Tim Mathis's Blog

October 24, 2025

Life after the PCT: Thru-hiking was the best career decision I ever made.

August 26, 2025

Hate America and feel trapped? Have you considered trying 19th century philosophy?

August 14, 2025

How the PCT Made Me an Accidental Modern Transcendentalist (and why you might care)

March 22, 2025

Thru-hiking: Pilgrimage While the World is Burning

October 7, 2024

The Wind River High Route: A 7 Day Traverse

September 22, 2024

The Wind River High Route: What you need to know before you go

There are plenty of writeups of the Wind River High Route experience. I’ll eventually add my own, but for this post I want to do something a bit different: I want to provide a concise guide to everything you should know before you embark on the route. I’ve included links to more comprehensive resources where needed. Think of it as a quick and dirty introduction to the essentials.

Big thanks to my old friend Six2 who figured all of this stuff out before our trip so I didn’t have to.

Confusingly, there are two popular routes that people refer to as the Wind RIver High Route. One was designed by Andrew Skurka, and one was designed by Alan Dixon. Both pass through the alpine zone (that is, above treeline but below snowline) in the Wind River Range in Wyoming. Both are primarily off trail-thru hikes. Both have some similarities to the Sierra High Route in California, but are often considered more remote and spectacular, if not more difficult. Both stay close-ish to the Continental Divide. They overlap in places making it slightly more confusing.

It’s less confusing when you understand that really, both are just guidelines for a “choose your own adventure” week in the Winds which provide a path to access the remote core of one of North America’s most beautiful ranges.

For full disclosure, I haven’t done most of the Skurka route. My friend Six2 and I stuck primarily to the Dixon route when we hiked in August of 2024. My Skurka information here is drawn from multiple other hikers’ experiences.

This site has a fantastic, comprehensive comparison for those trying to decide on which to follow.

Skurka’s route is longer, sketchier, and harder. It’s a serious challenge. It is also arguably more scenic, because it stays higher in many places, and traverses two thirteeners at the start and finish of teh range that Dixon’s doesn’t cover. It opts for a more glaciated terrain in the north, and requires a bit more scrambling. His route is approximately 97 miles and generally takes experienced, fit hikers 7 - 9 days to complete. He recommends traveling from south to north.

Dixon’s route is shorter and less hard, and therefore more popular. Don’t read “less hard” as “not hard.” It is still a serious challenge for the vast majority of hikers. It is still long and sketchy. It still requires a significant amount of scrambling and boulder hopping, and includes a short but significant glacier crossing. It is approximately 83 miles and is designed to take 7 days. You still need to know what you’re doing. He recommends traveling from north to south.

There are plenty of places where the routes parallel or overlap, so you can switch between at different points.

In both cases, mileage is almost beside the point, because terrain, elevation change, and weather are what determine your pace as much as distance.

Skurka wrote a guidebook with his route that you can (and should) purchase, which gives a ton of beta, which is very useful. It also includes shorter loop options if you don’t want to do it all in one go. Dixon has posted his route information for free online. It is slightly less comprehensive and isn't kept as up to date as Skurka’s, but you should still review it and consider downloading his maps.

The views speak for themselves:

It’s a real epic. I’m not the most experienced hiker in the world, but I’m sure that I have hiked more than 5000 trail miles now across the US, Canada, New Zealand, Europe, and Latin America. I’d go so far to say that The WRHR is the hardest, best week of hiking I’ve ever done. It’s transcendent.

For a certain type of person, at a certain stage in your hiking career, it’s exactly the sort of challenge you need, and it rewards you with a period in wilderness that is as spectacular as any on the planet.

Neither of these routes are for beginners. This is a thing to do if you are fit, know how to boulder confidently, have at least one person in your group who is confident and experienced in off-trail navigation, at least one person with basic glacier travel experience, and are comfortable with being in the mountains on your own, days from civilization. Most people who do this, it seems, have completed previous long thru-hikes, have prior experience in big mountains, and are looking for a real challenge. Technical climbing experience is useful but not required.

If you’re that person, this should be at or near the top of your list. With the right skills and a decent level of fitness, this is maybe the best way to spend a week in the mountains in the entire United States.

The WRHR is mostly off trail and is not on signed path. You have to be able to figure out which direction to go yourself. You also need to be able to make safe terrain choices in a variety of conditions. This is relatively straightforward most times because of technology. Carry GPX on your phone with a backup battery (links below). If you haven’t used a mapping app before, familiarize yourself with whichever one you choose (They’re a bit trickier than FarOut, etc. which a lot of thru hikers use). Carry paper maps as a back up because you’ll be out there for a long time in potentially bad weather. If you don’t know already, learn how to read topo. It’s useful to do a bit of orienteering if it’s an option where you live.

I will say that, generally speaking, navigation is straightforward on this route because you’re above tree line and able to see across distances in most cases (assuming the weather isn’t socked in). However, if you’re like us, you may end up hiking after dark or in sub-par conditions, so having multiple resources to draw on (i.e. GPX and maps) is really useful at times. There are plenty of opportunities to get cliffed out on steep terrain here, or to accidentally waste hours heading up the wrong pass.

I will also say that there was a fair amount of established tread on the route, because plenty of people do this. However, it was rare to find good trail for any extended period - even where it’s on the map - particularly between Indian Pass and the base of Sentry Peak Pass. This route is not maintained.

Both Skurka and Dixon describe their routes as “non-technical,” but what does that actually mean? It doesn’t mean that you’re just walking. Both routes involve a stream of boulder hopping and scrambling, and cross a few spots of exposure to serious falls if you slip. You’ll spend a good amount of time navigating loose scree and boulders, often on steep angles. You’ll cross at least one crevassed glacier. you probably won’t need an ice ax unless you’re going in a big snow year or early season, but you will be on a high enough angle that microspikes are required for safety (NOT YakTrax - actual spikes). A lot of days, we moved about a mile an hour. You might go faster, but be prepared for much slower movement than you’re used to on trail.

On Skurka, there are a couple of class 3/4 scrambles - which means basically that you don’t need a rope to climb it, but if you fall, you might die. On Dixon’s original route, there’s one class 3/4 scramble, but this is avoidable if you take an alternate route around a lake (this is clearly marked on his website).

On both routes, there are a lot of places where injury is very much a possibility. Both routes “go,” but you need to be confident bouldering and rock hopping in a heavy pack, and have appropriate gear (spikes and poles) for brief periods of glacial travel.

Dixon’s route stays between 10 - 12,225 feet the entire route. Skurka’s is between 10 - 13. The optimal time to acclimate if you’re coming from sea level is 3 - 5 days.

Due to snow patterns, most years the route is only accessible during the late monsoon season, between late July - early September. Monsoon season means frequent thunderstorms, generally in the afternoon (although this is less predictable than further south in the Rockies). Early snowstorms can hit in August, although snow is highly unlikely to linger until mid-September. You’ll be above treeline most times, so you’ll have a lot of exposure to the elements. The terrain is slow going, so it’s often not easy to drop down during a fast gathering storm. Wyoming is relatively dry in the summer, and you might get lucky (like we did) and catch a clear week, but you need to be prepared to get seriously hammered by wind and rain.

The route can be mosquito hell if you go shortly after the snowmelt and hatch. July can be really bad. Early August can be really bad. Late August/early September are best.

We saw a lot of people on the first day and the last two days of our trip on the Dixon route. In the middle we saw maybe 1 - 2 parties a day. You’re on your own out there for the most part.

Dixon is designed as a 7 day route. Skurka can take 9, even for fit hikers. There are no road crossings. You have to carry a lot of food.

I’ve heard you can hire outfitters to do food drops midway so you don’t have to carry so much. It isn’t a terrible idea if you don’t mind spending the money. We didn't use them ourselves, but I hear the folks at Stetter Outfitters can help.

Theoretically the Winds are Grizzly country (particularly in the north) but up high, an encounter is not at all likely. I’m not sure there have been any recorded Grizzly encounters on the High Route. I couldn’t find any with a quick Google search. Entering and exiting the Winds are the most likely places for a bear encounter but even then it’s not likely. Black bear are more common and visible, but the route generally stays above their range and outside of their territory. There are brief periods in bear country, so we carried spray mostly as a talisman against them. We put our food in Ursacks and typically did not camp where we ate, just to be safe. We had no encounters, but we did see pronghorn, elk, and moose - all at a distance. I also saw a curious pine marten, and a bunch of marmots squeaked at us.

The best window is usually the last two weeks of August through the first week of September. Most years, this is the best timing to avoid the mosquito hatch, and to sneak in after monsoon season peters out and before the snow starts again in the autumn.

I don’t want to scare you off, but I do want to give a good rundown of the actual risks on this route, so you can be prepared and avoid them. What do you actually need to be worried about?

To me, the highest risk has to be rolling or breaking an ankle because the route involves constant boulder hopping.

Similarly, loose rock is a serious risk, particularly ascending and descending passes. You traverse a ton of talus, much of which was recently deposited by glaciers and is big and mobile and dangerous. Triggering rock fall or losing your footing is a frequent possibility.

A fall or uncontrolled slide on the Knife Point Glacier could lead to serious injury. (Once again, carry microspikes.)

Getting lost or off route would be easy if you don’t know what you’re doing when it comes to navigation, or don’t have good GPS guidance and maps. The best advice is to carry GPX tracks on your phone and paper maps, and to research bail out routes beforehand (there are a fair number but distances are large).

The elements. Exposure to rain/hail/lightning/snow is likely. Be prepared with good rain gear, warm base layers, and shelter.

Altitude sickness. Altitude combined with exhaustion can end your trip if you’re not acclimated.

As long as you do your research and stick to the advised routes, you probably won’t die on the WRHR, which is nice. Even if you’re experienced though, you absolutely could get injured in a way that will make it very difficult to self-extricate. Take a rescue beacon. Be prepared. A rescue could take 24 hours or more, particularly if the weather is bad.

Most of the route was of similar difficulty, however there are a few key crux points on both routes.

Skurka:

According to Climber Kyle, Douglas Peak Pass after Alpine Lakes is one of the hardest portions - with loose scree an rocks on a steep slope making for an unpleasant experience.

General consensus is that Europe Peak is also a key challenge as a class three scramble, an anxiety provoking knife-edge traverse, and exposure.

Finally, most people seem to agree that the worst part of the Skurka route (including Skurka himself) is the West Gully below Wind River Peak at the south end of the route. Like with Douglas Peak Pass, this involves very loose, very big rock on a steep grade. It is longer than Douglas Peak Pass, with about 2000 feet of this sort of terrain. People we met along the way told us that it made them seriously question their life decisions.

Dixon:

On Dixon, the only section that is rated as class three scramble is at the outlet for Lake 10895 (aka Middle Alpine Lake) in the Alpine Lakes Basin. Dixon's original route sent you around the north side of the lake and then down a 75 - 100 foot section of mess. This can be avoided (and I’d imagine most people do) by going south of the lake. That’s what we did.

For us, the descent on large talus from Indian Pass, and then across Knife Point Glacier, was one of the more sketchy sections due to big, loose rock, and then crevassed glacier. It’s doable, but I wouldn’t want to attempt it without spikes.

On both routes, the traverse around Alpine Lake is (surprisingly) perhaps the slowest going section of the entire trip. The topo looks fine. There’s just one scramble that looks sketchy from a distance but wasn’t actually that bad (well marked on Skurka’s GPX and Dixon’s map). But the cumulative effect of rock hopping and scrambling adds up to very slow progress. Many people on Dixon do Indian Pass, Knife Point Glacier, Alpine Lakes Pass, and the Alpine Lakes basin as one day, aiming to camp at Camp Lake. This is what we did. It took us 13 hard hours to go less than 10 miles. It was by far our slowest, most difficult day.

It’s funny that I haven’t covered this yet, but here are the terminuses of the routes:

Skurka (typically hiked south to north):

Bruce Bridge Trailhead in the south

Trail Lakes Trailhead in the north.

Dixon (Typically hiked north to south)

Green River Lakes Trailhead in the north

Big Sandy Trailhead in the south.

How do you get between them?

There’s a paid shuttle for the Skurka Route from Lander.

There’s a paid shuttle for the Dixon Route from Pinedale. (They also do car shuttles.)

If you’re doing the Dixon route, and don’t want to pay for a shuttle, it is reasonable to hitch from Pinedale to Green River Lakes Trailhead at the start, then hitch from Big Sandy TH to Lander at the finish. Both are popular, busy trailheads. Even though they are quite a ways out - hours from town - and may require multiple hitches, plenty of people get there this way.

If you’re doing Skurka, from Lander you can hitch to the Bruce Bridge Trailhead. Then, from the Trail Lakes Trailhead, it’s about a 10 mile hitch (or walk) on gravel road to Dubois. These are typically a bit easier hitching than the Dixon trailheads.

If you have multiple people with multiple cars in your party, you could of course do a car drop.

To get to the area, assuming you aren’t driving, you can fly to the Central Wyoming Airport in Riverton, then take a bus or hitch to the nearby town of Lander to access shuttles as needed.

If you are doing this route as a Continental Divide Trail Alternate (as we were), the Dixon Route is intuitive because the signed CDT connects with it both at the northern terminus (Green River Lakes) and very near the southern (Big Sandy). You can get creative and connect with Skurka, but it takes a little more work.

So, I’ve covered a lot of what you need to know. What do you need to DO?

Buy and read Skurka’s guide and GPX track notes (He does NOT include a ‘red line’ GPX track, but does include notes on various crux points that are very useful - particularly if you’re attempting his route vs. Dixon’s.)

Overview Dixon’s route (I saved the webpage offline so I’d have basic beta every day.)

Download GPX from CalTopo.

Decide which line you want to take beforehand, and familiarize yourself with crux and bail points.

Get the right gear: Everyone has their preferences, but this post includes a good list if you’re trying to make sure not to forget anything. A few notes from our experience:

Carrying an InReach with texting capabilities and the ability to pull weather reports was really helpful. You’re out there for a while, and you can’t really trust forecasts more than a few days ahead in the mountains. Pulling up to date, location specific weather is more useful than going on whatever the guess was in Pinedale or Lander a week prior.

Carry decent microspikes - not just YakTrax.

Carry a tent that can handle heavy wind and rain. You don’t need a mountaineering set up, but also be ready for serious wind gusts and potential heavy storms in exposed conditions.

Footwear should be sturdy but you can think hiking vs. mountaineering. I wore Brooks Cascadias, and they were great.

Sunscreen and chapstick! The sun is harsh and constant. The wind is harsh and can be constant. My lips and skin were a cracked, chapped wreck by the end of the week.

You don’t need a bear canister, but an Ursack is a good option. There are a lot of animals, and it’s a safeguard against rodents and porcupines and so forth as well as less likely encounters with bears. It would suck to have a mouse in your food four days into the wilderness.

Don’t stress too much about water. It was plentiful, which is great. Up and over some of the passes there were an hour or two between sources, but otherwise it seems like it’s everywhere. I don’t think I ever needed to carry more than a liter. I used a Sawyer filter to purify. Six2 used AquaMira. Both worked. Probably the water up there is as safe as you’ll find anywhere in the States.

On the Skurka route, a section of the trail passes through Wind River Indian Reservation land - between Photo Peak and Middle Fork Lake. It’s a nice section and I recommend it (it's a good, accessible option even if you're doing Dixon), but you do need to pre-plan and get a permit. At time of writing, I believe you have to buy it in person, but there are several locations where you can do so in Lander, if that’s where you’re starting. Here are useful instructions.

Review other hikers’ experiences.

I’ll link you to my own writeup once it’s finished.

I like Kelly Floro’s write up from The Trek on the Dixon Route for photos and advice.

I also liked Alison Young’s more comprehensive write up on the Dixon route.

Climber Kyle writes up the Skurka route well with great photos for the strong climber/hikers out there. (They moved much faster than us. They completed the Skurka route in 7 days, which is at least a day faster than most.)

Get fit. I did a tune up hike on Te Araroa for two weeks in February, then went to the gym regularly for 2 months. Then, we hiked for three weeks from Big Sky Montana on Continental Divide Trail alternates before we got to the Winds. You maybe don’t need to do all that, but you should plan to go in with a good level of fitness.

Get acclimated. How long does this take? It depends, but ideally 3 - 5 days, they say, sleeping at altitude.

Before you start, check your conditions.

Get a good mountain weather forecast for the range (not just the nearby towns).

Get up to date information on that year's snow levels in the range, and glacier conditions if possible - especially if you’re planning an early trip - i.e., in July.

Check data on wildfires. It’s not likely to impact your travel up high, but down low fires can impact bail routes and trail access.

Seriously, the whole thing. Nowhere was boring. Everywhere was beautiful.

If you’re an experienced long distance hiker looking for a real challenge in scenery that you’ll never forget, put in the work and do it. It’s completely worth it.

Feel free to shoot me questions if you have them!

Want to know what it was like for me? Want to see a lot more photos? Stay tuned for my story about our experience. Subscribe to the mailing list on the homepage and I"ll let you know when it's live.

May 10, 2024

Running the Camino de Santiago: Everything you need to know.

This post is focused on the running-specific information you need for the Camino de Santiago. For a comprehensive guide to the trail, check out my book The Camino for the Rest of Us .

What is the Camino de Santiago?

What are the most runnable routes?

What's it like, running the Camino de Santiago?

FAQs (that runners don't need to worry about)

If you're a runner looking for a genuinely grand adventure, there's no more accessible option than the Camino de Santiago.

It’s a world-unique opportunity to run across an entire country without navigating complicated logistics, and with the flexibility to approach it however you'd like - whether you’re a 5k newbie or a seasoned ultra runner. Multiple Camino routes across Spain make a weeks-long journey almost unbelievably straightforward, and the options for varied terrain and cultural experiences are remarkable.

If you’re traveling in the summer, on the Camino you don’t need a tent, a sleeping bag, a sleeping mat, more than one change of clothes, cooking gear, or storage space for more than a half day’s food. I know from experience that you can fit everything you need into a small running pack. You can run as far as you'd like every day, and you can resupply at a variety of locations along the way, no planning required. It’s simply the world’s least complicated place to go on an extended adventure run.

If you're here, you probably have an idea of what the Camino is, so I'll keep this short.

"The Camino" is not actually any one thing. It's a network of trails and marked routes extending across Europe and terminating in Santiago de Compostella in western Spain. Santiago is the purported burial place of St. James' bones, and is a traditional pilgrimage destination that has drawn pilgrims for more than a thousand years. The routes still draw a percentage of religious pilgrims, but nowadays most people walk the Camino for personal or cultural reasons.

However, when most people talk about "the Camino," they're referring specifically to the Camino Frances. This is the most traditional route, running about 780 km between Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in western France and Santiago. The Frances is by far the most popular Camino, although multiple other routes have also grown up in recent years (more on that below).

What are the most runnable Camino routes?

What are the most runnable Camino routes?

Santiago Ways has a slightly more detailed breakdown, but in short, the popular Camino routes that are most amenable to running include:

The Camino Frances, which stretches 780 km from the French border to Santiago.

The Camino Ingles, which covers 122 km from Ferrol on the northwestern Spanish coast to Santiago.

The Camino Portuguese. There are multiple Camino routes through Portugal, starting in Lisbon and terminating at Santiago. The distance from Lisbon is 620 km. However, the majority of people start in Porto and do a shorter portion - either 280 km along the Coastal Camino Portuguese, or 244 km along the Central Camino Portuguese. (I wrote up a complete guide to the Coastal Camino here.)

The Camino Finistere, which covers 90 km from Santiago to Finisterre on the Galician coast, or 115 km if you add a connecting route to Muxia.

On all of these routes, accommodation, food, and medical care are readily available at easy intervals the entirety of the way, and terrain is straightforward.

The Camino del Norte (825 km) and the Camino Primitivo (321 km) can also make good options for runners, and can be combined to create arguably the most beautiful Camino route in Spain. However, logistics are slightly more complicated. Distances between towns tend to be further and terrain more difficult, which translates to heavier packweight from day to day.

My wife and I ran the Camino Frances and the Camino Finisterre - 500 miles between the French border and the Atlantic. When we set out, I was worried about what we were getting into, and whether the trail would actually “work” for running. By the end of the first day, we’d established a simple routine that we followed the entire trip.

For us, every day on the Camino followed the same pattern: Wake up in an albergue (the Spanish name for a hostel) surrounded by other pilgrims. Leave around 8 am, and run until we find a cafe for breakfast. Eat a chocolate croissant and a cafe con leche. Run some more. Stop for Coca Cola or fresh orange juice. Run some more. Eat lunch - a sandwich and fruit in a cafe, usually. Hike until lunch settles, and then run to our destination - usually finishing at about 2 PM just as the heat of the day is setting in. Shower and wash our clothes. Grab a beer or two. Wander in a quaint village or talk to other pilgrims. Go to sleep, crashed out despite the snoring and smells.

We repeated that pattern for a month, and it was amazing.

I would describe the terrain as primarily “rolling” on all of the popular Caminos. There are mountainous regions in the Pyrenees and Galicia, but the the elevation changes aren't outrageous. There are a couple of climbs in the range of 2 - 3000 feet, but those extend across long miles. The grade is typically akin to railroad grade in the US, so it’s rare to find any extended periods that are genuinely steep (at least from the perspective of an experienced hiker or trailrunner). The tread is mostly dirt or gravel road, with some amount of asphalt and cobblestone in the towns. There are very few places on any of the popular routes where the Camino could be described as rugged. (The Norte and the Primitivo are typically seen as the most challenging.) These are rural routes primarily - not wilderness treks. That said, it’s beautiful countryside packed with history and culture. You’ll travel the entire way without seeing the same thing twice, so you’re unlikely to get bored. You pass multiple small towns most days, and most of the routes also go through major cities.

A general way to think about a run on the Camino is as a series of shorter stages between albergues or other accommodations. On all of the routes, these are typically spaced between 5 - 25 km apart (i.e. 3 - 15 miles). You can complete as many of those stretches per day as you like.

While the documentation is unclear, the fastest anyone has run the entire Camino Frances is in the range of a week, but the experience could be drawn out for months if you prefer.

We weren’t particularly ambitious, and our itinerary was not dissimilar from many hikers - between 20 - 30 km/day. We did complete a 50k day into Burgos, and ran 85k of the Camino de Finisterre in one push. The entire 500 mile trip took us 33 days.

Our original planned itinerary on the Frances is linked here if you’re interested. This allowed us to have fun, move at a relaxed pace, and minimize our risk of injury. We were normally the last pilgrims to leave the albergues in the morning, and among the first to stop in the afternoons. It made for an incredibly enjoyable experience.

There’s no real barrier to approaching things however you’d like. If you want to mix running and hiking, you could pack light, run 5k - 10k a day and hike the rest. If you want to set a record and do 800 km in a week, go for it! A beautiful thing about the Camino is that there’s no single way to have a life changing experience. It’s magic, and The Way provides.

There are a couple of things we were worried about before our trip that ended up as complete non-issues.

Language, for instance, was never a major barrier. The Camino is populated by people from all over the world and English is used as frequently as Spanish. It’s true that you will meet locals who don’t speak any English, and that it will be a much richer experience if you know some of the language and culture. However, it is by no means essential. Download Google Translate, and you'll figure it out.

Navigation is also straightforward. On the Frances, it is remarkable that every turn for 500 miles is clearly marked (outside of the major cities anyway). It can be helpful to have a guidebook or an app to follow, but the main way (and the main alternates) are normally entirely obvious. To help navigate the cities, I would recommend downloading an app appropriate to your route. There are a lot of options, but both Wise Pilgrim and Buen Camino are great. Both have built in navigation tools that you can use to make sure you stay on track.

I also worried - mostly based on rude internet comments - whether hikers would resent us for running. By and large, we actually had the opposite experience. The Camino community is incredibly supportive, and we had many more people cheer us on than give snarky comments (even if there were there were a few).

We managed to fit everything we needed for a summer Camino into a running pack, and carried it the entire way (more below). If you don't want to do that, or are planning to go in the colder months when you might need more gear, on the popular routes there are very affordable luggage transfer services that will shuttle your backpack between towns. With that approach you could literally bring whatever you want, and could plan a supported Camino run any time of the year.

We used a 17 liter Solomon running pack that weighed about 8 pounds, including water and food weight. (I personally carried handheld water bottles, and only once packed water on my back - on a 10 mile stretch where it turned out to be unnecessary anyway.)

For our general approach to gear, we ran in exactly the same clothes we use at home - shorts, a synthetic running shirt, and trail running shoes. We packed one change of clothes, a fleece, and toiletries. That was it. For functionality, we never bought anything extra, and we never threw anything out. It was exactly what we needed.

Clothes:

1 short sleeved tech shirt

1 pair running shorts

3 pairs of running socks

A couple pairs of underwear (REI synthetic)

Buff to use to cover dirty hair, soak in water to cool, look like a rugged adventurer

Brooks Cascadia trail running shoes

1 Patagonia Houdini wind/rain shell

1 pair of convertible long/short pants for evenings - bought at a thrift store

1 t-shirt for evenings

1 Columbia fleece sweatshirt

1 pair $2 flip flops

Gear:

Silk sleeping bag liner

Earplugs

Solomon Fastpack - 17L

20 oz water bottle x2

First aid kit

Compeed bandage for blisters and foot protection

1 bar of soap for body and clothes

Travel toothbrush and toothpaste

lightweight fleece towel

debit card, Passport, Pilgrim's Passport allowing access to hostels

camera

small flashlight

The only additional things we bought along the way were lotion for chafing, and a replacement pair of shoes when Angel's blew out unexpectedly.

Before the trip, I worried whether one change of clothes would be enough, but it was no issue. Every albergue has laundry facilities, and most people rotate between one pair of day clothes and one pair of evening clothes even if they brought more.

Most people on the Camino - runners or otherwise - opt for trailrunning shoes or similar. It is also entirely feasible to wear normal road runners if that’s what you’re used to. (I've actually done both. When we walked the Coastal Camino Portuguese, I wore Brooks Ghost road shoes.) If you’re an experienced distance runner, anything you wear on your long training days will likely work for the Camino.

My biggest gear worry was that our sleeping bag liners wouldn’t be warm enough overnight. For a summer trip, they were plenty. Blankets were available for rent in many albergues, but even on the coldest nights on our trip I wouldn’t say I was anything beyond chilly without one. Angel is typically a cold sleeper and she also didn’t have issues. I’ll talk more about weather below, but the biggest temperature issue during summer in northern Spain is heat rather than cold. For spring or fall, a lightweight down quilt or sleeping bag would work and should pack small enough to fit in a fastpacking pack.

If you’re unclear on which running pack to buy, in my experience 20 - 25L packs are large enough for a packing list like ours. Fastpacking packs are designed for running while carrying several days worth of supplies, so they're a good option. Finding a comfortable pack requires an individual process of trial and error, but iRunFar.com has a “Definitive Guide to Fastpacking” which offers great advice on what to look for. The good news is that Camino runners can carry significantly less than the average fastpacker. Most decent packs will be comfortable with the 5 - 8 pounds that you’ll need to carry. Any store that carries trail running supplies should have a selection to try on - including REI in the US and MEC in Canada. Before the trip, we went on several longer runs in our fully loaded packs to make sure that they were comfortable. I would recommend doing the same.

On the Frances, Norte, and Portuguese routes, you pass through large cities with running and outdoor stores, spaced around 3 - 7 days apart on a normal schedule. There are sporting goods stores in some smaller towns as well. If you’re from North America, and are looking to replace your shoes, your preferred brands and models might not be available. Don't worry, something will be. If you need to replace a pack, the same is true. Specialized running packs will be hard to come by outside of the major cities, but it’s likely that you could find something workable along the way.

Most models of trail running shoes will be sturdy enough to last the full distance on all of the popular routes, so most people won't have to worry about replacements.

Another anxiety for the aspiring runner is whether your body will hold up to the strains of distances that are likely beyond your normal weekly average. The only time that I’ve run more than 100 miles in a week was on the Camino, and we did those kind of miles for a month straight. It's maybe a bit risky, but it's also a decent way to test your capabilities.

Injury is a legitimate concern. It’s hard to predict whether your body will hold up, and what your particular problems might be. I can tell you that the approach we used kept us healthy beyond a minor (if frustrating) quadriceps strain in the last few days of the trip. We were in ultramarathon shape beforehand, so we went in with a high level of fitness. And we essentially never ran fast. We kept all of our running at a leisurely pace, and hiked when we were tired or sore. When we woke up it was common to feel stiff and tight, so we started out slowly, particularly on cold mornings when muscle strains are more likely. We rarely averaged more than 5 miles per hour per day, which was well below our normal pace for trail runs of equivalent distance and elevation gain. We also took about one rest day a week in order to let our bodies recover.

My advice is to have a contingency plan for injury. Many of the accounts of Camino runners I’ve read end with the individual quitting due to relatively minor problems (muscle strains or tendonitis). In my opinion, unless you're shooting for a record, it's better to be emotionally prepared to walk for extended periods. Better to complete the whole Way with a combined hike/run approach than to give up with an injury you could've kept moving through.

If you do develop injuries, basic healthcare is extensively available along the Camino. Pharmacies are almost as abundant as albergues. In Spain, pharmacists have wider prescriptive latitude than in the US, and they can typically help manage minor issues. Because the Camino is populated largely by first timers, they’re experts in foot care. Emergency services, hospitals and medical facilities are available in all major cities, and on most of the routes there are thousands of pilgrims along the way who will help if you injure yourself.

We didn’t carry travel insurance, but we probably should have. Healthcare in Spain is dramatically cheaper than in the US, but it’s still a trip ruiner to spend thousands of dollars on a hospital visit if you take a bad fall and end up with a break or serious injury.

The Camino routes spiderweb across the entire Iberian peninsula, parts of which are mountainous, and weather can vary significantly regardless of season. However, speaking broadly, weather on the Camino follows these patterns:

December/January: Usually mild compared to much of North America/Northern Europe, but high potential for below freezing temperatures even during the day. Snow makes high routes difficult and often impassable. Expect rain and precipitation, and many albergues and restaurants won’t be open.

February: Still cold, and some high sections still not passable. Expect rain and snow.

March/April/May: Shoulder season. Cool temperatures generally, high potential for just about anything: snow (especially in March), rain and occasional hot spells (especially in May).

June/July/August: Warm to searingly hot (80s – 100s F), even into nighttime hours. Generally dry and sunny, with occasional cool, rainy days in the Pyrenees and Galicia.

September/October: Shoulder season. Cooling in September to pleasant/cool in October. Wetter than summer but drier than spring.

November: High potential for cold, wet conditions and/or early freezes.

Most Camino routes can be completed any time of year, but in the colder months pilgrims need to utilize alternates and prepare for harsh weather. Most people complete their trips between the beginning of March and the beginning of November.

If you’re considering a summer Camino, be aware that mornings tend to be cool. The hottest part of the day tends to be between 2 - 4 pm., and heat lingers well into the night (particularly inside albergues).

As a runner, the heat can be challenging, but the cool morning/warm evening pattern can be advantageous. It means that you don’t need a sleeping bag, and if you start early you can get your daily mileage out of the way during the coolest part of the day. We normally left around 8 am, and rarely ran past 1 - 2 pm, with lots of stops in the middle.

The shoulder seasons (April/May, September/October) are maybe better temperatures than summer for running, but the cooler nights do require you to carry more gear. You should pack a pair of long underwear and a decent rain coat (Frogg Toggs are cheap, light and packable). These, along with a packable down quilt or light sleeping bag should still fit comfortably into a 25L fastpacking backpack. Be aware that, on the Frances, in the shoulder season the more scenic high-routes are often closed (particularly in April/May). Lower alternates are available that are passable throughout the year. (Irish adventure runner Moire O’Sullivan has a packing list for an offseason Camino run here.)

If you want to get the most out of the Camino, throw out the idea that eating and drinking will primarily be about “fueling.” The easy accessibility of real, good food is maybe the best thing about the trip.

Every cafe along the way has Coca Cola and fresh orange juice available. That, along with breads, pastries, and croissants make for good, high carb options. Ever-present bocadillos (basic sandwiches), coffee and fresh fruit are available for quick high calorie lunches with enough fat, protein and caffeine to keep you going. For dinner, cheap pilgrim menus are available at many restaurants that include meat or pasta, potatoes, salad, soup and a dessert. If you are vegetarian or vegan, there are real challenges to holding to your normal diet along the way, but it can be done. Here’s a starting resource for advice.

Spain’s a modern country, so there are plenty of options available, particularly in the bigger towns and cities. We had Basque cake, pulpo (octopus), escargot, Thai, kebab, pasta, and burgers at various points along the way.

Drinking water is plentiful and you don’t need to carry a way to filter or treat. Public fuentes (drinking fountains) are incredibly common on the Frances. On other routes, they're less so, but restaurants and bars are helpful in refilling bottles, particularly if you buy something.

The entirety of the Camino Frances is dotted with albergues (pilgrim hostels) every 3 - 10 miles where you can get a bed, a shower, and laundry at a very affordable price. They're less frequent on some of the other Caminos, but accommodations are accessible at manageable intervals on all of the routes I listed above.

There are scores of hotels and B&Bs along the way, but because I’m pro-simplicity, I’m also pro-albergue. They are easily accessible, they’re cheap, and they’re reliable. They also sometimes have on-site meals or stores, so they can make for one stop shopping.

There is huge variation in quality and style, but in general, if you’ve stayed in a youth hostel, you know what an albergue is like. You pay for a mattress in a dormitory style room. Usually sheets and pillows are included. Blankets are sometimes available, often at a small cost. There are basic cooking facilities, though often not utensils, and the range of what is available is huge – from one burner to full kitchens. Some serve group meals for purchase. There are always showers and facilities for hand-washing clothes, and often laundry machines.

Albergues can be private or public (i.e. associated with a parish church or civic organization). Public albergues are usually a couple of Euros cheaper. Word of mouth and recommendations from other hospitaleros (albergue-owners) can be the best way to make decisions about where to stay from day to day. Some are amazing, a few are dingy, but most are much more pleasant than you would expect for the cost. Hospitaleros are, in the vast majority of cases, great people who love pilgrims, and will work to make your experience the best it can be.

There are laws governing how public albergues operate, so there are a few peculiarities. Public albergues have limited check-in hours (starting in the afternoon and closing in mid-evening), and relatively early check-out requirements – 8 am, usually. Travelers are only allowed to stay one night (unless held up by an illness or injury), and there are official curfews when doors are locked – usually 10 pm. If you’re planning to be out into the evening, make sure you are aware of those hours, and if there is a way to get into the building if you arrive after them!

Private albergues have fewer restrictions, and typically operate like standard hostels.

If you're planning to ship a bag forward, unfortunately it'll be tricky to use public albergues, because they typically don't accept baggage transfers. It's easy enough to find private options in most places.

A potential downside to albergues for a runner is that they can be noisy, and large groups of people smell bad. The good news is that, if you’re doing long days and need your sleep, there are private rooms, refugios, hotels, and other generally affordable types of accommodation available. In most places, you don’t have to stay in an albergue if you don’t want to.

If you’re running, you probably aren’t carrying a tent anyway, but if you’re curious, I’m personally not pro-camping on the Camino. For most of the routes, it can be difficult to find legal places to set up a tent. Because hostel beds are so cheap and accessible, most find that their tent is unnecessary weight. If you want to sleep outdoors, or need your privacy, a bivy or light tarp would be a nice way to keep the option open, especially in summer when nights are warm.

Budget and Money

The cost of running the Camino isn't notably different from the cost of walking it.

A common figure you hear is that the Camino costs 45 - 50€/day if you stay in albergues. This is generally true as a base cost for the essentials. It's been a few years now, but my wife and I budgeted 50€/day each, took several nights off in decent hotels, ate whatever we wanted, bought a new pair of shoes, drank more alcohol than we should have, and still came in well under budget.

You could spend less than that if you shop in groceries rather than eating at bars and restaurants (which we did for almost every meal), and of course alcohol is a completely unnecessary expense (though it is hard to pass up, because Spanish wine is fantastic). Portugal is a little bit cheaper than Spain, so the routes in those countries can be even more affordable.

Budget in a bit extra for supplies (pharmaceuticals, for instance), and have an emergency fund for things like new shoes or gear if you aren’t confident in yours.

For most people outside of Europe, the cost of gear and travel to and from the Camino will be higher than the actual trip.

Although this changed somewhat with Covid, the Camino is still a cash economy in places. ATMs are widely available. Carry enough cash for 3 days of food and accommodation and hide an additional stash of 100€ somewhere on your person, and you’ll be fine.

And, as always when travelling internationally, notify your bank about your travel plans so they don’t disable your debit and/or credit card due to suspected fraud.

As a percentage of pilgrims, the population of runners is small, but there have been a number of people in recent years who’ve written about their experience running the Camino.

A runner whose story was influential in our decision to run was the Irish blogger and adventure racer Moire O’Sullivan. She traveled in the spring and carried a pack that was a bit heavier than ours, and helpfully wrote up a packing list. Her experience might be instructive for those considering going a bit less lightweight or travelling outside of the summer months.

David Power wrote up a nice account of his experience running 100 km of the Camino Portuguese.

Jenny Anderson chronicled her successful speed record attempt, which she completed in winter, and it reads as an intriguing story if also a particularly gruelling way to approach the trail.

If you are seriously considering running the Camino, have a look at my comprehensive guidebook to the Camino Frances, The Camino for the Rest of Us.

Your most valuable online starting place for planning is The Confraternity of St. James .

Based in the UK, this organization is designed specifically to help pilgrims succeed, and their website is, in my opinion, the best English language resource available online. What you’ll find here includes a guide to the history of the Camino, information about the various routes, transportation advice, information on accommodations along the way, information on off-season hiking, and more.

Marathon Handbook also has a useful article about running the Camino, with a lot of good information.

If you want to talk to someone with experience, Camino de Santiago All Routes is a supportive Facebook community.

Like the Camino community itself, this group is remarkably supportive. It’s huge, and any question you ask is likely to get a range of responses. It’s a great place to find other people planning their trips, and to ask for advice from those who’ve already done it.

I mentioned Apps above, but my favorite are Wise Pilgrim and Buen Camino

If you have specific questions, feel free to reach out to me via the contact form on my About page

April 24, 2024

Going on a pilgrimage is not a strange thing to do.

This is an excerpt from the upcoming guidebook, "The Camino for the Rest of Us," which will be available on May 6th, 2024.

Regular, modern people in the English-speaking world have a funny relationship with pilgrimage these days. For most of us, it’s familiar, but also foreign. Pilgrimage is like developing film in a dark room or weaving a sweater on a loom. We know it happens, but it’s not exactly our thing.

The idea of pilgrimage is common enough. It’s climbing the mountain to get to the sage at the top. It’s Luke Skywalker going to Dagobah to train with Yoda. It’s Frodo carrying the ring to Mordor. It’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.

You almost definitely have a vague sense of what I mean, right?

If pressed, you could probably even give a basic definition of pilgrimage, something like what Wikipedia says: pilgrimage is “a long journey towards a specific physical place, undertaken with some type of spiritual or moral purpose.”

That seems right, doesn’t it? It’s like a long trip you take to try to achieve enlightenment or something?

Pilgrimage is still a familiar cultural concept.

But also, you might not have much personal experience with pilgrimage. That wouldn’t be surprising. “Going on pilgrimage” isn’t a normal thing to do nowadays. “Long journeys undertaken with spiritual or moral purposes” aren’t a standard feature of modern life - at least for people who are likely to be reading this book.

That’s all true.

We should recognize though, that this does not mean that pilgrimage is weird.

And actually, we’re the weird ones for not understanding that pilgrimage is normal.

Outside of the secular, English-speaking world, pilgrimage is still a hugely popular reason to travel. In fact, it’s a central feature of life for billions of modern people. 10 million people travel to the Buddhist temple at Nanputuo in Xiamen, China every year. 2000 people a day make the pilgrimage to Bodh Gaya in India. All Muslims are expected to complete the Hajj to Mecca at some point in life, and a million people do so annually. For a whole lot of people, pilgrimage is a very common experience.

Even in the English-speaking world, until relatively recently, pilgrimage was very popular - the primary impetus for travel even. In her book Assassination Vacation, Sarah Vowell said “The medieval pilgrimage routes, in which Christians walked from church to church to commune with the innards of saints, are the beginnings of the modern tourism industry.”

It was one of the few good excuses to leave home and go on a long trip in the days before paid vacation time.

Pilgrimage is, and always has been, normal. It’s only our own peculiar history that’s made pilgrimage seem like an unusual experience.

You might wonder why this is. For a gross oversimplification, it’s because the same forces that weakened the Camino after the Reformation - Protestantism and politics - killed pilgrimage culture in the English-speaking world.

European pilgrimage practices grew up as part of Catholic tradition during the Middle Ages. During the Reformation, however, Protestantism replaced Catholicism as the dominant form of religion in much of Northern Europe. When it did, the Protestants attacked pilgrimage as a corrupt practice, and a means of earning God’s favor through works outside of faith. They hated that sort of thing. Broadly speaking, Protestant reformers treated pilgrimage as a religious affront, rather than a virtuous spiritual undertaking. The early Protestants could be real killjoys.

These religious attacks, alongside the political upheaval that accompanied the Reformation, dried up and cut off old pilgrimage routes through Europe from the 16th century onwards. During the same period, Protestants colonized much of the world, and pilgrimage never developed as a common practice as those colonies grew into modern nations.

In a later historical double whammy, after the World Wars, much of Europe developed into something like a post-religious society. While religious identity is a complex thing to track, and many Europeans would still identify as Christians, church attendance and active religious practice collapsed after World War II through most of Northern and Western Europe. Because the traditional impetus for pilgrimage in Europe was religious, for a time traditional European pilgrimage routes stopped making sense.

All of these factors still shape attitudes towards pilgrimage today. These days, your priest probably won’t prescribe pilgrimage as a spiritual intervention, because you probably don’t have a priest. And, you probably won’t join your billions of inter-religious neighbors on their pilgrimages for roughly the same set of reasons that you probably won’t turn up at their places of worship this weekend.

Nowadays, pilgrimage seems foreign to us because we live in a strange, small historical bubble where it’s not a common practice.

But the Camino’s resurgence - and the fact that we’re here thinking about it - is a positive sign that pilgrimage is making a comeback in our part of the world. I think it’s part of a trend, alongside the popularization of thru-hiking long trails in the United States, and the Gap Year overseas experience in the Commonwealth countries. I know I keep mentioning those travel experiences, but it’s justified. Read the book Wild by Cheryl Strayed and you’ll find the story of a pilgrimage on the Pacific Crest Trail. Read The People’s Guide to Mexico by Carl Franz and you’ll find a guidebook to pilgrimage through international wandering. Long trips to important places are moving back to the center of English-speaking culture.

It makes sense. If everyone else is doing it, why can’t we?

Regardless though, welcome back to the world of pilgrimage. You’re not weird for being here.

Whether you know it or not, by doing the Camino you’re stepping back into that rich, fragrant, international world of pilgrimage. You’re stepping alongside Buddhists circling Shikoku on the 88 Temples pilgrimage in Japan. You’re bathing in the Ganges alongside Hindu believers in India. You’re walking with thousands of modern Taoists carrying a statue of the sea goddess Mazu on a circuit through western Taiwan. You’re traveling with new-age hippies and old-school Catholics to wash in the healing waters at Lourdes, France.

Maybe that’s weird.

Or, maybe it’s awesome.

It can indeed be hard to identify with guys dressed up like Jesus, walking on their knees, dragging crosses to cathedrals on Good Friday. And what have druids got to do with me, walking from Glastonbury to Stonehenge to worship pagan gods on the solstice?

But if billions of people across time and culture have done this sort of thing, there’s got to be something to it, right?

Just the culture itself is something to see. Pilgrimage practices are colorful and diverse, and the Camino’s ancient monasteries, ornate cathedrals, crumbling ruins, unique vocabulary, and confusing religious rituals are an experience in themselves. Walking the Camino means being welcomed into a thousand years of history and tradition.

Beyond that, it’s participating in a universal experience alongside billions of our friends and neighbors, reclaiming a practice that we never should have given up in the first place.

Sign up for the mailing list on the homepage for more stories, and release news about "The Camino for the Rest of Us."

April 19, 2024

Running the Camino de Santiago, or A Poor Excuse for a Religious Pilgrim

In just a few weeks I'm releasing a new Camino de Santiago guidebook, "The Camino for the Rest of Us." This is the story of my first pilgrimage.

St. Francis of Assisi, the Buddha, and Gandhi all went on religious pilgrimage, wandering hundreds of miles on foot in search of enlightenment. Then again, so did I. You don't have to get all sanctimonious about it.

The first time I remember hearing about the Camino de Santiago, I was in the process of trying to become an Episcopal priest. Someone at my church had just gotten back. The experience sounded amazing. Exotic - a month-long walk through medieval Spain. It also sounded religious. She was religious. She did religious things along the way and gave PowerPoint presentations about the religious stuff to the religious people at church.

This was early in my adult life - my mid-twenties. My wife Angel and I were still getting our feet under ourselves. We’d just moved to a new city - Seattle. She was in grad school. I’d finished a theology degree and had joined the Episcopal Church after leaving behind my evangelical upbringing. I couldn’t find a church job so I packed bottles into boxes in a warehouse, staring out through a bay door at a skeezy meth hotel every morning, through persistent Pacific Northwest drizzle.

The church wasn’t a great fit. Actually, life wasn’t great in general. I forgot about the Camino in the blur of broken bottles and existential dread.

Seven years later, the Camino came up again when I was doing something that surely would have disappointed my childhood pastor - officiating a wedding for a couple of lesbian friends. After spending my 20’s trying to become a priest, Angel and I had left the church. I’d recently written a book announcing my loss of faith. (Histrionic, I know.) They’ll ordain you online these days though, so I could still marry my friends. (In your face, religious bureaucracy.)

When we were planning for the ceremony, our friends mentioned that they were thinking about walking the Camino after the wedding. I don’t remember who suggested it. I’d like to think we weren’t the type of people who’d invite ourselves along on another couple’s honeymoon, but who knows? At some point Angel and I decided to join.

Our friends weren’t Catholic, or Christian of any sort actually. They just liked Europe. We ate pizza and watched the Martin Sheen film The Way together. It was a bit saccharine but it made the Camino seem approachable. I read up on it. There were a few of those online types who insisted that to be a true pilgrim you had to be a Christian. That isn’t the Church’s position, and most people on the Camino these days don’t go for religious reasons. The Spanish Catholics who ran the show didn’t sound intrusive. It seemed like it would be like visiting a cathedral. You can go in and look around but you don’t have to join the faith. It seemed like the Camino would be fine.

—

We had a year to plan, and it turned into a whole thing. We were originally going to walk, tagging along with our friends like a normal person would. But when you leave the church as a minister it creates all sorts of neuroses. Running through the woods is an efficient way to cope with them, so we’d been doing that a lot. The winter before our trip, we signed up for a 100 mile ultramarathon scheduled for a month after our Camino. We were meant to be at the peak of our training during the time we’d be on trail.

We decided that we could use the Camino to get fit for the 100 if we ran it instead of walking. It was a win-win, but it would require us to become questionable friends and only spend the first few days with the couple who’d come up with the idea. In life you try to balance your priorities and regulate your emotions and pursue your goals and sometimes you come out feeling low grade shitty, or at least rude. I don’t know. I don’t know what the etiquette is for going on someone else’s honeymoon, and how much space you should give them. It seemed like they were okay with it. It doesn’t matter now, that’s what we did.

—

The Way starts in St-Jean-Pied-de-Port, a small French town hugging the border with Spain on the edge of the Pyrenees. It feels like old Europe there. A compact little town nestled along the River Nive at the base of the mountains, it’s all narrow alleys, and rows of stucco and stone houses. We didn’t see livestock in the street, but they wouldn’t have been out of place. When we arrived it was drizzling. There was smoke rising from chimneys even with summer well-underway.

We waited in line with a crowd of others to pick up our pilgrim credentials from an office that felt like a church basement, volunteers sitting behind flimsy desks under fluorescent lights. On the Camino you carry this paper folder and collect stamps along the way to prove that you’ve completed the journey when you get to Santiago. You can get them lots of places, but if you pick it up in St. Jean, the guy behind the table asks you if you’re walking with spiritual motives. I’m not sure what that means anymore, so I just said yes.

The Pilgrim office didn’t have much atmosphere, but our hostel did - a dark old albergue with rough stone walls, wooden bunks, and scratchy wool blankets. In the damp chill it felt medieval, like it should. In my memory our room was lit by candlelight, but I’m sure that isn’t right. We checked in before going out for our only French dinner of the trip, then met our friends who arrived shortly after. I couldn’t sleep because jetlag on the flight to Europe is always the worst, and because contemplating the Camino is exciting.

On trail the first morning, the international crowd didn’t feel like ascetic religious types. We headed out of St. Jean with a herd of retirees in zip-off pants and rain ponchos. A few backpackers with man buns and harem pants were scattered in. We were the only ones in short shorts and tiny running packs, but the crowd was diverse enough that it was hard to feel like you stood out.

The first day on the Camino Frances is meant to be the hardest of them all, and you go up and over Roncevaux Pass through a majestic, rolling section of the Pyrenees. We started in fog but it burned off as we ascended through the morning. When we reached the pass after a few hours it was picturesque. Blue skies, with a few remaining clouds hugging deep green hills, dotted with sheep and cattle. There’s this famous statue of the Virgin Mary on the way up, a blessing for pilgrims commencing their journey. Emilio Estevez’s character in The Way gets lost in a storm and dies nearby. That makes pilgrims nervous these days, but it was June. In summer there’s really nothing to get worked up about.

The Camino is full of these kinds of places, where you know it’s supposed to be a liminal place where magical things happen. You go in expecting that, so you experience it that way - like you’re participating in an ancient myth. At Roncevaux Pass it’s easy, because there’s so much history. Along with 1200 years worth of pilgrims, the pass featured prominently in The Song of Roland, one of Europe’s oldest pieces of literature. In the epic poem, Roland was one of Charlemagne’s bravest warriors. In a lot of local Basque legend, he’s transformed into something like an abusive ogre. Pardon my French, but there’s still a strong sense of “joan zaitez” here. If Google translate is to be trusted, that’s Basque for “fuck off.” Basque country is independent culturally if not politically.

The point is, you don’t just feel like you’re visiting Spain. You feel yourself becoming a part of the story, another soul passing through the portal into Camino legend.

—-

The first night we stayed in a giant albergue at Roncesvalles - not so much a town as a pilgrim refuge. There are 250 bunks, a chapel, and a few places to get some food. There’s been a hostel here since the 12th century. It’s the first of many places along the Camino that wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the pilgrims.

The old building was recently remodeled. There was new tan carpet. The check-in desk felt almost like a hotel, and there were dozens of people milling in the shared spaces. Angel and I sat down with our friends at this glass table. Another group of pilgrims inserted themselves into our conversation.

“Hey you guys! Are you Americans too? We’re from Florida! Why are you walking? Are you religious? We’re not religious!”

Everyone’s anxious to figure out their place in this strange new world that we’ve all just wandered into. Still, why are Americans like this?

We went to sleep that night in bunks all shoved together - 250 of us packed in to a big warehouse space. There were smelly pilgrims. Really smelly. It’s hard to understand how body odor could’ve gotten this bad in one day. You realize straight away that you’re going to have to strategize to avoid the stink and the snoring.

At a cafe on our way into Pamplona, we ordered the fresh squeezed orange juice and the cafe con leche that you can get everywhere, and sat down outside on a square. The tables were full, and this priest came up and asked to sit down. There are all sorts of pastors, monks, and ministers on the Camino. Most are fine, but you can tell that you’re in for it when they’re walking in their black shirts and collars. There’s no reason to do that in the hot sun unless you’re desperate for people to know that you’re a priest. It turns out he was an Episcopalian - from Louisiana I think, or one of those other Southern states.

I told him I’d been an Episcopalian too, but I was lapsed. It’s hard to be a lapsed Episcopalian, because they don’t hold you to much of a standard. Anyway though, I didn’t want to talk about it. Angel and I tried to steer the conversation away from religion, but the priest kept going probing us about whether we had spiritual reasons for walking.

In retrospect I don’t think he knew any other way of relating, and I’m sure he found his people quickly enough on the Camino. He just represented a lot of baggage to me. We didn’t pursue the relationship.

Instead, we discovered the clear advantage of running the Camino. We said our goodbyes, and ran away from the conversation. It was thrilling, even if just for the symbolism of it all. I was an apostate on this ostensibly religious walk, literally running away from religion.

If you think I’m being disrespectful, it also felt appropriate. They’re around, and they could be loud, but the sanctimonious priests and the keen proselytizers were the ones out of place on the Camino. We weren’t the only ones grumbling about the people insisting others listen to their spiritual opinions. People go looking for things on the Camino, but they aren’t looking to be converted or told that they’re doing it wrong. The official stance of the Catholic Church is that the Camino is meant to be a place where non-religious people are welcomed and the devout provide a witness through hospitality. But it’s not a place for spiritual pressure. The Way can speak for itself.

We said goodbye to our friends shortly after Pamplona, and pushed ahead while they enjoyed their honeymoon.

—

What do you do when you run the Camino?

If you’re like us, you try not to overdo it because you have to keep this up for a month. You stop for coffee and these delicious salty, crunchy sandwiches called bocadillos. You stop at cafes when you’re hot and you drink a Coke or some orange juice. You take pictures of landscapes and cows and little stone villages.

Running across a country sounds tough. You’d think it would be exhausting. The secret though is that it mostly wasn’t. We ran what we could and we walked what we couldn’t. It was like being a child in summer again - playing outside, doing what you want, only coming in for snacktime and sleep.

We would regularly stop in to the ancient churches that line the way. Prior to this trip, I’m not sure that I’d been in a church in three years. Maybe once or twice?

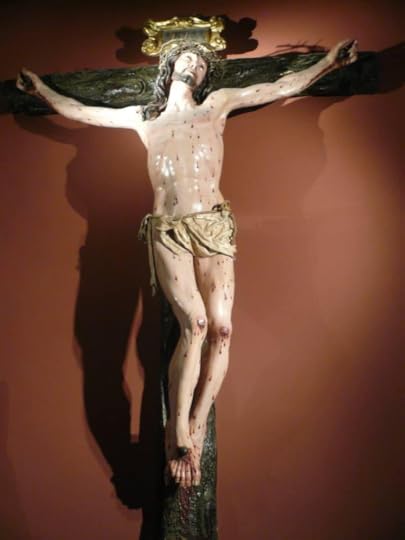

It wasn’t like home though in the States. The churches were ancient, and felt like a nice refuge. The weather warmed rapidly after the Pyrenees but the churches were cool in the heat. They were dark wood and gray stone and shiny brass. Each had its own sculpted image of Jesus crucified on the cross, in various stages of agony. Most had icons or statues or stained glass renderings of St. James. Sometimes St. James was portrayed as Matamoros - St. James the Moor Killer. He’s Spain’s patron saint, and for a time he was often presented as a warrior leading the charge against Muslim invaders. There were times when it was just us and the bloody Jesuses and the warrior St. Jameses so you’d be there in total silence. It’s a strange emotion, being alone in a big ornate room with poor tortured Jesus and raging St. James.

I’d spent 30 years being told weekly that these sorts of crucifixion images portrayed the most important event in history, and telling others the same. I believed it for most of that time, but when you leave church and stop that regular reinforcement those ideas slip away. It just feels shocking, the violence. The religious might say that this is why regular church attendance is important, so you don’t lose faith in the transformative importance of Christ’s suffering. I don’t think that says good things about the belief system. When you lose social pressure to believe, the ideas fade away and you’re just left with uneasy feelings.

I had a Masters degree in this stuff. More importantly I had felt it in my heart for years. But here it was foreign. It was Spanish and Catholic. It was also disconnected from who I was now. I was part of this but I didn’t have to feign uncritical acceptance anymore. I didn’t have to justify or apologize for it.

Anyway, on the Camino, this is the history that you enter into. It feels uncomfortable, but every story has its problems - any stream of human history you choose to identify with.

The more entertaining part of the religious culture in Spain are the festivals. San Fermin in Pamplona is the most famous (thanks Hemingway). It commemorates a saint who was martyred by being drug behind a bull. Every town has a festival though, and along the Camino you come up on bonfires and fireworks and marching bands celebrating somebody’s ancient miracles or violent death. The stories are there, but my impression is that it’s the parties that matter. Most people are only vaguely aware of the myths. That’s mostly what religion is like in Europe these days, right?

We passed through Pamplona before San Fermin so we didn’t go ourselves, but during the festival they’d broadcast updates from the running of the bulls on the televisions in the cafes. It was all scenes of terrified crowds being voluntarily trampled and gored. During basketball games on ESPN they have those little headline tickers at the bottom of the screen with running scores. Here, the tickers kept tally of how many people had been maimed that day and how.

The first time we attended a formal service, we went to this ancient little chapel with weathered plaster and faded icons on the walls. There were monks chanting. Honestly, I don’t remember where it was along the trail, or if they were even monks. Maybe it was just a men’s choir in robes? In any case, it was evening prayer so it was nothing scary. Just singing in Latin. There was no sermon and it was only 30 minutes. Catholics keep to a schedule, unlike the evangelicals and the pentecostals I was raised with. Those guys keep going until they break you down, and convince you to confess that you’re a sinner and repent. You end up in tears. Otherwise they’ll never shut up with their tongues and their shouting.

I didn’t understand anything the monks were saying. I could feel whatever I wanted then, and can remember it however I want to now. It was voices echoing off walls, blessing a room full of pilgrims as we prepared to go to sleep for the night. The timelessness of all of this. It was what had shaped me. That I could be here, and be at peace, and not feel connected to it. Or feel connected to it but not oppressed by it. Not controlled by it. This is a thousand years old, this tradition. But it’s also boring. It’s just a couple of guys who, lets be honest, are probably kind of weird, shouting in tune in an old room. But that is magic somehow. Weird guys have been doing boring chants here for a thousand years. People like me have been wondering if it actually means anything for a thousand years.

I had to wipe a few tears away, but I don’t know if it’s because I was connecting with God. It there is a God, I do think that this is what they’re like. I think you find them in those moments where you can’t fully conceptualize what’s going on, but you feel the connection to things bigger than yourself. If there is a God, they stay so hidden as to be invisible. So invisible that you wouldn’t know for sure that they exist, even if you might suspect it sometimes in moments of transcendence like when those weird guys are chanting.

Mostly, this is what God is like on the Camino. I’d been right that you could ignore the religious part. Not that you could ignore it actually, but that it wouldn’t be forced on you. You could take it at your own pace. We didn’t have to go into churches, and we didn’t have to listen to guys chanting. We could’ve run with the bulls if we wanted, but we didn’t.

Still, there is an unavoidable ritual to the Camino, which some people might think of as religious. You get up in the morning, eat, run, eat, run, walk, eat, stop, shower, eat, drink, chat, sleep. You pass through woods and towns and across fields and over dozens and dozens of stone bridges on streams and rivers. Religion and history provide you with a stream of aesthetic experiences and stories.

There are stone crosses everywhere but the only symbols you can’t tune out are the scallop shells and the bright yellow arrows. Those mark the trail and reassure you you’re on track, every few hundred meters the entire way.

The arrows aren’t spiritual symbols. They’re a pragmatic tool, which were first painted along the way by an intrepid priest in the 1980s. Nowadays they’re kept up by spirited locals.

The shells might be a pre-Christian symbol, but it’s not clear. There are these old stories about saints being raised from the sea after shipwrecks covered in scallop shells. Those stories seem like they must be syncretistic Christian myths blended with pagan legends. I don’t have any proof of that. The first documented association between scallop shells and the Camino was during the Middle Ages. During that time the shells had a few practical uses for pilgrims. You could use them for scooping drinking water. You could show them to your friends back home to prove that you’d made it to Santiago and had your sins forgiven. You could hang them around your neck to identify yourself as a pilgrim to the god-fearing bandits who’d be spooked by that sort of thing.

Now people buy them at souvenir shops and hang them on their bags the way emo kids used to hang little stuffed animals. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

After a few weeks, we attended a pilgrim mass in a grand old church. I was uncomfortable walking in. but it seemed like a part of the experience. I was an observer, or the type of participant I’d be if I were in one of those ornate Taoist temples in China, with all of the gold dragons. All pilgrims are welcome at the mass, but I didn’t go up for communion. That’s the symbol of church membership. They don’t screen you and the priest isn’t going to tell you no, but it wasn’t just about them. Staying seated during the eucharist meant something to me.

—

Along the way you pass through different regions and different climates. You’re chilly at times in the Pyrenees, but it’s vibrant, with its green hills and farms and dozens of quaint little villages. Then your skin dries out and you start to chafe as the path levels in the Meseta - Spain’s central plains. It can feel like a desert at times there with the hot sun and the sparse villages.

You spend days walking through major cities along the way in Pamplona, Burgos and Leon. You end the trail amidst farms and soggy green hills in Galicia. There are historic Celtic cultural connections there, and it feels like it, unexpectedly enough.

We ran, but we didn’t pass through these experiences any faster than if we’d been walking. We did the same stages that the walkers follow. We just spent less time moving every day because we were going at twice the pace.

This sort of running is a life hack on the Camino because you can be the last to leave the albergue, stop a lot, and still avoid moving during the heat of the day. It was cool in the morning, and by the time it got hot, we’d be drinking cheap beer and socializing at our destination.

I’d worried that running would be isolating. In fact it was a good way to meet people. You pass everyone because you’re moving faster. If you like them you can slow down and chat. You stand out so people remember you and talk about you and have a place to begin a conversation. You get to town early and post up at a bar. Beer’s cheap so you can shout friends a round for a euro after they arrive, or they can shout you one. It wasn’t intentional but running created community for us.

You meet people, and most of them aren’t religious. For Spaniards the Camino is a cultural rite of passage. For young Americans and Koreans and Argentinians, it’s a grand adventure. For Europeans it’s a cheap means of exploration. For retirees it’s a marker of a transition into a new life.

The friends we made were international. There were a couple of Hungarian guys who were on a big holiday. One had lived in Ohio for a time, working for a pet food company. The other didn’t speak any English or Spanish - only Hungarian. We walked with him for a week and never communicated verbally. (These days Google translate would change that dynamic.) There was a teacher from Michigan, out on the biggest adventure of his life and hoping to get back some of the fitness of his youth. There was a young Italian guy. He’d been a professional footballer but had sustained a career ending injury. He’d also just broken up with his girlfriend and was trying to sort out what to do now. There was this 20-year-old Austrian kid with blond hair and an infectious smile. He was walking the Camino hoping that afterwards he’d go travel the world. There was a mom from California, walking incredibly slowly and hoping to bond with her longsuffering teenage son before he went off to college. She’d take six hours longer than us to cover the same distances and always seemed to be in pain. I’ve never met a teenager with more patience than her son.

We met this woman from New York. In the Meseta, she slept in a sketchy albergue and woke up covered in bedbug bites. She had a severe reaction and developed painful nickel-sized boils on her cheeks and neck. She walked with her face covered in cloth to protect from the sun, looking like a medieval leper. It added to the atmosphere.