Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 518

May 13, 2017

Esperanza Spalding Conjures Abbey Lincoln’s Insurgent Moans by Tanisha C. Ford

Esperanza Spalding Conjures Abbey Lincoln’s Insurgent Moans by Tanisha C. Ford | @SoulistaPhD | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Esperanza Spalding Conjures Abbey Lincoln’s Insurgent Moans by Tanisha C. Ford | @SoulistaPhD | NewBlackMan (in Exile)When three multiple Grammy award-winning jazz vocalists unite on one stage for a concert conceived and directed by a genius black woman drummer/composer to pay homage to one of the best to ever do it, magic will be made.

I recently attended the Apollo Theater’s Women of the World Festival: A Tribute to Abbey Lincoln. Vocalist and bassist Esperanza Spalding performed alongside jazz luminaries Dianne Reeves and Dee Dee Bridgewater. Musical director, drummer Terri Lyne Carrington—the visionary behind this assemblage of black creative genius—fearlessly lead a six-piece band on a 120-minute journey through Lincoln’s catalogue. My longtime favorites Reeves and Bridgewater sang their faces off, stirring our spirits with each note, even using Lincoln’s garments (her scarf and signature top hat) to invoke her spirit.

But I wondered: could Spalding—who, unlike the others, wasn’t even born when Lincoln released much of her music—hold her own as a soloist among these powerhouse vocalists? I mean, I knew Esperanza could sing, but could she sang? I thought of her primarily as a virtuosic bassist. But here she was, sans bass, standing next to some of the greatest living jazz vocalists, attempting to sing Lincoln’s deeply emotional, sonically complex songs.

Music critics have described Spalding’s vocals as “light” and “high,” “delicate” like the sounds of a violin. But she proved to me—and anyone else who had doubts—that she also has a deeper, darker sonic register. She did more than hold her own. Spalding painted with cocoa hues and effervescent blues as she scatted, screeched, yipped, and moaned “Afro Blue,” a mainstay in Lincoln’s repertoire. Trenchant in her delivery, she conjured Abbey Lincoln, performing the same sounds that got Lincoln virtually blackballed by the music industry after the release of jazz drummer Max Roach’s now classic We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite (1960). Hers were insurgent moans—sounds of protest.

Spalding had to go there.

A vocalist cannot pay homage to Abbey Lincoln unless she is willing to access the vulnerable place. She must reach into the deepest caverns of her gut to wrench out her rawest emotions and expose them to the audience. Those emotions do not always take shape in words.

Lincoln knew this better than anyone.

More than five decades ago, Abbey Lincoln introduced jazz audiences to her rebel sounds on We Insist!. Both cerebral and sensorial, the five-track album was a work of musical innovation, now considered one of the first overtly political albums of the Black Freedom movement. The only woman involved in the writing and composing (though she is only listed as a vocalist in the album’s credits), Lincoln uses her voice as both instrument and siren on “Freedom Day” and “Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace” to communicate the political urgency of the moment. Black rage, pain, despair, and hope are made palpable through Lincoln’s quiet hums and moans, which crescendo into screams, screeches, and chants. Crescendo. Decrescendo. Her guttural sounds are intense and impatient, insistent, demanding: FREEDOM NOW.

White music critics did not understand the highly conceptual, genre-bending album. Shortly after its release, Washington Post music writer Tony Gieske claimed: “the music really isn’t too hot.” He panned Lincoln’s performance, saying, “Abbey Lincoln, uh, sings.” The harsh mainstream reviews and meager sales of We Insist! stifled Lincoln’s music career just as it was beginning to flourish. She was “too political,” her music “too radical.” In other words, she was pushing the boundaries of innovation while naming anti-black racism in ways unpermitted to black women. The industry was quick to remind her of “her place.” Lincoln recorded a politically themed solo album, Straight Ahead (1961), the following year, but more than a decade would pass before she released People in Me (recorded in Japan) in 1973.

For the black student activists across the U.S. South who inspired We Insist!, Lincoln’s insurgent moans were political action in sonic form. Music and activism shared a common language, and Lincoln, a seasoned activist, had a profound understanding of both.

That Spalding (who sings in three languages) could understand and speak Lincoln’s political tongue comes as no surprise to those familiar with her catalogue. Much of Spalding’s music, including “We Are America,” “Black Gold,” and “Ebony and Ivy,” explores political themes. On her new album, Emily’s D+Evolution—undoubtedly a response to today’s political climate—Spalding takes huge creative risks, crushing the box in which critics have placed her. We hear her borrowing from and remixing the sounds and musical techniques of everyone from Joni Mitchell and Prince to Nina Simone and Abbey Lincoln. Lincoln’s spirit of protest is in Spalding’s musical DNA.

But, more than a descendant of Lincoln, that night at the Apollo Spalding was the conduit through which Lincoln’s political fervor from the 1960s was rendered anew. And my battle-torn and weary spirit needed it.

+++Tanisha C. Ford is Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History at the University of Delaware. She is the author of Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (UNC Press, 2015). Follow her on twitter @SoulistaPhD.

Published on May 13, 2017 06:54

May 12, 2017

Sacrifice A Whole Lot: Memphis and Marco Pavé

Sacrifice A Whole Lot: Memphis and Marco Pavéby Charles L. Hughes | @CharlesLHughes2 | NewBlackMan (in exile)

Sacrifice A Whole Lot: Memphis and Marco Pavéby Charles L. Hughes | @CharlesLHughes2 | NewBlackMan (in exile)The story of Memphis music – like that of the city itself – is the story of Black accomplishment despite white violence. As the enslaved and emancipated came to the city in droves in the 1800s, they brought religious and social songs with them that chronicled the desires of the community and bound it together in the midst of massacres and betrayals. At the turn of the century, when Jim Crow and lynching tightened its deadly grip, W.C. Handy and others innovated modern sounds that sounded the call of Black genius. Beale Street’s heyday in the 1920s and 1930s gave Memphis an international cultural reputation for blues and jazz even as it reflected the oppression of its creators and audiences.

The restless rhythms of Sun Records rock ‘n’ roll signaled both the possibilities and limitations of desegregation at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement. Soul music from Stax and elsewhere offered celebratory demands that amplified the calls of the Civil Rights and Black Power era. Memphis hip-hop reckoned with that era’s success and failures in the context of structural disinvestment and new waves of incarceration and surveillance. To this day, Memphis musicians define a city that is haunted by its past, struggling with its present, and unsure of its future.

It is into this conversation that Marco Pavé enters with his stunning debut album, Welcome to Grc Lnd. Standing at the crossroads of funk futurism and blues fatalism, the young hip-hop artist and activist has created a rich sonic geography of his home that forces listeners to reckon with what he calls “the city that they don’t let show.”

Pavé’s tracks lay in the cut of the everyday experiences of young, working-class Black Memphians. The ones who face the greatest disadvantages in education, health, economics and the criminal-justice system. The ones dismissed by whitesplained claims of “black-on-black crime” or demonized by lies about their supposed dysfunction. The ones who don’t get figured in to romanticized celebrations of Memphis’s musical legacy or contemporary efforts to build the city’s musical economy. The ones who, as ever, are in danger of being left out as the city moves into a “revitalized” 21st century. And the ones who – just like early generations – are surviving, resisting, working, creating and building nonetheless.

On this loving and raucous record, Pavé – a proud son of North Memphis – tells their stories. A righteous and revolutionary dance party, Welcome to Grc Lnd announces the arrival of a major artist and shines a spotlight on the community that surrounds him. It’s one of the best albums to emerge from Memphis in some time, and one of the best albums about Memphis that I’ve ever heard.

As he says at one point, “I’m so Memphis they can’t fuck with it.” Musically, this means drawing on the city’s hip-hop from Gangsta Pat to Gangsta Boo and incorporating soul horns, blues guitar, gospel vocals, and other sounds of Memphis. (As opposed to the frozen-in-amber “Memphis sound” that continues to limit perceptions about the city’s musical identity.) He also offers a full-throated declaration of love for the city and its marginalized citizens. He addresses historical traumas; the King assassination, of course, but also less famous disasters like the massive job-loss of the 1970s and beyond. He signifies on local heroes from Ida B. Wells to Zach “Z-Bo” Randolph. He rejects attempts to gloss over the ongoing nightmare of white supremacy through vague calls for “racial healing,”

And, refreshingly, Pavé critiques the easy sloganeering of “grit and grind,” which has been appropriated from working-class Black communities and turned into a ubiquitous motto of the city’s supposedly shared identity. Through crisp and bluesy verses, Pavé chronicles his community’s survival and renewal in the face of systemic discrimination and okey-doke posturing. The hook on “Home” is only the bluntest version of the album’s central motif: “I just want to be home, even though I know that’s where the hate is.”

This seemingly-paradoxical thesis finds its metaphor in the title image, invoked by award-winning local author Jamey Hatley in spoken segments that appear several times on the record. Over a shimmering Isaac Hayes sample, Hatley presents Graceland as the centerpiece of a key Memphis myth – a monument to the white past that collides with the realities of the Black present. Elvis Presley’s home is the city’s most famous landmark, a profitable tourist attraction, and a cornerstone to its civic narrative as a musical capital of the world.

But Graceland also symbolizes how that narrative contradicts the experiences of too many of its citizens. (In Hatley’s words: “Welcome to Graceland, the home of ‘grit and grind’ – even though some get ground…never mind that, welcome to Graceland.”) Paul Simon used it as a symbol for (white) redemption in his acclaimed 1987 song, and Marc Cohn made it part of his personal pilgrimage to heal his broken heart in the famed hit “Walking in Memphis,” which has been used in advertisements for Memphis tourism. But, for Hatley and Pavé, Graceland reflects a deep and open wound. As Pavé told Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib in a brilliant essay at MTV.com, he spells it without vowels “because the Grace is broken.”

This was particularly visible in August 2016, when Graceland was the site of a #BlackLivesMatter protest that ended with the violent arrest of several protesters. Organizers chose Graceland – and the timing of the “Elvis Week” celebration that brings thousands of fans to Memphis – to spotlight this very disjunction; they were subsequently pilloried in the media as unreasonable disruptors. Accordingly, this story becomes a key touchstone for Pavé. Here, as elsewhere, he passes the mic, as activist Dana Asbury tells her story. In chilling detail, Asbury recounts her assault by police and mistreatment by medical personnel. She describes one paramedic accosting her during the ride to the hospital: “Don’t you know Elvis fans don’t come here to hear about your issues? They care about Elvis.”

The protest was part of a longer response to the police killing of the unarmed Darrius Stewart in 2015 and the subsequent lack of action by Memphis law enforcement. Stewart’s ghost haunts Welcome to Grc Lnd as much as Dr. King or “The King,” but he is invoked explicitly only at the end by activist Keedran “TNT” Franklin. Here, Franklin tells the story of the public activism of Stewart’s mother, whose protests landed her on an official “blacklist” of people forbidden to enter Memphis City Hall.

This choice to end with the testimony of Darrius Stewart’s mother is fitting, since Welcome to Grc Lnd is defined as much by the voices of Black women as by Marco Pavé himself. He features guest musicians like Dutchess (who contributes one of the album’s best verses) and Big Baby (whose vocals electrify the Goodie Mob gospel of “Let Me Go”). And he extends this call-and-response to Hatley, acclaimed sociologist/cultural critic Zandria F. Robinson (whose backing vocals add a surreptitious citation of her brilliant book This Ain’t Chicago) and community organizers Asbury, Jayanni Elizabeth, and Idealy Maceano.

Indeed, while the album’s sonic genealogy stretches from Curtis Mayfield to Big K.R.I.T., Welcome to Grc Lnd has no greater influence than Anna Julia Cooper, Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer and other southern Black women who’ve raised their voices against centuries of injustice. Pavé has discussed his decision to pass the mic to these artists, scholars and freedom fighters as an intentional enactment of intersectional politics and a reminder of the centrality of women to the cultural and political traditions of Memphis and the South. It’s also a tribute to the tradition of testimony – against violence and towards freedom – that has shaped the political work of Black women from slavery to the present. As Asbury recalls, referring to her mistreatment in a Memphis hospital, “they pushed me into another room, and I started speaking.”

On Welcome to Grc Lnd, the music speaks as loudly as the lyrics. The burden is ever-present, in the battering backbeats and brooding moans that underlay tracks like “Gun Barrel” or “Hold Us Down.” But so is resistance, with the echoing waves of “This Little Light Of Mine” that wash in at the end of “Hood Obit,” or the haunting freedom-song chorus of “Neva Stop It.” At the crux of these legacies, and at the core of these propulsive tracks, is the will to survive, a theme that Pavé returns to throughout the album. On the thunderous “Sacrifice,” for example, he insists that he’s sacrificed “a whole lot” to get where he is, and that he deserves a gold watch so that “my time ain’t gonna ever stop.” Simultaneously brash and vulnerable, Pavé makes a claim for the future as powerfully as he asserts his right to exist in the present.

This demand permeates and fuels Welcome to Grc Lnd, a crucial new chapter in the city’s long and celebrated musical history. “If Memphis is looking for the next incarnation of its musical identity,” Rodney Carmichael correctly noted at NPR.org, “this is it.” On this brilliant album, Marco Pavé seeks reckoning before reconciliation and demands justice as a necessary precondition for peace. These booming bars find Marco Pavé and his collaborators dive into the deep, muddy water of the Mississippi River and call forth Memphis’ legacies of resistance and rebirth. Let’s honor their work by turning it all the way up and making everybody listen.

Welcome to Grc Lnd is available to purchase here.

***

Charles L. Hughes is Director of the Memphis Center at Rhodes College. His book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, is now available from the University of North Carolina Press. Follow him on Twitter @CharlesLHughes2.

Published on May 12, 2017 06:46

May 11, 2017

Left of Black S7:E24: Environmental Justice + Sustainability + Political Pragmatism in the Black Belt

Left of Black S7:E24: Environmental Justice + Sustainability + Political Pragmatism in the Black Belt

Left of Black S7:E24: Environmental Justice + Sustainability + Political Pragmatism in the Black BeltOn this episode of Left of Black, activist Catherine Coleman Flowers, joins host Mark Anthony Neal in studio to discuss environmental justice in Lowndes County, Alabama, including her working relationship with former Alabama Senator and current US Attorney General, Jefferson Sessions. Coleman Flowers is Director of Environmental Justice and Civic Engagement of the Center for Earth Ethics at Union Theological Seminary and founder of the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise Community Development Corporation (ACRE). Coleman Flowers is the 2017 Franklin Humanities Institute Practitioner in Residence.

Left of Black is hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced by Catherine Angst of the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in collaboration with the Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) and the Duke Council on Race + Ethnicity (DCORE).

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on May 11, 2017 04:59

May 10, 2017

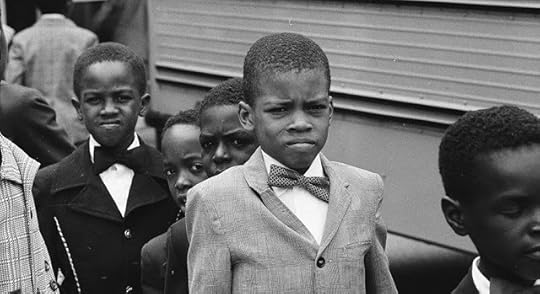

A Brief Visual History of Black Muslims in Chicago

'During the 1960s, in the midst of the civil rights movement against segregation and discrimination, the teachings of the Nation of Islam extended beyond the fight for equality to include racial self-reliance, discipline, and economic independence. Chicago Reader looks back at Chicago’s Black Muslim community during the 1960s and 1970s, observing a variety of practices the Nation of Islam encouraged in its followers’ journey of spiritual growth and self-sufficiency.'

