Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 23

November 4, 2022

Whistling in the dark

When the pandemic began here, right after the unveiling of Mom's headstone, I remember feeling an odd sort of gratitude that she was already gone. Her lungs were already compromised. If she'd gotten Covid, she would have wound up on a ventilator. Her death would have been far worse than it was.

When a mob stormed the United States Capitol, I remember feeling deeply grateful that she was already gone -- and that my dad was by then in the grips of some dementia, which meant he wouldn't read about it in the paper, or if he did, he'd forget. They would both have been so horrified.

Today in New York Times headlines, there's this: Between Kanye and the Midterms, the Unsettling Stream of Antisemitism. Surely this is only "news" to people who are not Jewish. My grandparents fled from Hitler in 1939, with my mother in tow. This country was their safe haven. And now...?

For Jews in America, things are tense indeed. Next week���s midterm elections feel to some like a referendum on democracy���s direction. There is a war in Europe. The economy seems to be teetering. It is a perilous time, and perilous times have never been great for Jews.

In some way maybe this makes my rabbinate more like others throughout history. (Aside from, you know, things like my gender.) Was it an anomaly to grow up at a moment when it seemed as though antisemitism were disappearing? I don't want to believe that, but I can't rule out the possibility.

Today it's normal and expected for rabbis and synagogue leaders to enroll in active shooter trainings, so we have a better chance of protecting our communities and perhaps surviving if an antisemite with a gun finds his way into our synagogues. (And it's usually "his.") It's just part of the job.

"This isn't why I went to rabbinical school, but here we are," I joke. "I'm learning a new skill eleven years in!" It's an attempt at a whistle in the dark. My friend and colleague R. Mark Asher Goodman wrote recently, "Should I feel creeping dread about next Tuesday? Is that normal?" I replied, "It is now."

And I thought: living with dread has become normal. Antisemitism continues to rise. Trans lives are under attack. Election denial -- "if we lose, it must have been rigged" -- is rampant. Most Americans believe the founders intended this to be a "Christian nation." These are not "good for the Jews."

A poll by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2021 found that almost a quarter of Republicans agreed that ���the government, media and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child-sex trafficking operation.���

By now we all recognize that as QAnon propaganda, which is deeply antisemitic. We all laughed at "Jewish space lasers" because laughter is a defense mechanism, but as those views become less fringe and more mainstream, it's become harder for many of us to laugh around the clench of panic.

As a child, I used to lie in bed before sleep and think about what I would take if we had to flee in the night. (My diary. A lovey. Could I find a way to save my cat?) That's not particularly healthy, but it seemed normal, at the time. I had read The Diary of Anne Frank more times than I could count.

My mother loved this country fiercely. She believed in the dream of America. And yet she also insisted that every Jew should always have a passport in case we need to flee. I used to tell her she was being paranoid, that would never happen here. I wouldn't say that now. But where would we even go?

Europe is again war-torn. Israel's elections this week returned a right-wing government to power. If this nation isn't safe for us, I'm not sure anywhere really will be. And besides, what about those who don't have the resources to flee? Don't we have an obligation to stand up for them?

"[Our area] is a place people are going to flee to," a local pastor remarked to me a few days ago. "Get that air mattress now." We were talking about the climate crisis at the time. But it might be true for other reasons too. Bodily autonomy. The freedom to practice one's own religion -- or no religion.

I think what I really want to say is, if you're feeling anxious, you are not alone. Meanwhile, having written this, I'm letting it go before I make challah. I can't wait for Shabbat: an opportunity to tune out the anxiety and tune in to something deeper, something that endures even in the worst of times.

October 31, 2022

A new essay in a new parshanut series!

...So does Lech-Lecha mean ���go into yourself,��� or ���go forth from where you are���? Of course the answer is: it���s both.

Because of our calendar, we always read these lines with the Days of Awe reverberating in our souls. And that seems just right to me. The spiritual work of the high holidays takes us on a journey of introspection ��� that���s ���go into yourself.��� Now, as the new Torah cycle gets underway, that introspection fuels ���go forth from where you are,��� a journey of building a better world...

To build an ethic of social justice into our lives and our Judaism, we need to find balance���s sweet spot. We need to journey inward enough to see where we���ve fallen short and what work we need to do. And we need to journey outward enough to take the next action, however small, in lifting each other up ��� pursuing justice ��� mitigating climate crisis ��� helping someone in need...

That's an excerpt from my latest blog post for Bayit: Building Jewish. We've started an ongoing parshanut series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine, and this is my first offering, written for this week's Torah portion, Lech-Lecha. I hope you'll read the whole thing: Journeying Inside and Out.

October 29, 2022

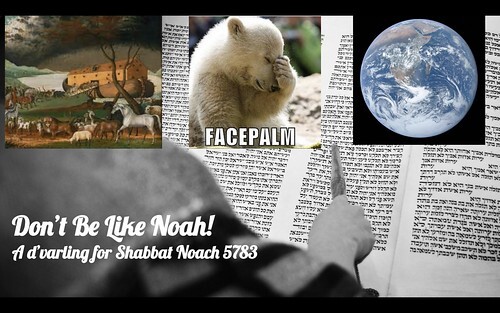

Don't Be Like Noah

Here's the thing I can't get past this year. God tells Noah that the human experiment has failed. Humanity has become corrupt and lawless. So God instructs Noah to build an ark and use it to rescue his own family and all the animals of the earth. And after some description of what the ark is supposed to look like, Torah tells us, "Noah did so; just as God commanded him, so he did."

Why would I have a problem with Noah doing exactly what God told him to do? Imagine a great environmental crisis is coming, and all living beings on Earth are going to perish. So you build a spaceship and you take a genetic seedbank and your own family and you set off into space. But what about all of the other human beings? (And for that matter, the other beings on Earth, too?)

Later in our ancestral story we'll meet Avraham. And God tells Avraham that God plans to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gemorrah. (We'll talk another week about their fundamental sin, which seems to have been a combination of selfishness, violence, and rape.) Hearing this, Avraham argues with God. He bargains: what if I can find you 50 good people? 45? 35? Even 10!

Avraham pleads with God to find a way to spare a couple of towns. In contrast, Noah learns that God is going to wipe out literally every other human being, animal, and plant on the surface of the earth, and he doesn't say a thing. And maybe this is why our sages argue about what Torah means when it says that Noah was a righteous man in his generation. Personally I like Rashi's second theory:

���������������� IN HIS GENERATIONS ��� Some of our Rabbis explain it (this word) to his credit: he was righteous even in his generation; it follows that had he lived in a generation of righteous people he would have been even more righteous owing to the force of good example. Others, however, explain it to his discredit: in comparison with his own generation he was accounted righteous, but had he lived in the generation of Abraham he would have been accounted as of no importance (cf. Sanhedrin 108a).

This may be one reason why we don't consider Noah to be the first Jew, though Noah heard directly from God and followed God's instructions to a T. To be a Jew is to question, to argue, to push back when something is unethical. To be a Jew is to be Yisrael, a Godwrestler -- one who wrestles with the Holy, with our texts and traditions, with what's right and what's wrong: not a silent follower.

To be clear, I don't believe that the climate crisis is a punishment for human wickedness the way Torah says that the Flood was. The climate crisis is the natural consequence of generations of collective human choices made by the industrialized world. We broke it, and we're going to have to fix it. But I do believe that the story of Noach has something to teach us today, to wit: don't be like Noah.

Noah protected his own family. I have empathy for that. It's natural to want to save our own loved ones. But that should be the start of our work, not the whole of it. And I believe that Judaism asks of us much more than that. Torah calls us to pursue justice, literally to chase it or run after it. And in the words of my friend R. Mike Moskowitz, justice can't be for "just us".

R. Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev teaches that that because Noah was so bad at tochecha -- rebuke, as in telling one's fellow human beings that they are acting unethically -- Noah's soul was reincarnated into Moses... who spent most of his life wandering in the wilderness with the children of Israel, grousing at them for being stiff-necked and stubborn, rebuking them every time they made a poor choice!

I love the idea that our souls return to this world as many times as they need, to learn the things they most need to learn. Have you ever heard someone say, "What did I do in my last life to deserve this?" It's a kind of pop culture version of karma. Jewish tradition frames repeated lifetimes not as punishments (e.g. "I screwed up last time so now I gotta do it again") but as opportunities for growth.

What are the qualities we need to strengthen, the patterns we need to shed -- and how can we each use that spiritual curriculum in service of helping each other? Noah could have argued with God, or urged his fellow human beings to make better choices, or helped other people build boats too -- but he built a boat for his own family and the menagerie, and kept to himself. I believe we can do better.

In this era of climate crisis and misinformation, we have to do better. The mitzvah most oft-repeated in Torah is "love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." Torah tells us to feed the hungry, to pay fair wages, to meet the needs of the disempowered. So no, building a boat (or a spaceship) just for us isn't sufficient. Our task is to care about each other -- to care for each other.

And in so doing, together we can build a better world.

This is the d'varling I offered at Shabbat morning services at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog.)

Shared with extra gratitude to the Bayit Board of Directors for Torah study this week.

October 27, 2022

Untitled poem

This hillside is still

copper and rust flecked gold,

the rest bare and barren

a foretaste of what's to come.

Why does this light

still shine

when the rest

have let go?

