“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workers

“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workersby Bianca Williams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

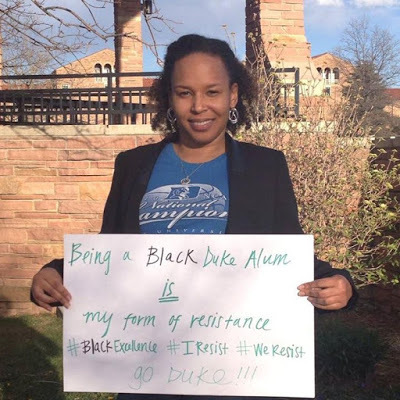

“Being a Black Duke Alum is a Form of Resistance”: A Note of Solidarity with Duke Students & Workersby Bianca Williams | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)A few days ago, FB let me know it has been a year since I posted the above pic. Taken after hearing from Black Duke undergrads that they found a noose hanging from a tree on campus, but before our 2015 men's basketball championship, I posted this message to be in solidarity with the students: "Yes, I taught [at CU Boulder] in my 2010 championship shirt today. Got lots of side-eye. Duke hate is real, but hilarious. Racism is real and terribly sad. Duke, I love you. But we gotta do better. So win the championship, and then let's get on that MANDATORY critical race and inequities class for students AND faculty. Being a BLACK Duke alum is my form of resistance."

As a former Duke student, and now as an alum, I am constantly aware that Du Bois' concept of “double-consciousness” and Crenshaw’s “intersectionality” are still relevant. That my love for an institution that provided me with an amazing education; a group of brilliant life-long friends; resources to dream big and think critically; a beautiful living and learning environment; generous and fierce mentors and advisors; and the experience of watching the best basketball teams in the country (both women’s and men’s, and always!), is deeply interwoven, and sometimes predicated, on my position as a second-class member of this community as a Black (including Caribbean!), first-generation college-educated woman.

My mind, body, and spirit recognized and felt the plantation politics of Duke before I had the words or analysis to comprehend the different aspects of it. I understood that in many ways Duke’s institutional and social culture was grounded on extracting, underpaying, and undervaluing the physical and emotional labor of thousands of its employees. I was hyper aware of my internal conflict and tension as I experienced the social capital and privilege bestowed on me as I matriculated into the Duke community. I remember the shock I felt when a professor told me that once I graduated from Duke, I would no longer be a part of the working-class community I still saw myself as an active member of, simply because of the economic and social capital of Duke’s name and my degree. To this day I tell my students that I’m “hesitantly middle-class, and learning every day what that means.”

At Duke, I sometimes found myself feeling more comfortable with the staff at the Marketplace or in the dorms than fellow students or professors, because they reminded me of my mom, my aunties, my cousins, and where I came from. When I felt invisible, they saw me. It was the workers in Bassett who would stop me when I clearly had a bad day on campus, and would chat with me to lift my spirits. It was these workers who made sure I was okay when I couldn’t afford to go home on breaks. It was the workers in the East Campus store, and those that chilled with me on the Black bench during their breaks, who greeted me BY NAME. They STILL do whenever I return to campus and see some of them around the community. It was the Black women workers who empathized with me when I would pull all-nighters in the Friedl building, studying for preliminary exams and writing my dissertation during graduate school.

In fact in 2009, when I spent weeks ferociously writing from 10 pm to 6 am to finish my dissertation, it was these women who came to clean the building in the morning who would send me home as the sun came up. They would admonish me for not getting sufficient rest, while giving me pep talks about how I was going to finish and stating that they were proud of me. The day I pressed the “send” button and submitted my dissertation to my advisor, it was these women who knew first, and celebrated with me through my exhaustion and delirium.

Again, they let me know that I wasn’t invisible and that they saw me. And I saw them. I wouldn’t pass by without saying hello or giving a head nod. The Duke culture that taught me that somehow I was supposed to be better than them; that their humanity and their labor was supposed to be invisible; that our struggles in a deeply racialized and economically-oppressive space were not intertwined, was not acceptable to me. And my mom’s home-training wouldn’t allow me to ignore these things or these individuals who were a significant part of the Duke community.

I remember the exhaustion and frustration as I spent more hours in meetings with peers and administrators, resisting and protesting structures and a culture that was oppressive to the ENTIRE community, than in the classroom. I remember the sting of shame and isolation when I opened my school’s newspaper after Spring Break to find a full-page ad declaring that reparations for slavery are wrong and racist, and welfare was a form of “paying” African Americans reparations. I remember the apologetic, knowing looks I would give Black staff when students of all races treated them like “the help” in the cafeteria, on the bus, and on the quad. I remember the fear as I walked by benches of drunk, white fraternity men screaming (or whispering) racial epithets, simultaneously declaring their love for hip-hop, while sending leery glares over my Black feminine body.

I remember the anger burning in my belly when I knew that Black workers were going to have to clean up their trash and vomited mess in the morning. I remember being grateful as I sat on the Black bench and learned from a worker about the Duke plantation—plantation politics—for the first time, understanding there was a name for what I was experiencing and seeing. Duke, the institution and the community, taught me about racism and economic inequity both inside and outside the classroom, and Duke’s workers were a significant part of that education. I never forget those Black workers and students who made it possible for me to make it through to the other side.

This is why I send my full love and support to the students occupying the Allen Building, and the supporting workers and students in Abele-ville. My organizing energy goes to those students and workers demanding that the most vulnerable in our community get the resources they need and have earned. My “that’s right, say it again!” energy goes to those students that demand that all members of Duke’s community (especially well-paid and powerful administrators) are held to the standards and values that will eventually make Duke the amazing place it aspires to be. You all are doing remarkable and necessary work not only in the Duke community, but also in the nationwide community that is U.S. higher education. We are watching. We are learning. And you are teaching.

I am a member of Duke’s community. I am Forever Duke. I earned that right, and it is a lifelong membership. But know that being a Black Duke alum is a form of resistance for me. And as a member of Duke’s community, I feel it is my duty to love Duke in the Baldwinian-sense: to make you aware of the things you don’t see, and to perpetually critique you until you do better. Duke, you can try to wait this out if you want, but know that these students, and the Movement for Black Lives many of them are learning from, ain’t going anywhere.

***

Bianca Williams is Assistant Professor on Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is the author of the forthcoming Exporting Happiness (Duke University Press).

Published on April 08, 2016 16:36

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.