'During the 1960s, in the midst of the civil rights movement against segregation and discrimination, the teachings of the Nation of Islam extended beyond the fight for equality to include racial self-reliance, discipline, and economic independence. Chicago Reader looks back at Chicago’s Black Muslim community during the 1960s and 1970s, observing a variety of practices the Nation of Islam encouraged in its followers’ journey of spiritual growth and self-sufficiency.'

Published on May 10, 2017 15:57

Nile Rodgers and "The Unbearable Whiteness of Indie"

'In this podcast, Duke University student Conor Smith ('17) examines the Indie music scene, "Columbus-ing" and the legacy of Nile Rodgers; This podcast is the product of an Independent Study at Duke University, under the advisement of Mark Anthony Neal.'

'In this podcast, Duke University student Conor Smith ('17) examines the Indie music scene, "Columbus-ing" and the legacy of Nile Rodgers; This podcast is the product of an Independent Study at Duke University, under the advisement of Mark Anthony Neal.'

Published on May 10, 2017 15:48

NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism: on Black Women and Virtual Reality

'NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism is an art installation and virtual reality experience recently featured at the Tribeca Film Festival. The project, which seeks to put women of color in the virtual reality space, was created by Hyphen Labs, a collective of women from diverse backgrounds.' -- +The Root

'NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism is an art installation and virtual reality experience recently featured at the Tribeca Film Festival. The project, which seeks to put women of color in the virtual reality space, was created by Hyphen Labs, a collective of women from diverse backgrounds.' -- +The Root

Published on May 10, 2017 15:39

Nas Deconstructs "It Ain't Hard to Tell" with Harvard Professor Elisa New

In this clip from Poetry in America, Harvard Professor Elisa New talks with Nasir "Nas" Jones about his song "It Ain't Hard to Tell."

In this clip from Poetry in America, Harvard Professor Elisa New talks with Nasir "Nas" Jones about his song "It Ain't Hard to Tell."

Published on May 10, 2017 15:27

Women + Media +Politics: A Conversation with Michel Martin + Farai Chideya + Rebecca Traister

'The 2017 Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture: "The New Normal? Women, Media, & Politics: A Conversation with Media Experts." Michel Martin, journalist and weekend host of NPR's All Things Considered moderated a conversation with Rebecca Traister, writer-at-large for New York Magazine and author of the New York Times best-seller, All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation; and Farai Chideya, reporter, political analyst, and fellow at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.'-- IWL Rutgers

'The 2017 Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture: "The New Normal? Women, Media, & Politics: A Conversation with Media Experts." Michel Martin, journalist and weekend host of NPR's All Things Considered moderated a conversation with Rebecca Traister, writer-at-large for New York Magazine and author of the New York Times best-seller, All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation; and Farai Chideya, reporter, political analyst, and fellow at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.'-- IWL Rutgers

Published on May 10, 2017 15:19

May 9, 2017

Visuals + Music: Jamila Woods --"Holy" (dir. Sam Bailey)

Published on May 09, 2017 06:35

May 8, 2017

How Inequality Can Be Fatal

'David Ansell, senior vice president and associate provost for Center for Community Health Equity, and the Michael E. Kelly Professor of Medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, joins us to discuss his new book,

The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills

. Ansell argues that where you live and how much you make can shorten your life expectancy. He draws on his experiences working at the hospitals of some of the poorest communities in Chicago, but also makes the case that this is a nationwide problem.' --

The Leonard Lopate Show

'David Ansell, senior vice president and associate provost for Center for Community Health Equity, and the Michael E. Kelly Professor of Medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, joins us to discuss his new book,

The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills

. Ansell argues that where you live and how much you make can shorten your life expectancy. He draws on his experiences working at the hospitals of some of the poorest communities in Chicago, but also makes the case that this is a nationwide problem.' --

The Leonard Lopate Show

Published on May 08, 2017 20:14

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.