Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 27

May 3, 2022

Not In My Torah

I was studying Torah with colleagues on Monday night (May 2) when the news broke that SCOTUS is likely to strike down Roe v. Wade. The sweep of fear and grief across the room was palpable.

In a sense, this isn���t a surprise. We���ve known for a while that this is what the Christian right wants.

It���s still gutting.

On a personal level: I have a uterus. There are 26 states where abortion will become immediately illegal if Roe is struck down. If I lived in one of them, I would instantly lose the right to control my own body.

Because of my preexisting conditions, a pregnancy would likely kill me. If, God forbid, I were raped, I would be forced to carry that pregnancy to term. I have skin in this game.

But in the big picture, this isn���t about me. It���s about countless millions who will suffer when the right to reproductive health care is denied. It���s about human dignity and bodily autonomy and the fundamental betrayal of having our basic human rights taken away...

That's the beginning of a piece I wrote this morning, after hearing the news last night about where SCOTUS seems poised to go. You can read the whole thing at Religion News Service, and I hope that you will: The Christian Right's Abortion Policy Isn't In My Torah.

May 1, 2022

Shine

Scent-memory.

The instant I uncap the bottle, I'm in my twenties again. We used to spend weekends driving around rural New York and Vermont, looking for secondhand furniture at antique stores and junk shops. Even the most weathered, beat-up pieces gleamed again after light sanding and some Murphy's oil soap.

Just in time for the first Rosh Hashanah of married life in our new home, we found a pair of antique wooden church pews. Each featured four folding seats, joined into a bench. It meant that whoever sat on the same side of the table had to work together to push their seats out from the table...

Like this, but with four seats instead of three.

My life has a different shape now. It's almost six years since I moved into this condo. A hand-me-down outdoor table just came my way, and I showed it to my beloved ex when he was here to pick up our son. "You'll want to sand that," he offered. "Use a 220. That way your rag won't catch when you oil it."

Do I have any sandpaper? Of course not. But the local hardware store has plenty, so I picked some up, and a bottle of oil soap. I should have expected the sense-memories that came flooding back. Listening to Car Talk as we drive up Route 22. The scent of oil soap after we bring something home...

Old wood, sanded smooth.

As I sanded and soaped my secondhand outdoor table, I watched robins flit across the grass, pecking between the season's first little yellow flowers. Leaves are coming in. I'm eager for summer, for late long light and sitting at this table watching the changing sky. It feels good to look forward to things.

And it feels good to recognize that these days, remembering my marriage makes me smile. Not unlike how remembering mom (a"h) now makes me smile, though right after her death I mostly felt grief. The sharp edges of loss have been sanded away by time, and now a softer kind of memory can shine.

April 29, 2022

Key

I'd never before made a shlissel challah -- a challah shaped like a key.

Some Ashkenazi Jews have a custom of baking shlissel challah for the Shabbat that comes after Pesach. It's a segulah, an almost magical folk practice: a kind of embodied prayer for parnassah (prosperity).

But why a key? Some teach that God holds the key to our good fortune, so we bake key-shaped challah as a way of asking God for what we need. One of our four new years opportunities is in Nissan -- an auspicious time to ask.

Others cover their shlissel challah in sesame seeds representing the manna that fell to sustain our ancient ancestors during the wilderness wandering after the Exodus. That, too, hints at prosperity.

Or maybe we do this because counting the Omer is a journey through 49 spiritual "gates" and each gate has a key. The shlissel challah represents the key to unlock the next step in the journey toward Torah.

Or because Pesach is meant to instill awe, and the Gemara compares awe to a key, saying: anyone who learns Torah but has no awe of heaven is like a treasurer who doesn't have the key to the door of the bank.

The practice of baking a key-shaped challah turns out to have origins in early Hasidism. Hasidism is the world of ecstatic-devotional practice that began with the Baal Shem Tov, born in Poland in 1698.

One of his students, R. Pinchas Shapiro of Kovitz (b. 1726), taught that during Pesach and shortly thereafter, the gates of heaven are open. This challah focuses our prayers on (re)opening those gates.

R. Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, the Apter Rav (b. 1748), sees this as a mystical prayer to open the "gates of livelihood," as they were opened for our ancient ancestors when the manna stopped falling.

Or maybe it's connected to Song of Songs, which many read during the week of Pesach. Verse 5:2 pleads, "Open for me, my sister." Does this key open a doorway to God -- or into one's deepest room of the heart?

Some press an actual key into the challah and bake it into the bread. I recently brought home a ring full of old keys from my mother's desk, and I briefly considered embedding one in the loaf. (But I didn't.)

I did my best to shape my usual challah dough into a key shape. I always sing Shalom Aleichem while kneading. While shaping, today I sang p'tach libi b'Toratecha -- "open my heart to Your Torah."

And as it began to rise, I sang along with Nava Tehilia's setting of Libi Er. Ani y'shenah v'libi er: kol dodi dofek! "I sleep, but my heart wakes: the voice of my beloved knocks." Or, in my own words (in Texts to the Holy):

Your voice knocks.

Like a magnolia

I open.

Sources for some of the above teachings can be found here and here.

Image: from a google image search.

April 27, 2022

Interpretation

Forgetting where the car is parked

means something important left undone.

The structure deflated like punched dough

means vulnerability and self-blame.

The taxi that makes stop after stop for hours

is the same as the airport with no signs:

what made you think you had any control

over where you're going or when you arrive?

The suitcase that won't hold everything

means the same as the one left behind.

The empty hot tub at the top of the house

is ambiguous, but skylights mean hope.

None of these statements accord with any school of dream (or poem) interpretation I know. I'm also not sure how I feel about placing any single interpretation on a dream or poem. But both are worth holding up to the kaleidoscope, turning them to see what we learn from how the shapes (re)align.

April 24, 2022

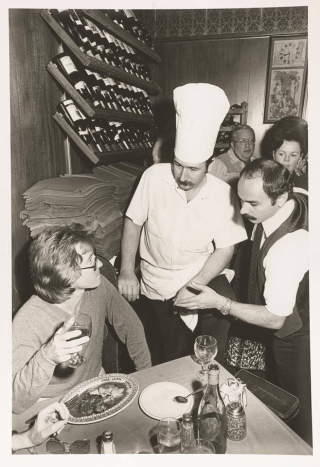

Fine Dining

The Italian place I remember

had dark walls, and candles

in cut-glass red votive bowls.

I thought the owner was Polish.

He and my dad were buddies,

talked business, smoked cigars.

I wore black-patent Mary Janes,

drank Shirley Temples, feasted

on baskets of crusty bolillos:

French bread reimagined

into perfect torpedoes

by Mexican hands.

That's where Dad taught me

how to relish soft-shell crab,

and the names of big wine bottles

like Jeroboam and Methuselah.

All I knew about Methuselah

was that he lived a long time,

maybe forever. I thought

Dad would too.

The restaurant that inspired this poem was the original Paesano's. Here's a reflection on the place written at its 50th anniversary, and here's an oral history from Joe Cosniak. I went to junior high and high school with the daughter of co-owner and chef Nick Pacelli, of blessed memory.

The photograph above came from Vintage San Antonio - A Photo History (FB). Meanwhile, bolillos are a Mexican roll which some trace to the period of French colonization in Mexico. I baked some today. Mine aren't as beautiful as the ones from Paesano's, but they're still pretty good.

Obviously my household of origin didn't keep kosher. I don't eat soft-shell crab anymore, but I remember loving them when I was a kid. Shrimp Paesano, too. Maybe it's just as well: let them be a memory, along with Dad's cigar smoke and the way he laughed with his friends.

April 23, 2022

After (the) Death - Yizkor

We're in a slightly strange position today, spiritually speaking. We are a Reform congregation, and in the Reform world, Pesach is a seven-day festival -- as it is in Israel for Jews of all denominations. Today is no longer Pesach; it's "just" Shabbat, like any other Shabbat.

And yet we're saying the Yizkor memorial prayers today, which is a thing we do at the end of Pesach. We could have held a special service for the seventh day of Pesach and recited Yizkor yesterday, but most of us don't have the practice of taking off work for 7th day chag.

So here we are, preparing for Yizkor even though it isn't Pesach for us. This year, maybe because I am myself a mourner, I noticed something about the confluence of Yizkor and the Torah portion we read today, the first part of Acharei Mot, "After the Death."

The death in question is that of Aaron's two sons, who died after bringing "strange fire" before God. At the moment of their death, Torah tells us, Aaron was silent. Sometimes, loss can steal our ability even to speak. We have no words, because in that moment there are no words to have.

After the death of Aaron's sons, God tells Moses to tell Aaron not to come "at will" into the Holy of Holies, because God's presence there is so powerful that Aaron might die. Instead, Torah outlines a set of practices: here are the garments to wear, the offerings to bring, in order to be safe.

In Torah's paradigm, direct unmediated experience of God is dangerous. (That's why when Moshe asks to see God's glory, God covers him in the cleft of a rock face and passes by, and Moshe only gets to witness the divine Afterimage.) The rituals of sacrifice made contact with God safe.

Grief and loss can overwhelm us, even blow out our regular spiritual circuits. And they're meant to. This is what it means to be human: to love, and to lose. Our tradition's mourning rituals provide structure, telling us when to stay home and when to emerge, and when to give ourselves space to remember.

Reciting the Yizkor prayers four times a year gives a predictable rhythm to the ebb and flow of mourning. The prayers are the same, whether at Yom Kippur or Shemini Atzeret or Pesach or Shavuot, but the way we feel saying them might change over the course of the year -- or from year to year.

A loss that's brand-new can be raw and overwhelming, can steal our words and our breath. A loss that's decades old might feel familiar, more like a broken bone long-ago healed than like a stab wound. Yizkor carries us through from new sharp loss to old familiar recollection.

That shift might take years, and there's no way to rush it. Grief takes the time it takes, and we feel what we feel, and eventually the sharp edges become gentler. Saying Yizkor four times a year is our spiritual technology for plugging in to our losses in community in a way that's safe.

Suddenly it feels exactly right to me that this year's end-of-Pesach Yizkor coincides with reading this first part of Acharei Mot. Like Aaron, we are faced with the question of how to make meaning after loss... and how to feel everything we need to feel while also functioning in the world.

Aaron relied on ritual to safely enter behind the curtain into the place where God's presence was most palpable. And we rely on ritual in our practice of Yizkor, the words we pray as we remember our dead. This too is a kind of going-behind-the-curtain into direct personal encounter.

Even if you don't typically wear a tallit for prayer, I invite you to pick one up as we begin Yizkor. Wrap yourself in it; maybe it feels like an embrace. And when we enter into silence, go behind the curtain of your tallit and take some time to connect with memory and with those whom you've lost.

May our prayers and our song and our silence be a safe container for whatever each of us needs to feel. May this ancient practice hold us up and help us through. And may we emerge from today's encounter with loss and memory feeling present and whole, and sanctified, and not alone.

This is my d'varling from Shabbat morning services at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

April 20, 2022

Four Children

Grief, sometimes

you're the wise child reminding me

you wouldn't even be

at my table if I didn't love.

Sometimes you're the unruly one

insisting life is nothing

but an invitation to loss,

over and over. You sneer

care isn't infinite, only

this sea of salt tears.

Mostly you're the one

who doesn't know how to ask --

or how to answer

when you will depart.

This poem arises out of the haggadah's four paradigmatic children. Shared with gratitude to my fellow Bayit board member and dear friend R. Pamela Gottfried, who remarked to me earlier this week that "Grief is a wayward and rebellious child" -- which sparked this poem.

April 12, 2022

New prayer-poems for the Omer journey

On Saturday night at second seder we'll begin counting the Omer: the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation. Here are seven new prayer-poems for that journey, one for each week -- plus a prayer before counting, and a closing piece that integrates the journey before Shavuot -- from Bayit: Building Jewish: Step by Step / Omer 5782.

This time, seven members of Bayit's Liturgical Arts Working Group wanted to co-create together. So each of us took one week of the Omer. (I got hod, the week of humility and splendor.)

I also wrote an adaptation of a classical prayer before counting the Omer, and we co-wrote a kind of cento, a collaborative poem made (mostly) of lines from our other pieces woven-together, for the end of the journey. You can find all of this (in PDF form, and also as google slides) here at Builders Blog.

Shared with deepest thanks to collaborators and co-creators Trisha Arlin, R. Dara Lithwick, R. Bracha Jaffe, R. David Evan Markus, R. Sonja Keren Pilz, and R. David Zaslow. We hope these new prayer-poems uplift you on your journey toward Sinai.

April 10, 2022

Vintage

I found it in one of my mother's desk drawers. Mostly the drawer contained pens, mechanical pencils, a few thick yellow highlighters. And then there was this little metal case, shaped like a teardrop with a rounded tip. At first I mistook it for a white-out tape dispenser, though Mom hadn't owned an electric typewriter in years. When I pried it open, I found a vintage pitch pipe. The cylinder is silvery (probably made of tin) with a shape like a stylized cloud at one end, engraved with letters representing the chromatic scale. On the back it says MADE IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA. Crafted there, but engraved in English: it must have been made for export. An internet search suggests that these were common in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Did this one come with my grandparents from Prague in 1939? Did Mom pick it up to sing camp songs with her friends in 1950, the year she returned home and told her parents she'd met the man she planned to marry? There's no one left who can tell me its story, but its sound is pure and clear.

Mom and three friends at Camp Bonim, circa 1953. She's second from the left.

Related: Keys

April 8, 2022

Four weeks

I'm fine

except when I'm not.

Four weeks since

the big green tent.

I can't bear to listen

to the saved voicemail.

Most days

I make coffee, pack

my son's lunch for school,

dodge the cold spring raindrops.

Then I remember seder is coming

and you're gone

not here

not anywhere, not even

in that plain wooden casket

that we lowered into the ground.

Minutes go by, sometimes hours

before I shake it off.

How do I get

this postcard to you?

If I light a cigar, will the smoke

reach where you are? Should I

burn this with the hametz

my son will find by candlelight?

Grief rises up,

becomes my spiritual practice.

Like a meditation retreat

it makes my skin thin,

opens my bruised heart.

My mikvah is tears.

If this speaks to you, you might also find comfort in Crossing the Sea and/or in Beside Still Waters.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers