Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 324

June 13, 2011

Mysteries: First Draft of PopD Series

So we have a definition:

"A mystery is a story in which a protagonist solves a puzzle/mystery/crime."

And we have a plan: We're going to start with the baseline of the classic mystery plot and then look at how the subgenres work within that plot.

And we have a draft list for discussion; suggestions for other title welcomed (the numbers after the subtitle show how many movies we need for that subsection):

September: Classic Mysteries (6)

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1996 Lone Star

1997 Jonathan Creek

2010 Sherlock

1954 Rear Window

1993 The Fugitive

1994 The Client

October/November: Noir Mysteries (7)

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1974 Chinatown

1987 The Big Easy

1989 Sea of Love

1997 LA Confidential

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

Veronica Mars

December/January: Romantic Mysteries (7)

1934 The Thin Man

1944 Laura

1955 To Catch a Thief

1963 Charade

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1991 Dead Again

Moonlighting

February: Comedy Mysteries (4)

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1955 The Trouble with Harry

1964 A Shot in the Dark*

1976 Family Plot

1976 Murder by Death*

1985 Fletch

1985 Clue*

1988 The Naked Gun*

1988 Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

1998 The Big Lebowski

2007 Hot Fuzz

*anything with an asterisk is farce

Psych or Keen Eddie

March: Non-Traditional Mysteries (4)

1950 Rashomen

1995 The Usual Suspects

1996 Fargo

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

Columbo

What should stay, what should go, what did we miss?

June 12, 2011

Mysteries, Anybody?

I've been underwater here for awhile (mentally, not the river), letting down everybody I know, and I'm trying to claw my way out, so tonight I sat with Lani and Alastair and talked story and TV and politics and PopD for hours. I need to talk to other people more. I get all caught up in my own mind and there are some dark, dark places in there. Anyway, we were talking about how PopD has, sort of, lost its way. When we started, it was a project for Lani and me to learn about and clarify our ideas about writing romantic comedy. We did that for nine months, after which we really needed a break from The Big Misunderstanding and The Romcom Run, so we started doing short series that were interesting but not really helpful. So talking tonight, we realized that we both really want to understand writing mystery plots better. Or at all, for that matter. Back in the 80s, I did my master's thesis on mystery fiction, so I've been a fan for a long, long time, but writing those suckers is completely different. And so we are thinking about putting PopD on hiatus after the TV pilot series and coming back in September with a shorter (four months maybe?) survey of mystery films, doing the same thing we did with romcom: trying to discover what works and what doesn't, but concentrating on plot this time. So I drew up a list of movies based on my faves, internet faves, and Alastair and Lani's picks (Brick and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang) that we would eventually cut to twenty-four or twenty-five. It has some losers and some flaws (somebody else besides Hitchcock must have made mysteries in the fifties) but it's a starting place. Check over the list below and see if we missed anything crucial. Remember, we're talking about mysteries and plotting, so straight suspense really isn't applicable. We want Whodunnits (although the thing they dun doesn't have to be murder).

Here's the first draft of the list. It's divided into decades for no particular reason except that we would like to have a span of time periods. Have at it:

1934 The Thin Man

1935 The 39 Steps (Hitchcock)

1938 The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock)

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1944 Laura

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1949 The Third Man

1950 Rashomen

1951 Strangers on a Train (Hitchcock)

1954 Rear Window (Hitchcock)

1954 Dial M for Murder (Hitchcock)

1955 To Catch a Thief (Hitchcock)

1955 The Trouble with Harry (Hitchcock)

1959 North by Northwest (Hitchcock)

1960 Psycho (Hitchcock)

1963 Charade

1967 In the Heat of the Night

1971 Klute

1972 Sleuth

1974 Chinatown

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1978 The Big Sleep

1981 Blowout

1983 Eddie and the Cruisers

1987 The Big Easy

1988 Alien Nation

1988 The Presidio

1989 Sea of Love

1991 Dead Again

1994 The Client

1995 The Usual Suspects

1997 LA Confidential

1997 Jonathan Creek

1998 The Big Lewbowski

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

2003 Mystic River

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

2007 Hot Fuzz

2010 Sherlock

Edited to Add:

Or would it be smarter to do mysteries as subgenres instead of chronologically:

Classic Mysteries (as in classic mystery plots)

1974 Murder on the Orient Express

1981 Blowout

1997 Jonathan Creek

2010 Sherlock

Hitchcock Mysteries

1935 The 39 Steps (Hitchcock)

1938 The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock)

1951 Strangers on a Train (Hitchcock)

1954 Rear Window (Hitchcock)

1954 Dial M for Murder (Hitchcock)

1955 To Catch a Thief (Hitchcock)

1955 The Trouble with Harry (Hitchcock)

1959 North by Northwest (Hitchcock)

1960 Psycho (Hitchcock)

Romantic Mysteries

1934 The Thin Man

1944 Laura

1963 Charade

1991 Dead Again

Noir Mysteries

1941 The Maltese Falcon

1949 The Third Man

1978 The Big Sleep

1974 Chinatown

1997 LA Confidential

2005 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

2006 Brick

Comedy Mysteries

1944 Arsenic and Old Lace

1976 Silver Streak

1978 Foul Play

1998 The Big Lewbowski

2007 Hot Fuzz

And wherever these would go:

1950 Rashomen

1967 In the Heat of the Night

1971 Klute

1972 Sleuth

1983 Eddie and the Cruisers

1987 The Big Easy

1988 Alien Nation

1988 The Presidio

1989 Sea of Love

1994 The Client

1995 The Usual Suspects

1998 Wild Things

2000 Memento

2003 Mystic River

June 7, 2011

Discovering A New Gal-axy: The Bettyverse

Lani Diane Rich's A Year and Change is done: She's forty, fully recovered from divorced-crazy, ecstatically remarried to a terrific guy who is also a terrific stepfather, and ready to move on from blogging daily. So Lani (aka Lucy March) and aforesaid wonderful husband have opened a new website, dedicated to the idea that all people have something to say and something to share–great stories, sympathy, solutions, bacon recipes, whatever. So go check out the brand new, shiny Bettyverse. Really nice people live there and they'd love to talk to you.

June 5, 2011

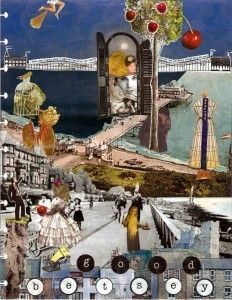

Alison Does Great Collage

About a million years ago (okay, probably about four or five years ago), I taught at a beach retreat and met Alison, a terrific writer who wanted to be a better writer. Toward the end of the retreat, I did a collage workshop and Alison caught fire and did something amazing. Then after the retreat, she did something even more amazing: she turned collaging into notetaking, plotting, and real art, which she showed me when I met her again at a local RWA meeting. I said, "Send me those so I can put some of this up on Argh," and she did. Except she sent it to me at the exact moment I was changing from an old laptop to a new laptop and I missed a couple of e-mails when I changed over. Fast forward three years later and I'm finally cleaning off the old laptop because my now three-year-old newer one is having battery troubles, and there's Alison's e-mail with a jpg of her note cards and one of her collage pages. Look at this (click on the images to make them larger):

Don't you want to read that book? I can't stop staring at the collage. But she also does a kind of note collage thing that's really smart. Here are some of her cards:

So here's what Alison said about her process:

"On the scene cards:

*The act the scene's in (with the title of the act, and the

protag-action sentence)

*A picture of something significant in the scene (pulled most of these

from my research files on Curio)

*The number, title, and synopsis of the scene

*The scene's POV (also indicated by the color of the text box), the

protag and antag (happy to report I now have one of each in

almost–almost!–every scene), and the number of pages.

*The cards themselves are color-coded–a different color for each act

(Again, my heartfelt thanks for giving me a systematic way to think

about these things. Like you say, it's not what I need to think about

when I'm finding the characters and story, but it sure does help with

revision. Doesn't make revision easier–it's harder in many ways–but

it makes it…hmm…worthwhile, I guess. Like having the right

brushes can make all the difference in a painting. Thank you.)

*On the back of the cards, I jot notes–things to add, change, look

up, research…"

Basically, Alison is freaking brilliant. And I want to frame her collage. And use her notecard method, I think. Alison, I owe you.

June 2, 2011

Linear Vs. Patterned: A Brief Discussion of Structure

I just listened to Lani/Lucy and Alastair's podcast on Out of Sight, one of my all time favorite movies and now one of theirs. But we differ radically on how we read the movie, which I pointed out in the comments and then realized that saying, "This is not a fragmented structure, this is a patterned structure" was probably not helpful unless I defined my terms in discussing structure. So this is the Crusie Theory of Structure, not necessarily anybody else's theory of structure.

The important thing about structure in storytelling is that you have one. It doesn't really matter what plan you choose, just have a damn plan. Any plan. Joyce Carol Oates once wrote a short story of twenty-six sentences in which the first sentence began with "A," the second sentence began with "B" . . . I know this because Ron Carlson talked to her about it and then assigned it to me as a writing exercise, at which point I discovered that structure can be an amazing, fluid thing. There are limitless possibilities for structuring a story, which is where the trouble starts.

The problem in choosing a structure is that you have understand the story you're telling because structure has meaning. If you use the wrong structure to tell your story, you distort its meaning. Case in point: Out of Sight. For those of you who have seen this film (and if you haven't, go see it right now), imagine rearranging the scenes in chronological order. See? It's a different movie with a different, weaker, much less interesting focus. On the other hand, Pulp Fiction was followed by several movies told in fragmented structure that were knee-capped by not being told chronologically. Generally speaking, chronological, linear plotting is the writer's friend because viewers and readers are used to it. But if your story wants to be something other than the unfolding of events, you need to listen to it. For the purposes of this discussion, I'm going to stick to linear and patterned structures, but really, you can do anything you damn well want as long as your story consents.

Linear structure is as old as Aristotle (and he's old, isn't he, Bruce?). [Sorry, couldn't resist. It's one of our go-to movie quotes, from His Girl Friday.] I'd say older, but a lot of the really old stories are more picaro than focused linear, and I don't want to get into that. Why is linear structure so old and so ingrained? Because it reflects the male life experience. It begins with the birth of an idea/event/problem/struggle, rises through the ranks accumulating power and tension, and then achieves the climax of its path/career, after which it retires. You may also notice that that's the trajectory of the male sexual experience. People tell stories that reflect their experiences and for a long time, patriarchal power was so entrenched that acknowledged storytellers were predominantly male.

But of course back in the kitchen, women were telling stories, too. The difference was, they were telling patterned stories, stories that emphasized detail and repetition, that built up meaning through the relationships of events, recurring climaxes that achieved meaning through their juxtaposition with each other. That structure replicated their traditional lives of doing the same thing each day, over and over, so that detail and subtle change took on huge meaning because of the repetition. Each day was its own story, part of a bigger story formed by the pattern of those days. And if you really look at that, it's the female sexual experience. (You guys think we can't focus? That's why we have multiple climaxes, suckers.)

The next part of this is sexist because it implies that men tell stories one way and women another and that's clearly wrong. Scott Frank (writer) and Steven Soderburg (director) did a masterful job of telling a patterned story, and women writers have been telling razor-sharp linear stories for centuries. But for the purpose of this argument, let's stick with the male-vs.-female bit for a while.

So imagine a man coming home to his wife and saying, "I saw John today. He's getting married." After which his wife asks who John's getting married to, how they met, how he looked when he talked about her, when the wedding is, how her mother feels about it, how his mother feels about it, how John's ex-wife feels about it . . . The husband can probably tell her who John's getting married to, but after that he just thinks she's crazy: he gave her the important info, what's her problem? She thinks he's hopeless: he's left out all the stuff that matters.

Or if you will, a man tries to tell a woman a joke.

Man: "This traveling salesman meets this farmer's daughter . . . "

Woman: "How old is she?"

Man: "What difference does it make?"

Woman: "Is she sixteen and innocent or forty and jaded?"

Man: "I don't know. She's . . . twenty."

Woman: "What's he selling?"

Man: "How the hell should I know what he's selling?"

Woman: "Is he selling pots and pans or condoms?"

Man: "Can I just tell this story?"

Woman: "Evidently not. You don't know the important stuff."

Meanwhile, when a woman tries to tell a joke, she has a hell of a time because most jokes only work if they're told in a strict linear fashion. You tell a joke out of order, there's no joke. I make speeches all the time, I tell jokes all the time, and it's HELL because I desperately want to embroider the story with details and character; the joke just wants to get to the punch line.

And that's what a linear plot wants to do, it wants to get to the punch line, the big obligatory scene, the climax, after which it rolls over and has a cigarette in the denouement. A leads to B, which leads to C, which leads to D . . . It's chronological, it is above all logical, and the build to the great climax leaves the listener/reader/viewer satisfied. It's also the way 95% of modern stories are told, so it's your safest bet.

However, sometimes your story isn't about what happens next. Sometimes it's about the pattern of events, the accumulation of small crises, the juxtaposition of character reactions, the layering of behaviors that make a character deeper and more faceted and the release of the information about that layering in juxtaposition with other characters (how her mother feels about it, how his mother feels about it, how his ex-wife feels about it). It's not the cause and effect that matters, it's the pattern.

A brilliant example of this is Margaret Atwood's "Rape Fantasies," which begins as a woman talks about listening to her co-workers talking about rape fantasies at lunch and then begins to tell about her rape fantasies, although not to her friends, that lunch is over. She tells the short (and very funny) stories without escalating in any way, they're just fantasies that have no cause-and-effect relationship to each other, they don't lead to each other, they just exist, stories she pulls off the shelf of her imagination and retells to comfort herself. It's only when you see the pattern among the stories that you begin to understand who this woman is, what she desperately wants (fantasizes about). And then Atwood delivers a knock-out of an ending that makes you look at all of the stories as a whole. That story cannot be told in chronological order; it requires patterned structure.

So in a patterned novel or film (damn hard to pull off), you need to construct pieces that are complete in and of themselves, scene sequences that form complete stories, and then juxtapose them with other pieces to make a pattern so that at the end, the pattern is the meaning of the story. Think of the scene sequences as quilt blocks, beautiful on their own, and the story as the finished quilt in which the blocks disappear when it's finished to form a patterned whole. The blocks are beautiful, but it's the quilt as a whole that's the finished design.

So if you put Out of Sight in chronological order, it's the story of a charming but hapless bank robber, a trickster who gets caught three times because of the people he cares for. And, I think, you'd get a little impatient with Jack for not being smarter about people; if you're going to be a top-notch bank robber, you need to be ruthless. C'mon, Jack, get it together.

But that's not Jack's story. Jack is a trickster with a problem: he likes people so he's loyal to them. Big flaw in a trickster who has to stand above the action while manipulating reality. Jack's a genius at shifting reality, but then he connects to people and it all goes to hell. So Jack's story is a pattern of events where he shifts reality brilliantly and then has reality shifted back on him by people he cares about; his struggle is that the two halves of his nature–trickster and caretaker–are at war with each other. Even so, he's doing pretty good until he meet Karen. Karen's problem is that she's a born trickster, her instincts are to move outside the law, but her daddy is a lawman, and she wants to please her daddy (who, to be fair, adores her and is a great father) so now she's a marshall out to get Jack. And her story is now a pattern of events where her two sides–trickster and lawkeeper–are at war with each other. Either story is interesting by itself, but when the two stories are placed in juxtaposition with each other, they're both intensified, not just because Jack and Karen fall in love, but because they fall in love with the thing in each other they're fighting every day. Their love story becomes part of the pattern of their main story, Jack's attempts to escape and Karen's attempts to bring him in. That description sounds boring, but as patterned plot of two tricksters in an intricate dance, it's fantastic. Then add the quilt blocks of the supporting cast–Snoop the genial psychotic, Buddy the honest crook, Ripley the cowardly man of power, Glenn the innocent murderer–and you have a pattern of stress and paradox, each piece increasing the tension in the next. You can't tell that story in chronological order because what happens next isn't important. It's what happens when you put this scene sequence next to that sequence, the pattern that forms when the quilt blocks of scenes are sewn together.

Needless to say, patterned structures are a bitch to make work, particularly in long form. The story has to really need that structure to pull it off. But when it works, it's amazing. How amazing? Watch this patterned, detailed love scene sequence between two tricksters. Then imagine it done in two separate chronological sequences. The patterned version is about character, about relationship, about fantasy and connection and desire; the linear version would be about a pick-up in a bar followed by sex. Nothing wrong with that second one, it's just not the way this story needs to be told.

Structure isn't just a way to tell a story, it gives meaning to the story, it informs and intensifies the story, it says "This is what is important here, this is what you need to pay attention to." Most of the time, most stories need linear structure, but when a story says, "I don't care what happens next, I care what these things together mean," you're looking at a patterned structure.

May 29, 2011

Wonder Woman of Publishing

So one of the five thousand things I'm behind on (besides the Trickster discussion, new post coming as soon as I get it out of draft form) is my presentation for National on publishing. I've been trying to figure out how to do it without being boring and then inspiration struck:

See? Not boring. (Click on the slide to see it bigger. Or not. Up to you.)

I have thirty one-word slides, the presentation is almost done, and I have to say, I think I'm brilliant. For example, there's this one:

Or this one:

Or this one:

Okay, that one I'll probably cut. But my favorite is this one:

Of course, it's 5AM, and I often think I'm a genius at 5AM, and then the cold, cruel light of dawn comes and I realize I was just giddy from lack of sleep. But still, great idea for a publishing talk, don't you think? Huh? HUH?

Okay, what do you think I should talk about?

May 24, 2011

May 20, 2011

Check Back on Sunday

I am seriously, seriously behind here–we're cleaning off the deck for The Rapture–but I will get back to the Trickster conversation with a new post for those of you who are left behind (nobody in this household is going anywhere except Hell's Hamster Wheel so we're thinking a picnic Saturday at six with a good view of The End). Assuming the earthquakes and the fires don't take out the internet, I think we can pick this up again on Sunday. Oh, and for those of you who are good enough to go, we'll miss you. Kind of.

Feel free to continue trickster conversation below.

May 18, 2011

Trickster Help

Alastair and I were at lunch today–Steak N Shake, his reward for having survived another INS-mandated doctor's visit–talking about tricksters. If you've been listening to PopD for the past three weeks, we're all about the trickster hero*, what it takes to make a good one, how that kind of protagonist dictates his plot, etc. And somewhere toward the end of the fries we realized simultaneously that all the trickster protagonists we knew were male. You can have trickster female characters, but they're almost always antagonists and beyond that villains. The only female trickster protagonist I could think of in film was Julianne in My Best Friend's Wedding, and I had actively disliked her because she was selfish and ruthless, although, when I thought about it, I might have accepted a male hero who did what she did. Julianne made me actively uncomfortable because she was a female trickster. Even when I went to my own work, both of my trickster heroines, Sophie and Tilda, were trying to disavow that part of themselves, trying to be "good," which I must have subconsciously seen as necessary to make them likable or at least acceptable to me. My only trickster hero, Davy, was, on the other hand, mostly unrepentant. The shape-changing, boundary-crossing, unrepentant peace-breaking rogue is admirable in the male, not so much in the female.

At that point, we agreed that we needed to find some good trickster heroines (and I began to think about writing one, just because). Shortly after that, we drew a blank. So we're throwing the question out to you: Know any movies with a good trickster heroine?

* The trickster is an archetype that goes back centuries and yet is as modern as tomorrow. He's Mercury, he's Loki, he's Coyote and Raven, he's Brer Rabbit and Bugs Bunny, he's the Riddler and the Joker, he's Nathan Ford (from Leverage) and Danny Ocean, he's Bart Simpson and the Fool from the Tarot deck. That is, he's the guy who replaces your reality with his own using trickery and deceit, moving across boundaries, thumbing his nose at everything but his own code, upsetting the status quo; he's a shape-changer who transforms the world through his transgressions. One key aspect of the trickster is that although he is not necessarily a positive influence, usually (not always) he effects positive change. He screws things up because screwing things up is fun, but because he screws things up, the world is better for it. There's a lot of joy in the trickster stories because the trickster really likes being a trickster. That's why trickster stories are often funny; the trickster is a clown. But he's a smart, powerful clown which is why the laughter is often both spontaneous (I can't believe he did that) and respectful (it's so clever the way he did that).

May 12, 2011

Letting Go

I've been thinking about this a lot lately, the idea of letting go. It's an idea I'm remarkably bad at. Even when every fiber of my being is screaming, "This is a bad situation, this is wrong," I hang on. It's how I ended up married to the wrong man: we'd been together for three years, I wasn't going to just give up because I wasn't happy, of course I'd marry him when he asked. It's how I ended up doing all kinds of things I knew I didn't want to do, but by God, once I was in there, I was going to win. And then came Lyle.

Here's the thing about Lyle: he's not only going to die, if you look at his bloodwork, he's already dead. Forget the fact that he was chasing bumblebees last night and is rolling around on the bed play-fighting with Mona right now, his BUN number which should be between 7 and 25 is 165, and his creatinine which should be between .3 and 1.4 is at 9.8 (anything over 5 is end stage kidney disease). Those aren't just bad numbers, they're impossible. Our vet, who is wonderful, doesn't understand it and neither do I. And yet Lyle keeps on trucking.

Normally, this would be all I'd need to saddle up and save that dog. But the fact is, Lyle's going to die, and there is absolutely nothing I can do to save him. Nothing. All I can do is keep him comfortable and then when he begins to suffer, let go. I've tried to save other end stage pets. They stop eating and I force feed them, I medicate them, I get them operations, but the truth is, when it's time to go, animals let go. If I don't let go with them, it just prolongs their suffering. It is not a kindness, it's not smart or good, to hang on. The smart, kind, natural, good thing is to let go. I think that goes contrary to everything in our culture–we're Americans, we win at all costs–and in my nature. Giving up just feels wrong, not just with Lyle but with everything. But one of the greatest life lessons I have to keep learning is that everything has its time, and no matter how wonderful that time was, when it's over, it's over, and holding on just delays the next stage, whatever that is.

I'm thinking of it more and more because more and more I'm realizing that I'm coming to the end of my novel writing career. I hate that. I've had so much fun, it was so exhilarating, plus it was really lucrative. But the things that I want to do now are different, and while I'm shoving them aside to work on my novels, every instinct I have says, "This is not where you're supposed to be." Letting go of a great career is not easy, and I'm not sure I'm ready yet, I've still got books I need to write, but the blood counts on my novel-writing are going up like Lyle's.

Maybe it's not so much letting go as it is embracing change. Everything changes, everything evolves, everything turns into something else, and accepting that as good, even if it's incredibly painful, is the only way to move on to the next step, the next series of wonders. Letting go is only bad if you don't move forward with your eyes and arms wide open. Letting go of Lyle means losing him, but maybe there's something spectacular waiting for him around the bend. He'll never find that unless I let go. And I'm pretty sure there's something amazing up ahead for me, once I finish these books, once I think about where I could go and what I could do.

But, boy, this is not easy. Going to go cuddle Lyle now. Because I'm just not ready to let go yet.