Tim Mathis's Blog, page 7

March 19, 2022

Leaving religion, playing outside: What's with the post-religious dirtbags sliding into my DMs?

Listen, I know this is strangely specific, but I keep running in to people who have left their religion and latched on to the outdoors and adventure in the aftermath.

My first inkling that this might be a trend was when I came across Andy Neal, the host of The Hiker Podcast, and realized that we share a similar background as former ministers turned outdoor media people. I reached out to him and he was gracious enough to have me on his show to talk about it. It was nice therapy for me, but I wasn't sure how many people would identify.

It turns out that there were a lot. I won't out anyone because I haven't sought permission, but since I released I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation, about a dozen people have contacted me to say that they can relate to the experience of leaving behind strict, exclusive religions and immersing themselves in the outdoors immediately after. You wouldn't think that there would be a lot of overlap between the audience for The Dirtbag's Guide to Life and a memoir about losing faith, but it turns out that there is.

This may be really niche, but it seems like it's worth thinking about. What's the deal? Why do people latch on to the outdoors after leaving religion? Specifically, what does the outdoors do for the post-religious pilgrim?

I've done my own research, and here are exactly four of my thoughts:

1) The Outdoors as a place where you can have agency."Losing faith" is an inadequate and unnecessarily negative expression to describe what actually happens when someone leaves behind a religion. Religious transition is often about rejecting a set of beliefs, but it is also about stepping out of a system of authority. Religions are comprehensive systems of leadership and decision making that guide you on how to live and organize your life. That can be a useful tool at some points in life, but it can also lead to a type of dependence that holds you back from becoming an emotionally healthy adult. Strict religions can make you feel like you won't be able to exist without God or the guru giving direction to your life. As a result, leaving religion can feel like falling out of your nest, but it can also be a hugely empowering process of stepping into independence and following truth wherever it leads you.

The literal wilderness is a perfect arena for establishing a sense of agency when you've stepped into a figurative wilderness out of the structure of a strict religion. Goal driven activities like outdoor sports provide a concrete and reliable way to improve your health and self-worth, and can provide a powerful sense of control during a life transition that can otherwise feel like becoming unmoored.

Personally, it was trail running that sucked me in. The stepwise process of training for longer and longer distances, and spending increasing amounts of time and energy sorting out how to run 50k, then 50 miles, then 100 miles made me feel like I could accomplish anything at a time when I was learning to live without the reassuring authority structure of religion. I dove into trail running immediately after I left the church, and it helped me to establish confidence that I would be fine on my own. I could improve my situation, become a healthier person, and accomplish things that I'd previously believed were impossible. It was a powerful antidote to the poison of losing the structure that had previously given life direction and meaning.

Hiking, paddling, world travel, and other adventure activities can provide the same path. They lend themselves to health, growth, and the sense of individual control and mastery that the post-religious are often desperate for.

2) Spending time outdoors is therapeutic.I won't take a lot of time on this one because the point is so common as to almost be cliche (and we talked about it a lot on The Hiker Podcast), but it's worth mentioning.

The process of leaving religion screws with both your head and your heart. After leaving, it can take years to figure out what you believe about the world, and how to navigate the emotions attached to leaving behind your community, your worldview, and your way of life. Going outside doesn't replace the value of talk therapy for sorting your head out, but it is emotionally therapeutic. Where losing faith can be anxiety provoking and depression inducing, going outside is consistently a good thing for your mental health. If exercise is involved it can channel anxiety into something productive and can turn negative emotions into positive ones, but even just sitting outside helps. ,Forest bathing makes you happier and at ease.

Everyone everywhere in urban modern society should spend more time outside. When you’re pushed to your brink, it becomes both more important and more obvious that the simple act of going outside makes you feel better.

3) Leaving faith screws up your community. The outdoors gives it back.Leaving religion also means losing a significant part of your community. While people tend to think of religion as a system of beliefs, it is most importantly a system of community - a means of connection with other people. For a lot of religious people, it's their primary or even only means of connection with other people. When you lose that, you lose your grounding and your sense of place in the world.

This can be disorienting, but it can also open you up to new possibilities. There’s a strong instinct to literally run away when you leave religion, to get away from the pain of the impact on your relationships to friends and family. While it's easy to view this in negative terms as avoidance, the flight instinct isn’t always unhealthy. For a lot of people, it helps them to recognize that they have the opportunity to make something different of their life. When I left evangelicalism in my early 20s, the flight instinct helped Angel and I feel comfortable with leaving the Midwestern United States and moving to New Zealand - a choice that changed the rest of our life for the better. This sort of instinct has driven many a thru-hike, Camino, bike tour of South America, and life changing round-the-world tour.

Beyond that though, the outdoors is itself a path towards connection. While it's easy to think of the outdoors and adventure like the previous paragraph implies - as an escape from other humans - that’s a thorough misrepresentation of what it actually is. The outdoors is, in large part, a community. You can’t learn to hike, camp, trail run, travel, paddle, open water swim, mountain bike, or travel internationally without consulting someone else. Once you have learned, you would be hard pressed to actually do the activity on your own. Most of us - even introverts - eventually bunch up into packs, and the shared struggle of the activity bonds you to each other in a powerful way. The outdoors has its own culture, history and saints, and it helps you locate yourself within a larger story and community.

As someone who spent the first 12 years of my career as a minister working to build up the religious community, this fact has been a lifeline. When I quit religion entirely in 2010, I started devoting my time to the people I was meeting outside. This started first with my old blog, A Little Runny, devoted to the Washington trail running crowd. Then, Angel and I started the storytelling event series and podcast Boldly Went in 2017 as a way to help connect outdoorists of all types. I wrote The Dirtbag's Guide to Life as a sort of (ahem) bible for the outdoor community because Angel and I saw that it needed one. Now, writing for the travel, outdoors and adventure communities is the core outlet for the instincts I honed across 30 years of religious life. As such, it's a key place where I feel like I give back to the world.

4) Religion primes you for an experience of transcendence that the outdoors also delivers.There is a spirituality to the outdoors that is easy to grasp for the formerly religious.

The experience of transcendence is fundamental to religion, and they all have systems for helping people feel connected to bigger things. Whether it's snake handling, rolling in the aisles, quiet contemplation, self-flagellation, or daily prayer, all are means of feeling connected to God or ultimate reality.

The feeling of connection to something bigger is a universal human experience though, and religion doesn’t have the marked cornered. It’s a reason that fundamentalist Christians demonize things like secular music, hallucinogens and yoga classes. They provide pathways to transcendence outside of religion.

For a lot of us, the outdoors provides an even more reliable pathway towards this sort of grand connection than shavasana, cannabis or Coachella. Standing on a mountain pass at the mercy of nature’s whims. The endorphins that come with the hard work of a long slog into the wind. Sleeping on a remote beach free of social encumbrances. All of these inspire a sense of transcendence. The outdoors is a place where you realize your connection to bigger, more ancient things, and as a friend said, once you’ve found it there, it’s hard to go back to seeking God in a building.

In summary, the outdoors provides exactly what the post-religious wanderer is looking for.Religion hooks people because it provides for a lot of basic human needs. When you leave religion, you lose your means of meeting those needs. That can shatter a person. A lot of people, in my experience, find the outdoors to be a place where they can find an alternative path to a meaningful, healthy life.

This isn't a comprehensive list, but the outdoors provides you with a sense of agency and independence, a means of managing you emotions, a pathway towards community, and a reliable means towards an experience of transcendence. For the post-religious, these are often exactly what we need, particularly in the immediate aftermath of losing faith.

So, for the post-religious, you might even say that the outdoors provides a path to salvation.

For a deeper dive into the process of leaving religion and/or finding salvation in the outdoors, I hope you'll check out my books .

March 8, 2022

Do you really need to pay attention to the news? In defense of selectively ignoring problems.

I spent a lot of time last week trying to write a post about Ukraine. Instead I came up with this because I realized that I don’t know anything about Ukraine and the world is in no need of another ignorant take.

There’s an attitude among Americans (among others), that the individual can and should change the world. Government ain’t going to help you. You have to do it yourself.

It’s an attitude that’s part of our success and makeup and identity. I feel it instinctively too. I want to be the change.

It’s also a reason that we feel like we need to know what’s going on in the world, wherever that is. We need to stay up to speed with news so we can be involved in changing it. We want to make a difference, and be on the right side of history. That’s not a bad thing. It’s good.

There was a time when this type of approach to life was individually sustainable. With old media, keeping up meant reading the newspaper, maybe watching the nightly news, and being involved in causes you care about in your local community.

With new media though, full, constant immersion is possible in every significant world event happening as we speak, alongside a whole lot of insignificant world events. The future will be live streamed in its entirety.

As a result, what keeping up with the news now looks like is being involved in what Mark Manson called the internet's cycle of outrage. Something bad happens. We see it or hear about it online. Influencers and pundits offer hot takes. We offer our hot takes. Some of those hot takes become accepted truth. GoFundMe’s form. Article are written. Arguments happen online and in person. We feel angry, anxious, scared, frustrated. Sometimes that energy moves up to political movements, sometimes to protest.

Until something else happens.

Then another wave hits. The cycle moves on to the next thing. Attention shifts.

This, I suspect, has always been a general human dynamic. But it used to happen slowly, across days or weeks. Now it moves at the speed of Twitter. We used to perceive that we lived in a rippling sea of history. Now we feel like we are up against the rocks in the midst of constantly crashing waves.

I’m not the first person to recognize this. It’s the world we live in now, and it has been for more than a decade. But it is a thing that I still am sorting how to cope with personally, and I’m guessing lots of other people are too.

History is no worse than it's been beforeReal talk:

An important thing to remember is that this cycle of outrage didn’t start because anything meaningful has changed in human history. History is complicated. It’s always been complicated - disease and war and famine and poverty and racism and hatred and sociopaths are nothing new. Things now aren’t notably crappier or scarier than they have been in the past. They’re better by quite a few measures, actually, although we still face apocalyptic uncertainties (just like we always have).

What’s different is the cycle of engagement and social dynamics created by technology. This has changed our perception of our place in the world dramatically. It's made it possible to engage with events personally which historically we would have had no possible means of even knowing about. I can watch Russia invading Ukraine as I write. If I lived 500 years ago, I might not even be aware that a place like Russia existed. Or I might go to my deathbed earnestly believing that it was populated by dragons and giants.

The impulse to change the world as an individual makes sense when you’re involved in small communities, or are working on only one or two big issues at a time. It made a lot of sense 500 years ago, and a decent amount even 30 years ago. But you have to ask how the value that individuals can and should change the world is serving us in the new media environment.

It's an admirable belief, but also, my conclusion is that it will eat you alive - this impulse to change the world, coupled with constant reminders that the world is out of control.

It creates the feeling that everything is immediately urgent, and that you personally need to drop other priorities to address everything all of the time. That’s not sustainable or realistic.

The cycle of outrage works, but it also will kill youI’ll admit it.

Sometimes the groundswell created by this cycle leads to meaningful change. It creates protests and actions and turns local issues into international issues in a way that can be genuinely powerful. That is one reason we have a hard time disengaging from the cycle of outrage. A lot of times it works.

But just as often the cycle of outrage prevents change and creates only frustration, when momentum that had gathered for one issue dissipates into the emotion of another. Or, just as frequently, when competing cycles of outrage crash into each other and create warring factions within communities.

And also our attention and our desire to change the world is clearly and intentionally weaponized. Because the process is manipulated intentionally by people who understand the cycle, it’s quite easy for propaganda to work its way in rather than truth. Of note: Putin used (and is using) the cycle of outrage to convince Russians that there are Nazis in power in Ukraine and Russia needs to remove them - just like they did during World War II.

It's impossible to live engaged constantly in the cycle, or to trust it. Eventually it drives individuals to despair. You can’t actually have an impact on every outrageous world event - even in your own town, let alone the world. You will end up going down paths you'll regret later. You'll burn out.

So what are you supposed to do?I don't know man, but in my opinion:

It’s important to engage with the causes that are important to you. It’s important to make a positive impact on your world however you can, and to be part of the positive winds of change.

There's also nothing wrong with staying generally aware of what's happening in the world, which is good because nowadays it would be hard not to.

But it is also entirely appropriate to be very selective about the wave you choose to ride.

As with all things in life, you have no option but to set boundaries. You’re a powerful influential person and all of that, but you’re just one person, and you only have so much time and emotional energy. It's okay to admit that you don't have the ability to tackle it all. It’s totally healthy to step out of the outrage cycle if you’re already working on something different, or if you can’t make a reasonable impact, or if the problem is actually stupid, or if you aren’t involved in any meaningful way. Not everyone can or needs to have input on every issue. If you try, it will eat you alive.

Strategies to keep your sanity instead of watching the newsWhen confronted with a wave of outrage, I think a helpful strategy is to ask yourself whether it actually matters. There’s a lot of stupid crap that’s thrown our direction constantly, because outrage is economically valuable and politically useful.

Then, if you decide that it does matter, ask yourself if your impact on this thing will be significantly affected by avoiding emotional engagement with it. I.e. can you actually make any difference on this event? Are you likely to? Do you have the bandwidth?

If not, then you are justified in letting it go.

