Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 625

April 18, 2016

7th Avenue Project: George Yancy on Philosophizing While Black

'“As a black male in the United States,” says George Yancy, “to do philosophy in the abstract would be to deny the reality of my own existence.” Yancy grew up in a tough North Philadelphia housing project, where young men were far more likely to end up in early graves or jail than in academia. He beat the odds and now enjoys the status of a tenured professor at a major university, but he hasn't forgotten where he came from, or the racial realities that made his story so unlikely. On the

7th Avenue Project

Yancy talks about his beginnings, becoming a philosopher and using his brand of "down to earth" philosophizing to explore the structure of blackness, whiteness and lived experience in a racialized society.'

'“As a black male in the United States,” says George Yancy, “to do philosophy in the abstract would be to deny the reality of my own existence.” Yancy grew up in a tough North Philadelphia housing project, where young men were far more likely to end up in early graves or jail than in academia. He beat the odds and now enjoys the status of a tenured professor at a major university, but he hasn't forgotten where he came from, or the racial realities that made his story so unlikely. On the

7th Avenue Project

Yancy talks about his beginnings, becoming a philosopher and using his brand of "down to earth" philosophizing to explore the structure of blackness, whiteness and lived experience in a racialized society.'

Published on April 18, 2016 15:14

Lincoln Center Offstage: Imani Uzuri Sings "I Love Myself When I'm Laughing"

'Composer and vocalist Imani Uzuri sings her song “I Love Myself When I’m Laughing…,” inspired by the words of Zora Neale Hurston, at Silvana, a cafe in Harlem.' -- Lincoln Center

'Composer and vocalist Imani Uzuri sings her song “I Love Myself When I’m Laughing…,” inspired by the words of Zora Neale Hurston, at Silvana, a cafe in Harlem.' -- Lincoln Center

Published on April 18, 2016 15:06

Rev. Dr. Eboni Marshall Turman: The Black Church on Black Lives Matter

On this episode of

Left of Black on The Root

, host Mark Anthony Neal sits down with Rev. Dr. Eboni Marshall Turman to talk about her strategies to provide spiritual guidance in the midst of an upsurge of Anti-Black Violence and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement. Dr. Rev. Marshall Turman directs Black Church Studies at the Duke University Divinity School; she joins the faculty at Yale Divinity School in the Fall.

On this episode of

Left of Black on The Root

, host Mark Anthony Neal sits down with Rev. Dr. Eboni Marshall Turman to talk about her strategies to provide spiritual guidance in the midst of an upsurge of Anti-Black Violence and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement. Dr. Rev. Marshall Turman directs Black Church Studies at the Duke University Divinity School; she joins the faculty at Yale Divinity School in the Fall.

Published on April 18, 2016 14:55

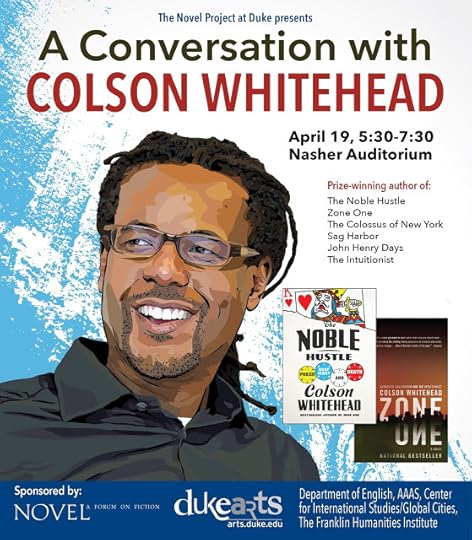

A Conversation with Colson Whitehead at The Nasher Museum on April 19, 2016

The Novel Project at Duke University in collaboration with the journal Novel: A Forum on Fiction, the Office of the Vice Provost for the Arts, the English Department, the Center for International Studies/Global Cities, and the Department of African-American Studies would like to invite you to “An Evening with Colson Whitehead.”

The Novel Project at Duke University in collaboration with the journal Novel: A Forum on Fiction, the Office of the Vice Provost for the Arts, the English Department, the Center for International Studies/Global Cities, and the Department of African-American Studies would like to invite you to “An Evening with Colson Whitehead.” On April 19th at the Nasher Museum Auditorium , award-winning novelist Colson Whitehead will speak about his latest work and the craft of fiction. Whitehead’s talk will begin at 5:30 PM to be followed by a Q&A with Duke Professors Mark Anthony Neal, Nancy Armstrong, and members of the audience.

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Whitehead is the author of seven books: The Intuitionist, nominated for the PEN/Hemingway Award; John Henry Days, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award; The Colossus of New York, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year; Apex Hides the Hurt, winner of the PEN/Oakland Award; Sag Harbor, a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award; Zone One, a New York Times bestseller; The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky & Death; and the forthcoming novel The Underground Railroad.

Published on April 18, 2016 09:41

April 17, 2016

From Flint to Ferguson: Reflections on African American Studies with Dr. Cathy J. Cohen

University of Chicago Political Scientist Cathy J. Cohen reflects on the field of African American Studies at Princeton University. Professor Cohen is introduced by Professor Eddie Glaude, Jr., Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton.

University of Chicago Political Scientist Cathy J. Cohen reflects on the field of African American Studies at Princeton University. Professor Cohen is introduced by Professor Eddie Glaude, Jr., Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton.

Published on April 17, 2016 20:52

The Wisdom of Duke Ellington + Chico Freeman's "Spook & Fade"

Published on April 17, 2016 12:32

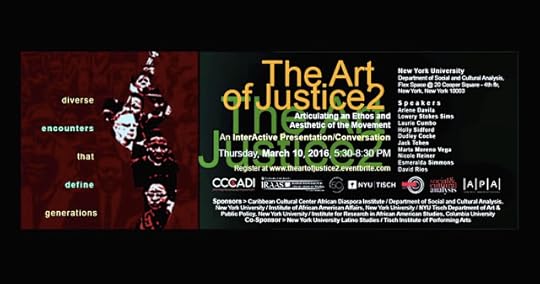

Race + Arts Funding + Survival of Community-Based Arts Organizations

'CCCADI co-presented The Art of Justice 2: Race, Arts Funding, and the Survival of Community-Based Arts Organizations, at NYU's Department of Social Analysis. It was a gathering of policymakers, researchers, scholars, and cultural activist to call for more equitable funding in the arts sector.' -- +CCCADI MEDIA

'CCCADI co-presented The Art of Justice 2: Race, Arts Funding, and the Survival of Community-Based Arts Organizations, at NYU's Department of Social Analysis. It was a gathering of policymakers, researchers, scholars, and cultural activist to call for more equitable funding in the arts sector.' -- +CCCADI MEDIA

Published on April 17, 2016 07:19

Douglas Rushkoff: Welcome to the Economy of 'Likes'

'Online businesses were originally measured by how much they sold. Makes sense, right? That's how economics is taught. But today, the largest online companies depend on an "economy of likes" to make money, says media theorist Douglas Rushkoff. Valuations for companies like Facebook depend largely on their user base, he says, rather than their actual profits. An interesting case in point is Jay-Z's partnership with Samsung. Rushkoff's latest book is Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity.' -- +Big Think

'Online businesses were originally measured by how much they sold. Makes sense, right? That's how economics is taught. But today, the largest online companies depend on an "economy of likes" to make money, says media theorist Douglas Rushkoff. Valuations for companies like Facebook depend largely on their user base, he says, rather than their actual profits. An interesting case in point is Jay-Z's partnership with Samsung. Rushkoff's latest book is Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity.' -- +Big Think

Published on April 17, 2016 07:06

April 16, 2016

Domesticating Genius: ‘Miles Ahead’ and the Challenge of Interiority by Mark Anthony Neal

Domesticating Genius: ‘Miles Ahead’ and the Challenge of Interiorityby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Domesticating Genius: ‘Miles Ahead’ and the Challenge of Interiorityby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Admittedly, Don Cheadle’s Miles Ahead offers a lingering glance -- a literal drive-by, if you consider the film’s now infamous car chase scene -- of one of the least known periods of Miles Davis’s life. As such, the film mines as much truth (as opposed to fact) as it does the mythology of a figure, who may be one of the most mythological Black men of the 20th Century; everyone has a story about what Miles did or said on-stage, with his back turned, to an audience of compliant White ticket buyers. As Cheadle admits, of this, his directorial debut, the film is “as much a composition as any of Miles’ recordings. It’s loose and impressionistic.”

Yet it is when the film dares to slow down -- and stops feeling like Lethal Weapon with a jazz score -- that we get to experience Davis in metaphoric repose, as the genius domesticated, and struggling with the freedom he demands for himself, but denies the woman whose own creative freedom is his inspiration. That is to say that so much of Miles Ahead is spent in the legendary West Side apartment of the trumpeter, where we initially find him alone wallowing in drug dependency and artistic exile, and in flashbacks, at the peak of his artistic power, under the care of his wife and dancer Frances Davis, portrayed by Emayatzy Corinealdi, who demands your attention in every scene she is in.

As Cheadle explains, the flashbacks with Francis Davis offer some insight into the trumpeter’s “writer’s block,” where “Frances represents his muse, the voice he has lost and is trying to recapture.” In one of the character’s intimate interactions early in the film, Frances describes to Miles what she experiences while dancing on stage -- a sense of “falling” -- which in the movement of the film immediately translates into Miles’s creation of “Fran-Dance.” This scene is important because here Frances is not just some idealized feminine muse, but someone, who in the intimacy of the domestic space, Miles could envision as a creative equal.

This pillow-talk discourse between two artists-as-lovers complicates, Hazel Carby’s well circulated readings of Miles Davis’s misogyny and physical abuse against his most intimate partners. As Carby writes in her book Race Men, “I think it is very important to challenge the apparent distance between Davis’s violence against women and the ‘genius’ of his music, as if they were enacted on different planes” (144). What Miles Ahead revisions, is not the reality of Miles’s violence -- the film makes explicitly clear Miles’s violence towards Frances -- but the extent that such abuse was more than the by-product of socially constructed gender expectations.

As Frances Davis herself recalls in a New York Times interview from a decade ago, Miles Davis believed that “A woman should be with her man,” yet in the intimacy of the domestic space as drawn by Cheadle’s Miles Ahead, we bear witness to Frances’s value to the artist Miles Davis, as it was her creativity and artistic sensibilities that ordered his domestic life, creating a productive space for both Miles’s creativity and his sense of masculine pride. As Corinealdi’s Frances pointedly tells Cheadle’s Miles -- when their relationship begins to fray -- “I make your life beautiful,” adding that “you’ve never sounded better.”

Miles Davis’s marriage to Frances Davis coincides with what is generally regarded as the artist’s most accomplished period, inclusive of the career defining Kind of Blue (1959) and concluding with the breakup of his “second” great quintet that featured Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams and Ron Carter. As was the case with Frances Davis, Miles Davis thrived in the intimacy of particularly strong Black women artists, including musician Betty Mabry Davis -- who emboldens Davis’s electric period -- and actress Cicely Tyson, who helps nurse Davis back to health when he re-emerges in the public eye in the early 1980s.

Again this is not to obscure the violence; Frances Davis recalls “running for my life — more than once,” a moment that Miles Ahead captures, and Miles Davis himself narrates his brutality towards Tyson (if uncritically) in his autobiography (written with Quincy Troupe), inspiring Pearl Cleage to pen the essay “Mad at Miles,” to give clear Black feminist language to Davis’s violence and the silence surrounding it. Davis’s penchant for intimate partner violence might reveal, in part, the frustration that he aligned with the absolute need for Black women as artistic partners and equals, the inability to acknowledge as much given the gender mores of the times, and his own investment in the idea of the singular Black Male Genius. In this regard Carby is dead-on when she argues that Miles Davis sought “freedom from a confinement associated with women, and freedom to escape to a world defined by the creativity of men” (138).

What Cheadle’s Miles Ahead makes plain is the extent that Miles Davis was dependent on the interiority of his art. As poet Elizabeth Alexander offers, the “The Black Interior is not an inscrutable zone, nor colonial fantasy. Rather, I see it as inner space in which black artists have found selves that go far, far beyond the limited expectations and definitions of what black is, isn’t or should be” (The Black Interior, 5).

Indeed Miles Davis’s literal balancing act in the film between his rehearsal studio in the basement of his apartment, and the domestic drama above in the “home” with Frances Davis, highlights how fraught his art was with tensions of domesticity. At its core Miles Ahead illuminates how Miles Davis never resolved the anxieties associated with his need for the domestic as a province for the Black female genius that inspired him, while privileging of public articulation of the singular Black male creative genius.

+++

Mark Anthony Neal is Professor of African + African-American Studies and Professor of English at Duke University, where he directs the Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship. He is the host of the video podcast Left of Black.

Published on April 16, 2016 16:53

April 15, 2016

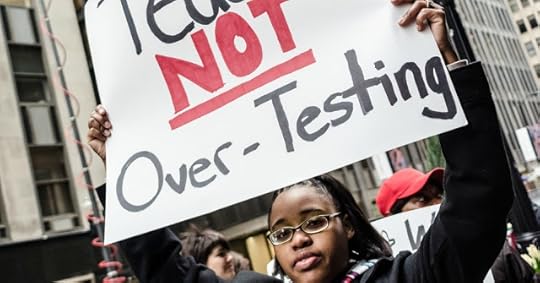

Hundreds of Baltimore Students Stage A Walkout Against Standardized Testing

'Days before the anniversary of the killing of Freddie Gray, students with the Baltimore Algebra Project walk out against the PARCC test to demand a shift in resources from testing to youth development.' +The Real News Network

'Days before the anniversary of the killing of Freddie Gray, students with the Baltimore Algebra Project walk out against the PARCC test to demand a shift in resources from testing to youth development.' +The Real News Network

Published on April 15, 2016 22:06

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.