How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Person--On 'Vanguard of the Revolution'

“ . . . ; all you had to be was a human being.”: How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Personby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“ . . . ; all you had to be was a human being.”: How the Animality of the Panther Is a Ruse for the Animation of the Personby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)I could not help hearing my mother’s voice throughout the airing of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. She kept uttering: 1) “Growing up, we had so little yet did so much; now we have so much yet do so little”, and 2) “Just because we wear the same uniform does not mean we are united.” Perhaps the former quip is more apropos to then as the latter is to now, or maybe not, which is something I would debate, with anyone. Nonetheless, while watching Tuesday night, I fell into that ever-lingering affect that can be generative or detrimental: I became nostalgic.

We live in a society where some animals are treated better than others. (Look where the others live!) Furthermore, some people presume some animals to be more human than humans, hence those animals’ more humane treatment and societal reception. Yet this project forces us to wrestle with being summoned as character witnesses in the case of that all-too-familiar literary trope of the human versus nature. It appears, however, that the verdict is not guilty—the agential calculation to pose as, not “be”, an animal, a black panther to be exact, exemplifies the full spectrum of human expression and its condition as adjudicated by a jury of one’s peers.

The animality of the panther is a ruse for the animation of the person.

Some people, unfortunately, still do not get that.

Where the others live, there are proverbs. Proverbs and parables. Parables about elephants. A parable about elephants analogizes the party of black panthers. A party of panthers is akin to a pride of lions. These are collective nouns that capture in miniature a collectivity, its spirit. Another proverb from where the others live: the spirit will not descend without song.

Listening to the collective sing about, call forth, an other’s freedom—“FREE HUEY!”—takes on religious interpretation such that these Panthers—young and old, educated and sensible, raced and dominant-(un)identified—were having church in the wild. They were enacting a gospel message by seeing, and singing, about their friend in jail, even while threats on the opposite coast emerged to halt the rise of a Black (Panther) Messiah. Fred Moten calls this “Black Kant (Pronounced Chant).” They put on long BLACK robes as outfits of rapture to prepare for the 1000 Deaths of a coward while they die once as soldiers. Somebody shout, “YEAH!”

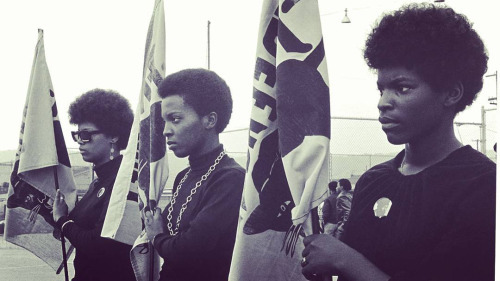

What arrests the viewer is precisely the fact that their uniformity united them. Ericka said, “We had swag.” Akua said, “It was a rhythm to how we spoke, it was a rhythm to how we walked, and the people recognized that—we stood out! Outside of that, on the street, they ‘Ooh that’s a butt ugly person—ooh they ugly!’ But in the Party, it was just something that gave them this tremendous sex appeal.”

This reminds me of a moment in The Cider House Rules when Dr. Larch impresses upon Homer to “be of use.” This aesthetic conceit is suggestive of what the songs say, in a seamless blur, to invoke the spirit: you don’t have to be a star, baby, to be in the Party because simply by being in the Party, baby, every Panther is a star! This is being of use. Moreover, I recently did a talk about Jean-Michel Basquiat and his crowns and addressed my worry that the newfound commercial resurgence of his artistic mode may be an act of disembodiment—all Basquiat’s crowns were atop heads. I say that to say, part of what the documentary teaches is that regardless of becoming aware of one’s hair and finding a lightweight (p)leather jacket to brave the California sun, under every afro is a brain that thinks and behind every jacket or turtleneck is a heart that beats, bones that could be broken from word and deed.

In other words, the beauty of a movement like this one is not only that beautiful people were the faces of the organization, but also that people were made beautiful by association. Beautiful men cook breakfast and clean panther pads while handsome women arm themselves and administrate official business. These subjects are the embodiment, as persons, of panthers—“The panther doesn’t strike anyone but when he’s assailed upon, he’ll back up first. But if the aggressor continues, then he’ll strike out.”

The documentary backs up first and then strikes out through a series of revelations: MLK standing beside Stokely/Kwame as he states, “You tell dem white folk in Mississippi that all the scared niggers are dead!” (Have we ever really known Martin?); Elaine’s inclusion in the documentary, even while deemed “condemnable”; The Panthers walking into a government building with heavy armament, something that now seems unfathomable without bloodshed when done by “us”; Bobby and Huey as Jekyll and Hyde; Eldridge calling Reagan “a punk, a sissy, and a coward” only to endorse his presidency post-conversion; for the better part of a decade, any public proclamations always staying “on message” as if there was a script everyone read from; the multiraciality of the Party’s support; Kathleen’s black beauty love speech; Julian saying he may become a Panther “the day after” in optimal signifying posture; Panthers joining the Party so very, very young; 84% of COINTELPRO actions being enacted upon these so very, very young; Ora and Phyllis literally mothering while engaged in Panther labor; the firsthand epistolary moments, especially the young woman’s stating that men and women perpetuating patriarchy could get gone; the Party’s populace of women rivaling that of the modern-day Judeo-Christian church; Emory and his gorgeously fragmented icons projecting the whole aesthetic narrative of black American life; the little black girl resounding, “Fuck you pig!”; portraiture of Huey hanging in classrooms like the Honorable Elijah Muhammad hung in mosques, adding to Huey’s mythic status; Little Bobby Hutton, and his death still haunting Big Man; Marlon Brando engaging in critical whiteness studies; the white woman fundraising for The Panther Defense Fund; The Panther 21 being in jail for 2+ years; subaltern Bobby speaking even when gagged; Fred’s rhetorical prowess and coalition building in Chicago across lines of race and class; Fred having his Mason Temple moment a la King; the architecture of assassination at police headquarters; Chicago citizens surveying the scene of the crime as museum curation because the police were just that negligent; William O’Neal’s $300 recompense in the killing of Fred, those three Benjamins being the inflated amount of the antiquated 30 pieces of silver; the public shootouts and how their retellings transport the actors back to those exact moments, i.e., when Peaches waved the white flag, and shots sounded like a sonata; the excommunication of the Panther 21 over misappropriated funds; the FBI getting its way; the telephonic battle from Algiers between Huey and Eldridge; the secondary political moves taken by Bobby and Elaine; the celebration at Bobby’s campaign office after defeat; Huey organizing crime; the toll the movement and incarceration takes on one’s mental state; Ericka saying goodbye; the strength and weakness of the Party being its ideals, its youthful vigor, and its enthusiasm; Bobby’s noticeable absence throughout the project, even as he continues community activism today; there are still Panthers in prison today—this is a documentary chronicling the Vanguard, exhibiting how people could be of use. The doing of so much with so little. But my nostalgia gently creeps.

If the parable of the elephant teaches anything it is that blindness, specifically when one has sight, can create one helluva hermeneutic. This is to say: I went to the archive, having recalled many a Saturday afternoon as a child watching reruns of old television shows, and recalled that the Black Panther Party actually made its way into high Americana! There is perhaps nothing more pop cultural than the Partridge Family in the mid- to late-twentieth century. Couple the Panther aesthetic on the episode with the likes of Richard Pryor and Louis Gossett, Jr., making a cameo on bubblegum TV and what bottoms out is: in all the ways one presumes that “we” are “known”, people have substituted legacies for lies, living in the willful unknown, such that even today, the appearance of Panther association could merit censure to the point of international non-entry.

Moreover, it is precisely that willful unknown that makes me wonder whether those PBS viewers had at least a modicum of knowledge about the Party—who was the documentary for anyway? Is educating viewers about something they can have a general conversation about education at all, or simply nostalgia as homage? Perhaps the documentary aims at enlivening again those who have a panther ethic in order to acknowledge that although color, as uniform, and kind are not synonymous, that should not be a hindrance for doing one’s work in the cause of animating the person through the ruse of animality. Simultaneously, the project may also hope that those without education will watch insofar as the end result of viewing will be taming the wildebeests of fabrication.

+++

I. Augustus Durham is a third-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Published on February 22, 2016 11:58

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.