Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 322

September 30, 2011

Let's All Go To The Vet

So Thursday was Vet Day, the day I mistakenly thought it would be faster and easier to take all five dogs to the vet at once. Thank God for Lani.

We got off to a bad start because I'd forgotten to round up enough collars and leashes for everybody, and then there was the hell of getting them all in the car (although Milton's always ready to go and so is Wolfie; it's Veronica who's sure it's a plot against her), and then the excitement of driving while Lyle bitched because he had to share his moment with the rest of the fam (he's used to solo trips and his own vet burger at the end, plus Mona chewed on his ear the whole way):

Then the fabulous time in the waiting room when they all ganged up on the Pomeranian who was evidently making your-mother-wears-army-boots noises, and then getting them all weighed while they checked out all the other examining rooms until we closed the door. (This is Lani and Wolfie. Wolfie feels the same way about scales that I do.)

Then there was general milling around and adoring Lani while each of them got stuff squirted up their noses and other indignities:

And then we all listened closely to what the vet said because we like her a lot, although I think what Mona is happiest about is being held by Lani . . .

. . . because it's obvious that five out of five dogs think Aunt Lani is the BEST:

Finally everybody was back in the car thanks to Aunt Lani who'd schlepped four of the dogs out while Wolfie was getting a dental looksee AND gone to Wendy's to pick up the ritual vet-burgers before Wolf joined his pack. Milton felt there might be something better outside, but the rest were just happy to be in a car with Lani and hamburger.

Then we went home and everybody got a Vet Burger and then we all took a nap. Well, I don't know what Lani did, but the dogs and I sacked out. Because Vet Day is exhausting. But the important thing is that we're all doing good including Lyle who continues to defy death and eat his own weight in mush.

Vet Day. Thank God for Lani.

September 26, 2011

Exploiting You Again: Wild Names

I'll get a real post up here as soon as I scrape myself off the floor. Quick updates: I turned 62, I'm back home, and that house I bought in NJ has to be completely gutted.

In the meantime, I need titles with "wild" in them. Shorter is better. Already used: Wild Night, Wild Ride, and Wild Child. So some more snappy two-syllable titles would be best although at this point, I'll take anything. I need three of them. No you're not going to see anything by these titles any time soon. The problem is taking up space in my brain that I need to write other things. So I'm moving it into your brains.

Braaaaaaaaaaaaaains.

Sorry. It's been a grueling month. And I'm old.

So, Wild Titles. Have at it.

September 12, 2011

On the Road Again, Bemused

So I'm on my way to New Jersey to close on the house (handing over a honking big check that will change my net worth to Not Much At All, Really). It's a two day trip because I tend to fall asleep after six hours, and even six hours is a lot when you have several stories playing in your head and you're trying to listen to all the voices. I took the same wrong exit today that I took two days ago for the same reason: voices in head.

(Also, I have the car packed to the gills with Stuff to put in the cottage which is going to be difficult because it already has Stuff: because I paid such a low price (comparatively speaking) for the house, I told them they didn't have to clean it out (they're in Arizona so it would have been the realtor who has been an absolute godsend through all of this). Which means I have to sort through the stuff. While moving some of my Stuff in. Which means day after tomorrow begins scraping up the sheet vinyl flooring, stripping wallpaper, priming every available surface, and in between, sorting Stuff. Yes, I'll blog the Stuff.)

But in the meantime I'm on the road, trying to pay attention so that I don't take the wrong turn or miss the sign that says "I-80″ after which it's a straight shot for 300 miles. I-80 is the PA equivalent of Ohio's 1-75 or I-71: long stretches of nothing except McDonalds and vaguely threatening religious billboards (HELL IS REAL) broken by insanely badly planned cities where a thousand different highways overlap, merge, court and spark. Yes, I'm looking at you, Columbus and Cincinnati, although Akron, you're no picnic, either. I have to pay attention driving through you all. Do you know how hard that is for a writer who finally has a book cooking in her brain, only to find there are two others in there babbling, too?

Here's how hard it is: Sweetness did not get off the bus on Friday. Lani grabbed Light and said, "Where's your sister?" Light blinked up at her and said, "I don't know. She wasn't on the bus." A couple of semi-hysterical phone calls later (Lani) with a background of pacing (Alastair) relayed the news that Sweetness was on the bus, she had just fallen asleep. I came into this at dinner:

LANI: NEVER EVER EVER EVER DO THAT AGAIN.

SWEETNESS: I didn't fall asleep. I was awake. I was thinking.

LANI: NEVER EVER EVER EVER DO THAT AGAIN. [Turns to Light.] And from now on you look for your sister. You SIT WITH your sister.

FAJ: Why is the younger kid looking after the older kid? Shouldn't it be the other way around?

LIGHT: Yeah.

LANI: NOT HELPING. [To Sweetness.] How could you miss getting off the bus? How? How?

FAJ: I do that all the time. I got off at the Lowe's exit the other day instead of at Eastgate. You're thinking, you miss things.

SWEETNESS: Yeah.

FAJ: It's a sign of her creativity. Same with Light. They have other things on their minds.

LANI: NOT HELPING.

FAJ: You do it, too, I know you do. It's probably your fault. You gave them that gene.

SWEETNESS: I love you, Aunt Jenny.

LANI: NEVER EVER EVER EVER AGAIN.

So okay, there was one day that Mollie didn't get off the bus (the mom who usually babysat her had sent her to another mom) and to this day I can't breathe when I think about it; I made Lani's reaction look understated. But still, this is a major factor in creativity: long stretches of time with a background going past rhythmically and nothing to do but keep the car on the road (or in the case of Sweetness and Light, nothing to do at all). I can't tell you how many major insights into stories I've had driving on 275. And missing exits.

So thank God for three hundred miles of I-80. By the time I hit the NJ border, I could have all the kinks worked out. Or I could miss a merge and end up in Canada. if so, I'm blaming Light for not watching me. It appears to be working for Sweetness.

September 4, 2011

Random Sunday

I lost my cellphone. I don't really miss it, but others do.

Lani and I went out to do Etsy shopping the other day. On the way back, we decided to get milkshakes. "McDonald's or Frisch's?" Lani said. (Our small town's choices are limited.) "Both," I said, so we got three small shakes from each place and took them home to Alastair to taste test. Unanimous decision: McDonald's. Not in the running: Steak N' Shake because it would have been no contest, those SN'S shakes are amazing.

Claire's has the best socks and sunglasses EVER. Plus Halloween jewelry. Great finds: a six pack of unmatched footie socks and clear-and-black checkerboard sunglasses with the sunglass part in a pink-rimmed flip up on the front. The spider earrings were the icing on the cake.

Speaking of cake, or a close facsimile thereoff: Halloween cinnamon rolls.

From Sandwich 365 which also has a terrific BLT costume for the whole family.

I read my horoscope. Evidently the end of the month is going to be really, really bad for me. (If you're a Virgo, start stocking bottled water.) Expect meeping. I know. "How will that be different from the rest of the days?"

Cleaning is much easier now that I'm moving. The question is no longer, "Do I still want this?" Now it's "Do I want to move this to New Jersey to a very small house?" Simples things up considerably.

For those of you wondering, Lyle is still doing fine. Lani's decided that he faked his blood test to get the mush. He's happily chewing up a cardboard box at my feet as I type. He is frumpy, his fur is bright red from the anemia, and Alastair sticks a needle in him every night and fills him full of saline solution, but otherwise he's fat and happy. His life may end at any moment, but in the moment, it's grand.

Alastair, by the way, is still dumbfounded by the weather: in the mid 90s yesterday, 63 today. "Adapt," we tell him, but he's still bitter about that earthquake.

Did anybody else see the Burn Notice episode about the guy who took his son to the survivalist camp? If so, did you have the same WTF? reaction I did to the way they ended that? The writing this season has been sloppy, but that was . . . what's the word I'm looking for? Two words: Truly Abysmal. Reminds me of the Jack Armstrong Tiger Pit story.

Jack Armstrong was a radio serial back in the first part of the 20th C and every episode ended on a cliffhanger. So one night, Jack Armstrong is surrounded by his enemies, outgunned and outmanned, with his back to a pit of tigers. At the end of the episode, Jack leaps into the tiger pit! How will he survive? Next episode begins, "After Jack Armstrong got out of the tiger pit . . ." Burn Notice: Jumping the Shark into the Tiger Pit.

It's a wonderful thing to renovate a cottage. People suggest all this expensive stuff and you say, "It's a cottage." Expensive stuff would look DUMB in a cottage. Which is good because I don't have a lot of expensive stuff. But I may go for Big Chill appliances when I eventually do the kitchen. Since I'm painting the floor and using shelving instead of overhead cabinets, the cost might come out the same. Maybe. Those suckers are expensive.

Speaking of bad seasons, Leverage is breaking my heart. When I started watching the funeral home one with Hardison in the coffin screaming and the screen said, "Two weeks earlier," I just turned it off. I hate those damn flash-forward beginnings; they're lazy, stupid writing. And now Leverage is doing it. Plus they seem to have lost that sense of fun that made the capers so compelling. I'm seriously close to dropping it, even though the first two seasons were stellar.

Lani has decided to make Sugglies for the Etsy store: Seriously Ugly Socks that have magic powers. She needs a tagline but refuses to give me one. The idea is that they're low-rise Mary Jane socks that can't be seen with shoes on, but that give the wearer incredible power with their ugliness. Or something. Lani? Come in here and explain that again.

So tonight we're buying Going Postal from iTunes and watching it while we eat fajitas (not quesadillas, got that wrong) and milk chocolate brownies while we knit (Lani), crochet (me), and discuss how the old Romans did it first (Alastair). Then we all go back to work.

That's what I call a truly random Sunday.

September 2, 2011

OMG: Going Postal on DVD

Not being British, and evidently having NO FRIENDS IN BRITAIN*, I have just discovered there was a Going Postal TV movie last year and it'll be out on DVD on Sept. 20. And Richard Coyle (better known to me as Jeff from Coupling) is playing Moist, which makes me a little dizzy with happiness. Also Claire Foy as Adora Belle and a cameo from Terry Pratchett, my go-to cheer-up guy-author, as a random postman. Oh, my God. Oh, my GOD, OH MY GOD! As Lani would say. This is one of the best books Terry Pratchett ever wrote, which means it's one of the best books ever written and now they made a movie out of it with Charles Dance as Vetinari and David Suchet as Reacher Gilt . . .

I have to go lie down for awhile. In the meantime, here's a preview:

And here's Pratchett talking about the story and the movie:

I'm pre-ordering. Because . . . oh, my God, GOING POSTAL on DVD!

*I mean, honestly: Strop, Ag, and MY BROTHER-IN-LAW WHO LIVES WITH ME, all forgot to mention this? Although Strop gets a pass because she sent me Hogfather. Still, this is MOIST. Sigh.

August 26, 2011

Good Luck, Eastern USA

Hey, we have Argh People in the path of a hurricane. For them I offer this. Please stay in touch and report in with any cool hurricane stories. I slept through the earthquake in Ohio so I had nothing to share, but Alastair did not. He went upstairs to Lani and said, "What was that?" She said, "Earthquake." He said, "Floods. A hundred-degree-plus heat. Earthquakes. You couldn't mention this before I emigrated?" Or words to that effect. Actually what he said was funnier. If Lani logs in here and gives me the actual quote, I'll change it.

In the meantime, you right-coasters, be careful out there.

August 19, 2011

Not Such a Dumb Idea, After All

So we had the home inspection yesterday, along with geothermal people who came to look at the feasibility angle. All expressed the same things I did the first time: the place is really hard to find, and it's a little run down (ohmygod it's derelict). By the end, the geothermal guy was explaining he'd be out personally to do the yearly inspections (and be bringing his fishing pole) and the inspector was more enthusiastic about the house than I am (and I love it). The foundation is rock solid–probably because it's on rock–and all the walls and windows and doors are still on true, even after sixty-five years on a lake. All the problems are easily fixable and the roof is good for another three or four years. Or as he said as he left, "This is a great house."

Then I spent the rest of the day measuring and drawing up a floor plan. I've got one now that's mostly right–may be off in places but gives me the basics–and today I get to see my grandkids. Also my daughter and son-in-law which is always nice, but let's face it, it's the grandkids. We don't close until next month, and I never believe anything is going to happen until it's a done deal, but basically, cottage-at-the-lake-see-my-grandchildren-all-the-time-go-to-NYC-whenever-I-want-no-mortgage . . . this was a brilliant move on my part. Who needs a retirement fund? (Well, I do, but I need this place more.) So :p to all the naysayers.

I've got vision, that's what I've got.

Heres a better picture of the back of the house, without the chainlink fence in the way.

Edited to add:

View of lake as Susan requested. It's a LONG way down:

August 15, 2011

Retail Therapy

I'm not sure why buying things cheers me up. I already have more crap than anybody else on the planet–the joke here is, "Don't ask Aunt Jenny if she has something, ask her where it is"–plus I'm broke. But this week I found cheap stuff (rule: must be under ten bucks) that made me smile. And here's the thing: according to several different places on the net, smiling relieves stress, lowers blood pressure, makes you more attractive to others, boosts your immune system, and is a natural painkiller. So as long as the stuff that makes me smile is under ten, I figure I'm getting a deal. Do you know what therapy costs?

I found a one-hour hourglass timer at T.J.Maxx for $9.99. I'm using it to kick start the writing every day. "You just have to write until all the sand is in the bottom."

Beats any digital timer and makes me happy at the same time. There's something so soothing about all that sand slowly falling . . .

iTunes has forty Drifters songs for $9.99. It's the All Time Greatest Hits and More (1959 to 1965) by The Drifters.

The Drifters may be my favorite group of all time–they're always in the top five–because their music makes me insanely happy (". . . something happens to me that's some kind of wonderful . . .") and I can get their songs for a quarter each. Whoa, Nellie, I'm there.

I was searching for pins on eBay (don't ask, it's for a project) and I found this one:

Gertrude looks like she doesn't take any crap from anybody, kind of a German Mona.

She only set me back $9.49 including shipping, fifty cents under my limit. I figure she'll make me happy every time I look at her. Even if that's only ten times, that's less than a buck a smile. DEAL.

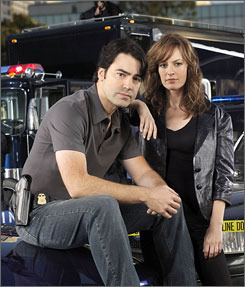

And then there's Standoff, one of my all time favorite TV series which unfortunately only lasted eighteen episodes (morons cancelled it) but all eighteen are available on Hulu Plus along with a ton of other stuff for $7.99 a month.

It's Ron Livingston and Rosemarie DeWitt (fun fact: they met on the series and got married three years later) as hostage negotiators who are also lovers. One of the smartest things the series did was begin after they'd slept together, three months after, as Matt announces to the world in the first episode (which was dumb and out of character but I went with it anyway). I love the way they layer the relationship with the hostage negotiations–as Emily says, "At the heart of every crisis is a broken relationship"–and I love the smart ass humor and great chemistry. (One of my fave moments is when Emily is trying to explain how things have changed to Matt, and tells him it's like crossing the border between Portugal and France, everything's different. Matt says, "You know Portugal and France don't share a border, right?" And she says, "I know, but what do you think? What are you thinking right now?" And he says, "I'm wondering if I'm going to get into Portugal tonight.")

Eighteen great episodes, Ron Livingston and something to smile about in every one. Bonus: Hulu Plus means not bringing more actual stuff into this house.

Speaking of having too much stuff, I mentioned to Light that my drawing paper was in the studio. She said, "There's a studio?" I said, "You know, that big room off the office. The one with the pool table." She said, "We have a pool table?" Sometimes you don't have to buy stuff, you just have to dig it out.

Oh, and I also bought a house in New Jersey. It has no poles but it's also derelict with a mold problem. Or as Gaffney said, "How much did they pay you to take it?" If nothing goes wrong, we close in September and I'm the owner of a lot of mold with attitude. It was more than $9.99, but as I said, no poles.

It may be awhile until I'm back here again, but I am doing better, and I'll go back through all the comments next week when I'm on the road and we'll revisit coping strategies. One key thing: I've figured out what was wrong with my book–very excited about it, as a matter of fact–so I'm going to go turn over my hourglass and put The Drifters on and maybe get a picture of Ron Livingston for my computer, and then finish a book. Nothing but good times ahead.

For $9.99.

August 7, 2011

"We Just Have To Learn How To Get Through These Very Bad Days"

That title is from Beth Henley's Crimes of the Heart, from the scene where Meg pulls Babe's head out of the oven when she's trying to kill herself. Meg asks why, and Babe says something like "It was a very bad day," which is the reason they'd all given for their mother hanging herself in the basement. And Meg says, "We just have to learn how to get through these very bad days."

This is a skill I must master.

How bad did it get? I was bringing Lani home after dropping her car off at the repair shop again–that car must be completely rebuilt by now–and we were both depressed as hell, but as she got out, she turned to me and said, "It's all going to be all right."

And I looked at her and said with absolute sincerity, "No, it's not."

Yeah, ol' Nothing-But-Good-Times-Ahead finally hit bottom.

I think it was just a perfect storm of things and it knocked me off my game. I know how lucky I am–hell, I have a JOB–but there are so many uncertainties that I'm having a hard time finding a safe place to stand. Sometimes you just need to hold onto one thing that's sure and safe, and if you can't find one thing that's not up in the air with the potential for disaster, well, that makes it hard to breathe. Add to personal stress the knuckle-draggers in Congress who have managed to trash the US credit-rating while protecting the rich, and the general ass-hattery of politics in general, mixed with the horrible jobs and real estate markets, and I needed a cookie badly.

Of course I could have come back here and posted about how depressed and anxious I was, but really, who the hell needs that? I'm one of the luckiest people I know, who am I to bitch about a few setbacks? If I don't have anything to contribute, I should just shut the fuck up. So I shut the fuck up. Hence the long silence.

Now things have shaken out a little and I'm coming up for air. I've hung on using my general coping tactics–music, crochet, chocolate, dogs–and I've got some good stuff to look forward to now–you need some good future coming up even if it's little stuff–but I'm not out of the woods yet, and neither, I'm betting, is most of the country.

So here's what I want to know: When you start going down for the third time, not just "I've had a bad day" but "No, it's not going to be all right," what do you do? Drugs are out, addictive and expensive, and probably shopping, too, for the same reasons. What's a cheap, easy, effective coping tactic for getting through the very bad days (weeks/months . . .)?

Because my oven is electric, so that's not a solution.

July 24, 2011

Random Sunday: The Cranky Edition

People are thwarting me. I understand that they think it's for my own good. In fact, it probably is for my own good, they're probably right. I fail to see what that has to do with the fact that I WANT something. So today's Sunday is Cranky.

Alastair reached in the fridge and gave Lani a Diet Coke. "I love you," she said. "I love you," he said. "Jesus Christ, do you have to do that in front of me?" I said. "Haven't you developed immunity yet?" Alastair said. He's missing the point. If she has just insisted that he stay in bed because he's sick and then waited on him hand and foot, "I love you" is allowable. If he rescues her from a speeding train and they fall into each other's arms, the "I love you" is understandable. If he gets her a Diet Coke, "I love you" is icky. Because this week, I am Cranky.

My daughter was trying to explain to me that looking for a house to buy is a long process. I said, "I've bought four houses and you've bought one, and you're telling me how to do it?" That was wrong of me, she was trying to help and encourage me. But this week, I am Cranky.

Most of the dogs are pretty well-behaved or at least know that "No" means "try that again and the wrath of the Pack Leader will descend on you in all its fury." But Lyle, who's been spoiled rotten for five months because of his imminent death, lost that bit of knowledge, so when I opened up the door and said, "No," meaning, "do not dash through this door at any cost," he dashed. I yelled so loud he tried to crawl under the bean bag. He's doing pretty good with "No" now. I'd feel sorry for him because he probably only has days left (or at this rate, years), but this week I am Cranky.

Lani and Alastair and the kids came back from the Y, rained out. Lani said, "Who knew?" I said, "Anybody who looked at AccuWeather; it's going to pour here for three days." She said, "I'm going to get you a T-shirt that says, 'It's your own damn fault.'" She's already planning on getting us matching T-shirts; mine will say, "I'm not mean, you're just a sissy," and hers will say, "I'm not sensitive, you're just an asshole." Sometimes we are both Cranky.

I have a new laser printer (because my old workhorse HP that I LOVE refuses to talk to my laptop) and I tried to register the damn thing and kept getting error messages. Because all the letters have to be in caps. And the thing I thought was an O was a 0 (oh and zero). Then it wanted the date I bought it, but I didn't know the day, so I put in month and year. Incomplete. So I made up a day. Not according to format. What format, there's no format on the site. So here's my point for Brother: if you're so damn desperate to have me register, why are you being such a putz about it? Also, no I do not want to get updates from you. I've had it with you. And not just because this week I am Cranky. OTOH, it's a nice printer.

And then there's Word. When I open it, it insists on giving me a window to help me choose the kind of document I want. If I hit cancel, it gives me a document anyway. Microsoft: More controlling than my mother.

I had more, but then I saw these pictures on Gawker and wept like a baby, "ugly crying" as Matt Cherette says, and now all the cranky is gone. I heart New York and its very smart courts. Congratulations to everybody there who can finally marry the people they love! I'd say more, but the pictures do it better and I have to cry some more. God, I love a happy ending.