Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 629

April 8, 2016

#TheSpin: Making Bank from Bondage + "Black Girl is a Verb"

On this episode of #TheSpin with host Esther Armah, she is joined by Joan Morgan and Monifa Bandele in a discussion of the connection between private prisons and mass incarceration, and Brittney Cooper's article "Black Girl is a Verb".

On this episode of #TheSpin with host Esther Armah, she is joined by Joan Morgan and Monifa Bandele in a discussion of the connection between private prisons and mass incarceration, and Brittney Cooper's article "Black Girl is a Verb".

Published on April 08, 2016 19:43

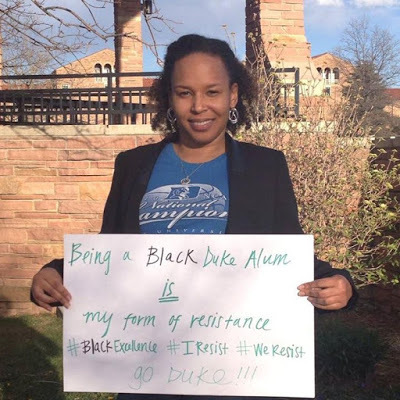

“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workers

“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workersby Bianca Williams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workersby Bianca Williams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)A few days ago, FB let me know it has been a year since I posted the above pic. Taken after hearing from Black Duke undergrads that they found a noose hanging from a tree on campus, but before our 2015 men's basketball championship, I posted this message to be in solidarity with the students: "Yes, I taught [at CU Boulder] in my 2010 championship shirt today. Got lots of side-eye. Duke hate is real, but hilarious. Racism is real and terribly sad. Duke, I love you. But we gotta do better. So win the championship, and then let's get on that MANDATORY critical race and inequities class for students AND faculty. Being a BLACK Duke alum is my form of resistance."

As a former Duke student, and now as an alum, I am constantly aware that Du Bois' concept of “double-consciousness” and Crenshaw’s “intersectionality” are still relevant. That my love for an institution that provided me with an amazing education; a group of brilliant life-long friends; resources to dream big and think critically; a beautiful living and learning environment; generous and fierce mentors and advisors; and the experience of watching the best basketball teams in the country (both women’s and men’s, and always!), is deeply interwoven, and sometimes predicated, on my position as a second-class member of this community as a Black (including Caribbean!), first-generation college-educated woman.

My mind, body, and spirit recognized and felt the plantation politics of Duke before I had the words or analysis to comprehend the different aspects of it. I understood that in many ways Duke’s institutional and social culture was grounded on extracting, underpaying, and undervaluing the physical and emotional labor of thousands of its employees. I was hyper aware of my internal conflict and tension as I experienced the social capital and privilege bestowed on me as I matriculated into the Duke community. I remember the shock I felt when a professor told me that once I graduated from Duke, I would no longer be a part of the working-class community I still saw myself as an active member of, simply because of the economic and social capital of Duke’s name and my degree. To this day I tell my students that I’m “hesitantly middle-class, and learning every day what that means.”

At Duke, I sometimes found myself feeling more comfortable with the staff at the Marketplace or in the dorms than fellow students or professors, because they reminded me of my mom, my aunties, my cousins, and where I came from. When I felt invisible, they saw me. It was the workers in Bassett who would stop me when I clearly had a bad day on campus, and would chat with me to lift my spirits. It was these workers who made sure I was okay when I couldn’t afford to go home on breaks. It was the workers in the East Campus store, and those that chilled with me on the Black bench during their breaks, who greeted me BY NAME. They STILL do whenever I return to campus and see some of them around the community. It was the Black women workers who empathized with me when I would pull all-nighters in the Friedl building, studying for preliminary exams and writing my dissertation during graduate school.

In fact in 2009, when I spent weeks ferociously writing from 10 pm to 6 am to finish my dissertation, it was these women who came to clean the building in the morning who would send me home as the sun came up. They would admonish me for not getting sufficient rest, while giving me pep talks about how I was going to finish and stating that they were proud of me. The day I pressed the “send” button and submitted my dissertation to my advisor, it was these women who knew first, and celebrated with me through my exhaustion and delirium.

Again, they let me know that I wasn’t invisible and that they saw me. And I saw them. I wouldn’t pass by without saying hello or giving a head nod. The Duke culture that taught me that somehow I was supposed to be better than them; that their humanity and their labor was supposed to be invisible; that our struggles in a deeply racialized and economically-oppressive space were not intertwined, was not acceptable to me. And my mom’s home-training wouldn’t allow me to ignore these things or these individuals who were a significant part of the Duke community.

I remember the exhaustion and frustration as I spent more hours in meetings with peers and administrators, resisting and protesting structures and a culture that was oppressive to the ENTIRE community, than in the classroom. I remember the sting of shame and isolation when I opened my school’s newspaper after Spring Break to find a full-page ad declaring that reparations for slavery are wrong and racist, and welfare was a form of “paying” African Americans reparations. I remember the apologetic, knowing looks I would give Black staff when students of all races treated them like “the help” in the cafeteria, on the bus, and on the quad. I remember the fear as I walked by benches of drunk, white fraternity men screaming (or whispering) racial epithets, simultaneously declaring their love for hip-hop, while sending leery glares over my Black feminine body.

