Joy Neal Kidney's Blog, page 82

September 30, 2020

Fels-Naptha Laundry Bar Soap

Fels-Naptha heavy duty laundry bar soap has been around since 1893, so there’s a good chance that our grandmothers and great grandmothers used it for “the wash.”

My bar of Fels-Naptha is still in its paper wrapper, but I can get a whiff of the scent. It smells clean and fresh, and remarkably familiar. My own mother may have used it when I was little.

[image error]

Originally created around 1893 by Fels and Company, about the time my grandmother Leora was born, it was the first soap to include naphtha. Naphtha made the soap effective for cleaning laundry and removing the allergen urushiol (also known as benzene solvent), the oil in poison ivy and poison oak, but it was also a cancer risk, so was removed from the soap.

They shaved the yellow bar and added the flakes to the hot water. It was also used as a home remedy to treat poison ivy and other skin irritants.

Now Fels-Naptha is manufactured by and is a trademark of the Dial Corporation.

You can still buy it. It features the old-fashioned paper wrapper and logo.

[image error]

September 28, 2020

Clabe Wilson’s Vehicles

Horse and Buggy

When Clabe Wilson dated Leora Goff, he drove a horse and carriage. Their first date was to a Chautauqua in 1913 at Panora, Iowa.

[image error]Clabe and Leora Wilson, newlyweds in 1914, Panora, Iowa

Clabe picked up Leora from Grandmother Jordan’s at Monteith to spend the day at Dexfield Park near Dexter. They took the horse and buggy, but while it commenced to sprinkle while they were there. The roads were mud so they had to leave in a hurry.

Model T Ford

Clabe bought his first car in 1917, when they lived near Glendon, Iowa, where he worked at the brick and tile plant. They bought it second-hand from a neighbor for some $400.

Clabe had a Model T when they lived SE of Dexter, late 1920s, but I don’t know if it was the same one. Twins Dale and Darlene are on it here.

[image error]

The family, with all seven children, drove to Dexfield Park to enjoy Independence Day 1927.

Driving from Dexter, people encountered Dexfield Hill, the steepest hill in Dallas County. A Model-T filled with people, with its gravity fed gas tank in the back, motored downhill to the park easily. But returning uphill at night was tricky. Sometimes they’d have to back up the hill in reverse, with the headlights shining down the road. It was a wonderful day to get away from the farm and chores and the landlord.

Model T Truck

At some point he got a Model T truck, built about 1923-25. These photos are both from 1929. The first one (oh, how I wish it were plainer), taken in January, shows Donald and Delbert about to go to Des Moines to join the Navy. The brought home a sled for their three younger brothers.

That September, one of the boys thought the truck looked too high, so Clabe took a whack at it with a hammer, stunning them at first. Then they all laughed. He cut down the back of the seat seat and half the windshield. Sports roadster!

Clabe brought home load of coal with it, $3.25/ ton, cheaper than wood that fall. He earned “government wood” instead, a load for a day’s work.

[image error]

1937 Buick

When they moved to a farm near Minburn, Iowa, the Wilsons didn’t have a vehicle. when they were paid as tenant farmers, he and two older sons pooled their money and bought this 1937 Buick.

Germany invaded the USSR the same day the Wilson brothers drove the “smoking” wine-colored Buick to the Des Moines airport for the Air Olympics–Danny, Junior, Delbert, and

[image error]Ready to go to the Air Olympics in Des Moines, June, 1941. Minburn, Iowa.

1942 Plymouth

While Donald Wilson was home in November 1941, AWOL, his family traded off their “old smoking Buick” for a brand-new gray, 1942 Plymouth four-door, 95-horsepower, Special Deluxe sedan with concealed running boards.

[image error]Clabe and Leora Wilson with their Plymouth. Perry, Iowa, spring 1945. There are three wings on Leora’s coat, so Junior had earned his wings. This was when they took Junior to the train the last time, so Clabe drove it home from Des Moines for the first time.

Leora’s Letters: The Story of Love and Loss for an Iowa Family During World War II is available from Amazon in paperback and ebook, also as an audiobook, narrated by Paul Berge.

It’s also the story behind the Wilson brothers featured on the Dallas County Freedom Rock at Minburn, Iowa. All five served. Only two came home.

September 25, 2020

Redfield’s Company “H” 39th Iowa Infantry: Civil War

Colonel James Redfield (1824-1864)

After the call for volunteers came from the White House, James Redfield of Wiscotta, Iowa, became lieutenant colonel of Company H of the 39th Iowa Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. (I’ve read that only single men were accepted as volunteers, but Redfield was a family man, as were Collin Marshall and Elwood Elliott who served with him, and who also lost their lives–see below.)

Redfield was born in New York on March 27, 1824. Iowa still wasn’t a state when Redfield graduated from Yale in 1845, and for a time, served in the office of Secretary of State in New York.

He moved to Iowa in 1855, settling in the town of New Ireland where he purchased a large tract of land with his brother, Luther, and a Mr. Moore. Soon afterward Moore became his father-in-law as he married Achsah Moore on May 7, 1856.

Mr. Redfield and his wife settled in nearby Wiscotta. They had three children–Thomas, Martha, and Mary.

James Redfield served in several capacities in different offices in the county. He was elected an Iowa State Senator from a district which, at that time, consisted of Dallas, Adair, Cass, Guthrie, Audubon, and Shelby Counties. Because the Civil War intervened, Redfield served only one term in the Iowa Senate.

President Lincoln had called for 75,000 volunteers. Iowa’s quota was 950 men, or one regiment of soldiers. Three times that many volunteered on the first Iowa call.

Redfield raised a company of soldiers, most of whom were ex-Hoosiers like himself. He was elected captain and, upon the organization of a regiment, the 39th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, he was elected its lieutenant colonel.

After training, the 39th was sent to Eastern Iowa where they boarded steamboats and headed south to join the fight. Redfield was wounded twice. First he was shot in the foot, then later in the leg, but he refused to leave his post. His life ended soon after when he was shot through the heart during the battle of Allatoona Pass, Georgia on October 5, 1864. Age 40.

Someone wrote about him, “Of rare powers of speech, engaging manners, and cultivated tastes, which gave additional charm to his manly and soldierly character, his death will be deeply mourned by his friends, and will prove a loss to his adopted state.”

Redfield’s body was returned to Dallas County, where he had left a widow and three children. He is buried in the Wiscotta Cemetery, where a Civil War Monument marks his grave. “Founder of yonder town,” is carved on one side of the monument.

A plaque in the Redfield Park commemorates where Company H of the 39th Iowa Volunteer Infantry mustered to head off to war, leaving families behind.

[image error]

Redfield’s widow, Acsah, outlived her husband by 43 years, passing away on June 5, 1907. A gown gifted to Achsah Redfield while her husband was in the legislature is featured in the Redfield Museum.

Lt. Col. Redfield is also remembered on the storyboard that accompanies the Dallas County Freedom Rock at Minburn.

Main source: Cecil E. Charles, Palladium-Item & Sun Telegram, Richmond, Indiana, 1965.

—–

Collin Marshall

Collin Marshall was born in 1826, probably in Wayne County, Indiana, the son of Miles and Martha (Jones) Marshall. He married Sarah June (Sally) Mills, and had moved to Dallas County, Iowa, before the war broke out.

He joined Company H 39th Iowa Infantry at Redfield, Iowa.

[image error]

On July 4, 1863, the 39th Regiment was encamped at Iuka Springs, Mississippi, guarding a corral of cattle destined for the army. Collin’s sister, Minera (Marshall) Thornburg, related the sad news to relatives in Indiana: “I must first tell of the death of Coll. He was shot in the afternoon of the 4th, inst., while riding out about a mile from camp, by a company of Guerillas, some eight or ten in number, who lay hid, then halloed to surrender and fired a volley at the same time, two balls passing through the breast and one through the neck. His horse was wounded also. He raised his hand for them not to shoot, but they only wanted his life.”

Lieutenant Collin Marshall, age 36, was killed at Corinth, Mississippi. They sent to Memphis for a coffin, had his body embalmed, and started it home two days later accompanied by his brother Bob.

Ten days later, Bob arrived in Redfield without the coffin. He got as far as Eddyville, Iowa, eighty miles from home, but there was no freight service from there. He had his brother buried temporarily, then came on alone.

Their older brother, Calvin (Peet) Marshall drove his team and a wagon to Eddyville, returning home seven days later with Collin’s casket. They buried him “in Masonic style” on a hill at Wiscotta, overlooking the town of Redfield.

[image error]

Elwood Elliott

Private Elwood Elliott of Redfield, a native Hoosier, mustered into Company H 39th Iowa Infantry in August 1862, age 30. He was captured by Confederate forces at Corinth, Mississippi, on July 7, 1863. He was taken Belle Island Prison in Richmond, Virginia, where died in the squalor of the camp on December 9, 1863. He is buried at Richmond City, Virginia.

Left a widow, Hannah.

September 23, 2020

Bandstandland: How Dancing Teenagers Took Over America and Dick Clark Took Over Rock & Roll

The Book

[image error]

American Bandstand, one of the longest-running shows in television history, spotlighted well-scrubbed, properly dressed dancing teenagers on every show. They mirrored the show’s perpetually youthful host, Dick Clark, who spun the music Clark often described as the “soundtrack to our lives.”

These are the memories Clark carefully nurtured as he crafted the alternate teen universe of Bandstandland during the formative years of American Bandstand, from 1952 to 1964. Bandstandland was a mythical creation by Clark, who saw the show as a springboard to immense wealth rather than a tribute to teen culture.

Clark was a relentless businessman who once had ownership stakes in 33 corporations, most created by him. He created rules to keep black teens off the show, promoted the teens that danced on the show when it served his purposes and banned them when it didn’t and effectively turned American Bandstand into his own personal infomercial.

Bandstandland sheds light on the little-known backstory of the TV program that was America’s top-rated daytime television show in its heyday and enjoyed a 37-year run from 1952 to 1989.

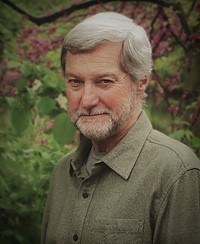

The Author

Larry Lehmer was a newspaper reporter and editor for 40 years, including 24 years at The Des Moines Register. During his time as a senior editor at The Register, the paper was named one of the country’s top 10 newspapers by Time magazine. During his newspaper career, Lehmer was a member of the Society of Professional Journalists and Investigative Reporters & Editors. He is a graduate of the American Press Institute in Washington, D.C., and a former member of the Association of Personal Historians.

Lehmer is also the author of The Day the Music Died: The Last Tour of Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens, which was nominated for the 1997 Gleason Music Book Award. As a result of that book’s success, Lehmer worked with the E! cable television network in producing an episode of its Mysteries and Scandals series, was a contributor to a VH1 documentary on Buddy Holly and was a featured subject on the ID-Discovery Channel’s The Will: Family Secrets Revealed program on Ritchie Valens.

He lives in Urbandale, Iowa, with his wife, Linda.

My Thoughts

This is a very complete story of the American Bandstand years, which were magical to those of us of a certain age. The book covers all the seediness behind the show, and of the greed of the prime movers, including Dick Clark himself.

I enjoyed the innocence and fun of learning the dances on our linoleum floor at home. And teaching a younger cousin to rock and roll in our grandparents’ basement, where was where we cousins ended up during clan get-togethers. I’d forgotten until he reminded me. One wall in next to our bopping was lined with jars of Grandma’s home-canned fruits and vegetables.

September 21, 2020

Wilson Siblings 1927 and 1938

[image error]

[image error]

Junior, Danny, Darlene, Dale, Doris, Donald, Delbert

The first photo was taken in 1927 on Old Creamery Road in Penn Township, south of Dexter, Iowa.

Ages 2, 4, 6, 6, 8, 9, almost 12.

The second was taken on July 4, 1938, when Don was home on leave. Dexter, Iowa.

Ages almost 13, 15, 17, 17, 19, 20, 23.

Leora’s Letters: The Story of Love and Loss for an Iowa Family During World War II is available from Amazon in paperback and ebook, also as an audiobook, narrated by Paul Berge.

It’s also the story behind the Wilson brothers featured on the Dallas County Freedom Rock at Minburn, Iowa. All five served. Only two came home.

September 18, 2020

President Truman and the 1948 National Plowing Match at Dexter, Iowa

Iowa was chosen to host the 1948 National Plowing Match, giving the little town of Dexter nine months to get ready for it. They decided to invite Gov. Dewey to be their main speaker.

He declined.

So they sent a delegation to ask the President if he’d consider coming. He eventually decided to make “whistle stops” in several towns to speak along the Rock Island train route.

The train arrived at the Dexter station about 11:00 the morning of September 19.

[image error]

The Dexter band, led by drum majorette, Thelma Blohm, played “The Iowa Corn Song” for the President, followed by “The Missouri Waltz,” since Truman was from Missouri.

President Truman, his wife Bess, daughter Margaret, and other dignitaries, including Plowing Match princesses, rode in a dozen convertibles, followed by the Dexter band, with the Iowa Highway Patrol last.

President Truman’s convertible was a powder blue Cadillac.

Dexter’s streets had been scrubbed and the main street lined with flags and banners. Store owners decorated their windows to welcome the President.

[image error]

The parade wound north on Marshall Street to the highway, west to the Drew’s Chocolates corner, then north a mile and a half to the Weesner farm, where the contests and conservation and other demonstrations were underway. Cars (including our gray 1939 Chevy with a “city horn” and a louder “country horn”) lined the roads and driveways.

The President was met by ten acres of humanity, estimated at 75,000 and 100,000 people.

The platform awaiting the dignitaries had been built by local World War II veterans who were enrolled in the G.I. night school at Dexter, including John Shepherd, Warren and Willis Neal, Glenn Patience, and Earnest Kopaska.

Truman’s noon speech was carried live over WHO-Radio. (You can watch part of the speech on YouTube, or at the Dexter Museum, which has a display about that historic day, including two of the original tote-boards.

[image error]

I was in the crowd, a four-year-old perched on Dad’s shoulders and told to look at the man on the stage. I didn’t realize until I was older that I’d seen my first U.S. President.

The dignitaries were treated to home cooking in the shade of a tent.

[image error]The tablecloth is signed by President Truman, given to the Dexter Museum by Helen Cook Neal, in memory of her parents, Walter and Leah Cook who were on committees to make the day successful.

We brought our own food and found a picnic spot under a tree. It was a hot day and Aunt Evelyn Wilson had brought a little tub for cousins (ages 2 to 6) to cool off in. Aunt Darlene Scar had brought enough potato salad to share.

I wonder if Governor Dewey wished he had accepted Dexter’s invitation to speak to the crowd assembled that day.

In spite of the blaring headline the day after the election in The Chicago Daily Tribune, “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN,” Truman won!

September 16, 2020

I Remember the Yorktown

The Book

[image error]

A rare glimpse of the horror of warfare is now told through the eyes of a brave and inexperienced young sailor in his memoir, I Remember the Yorktown. In his account of the famous World War II Battle of the Coral Sea, Gene Domienik gives readers an inside glimpse of what it was like on this carrier – the pervading atmosphere, the overconfidence of the crew, the anxiety and fear generated by limited information, and the heroic response of everyone aboard once the call to action came.

The Battle of the Coral Sea is a famous moment in the history of air and seapower. It was a major turning point in World War II, told as only someone who had experienced it could convey. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in World War II, great naval battles of the past, and particularly for sailors and airmen of today.

The Author

[image error]

Gene Domienik joined the Navy at seventeen years of age. He served on two ships, the USS Yorktown and the USS West Virginia. During his Navy career he was awarded The American Theater Ribbon; Asiatic Pacific Ribbon with 7 stars; Philippine Liberation Ribbon with 2 stars; American Defense Ribbon with “A,” and a Good Conduct medal.

My Thoughts

The recollections of a veteran of WWII, who enlisted in the Navy at age 17 and was assigned to the USS Yorktown (CV-5) while it was still on the East Coast. He’d just graduated from Navy Machinist School and served in M Division (main propulsion) on an aircraft carrier which was in combat in the Pacific during the early years of the war–damaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea, and lost in the Battle of Midway.

If you’d like to know what it was like for enlisted men on that very important ship during combat, and even during times between battles, Mr. Domienik’s story certainly reveals those.

I had an uncle on the same ship, so it was fascinating for me.

September 14, 2020

Joyride

Notch-tailed cadets

take turns in the traffic pattern

without benefit of control tower,

sweeping downwind,

shouldering baseleg,

gliding into low approach,

dipping, diving under

a graveled bridge along

Old Creamery Road,

emerging upwind, into

a steep Immelmann turn

against a peach and mauve glow

on September evening,

chattering and fluttering afresh

into the traffic pattern

of young barn swallows,

dark above a flash of rosy tan,

crosswind, downwind,

for yet another spin.

(2006)

September 10, 2020

Clell F. Hoy, a Dexterite Making History and Preserving It

Clell Fletcher Hoy (1917-1991)

Clell Hoy was the stepson of master blacksmith Jim Meister of Dexter, Iowa. About 1930, Jim married Roxie (Stone) Hoy, who had five children: Ora, Cleo, IG, Clell, and Max Hoy. Lyle and Marilyn Frost also lived with them several years.

Clell joined the Navy right after he graduated from Dexter High School in 1936. He served aboard seven destroyers, including the USS Kidd and the USS Madison. During WWII he served at Casablanca in North Africa, as well as in the Pacific–Eniwetok, Okinawa, and the Philippines. He was awarded a Purple Heart. Hoy, a Chief Commissary Steward, served ten years.

After the war, he married Margaret and lived in the Chicago area until her death in 1982. He returned to Dexter and traveled extensively, including to Australia.

Clell Hoy and other family members donated over 1000 homemade tools and other items from the blacksmith shop of his stepfather, Jim Meister. A group of Dexterites bought a small brick building on the town’s main street and moved Meister’s machinery and tools to the building.

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

[image error] [image error]

Hoy willed $50,000 to the Dexter Museum. It has been set up as a trust to help support the museum, which also features the 1933 Bonnie and Clyde shootout in Dexfield Park, the speech by President Truman at the 1948 National Plowing Match at Dexter, as well as items from Jim Meister’s blacksmith shop.

[image error]

Clell F. Hoy is buried in the Dexter Cemetery.

[image error]

Sources: Obituary. Service Record World War II, Dexter and Community.

September 8, 2020

Leora’s Letters: Audio Clip

If you’d like to hear a clip of Paul Berge narrating Leora’s Letters, here it is.

If it doesn’t start right away, click the arrow under the cover.

It was an emotional experience to hear Grandpa Clabe Wilson’s words through Paul’s voice.

Paul also is a flight instructor, writer, and has had his own TV and radio shows. Among other things. Here’s his website.

Featured on Audible today.

[image error]

Leora’s Letters: The Story of Love and Loss for an Iowa Family During World War II is available from Amazon in paperback and ebook, also as an audiobook, narrated by Paul Berge.

It’s also the story behind the Wilson brothers featured on the Dallas County Freedom Rock at Minburn, Iowa. All five served. Only two came home.