Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 321

June 21, 2011

Blackout

We have no internet. TWO DAYS and no internet in sight. I'm at MacDonald's right now, so all the pending comments have been approved, but it's going to be awhile before I get back to reading everything. Play amongst yourselves. Be nice. Floss. I should be back by Thursday or Friday. Maybe.

AAARRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRGH.

June 19, 2011

Useful Quotes

I've been thinking about the quotes we use here at Squalor on the River. Not famous movie quotes like "That's Chinatown, Jake" or "As God is my witness, I'll never go hungry again," but the ones I use over and over again as shorthand. Some are from movies, some are from TV shows, some are from songs, one is from a cartoon, another is from an old light bulb joke, another from an old vaudeville routine, but they're all things that not only shorthand whatever experience we're discussing but generally make us laugh, too. My faves:

"Sorry. Sorry. Just thrilled to be alive."

"Don't you judge me!"

"We can't stop here. This is bat country."

"She's ooooooold, isn't she, Bruce?"

"Cats and dogs, living together."

"It was bad. It was bad. Well, not that bad, but Lord it wasn't good."

"Sonofabitch must pay."

"Push the button, Max."

"Well, this looks like the inside of a goat's stomach."

"I'm not dead yet."

"I really like your shooooes." (Said as a threat.)

"Slowly I turn. Inch by inch, step by step . . ."

"Everybody dies." (Said soothingly.)

"It's all right. I'll just sit here alone. In the dark."

What are yours?

June 14, 2011

Mystery List, Expanded and Revised and Now Updated

Update:

I looked up availability which changed things some since if it's not streaming, it's too hard for everybody to get (no Jonathan Creek, which is a crime). See annotated list below.

Okay, here's the latest version of the mystery list with your suggestions. THIS MUST BE CUT. Or we're going to have another nine-month series. And it got longer because Lani and Alastair pointed out that we didn't have Supernatural Mysteries on there, and I'm a sucker for Supernatural Mysteries. The numbers in parentheses are the maximum number of titles for that subgenre. The ones in the caps are the ones that are staying no matter what. Because I said so. Now eat your peas.

New Mystery List:

September: Classic Mystery Plots (6)

1934 THE THIN MAN (streaming on Amazon: DVD rental on Netflix)

1974 MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1993 THE FUGITIVE (streaming on free on Amazon Prime, rental on Netflix)

1997 JONATHAN CREEK (not available for streaming)

2010 SHERLOCK (streaming on Amazon and Netflix; rental on Netflix)

and two others:

1954 Rear Window (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1994 The Client (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

2006 Déjà Vu (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Witness for the Prosecution (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Presumed Innocent (streaming on Amazon Prime (free) and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

The Prestige (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Gosford Park (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

Inside Man (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

The Negotiator (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Bunny Lake is Missing (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Gone Baby Gone (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1950 DOA (streaming on Amazon)

Deathtrap (streaming on Amazon free)

The Last of Sheila (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Twelve Angry Men (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

The General's Daughter (streaming on Amazon but only to buy for $9.99, rental on Netflix)

Anatomy of a Murder (streaming on Amazon but only to buy for $9.99, rental on Netflix)

No Way Out (streaming on Amazon)

Klute (streaming on Amazon free, rental on Netflix)

October/November: Noir Mystery Plots (8)

1941 THE MALTESE FALCON (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1944 LAURA (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1946 THE BIG SLEEP (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1974 CHINATOWN (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1997 LA CONFIDENTIAL (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

2005 KISS KISS BANG BANG (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

2006 BRICK (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

TV: VERONICA MARS (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

Unless somebody argues passionately to replace one with one of these:

1947 Out of the Past (rental on Netflix)

1958 Vertigo (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1995 Devil in a Blue Dress (rental on Netflix)

1981 Body Heat (streaming Amazon Prime (free) and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

December/January: Romantic Mystery Plots (5)

1963 CHARADE (streaming Amazon Prime (free) and on Netflix, rental on Netflix)

1987 THE BIG EASY (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

And three others:

1976 Silver Streak (streaming on Amazon)

1978 Foul Play (rental on Netflix)

1955 To Catch a Thief (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1991 Dead Again (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

TV: Moonlighting ()

Compromising Positions ()

February: Comic Mystery Plots (5)

1985 CLUE (streaming on Amazon but you have to buy it for $7.49, rental on Netflix)

1988 WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? (rental on Netflix)

2007 HOT FUZZ (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

And three others:

1998 The Big Lebowski (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

1964 A Shot in the Dark (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1985 Fletch (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

Psych (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

Keen Eddie (rental on Netflix)

High Anxiety (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

March: Supernatural Mystery Plots (4)

THE FRIGHTENERS (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

SLEEPY HOLLOW (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

TV: SUPERNATURAL (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

And one other

X-Files (streaming on Amazon and Netflix, rental on Netflix)

Ghost (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

What Lies Beneath (streaming on Amazon but only to buy for $9.99)

April: Non-Traditional Mystery Plots (5)

1945 And Then There Were None (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1950 Rashomen (streaming on Netflix, rental on Netflix)

1995 The Usual Suspects (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1996 Fargo (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

1996 Lone Star (rental on Netflix)

1998 Wild Things (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

2000 Memento (streaming on Amazon, rental on Netflix)

TV: Columbo (streaming on Netflix, rental on Netflix)

Lantana (rental on Netflix)

Please keep in mind that the movie has to be something that has a strong enough structure that we can learn to plot mysteries from it. The fact that it's a good movie is not enough. We have a goal here, let's keep our eyes on the prize.

Now fight it out amongst yourselves. The decisions of the judges (me, Lani, Alastair) are final. No salemen will call. DON'T NOMINATE ANY MORE MOVIES. Because the list is too long already. Unless they're Supernatural Mysteries because we just sprang that one on you. Thank you.

Mystery List, Expanded and Revised

Okay, here's the latest version of the mystery list with your suggestions. THIS MUST BE CUT. Or we're going to have another nine-month series. And it got longer because Lani and Alastair pointed out that we didn't have Supernatural Mysteries on there, and I'm a sucker for Supernatural Mysteries. The numbers in parentheses are the maximum number of titles for that subgenre. The ones in the caps are the ones that are staying no matter what. Because I said so. Now eat your peas.

New Mystery List:

September: Classic Mysteries (6)

1934 THE THIN MAN

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1997 JONATHAN CREEK (TV)

2010 SHERLOCK (TV)

1954 Rear Window

1993 The Fugitive

1994 The Client

Witness for the Prosecution

Presumed Innocent

The Prestige

Gosford Park

Inside Man

The Negotiator

Bunny Lake is Missing

Gone Baby Gone

DOA

Deathtrap

The Last of Sheila

Twelve Angry Men

The General's Daughter

Anatomy of a Murder

No Way Out

Klute

October/November: Noir Mysteries (7)

1941 THE MALTESE FALCON

1944 LAURA

1974 Chinatown

1989 Sea of Love

1997 LA CONFIDENTIAL

2005 KISS KISS BANG BANG

2006 BRICK

TV: VERONICA MARS

Devil in a Blue Dress

The Big Sleep (Bogie or Mitchum?)

Out of the Past

Body Heat

Vertigo

December/January: Romantic Mysteries (7)

1955 To Catch a Thief

1963 CHARADE

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1987 THE BIG EASY

1991 Dead Again

TV: Moonlighting

Compromising Positions

Deja Vu

February: Comedy Mysteries (4)

1964 A Shot in the Dark*

1985 Fletch

1985 CLUE

1988 Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

1998 The Big Lebowski

2007 HOT FUZZ

TV: Psych or Keen Eddie

High Anxiety

March: Supernatural Mysteries (4)

The Frighteners

Sleepy Hollow

TV: Supernatural

TV: X-Files

April: Non-Traditional Mysteries (5)

And Then There Were None (haven't picked a version)

1950 Rashomen

1995 The Usual Suspects

1996 Fargo

1996 Lone Star

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

TV: Columbo

Lantana

Please keep in mind that the movie has to be something that has a strong enough structure that we can learn to plot mysteries from it. The fact that it's a good movie is not enough. We have a goal here, let's keep our eyes on the prize.

Now fight it out amongst yourselves. The decisions of the judges (me, Lani, Alastair) are final. No salemen will call. DON'T NOMINATE ANY MORE MOVIES. Because the list is too long already. Unless they're Supernatural Mysteries because we just sprang that one on you. Thank you.

June 13, 2011

Mysteries: First Draft of PopD Series

So we have a definition:

"A mystery is a story in which a protagonist solves a puzzle/mystery/crime."

And we have a plan: We're going to start with the baseline of the classic mystery plot and then look at how the subgenres work within that plot.

And we have a draft list for discussion; suggestions for other title welcomed (the numbers after the subtitle show how many movies we need for that subsection):

September: Classic Mysteries (6)

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1996 Lone Star

1997 Jonathan Creek

2010 Sherlock

1954 Rear Window

1993 The Fugitive

1994 The Client

October/November: Noir Mysteries (7)

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1974 Chinatown

1987 The Big Easy

1989 Sea of Love

1997 LA Confidential

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

Veronica Mars

December/January: Romantic Mysteries (7)

1934 The Thin Man

1944 Laura

1955 To Catch a Thief

1963 Charade

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1991 Dead Again

Moonlighting

February: Comedy Mysteries (4)

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1955 The Trouble with Harry

1964 A Shot in the Dark*

1976 Family Plot

1976 Murder by Death*

1985 Fletch

1985 Clue*

1988 The Naked Gun*

1988 Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

1998 The Big Lebowski

2007 Hot Fuzz

*anything with an asterisk is farce

Psych or Keen Eddie

March: Non-Traditional Mysteries (4)

1950 Rashomen

1995 The Usual Suspects

1996 Fargo

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

Columbo

What should stay, what should go, what did we miss?

June 12, 2011

Mysteries, Anybody?

I've been underwater here for awhile (mentally, not the river), letting down everybody I know, and I'm trying to claw my way out, so tonight I sat with Lani and Alastair and talked story and TV and politics and PopD for hours. I need to talk to other people more. I get all caught up in my own mind and there are some dark, dark places in there. Anyway, we were talking about how PopD has, sort of, lost its way. When we started, it was a project for Lani and me to learn about and clarify our ideas about writing romantic comedy. We did that for nine months, after which we really needed a break from The Big Misunderstanding and The Romcom Run, so we started doing short series that were interesting but not really helpful. So talking tonight, we realized that we both really want to understand writing mystery plots better. Or at all, for that matter. Back in the 80s, I did my master's thesis on mystery fiction, so I've been a fan for a long, long time, but writing those suckers is completely different. And so we are thinking about putting PopD on hiatus after the TV pilot series and coming back in September with a shorter (four months maybe?) survey of mystery films, doing the same thing we did with romcom: trying to discover what works and what doesn't, but concentrating on plot this time. So I drew up a list of movies based on my faves, internet faves, and Alastair and Lani's picks (Brick and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang) that we would eventually cut to twenty-four or twenty-five. It has some losers and some flaws (somebody else besides Hitchcock must have made mysteries in the fifties) but it's a starting place. Check over the list below and see if we missed anything crucial. Remember, we're talking about mysteries and plotting, so straight suspense really isn't applicable. We want Whodunnits (although the thing they dun doesn't have to be murder).

Here's the first draft of the list. It's divided into decades for no particular reason except that we would like to have a span of time periods. Have at it:

1934 The Thin Man

1935 The 39 Steps (Hitchcock)

1938 The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock)

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1944 Laura

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1949 The Third Man

1950 Rashomen

1951 Strangers on a Train (Hitchcock)

1954 Rear Window (Hitchcock)

1954 Dial M for Murder (Hitchcock)

1955 To Catch a Thief (Hitchcock)

1955 The Trouble with Harry (Hitchcock)

1959 North by Northwest (Hitchcock)

1960 Psycho (Hitchcock)

1963 Charade

1967 In the Heat of the Night

1971 Klute

1972 Sleuth

1974 Chinatown

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1978 The Big Sleep

1981 Blowout

1983 Eddie and the Cruisers

1987 The Big Easy

1988 Alien Nation

1988 The Presidio

1989 Sea of Love

1991 Dead Again

1994 The Client

1995 The Usual Suspects

1997 LA Confidential

1997 Jonathan Creek

1998 The Big Lewbowski

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

2003 Mystic River

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

2007 Hot Fuzz

2010 Sherlock

Edited to Add:

Or would it be smarter to do mysteries as subgenres instead of chronologically:

Classic Mysteries (as in classic mystery plots)

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1981 Blowout

1997 Jonathan Creek

2010 Sherlock

Hitchcock Mysteries

1935 The 39 Steps (Hitchcock)

1938 The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock)

1951 Strangers on a Train (Hitchcock)

1954 Rear Window (Hitchcock)

1954 Dial M for Murder (Hitchcock)

1955 To Catch a Thief (Hitchcock)

1955 The Trouble with Harry (Hitchcock)

1959 North by Northwest (Hitchcock)

1960 Psycho (Hitchcock)

Romantic Mysteries

1934 The Thin Man

1944 Laura

1963 Charade

1991 Dead Again

Noir Mysteries

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1949 The Third Man

1978 The Big Sleep

1974 Chinatown

1997 LA Confidential

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

Comedy Mysteries

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1998 The Big Lewbowski

2007 Hot Fuzz

And wherever these would go:

1950 Rashomen

1967 In the Heat of the Night

1971 Klute

1972 Sleuth

1983 Eddie and the Cruisers

1987 The Big Easy

1988 Alien Nation

1988 The Presidio

1989 Sea of Love

1994 The Client

1995 The Usual Suspects

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

2003 Mystic River

June 7, 2011

Discovering A New Gal-axy: The Bettyverse

Lani Diane Rich's A Year and Change is done: She's forty, fully recovered from divorced-crazy, ecstatically remarried to a terrific guy who is also a terrific stepfather, and ready to move on from blogging daily. So Lani (aka Lucy March) and aforesaid wonderful husband have opened a new website, dedicated to the idea that all people have something to say and something to share–great stories, sympathy, solutions, bacon recipes, whatever. So go check out the brand new, shiny Bettyverse. Really nice people live there and they'd love to talk to you.

June 5, 2011

Alison Does Great Collage

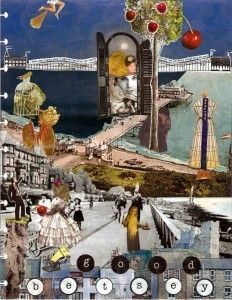

About a million years ago (okay, probably about four or five years ago), I taught at a beach retreat and met Alison, a terrific writer who wanted to be a better writer. Toward the end of the retreat, I did a collage workshop and Alison caught fire and did something amazing. Then after the retreat, she did something even more amazing: she turned collaging into notetaking, plotting, and real art, which she showed me when I met her again at a local RWA meeting. I said, "Send me those so I can put some of this up on Argh," and she did. Except she sent it to me at the exact moment I was changing from an old laptop to a new laptop and I missed a couple of e-mails when I changed over. Fast forward three years later and I'm finally cleaning off the old laptop because my now three-year-old newer one is having battery troubles, and there's Alison's e-mail with a jpg of her note cards and one of her collage pages. Look at this (click on the images to make them larger):

Don't you want to read that book? I can't stop staring at the collage. But she also does a kind of note collage thing that's really smart. Here are some of her cards:

So here's what Alison said about her process:

"On the scene cards:

*The act the scene's in (with the title of the act, and the

protag-action sentence)

*A picture of something significant in the scene (pulled most of these

from my research files on Curio)

*The number, title, and synopsis of the scene

*The scene's POV (also indicated by the color of the text box), the

protag and antag (happy to report I now have one of each in

almost–almost!–every scene), and the number of pages.

*The cards themselves are color-coded–a different color for each act

(Again, my heartfelt thanks for giving me a systematic way to think

about these things. Like you say, it's not what I need to think about

when I'm finding the characters and story, but it sure does help with

revision. Doesn't make revision easier–it's harder in many ways–but

it makes it…hmm…worthwhile, I guess. Like having the right

brushes can make all the difference in a painting. Thank you.)

*On the back of the cards, I jot notes–things to add, change, look

up, research…"

Basically, Alison is freaking brilliant. And I want to frame her collage. And use her notecard method, I think. Alison, I owe you.

June 2, 2011

Linear Vs. Patterned: A Brief Discussion of Structure

I just listened to Lani/Lucy and Alastair's podcast on Out of Sight, one of my all time favorite movies and now one of theirs. But we differ radically on how we read the movie, which I pointed out in the comments and then realized that saying, "This is not a fragmented structure, this is a patterned structure" was probably not helpful unless I defined my terms in discussing structure. So this is the Crusie Theory of Structure, not necessarily anybody else's theory of structure.

The important thing about structure in storytelling is that you have one. It doesn't really matter what plan you choose, just have a damn plan. Any plan. Joyce Carol Oates once wrote a short story of twenty-six sentences in which the first sentence began with "A," the second sentence began with "B" . . . I know this because Ron Carlson talked to her about it and then assigned it to me as a writing exercise, at which point I discovered that structure can be an amazing, fluid thing. There are limitless possibilities for structuring a story, which is where the trouble starts.

The problem in choosing a structure is that you have understand the story you're telling because structure has meaning. If you use the wrong structure to tell your story, you distort its meaning. Case in point: Out of Sight. For those of you who have seen this film (and if you haven't, go see it right now), imagine rearranging the scenes in chronological order. See? It's a different movie with a different, weaker, much less interesting focus. On the other hand, Pulp Fiction was followed by several movies told in fragmented structure that were knee-capped by not being told chronologically. Generally speaking, chronological, linear plotting is the writer's friend because viewers and readers are used to it. But if your story wants to be something other than the unfolding of events, you need to listen to it. For the purposes of this discussion, I'm going to stick to linear and patterned structures, but really, you can do anything you damn well want as long as your story consents.

Linear structure is as old as Aristotle (and he's old, isn't he, Bruce?). [Sorry, couldn't resist. It's one of our go-to movie quotes, from His Girl Friday.] I'd say older, but a lot of the really old stories are more picaro than focused linear, and I don't want to get into that. Why is linear structure so old and so ingrained? Because it reflects the male life experience. It begins with the birth of an idea/event/problem/struggle, rises through the ranks accumulating power and tension, and then achieves the climax of its path/career, after which it retires. You may also notice that that's the trajectory of the male sexual experience. People tell stories that reflect their experiences and for a long time, patriarchal power was so entrenched that acknowledged storytellers were predominantly male.

But of course back in the kitchen, women were telling stories, too. The difference was, they were telling patterned stories, stories that emphasized detail and repetition, that built up meaning through the relationships of events, recurring climaxes that achieved meaning through their juxtaposition with each other. That structure replicated their traditional lives of doing the same thing each day, over and over, so that detail and subtle change took on huge meaning because of the repetition. Each day was its own story, part of a bigger story formed by the pattern of those days. And if you really look at that, it's the female sexual experience. (You guys think we can't focus? That's why we have multiple climaxes, suckers.)

The next part of this is sexist because it implies that men tell stories one way and women another and that's clearly wrong. Scott Frank (writer) and Steven Soderburg (director) did a masterful job of telling a patterned story, and women writers have been telling razor-sharp linear stories for centuries. But for the purpose of this argument, let's stick with the male-vs.-female bit for a while.

So imagine a man coming home to his wife and saying, "I saw John today. He's getting married." After which his wife asks who John's getting married to, how they met, how he looked when he talked about her, when the wedding is, how her mother feels about it, how his mother feels about it, how John's ex-wife feels about it . . . The husband can probably tell her who John's getting married to, but after that he just thinks she's crazy: he gave her the important info, what's her problem? She thinks he's hopeless: he's left out all the stuff that matters.

Or if you will, a man tries to tell a woman a joke.

Man: "This traveling salesman meets this farmer's daughter . . . "

Woman: "How old is she?"

Man: "What difference does it make?"

Woman: "Is she sixteen and innocent or forty and jaded?"

Man: "I don't know. She's . . . twenty."

Woman: "What's he selling?"

Man: "How the hell should I know what he's selling?"

Woman: "Is he selling pots and pans or condoms?"

Man: "Can I just tell this story?"

Woman: "Evidently not. You don't know the important stuff."

Meanwhile, when a woman tries to tell a joke, she has a hell of a time because most jokes only work if they're told in a strict linear fashion. You tell a joke out of order, there's no joke. I make speeches all the time, I tell jokes all the time, and it's HELL because I desperately want to embroider the story with details and character; the joke just wants to get to the punch line.

And that's what a linear plot wants to do, it wants to get to the punch line, the big obligatory scene, the climax, after which it rolls over and has a cigarette in the denouement. A leads to B, which leads to C, which leads to D . . . It's chronological, it is above all logical, and the build to the great climax leaves the listener/reader/viewer satisfied. It's also the way 95% of modern stories are told, so it's your safest bet.

However, sometimes your story isn't about what happens next. Sometimes it's about the pattern of events, the accumulation of small crises, the juxtaposition of character reactions, the layering of behaviors that make a character deeper and more faceted and the release of the information about that layering in juxtaposition with other characters (how her mother feels about it, how his mother feels about it, how his ex-wife feels about it). It's not the cause and effect that matters, it's the pattern.

A brilliant example of this is Margaret Atwood's "Rape Fantasies," which begins as a woman talks about listening to her co-workers talking about rape fantasies at lunch and then begins to tell about her rape fantasies, although not to her friends, that lunch is over. She tells the short (and very funny) stories without escalating in any way, they're just fantasies that have no cause-and-effect relationship to each other, they don't lead to each other, they just exist, stories she pulls off the shelf of her imagination and retells to comfort herself. It's only when you see the pattern among the stories that you begin to understand who this woman is, what she desperately wants (fantasizes about). And then Atwood delivers a knock-out of an ending that makes you look at all of the stories as a whole. That story cannot be told in chronological order; it requires patterned structure.

So in a patterned novel or film (damn hard to pull off), you need to construct pieces that are complete in and of themselves, scene sequences that form complete stories, and then juxtapose them with other pieces to make a pattern so that at the end, the pattern is the meaning of the story. Think of the scene sequences as quilt blocks, beautiful on their own, and the story as the finished quilt in which the blocks disappear when it's finished to form a patterned whole. The blocks are beautiful, but it's the quilt as a whole that's the finished design.

So if you put Out of Sight in chronological order, it's the story of a charming but hapless bank robber, a trickster who gets caught three times because of the people he cares for. And, I think, you'd get a little impatient with Jack for not being smarter about people; if you're going to be a top-notch bank robber, you need to be ruthless. C'mon, Jack, get it together.

But that's not Jack's story. Jack is a trickster with a problem: he likes people so he's loyal to them. Big flaw in a trickster who has to stand above the action while manipulating reality. Jack's a genius at shifting reality, but then he connects to people and it all goes to hell. So Jack's story is a pattern of events where he shifts reality brilliantly and then has reality shifted back on him by people he cares about; his struggle is that the two halves of his nature–trickster and caretaker–are at war with each other. Even so, he's doing pretty good until he meet Karen. Karen's problem is that she's a born trickster, her instincts are to move outside the law, but her daddy is a lawman, and she wants to please her daddy (who, to be fair, adores her and is a great father) so now she's a marshall out to get Jack. And her story is now a pattern of events where her two sides–trickster and lawkeeper–are at war with each other. Either story is interesting by itself, but when the two stories are placed in juxtaposition with each other, they're both intensified, not just because Jack and Karen fall in love, but because they fall in love with the thing in each other they're fighting every day. Their love story becomes part of the pattern of their main story, Jack's attempts to escape and Karen's attempts to bring him in. That description sounds boring, but as patterned plot of two tricksters in an intricate dance, it's fantastic. Then add the quilt blocks of the supporting cast–Snoop the genial psychotic, Buddy the honest crook, Ripley the cowardly man of power, Glenn the innocent murderer–and you have a pattern of stress and paradox, each piece increasing the tension in the next. You can't tell that story in chronological order because what happens next isn't important. It's what happens when you put this scene sequence next to that sequence, the pattern that forms when the quilt blocks of scenes are sewn together.

Needless to say, patterned structures are a bitch to make work, particularly in long form. The story has to really need that structure to pull it off. But when it works, it's amazing. How amazing? Watch this patterned, detailed love scene sequence between two tricksters. Then imagine it done in two separate chronological sequences. The patterned version is about character, about relationship, about fantasy and connection and desire; the linear version would be about a pick-up in a bar followed by sex. Nothing wrong with that second one, it's just not the way this story needs to be told.

Structure isn't just a way to tell a story, it gives meaning to the story, it informs and intensifies the story, it says "This is what is important here, this is what you need to pay attention to." Most of the time, most stories need linear structure, but when a story says, "I don't care what happens next, I care what these things together mean," you're looking at a patterned structure.

May 29, 2011

Wonder Woman of Publishing

So one of the five thousand things I'm behind on (besides the Trickster discussion, new post coming as soon as I get it out of draft form) is my presentation for National on publishing. I've been trying to figure out how to do it without being boring and then inspiration struck:

See? Not boring. (Click on the slide to see it bigger. Or not. Up to you.)

I have thirty one-word slides, the presentation is almost done, and I have to say, I think I'm brilliant. For example, there's this one:

Or this one:

Or this one:

Okay, that one I'll probably cut. But my favorite is this one:

Of course, it's 5AM, and I often think I'm a genius at 5AM, and then the cold, cruel light of dawn comes and I realize I was just giddy from lack of sleep. But still, great idea for a publishing talk, don't you think? Huh? HUH?

Okay, what do you think I should talk about?