I remember the anger burning in my belly when I knew that Black workers were going to have to clean up their trash and vomited mess in the morning. I remember being grateful as I sat on the Black bench and learned from a worker about the Duke plantation—plantation politics—for the first time, understanding there was a name for what I was experiencing and seeing. Duke, the institution and the community, taught me about racism and economic inequity both inside and outside the classroom, and Duke’s workers were a significant part of that education. I never forget those Black workers and students who made it possible for me to make it through to the other side.

This is why I send my full love and support to the students occupying the Allen Building, and the supporting workers and students in Abele-ville. My organizing energy goes to those students and workers demanding that the most vulnerable in our community get the resources they need and have earned. My “that’s right, say it again!” energy goes to those students that demand that all members of Duke’s community (especially well-paid and powerful administrators) are held to the standards and values that will eventually make Duke the amazing place it aspires to be. You all are doing remarkable and necessary work not only in the Duke community, but also in the nationwide community that is U.S. higher education. We are watching. We are learning. And you are teaching.

I am a member of Duke’s community. I am Forever Duke. I earned that right, and it is a lifelong membership. But know that being a Black Duke alum is a form of resistance for me. And as a member of Duke’s community, I feel it is my duty to love Duke in the Baldwinian-sense: to make you aware of the things you don’t see, and to perpetually critique you until you do better. Duke, you can try to wait this out if you want, but know that these students, and the Movement for Black Lives many of them are learning from, ain’t going anywhere.

***

Bianca Williams is Assistant Professor on Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is the author of the forthcoming Exporting Happiness (Duke University Press).

Published on April 08, 2016 16:36

Class, Race and Patriarchy: Lessons from The People vs. OJ Simpson by Lawrence Ware

Class, Race and Patriarchy: Lessons from The People vs. OJ Simpsonby Lawrence Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Class, Race and Patriarchy: Lessons from The People vs. OJ Simpsonby Lawrence Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)The People vs. OJ Simpson is a peculiar, brilliant series. It is an amazing examination of race, class, and gender set against the backdrop of social unrest and journalistic sensationalism. The writing is sublime and the acting exquisite. (If Courtney B. Vance is not given all the awards possible for his performance, there will be marching in the streets.) Yet, culturally, this is the show we need for three reasons.

We’ve been here before.

The People vs. OJ Simpson forces America to come to terms with the fact that the grievances expressed by those in the Movement for Black Lives are not new. The merciless beating of Rodney King is shown at the beginning of the series to frame all that comes thereafter, and the deep mistrust many in the black community have toward America’s criminal justice system colors every frame and scene. This mistrust set the stage for black Americans to root for a man that had all but abandoned them.

OJ Simpson was not deeply involved in the black community. He was not in the vanguard of movements for black social uplift. He became a symbol of the plight of black men and women struggling against forces of marginalization—and Johnnie Cochran understood what Simpson represented. When Cochran defended OJ, many of us felt that Cochran was defending us. Many of us wanted, just once, for a black man to be found innocent…even if he did the crime.

C.R.E.A.M.

I hope it is not a spoiler to say that OJ Simpson was found not guilty of the crimes for which he stood accused. I also hope it is not a spoiler to say that he would probably have been found guilty if it were not for his talented and well paid legal team. This series shows us that the financial standing of a defendant is almost as important, and in many ways more important, than said person’s guilt or innocence. The People vs. OJ Simpson is clear about the role money plays in the quality of a defense. If OJ were less wealthy and famous, I have no doubt he would have plead guilty and entered into an agreement with the district attorney’s office. Race, in this case, mattered, but socioeconomic status mattered more.

The pitfalls of blind racial allegiance

When the verdict was read, we saw footage of many black and brown people cheering in the streets while white folks reacted with disgust. A person approached the camera shouting, “Justice was served!” As a kid in middle school, I cheered. I high fived my friends; I felt confident that justice had, indeed, been served. However, here’s the thing: it hadn’t.

There was convincing evidence, both forensic and circumstantial, that OJ had committed the crimes. However, that evidence did not matter to many of us that lived through that moment in time. We were blinded by what OJ represented. We projected unto him our anger and frustration with an unjust and corrupt criminal justice system. We clothed him in our dreams of black validation in the face of white supremacy. We saw in him a chance to right centuries of wrongs—and because many of us either knew he was guilty and did not care or was blinded by racial allegiance, we celebrated when a guilty man went free. We were wrong. I was wrong.

We have no moral grounds to decry injustice in America while celebrating a miscarriage of justice for racial reasons. When we do that, we only empower forces that marginalize us. It is a temporary victory that brings more harm than good. Especially when we consider the clear misogyny displayed by Simpson and how many of us looked past the domestic violence to support a man who had clearly abused his wife. The critique of patriarchy lurking in the background of the series made the celebratory behavior displayed when he was declared not guilty all the more distasteful.

It has been a surreal experiencing watching a show that does not find its tension in hiding from viewers the twists and turns of the plot, but, rather, by unveiling the complexities of a flawed system peopled by imperfect human beings. OJ Simpson got away with murder, but this time, I was not guilty of looking past the misdeeds of a guilty man.

***

Lawrence Ware is an Oklahoma State University Division of Institutional Diversity Fellow. He teaches in OSU’s philosophy department and is the Diversity Coordinator for its Ethics Center. An advisor to Democratic Left and contributing editor at RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race and politics for the Huffington Post Live, NPR’s Talk of the Nation, and PRI’s Flashpoint. He is an ordained minister in the Progressive Baptist Convention. Find him on Twitter @law_ware.

Published on April 08, 2016 08:02

Sounds + Sonics: Gregory Porter--"Don't Lose Your Steam" (2016)

Published on April 08, 2016 03:47

April 5, 2016

Left of Black S6:E24: What is the Art of Cool Festival? A Celebration of Music + Innovation

Left of Black S6:E24: What is the Art of Cool Festival? A Celebration of Music + Innovation

Left of Black S6:E24: What is the Art of Cool Festival? A Celebration of Music + InnovationLeft of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in-studio by Cicely Mitchell (@drcicy), co-founder of the Art of Cool Project and co-curator of the Art of Cool Festival. Billed as progressive jazz and alternative soul music festival located in downtown Durham, NC, the Art of Cool Festival runs from May 6-8 and is headlined by Grammy Award winning Jazz Artist Terence Blanchard and The Internet.

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on April 05, 2016 20:24

April 2, 2016

Vocalo: Eryn Allen Kane on Live From Studio 10

'Singer Eryn Allen Kane has been gaining national attention as one of the newest powerful voices to come out of Chicago. Soulful yet assertive, Eryn’s voice can be heard on a number of collaborations, including that with the one and only Prince, as well as on her own recent releases – Aviary Acts I and II. We’re excited to welcome Eryn in our studio for a special , stripped down performance – just her voice and the guitar.' -- Vocalo

'Singer Eryn Allen Kane has been gaining national attention as one of the newest powerful voices to come out of Chicago. Soulful yet assertive, Eryn’s voice can be heard on a number of collaborations, including that with the one and only Prince, as well as on her own recent releases – Aviary Acts I and II. We’re excited to welcome Eryn in our studio for a special , stripped down performance – just her voice and the guitar.' -- Vocalo

Published on April 02, 2016 06:50

#TheRemix: Michael Eric Dyson on How Race Shapes Our Perception of the Obama Administration

'

#TheRemix

Host James Braxton Peterson and author Michael Eric Dyson discuss Dyson's new book, The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America. Their conversation took place in front of a live audience as part of The Free Library of Philadelphia Author Events series.'

'

#TheRemix

Host James Braxton Peterson and author Michael Eric Dyson discuss Dyson's new book, The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America. Their conversation took place in front of a live audience as part of The Free Library of Philadelphia Author Events series.'

Published on April 02, 2016 06:44

MarketPlace: How Marriott Buying Starwood Affects Frequent Travelers

'Since Marriott International announced its intent to acquire Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide in November, speculation has run wild about the impact on Starwood customers. Luckily, there’s been plenty of news to follow.' -- +Marketplace APM

'Since Marriott International announced its intent to acquire Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide in November, speculation has run wild about the impact on Starwood customers. Luckily, there’s been plenty of news to follow.' -- +Marketplace APM

Published on April 02, 2016 06:27

The Art of Cool Festival--Black Arts + Innovation in Durham, North Carolina (May 6-8)

On this episode of

Left of Black on The Root

, host Mark Anthony Neal sits downs with Cicely Mitchell, co-curator of

The Art of Cool Festival

in Durham, NC (May 6-8). The Festival, in its third year, features concerts and innovation workshop. This year's headliners are Grammy Award winning Jazz Artist

Terence

Blanchard

and

The Internet

.

On this episode of

Left of Black on The Root

, host Mark Anthony Neal sits downs with Cicely Mitchell, co-curator of

The Art of Cool Festival

in Durham, NC (May 6-8). The Festival, in its third year, features concerts and innovation workshop. This year's headliners are Grammy Award winning Jazz Artist

Terence

Blanchard

and

The Internet

.

Published on April 02, 2016 05:58

April 1, 2016

Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts on Does a Presidential Candidate's Religion Matter?

'Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts, pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, explains why religious faith is a small matter for him when choosing who to vote for political office.' -- +The Greene Space at WNYC & WQXR

'Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts, pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, explains why religious faith is a small matter for him when choosing who to vote for political office.' -- +The Greene Space at WNYC & WQXR

Published on April 01, 2016 20:39

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.