Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 641

February 22, 2016

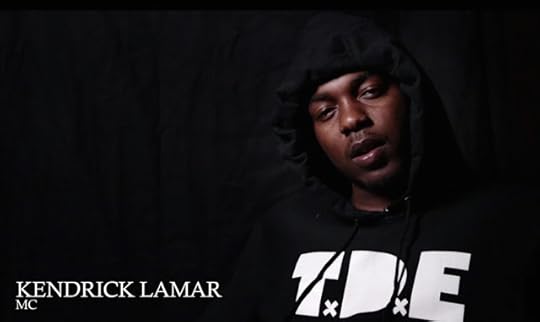

The Hip-Hop Fellow Outtakes: Kendrick Lamar Talks Hip-Hop Education

In this outtake from The Hip-Hop Fellow, Kendrick Lamar discusses his Hip-Hop Education.

The Hip-Hop Fellow

is a feature length documentary following Grammy Award winning producer 9th Wonder's tenure at Harvard University. Interviewees include Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Kendrick Lamar, Young Guru, Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, Phonte, Dr. Marcyliena Morgan, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Ab-Soul, Rapper Big Pooh & DJ Premier.

In this outtake from The Hip-Hop Fellow, Kendrick Lamar discusses his Hip-Hop Education.

The Hip-Hop Fellow

is a feature length documentary following Grammy Award winning producer 9th Wonder's tenure at Harvard University. Interviewees include Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Kendrick Lamar, Young Guru, Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, Phonte, Dr. Marcyliena Morgan, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Ab-Soul, Rapper Big Pooh & DJ Premier.The Hip-Hop Fellow Outtakes - Kendrick Lamar Talks Hip-Hop Education from Pricefilms on Vimeo.

Published on February 22, 2016 09:37

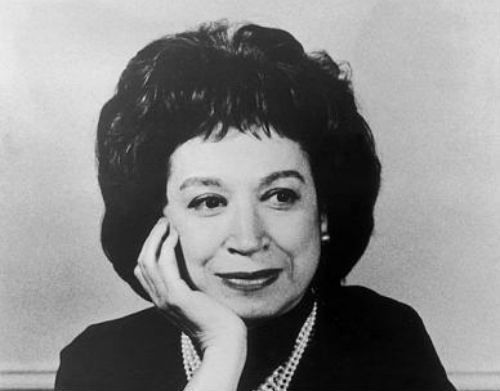

Live from the Reading Room: Love Letter from Nathan Woodard to Alice Childress

'This episode of

Live from The Reading Room

features an excerpt of a love letter from musician and composer Nathan Woodard to his wife and creative collaborator Alice Childress, who was also an actress, novelist, poet, playwright and American Negro Theatre member. Linden Anderson, Library Technical Assistant III in our Photographs and Prints Division, reads the letter aloud.' -- +Schomburg Center

'This episode of

Live from The Reading Room

features an excerpt of a love letter from musician and composer Nathan Woodard to his wife and creative collaborator Alice Childress, who was also an actress, novelist, poet, playwright and American Negro Theatre member. Linden Anderson, Library Technical Assistant III in our Photographs and Prints Division, reads the letter aloud.' -- +Schomburg Center

Published on February 22, 2016 03:50

The Lyricism of James Baldwin

In this special episode of

Left of Black on the Root

, Guest host and Duke Professor Tsitsi Ella Jaji interviews Ed Pavlić about his latest work,

Who Can Afford to Improvise?: James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners

(Fordham University Press, 2015). Pavlić is a poet, author, and a Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Georgia.

In this special episode of

Left of Black on the Root

, Guest host and Duke Professor Tsitsi Ella Jaji interviews Ed Pavlić about his latest work,

Who Can Afford to Improvise?: James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners

(Fordham University Press, 2015). Pavlić is a poet, author, and a Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Georgia.

Published on February 22, 2016 03:18

February 21, 2016

Revolution Starts At Home: RodStarz of Rebel Diaz Talks Solo Album Free Family Portraits

'Rodrigo Starz is one half of Bronx-based political Hip Hop duo Rebel Diaz. He spoke with Jesse Menendez about his upcoming solo project called Free Family Portraits, which tackles personal themes and allows Starz to finesse his lyricism over more traditional Boom-Bap style beats.' --

Vocalo

'Rodrigo Starz is one half of Bronx-based political Hip Hop duo Rebel Diaz. He spoke with Jesse Menendez about his upcoming solo project called Free Family Portraits, which tackles personal themes and allows Starz to finesse his lyricism over more traditional Boom-Bap style beats.' --

Vocalo

Published on February 21, 2016 12:23

Talking Music: Blitz the Ambassador & Yaba Blay on Space + Place + Diaspora

During his artistic residency at Duke University, musician and filmmaker

Blitz the Ambassador

sat down with scholar + activist

Yaba Blay

in a conversation about music and Diaspora at the Duke Forum for +Scholars and Publics.

During his artistic residency at Duke University, musician and filmmaker

Blitz the Ambassador

sat down with scholar + activist

Yaba Blay

in a conversation about music and Diaspora at the Duke Forum for +Scholars and Publics.

Published on February 21, 2016 08:02

February 20, 2016

"Standing on the Wrong Side of History"-- An Open Letter of Rep. John Lewis by Monica Moorehead

"Standing on the Wrong Side of History"-- An Open Letter of Rep. John Lewisby Monica Moorehead | @mmashcat | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

"Standing on the Wrong Side of History"-- An Open Letter of Rep. John Lewisby Monica Moorehead | @mmashcat | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Dear Brother John Lewis,

I am a Black woman, who, like you, was born in Alabama at the dawn of the modern day Civil Rights Movement. My parents supported the Montgomery Bus Boycott. I, like millions of others, suffered through the indignities of Jim Crow, including watching, as an adolescent, my mother being “escorted” out of a white-only public bathroom by the police.

So I understand firsthand and respect your bravery and your contribution to the Black freedom struggle.

I know that half a century ago, you were nearly beaten to death when state troopers and Klansmen attacked the march from Selma to Montgomery.

Back then, you faced the reality of racist violence and the possibility of your own death on a daily basis. Back then, you were in the vanguard of the Civil Rights revolution. Nobody can ever take that away from you.

With all due respect, however, what you did the other day during the announcement of the Black Congressional Caucus Political Action Committee’s support for the candidacy of Hillary Clinton was counterrevolutionary.

The problem isn’t that you didn’t see Bernie Sanders at the 1963 March on Washington or during the freedom rides. The problem is that you are not seeing the millions of young people, especially young Black people and other people of color, who are using the Sanders campaign to send a message to the capitalist political establishment.

They are using the Sanders campaign to say they are tired of waiting for justice. They are using the Sanders campaign to say they are sick and tired of young people of color being murdered for the crime of walking, talking, or driving while Black.

They are saying they are tired of the police war on Black America, and they are tired of mass incarceration.

They are saying they are not willing to support establishment politicians merely because some of us have known them.

They are saying they don’t want to be told to stay in their place, to be patient, to be realistic and support the status quo. They are saying they want more than the false promises of incremental change; they demand radical, revolutionary change and they want it NOW.

Bernie Sanders refers to himself as a socialist (that’s good because it has people talking about socialism). Actually he’s more of a New Deal liberal.

I’m a real socialist, a revolutionary socialist with a capital S. I believe that the Democratic Party is a political prison for the workers and oppressed, because, just like the Republican Party, it is controlled by and serves the interests of capitalism.

Frankly, Sanders is not great on racism. He’s said that he opposes reparations for Black people to compensate for the crimes against them dating back to slavery. It’s taken considerable pressure to get Sanders to take the struggle against racism seriously. And he still has a long way to go.

But within the narrow confines of the Democratic Party, next to Hillary Clinton, who personifies the political establishment, Sanders looks radical.

Sure, Clinton has felt the pressure to give more lip service to fighting racism, sexism, and LGBTQ oppression.

But Clinton’s real campaign message is that radical change is unrealistic and she’s the realistic candidate.

I’m sure, Brother Lewis, that when you were young, you were on the receiving end of many lectures about the need to be “realistic” and to be “patient.” You remember when older Civil Rights leaders made you tone down your speech at the 1963 march on Washington because they felt it was too militant.

You remember your just criticism of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because it did not address the prevalence of racist police brutality. Surely you remember all the times you were told to slow down, cool down, and follow the lead of the older leaders.

Indeed, 50 years ago this year, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was formed in part because old guard Civil Rights leaders were not doing anything to stop police violence against Black people.

On the surface, this all seems like a generational struggle, and to some extent, it is. But it’s more than that. It’s a struggle between those who stand with the capitalist establishment and those who demand radical change.

I still respect your contribution to our struggle for freedom. But this time, Brother Lewis, sadly, you are standing on the wrong side of history.

Respectfully,

Monica MooreheadWorkers World Party 2016 presidential candidate

Published on February 20, 2016 06:13

February 19, 2016

Saul Williams on Martyrs + Movements

"I think of martyrs as the other 1%," poet and writer Saul Williams says in a conversation with +Watch LOUD about his thoughts on political martyrdom. His latest project is Martyr Loser King.

"I think of martyrs as the other 1%," poet and writer Saul Williams says in a conversation with +Watch LOUD about his thoughts on political martyrdom. His latest project is Martyr Loser King.

Published on February 19, 2016 05:57

February 18, 2016

Come Back, Chester Himes

Come Back, Chester Himesby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Come Back, Chester Himesby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)For an artist, who deftly redefined the contours of Soul music, Donny Hathaway’s most expansive use of his talents, might have been for the soundtrack of a long-forgotten Blaxploitation film, based on the writings of a not-nearly-remembered enough Black novelist.

Out-of-print for nearly three decades, the original motion picture soundtrack for Come Back Charleston Blue serves as a reminder of the era of Blaxpolitation—the moment in the late 1960s that marks the beginning of mainstream America’s fascination with under/other-worldly Blackness—but highlights the work of an often overlooked genius of black expressive culture, Chester Himes.

In his own right Chester Himes was one of the great literary figures of the 20th century. His first two novels, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945) and Lonely Crusade (1947), though roundly dismissed at the time of their publication—Ebony Magazine called Himes a “psychopath” in a review of the latter—they have since become part of the canon of 20th century African-American literature, as is also the case with Himes’s two autobiographies The Quality of Hurt (1973) and My Life of Absurdity (1976).

Born in Jefferson City, Missouri in 1909, Himes began writing professionally, while he was in prison for armed burglary. Two short stories, “Crazy in the Stir” and “To What Red Hell” were published in 1934 by Esquire Magazine while Himes was a 25-year-old inmate. His experiences in prison, logically informed Himes’s decision to write as a social realist—capturing the less savory of aspects of Black American life, without a hint of irony or luster.

When Himes moved to Los Angeles in the early 1940s, hoping to find work as a Hollywood scribe, he turned to the shipyards of Los Angeles and what writer RJ Smith calls the “The Great Black Way” to find inspiration. “The Great Black Way” was Los Angeles’s “Central Avenue” which rivaled Harlem’s Lennox Avenue and Chicago’s “Stroll” in the mythology of mid-20th century urban Blackness. It was this world that Himes partly captured in his first novels and it would be this world that would fuel Himes imagination a decade later as he sat in exile in France.

After the commercial failure of his first two novels Himes headed abroad to France, mainly to salve his hurt feelings and depression. While in exile Himes turned to crime fiction and it was through his detective novels, set in the contemporary 1950s and 1960s, that Himes remained wedded to the intricacies of everyday Blackness.

Himes famously once described his main occupation as “the search for money,” as some have come to think of his crime novels an attempt to cash in quickly on his formidable writing skills—mid-20th century street-lit, if you will. The focal points of his nine crime-novels were a pair of “Harlem” detectives, Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson—characters who were based on two cops Himes had contact with on Central Avenue.

When Hollywood came calling for Himes—more than twenty years after Himes tried to sell scripts to Hollywood studios—it was those detective novels, in all their absurd glory, that became fodder in the Blaxploitation machine. The first of those novels depicted on screen was Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), which was directed by Ossie Davis, and starred Redd Foxx and Calvin Lockhart. Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson were brought to life by Godfrey Cambridge (Watermelon Man) and Raymond St. Jacques. The duo reprised their roles when the Samuel Goldwyn company turned Himes’s “The Heat is On” into Come Back Charleston Blue (1972). Himes voiced little regret in having his work serving a machine that so many felt belittled African-American culture.

It was as a child, sitting in the theater with my parents, watching Cotton Come to Harlem and Come Back Charleston Blue that I was first introduced to Chester Himes (though the streets of Harlem were the real stars of those movies). It would be a decade later, as I college student, that I heard poet and Third World Press founder Haki Madhubuti reference the genius of Himes that occurred well before those movies were made. For all of the criticisms that could have been made about how exploitive the Blaxploitation film genre was, this was an instance, like Hathaway’s soundtrack, where it created a portal to something more compelling.

In his wonderful book The Great Black Way: L.A. in the 1940s and the Lost African American Renaissance (2006), RJ Smith writes of Himes, “the last thing he was interested in was being a role model, in ‘representing the race.’ That was the burden of those elegant Harlem Renaissance writers whose pictures [Himes] was turning to the wall.”

Chester Himes died in 1984.

Published on February 18, 2016 08:07

February 17, 2016

The Third Space: Episode 6 with Bryant Terry

'Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership Award-winning chef, educator, and author renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just, and sustainable food system. He is currently the inaugural Chef in Residence at the

Museum of the African Diaspora

(MoAD) in San Francisco where he creates programming that celebrates the intersection of food, farming, health, activism, art, culture, and the African Diaspora.' -- +Blavity

'Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership Award-winning chef, educator, and author renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just, and sustainable food system. He is currently the inaugural Chef in Residence at the

Museum of the African Diaspora

(MoAD) in San Francisco where he creates programming that celebrates the intersection of food, farming, health, activism, art, culture, and the African Diaspora.' -- +Blavity

Published on February 17, 2016 20:29

You Don’t Need White Approval: Why the Oscars & Grammys Don’t Appreciate Black Art by Law Ware

You Don’t Need White Approval: Why the Oscars & Grammys Don’t Appreciate Black Artby Law Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

You Don’t Need White Approval: Why the Oscars & Grammys Don’t Appreciate Black Artby Law Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Racism is a white problem. Yes, the nature of racism and the system of white supremacy is such that sun kissed populaces often experience the underside of the American democratic experiment, but, I maintain, racism is a white problem.

Those accustomed to white supremacy are terrified by black political and cultural self-sufficiency. Part of what made the Black Panthers so terrifying was their lack of interest in what white folks thought of what they said or how they lived. A sure way to become divisive is to live in a way that centers blackness, not whiteness. What is ironic about this fear is that individuals who pushed back against white supremacy are the ones that moved America toward actualizing her ideals.

Black folks advocating for the right to vote, to attend a desegregated school, to overcome housing segregation were all doing a service to this democratic experiment. Black Americans are a major part of why America has the potential to be great. You can have Abraham Lincoln and George Washington, give me Stokely Carmichael and Ella Baker. Some of the greatest Americans have been black men and women advocating and agitating for their rights. Yet, despite this truth, many today engage in practices that center whiteness.

When we need the approval and validation of the dominant group in order for us to see our own work as valuable and worthy, we engage in a vicious form of internalized racism—one that centers whiteness even as we engage in the subversive work of expressing black brilliance.

This begs the question: Do we have the ability to live free of white supremacist thinking? Can we see and appreciate black beauty without the oppressive lens of euro-normativity filtering our gaze? Are we able to validate achievement without whiteness as the standard for excellence?

Of late, much attention has been paid to the racial homogeneity of the Academy Awards. For the second year in a row, the nominees in the major acting categories have been all white. There are calls to boycott the Oscars, and the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite has been trending now for months. This is reminiscent of a few years ago when there was outrage over Macklemore’s The Heist sweeping the rap category at the 2014 Grammy Awards. Many were critical of the Grammys because Kendrick Lamar’s beautiful, polyvalent Good kid, M.A.A.D. City was largely ignored.

This did not surprise me. There is historical precedent of white folks being celebrated for appropriating black culture. That’s why Elvis Presley is honored and not Big Mamma Thornton. That’s why Led Zeppelin is celebrated while Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon are largely forgotten. That’s why the Beach Boys’s Surfin USA is cherished and Chuck Berry’s Sweet Sixteen is barely remembered. Most white Americans want a black sound and black culture without actual black people.

Too often we sit at the door of White America asking them to recognize us. We perpetually celebrate the first of us that white folks allowed to hold a position. We are consistently outraged when white institutions do what they were created to do and marginalize people of color. We constantly demean and ghettoize the NAACP Image Awards, the BET Awards, and other spaces that have historically made room for and celebrated black brilliance.

When you convey more worth to white access and recognition than you do to black affirmation, you participate in your own oppression. We need to support, protect, and prioritize those spaces that celebrate our blackness, not award shows that tokenize our culture.

At the 2016 Grammy Awards, Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly was recognized five times, but Taylor Swift’s catchy, yet shallow 1989 garnered her second Grammy for Album of the Year. While I’m happy for him, we should never use a white standard of excellence to assess black talent. TPAB, like Beyonce’s “Formation”, was not made for white people—and I do not expect White institutions to celebrate it.

I am reminded of the words W.E.B. Du Bois wrote to eulogize the brilliant scientist Carter G. Woodson: “No white university ever recognized his work; no white scientific society ever honored him. Perhaps this was his greatest honor.” When white institutions fail to appreciate the work of black folks, we should not be outraged. We should consider it an honor.

+++

Lawrence Ware is an Oklahoma State University Division of Institutional Diversity Fellow. He teaches in OSU's philosophy department and is the Diversity Coordinator for its Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to the publication The Democratic Left and contributing editor of the progressive publication RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race and politics for the Huffington Post Live, NPR's Talk of the Nation, and PRI’s Flashpoint. Follow him on Twitter: @law_ware

Published on February 17, 2016 19:50

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.