Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 24

September 26, 2022

Tools for Tough Times: Rosh Hashanah Morning 1, 5783

Last month, the Academy of American Poets shared a Poem of the Day by Joshua Jennifer Espinoza called ���The Sunset and the Purple-Flowered Tree.��� Here���s how it begins:

I talk to a screen who assures me everything is fine.

I am not broken. I am not depressed. I am simply

in touch with the material conditions of my life. It is

the end of the world, and it���s fine...

The poem reminded me of so many of our conversations over the last year. We are not broken. We are simply in touch with the material conditions of our lives.

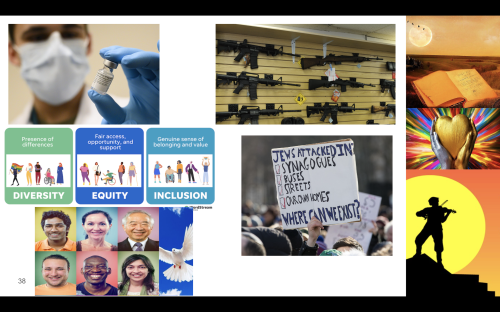

Long Covid continues to mystify doctors. Apparently polio is back. Election denial corrodes our civic life. There are heartbreaking stories out of states where reproductive health care is now banned. And don���t forget school shootings, 29 of them so far this year. And Putin trying to take over Ukraine. And this year has brought a rise in laws designed to abridge the rights of LGBTQIA+ folks, and antisemitism, too.

And then there���s the climate crisis. Floods like the one in Kentucky ��� or in Pakistan, or in Chad. Wildfires (when I wrote this, there were 624 wildfires burning in eighteen states, plus many more around the world.) Extreme heat melting airport runways���

As my friend Rabbi Mike Moskowitz sometimes says, ���the world is super broken.��� I know that many of us are struggling. Some are languishing, living with ���a sense of stagnation and emptiness.��� (per Adam Grant in the New York Times.) And for some of us, languishing can slip into hopelessness.

Our liturgy proclaims: hayom harat olam: today the world is born!

Okay, but how do we celebrate the world���s birthday when things feel so hard?

This is not the first time the Jewish community has lived through collective crisis. The question I���ve been asking is: what spiritual tools did our forebears use to get through hard times? What did Judaism���s toolbox offer them, and what can it offer us?

When Rome destroyed the second Temple, R. Yochanan ben Zakkai asked two of his disciples to smuggle him out of Jerusalem in a coffin. He went to the Roman general Vespasian and asked for permission to build a school in Yavneh. The learning there preserved oral teachings about how we ���did Jewish��� in Temple times. Those became the Mishna, the kernel at the heart of Talmud. In the ashes of the Temple, the sprouts of rabbinic Judaism took root.

Our response to complete destruction was to remember and to learn ��� and in the learning, to begin to design Judaism anew. That���s the first spiritual technology I think of when I think of how Jews have lived through crisis times before. What they did -- remembering what was lost and rethinking what came next -- can help us too. It can lift us out of ourselves, and it can inspire us to build. And maybe those who came before faced something like this, and we can learn from their response.

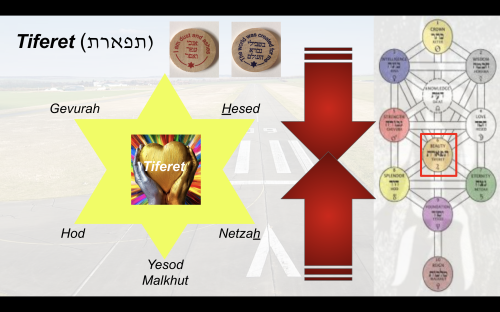

Or maybe their response feels off-key to us, and we can learn from that, too. Either way, notice their balance between remembering what was, and imagining what might yet be. We don���t want a Judaism that drives only with the rearview mirror ��� and we also don���t want a Judaism that ignores the wisdom of our ancestors. Holding what was and what will be in balance: that's Tiferet, this year���s theme for the Days of Awe. (More on that in a moment.)

For spiritual nourishment, my go-to place is the Hasidic masters ��� the rabbis from the 1700s and 1800s who sought spirituality in everything. For others, it might be mussar, texts of ethical self-improvement.

Maybe the learning that nourishes us is secular. I���m trying to learn from my foremothers who marched and agitated for a woman���s right to choose ��� while also learning from Black voices, trans voices, and people of color about how the framework of reproductive justice is more inclusive. I learn about our nation���s history and its present every day from historian Heather Cox Richardson���s Letters From an American, which help me contextualize current events.

And I'm learning about how to face the climate crisis...from scientists who teach that our inner lives have an impact on how we approach our outer lives.

[T]here are bats

Who catch fish

And slime molds that sing

And ancient Greenland sharks

Who don���t even reach sexual maturity

Until they are 150 years old.

This is what I want to say

To those who believe

The Earth is already doomed:

Just look at the capacity

Of this

Gloriously complex planet.

That poem appears at the beginning of Dr. Elin Kelsey���s Hope Matters: Why Changing the Way We Think is Critical to Solving the Environmental Crisis, and it���s a bridge to another spiritual technology I think is core: hope. Historically Jews have hoped ardently for redemption, the coming of the messiah or (in Reform language) the messianic age. Those ideas may feel foreign to us, but the need for hope persists.

So how do we cultivate hope in the face of climate crisis and all the rest?

���To hope is not to wait around until you are feeling optimistic,��� Kelsey writes,���but to join with others in defiant response to what we are doing to the planet. It is an action that you do rather than a feeling that you have.���

As Seamus Heaney wrote, ���Hope is not optimism, which expects things to turn out well, but something rooted in the conviction that there is good worth working for.��� There is good worth working for. Even amidst everything ��� or especially amidst everything. Working toward something better can lift us up. Sometimes we call that tikkun olam ��� repairing the broken world.

We find hope through action, and we take action to help others. None of us can balm all of the world���s hurts ��� but there���s always something we can do for someone somewhere. In order to move beyond despair, we need balance, perspective ��� in a word, Tiferet.

As we said in last night���s d���var, Tiferet is the sacred and: the balance of love and power, head and heart, recognizing that the world is a dumpster fire and that today the world begins anew. It���s the ���and��� of real balance that powers us to change, and to heal the world.

For many of us, focusing locally is a good use of energy. ���Maybe ���rewild��� some of your lawn as we���ve done here, creating more habitat for pollinators and restoring local ecosystems. Or give money or time to Jewish Family Service helping new immigrant families make their homes in the Berkshires.

And if you want to look at a bigger picture, remember that the world���s injustices tend to most impact those who were already most vulnerable, and look for organizations on the ground already doing the work. The Red Cross is helping flood victims in Kentucky. Fair Fight is working to stop voter suppression. The National Council of Jewish Women is helping people access reproductive healthcare.

There are so many ways to contribute to the work of repair. Civic engagement can be an act of repair. Voting. Activism. Tzedakah ��� e.g. giving motivated by justice. You���ll know best what you feel able to do. Listen inside for what tugs at your heart.

I don���t want to minimize. Climate grief is real. The erosion of rights is real, and so are antisemitism, gun violence and more. In the words of the Espinoza poem, these are the ���material conditions of ���life.��� We are all exposed to horrifying events happening around the world daily ��� like the laundry list with which this sermon began. We need to lift each other out of the miasma of grief and languishing.

That���s another of Judaism���s tools for tough times: lifting each other up. Talmud teaches () that a prisoner can���t release themself from jail, and a sick person can���t lift their own spirits on their sickbed. When I was hospitalized over the summer, I learned again how right Talmud is about that!

But it���s not just about that. There are so many ways to live this teaching. Giving words of hope to uplift someone who's feeling hopeless. Helping someone out of an abusive relationship or out of poverty. Helping someone with addiction or depression or an eating disorder. Bearing witness and speaking truth. The work of allyship ��� using our privilege to stand up for others, working against systemic oppressions like racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia.

Lifting each other up requires Tiferet, balance. (This is a literal truth, and also a spiritual one.) It also gives us balance, because it means we're not in this alone.

���Acceptance of what is,��� writes Dr. Kelsey, ���is not the same as fatalism about what comes next.��� Authentic spiritual life asks us to face reality ��� we don���t get to ignore what���s broken. But we don���t stop there. Opening our eyes to what is is the first step toward what will be. That���s another form of balance: holding what is beside what will be.

At the burning bush God says, ���I will be what I will be��� ��� or ���I am becoming what I am becoming.��� Jews find God in change. (If the ���G-word��� doesn���t work for you, try ���meaning��� -- more about that in a moment.)

Judaism is not new to change. Our world has collapsed before. And not just ours! When Europeans came to these shores, our arrival shattered the conceptual and practical world inhabited by Native Americans and First Nations people. Author Rebecca Roanhorse, of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo descent, told the Times, ���We���ve already survived an apocalypse.��� Despite anti-Indian laws and boarding schools designed to strip them of their heritage, Native Americans and First Nations peoples are still here.

And the same is true of the Jewish people. (And of course it is possible to be both Native and Jewish, an inheritor of both of these wisdom traditions.) There���s a lot of apocalyptic talk out there, but I choose to believe that humanity and Judaism will both survive. This isn���t the end. So what will future generations need us to have done? And what will Judaism need to become? Our tradition invites us to find meaning in change, and on the other side of change, too.

Our tradition invites us to find meaning in... pretty much everything. We find meaning, story, and ethical teaching in every part of Torah ��� even in repeated words or the crowns atop the letters! The meaning we find may change as we do, but the fact of finding meaning is constant. That���s another one of our spiritual technologies: finding meaning, or making meaning, no matter what.

As Jews we wrest meaning from our deep library of texts and traditions, and we also search for meaning in the lived Torah of human experience.

Searching for meaning, Victor Frankl wrote, is what sustained him during the Holocaust. And not only him: in the concentration camps, those who searched for meaning had a greater chance of survival. In his words:

Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on. He was soon lost��� . What was really needed was a fundamental change in our attitude toward life. We had to learn ��� that it did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.

We find meaning by asking what life expects from us. What will the future need us to have done? What does Judaism need to become? What can we repair? What can we learn? What actions will help us hope?

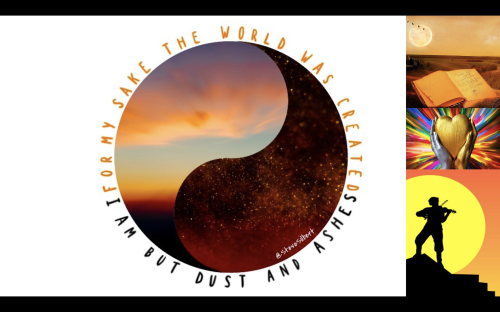

Illustration by Steve Silbert.

Rabbi Simcha Bunim carried two slips of paper in his pockets. One read, ���For my sake was the world created,��� and the other, ���I am dust and ashes.��� When he felt low, he���d look at the teaching from Talmud that says the whole world was made just for us. And when he felt high and mighty, he���d look at Torah���s reminder that everything will die. Our task is holding those two truths in balance ��� holding the whole within which both of these truths reside.

(And to help you in so doing, the card on your chair is for you to take home and carry with you -- courtesy of Steve Silbert and Bayit.)

That story is one of my touchstones��� and to me it exemplifies Tiferet. Tiferet is the whole within which Simcha Bunim���s two truths coexist. Tiferet is balance that lifts us up: not ignoring what���s hard, and also not getting stuck in it. Tiferet invites us to recognize the brokenness and work toward wholeness. Tiferet invites us to see both the world and ourselves with clear eyes: the mistakes we���ve made, and the transformations we could achieve. That we are dust, and that creation was made for us.

In the words of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks z���l, ���[t]o be a Jew is to be an agent of hope in a world serially threatened by despair.��� If you are languishing or feeling despair ��� climate despair, political despair, personal despair ��� you are not alone. Come and find me, and I���ll help you connect with sources of help. Suffering does not earn us spiritual merit points. As our Buddhist friends say: pain is inevitable, but suffering is not.

Come and find me, and I���ll sit on the ground with you in mourning, because I���m there too sometimes. And then together we���ll balance anxiety with agency, and help each other rise. Because to be a Jew is to be an agent of hope, and we reach hope through actions of repair.

In the Passover story, God hears our cry and lifts us out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. We may struggle with that story these days. If God can lift us out, why is our world like this? But Jewish tradition offers us not only that transcendent God, but also divine immanence. Divinity that goes into exile with us, weeps with us, feels with us. God is in our arms and fingers and voices, in every action we take that brings hope.

If you want a Jewish ���app��� for thriving during crisis times ��� what you've just heard are the ones I've got.

And weren���t these always our job? It���s on us to lift each other up, to make meaning, to retell and rebuild and repair. It's on us to recalibrate and rebalance -- to recognize the brokenness and work toward wholeness. It���s on us to remember that there is good worth working for. Especially in times like these.

May opening our eyes to what is be the first step toward what will be.

And may 5783 be a new year of tiferet:

balancing ���I am dust and ashes��� with ���the world was created for me;���

balancing justice with mercy, clear eyes with full hearts, and grief with hope.

This is the sermon that I gave at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires on the first morning of Rosh Hashanah. Offered here with extra gratitude to Steve Silbert for the phone illustration, and to all of my advance readers. Cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog.

September 25, 2022

Erev Rosh Hashanah 5783: The Sacred "And" (co-written with R. David Markus)

���It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.���

The author of these words, Charles Dickens, was a virulent antisemite, and his opening words from A Tale of Two Cities in 1859 England might well describe us on this Erev Rosh Hashanah 5783.

Each year we call Rosh Hashanah a new start, and this Rosh Hashanah falls on troubled times. Science is taming the pandemic, and gun violence is raging. Global living standards are the best ever, and Mississippi���s entire capital city just went days without drinking water while one third of Pakistan was under water. The world is more peaceful than at any time since Charles Dickens, and the Ukraine war threatens global stability.

Genuine commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion are blossoming, and antisemitism is resurging. The U.S. just made historic investments in clean energy, and climate disasters are mounting. Democracy���s guardrails held, and they are at risk.

���It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.���

Both are true. And the both-ness of our ���best of times��� and ���worst of times,��� the emotional and cognitive load of it all, has been a rollercoaster. We���ve felt afraid, courageous, overloaded, numb, sickened, healed, inspired, disgusted, hopeful, helpless, angry, overjoyed and just plain tired ��� sometimes in rapid succession, sometimes all in the same day.

���It was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity.���

We���ve believed and we couldn���t believe it. We had faith and lost it. As a nation, we lost our way and began finding it, whatever our politics or none at all. Routines went out of whack. Our planet went way out of whack.

���It was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.���

Normal went out the window, and hindsight is showing us that for many, normal wasn���t all that. Some recent troubles had been hiding in plain sight. They weren���t news to the poor, marginalized, social justice advocates or scientists. And, much good is happening to offer us real reasons for encouragement and optimism.

Hope and despair; everything before us and ��� sometimes it seems ��� nothing. If it all feels like it might topple over, or maybe we will, or maybe we already did and we���re trying to right ourselves again, then it���s time to seek a new and healthier balance ��� as individuals, as families and communities, as a people, as a polity, and as a planet.

Seeking balance anew ��� in Jewish mysticism, Tiferet. That���s our theme for the High Holy Days of 5783. In a sense, our theme was preordained because our two communities are following a seven-year cycle of Kabbalah. Two years ago, our theme was Hesed ��� qualities of love and kindness that support teshuvah, the path toward our best selves. Last year was Gevurah ��� the strength, courage, discipline and healthy boundaries that make teshuvah possible. On that seven-year cycle, next up was Tiferet anyway ��� and it���s the urgent call of this time.

Balance has eluded us. Usually we feel not its presence but its absence, when we feel imbalanced ��� when something feels off. It���s like our air: usually we see it only when fog or smog rivets our focus.

Yet balance is nature���s goal. Equations balance: it���s what they do. Nature abhors a vacuum and rushes to fill it and restore balance. We all seek balance, though often unconsciously. Our bodies are wired to maintain homeostasis, a chemical and physical balance that we usually notice only if something���s off or we feel shaky on our feet. Relationships, psyches, communities, economies, ecosystems and we ourselves exist in dynamic equilibrium, in or out of balance.

Light and dark, best and worst, tragedies and miracles, me and you. The element common is one little word often overlooked ��� and, Tiferet teaches us, oh so holy.

And that one little word is ���and.���

The world is a dumpster fire, and the world is being made new. Some stuff is badly broken, and some stuff is dazzlingly wonderful. We sinned and must do teshuvah (especially now, in this season), and our souls are existentially pure (even if we forget). Tiferet is our holy ���and��� ��� not to always take a middling view, but to hold and connect whole truths, and often different truths, to boldly enrich our world and make genuine teshuvah possible.

Our world aches for Tiferet now. Problems pile up because, at heart, we lose our ���and.��� Humanity pursued wealth and comfort for centuries as if the ���and��� of environmental impact didn���t exist. Toxic politics can claim that there is no ���and��� ��� no reasonable reason to disagree unless someone is corrupt or stupid. Often our character flaws, our missed marks, pile up because we can���t or won���t fully see the ���and��� of where they came from, how they impact us and others, or that we really can change and make repairs.

And. Balance. They���re easy words to say ��� like ���Love YHVH your God with all your heart, all your soul, all you���ve got,��� or ���Love your neighbor as yourself��� ��� but rarely easy ones to fully live.

And yet, it���s what we���re here for. Biologically we���re wired to seek balance. There���s a reason that ���Fiddler on the Roof��� goes by that title: Jews as a people, and each of us individually, stand atop the roofs of our lives, perched in ways that inherently risk a tumble, trying to keep balance in a world often badly imbalanced. Yet there, exactly there, is where we make beautiful music. We���re all fiddlers on the roof.

So as roof fiddlers, how do we seek balance? How to cultivate this quality of Tiferet and manifest it in our world? That���s our question for these High Holy Days. Maybe our instinctive answer is simply not to move. After all, if we don���t move, then maybe we won���t fall ��� but that���s not balance. That���s being stuck and afraid, a prison of inertia.

Besides, we don���t have the luxury to stay put. Our hearts and souls, our relationships, our country and our planet need change and a healthier balance, not the same old same old. Plus, as any rooftop fiddler knows in our bones, if we don���t move, we can���t make music.

That���s why Tiferet isn���t just balance but also beauty ��� a balance that makes it better, even amidst and through conflict. It���s a holy ���and��� that can harness love and power ��� Hesed and Gevurah ��� to admit the mistakes we made and hurts we caused, and galvanize us to make repairs, however difficult, with a heart of beauty and grace. It���s seeing who we���ve been and who we can become, not just one or the other. It���s feeling the wrongs others did to us and that their souls are sacred. It���s sensing the world in all its brokenness, and our sacred capacity to help heal it. Or as Paul McCartney put it:

Blackbird singing in the dead of night:

Take these broken wings and learn to fly.

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to arise.

Blackbird singing in the dead of night:

Take these sunken eyes and learn to see.

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to be free.

Lots of brokenness, and Rosh Hashanah sings, ���Yes, we can fly, even with broken wings.��� Lots of blindness, and Rosh Hashanah says, ���Yes, we can learn to see again, precisely in the dark.���

Broken and whole. Realism and hope. Tragedies and miracles. Grief and joy. Head and heart. Love and boundaries. Hesed and Gevurah. Rickety roofs and beautiful music. The ���and��� of real balance that powers us to change: that���s Tiferet.

But how? Especially when so much feels out of balance and, for some of us, if we fear that fully feeling it all would unbalance us?

Erev Rosh Hashanah is about limbering up our sense of perspective ��� what we sense, and how we value it. Judaism offers that how we see often shapes what we see, and that the unseen can be more real than the seen. Love isn���t visible, but its presence or absence are very real. The subconscious: invisible, and potent. Values. Ethics. God. Tradition. Identity. Memory. All exert profound influence, but how often do we sense them? Most often, they���re background programs.

Tiferet asks us to deeply sense those background programs, what���s usually unseen. What we can���t or won���t sense, we can���t connect or use for balance. So Tiferet, our holy ���and��� of heart-centered balance, starts with perspective and connection.

So let���s connect. Let���s connect with our sense of things. For instance, let���s connect with this.

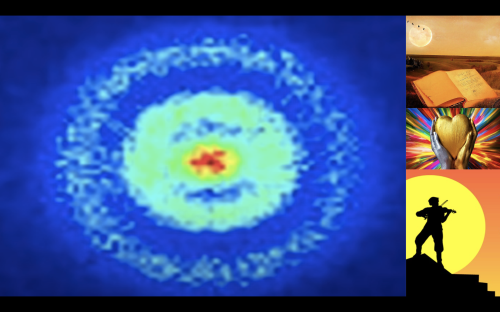

On-screen is the largest structure in the universe, a gigantic supercluster of 830 separate galaxies inside four connected galaxy clusters. It looks a bit like a silken spider web stretching across spacetime. This supercluster is known as the Great Wall of the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey, or BOSS. It is located 13 billion light years from Earth, meaning that its light traveled for 13 billion years to reach us. The BOSS Great Wall superstructure itself is 1 billion light years across, so light from one side takes that long just to reach the other side.

Of course, it���s invisible to our naked eye. As mind-blowingly big as it is, it���s also 1/100,000 the size of a pinhead in the sky. It���s so big, yet so tiny ��� and Rosh Hashanah, Yom Harat Olam, is its birthday.

Now try this.

On-screen is a single hydrogen atom, its one electron sphere and its nucleus of one proton, which in turn combines three subatomic particles called quarks. The diameter of a hydrogen atom is 120 picometers. That means 8.5 billion of them ��� one for each human on Earth ��� would need to stand atop each other to reach the height of the average preschooler.

But wait, there���s something even smaller.

On-screen now isn���t a hydrogen atom but, get this, the shadow cast by a hydrogen atom.

The biggest thing humanity ever saw, and the smallest. The biggest, and the smallest. We���ll toggle back and forth for a moment. Experience what it���s like for you to toggle your vision between both. Maybe type into the chatbox what it���s like for you.

They���re both real, both equally real, seemingly polar opposites, and usually both invisible. The value and perhaps even purpose of all spiritual life is exactly this ��� to refine our vision to the biggest things and smallest things, and help us hold them and calibrate among them. In human terms, this capacity is where Tiferet begins.

It���s time to do likewise with our own selves. Take a moment to look inside, and sense what you���re most proud of. Really: sense your greatest achievement this year. Now sense your worst clunker, the mistake you most regret, the thing that you most wish you could take back. Sense your proudest accomplishment. Your worst failure. Back and forth, both equally real. Type in the chatbox what that���s like.

To be a Jew is to be an ���� (eid) / witness ��� to bear witness to it all, the awe and grandeur of the universe, the often invisible things that are most real and valuable, the brokenness around us and inside that yearns for repair, and the power of the human spirit to do just that. We bear witness not passively, like zoning out to Netflix, but actively, as truth tellers and hope mongers in a world that needs all the truth and hope we can muster.

That���s where Tiferet comes in, and with it our New Year���s journey toward new balance in our lives. It begins right now on this Erev Rosh Hashanah and right here ��� by pushing ourselves to see the best and the worst, in the world and in ourselves. It���s about connecting them, so we can harness our best to repair and even redeem some of our worst. It���s about shining our brightest light into darkness, aware that there is darkness and brokenness: there are wrongs to make right.

Tiferet is about learning anew that, yes, we can calibrate into a new balance, because dynamic balance implies the ability to change. And we can, so long as we believe we can. Reb Nachman of Breslov said, ���If you believe you can destroy, believe that you also can repair.���

That���s why this Rosh Hashanah, this new year, especially calls us into our holy ���and.��� During these ten Days of Awe, we���ll toggle between clear-eyed introspection into our unworthy behaviors, and our confident capacity to better ourselves, to heal, to transform and renew. We���ll connect with a world battered and broken, and full of beauty and blessings, being renewed before our eyes. We���ll feel into how we���ve fallen out of balance, and harness the call of our souls to seek and find balance anew.

That���s our Tiferet journey ahead ��� beautiful and messy, flawed and sacred. It might feel precarious at times, but then again, roofs are always precarious. And that���s where we fiddlers must go!

May the music of this new year 5783 bring sweetness and healing, joy and hope, peace and prosperity, and most of all a new and holy balance ��� to us, to all the people Israel, and to the world. Shanah tovah.

This is the d'var given jointly by R. David Evan Markus of Temple Beth El of City Island and R. Rachel Barenblat of Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires on erev Rosh Hashanah 5783. (Cross-posted to both shuls' websites.)

September 17, 2022

Three days in

1. Thursday

"The second line is really faint," I said. "Maybe I'm imagining it."

"I can see it," said one friend to whom I texted the image.

"It's like a pregnancy test," said another. "You can't be 'a little bit' Covid-positive."

"Take another home test," they suggested. I took another one, a different brand. This one too had the faintest of faint positive lines, if I squinted at it just right.

My kid had been diagnosed with Covid a few days prior. His symptoms were dramatic and immediate. I wore my best KN95 masks indoors, turned the air filter up to high, opened windows... but I knew there was a risk I might come down with it too. I went to the testing center and they swabbed my nose. When the call came, I was already resigned to what I didn't want to be true.

2. Friday

If one is a congregational rabbi, ten days before Rosh Hashanah is not a great time to come down with Covid. (No time is ideal, but this might be the worst time of year to be sick in this line of work.) A flurry of emails set Plan B and Plan C into motion in case they are needed. Plan A is still that I will co-lead services... and I have no way of knowing whether I'll be up to doing so.

"It's Schr��dinger's Rosh Hashanah," I quipped to a friend. Either I'll be up to it, or I won't. Either I'll be recovered, or I won't. Maybe I'll be onsite for Rosh Hashanah, recovered. Maybe I'll be online, still symptomatic. Maybe I'll be in bed. There's no way to know. Dear God: I know that Mystery is a truth of the universe, but did You have to bring that home to me so palpably right now?

Because of my history of strokes and heart attack, my doctor got me in for an infusion of monoclonal antibodies. The infusion center reminded me of my mother. (Back in the early days of her mycobacterial lung infection, they tried treating it with infusions, and I went with her a few times.) A room full of recliner chairs. A television -- on, inevitably. At least it was playing food tv.

To my surprise, there was no IV. Instead a nurse pushed one syringe of the stuff into an IV port on my hand and flushed it with saline. Then they observed me for an hour, taking my vitals every fifteen minutes. I read more of Michael Twitty's new book Koshersoul, which is tremendous, as I expected it to be. Then they sent me home with instructions to rest and hydrate.

3. Saturday

So far my experience of Covid is like a really nasty flu. Unpleasant, but not unlike illnesses I've had before. I know what fever and chills are, and body aches. I know how to get electrolytes into me, and microwave soup, and wrap up in a blanket. To nap when my body asks for sleep. To watch comforting, familiar television that isn't taxing to my tired brain. We all know this drill.

The difference with this one is that sometimes it lingers. And we won't know whether that's my path until it either is, or isn't. Multiple studies have shown that women are more likely than men to develop Long Covid. Some say that resting a lot, during the initial illness phase, helps to forestall it. Clearly rest is important once one has it, if one gets it. I don't want to get it.

I learned this summer that heart attacks often manifest differently in women than in men. Women are 5x more likely than men to have MINOCA, but some (male) doctors have been dismissive of my experience. How many (male) doctors dismiss Long Covid, too, because it impacts women more than it does men? I could rant about medical sexism, if I had the energy. (I don't.)

And, most likely I will be fine. It's a good opportunity to meditate on fragility and mortality. It's also no fun. I'm deeply grateful for vaccines, and boosters, and monoclonal antibodies: none of these was available when the pandemic started. And... I know that not everyone can get the antibodies. Not everyone can take days off from work to rest and heal. I know how lucky I am.

September 14, 2022

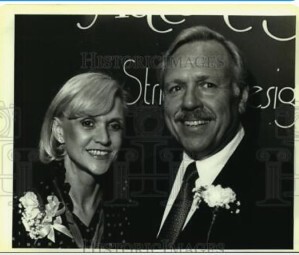

Old photos

Your grandson found photos of you on eBay this morning. They're archival newspaper photos -- from the San Antonio Express-News, or maybe from the San Antonio Light which hasn't existed in decades. It's disconcerting to think of a stranger buying these black-and-white 8 x 10s. Because they have a yen for pictures that give off that 1980 vibe? Because they like the jut of your nose, the spark in your eye? They're "vintage originals." No one knows they're part of my family history. Someone could pick these up for their visual appeal, the way I used to browse for hand-tinted postcards of the Mohawk Trail. When we were cleaning out your house, we recycled all of the yellowed newspaper clippings -- none of us wanted more clutter. You might say, "Who cares, they're just old photos!" But I can't resist these old photographs of you, cropping up in my browser this morning like you're waving hello from olam ha-ba.

Your grandson found photos of you on eBay this morning. They're archival newspaper photos -- from the San Antonio Express-News, or maybe from the San Antonio Light which hasn't existed in decades. It's disconcerting to think of a stranger buying these black-and-white 8 x 10s. Because they have a yen for pictures that give off that 1980 vibe? Because they like the jut of your nose, the spark in your eye? They're "vintage originals." No one knows they're part of my family history. Someone could pick these up for their visual appeal, the way I used to browse for hand-tinted postcards of the Mohawk Trail. When we were cleaning out your house, we recycled all of the yellowed newspaper clippings -- none of us wanted more clutter. You might say, "Who cares, they're just old photos!" But I can't resist these old photographs of you, cropping up in my browser this morning like you're waving hello from olam ha-ba.

September 9, 2022

D'varling for Ki Tetze: Who Do We Choose to Be?

If you look up at the sky this weekend, you might notice that the moon is becoming full. This weekend brings the middle of Elul ��� the final month of the old year; the month that leads us to the Days of Awe. During this month, our mystics say, ���The King is in the Field.���

Here���s the metaphor: imagine that God is a King who lives in a vast and distant palace. Unreachable! So far away! Probably guarded by armies of angels! We���d never get an audience with such a sovereign. But this month, the King is in the field. God leaves that palace and walks with us in the meadow. During Elul, God is right here with us, so close we could almost reach out and touch. ���The King is in the field��� means that God is completely accessible to us. If we open our hearts, we might feel God���s presence, ready to hear whatever we need to say.

Of course, I believe that God is always accessible to us ��� that we can pray whenever and wherever and however we need to, and we will be heard, even if we don���t get an answer. But I love the idea that during this last month of the old year, God is extra available. We might even say, ���Whoa: God is in this place!��� Because every place can be a place of holiness, and justice, and love, a place where we connect with something beyond ourselves. Except we���re human and we keep forgetting. And then we remember again.

Elul is when many of us start thinking about teshuvah again. Teshuvah literally means either ���answer,��� or ���turning around.��� Often it���s translated as repentance or return. Teshuvah can be a year-round practice: noticing our actions and our patterns, checking whether we messed up and need to make amends, doing inner work so we won���t make the same mistakes again. We can do that all the time. Regardless, that work intensifies now, as the holidays approach.

If teshuvah is an answer, what���s the question? I think the question is very simple: who do we choose to be?

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, ���Day by day, what you choose, what you think, and what you do is who you become.��� He lived in the 5th century BCE, around the same time that the Torah was written down in its final form.

He said we become what we choose, what we think, and what we do. My teacher Reb Zalman z���l did say ���the mind is like tofu: it takes on the flavor of whatever you marinate it in.��� Our thoughts definitely can impact us. Then again, Judaism doesn���t generally treat thoughts as sins. We���re much more concerned with choices and actions ��� and their impacts.

This week���s Torah portion, Ki Tetzei, is full of mitzvot ��� commandments. Some of them cry out to be reinterpreted, like the instructions for how to ���marry��� a captive in wartime. Others still ring clear. Here are four that jumped out at me this week:

Don���t abuse someone who works for you. (Deut. 24:14)

Don���t subvert the rights of the stranger or the orphan. (Deut. 24:17)

Leave the gleanings of the fields for the poor, the stranger, the widow, the orphan -- in other words, those at most risk of harm. (Deut. 24:19)

Always remember the story of our enslavement and then our liberation ��� and let that ancestral memory fuel how we treat others. (Deut. 24:22)

What would it look like to live up to these mitzvot? Not abusing our workers. Not subverting or abusing the rights of the vulnerable. Feeding the hungry. Remembering that the Jewish people has known hardship before, and therefore it���s on us to help those who are now in tight straits. Honestly, it sounds like a recipe for a pretty great society, if we can pull it off!

Who do we choose to be? I hope we will choose to be people who do teshuvah: noticing our actions and our patterns, checking whether we messed up and need to make amends, doing inner work so we won���t make the same mistakes again��� and then, from that place of inner transformation, doing what we can to bring repair.

Shabbat shalom.

This is the d'varling I gave at Kabbalat Shabbat services at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog.)

September 5, 2022

Abandon

������������������������ ������������������ ���������������������� ������������������''�� ��������������������������

"Though my father and mother abandon me, God will take me in.��� (Psalm 27:10)

It���s the start of Elul

and these words

stick in my throat.

They���d grown so tired.

I told them it was okay,

they could go. But right now

it isn���t okay. They won���t

ever sit at my table again.

Their voices are silent.

All the high holidays

I haven���t lived yet

stretch ahead of me

without parents,

just still photos

behind the lit candle.

It���s a scant six months

since we buried him

on his side of the bed.

Having no parents

is so much more (or less)

than having only one.

August 30, 2022

A week with the Bayit board

I load my car with my guitar, my computer, tallit and tefillin, giant note pads and brightly-colored markers, a pair of shofarot, and drive north -- for a while. This year's gathering spot for our annual Bayit board retreat is a lakeside cottage by Lac-St.-Pierre, in western Quebec's "cottage country."

We brainstorm. We bring in a few board members via Zoom, though spotty rural internet means sometimes we use speakerphone instead. We sit around with guitars and an occasional ukelele. We enjoy the water, the cricket-song, the calls of ducks (who seem to me to quack ouai, Quebec-style.)

We talk about where the last year has taken us -- books and liturgical arts and a blog and slides for sharing and spiritual games -- and brainstorm what we want to build in the year to come. What tools and systems do people need? What ideas can we incubate, playtest (or praytest), refine, share?

We daven by the lake: sometimes with our feet in the clear water, sometimes in boats, sometimes in the lake joined by darting fish and intrepid ducks. We sing Adon Olam to the tune of "O, Canada." We roast kosher marshmallows over a crackling fire and watch the sparks soar. We laugh a lot.

We talk about Bayit's mission and vision. About books. Ethics. Essays. Liturgy. Art. Music. Games. We talk about the power of convening across difference, and what can flow from that. We study Rav Kook on teshuvah. We talk about Jewish spiritual technologies for getting through difficult times.

We walk down to the dock at night, and lie on our backs, and marvel at more stars than most people ever get to see. We can see the Milky Way stretching out ahead of us. It is spectacular. I think it could entice people who don't normally think about God to think about Mystery and meaning.

We spend an afternoon with human rights activist Michelle Douglas, who ended "the Purge" of LGBTQ+ people in the Canadian army, talking about justice and reparations and repair. We sit with Michelle and a diverse group of local Jewish leaders to talk about justice and the spiritual work of allyship.

We teach each other new melodies. Sometimes the red squirrels chitter along with us or the loons trill in response. We sit on a deck surrounded by cedar and pine forest, and plan Kabbalat Shabbat services for Capital Pride. We talk about building an ethic of social justice, and writers who help us get there.

After board meetings and vision sessions, after roundtable community conversations, after plans and action items, we segue into Shabbes. Harmony and prayer, leisurely learning and music, a "foretaste of the world to come" -- not least because it caps such a sweet a week of preparing to build anew.

Cross-posted to Builders Blog.

August 13, 2022

The Mitzvah: Lessons from Va'etchanan for Now

In this week's Torah portion, Va'etchanan, Moshe continues to recount the major events of the last 40 years. The Torah is approaching its end. Moshe's life is approaching its end. This Jewish year is approaching its end. And before all of those things happen, Moshe gets his swansong -- he gets to give one very long speech on the banks of the Jordan. That's what's happening at this moment in our Torah reading cycle. This week, among other things, Moshe retells the giving of the Ten Commandments.

The giving of the Torah is framed as a covenant, a two-way agreement. Moshe reiterates that that covenant isn't between our ancestors and God -- it's an eternal covenant between God and us, we who are living. The Ten Commandments begin, �������������������� ��������������''�� ����������������������, "I am YHVH your God." They start with a reminder that God is our God -- and wow, there's a question for the ages: what does it mean to say "my God"? How is my relationship with God my own? How is your relationship with God uniquely yours?

The whole verse is, "I am YHVH your God Who brought you out of constriction, out of the house of bondage." (Deut. 5:6) The first commandment, Jewishly speaking, isn't commanding us per se -- it's reminding us. God is our God -- mine, and yours, and yours, and yours. "God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, God of Sarah, God of Rebecca, God of Leah, God of Rachel," as the amidah prayer says. Each of us has a relationship with the Holy. And each of us is brought out of constriction into freedom.

Maybe "the G-word" doesn't speak to you. The Hebrew name YHVH seems to be a unique version of the verb to be, simultaneously implying Was and Is and Will Be, or we might say Being itself -- or, better, Becoming. What does it mean to be in relationship with the force behind becoming, to find holiness in the reality of transformation and change? What does it mean to be in relationship with justice and with lovingkindness -- two of the qualities our tradition says are manifest both in God and in us?

The teacher of my teachers, Reb Zalman z"l, used to quote R. Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev -- "The God you don't believe in, I might not believe in, either." Reb Zalman would've wanted to shift the conversation away from theology -- what we do or don't believe about God -- and instead toward when and how we experience something beyond ourselves. When and how do we experience justice or love or holiness or change? And do we let that experience shape our actions in the world?

In Deuteronomy 6:1, we read:

�������������� ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������������������������������ �������������� �������������� ���������������� ���������������������� ������������������ ����������������

"This is the Instruction -- the chukim and mishpatim -- that your God YHVH has commanded [me] to impart to you..."

Chukim means engraved-commandments. Like the mitzvah of brit milah, which is literally inscribed on some of our bodies. Or the mitzvah of kashrut, Jewish dietary practice. Chukim are mitzvot that operate on levels beyond the rational. And mishpatim means justice-commandments, interpersonal and ethical mitzvot. In context here, this is a big lead-up to whatever Moshe is about to say next. Drumroll please! Whatever Moshe is about to say is core to our tradition, even more than the so-called Big Ten.

The Instruction -- the Mitzvah in question -- is a passage of Torah we call the Sh'ma and V'ahavta. It's part of daily prayer. We recite it when we lie down and when we rise up; we teach it to our generations; we speak about this mitzvah when we are at home, and when we're out in the world. This passage tells us to listen up; to love God with all we've got; to keep reciting these words, learning them and teaching them wherever we are. And, again: whether or not we "believe in God," these words still have power.

I looked to see what some of our meforshim, the classical commentators, said about these words. Rashi (who lived around the year 1100) says that the commandment to "love God" means to do the mitzvot out of a sense of love, rather than out of a sense of fear, e.g. fear of punishment. One who does mitzvot out of love is considered to be at a higher spiritual level than someone who only does mitzvot because they're afraid of what might happen if they don't. It's better to be motivated by love than by fear.

Ibn Ezra says: in antiquity the word lev, heart, also meant mind. For him, the way we love God with all our heart is by always learning, always going deeper into our texts and traditions. And arguably the more Torah we learn, the more mitzvot we'll feel called to do. That's the opinion of the commentator known as the Sforno. He says these verses come to help us recognize that when we love God, we'll take joy in doing mitzvot, because there's nothing better than doing what brings joy to our Beloved.

Okay: so maybe loving God means doing mitzvot out of love instead of fear. And maybe loving God is something we express through learning. And maybe it's about finding joy in doing what's right, because when we do what's right, we bring joy to our Creator. This year, what jumps out at me is the placement of these verses in our seasonal cycle. Rosh Hashanah begins six weeks from tomorrow. Tomorrow in our Reverse Omer journey we'll begin the week of Yesod, which means Foundations or Generations.

What could be more foundational to Judaism than the sh'ma and v'ahavta? We affirm the unity that underpins the universe. Twice a day we remind ourselves to love God, to put these words on our hearts and teach them to our generations and affix them to our doorposts. We use these words to mark our transitions in space (a mezuzah reminds us to pause and notice the sacred when we come and go.) And we use these words to mark our transitions in time: evening and morning, lying down and rising up.

Six weeks before Rosh Hashanah, we reach these verses in our cycle of Torah readings. It's almost if the Torah herself is whispering to us: hey, y'all, the holidays are coming. And maybe we've let our spiritual practices slide, lately. Maybe because it's summer and we're distracted. Or because the world is a Lot, between the news headlines and the climate crisis and monkeypox and whatever else, and we're distracted. Or because we have too much to do and we're distracted. Or we're... just distracted.

This week's Torah portion reminds us:

Stop and breathe.

Listen, and remember the Oneness beneath all things.

Stop to pray the v'ahavta. Cultivate the intention and the ability to love.

Stop to kiss the mezuzah. Be mindful in comings and goings.

Stop to focus on the mitzvot that shape our lives at home and when we're out in the world. The logical mitzvot, and the ones that transcend logic. The spiritual mitzvot and the ethical mitzvot. The ones between us and our Source, and the ones between us and each other.

Take these words, and place them on our hearts. Let them inform the actions of our hands. Let them be a headlamp between our eyes to illuminate our path.

Do these spiritual practices, and teach them to those who come after us, because they are tools to help us through whatever comes.

What if we made a point of that, over these next six weeks? What if we made a point of stretching our spiritual muscles twice a day, every day for the next month and a half? How might that change our experience of Rosh Hashanah, and our experience of the new year that will follow? Spiritual practice doesn't change the cards we're dealt or the world we live in, but it can shift how we experience things. An invitation to give that a try. And in six weeks, you can tell me what kind of difference it makes.

This is the d'varling I offered at Shabbat morning services at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog on our new website.)

August 11, 2022

Womb

At the bend of the river

there's a pond we don't call

the womb of the world, though we could --

this patch of deep water reflecting

tall purple loosestrife.

The pond is a womb, the world

is a womb. Emerge glorious

and dripping, emerge like Chava

radiant and new. Then listen

to cricketsong's rise and fall --

the One Who speaks us into being

the One Who enwombs all creation

is murmuring blessing over

and over, telling us who we are.

August 5, 2022

Who Are We? Lessons from D'varim for Now

"�������������� ������������������������ �������������� ���������������� �������������� �������������������������������������� ������������������ ���������������������������"

"These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel on the other side of the Jordan..." (Deut. 1:1)

Photograph by Munir Alawi, 1839: the banks of the Jordan.

These are the opening words of this week's Torah portion, and the opening words of the book of D'varim, Deuteronomy. Deuteronomy is the last of the Five Books. If we're starting Deuteronomy, then the Days of Awe must be just around the corner.

(They are.)

This is the moment in our ancestral story when we pause and take stock. The children of Israel have been wandering in the wilderness for forty years -- in Torah's language, a lifetime.

So we encamp by the river, and Moshe tells the story of the wilderness wandering. He's speaking to the generation born in the wilderness -- those who experienced the Exodus are now gone. When he's done retelling the story, he will cross over into whatever comes after this life. The people will cross over into the next chapter of their journey. And we will cross over into 5783, a new year full of unknowns.

For Moshe and the children of Israel, this is a moment to pause and take stock of where we've been, who we've been, and what we want to carry forward. Of course, the same is true for us every year when we reach this point in our story.

It's a little bit like the moment in Disney's cartoon Amphibia where the protagonist Anne looks at the blank page inscribed, "Who am I?"

Asking the question of herself helps her realize that she chooses to be someone who does the right thing. As Jews, we ask ourselves that question all the time. Some of us nightly before the bedtime shema. Some of us weekly, before Shabbat. All of us annually, before the Days of Awe. Which is to say... now.

In the midst of this, here comes Moshe in this week's Torah portion, retelling the story of the scouts.

Remember Shlach? The giant grapes? Mirror illustration by Steve Silbert.

Remember, twelve men went into the Land. They retrieved giant grapes. They said they felt like grasshoppers compared to the giants they saw there. When they came back, ten of them said "we can't do this," and only two said "sure we can." And the people believed the ten who despaired.

So God said, if the people don't have faith, they won't enter the land. This whole generation that knew slavery is going to die in the wilderness, except for Joshua and Caleb.

Moshe tells that story more or less the way we heard it the first time. But he makes one significant change. "Because of you," he says, "������''�� was incensed with me too, saying: You shall not enter it either."

Hold up. That's not the reason Torah gave for why Moshe won't enter the land!

An artist's rendering of what actually kept Moshe out of the Land of Promise.

God makes that call when Moshe angrily hits a rock to make it produce water, instead of speaking to it as God instructed him. We might quibble with that decision-making. Was it really fair for God to punish Moshe that much for one moment of anger? But fair or not, that's definitely how the story went.

And now Moshe's changing it up. He's conveniently forgetting that the reason he won't live to enter the Land is because he chose violence instead of speech. It's because of his own actions and choices -- not because the people lost faith.

As our ancestral story pauses on the banks of the Jordan, we're at the edge of a new year. Because it's human nature, maybe we're tempted to do what Moshe just did: to retell the story of the last year in a way that avoids taking responsibility.

Where do we want to pretend away our own poor choices? How often do we want to say, "it's their fault," pointing a finger at someone else because that feels more comfortable than admitting that we messed up?

It's okay to feel the impulse to do what Moshe did. It's not okay to actually follow in his footsteps here. Our spiritual tradition asks us to do better than that.

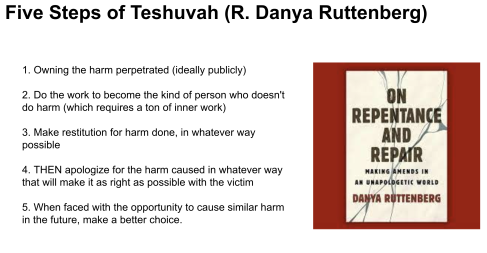

This is the inner work of teshuvah -- repentance; return; turning our lives around. Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg writes that there are five specific steps to repentance work:

(I can't wait for her new book on this subject, On Repentance and Repair, due just before Rosh Hashanah.)

Unfortunately we don't get to see Moshe doing this kind of repentance work. He blames his misfortune on somebody else -- the scouts who brought back a negative report. Tradition teaches that the scouts returned with that negative report on Tisha b'Av, which begins tonight -- though it's Shabbat, so we'll observe the day on Sunday instead.

Tisha b'Av is a day of mourning. In addition to being the anniversary of the scouts' screw-up, Tisha b'Av is the date when Babylon destroyed the first Temple, the date when Rome destroyed the second Temple, the date when the first Crusade began in 1096. Also the date of many other tragedies visited on the Jewish people through our history.

Tradition also teaches that the 9th of Av is the day when moshiach will be born -- the messiah, redemption, ultimate hope, or maybe the age or era when the work of healing creation will be complete. It's as though recognizing that wow, the world is really broken can be the first step toward repair.

(It can.)

On Sunday we'll take first steps toward the repair inherent in a new year, full of new possibility. We'll begin the reverse Omer count -- 49 days until Rosh Hashanah. In the spring, after Pesach, we count seven weeks of the Omer as we prepare ourselves to receive Torah anew at Sinai on Shavuot. Now, as fall approaches, we count seven weeks as we prepare ourselves to enter a new year.

So much has happened in the last year that it may feel like a lifetime.

Who have we been, over the lifetime of the last year? When were we hopeful, and when did we despair? What do we feel proud of, and what do we wish we could pretend never happened (or wish we could blame on someone else)? What's the inner work we need to do, in order to do the outer relational and healing work that others can see?

Rosh Hashanah begins seven weeks from Sunday night. Who have we been this year, and who will we choose to become?

This is the d'varling that Rabbi Rachel offered at Kabbalat Shabbat services at Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires (cross-posted to the From the Rabbi blog at the new CBI website.)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers