Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 410

January 24, 2019

Dr. Melina Abdullah Discusses Persecution Of Black Activists

'Dr. Melina Abdullah Discusses Persecution Of Black Activists with Margaret Prescod host of

Sojourner Truth

.'

'Dr. Melina Abdullah Discusses Persecution Of Black Activists with Margaret Prescod host of

Sojourner Truth

.'

Published on January 24, 2019 08:10

Colman Domingo Speaks On "If Beale Street Could Talk"

'Through the unique intimacy, power of cinema and Barry Jenkins' incredible vision, If Beale Street Could Talk honors James Baldwin's prescient words and imagery, charting the emotional currents navigated in an unforgiving and racially biased world as the filmmaker poetically crosses time frames to show how love and humanity endure. Colman Domingo came to BUILD Series to discuss the film and his role.'

'Through the unique intimacy, power of cinema and Barry Jenkins' incredible vision, If Beale Street Could Talk honors James Baldwin's prescient words and imagery, charting the emotional currents navigated in an unforgiving and racially biased world as the filmmaker poetically crosses time frames to show how love and humanity endure. Colman Domingo came to BUILD Series to discuss the film and his role.'

Published on January 24, 2019 08:05

A Changing Nation, A Nation in Need of Change: Review of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power by Sasha Panaram

Art Is..., Lorraine O'Grady, 1983

Art Is..., Lorraine O'Grady, 1983 A Changing Nation, A Nation in Need of Change: Review of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Powerby Sasha Panaram | @SashaPanaram | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I seldom travel to Brooklyn, New York but whenever I do there is only ever one destination to which I go: the Brooklyn Museum. In December 2018, as one year came to a close and another was on the brink of beginning, I found myself at the Brooklyn Museum not once, not twice, but three times. Although my repeated trips brought me to the same exhibit, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, each day, I would be lying if I said that I witnessed the same set of art with every increasing visit.

What I mean to say but cannot quite say and perhaps will only begin to say here is that Soul of a Nation necessitates more than one visit. It demands more than one look. Its very composition invites, creates, and celebrates return.

On display until February 3, 2019, Soul of a Nation features a wide range of black artistic practices from 1963 to 1983. Covering the span of two decades, the exhibit attends to a hotly revolutionary period in American history that witnessed the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power Movement, protests against the Vietnam War, Watergate, the space race, and second wave feminism, among other things. With more than 150 artworks from more than 60 artists, Soul of a Nation provides an extended look into how artists worked individually, in communities, and in collectives to create pieces that responded to societal pressures, setbacks, and triumphs.

By bringing together works of print, photography, performance, painting (figuration and abstraction), assemblage, and sculpture in one exhibit, Soul of a Nation demonstrates the varied aesthetic practices black artists utilized to make sense of the world as well as bold forms of experimentation undertaken to create new aesthetics altogether.

When Soul of a Nation first exhibited at the Tate Modern in London on July 12, 2017, the show co-curated by Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley, along with assistant curator, Priyesh Mistry, preceded the violence that erupted in Charlottesville, Virginia by exactly one month. No one painting better exemplified the tensions that mounted in Charlottesville than Norman Lewis’s “America the Beautiful” (1960). On first glance, the painting depicts white spotted streaks against a pitch-black backdrop. But a closer look reveals the peaked hoods of the Ku Klux Klan marching with flaming crosses. In 2017, “America the Beautiful” suggested all too vividly that the dreams of civil rights leaders had hardly been realized. In 2018 (and now 2019), the same painting spurs a new set of questions in the Brooklyn Museum: Which parts of America are beautiful? If there is indeed beauty to be found in this country where might it reside? Who will show us?

“America The Beautiful” (1960), Norman Lewis Whereas Soul of a Nation’s inclusion at the Tate Modern offered viewers in the United Kingdom one of the first opportunities to see late twentieth century black American art on display in one gallery, the exhibit’s premiere at the Brooklyn Museum in September 2018 seems like a natural extension of the Museum’s ongoing commitment to black diasporic art and culture. In fact, those familiar with some of the more recent exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum might understand Soul of a Nation, assembled by assistant curator and Ph.D. candidate in English and African American Studies at Yale University, Ashley James, as in conversation with We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965 – 1985 (April to September 2017) or The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America (July to October 2017).

