Paul O'Connor's Blog, page 4

August 25, 2022

What is in a Word - An Article for Emigre Travel

I was asked to a do a little creative writing on the themes of leaving and returning for Emigre Travel… here is the first paragraph. Head to the site for the full article and some ace art by Melanie Garcia.

A life-sized rendering of a wild pig in an Indonesian cave points to some of our earliest evidence of the origins of human culture. Depicted in red ochre it dates back an estimated 35,000 years, a signpost to early human symbolic thinking. The cave painting suggests a desire to communicate, to reach outwards and beyond oneself. It is a rendering of the natural world and represents something of shared importance to a community. Provocatively this cultural artefact narrows the gap between then and now, us and them. The similarity of such Neolithic depictions in caves in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Western Europe all point to our enduring global connections. In the long durée it is unremarkable to state we have always been wanderers. We are a species that oscillate between significant places of our own making, locations where we leave our marks in footprints, scrawls, and constructions.

The urban historian Lewis Mumford provides an edifying remark, that the very first settlements were ‘cities of the dead’. What he meant by this was that early human culture recognised the significance of lasting communal bonds so much so, that graves became points of orientation, places to return to. Perpetual and nomadic movement slowly gave way to festive retreats, seasonal hunting lodges, and garden hovels. Gradually the balance shifted, and these sites were no longer considered destinations, but homes. A flux emerged changing human momentum from an outward orientation, a moving beyond orchestrated by the seasons and migrations of other species, to a turning inwards. Settlements acted as a centrifuge. They gave us a reason to return and punctuated our existence with an attachment to place. Becoming a person of a ‘particular’ place and ‘time’ also anticipated the association that a traveller has a point of origin, that they have chosen to leave and become an émigré.

What is in a word? In parsing a term such as ‘émigré’ one must reach through the past and contextualise its dense imaginings. Some ingredients seem essential such as movement and choice, others like duration, intention, and return are more nuanced and subtle. The word itself contains at least part of the message. It is a term that has travelled. Distinctly Gallic while achieving ubiquity; It has become an allegory for its own meaning.

The word has its origins, or roots, in the French émigrer denoting emigration, or outward movement. The intent in this word is important. The immigrant comes in and the emigrant goes out. Exits. The émigré encapsulates both the centripetal and the centrifugal, they have a place, a gravity with which they are enduringly associated while they persist in moving beyond it, departing, without a clearly defined or scheduled return. The lasting sentiment is that of ‘leaving’. Yet this is disrupted by a lingering of something more, something left to be done.

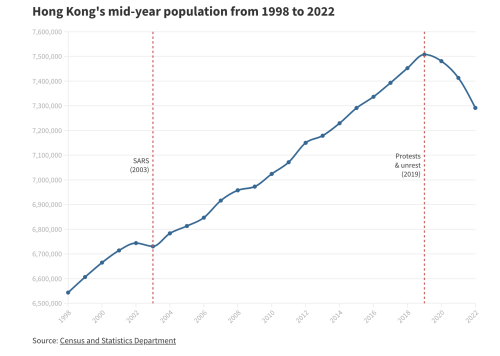

HK exodus of 113,000 residents in a 12 month period.Reports of...

HK exodus of 113,000 residents in a 12 month period.

Reports of the impact of the resident exodus in HK Free Press. In terms of demographics this is building a very interesting picture. Not only are people leaving, but new migrants in appear to be slowing too. Hong Kong’s population is now back to 2014 numbers. Nothing paints a more distinct picture of the recent changes than the graph above.

This accounts for a 1.6% decline in population over a year.

In addition to this report the THE speaks of the falling number of university applications for 2022.

“In 2022, applicant numbers largely based on figures for the city’s eight publicly funded institutions dipped to 39,523 – down from about 64,000 since 2012, Hong Kong’s university admissions body reported.“

August 19, 2022

Skateboarding in Hong Kong with Candy Jacobs, Margie Didal, and Orapan Tongkong.

This is a blast. Sander Hölsgens has gone through some footage dating back to 2019 when we did a University of Skate event at Lingnan University. This footage gives an insight into Candy Jacobs’s trip to Hong Kong and hitting the streets with Margie Didal and Orapan Tongkong. It is especially sweet as Hong Kong and the world itself were very soon to be completely transformed. Every sight and sound conjures up a million memories of life and times in Hong Kong. Footage filmed here at CUHK, Lingnan Uni, Morrison Hill, Queen’s Rd East, Tai Wo Hau, Causeway Bay, 8Five2, and RTHK Radio 3.