The leaves aren't hope.

The trees don't mind.

Sometimes it lifts,

the sense of endless loss

and sometimes it settles in

like early winter.

This poem came to me while I was driving. It's not inspired by this specific hillside, but this one is close enough.

I've considered several titles: Fall. Rust. Grief. Let go. To live in this world. (The titles themselves make a small poem.) What would you title it?

October 16, 2022

A mezuzah in time

Today we touch a mezuzah in time.

Behind us: a road glittering with holy days.

Look back over your shoulder and see

a week in the sukkah, and before that

the fierce intimacy of Yom Kippur,

Rosh Hashanah's gilded majesty, and

before that the still waters of Elul,

the grief and uplift of Tisha b'Av...

Ahead: a fallow field scattered with leaves.

Time to integrate our changes.

Shemini Atzeret is a day for pausing,

the silence after the chant.

Today God asks us to linger a little longer.

Seven days of Sukkot have ended, but God says,

"won't you stay in the sukkah with Me

one more day, beloveds?" And we do.

If this speaks to you, you might also enjoy Seven songs, a poem cycle commissioned by Temple Beth El of City Island a few years ago, and A Sestina for Shemini Atzeret.

October 14, 2022

Absurd

Sometimes it feels like we're living in an absurdist novel. "And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed���if all records told the same tale���then the lie passed into history and became truth." (Yep, that's Orwell.) Many today declare lies to be truth. And it's entirely possible that they're succeeding. "I can declassify documents with my mind" is literally absurd, and yet here we are.

Also absurd is the claim that "antifa" was responsible for the January 6 insurrection, when evidence makes abundantly clear that the Capitol was stormed by supporters of the former President and he knew he'd lost. What really worries me is that people who accept "The Big Lie" may be unswayable by evidence, and many of them are avowed Christian nationalists. (That's never good news for us.)

There's a tactic used by domestic abusers known as DARVO: Deny, Accuse, Reverse Victim and Offender. (The term was coined by professor Jennifer J. Freyd.) It feels like an apt description for a lot of what's happening the public sphere lately. Did it begin with the reversal of, "No, you're the puppet"? I'm not the first person to make this comparison, but I've been really struck by it lately.

There is an abusive-bully quality to so many of today's interrelated abuses of power. There's an abusive-bully quality to the authoritarian disdain for diversity. There's an abusive-bully quality to the love of power -- after all, when you're a star, you can do anything to people who have less power than you. And when that's how you treat the disempowered, it makes sense to be afraid of losing power.

Sometimes I wonder how worried we should be that the party of election deniers really admires Viktor Orb��n. Orb��n proudly champions Christian nationalism. Under his rule, Hungary is no longer a democracy. Authoritarian, nativist, homophobic, wants white Christian men to rule -- how awful and regressive. I tell myself that won't happen here. But it may already be happening here.

What does any of this have to do with Judaism, I imagine you asking. Why are you writing about this, rabbi? Because in naming what is, there is agency. Because the only response I can bear is to double down on our values: truth (there's no such thing as alternative facts), diversity and inclusion, care for others (especially for those in need), equity and justice. Even, or especially, if everything falls apart.

I found the image that accompanies this post via a beautiful essay at On Being: The Absurd Courage of Choosing to Live. The image is by Olivier Otelpa, and the essay by Jennifer Michael Hecht is worth reading.

October 13, 2022

Rain

By the edge of the lake

of large red pines

I learned my name

calls out for rejoicing

though it's almost

time to pray

for rain. Beneath

heavy clouds

red-gold flags flutter.

Sometimes watering

looks like weeping

when we're one stiff wind

away from barren.

Teach me

to remove the stone

blocking your lips.

October 6, 2022

After the festival

after Jack Kornfield

After the festival, the laundry.

After the festival, exhaustion

and punch-drunk laughter.

Collapsing into the armchair

and absently petting the cat.

After the festival, silence rings.

There's so much to do -- building

and repair, a new name for God,

making all our promises real.

But not today. Today, gratitude

for the washing machine, swirling

my Yom Kippur whites clean.

October 5, 2022

Balancing Life and Death: Yom Kippur Morning, 5783

Let me take you back to a few short weeks ago, when I was sick with Covid. I was idly poking around Twitter. I was feeling lousy, couldn���t really focus on books or even TV. And then someone I don���t know well posted that she was in shock.

A friend of hers, who���d had Covid a few months prior, had kept a lingering cough from the virus��� and had just died of a pulmonary embolism. Out of the blue. She seemed fine, aside from the cough, for which doctors kept giving her cough syrup and sending her home. But we know that Covid is often associated with surprise blood clots. Boom: pulmonary embolism, and gone.

I responded with Jewish tradition���s usual words of comfort, on autopilot. What I couldn���t help thinking was: wow, Yom Kippur came early this year! I meant, the reminder to take stock of my life and confront mortality.

Yom Kippur is sometimes called a day of rehearsal for our death. We wear white, like our burial shrouds. Many fast from food and drink, like the dead who need nothing. We recite the vidui confessional prayer, as tradition teaches us to do on our deathbeds. And we do big cheshbon ha-nefesh work ��� taking an accounting of our souls. Who have I been? Where did I fall short? If I���m lucky enough to keep living, what do I need to change? If I died tomorrow, what words would I want to have said ��� what amends would I want to have made ��� in order to leave this life with a clean slate?

I don���t expect to die of a surprise pulmonary embolism. But none of us knows how much time we have, Covid or not.

Pirkei Avot (2:15) teaches us to ���Make teshuvah the day before your death.��� But who among us knows when the day of our death will be? Therefore Judaism calls us to make teshuvah everyday. To do the inner work of self-reflection, and the outer work of changing and making amends, all the time.

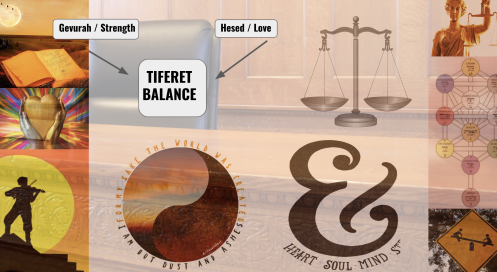

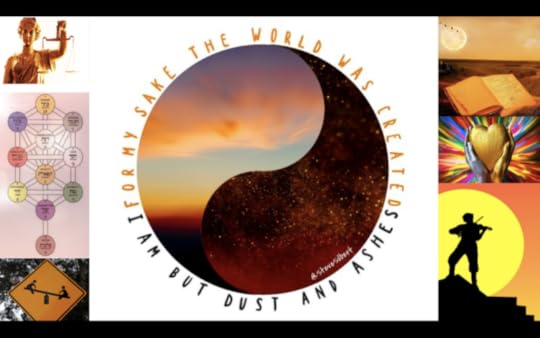

The cards we gave you on Rosh Hashanah read, ���The world was made for me,��� and ���I am dust and ashes.��� Holding both of those truths at once is the quality we call Tiferet, our holy ���and��� of heart-centered balance. (And the theme of this year's Days of Awe.)

These awesome days themselves recapitulate and balance those truths

���The world was made for me��� ��� that���s Rosh Hashanah. Hayom harat olam, ���Today is the birthday of the world!��� On Rosh Hashanah we celebrate the renewal of all creation.

���I am dust and ashes��� ��� that���s today. I am dust and ashes means we are mortal. So what do we want to do with what Mary Oliver calls our ���one wild and precious life���?

At the end of February, my son and I flew to Texas to say goodbye to my dad. He was eighty-seven and already pretty frail, and Covid hit him hard. By the time we flew down, we knew the end was near.

I remember at first being shocked at how much he���d changed. He floated around in time. Words weren���t always available, or they came out scrambled. He was often confused. He opened his mouth to be fed, like a baby bird.

And then I started to notice where my dad���s soul was shining through the fog. He couldn���t always come up with words, but he would look at my son and smile with a glint in his eye, and then tilt his head to the right until my son did the same, and then tilt his head the other way until my son mirrored him, and repeat until they were both laughing. It was like the physical comedy in old silent films. In those moments he couldn���t talk, but he could still tell his grandson a joke.

He had a favorite caregiver, a Black woman named Eddie. Sometimes he was lucid enough to tell me that she had reared ten children and had been through a lot. Other times he said she was his best friend and he���d known her for years. (He hadn���t.)

���This here���s my daughter,��� he rasped to her one day, gesturing at me. ���You know what she does?���

Eddie smiled at him fondly. ���No, what?��� she asked.

There was a momentary pause as he reached for words. Finally he blustered, ���Well, ask her!���

He couldn���t remember what I do for a living. The word ���rabbi��� was missing from his brain. But he remembered that I do something that matters, something worth kvelling about.

���If I weren���t in jail, none of you would be here,��� he said to me one morning. I asked him if he felt like he was in jail, and he shrugged.

At first I thought he meant the assisted living facility, but then I realized: he could have meant his failing body. His body that was giving out on him in so many ways had become his soul���s prison, and he was getting ready to go free.

As they were dying, each of my parents showed something about who they most fundamentally were, deep down, when everything else is stripped away.

With Mom, it was her joie de vivre and her motto, ���make hay while the sun shines.��� With Dad, it was a deep care and sweetness, coupled with that confident glint in his eye. What do we hope will persist in us to the end? What qualities do we hope will shine through?

In the book of Exodus, Moshe asks Pharaoh to let his people go, and Pharaoh repeatedly hardens his heart and says no. At a certain point, the text shifts, and says that God hardens his heart. Which at first blush might seem sort of unfair: why would God do that? Our sages teach: when Pharaoh hardened his heart, over and over, he created that pathway in himself. He carved it deep with his own actions. All God had to do was let Pharaoh be who he already had chosen to be.

With every action, with every choice, we���re making internal pathways. And those paths inform who we are and how we are. If I walk an inner path of trying to cultivate balance, that path becomes well-worn and clear and easier to follow. If I walk an inner path of resentment, that too becomes self-perpetuating after a while.

It���s the spiritual equivalent of the old saying, ���If you keep making that face, you���re going to get stuck that way.��� If we keep making that face, we���re going to get stuck that way. So what face do we want to make in 5783? Okay, I���ve pushed the metaphor too far. But the truth within it stands: who we say we are is irrelevant. What matters is who our actions show us to be.

Dying tends to distill us to our essence, and we don���t get to choose what that essence is ��� except we actually do. We don���t get to pick something that looks nice, like choosing a sweater out of a catalogue ��� ���You know, I���d like my inner essence this year to be pink and happy in the spring, and amber-colored and contemplative in the fall.��� But we do get to make choices, and our regular daily choices will inform who we are and how we respond when push comes to shove.

None of us can control when we die, but we do have some control over who we are in this life. The idea of teshuvah ��� that we can repent, can make amends, can do the work of change ��� means that who we���ve been doesn���t have to be who we���ll become. Balancing who we���ve been and who we���re becoming ��� there���s Tiferet again.

And, there���s no magic short cut. No game hack that gets us a high score we didn���t earn. Anyone can make teshuvah ��� and anyone who wants to make teshuvah has to do the work. And there���s no time like the present. Indeed, some say there���s no time other than the present. Now is all we have.

What changes would we need to make in order to be remembered the way we want to be remembered?

I���m not talking about the kind of new year���s resolutions some of us make on January first ��� ���I want to be bikini-ready by summertime!��� I���m talking about how we treat each other. What character qualities we bring to the fore. How we treat ���the widow, the orphan, and the stranger��� ��� the people most at-risk and vulnerable. (Maybe today it���s the trans kid, the disabled person, and the refugee.) Whether or not we���re doing something to make the world a better place. How we treat the barista or the Stop and Shop employee ��� or that person we don���t like who really gets on our nerves.

Because those are the face we show to the world. No matter what our self-image might be, everyone else experiences us through our actions and choices. And those actions and choices are how we���ll be remembered, when we���re gone.

Earlier this summer a congregant came into my office, and we chatted about one thing and another. And just as she was about to leave, she held up one of the little Life Lights pamphlets from the rack in the back of the room, and she asked me, ���Does Judaism believe in a soul?���

The one-word answer is yes. Yes, Judaism teaches that we have souls, and that while our bodies are temporary, our souls endure.

���No one ever told me that when I was growing up,��� she said. ���Honestly it would���ve sounded goyische.��� As though Christians had a monopoly on spiritual discourse. Y���know what, they���re so focused on ���saving our souls,��� we���ll downplay souls altogether. And in some ways the early Reform movement did that, stripping out a lot of the mystical and supernatural language because it felt outdated, ���Old Country,��� not rational and modern ��� and yeah, maybe too evocative of our proselytizing neighbors.

But Jewish liturgy is full of references to the soul. The choir this morning sang a beautiful setting of �������������� ���������������� ������������������������ �������� ���������������� ��������. ��� ���My God, the soul that You have placed within me is pure!��� Usually the soul is described as something that God gives to us, or guards for us overnight while we are sleeping and returns to us when we wake. Notably, our liturgy insists that our souls are fundamentally pure: no matter how we���ve screwed up, the light of the soul never dims. It just gets a little schmutzed-up by our mistakes, and teshuvah is how we clarify the soul so its light can shine.

Of course, this doesn���t mean that every Jew necessarily believes in an eternal soul or any kind of afterlife to which that soul might journey. ���Two Jews, three opinions,��� as the saying goes. If you���ve never heard this before, or if you don���t believe any of this, that���s okay, you still belong here. Even if you don���t believe in God, you still belong here! (Though remind me to send you R. Brent Spodek���s beautiful I (don���t) believe in God.)

As far as what happens to that soul once the body dies���? I can tell you that I have a book called Jewish Views of the Afterlife, and it���s several inches thick. Over the last 3000 years Judaism has offered many different visions of what might come after this life, ranging from blissful Torah study in the Garden of Eden, to reincarnation when a soul still has work to do or things to learn.

I find all of this endlessly fascinating. And in some ways it���s all beside the point. The question beneath her question was something like: is my beloved still here? I believe the answer is yes.

Many Jews believe that our dead remain accessible to us. Some say we can speak to them as we speak to God. Some say we can ask them for help, or to intercede with heaven on our behalf. Some say we may receive their answers in dreams, or in the world around us. Some say we may feel their presence in the wildlife that graces our path. (Rabbi Pam Wax has an extraordinary poem about that in her book Walking the Labyrinth.) And, of course, the silent Yizkor prayers we���ll say in a moment are a time when many of us go beneath our tallitot and connect with those who are gone.

���I am dust and ashes��� doesn���t mean we���re trash. It means our time is fleeting. So what will we do with it? What do we hope will shine through us to the end? If we knew we were going to die tomorrow, what amends would we rush to make, and what words would we need to say��� and how about doing those things today, every day, so we���re always ready to return to the Source from whence we came?

This is the sermon that I offered on Yom Kippur morning at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog.)

October 4, 2022

Toward Transformation (Or The Holy Atonement Reset Button): Kol Nidre 5783

In the melody of Kol Nidre, I hear aching. I hear yearning. I hear the heartbroken cry of a soul who knows they���ve missed the mark. How the melody descends ��� and descends again ��� and then rises in hope! It���s such a powerful piece of music, I suspect most of us don���t think much about the fact that it���s a setting of��� a legal filing.

In that legal filing, we ask to be released from ���all the vows, promises, and oaths we make with God, the things we say only to regret them, the things we promise and forget, the resolutions we fail to keep.��� We make this request in front of a beit din, a rabbinic court ��� symbolized by the rabbi or cantor flanked with two Torah scrolls. But really we���re making this request in front of the ultimate Judge. The Kadosh Baruch Hu ��� the Holy Blessed One. God on high.

This is not usually my go-to image of God. I like to imagine Shechinah, the immanent, reachable, intimate aspect of God, sitting in my car in bluejeans and listening to me pour out my heart as I drive. I like to connect with God as Creator, as Beloved, as Source of Life. But Kol Nidre invites me into a different kind of dialogue with the sacred. It invites me to open myself to the metaphor of God as source of Justice.

Tonight I imagine God in judicial robes. I can���t quite imagine God���s face ��� the image flickers between every face of every human being who has ever been or ever will be ��� but I imagine an expression at once serious and kind. Both gentle and solemn. Ready to give us the benefit of the doubt, and also able to see right through us to the things we don���t want to admit.

As some of y���all may know, earlier this year I got a summons for jury duty. The jury being selected was for the trial of two men accused of involvement in a fairly high-profile local shooting. When many in the jury pool had been disqualified, the judge called each of us who remained up to the bench for a private conference. Almost all of us in the room were white, as are 87% of Berkshire county residents.

The judge asked me questions like: the defendants in this case are people of color. Would that make it hard for you to be fair and keep an open mind? One of the defendants speaks Spanish and needs an interpreter. Are you inclined to think negatively about him for that reason? Jurors must operate on the presumption of innocence unless proven otherwise. Are you able to do that?

And I thought: I could opt out of jury service by claiming to have bias in one of these ways. But I don���t want to be the kind of person who would do that. So I answered truthfully, and the next three weeks were a rollercoaster.

Witness testimony was sometimes searing in its intensity. Some days I came home and cried. Each day I thought about Pirkei Avot���s injunction to "Give others the benefit of the doubt,��� which is a lot like what the judge told us to do.

It isn���t easy to balance the presumption of innocence and the possibility of guilt. Justice is hard work. It asks us to listen attentively, to root out preconceptions or prejudice, and to approach everything with an open mind. It also asks us to be willing to call things what they are, and to accept that choices have consequences.

That set of instructions makes for pretty good spiritual practice: listening without bias, giving the benefit of the doubt, cultivating empathy and upholding accountability. Our mystics would say, this balances hesed / boundless love, and gevurah / boundaries. God holds these qualities in perfect balance, and we strive to do the same. And what happens when hesed and gevurah are in harmonious balance?

We get this year���s high holiday theme, Tiferet. Balance that lifts us up. Or as we learned on erev Rosh Hashanah, the sacred "and."

We���re supposed to give each other the benefit of the doubt, and uphold accountability. But what about ourselves? I may never know someone else���s heart, but I know my own, if I���m willing to look at it. Tonight we stand before the Judge and ask for our vows to be annulled. For errors bein adam l���Makom, ���between us and our Source��� ��� where we miss the mark in our spiritual practice or our intentions or our hearts ��� God forgives us with hesed, overflowing love. I believe this with all my heart.

But for errors bein adam l���chavero, where we miss the mark in relationship with each other, Yom Kippur does not atone until we do our work.

As Talmud teaches, ���Yom Kippur does not forgive transgressions between people unless they seek forgiveness.��� (Yoma 8:9) Or in the words of Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, ���The holy atonement reset button doesn���t work until we���ve cleaned up our own mess.���

According to Maimonides, a person doesn���t just get to mess up, mumble, ���Sorry,��� and get on with it. They���re not entitled to forgiveness if they haven���t done the work of repair. (And they���re not necessarily entitled to forgiveness even if they have.) Another human being���s suffering is not magically erased because the person who caused it says that they didn���t mean to do it.

This is true in our personal lives, and it���s also true of politicians caught saying racist things, celebrities named as sexual abusers, human resources departments that cover up employee complaints, and governments perpetrating harm against individuals or groups. Fixing damage involves taking specific steps; there���s a process. We can���t ever undo what happened, but we can transform the situation and ourselves.

That���s from her new book On Repentance and Repair. It draws on Judaism���s most enduring text about repentance, Hilchot Teshuvah by Moses Maimonides.

���Another human being���s suffering is not magically erased because the person who caused it says that they didn���t mean to do it.��� I wish we could teach that to everyone. Kindergarteners. Adults. Celebrities. Politicians. Honestly the kindergarteners might have the easiest time internalizing it. The rest of us might get defensive, or deflect, or refuse to recognize that the other person is suffering at all, much less that our own actions caused the suffering.

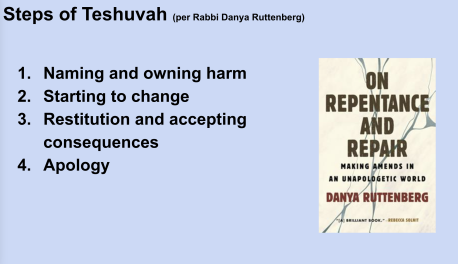

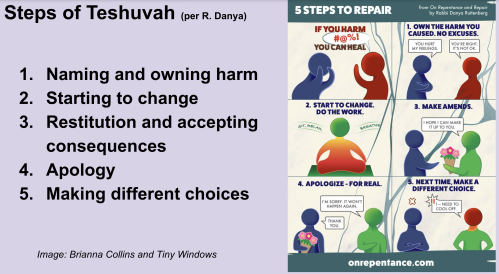

This book applies Rambam���s principles of teshuvah on both a national and a personal scale. There are chapters about harm in the public square, about what national repentance can look like, about what our institutions can and should do. And��� tonight I am focusing closer to home. Kol Nidre is a night for taking an accounting of our own souls. So I want to share R. Ruttenberg���s distillation of teshuvah into five simple steps. Simple, but not easy.

Step one is naming and owning harm. Rambam calls this ���public confession,��� and it���s evoked in our communal Yom Kippur prayers. Those prayers are in the plural ��� ���we���ve abused, we���ve betrayed...��� But often naming and owning harm needs to be in the first person singular. ���I recognize that I did this specific thing that caused harm.��� And it needs to be specific.

If you���re thinking:

I didn���t hurt anyone this year.

Or: every harsh word I spoke was necessary, they deserved it.

Or: it���s not my fault if they felt attacked.

��� stop and notice��� and ask yourself why you can���t bear to see yourself as the bad guy. What parts of your self-image would crack if you had to admit that you had hurt someone?

Remember, ���Another human being���s suffering is not magically erased because the person who caused it says that they didn���t mean to do it.��� Or the person who caused it says, ���I don���t know why you���re so sensitive about this.��� Sometimes we're more comfortable being the victim of harm than owning the fact that we've also caused harm. Because if I'm a victim, then I don't have to do all this work. But if I caused harm to someone, I have a responsibility to name it and own it and try to bring repair.

���Addressing harm,��� R. Ruttenberg writes, ���is possible only when we bravely face the gap between the story we tell about ourselves���the one in which we���re the hero, fighting the good fight, doing our best, behaving responsibly and appropriately in every context���and the reality of our actions.��� Harm happens to all of us, and all of us cause harm sometimes. This doesn���t mean we���re bad people. It means we���re people, full stop. And the reason to do this work is that we want to be people who care about each other, and that includes admitting when we screw up.

Step two is starting to change. She acknowledges that this one can take a long time, and can coexist with the steps that follow. Changing ourselves is not one-and-done, it���s continuing work. And if we don���t deal with our underlying issues, we���ll bring ourselves repeatedly to the same conflicts and flashpoints.

So we need to deal with our ���stuff.��� Our habits, our unconscious patterns, our blind spots. Maybe something in childhood shaped us. Maybe we���re carrying old trauma we haven���t wanted to examine. Like jury duty, this step of teshuvah asks us to notice and root out preconceptions and prejudice that get in the way of seeing clearly. It asks us to look inward and discern why we do the things we do.

This step asks balance between judging ourselves too harshly, and not judging ourselves seriously enough. If we are too harsh with ourselves, we'll be too demoralized to change. And if we're too lenient with ourselves, we'll never have the impetus to become better than we have been.

Step three is restitution and accepting consequences.

If I broke your favorite coffee mug, I have to buy you a new one at least as nice as the old one. If I took money from you, I need to repay it and then some. When it comes to harms like stealing or property damages, this is pretty straightforward. But it���s also true for other kinds of harm ��� emotional harm, reputational harm, psychological harm.

Many harms can never be undone. We still have to make restitution. I think of the Hebrew verb �������� / l���shalem, which means to pay someone, to make restitution, to make them whole, to bring them peace. That's what we're after here: making restitution so significantly that the injured party can feel some peace.

The other piece of this step is accepting consequences. Maybe the person who was harmed draws a boundary and says ���I don���t want to speak to you anymore.��� Or you admit to stealing money out of your parent���s wallet, and they say ���Thank you for coming clean, and also, you���re grounded.��� Accepting consequences is part of teshuvah. This is true on the interpersonal scale of a parent reprimanding a child. It is also true on the much larger scale of celebrities, public figures, and government.

Step four is apology. Notice how far down the list we���ve gone before getting to ���I���m sorry.��� This might seem counterintuitive: if I realize I���ve harmed someone, shouldn���t I apologize right away? But Rambam and Rabbi Ruttenberg say nope. I���ve got to own up to my mistake, start doing my inner work to become a better person, make restitution and accept whatever consequences come my way, and then I can apologize.

I love this because it cuts off the avenue of ���I said I was sorry, what else do you want me to do?��� (Real teshuvah, that's what!) We don���t get to say we���re sorry until we���re well and truly doing the work of trying to change. And, she notes, the apology needs to be genuine: spoken from a place of vulnerability, reflecting real regret and sorrow. ���I���m sorry if you were hurt by this perfectly reasonable thing that I did��� is not an apology.

Step five is making different choices. That���s the biggest one, and the most difficult one. It���s also how we know we���ve actually changed. When we���re met with a similar opportunity to cause harm, and we choose otherwise, repeatedly. ���The goal here isn���t merely making amends,��� Rabbi Ruttenberg writes. ���It���s transformation.���

The goal is becoming a person who wouldn���t do the harmful thing again. That���s real teshuvah: growing into the self we know we could be if we lived up to our highest ideals. Rabbi Ruttenberg writes:

The work of repentance, all the way through, is the work of transformation. It���s the work of facing down false stories and engaging with painful reality. It���s the work of being open to seeing ourselves as we really are���. It���s about figuring out how to be the kind of person who sees others��� suffering and takes responsibility for any role we might have in causing it.

The work of teshuvah asks us to look inward and to make outward changes. (There's that sacred and again.) We need to engage in self-reflection and in taking action to make things right. This balance of introspection and outward action -- there's Tiferet again.

In the criminal trial where I served as a juror, one man was acquitted and the other was found guilty. I wonder whether the one who was acquitted feels like he got a second chance. I wish the man who was convicted could have an opportunity to learn about owning harms, making restitution, offering real apology, starting anew. In his prison sentence I see consequences, but not restitution or repair: not for the family of the boy who was shot, nor for the one who fired the gun. I do believe that repentance is always possible. I don���t think our criminal justice system is designed for transformation.

For mis-steps that harm ourselves and our Source, God is ready to forgive. When our actions or inaction harm others, forgiveness isn���t God���s to grant. The holy atonement reset button won���t work until we do what we can make it right. Whether or not forgiveness happens, this is the work. It might be the work of a lifetime, and that���s okay. It���s better to be doing it than ignoring it. Now is always a good time to start.

I���ll close with one more anecdote from R. Ruttenberg���s book. This comes from Danielle Sered, talking about a young man going through a restorative justice process. She says to him, ���Now that the threat of prison is no longer hanging over your head, are you just going to go back and do the same stuff you used to do?��� And he says, ���Nah.��� She asks why, and he points to his heart and says, ���the judge is in here now.���

May the Judge be in here now, in our hearts, opening us to the work of repentance. May this Yom Kippur strengthen our resolve to clean up our own mess. To practice these steps not just today, but every day. To make teshuvah with humility. To balance inner work and outer transformation. And in that merit, may we be sealed for a good and sweet year.

This is the sermon I offered at Kol Nidre at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog.) Shared with deepest gratitude to R. Danya Ruttenberg for her work, and to all of my advance readers.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers