Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 30

January 18, 2022

Tending

I tend a botanical garden.

Here jungle trees stretch

tall as I can see, dripping

with trailing lianas

that dip into still pools.

Over there, soft dark podzol,

topped with towering taiga spruce.

In between: a small field

of sunflowers lifting

bright faces to the sky.

I've started keeping bees.

I watch them dance from flower

to flower, then meander dizzy

back to their hives. Honey jars

line up like amber trophies.

In my son's Minecraft world

there is no pandemic.

No one spits at nurses

or lies about elections.

No one's father has dementia.

My son thinks I'm playing

for his sake. I build

shul after shul, and in each

I pray for a world

where evil vanishes like smoke

like the mumbling zombies

who go up in flames

every time the blocky sun rises,

gilding the open hills

and endless oceans with light.

January 11, 2022

The well

It's not that the well's run dry.

The walk feels too far. It's uphill

in the snow both ways, and

who has the strength to carry

those dangling buckets balanced

on their shoulders now? I'll stay

on this secondhand chair, wrapped

in my mother's holey shawl.

Make another cup of tea, stay quiet.

Grief sits with me by the fire.

Out the window, tiny birds track

hieroglyphics across the icy ground.

Originally this poem had a couplet about the 5.49 million COVID deaths worldwide (so far.) I removed it; it feels too direct, it belongs in an essay and not a poem. But as a Jew I'm always mindful of the number 6,000,000, and it's horrifying that we're creeping up on that number of COVID deaths. All of which is to say: if grief is your companion by the fire these days, you are not alone.

January 8, 2022

From smallness to hope: a d'varling for Bo

In this week's Torah portion, Bo, we are deep in the story of the plagues and traumas that unfolded as a prelude to yetziat Mitzrayim, our Exodus or going-forth from the Narrow Place.

The Hasidic master known as the Me'or Eynayim teaches that our spiritual ancestors were so overwhelmed by the hardship and servitude of Mitzrayim that they lost ������ / da'at, knowledge or awareness of God.

Part of what was so painful about Mitzrayim, he says, is that we lost access to our spiritual practices and our traditions. Maybe we had a vague sense that those things had meant something to our ancestors, but we weren't living them. So our awareness of God atrophied like an unused muscle.

When we were in Mitzrayim, says the Me'or Eynayim, our ������ / da'at (awareness) was ���������� / in galut (exile) and ������������ / in katnut (smallness). Our awareness of God went into exile, our awareness of God became diminished. And then he says something that really leapt out at me, reading it this year: it's as though God says to us, �������������� ������������ -- "I made Myself small in Mitzrayim."

As though when our lives contracted, God's own self contracted too. When we are in Mitzrayim, it is as though God shrinks. When we are in tight straits, when our hearts and souls feel constricted, when our lives feel constricted, it's as though God becomes smaller. When our awareness of God atrophies, it's as though God actually shrinks. Wow: this year, that teaching really speaks to me.

There's a website called What Day Of March 2020, and if you go there, it will tell you that today is the 680th day of March 2020. As though time stopped when the pandemic began for us, and that month of March has lasted forever. It's a joke, and it's also not a joke.

Between the Delta variant and the Omicron variant, earlier this week there were more than a million new COVID cases. We're facing our third pandemic Purim, our third pandemic Pesach. Hospitals everywhere are filling up again. We are all tired of this. And it is nowhere near over yet.

Right now the pandemic is our Mitzrayim. These are some tight straits. Maybe our hearts and souls feel constricted. Maybe we're exhausted or overwhelmed or afraid. And when we are in tight straits it's natural for our awareness of God, our sense of where we fit into the Mystery of the cosmos, our capacity to hope to become diminished. For us as for our ancestors, it's as though God becomes smaller.

That could also be a description of what it feels like to grapple with depression. Awareness of God diminishes, capacity to hope diminishes, connectedness to what sustains us diminishes, sense of Mystery diminishes -- it's as though God becomes smaller. This teaching resonates on that level, too... though this isn't just a time of personal Mitzrayim, it's a time of communal Mitzrayim.

This week's Torah portion, and this commentary from the Me'or Eynayim, arrive at just the right time. They're here to remind us that even when we feel like we're in galut in Mitzrayim, exiled in these tight straits, our spiritual task is to trust in yetziat Mitzrayim, to trust in the Exodus. Our work is to cultivate our capacity to feel in our bones that life will not always be like this. That's a big leap of faith.

I think it's a necessary one, if we want to get through this pandemic spiritually intact. Our work is to strengthen our da'at, our awareness of God. If the "G-word" doesn't work for you, try: our awareness of hope, of love, of genuine justice. Because when we strengthen our da'at, we strengthen our capacity not only to trust that better days will come, but also to work toward those better days together.

Offered with endless gratitude to my hevre at Bayit, with whom I'm studying the Me'or Eynayim.

This is the d'varling I offered at Shabbat morning services this week, cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

January 4, 2022

A poetry reading and conversation about grief - on Zoom - on January 9

Love poetry? Experienced the loss of a loved one? Join a Zoom conversation (at 7:30pm ET on Sunday, January 9) with two poet-rabbis about how we used poetry to navigate the grief of a loved one.

The evening will feature Rabbi Pam Wax, author of Walking the Labyrinth, and Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, author of Crossing the Sea , in a conversation about poetry and grief work moderated by Rabbi Nancy Flam, a pioneer in the field of Jewish healing and contemporary spirituality. Hear poems from both books, along with conversation about grief work, poetry, and prayer.

RSVP for Zoom link to cbinadams at gmail dot com.

January 3, 2022

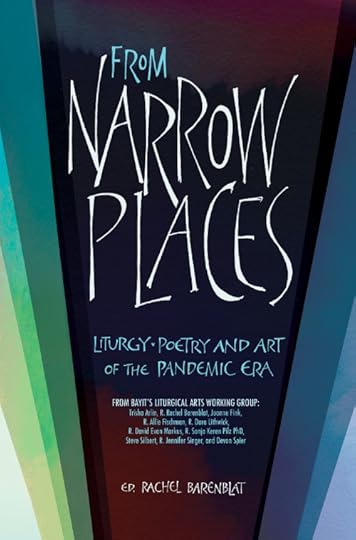

Announcing From Narrow Places

Co-creating new liturgy for these difficult times is one of the things that has brought me spiritual sustenance over the last eighteen months. I'm honored to have convened this extraordinary group of artists, liturgists, and poets, rabbis and laypeople alike, and I'm humbled by the knowledge that our work has uplifted hearts and souls in many places.

I hope you'll pick up a copy of this book, and I hope that what's in it will sustain you.

Now available for $18 -- From Narrow Places: liturgy, poetry and art of the pandemic era from Bayit's Liturgical Arts Working Group. Featuring work by Trisha Arlin, R. Rachel Barenblat, Joanne Fink, R. Allie Fischman, R. Dara Lithwick, R. David Evan Markus, R. Sonja Keren Pilz PhD, Steve Silbert, R. Jennifer Singer, and Devon Spier.

Rabbi Irwin Kula, co-president of CLAL, writes,

For too many, prayer is a vending machine experience and so unsurprisingly it no longer works. And then there are the poets and liturgists in this heart opening collection From Narrow Places who know prayer is a powerful way of consciously surrendering to the mystery and exquisite bittersweetness of Life. This collection of prayers will inspire and enchant you ��� the real job prayer is supposed to get done.

And Rabbi Vanessa Ochs, professor at University of Virginia and author of Inventing Jewish Ritual, writes,

From Narrow Places gives language and imagery to the Jewish spiritual creativity that is still holding us up through the pandemic. I pray that speedily in our days we will look back at this volume as a testimony to how Jews of one era weathered a crisis and emerged even stronger. For now, it chronicles how the richness of Jewish living, full and fluid, is holding us up in these challenging days. I will confess: each page unlocked doors to my unexamined disappointments, sorrows and even deep joys. Many tears, but good ones.

Available now for $18.

December 21, 2021

Solstice

Shortest day of the year.

All the clocks are wrong.

Overhead is a dull seashell.

Clouds cover the sun.

I have to trust

what I can't see.

And my heart --

a worried compass needle

yearning

for your light.

December 17, 2021

The ones who come after: Vayechi

This week's parsha is Vayechi, "He lived." It opens, "Jacob lived seventeen years in the land of Egypt, so that the span of Jacob���s life came to one hundred and forty-seven years." (Genesis 47:28) As with Chayyei Sarah ("The Life of Sarah") earlier in Genesis, this parsha named after someone's life is actually about their death, because only at the end of a life can its wholeness be measured.

Joseph brings his sons to their grandfather's bed, and Jacob asks, "Who are they?" Maybe he doesn't recognize them. Maybe he knows they're related to him, but just can't recall their names. Joseph says, "these are my sons, whom God has given me here." I like to imagine that his voice and demeanor are gentle. It's okay that you don't remember; I can tell you who they are.

I learned the term "benign senescent forgetfulness" from John Jerome z"l in his book On Turning Sixty-Five: Notes from the Field. As a writer and a runner he was fascinated by the effects of aging on body and mind. Benign senescent forgetfulness is the natural tendency of the human brain to start losing track of things. It's normal. As we age, some of what's in our brain just... falls out.

Of course, memory loss can become disabling. I wonder how Jacob handled his inability to remember his grandsons. Did he get frustrated by the mental holes where knowledge used to be? More broadly: could he take comfort in memories of his wives and children, his travels and adventures -- or did disappointments and losses take center stage as other memories slipped away?

Sometimes memory loss sparks paranoia. Because the world doesn't feel right, and words and memories aren't within reach, elders with dementia often lash out at their children or caregivers. That came to mind this year when I read Jacob's parting words for each of his sons. Some of those words are loving and kind; I like reading those. But some of his words seem belligerent, even cruel.

In Jacob's case, given what we know of his children's lives, some of his anger may be justified. For instance, he accuses Shimon and Levi of violence. I can understand where that's coming from, because they did make violent choices. He intimates that Reuben encroached on Jacob's marriage bed with Bilhah, which may be supported in Torah - though some commentators disagree.

What jumps out at me is how common that accusation is. My grandfather z"l levied a similar accusation near the end of his life. (Women often accuse their children or caregivers of stealing their things.) We all knew it wasn't true; it was dementia clouding his mind. But it's still painful to hear words like those, especially from someone who had previously been generous of spirit.

This year I wonder: how did Jacob's deathbed words land with his grown children? Did they find any comfort in the knowledge that some of these words might have been rooted in dementia? And is it fair to blame the curses on dementia while holding on to the blessings that accompanied them? Because some of what Jacob says at the end of his life is gentle and tender!

He compares Judah to a mighty lion; Naftali to a beautiful deer; Joseph to a colt strengthened by God. And to his grandsons Ephraim and Menashe he offers a poignant blessing, saying, "May the angel who keeps me from harm bless the ones who come after!" (That's R. Irwin Keller's singable translation.) And then Jacob pleads, "In their name, may my name be recalled." (Genesis 48:16)

You may recall that he had two names: Ya'akov, "the Heel," and Israel, "God-wrestler." Remembering his names means remembering the whole: the shrewd young trickster, and the patriarch changed by his wrestle with God, and all of his roles and identities in between. When we look at the whole of Jacob's life in this way, I think it's easier to have empathy for how his story ends.

I do think it's okay to blame the curses on dementia while holding on to the blessings. For me, the blessings come from a true place. They come from a heart flowing with love that wants to bestow that love on the generations. The bitter words or curses come from a false place, a mind clouded by confusion. I believe that the loving words are real, and the hurtful words aren't.

And what about us, "the ones who come after?" We're called to compassionate memory. When we remember all of who he was, his "name is recalled in us." Our task is to recall the choices and adventures and accomplishments of our patriarch's lifetime. To hold with compassion the whole of his story: the beginning and middle that came before this runway toward an end.

This is the d'varling I offered at my shul at Kabbalat Shabbat services (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.) Art by Yoram Raanan.

December 15, 2021

Dislocation

I haven't been to Texas since the unveiling of mom's headstone. The backpack I use when traveling has been in the closet a long time. In its pockets I find paper remnants from the Cuba trip in 2019.

I also unearth my pocket Koren siddur which I had given up for lost, and a wooden coin that reads (after Simcha Bunim) on one side "for my sake was the world created" and on the other "I am dust and ashes."

Flying for the first time in almost two years was always going to be strange. Flying for the first time during a global pandemic, even more so. Thankfully no one is belligerent about wearing a mask.

To make the day even more surreal, it turns out my local airport has been redone. New parking garage, new traffic flow, new everything. Delta still flies out of the B gates; at least that hasn't changed.

On the first plane I watch Roadrunner, the Tony Bourdain film. I loved his writing, and the way he brought the world into our living rooms. I loved how much he seemed to love the wide world.

There's a sense of dislocation in the film. The dislocation of travel, especially the kind of travel he did 250 days a year. The dislocation of a world where his light shines now only in memory.

My mother was still alive when he killed himself, because I remember talking with her about it a little bit. She was shocked. He seemed to have it all, she said more than once. She admired his work too.

Of course, Tony's suicide shapes the story. Not only his absence, but how much the people who knew him best miss him. I ached to see their anger and grief at his inability to stay in the world with them.

Then again, his loved ones didn't have to see him live to lose his words and his machete-sharp wit and his prodigious memory. Maybe he thought he was doing them a kindness, making his own exit.

Still, I'll bet his daughter would've chosen to get more time with him, even if that meant that she would one day endure the heartbreak of watching his mind and his memory and his awareness disappear.

Loss of memory is the most profound dislocation I can think of. It's often old memories that linger like cigar smoke. The hardest thing is making space to grieve what's been lost -- what's being lost.

Or maybe the hardest thing is grieving the losses without perseveration, without getting stuck in them. Feeling them, and then letting them go -- like the words and memories that recede into mist.

December 7, 2021

Destination

This time in the black Suburban

leading the hearse

and the parade of blinking cars

I remember the drive

to the cemetery in San Antonio

the day we buried Mom.

I don't think I'd ever been

on those roads before, or

if I had, they were different

from this new vantage.

So many switchbacks and turns

past small houses, yards dotted

with pecan and crepe myrtle trees

though nothing was blooming.

After today's burial

my friend the undertaker

asks about the meditation labyrinth

behind the synagogue.

It's a contemplative practice,

I explain. It's not a maze

where it's easy to get lost.

There's only one path.

Take your time, notice

where your footsteps land.

We don't know how or when,

but we all know the destination.

If this poem speaks to you, you might enjoy Crossing the Sea, published by Phoenicia. It's my collection that moves through the first year of mourning my mom.

I should also mention Walking the Labyrinth by my friend and colleague R. Pamela Wax, a new collection of beautiful poems of grief and transformation.

December 4, 2021

Abundance and dreams, resilience and hope: Miketz and Chanukah

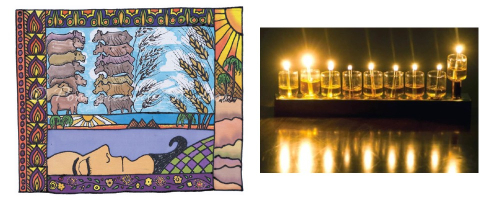

Pharaoh's dreams (artist unknown); an oil-lamp chanukiyah.

Pharaoh's dreams (artist unknown); an oil-lamp chanukiyah.

This week we continue the Joseph story. In this installment, Pharaoh has two disturbing dreams. In one dream, seven happy fat cows emerge from the Nile, followed by seven emaciated cows who eat the fat ones. In the other, the same thing happens with ripe ears of corn and shrunken ones.

No one in his court can interpret the dreams. And then the cupbearer pipes up: I was in your prison a while back, and there was a Hebrew prisoner who interpreted dreams! So Pharaoh sends for Joseph, who says, the dreams mean that seven good years are coming, followed by seven years of famine.

Joseph tells Pharaoh to set someone wise in charge of his storehouses, someone who can save during the years of plenty so there will be food to eat in the lean times. Pharaoh promptly promotes him, saying, "Could we ever possibly find another man like him, a man in whom is the spirit of God?"

(Or in the words of Lin-Manuel Miranda, "Hey yo, I'm gonna need a right-hand man.")

Pharaoh's dreams are about guarding our resources. When there is abundance, set some aside and save it for when there won't be. And this isn't just about individual households saving what they can; Joseph sets aside grain for the whole nation, so the government can make sure everyone makes it through.

Every year, we read this at Chanukah. As my b-mitzvah students learned this week, there are different stories we can tell about Chanukah. One is the story of oppression and war in the books of Maccabees -- which were not canonized into the Hebrew Bible, though they are part of some Christian Bibles.

Another is the story of the sanctified oil that lasted for eight days. That narrative comes to us from Talmud, and it's the one our tradition chose to enshrine. That Chanukah story is a story about hope, and enough-ness, and the leap into faith when we don't feel like we have enough fuel to keep hope burning.

Sometimes we feel like we don't have enough. Maybe we feel that we ourselves aren't enough. Maybe life feels overwhelming, and in the words of the poet William Stafford, "The darkness around us is deep." The Chanukah story asks us to kindle light exactly then. That's when we need hope most.

This week Torah says: don't use everything up -- resources are finite! Save some of what you have so you can help everyone make it through the lean times! Meanwhile the Chanukah story says: kindle the eternal light, even if you're going to run out of oil! So which one is right? They both are.

The Torah teaching is about things we can touch: protecting our natural resources, not eating all the grain, making sure we can feed people when there's famine. The Chanukah teaching is metaphysical: it's not about oil, but about hope. It's about kindling hope in our hearts, and keeping hope burning.

Earth and water and air and trees and food are finite, and we need to steward them carefully and share them equitably -- that's a big one, we're working on that. But hope provides its own fuel. And like love, it doesn't diminish when we share it. Being a Jew -- for me -- means living up to both of these truths.

We need to be wise with our resources, and help people who live at sea level, and nations that don't yet have enough vaccines. That's never been more true than it is now. And we need to keep hope kindled in our hearts, even when the world seems hopeless, especially when the world seems hopeless.

The Hasidic master Reb Nachman (b. 1772) struggled with depression. And yet he taught that despair is a sin. Because despair means the complete absence of hope. And that means we've given up on each other, and on ourselves, and on God. And if we've given up, we won't work to repair what's broken.

That's another thing it means to me to be a Jew: tikkun olam, repairing our broken world. We are God's hands in the world. It's aleinu, it's on us, to build a world of greater justice and love and hope -- and not to give up.

This is the d'varling I offered at my shul on Shabbat Chanukah (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers