Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 521

April 27, 2017

Dental Care is America's Most and Least Visible Healthcare Problem

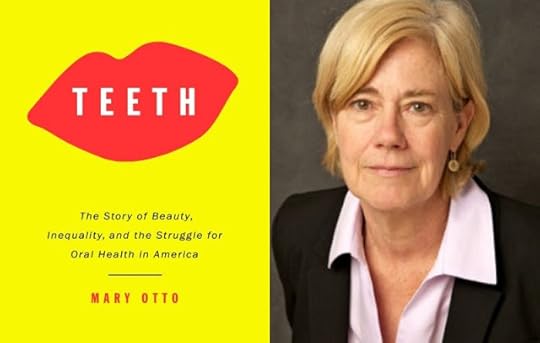

'Journalist Mary Otto examines the state of oral healthcare in America - from the roots of dental care's separation from medical insurance coverage, to an industry-wide shift away from care and prevention, and towards cosmetic procedures -- and finds the country's worsening class division and economic inequality present in even the mouths of its citizens. Otto is author of

Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America

from The New Press.' --

This Is Hell! Radio

'Journalist Mary Otto examines the state of oral healthcare in America - from the roots of dental care's separation from medical insurance coverage, to an industry-wide shift away from care and prevention, and towards cosmetic procedures -- and finds the country's worsening class division and economic inequality present in even the mouths of its citizens. Otto is author of

Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America

from The New Press.' --

This Is Hell! Radio

Published on April 27, 2017 03:44

How I Got Over: Lynn Nottage, Kate Whoriskey and 'Sweat' on Broadway

'With humor and heart Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play,

Sweat

, tells the story of a group of friends who have spent their lives sharing drinks, secrets and laughs while working together on the line of a factory floor. But when layoffs and picket lines begin to chip away at their trust, the friends find themselves pitted against each other in the hard fight to stay afloat. Kate Whoriskey directs this new play about the collision of race, class, family and friendship, and the tragic, unintended costs of community without opportunity. WNYC editor Rebecca Carroll sits down for an unconventional conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and acclaimed director.' --

The Greene Space

'With humor and heart Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play,

Sweat

, tells the story of a group of friends who have spent their lives sharing drinks, secrets and laughs while working together on the line of a factory floor. But when layoffs and picket lines begin to chip away at their trust, the friends find themselves pitted against each other in the hard fight to stay afloat. Kate Whoriskey directs this new play about the collision of race, class, family and friendship, and the tragic, unintended costs of community without opportunity. WNYC editor Rebecca Carroll sits down for an unconventional conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and acclaimed director.' --

The Greene Space

Published on April 27, 2017 03:28

There Is No 'Get Rich Quick Scheme' for Artists

'Performer Okwui Okpokwasili has a hard time calling herself an "artist" sometimes, but she's managed to make a living as one in New York City for a few years. Okpokwasili said it's getting harder to make it in New York City as an artist, especially without a trust-fund or a patron, but the city isn't dead for the arts. "People always find a way," she said.' -- WNYC

'Performer Okwui Okpokwasili has a hard time calling herself an "artist" sometimes, but she's managed to make a living as one in New York City for a few years. Okpokwasili said it's getting harder to make it in New York City as an artist, especially without a trust-fund or a patron, but the city isn't dead for the arts. "People always find a way," she said.' -- WNYC

Published on April 27, 2017 03:20

April 22, 2017

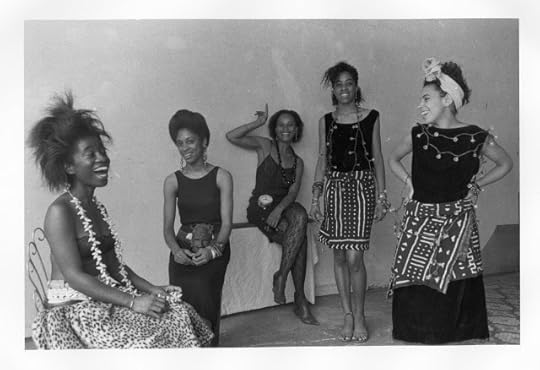

BK Live: "We Wanted A Revolution" Focuses on Black Radical Feminists Over the Years

'Focusing on the work of black women artists, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 examines the political, social, cultural, and aesthetic priorities of women of color during the emergence of second-wave feminism. Curated by Rujeko Hockley, it is the first exhibition to highlight the voices and experiences of women of color—distinct from the primarily white, middle-class mainstream feminist movement—in order to reorient conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history in this significant historical period.' --

BRIC TV

\

'Focusing on the work of black women artists, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 examines the political, social, cultural, and aesthetic priorities of women of color during the emergence of second-wave feminism. Curated by Rujeko Hockley, it is the first exhibition to highlight the voices and experiences of women of color—distinct from the primarily white, middle-class mainstream feminist movement—in order to reorient conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history in this significant historical period.' --

BRIC TV

\

Published on April 22, 2017 22:15

Adam Mansbach: Donald Trump -- The World's First TV President

'Until now, the relationship of the President of the United States to the TV had been predictable. The President made news, and satirists made fun of the President. The President did not watch the satirists because he had, um, more important things to do. Well, life comes at you fast. Today, perhaps the most reliable way to communicate with the President is to appear on a cable news show. The poor quality of these programs — especially their habit of featuring unqualified opinion in the interest of balanced reporting — has made maintaining an informed national conversation very difficult. And that was before the President was citing Joe Schmucko from Illinois! Adam Mansbach's most recent book (co-authored with Dave Barry and Alan Zweibel) is For This We Left Egypt?.' --

Big Think

'Until now, the relationship of the President of the United States to the TV had been predictable. The President made news, and satirists made fun of the President. The President did not watch the satirists because he had, um, more important things to do. Well, life comes at you fast. Today, perhaps the most reliable way to communicate with the President is to appear on a cable news show. The poor quality of these programs — especially their habit of featuring unqualified opinion in the interest of balanced reporting — has made maintaining an informed national conversation very difficult. And that was before the President was citing Joe Schmucko from Illinois! Adam Mansbach's most recent book (co-authored with Dave Barry and Alan Zweibel) is For This We Left Egypt?.' --

Big Think

Published on April 22, 2017 21:54

Studio 360: Black Cosplay

'Cosplay has gotten huge in the age of social media, but when websites feature photos and video from ComicCon, they often don't reflect the true diversity of the fans on the convention floor. Cosplayers Suqi Yomi and Brittnay N. Williams of the site Black Nerd Problems talk about the challenge of convincing other cosplayers that they can be whichever superhero they chose — not just the black characters. Harry Crosland and his wife Gina talk about why they like putting original spins on classic characters, and why the need to call out non-black cosplayers who don't understand that blackface shouldn't be part of any costume.' --

Studio 360

'Cosplay has gotten huge in the age of social media, but when websites feature photos and video from ComicCon, they often don't reflect the true diversity of the fans on the convention floor. Cosplayers Suqi Yomi and Brittnay N. Williams of the site Black Nerd Problems talk about the challenge of convincing other cosplayers that they can be whichever superhero they chose — not just the black characters. Harry Crosland and his wife Gina talk about why they like putting original spins on classic characters, and why the need to call out non-black cosplayers who don't understand that blackface shouldn't be part of any costume.' --

Studio 360

Published on April 22, 2017 21:36

Henry Giroux: "Trump is the Endpoint" -- On Cruelty and Isolation in American Politics

'Cultural critic Henry Giroux examines the slow, steady rise of cruelty in American culture -- as the logic of neoliberalism strips our politics of anything besides self-regard, and the right capitalizes on the anger caused by its own policies -- and calls for the left to reclaim a language of liberation, and then get out on the streets and start fighting the war it's been losing for decades. Giroux wrote the article "The Culture of Cruelty in Trump's America" for Truthout.' --

This Is Hell! Radio

'Cultural critic Henry Giroux examines the slow, steady rise of cruelty in American culture -- as the logic of neoliberalism strips our politics of anything besides self-regard, and the right capitalizes on the anger caused by its own policies -- and calls for the left to reclaim a language of liberation, and then get out on the streets and start fighting the war it's been losing for decades. Giroux wrote the article "The Culture of Cruelty in Trump's America" for Truthout.' --

This Is Hell! Radio

Published on April 22, 2017 21:21

April 21, 2017

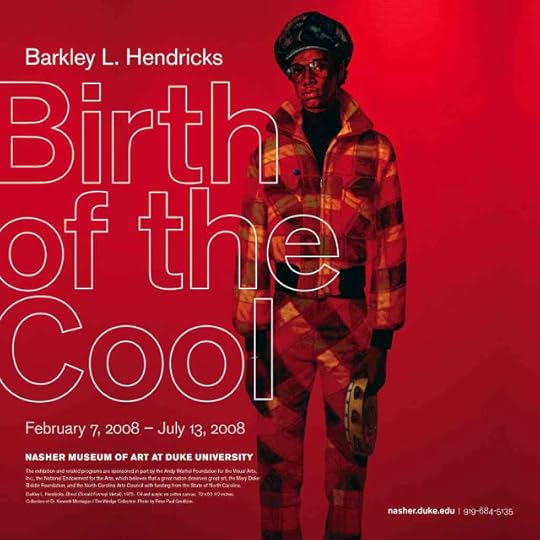

Critical Noir: Opening Barkley -- Review of 'Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of Cool" (2008)

Critical Noir: Opening Barkley (2008)by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Critical Noir: Opening Barkley (2008)by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Birth of Cool, a retrospective exhibition on the life and work of artist Barkley L. Hendricks opened at the Nasher Museum of Art in Durham, North Carolina. Conceived by Trevor Schoonmaker, the Curator of Contemporary Art at the Nasher Museum and Richard J. Powell, the John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art and Art History at Duke University, Birth of Cool is the first such retrospective of the Philadelphia native’s work.

According to Powell, the foremost scholar on Hendricks’s work, the idea of a Hendricks retrospective was “beguiling, with the idea to encounter old friends, audacious strangers, and engrossing paintings, it seems, for the very first time.” The exhibition’s opening night was reflective of Powell’s observations bringing together an eclectic group of people for a discussion between Hendricks and Powell, which was followed by an after-party that featured Grammy-award winning producer and DJ 9th Wonder.

Trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts and Yale University, Hendricks emerges in the late 1960s just as “Black Power” became synonymous with black vernacular culture via the agitprop of Black Arts Movement figures like Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal. Hendricks was primarily interested in figurative and life sized portraiture, thus his subjects, more often than not, were simply the bodies of everyday black folk. Hendricks’s aesthetic commitment to the “folk” likely helped keep him beyond the radar of the mainstream art world.

As Franklin Sirmans, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Menil Collection in Houston, “these are black people who are rarely glimpsed outside their community (not art galleries), but within these communities they can easily be seen just as easily as symbols of vibrant everyday life.” As such, over the past few decades, Hendricks has helped establish black bodies as sites vernacular culture—his influence seen in the work of younger artists such as Kehinde Wiley and even Iona Rozeal Brown

In the spirit of the iconoclasm that marks the work of Hendricks, he chose not to play to the visual politics of the late 1960s and early 1970s that demanded that black artists choose between the aesthetics of black rage and those defined of black middle-class uplift, even as both impulses pivoted on some notion of Black pride.

Powell writes in Birth of Cool (Duke University Press), the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, that Hendricks was “Neither content with an Ebony Magazine-styled black man and woman whose dress-for-success look approximated the corporate mainstream, nor completely at ease with the Afro-centric vogue of black cultural nationalism.” Hendricks’s choices, in this regard, seemed more attuned to the “queerness”—broadly defined here as that which pushed the boundaries of mainstream visual blackness—of his subject matters.

It was perhaps this “queerness” that attracted exhibition curator Trevor Schoonmaker to Hendricks’s work. According to Schoonmaker he found Hendricks as a subject compelling, much the way he found another iconoclast of Hendricks’s generation, compelling.

In Barkley L. Hendricks and the late Nigerian musician and activist Fela Kuti, Schoonmaker, who curated the Fela Kuti exhibition “Black President”, found two men who were “stanchly independent, rugged individualists who followed their respective visions to create innovative new artistic expressions, despite lack of commercial success.” Schoonmaker adds, Fela and Hendricks “called attention to and even championed people in society who had been underserved and otherwise rendered invisible.”

Published on April 21, 2017 10:57

April 20, 2017

'Jazz Is The Mother Of Hip-Hop': How Sampling Connects Genres

'Why do hip-hop producers gravitate toward jazz samples? For a mood, for sonic timbre, for a unique rhythmic component. Swing is a precursor to the boom-bap. "If you're a hip-hop producer that wants a lot of melodic stuff happening," pianist

Robert Glasper

says, "you're probably going to go to jazz first." In this short doc, Glasper identifies three jazz samples, from tracks by

Ahmad Jamal

and

Herbie Hancock

, that have served as source material for famed hip-hop producers

J Dilla

and

Pete Rock

.' -- +NPR

'Why do hip-hop producers gravitate toward jazz samples? For a mood, for sonic timbre, for a unique rhythmic component. Swing is a precursor to the boom-bap. "If you're a hip-hop producer that wants a lot of melodic stuff happening," pianist

Robert Glasper

says, "you're probably going to go to jazz first." In this short doc, Glasper identifies three jazz samples, from tracks by

Ahmad Jamal

and

Herbie Hancock

, that have served as source material for famed hip-hop producers

J Dilla

and

Pete Rock

.' -- +NPR

Published on April 20, 2017 08:50

Left of Black S7:E22: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation

Left of Black S7:E22: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation

Left of Black S7:E22: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison ProliferationOn this episode of Left of Black, Sociologist John M. Eason joins host Mark Anthony Neal in the Left of Black studio at the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University to discuss his book Big House on the Prairie: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation (University of Chicago Press).

Eason is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Texas A&M University. Of Professor Eason’s Big House on the Prairie, noted sociologist Mary Pattillo writes, “Big House on the Prairie is a masterful, sensitive, and theoretically complex study of the politics of prison building in a southern town dealing with the ‘quadruple stigma of rurality, race, region, and poverty.’” Left of Black is hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced by Catherine Angst of the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in collaboration with the Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) and the Duke Council on Race + Ethnicity (DCORE).

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on April 20, 2017 08:09

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.