Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 411

January 19, 2019

Sex is Complicated, Work is Bad: On the Politics of Sex Work Under Capitalism

'Writer and sex worker Molly Smith explores the politics of sex work - from the realities of a job on the precarious edges of capitalism, misogyny and the carceral state, to sex work's contested place within both feminism and social movements at large - and explains why sex workers, like all workers, need solidarity and liberation, not cops and punishment. Smith is co-author of the new book

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights

from Verso.' --

This is Hell! Radio

'Writer and sex worker Molly Smith explores the politics of sex work - from the realities of a job on the precarious edges of capitalism, misogyny and the carceral state, to sex work's contested place within both feminism and social movements at large - and explains why sex workers, like all workers, need solidarity and liberation, not cops and punishment. Smith is co-author of the new book

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights

from Verso.' --

This is Hell! Radio

Published on January 19, 2019 07:48

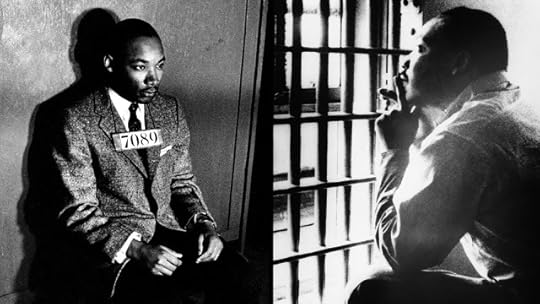

James Earl Jones Reads Excerpts of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"

'James Earl Jones reads an excerpt of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" on January 18, 1988 at the 92nd Street Y.'

'James Earl Jones reads an excerpt of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" on January 18, 1988 at the 92nd Street Y.'

Published on January 19, 2019 07:34

January 17, 2019

Left of Black S9:E10: Oddisee (Amir Mohamed el Khalifa) Talks The State of Hip-Hop and Trump’s America

Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in the studio by acclaimed rapper and producer, Amir Mohamed el Khalifa also known as Oddisee (@ODDISEE). Oddisee visited Durham and Duke University for a weeklong residency in October 2018 as part of Duke Performances’ Hip-Hop Initiative. His albums include The Iceberg (2017), The Good Fight (2015), People Hear What They See (2012), and Starr Status (2006), among others.

Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in the studio by acclaimed rapper and producer, Amir Mohamed el Khalifa also known as Oddisee (@ODDISEE). Oddisee visited Durham and Duke University for a weeklong residency in October 2018 as part of Duke Performances’ Hip-Hop Initiative. His albums include The Iceberg (2017), The Good Fight (2015), People Hear What They See (2012), and Starr Status (2006), among others.

Published on January 17, 2019 07:56

An American Sonnet by Terrance Hayes

'Right after the 2016 election,

Terrance Hayes

began writing a series of poems that all shared the title “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin.” The poems use a traditional form to describe his entirely contemporary experience of being a black man in an America that feels ominously threatening. Hayes’s collection of the poems was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2018. “American Sonnet for the New Year” was published in The New Yorker at the start of 2019, and Hayes read the poem for the New Yorker Radio Hour. It sounds a small, tentative note of hope.' --

New Yorker Radio Hour

'Right after the 2016 election,

Terrance Hayes

began writing a series of poems that all shared the title “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin.” The poems use a traditional form to describe his entirely contemporary experience of being a black man in an America that feels ominously threatening. Hayes’s collection of the poems was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2018. “American Sonnet for the New Year” was published in The New Yorker at the start of 2019, and Hayes read the poem for the New Yorker Radio Hour. It sounds a small, tentative note of hope.' --

New Yorker Radio Hour

Published on January 17, 2019 07:41

January 15, 2019

When Newsrooms Aren't Representative of the Country they Report On, What is at Stake?

'As the 2020 presidential election approaches, newsrooms across the country are starting to assemble their political reporting teams. Recently, CBS News announced their group of 2020 reporters and producers. Of the 12 reporters and producers named, a majority are white, and none are black. But CBS is not the only news organization that has issues when it comes to having a diverse staff. A 2017 survey conducted by the American Society of News Editors found that journalists of color account for just 16.6 percent of newsroom staffs. At WNYC, where The Takeaway is produced, people of color make up 28 percent of the staff. So what’s actually at stake when newsrooms fail to represent the country they report on? Astead Herndon, a national politics reporter for The New York Times, and Darren Sands, a national political reporter for Buzzfeed, join The Takeaway to discuss.' -- The Takeaway

Published on January 15, 2019 20:09

Leyla McCalla Plays the 'Capitalist Blues'

'A New York–born Haitian-American living in New Orleans, the multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla draws from traditional Creole, Cajun, and Haitian music, as well as American jazz and folk. McCalla is a former member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, but her latest record, Capitalist Blues, contains very little of her signature instrument, the cello. While the tunes range from blues to calypso, and folk with some Haitian Creole, she explores connections between New Orleans and Haiti and tries to make sense of the current political "pressure cooker" in which the country finds itself. McCalla and her band perform some of these songs in-studio.' - Caryn Havlik for Soundcheck

'A New York–born Haitian-American living in New Orleans, the multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla draws from traditional Creole, Cajun, and Haitian music, as well as American jazz and folk. McCalla is a former member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, but her latest record, Capitalist Blues, contains very little of her signature instrument, the cello. While the tunes range from blues to calypso, and folk with some Haitian Creole, she explores connections between New Orleans and Haiti and tries to make sense of the current political "pressure cooker" in which the country finds itself. McCalla and her band perform some of these songs in-studio.' - Caryn Havlik for Soundcheck

Published on January 15, 2019 19:59

Claudia Rankine—How Can I Say This So We Can Stay in This Car Together?

'The poet, essayist, and playwright Claudia Rankine says every conversation about race doesn’t need to be about racism. But she says all of us — and especially white people — need to find a way to talk about it, even when it gets uncomfortable. Her bestselling book, Citizen: An American Lyric, catalogued the painful daily experiences of lived racism for people of color. Claudia models how it’s possible to bring that reality into the open — not to fight, but to draw closer. And she shows how we can do this with everyone, from our intimate friends to strangers on airplanes.' --

On Being

'The poet, essayist, and playwright Claudia Rankine says every conversation about race doesn’t need to be about racism. But she says all of us — and especially white people — need to find a way to talk about it, even when it gets uncomfortable. Her bestselling book, Citizen: An American Lyric, catalogued the painful daily experiences of lived racism for people of color. Claudia models how it’s possible to bring that reality into the open — not to fight, but to draw closer. And she shows how we can do this with everyone, from our intimate friends to strangers on airplanes.' --

On Being

Published on January 15, 2019 19:48

Nuestro Paìs Americano: Julian Castro and the Makings of a Latinx Candidacy by Wilfredo Gomez

Nuestro Paìs Americano: Julian Castro and the Makings of a Latinx Candidacy

by Wilfredo Gomez | @BazookaGomez84 | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Nuestro Paìs Americano: Julian Castro and the Makings of a Latinx Candidacy

by Wilfredo Gomez | @BazookaGomez84 | NewBlackMan (in Exile) “Yo soy candidato para Presidente de los Estados Unidos!” And with these words former mayor of San Antonio, Julian Castro announced his candidacy for the Presidency of the United States of America. And in the process he provided a framework that future Latinx candidates will revisit during their respective presidential runs. Amidst the speculation suggesting a major announcement from the Castro camp, I wondered what the context and subtext of such a declaration would bring to the forefront of the American political landscape.

Given a racial paradigm that juxtaposes racial formations that provide us with narratives predicated upon a history of discourses that demarcate fault lines of nature and culture, how would Julian Castro’s brown body deconstruct the multi-layered mine-field of race relations when those very identities afford us mechanisms of institutional and structural inequities that depend on the circulation and pendulum (shifts) of language practices, policies, behaviors, and habits of mind? That would demand that we ask a set of critical question inquiring into how Julian Castro subverts a history of race relations, such that his Mexican body (and experiences) reframes a conversation about the role of Latinxs in the contemporary political moment, and how those bodies are ever-present in the history and histories of this country (both written and shared through oral history). Moreover, in raising these questions we might further inquire into how we imagine potential voters to receive and project themselves into Julian Castro’s American story, or more provocatively, Julian Castro’s America.

I raise this point thinking about the contemporary moment and the ways in which discourses on alleged national security and humanitarian crises, a government shutdown, and calls for a wall, further serve to reinforce an ideology that essentially contributes to the Mexicanization of the Latinx community (not excluding efforts that further demonize and pathologize with consequences faced by that same community, rendering them collateral damage). It is within this context, that I both read and analyze Castro’s campaign announcement through the context (and substance) of then Senator Barack Obama’s “A More Perfect Union Speech” delivered on March 18, 2008.

Obama’s speech offered us a unique window into the characterization of history that sought to parcel out the players, agents of change, and power dynamics that inherently tie the actions of the past to the color palette of the present. And with those words, Obama ushered in an American story that far too often fails to circulate beyond the classrooms of high school history curriculums. This was Obama’s take on Howard Zinn’s classic A People’s History of the United States. Julian Castro has contributed more pages to that history in progress, as embodied through our very beings.

I shared news of Castro’s announcement and the first responses were, “Good. I’ll vote for him in a heartbeat,” and “It would be nice to have a Hispanic be President,” words spoken by someone with roots in Latin America and the English-speaking Caribbean and a Puerto Rican respectively. These responses, while far from reliable ethnographic data, offer a fascinating frame of reference into the possible series of qualitative responses that substantiate assessments regarding the significance of Castro’s candidacy for Latinx communities and the broader American public.

More importantly, it begs the query of whether or not Julian Castro’s announcement will provide a cultural script that serves as a blueprint from which subsequent Latinx candidates can sample from, signify upon, and inherit on a national stage. Such a stance affords future Latinx candidates a political paradigm, effectively transforming their newness (on the national stage) into legible patterns of representation that resonate across geographical, ideological, political, gendered, and raced cartographies of difference as indexed by national elections and partisan politics that makes one likeable, electable, and relatable.

This is something that Obama did so well in transcribing and translating an autobiographical journey that tapped into the historical, structural, and institutional forces of difference and indifference, both effectively excavating and illuminating the American emotional heart strings that tie individuality to collective notions of susceptibility, vulnerability, community, and ultimately, American identity. Forged at the nexus of the exceptional and everyday, Obama hit the American public with a political eurostep that was equal parts James Harden and Luka Doncic. Thus, there was a masterful undertaking of political physics that was predictable, yet effective, unstoppable and efficient, simply, mesmerizing: an homage that payed attention to the forces of the present, while alluding to the evolution and changing landscape of American demographics, liberal sentiment, and the audacity of hope as embodied in the ghostly presence of rhetorics and bodies that harnessed the spirits of resistance and resilience, confrontation and compassion, diversity and democracy, indifference and inclusion, its (the country’s) tragedies as well as its triumphs, a counter (and contrast) to the demagoguery of the likes of Donald Trump.

The brilliance of “A More Perfect Union” came in its execution and tone, a cadence that carved through white noise, allowing America to bare its soul by proxy, its (surgical) sutures on display as collective shortcomings and sufferings as embodied (and enacted) in the moral fabric and genetic makeup of a man descended from a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas. In what is now a classic (Obamaesque) delivery, the then Senator spoke not only as a black man implicated in processes of racialization and forces of inheritances beyond his control, he spoke to and gave legibility and visibility to a language highlighting the inherently rhizomorphic nature of blackness, a dynamic and nuanced script of embodiment, performance, and perhaps even autobiography that was pure Americana, yet something else, the familiar and the foreign.

Capturing these productive tensions as mediated through one body, Obama opened the doors to America’s racial pandora's box. In so doing, he spoke of histories that sought to implicate all of us, particularly the voting public, in the original sin of America’s wrongdoings, and its capacity to see through that, rupturing static notions of possibility that afforded seamless connections to be made between middle America and mainstream America, urban and rural America, black and white America, the formally and informally educated, the rich and poor, and the interstitial gradations of iteration that give us a broadened palette of colors from which to name, claim, own, and speak our individual and collective stories. Framed in this way, Obama was able to invoke American’s bootstrap narrative, affording himself leverage to critically engage, illuminate, problematize and unpack the dominant tropes of blackness and whiteness we inherit, perform and exercise, a package utilized (daily) to promote and reinforce discourses, rhetorics, and policies of indifference, pathology, backwardness, and the unknown. The answer to the question, can we talk about it, was a resounding and thunderous, “Yes We Can!”

January 12, 2019 marked Julian Castro’s own Si Se Puede moment. Much like Obama’s “A More Perfect Union,” Castro constructed and narrativized his own genealogies of history, a generational tale of loss, aspiration, hope, and legacy. An orphaned grandmother Victoria, arriving from Mexico at the age of 7, who worked as a maid, babysitter, and cook, and who’s daughter (Rosie), would be a first-generation college graduate and activist. In just two generations, the Castro’s would be graduates of Stanford University and Harvard Law School, occupying positions such as mayor of San Antonio, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, and Chairperson of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (Joaquin). But aside from the autobiographical tales that further cemented ideologies of rugged individualism and dogged determination, Castro put forth his own synopsis of American history, punctuated by tying the local stories of San Antonio to the national aspirations and consciousness of the United States of America.

For Castro, difference as he posited it, was not a matter of defining or evaluating intelligence or drive, but rather the labor involved in parceling out how a break in life can be complicated, when analyzed from the perspective of how discourses centering on equality of opportunity are rarely, if ever balanced out, by public calls for conversations around equality of conditions on the one hand, and equality of outcomes on the other.

In constructing and owning his own difference, Castro shunned any would be labels of exceptionalism, as did Obama. However, in doing so, he was afforded an opportunity to discuss a larger brand of exceptionalism tying the local to the national. With effective oratorical skill, Castro suggested that the existing and budding cosmopolitanism of San Antonio was and could be the future of the country, whereby a community of immigrants incorporates Mexico, Germany, and those rendered “other.” The contributions of those publicly rendered disposable or invisible by a “crisis of leadership” were now emboldened and enabled by being spoken into existence. Thus, Native Americans received a shout out, as did the lives of fellow American citizens residing in Puerto Rico. Black and brown Unity was invoked, as the importance of the Black Lives Matter movement was made central to the practice of democracy-- where the names of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Aiyana Jones, and others reverberated loudly, a cultural commentary and public remembrance that served as a springboard for a critique of state sanctioned violence, white privilege, criminal justice reform, and a broken and deeply flawed immigration system. The rights, needs, and lives of vulnerable and overlooked populations were acknowledged as LGBT youth and the homeless were spoken into existence in a political arena that erases their bodies and memories through rhetorics cheapened by invocations of middle-classness or the dilution of the vulnerable as being monopolized by one specific group above all others.

As I digested Castro’s words and revisited them throughout the day, seeking to contextualize them within the framework of Obama’s speech and Castro’s own remarks at the 2012 DNC meeting, I asked myself, as I ask you, dear reader, as a prominent Latinx figure with impeccable credentials and experiences, does this represent the makings of a Latinx candidacy, one that presents a legitimate case for being a contender to occupy the highest seat in the nation’s most powerful office? I offer these particular thoughts after years of conversations with friends and colleagues about the makings of a Latinx public intellectual and what the implications and meaning of such a series of queries entails.

I revisit that very question not only wanting to think through what it means for Castro to take his narrative and message national, but to further challenge myself and others to think through the viability and transferability of Castro’s Latinx America, vis-a-vis the equally as rhizomorphic nature of how Latinxs frame, embody, and perform their own personal histories of journeys and movements to los Estados Unidos. What do we take away from Castro’s announcement that has implications for the next Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Peruvian, or Dominican that too, seeks to ascend the heights of the Presidency? What about those Latinxs who are further complicating what it means to be Latinx, having ancestry that is also African-American, African, Asian, and yes even Native-American? Not to be forgotten are those Latinx community members scholar Frances Aparicio would call “IntraLatinos,” those Latinxs who belong to two or more nationalities within the Latinx community: figures who are all transforming and remixing what it means to be Latinx in America.

MSNBC’s Alex Witt and Michael Steele implicitly pondered these thoughts in the aftermath of Castro’s announcement, dialoguing about the viability of Castro’s narrative and overall candidacy as it becomes translated through the lens of geographical difference, local demographics, and processes of socialization. They followed up on Castro’s speech, perhaps unintentionally and unconsciously, with a story about Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (an elected official from New York of Puerto Rican heritage), or as she is playfully, if not disrespectfully referred to as “AOC.”

Given how groundbreaking and impactful these figures have already proven themselves to be, the semantics matter just as much as the context and the politics. Media pundits lack the critical lens (or self-reflexivity) that shines attention on any possible rationale behind why Ocasio-Cortez might push back on both Democrats and Republicans, in addition to why she takes a proactive approach in simply voicing her concerns/opinions, in light of only recently being sworn into Congress. Collectively, these responses represent a lack of self-awareness regarding who and what Latinx politicians can be across a broad spectrum of differences.

A failure to recognize this as a fact of our current realities (as evidenced in Ocasio-Cortez being dismissed with the musings as to whether or not we will see her “do the ChaCha sometime”) and our collective becomings echoes the words spoken by Castro during his announcement, namely that, “if you don’t respect us, you must expect us.”

+++

Wilfredo Gomezis an independent scholar and researcher. He can be reached at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.com or via twitter at @BazookaGomez84.

Published on January 15, 2019 16:13

January 13, 2019

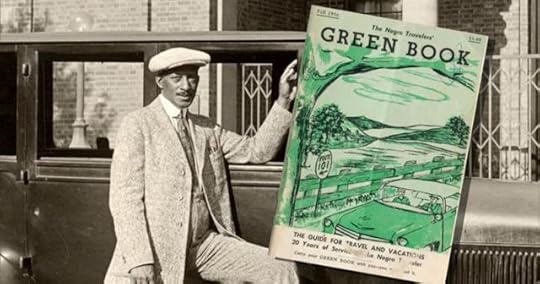

Traveling with "The Green Book" during the Jim Crow era

'Racism was a chilling fact of life that, in 1936, inspired "The Negro Motorist Green Book," a guide to businesses that welcomed African American travelers who faced being turned away or threatened in a time of segregation. Martha Teichner talks with cultural historian Candacy Taylor about the importance of this guide to safe travels in the Jim Crow South.' -- CBS Sunday Morning

'Racism was a chilling fact of life that, in 1936, inspired "The Negro Motorist Green Book," a guide to businesses that welcomed African American travelers who faced being turned away or threatened in a time of segregation. Martha Teichner talks with cultural historian Candacy Taylor about the importance of this guide to safe travels in the Jim Crow South.' -- CBS Sunday Morning

Published on January 13, 2019 13:35

New Yorker Radio: Boots Riley, Janet Mock, and Chris Hayes

'In live conversations at the New Yorker Festival, the writer Janet Mock talks with Hilton Als about learning self-acceptance from Hawaiian culture, the musician and director Boots Riley talks about the power of art as a political tool, and MSNBC’s Chris Hayes reflects on the toll of hosting a daily news show in the age of Trump.' -- The New Yorker Radio Hour

'In live conversations at the New Yorker Festival, the writer Janet Mock talks with Hilton Als about learning self-acceptance from Hawaiian culture, the musician and director Boots Riley talks about the power of art as a political tool, and MSNBC’s Chris Hayes reflects on the toll of hosting a daily news show in the age of Trump.' -- The New Yorker Radio Hour

Published on January 13, 2019 05:20

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.