“America The Beautiful” (1960), Norman Lewis Whereas Soul of a Nation’s inclusion at the Tate Modern offered viewers in the United Kingdom one of the first opportunities to see late twentieth century black American art on display in one gallery, the exhibit’s premiere at the Brooklyn Museum in September 2018 seems like a natural extension of the Museum’s ongoing commitment to black diasporic art and culture. In fact, those familiar with some of the more recent exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum might understand Soul of a Nation, assembled by assistant curator and Ph.D. candidate in English and African American Studies at Yale University, Ashley James, as in conversation with We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965 – 1985 (April to September 2017) or The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America (July to October 2017). But like all major cultural institutions, the Brooklyn Museum, too, once struggled with questions concerning representation and accessibility. In 1968, responding to a set of protestors who accused the Museum for failing to feature artwork from black artists in their surrounding neighborhood, the Brooklyn Museum formed a Community Gallery. Under the direction of activist and curator, Henri Ghent, the Community Gallery not only provided exhibition space for local artists, but it also supplemented exhibitions with newsletters, an Artists in Residence program, and neighborhood discussions.

With this particular institutional history in mind, Soul of a Nation not only complements previous shows, but it also continues to raise awareness about the breadth of black artistic expression locally, nationally, and internationally.

Soul of a Nation starts on the fifth floor of the Museum where it is organized geographically. The show fittingly begins in New York in 1963 featuring 15 painters including Romare Bearden, Charles Alston, Hale Woodruff, and Norman Lewis who comprised the Spiral Group. The Spiral Group also included one woman, Emma Amos, who at the age of 25 was the youngest member of the group.

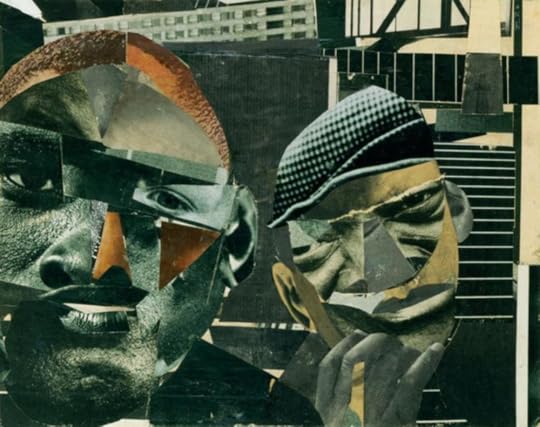

Initially formed with the intention of organizing a bus trip to the March on Washington, the group began meeting regularly in Bearden’s studio to discuss whether art should respond to politics and if such a thing as a “Negro” aesthetic existed. At the time, Bearden had begun creating collages, which would become a signature characteristic of his oeuvre. However, other artists such as Lewis and Alston made paintings that altered between figuration and abstraction or sometimes considered the two together.

The Spiral Group never did settle on a single aesthetic but in 1965 they held one show in Greenwich Village where each artist produced his or her social commentary in black and white. As such, some of the works featured in this section of Soul of a Nation include Romare Bearden’s massive photomontages alongside Norman Lewis’s “Processional (aka Procession)” (1965).

“Pittsburgh Memory” (1964), Romare Bearden Adjacent to the Spiral Group is a smaller display that contains photography from The Kamoinge Workshop. “Kamoinge” is Kenyan for “a group of people working together.” Made of black photographers who assembled in Harlem in 1963, the group operated under the leadership of Roy DeCarava, whose use of velvety shadows and dark tonal ranges created an unparalleled richness to his work. While not all Kamoinge members shared DeCarava’s aesthetic choices part of what drew them together was their attentiveness to, even reverence for, black quotidian matters. To that end works in this section capture urban life, familial relationships, and activism that unfolded across New York City.

“Pittsburgh Memory” (1964), Romare Bearden Adjacent to the Spiral Group is a smaller display that contains photography from The Kamoinge Workshop. “Kamoinge” is Kenyan for “a group of people working together.” Made of black photographers who assembled in Harlem in 1963, the group operated under the leadership of Roy DeCarava, whose use of velvety shadows and dark tonal ranges created an unparalleled richness to his work. While not all Kamoinge members shared DeCarava’s aesthetic choices part of what drew them together was their attentiveness to, even reverence for, black quotidian matters. To that end works in this section capture urban life, familial relationships, and activism that unfolded across New York City. While the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 may have intimated that the nation was prepared to confront its history of racial exclusion, the vitriol that accompanied the years immediately before and after this bill told another story. The assassination of Medgar Evers in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 inspired a new generation of black artists to explicitly address racial injustice.

In New York, black artists made demands on the art world that established new institutions. For instance, both the Studio Museum and El Museum del Barrio opened in 1968 and 1969 respectively in Harlem and East Harlem. 1969 marked the founding of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), a group that advocated for the hiring of African American curators in New York City museums.

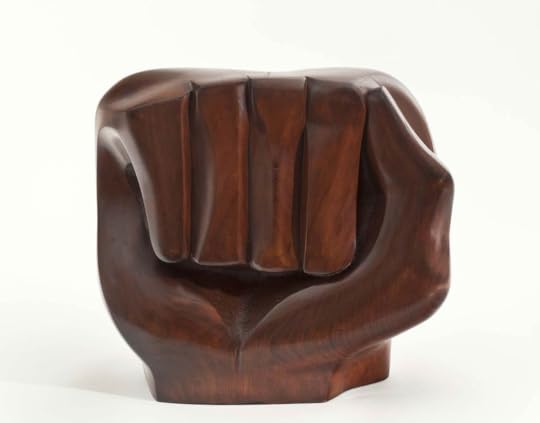

Paying homage to this moment, Soul of a Nation prominently displays Elizabeth Catlett’s massive mahogany sculpture, “Black Unity” (1968). Behind Catlett’s “Black Unity” hangs Faith Ringgold’s “The Flag is Bleeding” (1967), a harrowing painting of white and black faces peering through bloodied stars and stripes. Taken together these two works articulate the fraught relationship between racial pride and American nationalism. They point to a country that never was and still is not able to honor, let alone account for, the lived experiences of black Americans.

“Black Unity” (1968), Elizabeth Catlett Another gallery on the fifth floor contains pieces inspired by the Watts Rebellion in 1965 with work from Betye Saar, Melvin Edwards, Noah Purifoy, and John Outterbridge, each of whom worked in assemblage. Most striking is Saar’s “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972) that repositions a derogatory mammy figurine by painting her with a broom in one hand and a riffle in the other. Credited by Angela Davis for initiating the black women’s movement, Saar’s “Liberation of Aunt Jemima” is a clarion call for justice.

“Black Unity” (1968), Elizabeth Catlett Another gallery on the fifth floor contains pieces inspired by the Watts Rebellion in 1965 with work from Betye Saar, Melvin Edwards, Noah Purifoy, and John Outterbridge, each of whom worked in assemblage. Most striking is Saar’s “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972) that repositions a derogatory mammy figurine by painting her with a broom in one hand and a riffle in the other. Credited by Angela Davis for initiating the black women’s movement, Saar’s “Liberation of Aunt Jemima” is a clarion call for justice. “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972), Betye SaarThe largest gallery on the fifth floor, which features the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) from the South Side of Chicago, is hard to miss not because of its size but because of its extravagant colors. Largely known for their “Wall of Respect” mural, OBAC painted images of writers, athletes, dancers, and civic leaders across the country.

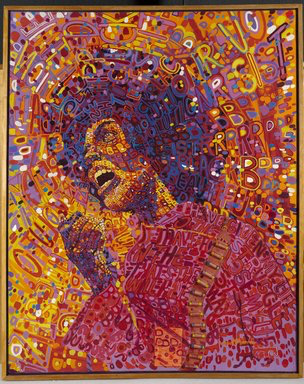

“The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972), Betye SaarThe largest gallery on the fifth floor, which features the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) from the South Side of Chicago, is hard to miss not because of its size but because of its extravagant colors. Largely known for their “Wall of Respect” mural, OBAC painted images of writers, athletes, dancers, and civic leaders across the country. With the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. several OBAC members formed the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA) to more explicitly address liberation causes. Utilizing a similar bright neon color palette particular to OBAC, AfriCOBRA unveiled kaleidoscopic portraits of leaders such as Malcolm X and Angela Davis.

“Revolutionary (Angela Davis)” (1971), Wadsworth A. JarrellIf the fifth floor of Soul of a Nation takes geography as its organizing principle, then the fourth floor cultivates a space based on aesthetic exploration.

“Revolutionary (Angela Davis)” (1971), Wadsworth A. JarrellIf the fifth floor of Soul of a Nation takes geography as its organizing principle, then the fourth floor cultivates a space based on aesthetic exploration. However, before one can even enter the fourth floor exhibit they are greeted by Sam Gilliam’s most stunning piece, “Carousel Change” (1970). Draped marvelously from the ceiling, “Carousel Change,” which is neither paining nor sculpture, stops you in your tracks. Literally. Without fail each day I visited the Brooklyn Museum so captivated were visitors by its majestic presence – indeed it looks like an elevated crown – that the stairway remained bottled necked. Whereas, ordinarily this type of foot traffic poses a problem instead it provided a welcomed opportunity to stop, look again, and relish in Gilliam’s creative genius. Much like the rest of Soul of a Nation, Gilliam’s “Carousel Change” makes you wonder what it took – what kind of labor, what kind of societal circumstances, what kind of courage – to make this.

“Carousel Change” (1970), Sam Gilliam The remainder of the fourth floor explores issues as teasingly diverse as how to represent black bodies, how to engage with surfaces, and how to parse the relationship between movement and action. The artwork here, like Gilliam’s “Carousel Change,” is not intended purely for viewership but rather to be experienced. Artists like Joe Overstreet and Sengu Nengudi deliberately push the limits of what is expected of certain materials.

“Carousel Change” (1970), Sam Gilliam The remainder of the fourth floor explores issues as teasingly diverse as how to represent black bodies, how to engage with surfaces, and how to parse the relationship between movement and action. The artwork here, like Gilliam’s “Carousel Change,” is not intended purely for viewership but rather to be experienced. Artists like Joe Overstreet and Sengu Nengudi deliberately push the limits of what is expected of certain materials. The very last section of Soul of a Nation – one that could be easily overlooked – is a small room with music from Nina Simone, Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, and Billie Holiday looping on repeat set against a recorded performance of Houston Conwill’s “Cake Walk” (1983). In a not so subtle send-off, visitors are reminded to keep their ears peeled as they leave remembering that sight is but one way to experience the past.

Soul of a Nation provides a thorough examination of what is possible when people choose to express themselves, even assert themselves, in a changing nation, a nation they wish to see changed.

The extraordinary richness that is Soul of a Nation necessarily begs the question, “how does one begin to organize a show of this magnitude?” Responding to this point exactly, James said, “[i]t really required me to believe that I could do it. I credit my institution for giving me a large responsibility. That first gesture of faith in me was essential. But I didn’t let a doubt around whether or not it was something I could accomplish ever really enter the picture.”

This fearlessness that undergirds James’s response – this indisputable boldness of vision – strikes me as similar to what I imagine inspired the artists in Soul of a Nation. With no single black aesthetic that could represent the multiple revolutions from the 1960s to 1980s, artists had to believe just as much in what they were doing as how they were doing it. With little time to hesitate, they needed to act and act courageously no less. The products of that courage – the results of their daring experimentation – is an exhibit worthy of many trips even if that means making the trek to Brooklyn from the Bronx.

+++

Sasha Panaram (@SashaPanaram) is a Ph.D. student (ABD) in English at Duke University. A Georgetown University alumna, her scholarly interests are in Black diasporic literature, black feminisms, and visual cultures.

Published on January 24, 2019 07:09

January 23, 2019

The Dark History Behind the 'Father of Modern Gynecology'

'For 80 years, a bronze statue of 19th-century doctor James Marion Sims stood in New York City’s Central Park. Sims's major achievement was developing a technique to repair painful fistulas, or tears resulting from childbirth often between the birth canal and the urethra or rectum. He has often been called the "father of modern gynecology."But public outrage about how Sims did that work -- by experimenting on enslaved black women -- forced NYC officials to finally remove the statue in 2018.Playwright Charly Evon Simpson's new play Behind the Sheet reckons with Sims’ work and the women who had to suffer for it.' --

The Takeaway

'For 80 years, a bronze statue of 19th-century doctor James Marion Sims stood in New York City’s Central Park. Sims's major achievement was developing a technique to repair painful fistulas, or tears resulting from childbirth often between the birth canal and the urethra or rectum. He has often been called the "father of modern gynecology."But public outrage about how Sims did that work -- by experimenting on enslaved black women -- forced NYC officials to finally remove the statue in 2018.Playwright Charly Evon Simpson's new play Behind the Sheet reckons with Sims’ work and the women who had to suffer for it.' --

The Takeaway

Published on January 23, 2019 04:25

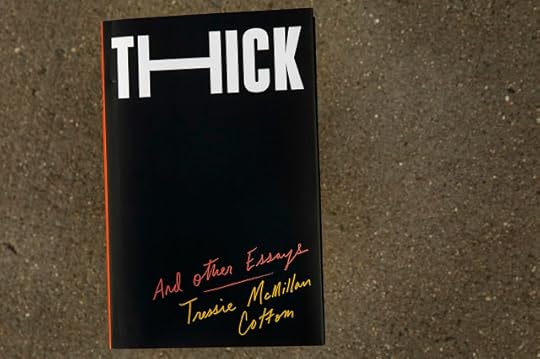

In 'Thick,' Tressie McMillan Cottom Looks At Beauty, Power And Black Womanhood In America

'Beauty. Politics. Inequality. Gender. Money. Familiar themes endlessly discussed. But are we hearing every essential voice? Rhetorical question, because the answer is obviously no. In her new collection of essays,

Tressie McMillan Cottom

says her work is animated by what’s still seen as a “radical idea … black women are rational and human.” From that assumption, she works her way analytically through politics, economics, history, sociology and culture. “It rarely fails me,” she says.' --

WBUR's On-Poiint

'Beauty. Politics. Inequality. Gender. Money. Familiar themes endlessly discussed. But are we hearing every essential voice? Rhetorical question, because the answer is obviously no. In her new collection of essays,

Tressie McMillan Cottom

says her work is animated by what’s still seen as a “radical idea … black women are rational and human.” From that assumption, she works her way analytically through politics, economics, history, sociology and culture. “It rarely fails me,” she says.' --

WBUR's On-Poiint

Published on January 23, 2019 04:19

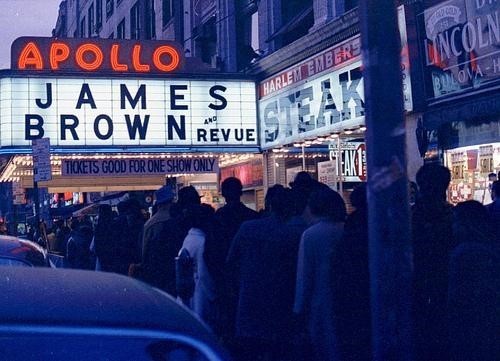

Apollo Live Wire – Re-Volution Live: 50 Years After Say It Loud

'Fifty years after the release of James Brown’s hallmark anthem, Apollo Live Wire brought together a lineup of acclaimed artists and thinkers to reflect on the impact of that pivotal song in music history. Duke University Professor of African and African American Studies, Mark Anthony Neal; bassist, composer and host of Jazz Night in America, Christian McBride; and three special guest DJs: DJ KS 360, DJ Likwuid, and DJ MamaSoul, come together for an improvised evening of music and conversation.'

'Fifty years after the release of James Brown’s hallmark anthem, Apollo Live Wire brought together a lineup of acclaimed artists and thinkers to reflect on the impact of that pivotal song in music history. Duke University Professor of African and African American Studies, Mark Anthony Neal; bassist, composer and host of Jazz Night in America, Christian McBride; and three special guest DJs: DJ KS 360, DJ Likwuid, and DJ MamaSoul, come together for an improvised evening of music and conversation.'

Published on January 23, 2019 04:09

January 20, 2019

Let Me Bang Your Box: The Erotic Life of the Blues by Mark Anthony Neal

Let Me Bang Your Box: The Erotic Life of the Blues by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

It was perhaps fitting that the opening scene of 12 Years a Slave – a film that in its most effective moments captured the everydayness of the brutality of slavery – begins with another index of everydayness; the pursuit of some semblance of an erotic life amidst that brutality. The scene features Solomon Northrup, in what amounts to the kind of public, yet private space that defined a slave citizenry – “manually ” bringing an unnamed and presumably unknown enslaved women to climax. The scene was described by one reviewer as a “painful sexual encounter” where the “woman's desperation, Solomon's reserve, and the fierce sadness of both, is depicted with an unflinching still camera which documents a moment of human contact and bitter comfort in the face of slavery's systematic dehumanization.”

To make less of a poetic or cinematic point, it was that moment of erotic release, as fleeting as one can only expect under any conditions, and performed by Northrup with the workmanlike quality he displayed throughout the film – that allowed many the ability to see another day or to make “a way out of no way” to make a more explicit existentialist point. Writing about the scene in the essay “Searching for Climax: Black Erotic Lives in Slavery and Freedom”, historians Jessica Marie Johnson and Treva Lindsey note, “the sight of her, anonymous and silently demanding to be pleasured, is visually unfamiliar and a departure from the original text...Her sexual encounter unveils her desire to be felt, seen and aroused.”

The genius of the scene as captured by director Steve McQueen was that within a system in which Black bodies were rendered as little more than instruments of Capitalist ambition, they were often forced to be the instruments of their own erotic lives, pleasure reduced to the use of the same digits that harvested cotton, tobacco and indigo. That the enterprise would create an entire cottage industry erected around the shame of Black sexuality should not surprise.

The title of this essay is drawn from two sources: Sharon Patricia Holland’s book The Erotic Life of Racism and The Toppers’ 1954 single “(I Love to Play Your Piano) Let Me Bang Your Box.” In the former Holland critiques the everydayness of anti-Black racism and the ways in which it is sustained via its embodiment within desire and the erotic – hence its continued power. In the latter, the Toppers track, which was compiled more than 20 years ago in a collection called Risque Rhythm: Nasty 50s R&B , highlights the erotic life of Black bodies, literally at the level of an instrument: “play your piano; Bang your box.”

Yet the curatorial decision to frame such a collection as “nasty R&B,” treating Black desire and eroticism as something bordering on pathological, yet available for public consumption and surveillance, highlights the fraught relationship of the private and even illicit dimensions of erotic Black lives and the necessity to locate a public and private humanity, more than a century after Emancipation.

That popular Black music would be the site (and source) of such discourse, should also not surprise. And here it is also important to think about the Blues, as less a generic form of Black music, but as an aesthetic resource – a sonic and performative archive, if you will – that would inform future Black musics, such as R&B (or rough-and-Black, as James “Thunder” Early describes it in the cinematic treatment of the musical Dreamgirls), and even late 20th century rap music.

For many Black Americans, music was the site in which intimacy could be realized, and as Angela Davis points out in her book Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, there were political ramifications. Writing about Black life immediately after emancipation, Davis notes “For the first time in the history of the African presence in North America, masses of black women and men were in a position to make autonomous decisions regarding the sexual partnerships they entered. Sexuality thus was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meanings were expressed.” (4)

With the advent of the phonograph and more access to the private consumption of music, the connection between music and Black intimacy became more concrete. As Davis attest about the Blues tradition that emerges in the 1920s, “the most obvious ways in which blues lyrics deviated from that era’s established popular musical culture was their provocative and pervasive—including homosexual—imagery.” (3). This was the music of a generation of Black folk—two generations removed from slavery and still suffering Jim Crow—for which the sensual and erotic use of their bodies were acts of survival, sustenance, pleasure and even resistance.

Though raucous forms of Blues may have had a hearing in public spaces (where everyone was an adult and up for a good time), in many cases this was music intended for consumption in the private spaces of Black life, as was the case with Jelly Roll Morton’s 17-minute “Make Me a Pallet,” which contains the classic line "give me that p*ssy, let me get in your drawers/I'm gonna make you think you f*ckin' with Santa Claus."

Still the production and circulation of musical narratives of the Black erotic, within the context of the commercial music industry, and including the ambivalent relationship of the recording industry and White publics with what might be viewed as profane, enacted important labor towards attempts to fully realize both Black humanity and citizenship. The moral and at times extra-legal policing of Black erotic lives, necessitated modes of expression that provocatively mocked a nation that kept such eroticism at arms length, even as it was, in part, the source of American empire – if we are to consider the inner workings of Black erotic lives and their relationship to the literal labor of empire – and coyly pushed the boundaries of acceptable public discourse that was bound to be subject to sanction both within and beyond Black communities.

While some of these narratives attempt to celebrate Black male virility and stamina in response to the need to mute certain performances of public Black masculinity – thinking here of The Dominoes’ “Sixty Minute Man” as one example – notable was the centrality of Black female desire and pleasure within those narratives. As Davis observes, “denial of sexual agency was in an important respect the denial of freedom for working-class Black women.” (44) It should not be missed, recalling that scene in 12 Years a Slave, that it was that unknown and unnamed Black women who actively directed the action; his fingers were her instrument of pleasure.

+++

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished professor of African American Studies at Duke University where he chairs the Department of African and African American Studies and hosts the weekly webcast, Left of Black. He is the author of several books including What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture (1999); Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic (2002); and Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities (2013). Follow him on Twitter @newblackman.

Published on January 20, 2019 07:47

January 19, 2019

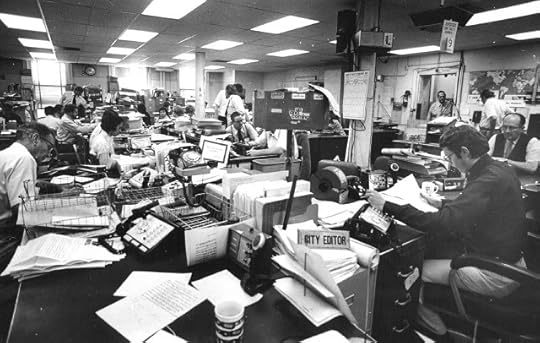

Why Some Journalists Have A Hard Time Saying The Word 'Racist'

'In the fallout of Rep. Steve King's remarks to The New York Times, journalists have been struggling over whether or not to use the word "racist" to characterize his quote.' -- Code Switch

'In the fallout of Rep. Steve King's remarks to The New York Times, journalists have been struggling over whether or not to use the word "racist" to characterize his quote.' -- Code Switch

Published on January 19, 2019 08:53

Outside the White Newsroom: Journalist Aaron Miguel Cantú on the White Press and White Supremacy

'Journalist Aaron Miguel Cantú explains what a White press won't write about White supremacy - from the newsmedia's unwillingness to confront the oppressive structures at the foundation of American society and within its own industry, to the ways 'impartiality' lets journalists off the hook for their own, collective blindspots when it comes to seeing color in American life. Cantú wrote the article "The Whitest News You Know" for The Baffler.' -- This Is Hell! Radio

'Journalist Aaron Miguel Cantú explains what a White press won't write about White supremacy - from the newsmedia's unwillingness to confront the oppressive structures at the foundation of American society and within its own industry, to the ways 'impartiality' lets journalists off the hook for their own, collective blindspots when it comes to seeing color in American life. Cantú wrote the article "The Whitest News You Know" for The Baffler.' -- This Is Hell! Radio

Published on January 19, 2019 08:43

'Barely Treading Water': Why The Shutdown Disproportionately Affects Black Americans

'As the government shutdown enters its fourth week, federal workers are struggling to make ends meet. But according to Jamiles Lartey, the shutdown is having a disproportionate effect on Black workers.' --

NPR Code Switch

'As the government shutdown enters its fourth week, federal workers are struggling to make ends meet. But according to Jamiles Lartey, the shutdown is having a disproportionate effect on Black workers.' --

NPR Code Switch

Published on January 19, 2019 08:31

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.