Good times, and it is so ace Sander put this edit together.

Skateboarding Chat

Had the pleasure of chatting to Samuel for his postgraduate work in media. He wanted to put together a short film about som characters passionate about skateboarding. We had a chat at Flower Pots in Exeter. The video also includes Henry Matthews, and Adam Hunt.

July 25, 2022

“You can’t be careful on a skateboard”

Skateboarding is notoriously difficult to write about. Iain Borden flags this in the introduction to Richard Gilligan’s work on DIY skateparks, underlining how the visual medium works so much more effectively than the scribed word. Similarly Kyle Beachy crafts a magnetic novel on skateboarding in patiently describing the art while also painstakingly pushing away the cringe that so often creeps in to so many attempts to render the board in literature. Skateboarders are all too familiar with the quick spike of pleasure when a board appears in a film, TV show, or music video. This sudden excitement cools rapidly as we observe the way our precious toy is depicted. It is almost always wrong.

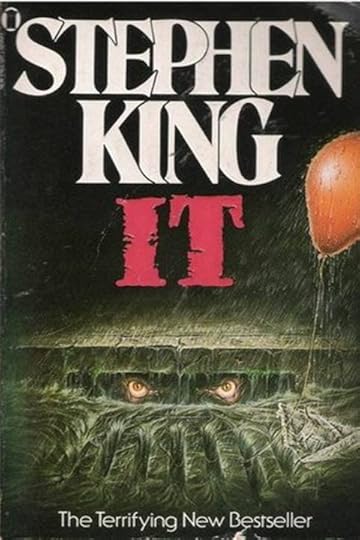

I was therefore taken by surprise at the treatment afforded a skateboard by Stephen King is his now iconic novel IT. Originally published in 1986 the year that Animal Chin was released, the book sits before the modern rise in skateboarding. The boom of vert and well in advance of the heady days of street skateboarding. Yet King taps into both the peculiar and the authentic. Over a few short pages that come just over midway through the hefty text, the central character Bill Denbrough encounters a young boy with a fibreglass board. Stood over the very drain where Bill lost his younger brother to the murderous clown from the id some 30 years prior.

During their brief exchange Bill asks if he can have a go on the young boy’s board.

“The kid looked at him gape-mouthed at first, then laughing. “That’d be funny” he said. “I never saw a grownup on a skateboard.”

This is the first reckoning with time. Back in 1986 adults on skateboards were an amusing rarity. Indeed that prejudice may well linger now. A skateboarding adult may be a source of amusement, but rare they are not. It would be difficult to imagine a 10 year old kid being so bemused by an adult skateboarder in 2022.

The next description is material, sensual, and emotional. Bill handles the board and inspects it before he attempts to ride it.

“He turned one of the skateboard’s scuffed wheels with his finger, liking the speedy ease with which it turned - it sounded like there was about a million ball-bearings in there. It was a good sound. It called up something very old in Bill’s chest. Some desire as warm as want, as lovely as love. he smiled.”

This description resonates. The pleasure in the sound and the way it conjures a feeling of warmth and love, strikes as authentic. Bill appears to be connecting not so much with the joy of skateboarding, but of the skateboard itself. He recognises it as some kind portal to freedom. Or as Lefebvre comments, children’s toys appear to be ‘cosmic’ objects demoted in status some way status.(Critique of Everyday Life Vol1.1991, p 118).

As Bill proceeds to stand on the skateboard he becomes fearful of the practicalities of falling. He imagines a doctor chiding him for attempting to use a skateboard at the age of forty. He imagines that the kid rides the board with no such fear, as an attempt to “beat the devil” like no tomorrow.

He surrenders the skateboard to the kid and gives up on his attempt to ride it. He tells the kid to be careful on the skateboard and gets a more powerful rebuke than the one in the imagined exchange with the doctor.

“Be careful on that,” Bill said.

“You can’t be careful on a skateboard,” the kid replied looking at Bill as if he might be the one with toys in the attic.”

“Right,” Bill said.

He then watches him push away down the hill. This is another evocative passage that I will only repeat in part. It does once again chime with the emotional experience of riding a skateboard and the longing for the freedom of youth.

“But he rode as Bill had suspected he would: with lazy hipshot grace. Bill felt love for the boy, and exhilaration, and a desire to be the boy, along with an almost suffocating fear. The boy rode as if there were no such things as death or getting older. The boy seemed somehow eternal and ineluctable in his khaki Boy Scout shorts and scuffed sneakers, his ankles sockless and quite dirty, his hair flying back behind him.”

The exchange with the skateboarder resolves when Bill stumbles across his old childhood bike ‘Silver’ in a second hand store. Something of the freedom and love expressed toward the skateboard translates to his childhood memories of recklessly speeding through town on this mammoth bike. The two elements of the chapter complement each other sweetly.

In the 2019 film adaptation of the book. IT Chapter 2 the scene is included and is stripped of all emotional content. The young skateboarder no longer has the old fibreglass board but a modern popsicle replete with subtle Overlook Hotel wallpaper graphics. In the film Bill has already found Silver before he encounters the boy and has his moment of rekindled youth riding the bike. Remarkably the film from 2019 gets it all wrong and the book from 1986 get it right. To underline this fact, the skateboard kid in the film become a victim of Pennywise, the boy in the book survives.

July 2, 2022

Andrew Allen FallingI put together this collage of images for a...

Andrew Allen Falling

I put together this collage of images for a short piece on failure Sander Hölsgens and I wrote for Flow Journal.

On reflection it almost looks like I ran Andrew Allen Falling through DALL-E Mini.

July 1, 2022

Books that I have two copies of at home.

1. Sophie’s World - Jostein Gaarder

2. Letters and Papers from Prison - Dietrich Bonhoeffer

3. Northern Lights - Phillip Pullman

4. A Thousand Plateaus - Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

5. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance - Robert M. Pirisg

6. Skateboarding Space and the City - Iain Borden

7. Joe the Barbarian - Grant Morrison

8. Rise of the Robots - Martin Ford (one copy is in Czech)

9. To your Scattered Bodies Go - Phillip José Farmer

10. Skateboarding: Subcultures, Sites and Shifts - Kara Jane Lombard

N.B. I can’t quite explain why there are two copies of these particular titles. It is largely happen-chance with the exception of numbers 6 and 9 where additional copies were deliberately sought. Borden’s I deliberately intended so I had a copy at home and one at the office. Also I have not included my own authored books which also fall under this category.

May 28, 2022

I Shall be ReleasedIt took me two whole weeks to create the...

I Shall be Released

It took me two whole weeks to create the right ambience to sit down and watch Sour III. Truth be told, the right moment never came and feeling a little out of sorts I figured I would give it a shot and try and squeeze it in amidst everything else. The result was a deeply introspective one. I marvelled at the novelty of the skating and drifted off into a meditation about the snug fit between the history of jazz and skateboarding. I tried to position Sour III in this timeline and got lost somewhere between post-bop and free jazz.

The conclusion I have is pretty straightforward and might be of interest to anyone trying to theorise the weird position skateboarding is currently in. Simply put, there are only so many notes in music, and only so many possible variations in what you can do with a skateboard. Please can we surrender the NBDs and instead pursue HIBD. No more ‘never been done’ and instead ‘how it’s been done’, what run up, follow through, and combination. It’s also about the document, who, where, when, angle, pedestrians, roll out… etc. If Jazz is about improvising over standards and reworking conventions, so might be skateboarding. People re-work St Louis Blues and All The Things You Are endlessly. Just as someone continues to outdo the last trick at Hollywood High. Hopefully, we can move on and innovate and keep a healthy relationship with the past. What remains interesting is keeping that tension between familiarity and novelty. Music is about tension and release. I suspect a good part of skateboarding might be too. In crafting a line, we seek to communicate something familiar while pushing the newness to the realms of acceptability. Too safe, too whack, too stiff, and it goes wrong. The tension must be released, otherwise it snaps.

As the final part of the video rolls on to the screen with Simon Isaksson tre-flippin his camera, Bob Dylan starts to play. It’s not the original rendition of the song but the live one by ‘The Band’, a star studded cast. It’s a reworking. Just like the Nina Simone version that Tom Knox skates to in the Isle video Vase. Another Euro video in 4:3 format. Skateboard videos are notoriously formulaic. We expect that and we want that. But we also want the nuance, the difference. Just like Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” we want the familiar in a different face.

In 2022 skateboarding is many things. The best of it is a Palimpsest. A constant reworking of not the new, but the same notes. Perhaps in a different key, a non-chordal note here and there. Building the tension and getting ready to release it.

May 4, 2022

everydayhybridity:Skateboarding and Urban Landscapes in...

Skateboarding and Urban Landscapes in Asia(This is an expanded version of a pre-print book review published in the Asian Journal of Sport, Culture and History)

For a long time I have been lamenting the lack of attention that Asian skateboarding gets. Over the last year it has been recognised in the first ever Asian skateboarding awards. But academic work on Asian skateboarding is harder to come by. Work by Sander Hölsgens and Dwayne Dixon on Korea and Japan respectively, being amongst the most notable, with a few other entries looking at China. Another oversight in academic work has been the lack of in-depth historical attention paid toward skate videos and the wealth of detail they reveal about culture, place, and time. This is precisely why this new book from Urban Sociologist Duncan McDuie-Ra is an exciting addition to academic works on skateboarding. The author focuses on Asian cities and the ways they have been captured in skateboard videos. At the heart of this text is a keen engagement with the ways skateboarders act as cartographers, mapping spots and indexing urban development. The author employs the term shredscape to describe the ways skateboarders construct an understanding of place and argues that the view of cities from skateboard media provides a perspective on urbanism from ‘below the knees’. Seeing the world skateboarders see it remakes and recasts our understanding of Asian cities in dramatic and provocative ways.

In my mind the text acts as a landmark in skateboard academia. The book intentionally avoids explaining the origins of skateboarding, its basic foundations, and the industry itself. Instead McDuie-Ra assumes that readers are already knowing of this or interested enough to be able to figure it out. This points to another coming of age in skateboard academia and one that Iain Borden, Becky Beal, and Ocean Howell can be rightly proud of. Indeed this new text is in constant dialogue with the foundational work on skateboarding and much else. It is also a superb accompaniment to Holly Thorpe’s work on Acton Sport mobilities, showing the ways in which skateboarders have sought out the most remote locations for new and novel spots to skate. Thorpe’s work on post-earthquake New Zealand is also relevant to the ways some of the shredscapes across Asia are entwined with a tragic history.

There is so much to celebrate in this text, the discussion on Shenzhen monasticism describes the bootcamp process of travelling to China throughout the 2000s as a way to amass footage. Hearty discussion on China’s phantom urbanisation and recourse to Charles Lanceplaine’s video of Ordos, the ‘ghost city’ in Inner Mongolia.

There is also a prolonged discussion on Dubai and the We Are Blood (2015) video, noting the special access granted to Ty Evans and the inability for regular skaters to access the same shredscape. I am thankful for the author’s exploration of the bizarre bench session on the helipad of the Burj Al Arab that remains one of the most paradoxical moments in skateboard media.

Other discussion moves us to Abkhazia, Astana (Nur-Sultan), Tehran, India, and Palestine. Much use is made of the videos of Patrik Wallner in his journeys with skateboarders across Europe and Asia. The book is thoroughly engaging and also an accessible read. The author explains how skateboarders are largely disinterested in the politics and history of the places they travel to and employ a different form of appreciation premised on the shredscape. At the same time he identifies that skateboarders are also remarkably adept at indexing development, at reading the symbols of cities in order to understand what spots they might have and how accessible they may be.

In some of the final discussion on India and Palestine there is a recognition that some Asian cities are too peripheral to be placed on the shredscape. This particularly resonated with me as it also connects to the plight of rural skateboarders across the globe who may have limited access to spots on the margins of towns and cities. It also reminded me of skateboarding in a dusty basketball court in Boracay in 2003, perhaps the only skateable spot on the tropical island at the time. Another uneven element of development relates to the Shenzhen shredscape. I recall meeting a skateboarder from Shenzhen in Hong Kong at the Fanling skatepark. He told me that he comes to Hong Kong a couple of times a week. Inverting the typical route of people crossing the border to skate the streets of Shenzhen he travels to Hong Kong so he can skate the skateparks.

In the focus on skateboard videos and the elite pros that have been documented in their travels, the book omits the stories of local skaters. To be fair, this is not the focus of the book. The voices and experiences of Asian skateboarders in locations as diverse as Naypyitaw and Bangalore are still demanding more attention, especially as they lag behind in their ability to construct their own media narratives of their local shredscapes.

So in summary this is a rich and enjoyable book. Well worth a read by anyone following skateboard academia, or Asian urbanism. It will also certainly be of interest to more general skateboard readers. However the book pricetag of £90 (US$ 123 ) will currently limit its readership. Academic publishers of skateboarding texts would do well to recognise the strong interest their publications have amongst certain populations of the skateboarding community, and the paucity of funds to splash out on books rather than decks.

This was written in March of last year. Now the book review has been published I can share it.

May 2, 2022

"Despite its £1m homes overlooking the harbour or Porthmeor Beach, St Ives sadly boasts some of the..."

- https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/st-ives-seaside-theme-park-7017200