percent of these companies, or an estimated 1.3 million businesses. In contrast, white women own 6.1 million, the lion's share of the women-owned firms, according to the National Women's Business Council.

Generally, black businesses - owned by men and women - still lag grossly behind those owned by whites, says Malveaux. "The issue is that African Americans are less likely to have access to capital and African-American women are even less likely than that. In terms of access to capital, no African American has a level playing field."

The Wall Street Journal reported in 2014 that black-owned businesses, which once received 8.2 percent of all loans from the U.S. Small Business Administration, had dropped to only 2.3 percent.

From a black man's perspective, it has been inspiring to observe the growth of entrepreneurship among determined black women, says Howard R. Jean, co-founder of the Black Male Entrepreneurship Institute. He concludes the growth is spurred, in part, by black women increasingly realizing their worth.

"It comes to a point when women have stopped begging for a seat in the boardroom and began creating their own," Jean says. "Realizing their value on the open market and capitalizing on the certification pools that increase their opportunities for success in business, women are now in a position of influence in the business community."

+++

Edna Kane-Williams is senior vice president for multicultural leadership at AARP.

Published on February 22, 2016 16:19

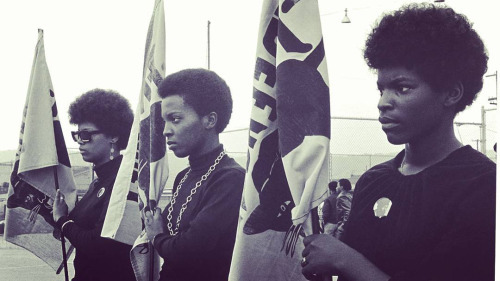

How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Person--On 'Vanguard of the Revolution'

“ . . . ; all you had to be was a human being.”: How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Personby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“ . . . ; all you had to be was a human being.”: How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Personby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)I could not help hearing my mother’s voice throughout the airing of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. She kept uttering: 1) “Growing up, we had so little yet did so much; now we have so much yet do so little”, and 2) “Just because we wear the same uniform does not mean we are united.” Perhaps the former quip is more apropos to then as the latter is to now, or maybe not, which is something I would debate, with anyone. Nonetheless, while watching Tuesday night, I fell into that ever-lingering affect that can be generative or detrimental: I became nostalgic.

We live in a society where some animals are treated better than others. (Look where the others live!) Furthermore, some people presume some animals to be more human than humans, hence those animals’ more humane treatment and societal reception. Yet this project forces us to wrestle with being summoned as character witnesses in the case of that all-too-familiar literary trope of the human versus nature. It appears, however, that the verdict is not guilty—the agential calculation to pose as, not “be”, an animal, a black panther to be exact, exemplifies the full spectrum of human expression and its condition as adjudicated by a jury of one’s peers.

The animality of the panther is a ruse for the animation of the person.

Some people, unfortunately, still do not get that.

Where the others live, there are proverbs. Proverbs and parables. Parables about elephants. A parable about elephants analogizes the party of black panthers. A party of panthers is akin to a pride of lions. These are collective nouns that capture in miniature a collectivity, its spirit. Another proverb from where the others live: the spirit will not descend without song.

Listening to the collective sing about, call forth, an other’s freedom—“FREE HUEY!”—takes on religious interpretation such that these Panthers—young and old, educated and sensible, raced and dominant-(un)identified—were having church in the wild. They were enacting a gospel message by seeing, and singing, about their friend in jail, even while threats on the opposite coast emerged to halt the rise of a Black (Panther) Messiah. Fred Moten calls this “Black Kant (Pronounced Chant).” They put on long BLACK robes as outfits of rapture to prepare for the 1000 Deaths of a coward while they die once as soldiers. Somebody shout, “YEAH!”

What arrests the viewer is precisely the fact that their uniformity united them. Ericka said, “We had swag.” Akua said, “It was a rhythm to how we spoke, it was a rhythm to how we walked, and the people recognized that—we stood out! Outside of that, on the street, they ‘Ooh that’s a butt ugly person—ooh they ugly!’ But in the Party, it was just something that gave them this tremendous sex appeal.”

This reminds me of a moment in The Cider House Rules when Dr. Larch impresses upon Homer to “be of use.” This aesthetic conceit is suggestive of what the songs say, in a seamless blur, to invoke the spirit: you don’t have to be a star, baby, to be in the Party because simply by being in the Party, baby, every Panther is a star! This is being of use. Moreover, I recently did a talk about Jean-Michel Basquiat and his crowns and addressed my worry that the newfound commercial resurgence of his artistic mode may be an act of disembodiment—all Basquiat’s crowns were atop heads. I say that to say, part of what the documentary teaches is that regardless of becoming aware of one’s hair and finding a lightweight (p)leather jacket to brave the California sun, under every afro is a brain that thinks and behind every jacket or turtleneck is a heart that beats, bones that could be broken from word and deed.

In other words, the beauty of a movement like this one is not only that beautiful people were the faces of the organization, but also that people were made beautiful by association. Beautiful men cook breakfast and clean panther pads while handsome women arm themselves and administrate official business. These subjects are the embodiment, as persons, of panthers—“The panther doesn’t strike anyone but when he’s assailed upon, he’ll back up first. But if the aggressor continues, then he’ll strike out.”

The documentary backs up first and then strikes out through a series of revelations: MLK standing beside Stokely/Kwame as he states, “You tell dem white folk in Mississippi that all the scared niggers are dead!” (Have we ever really known Martin?); Elaine’s inclusion in the documentary, even while deemed “condemnable”; The Panthers walking into a government building with heavy armament, something that now seems unfathomable without bloodshed when done by “us”; Bobby and Huey as Jekyll and Hyde; Eldridge calling Reagan “a punk, a sissy, and a coward” only to endorse his presidency post-conversion; for the better part of a decade, any public proclamations always staying “on message” as if there was a script everyone read from; the multiraciality of the Party’s support; Kathleen’s black beauty love speech; Julian saying he may become a Panther “the day after” in optimal signifying posture; Panthers joining the Party so very, very young; 84% of COINTELPRO actions being enacted upon these so very, very young; Ora and Phyllis literally mothering while engaged in Panther labor; the firsthand epistolary moments, especially the young woman’s stating that men and women perpetuating patriarchy could get gone; the Party’s populace of women rivaling that of the modern-day Judeo-Christian church; Emory and his gorgeously fragmented icons projecting the whole aesthetic narrative of black American life; the little black girl resounding, “Fuck you pig!”; portraiture of Huey hanging in classrooms like the Honorable Elijah Muhammad hung in mosques, adding to Huey’s mythic status; Little Bobby Hutton, and his death still haunting Big Man; Marlon Brando engaging in critical whiteness studies; the white woman fundraising for The Panther Defense Fund; The Panther 21 being in jail for 2+ years; subaltern Bobby speaking even when gagged; Fred’s rhetorical prowess and coalition building in Chicago across lines of race and class; Fred having his Mason Temple moment a la King; the architecture of assassination at police headquarters; Chicago citizens surveying the scene of the crime as museum curation because the police were just that negligent; William O’Neal’s $300 recompense in the killing of Fred, those three Benjamins being the inflated amount of the antiquated 30 pieces of silver; the public shootouts and how their retellings transport the actors back to those exact moments, i.e., when Peaches waved the white flag, and shots sounded like a sonata; the excommunication of the Panther 21 over misappropriated funds; the FBI getting its way; the telephonic battle from Algiers between Huey and Eldridge; the secondary political moves taken by Bobby and Elaine; the celebration at Bobby’s campaign office after defeat; Huey organizing crime; the toll the movement and incarceration takes on one’s mental state; Ericka saying goodbye; the strength and weakness of the Party being its ideals, its youthful vigor, and its enthusiasm; Bobby’s noticeable absence throughout the project, even as he continues community activism today; there are still Panthers in prison today—this is a documentary chronicling the Vanguard, exhibiting how people could be of use. The doing of so much with so little. But my nostalgia gently creeps.

If the parable of the elephant teaches anything it is that blindness, specifically when one has sight, can create one helluva hermeneutic. This is to say: I went to the archive, having recalled many a Saturday afternoon as a child watching reruns of old television shows, and recalled that the Black Panther Party actually made its way into high Americana! There is perhaps nothing more pop cultural than the Partridge Family in the mid- to late-twentieth century. Couple the Panther aesthetic on the episode with the likes of Richard Pryor and Louis Gossett, Jr., making a cameo on bubblegum TV and what bottoms out is: in all the ways one presumes that “we” are “known”, people have substituted legacies for lies, living in the willful unknown, such that even today, the appearance of Panther association could merit censure to the point of international non-entry.

Moreover, it is precisely that willful unknown that makes me wonder whether those PBS viewers had at least a modicum of knowledge about the Party—who was the documentary for anyway? Is educating viewers about something they can have a general conversation about education at all, or simply nostalgia as homage? Perhaps the documentary aims at enlivening again those who have a panther ethic in order to acknowledge that although color, as uniform, and kind are not synonymous, that should not be a hindrance for doing one’s work in the cause of animating the person through the ruse of animality. Simultaneously, the project may also hope that those without education will watch insofar as the end result of viewing will be taming the wildebeests of fabrication.

+++

I. Augustus Durham is a third-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Published on February 22, 2016 11:58

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.