Some people check out and walk off into the woods altogether - literally or figuratively. I can’t judge you for that. I’ve moved more down that track than I used to be because I’ve realized that anxiety will kill me otherwise. I think it’s important to do so from time to time, and leaving for a while can be a nice reminder that day to day life actually isn’t as chaotic as the news makes it seem. Take a break. You'll be stronger after.

I also think it's important to regularly consider reorienting your relationship with the world. Don’t let social media dictate the terms of your engagement. Maybe delete Twitter and subscribe to a newspaper for a healthier relationship with news? A slower drip may be better for all of us. Definitely clean up your feeds and get rid of the provocateurs. Don’t let the pundits decide what you should care about.

I don’t advocate checking out of reality entirely. The world is a mess. We do still need to work on it collectively.

But do you personally need to feel bad about every terrible situation? Or take action on every bad situation? Or even pay attention to every situation?

It’s an impossible task to "keep up with the news" in the internet age, so you might as well resign yourself to setting your boundaries appropriately.

The world has a lot that needs fixing, and a lot of life is about figuring out how to contribute. But remind yourself that history is not more of a mess than it ever has been. It just feels that way because we live our lives standing in a firehose of pain. You have a responsibility to do what you can to make the world a better place, but you really don’t have a responsibility to drown yourself in the spray.

For more tips about preventing the modern world from eating you alive, see The Dirtbag's Guide to Life.

February 27, 2022

A time capsule from a year of post-traumatic growth: How losing faith made my life better.

In 2010, I made a series of decisions that wrecked my life when I quit church abruptly, left my career, and alienated myself from most of my friends. I'll let you decide if it's legitimate to call that trauma, but my year was plagued by the type of feelings that psychologists associate with it - anxiety, panic, detachment and confusion, difficulty believing what has happened, numbness, withdrawal from community.

There's a phenomenon called post-traumatic growth, where some people who go through really difficult events figure out ways to become stronger, more resilient people in the aftermath. They develop a greater appreciation for life, build stronger relationships, see new possibilities, or come to appreciate their own strength. Here's a helpful article about it from the American Psychological Association.

Recently I found this post on "Top 10 Learnings from 2010" that I wrote reflecting on that year, and re-reading it, I realize now that it's essentially about what that process looked like for me - how I coped, relationships that pulled me through, and seeds that were planted that produced fruit later. It's a personal record of the beginnings of post-traumatic growth.

Somewhere down the line I might write a book that ties together the events between I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation and The Dirtbag's Guide to Life. There's a story there somewhere about how a person moves from the badlands of lost identify and purpose towards a new, more meaningful life. If I do, it'll chronicle the process I started writing about here, in 2010. Some of the post is explicit about what I learned (go get some exercise). Some of it hints at the reasons why it was a period of growth vs stagnation (a strong marriage relationship, a job on a psych unit that taught coping skills and perspective). Looking back, I can see in it a lot of my personal origin story, and the beginning stages of the process of integrating old, difficult experiences with a new, better reality.

Hopefully it'll be a helpful read for those of you who can relate.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yfySK7CLEEgTop 10 learnings from 2010I've been cleaning the house, listening to The National and feeling nostalgic, so it's time for another blog post. It's been too long, friends.

I love the holidays because only a cold-hearted sheep dag wouldn't. Also, I love the end of year nostalgia and optimism that they inspire: birth and hope, out with the old in with the new, encouraging one to both reflect on the things that one has learned during the previous year and consider the hopes that one holds for the year ahead. In that spirit I've been thinking about the things that I've learned this year. It's been a big year for Angel and I, and that's worth noting and numbering, in no particular order.

1. Angel and I do best in our relationship when it's Us vs. The World. Our first big project was moving to New Zealand after we got married, when we weren't the kind of people who did such things - small town, midwestern, conservative, of modest means. Success in that big project made us feel like we could take on anything. We kind of got away from it when we moved to Seattle though, and started to work on our own projects - Angel in nursing and me in church work. This year, getting in shape and now training for a marathon has brought that back. We need a big project to do together that seems unrealistic at first. My career transition into healthcare falls into that category as well. Us vs. the world.

2. One of the biggest things I've struggled with in quitting the church and changing career tracks has been a sense of inconsequentiality. In the church world, I had a place and a feeling of importance and social standing, and I felt like I was headed towards more of that. Being a small time minister is kind of like being a celebrity to a very small number of people - most people don't care about you, but 6 - 7 people think you're awesome. Switching out of that, I have a feeling of having to remake a name for myself, and I'm not really in a field anymore that lends itself to a sense of celebrity.

3. Along similar lines, in transitioning out of ministry I've realized that even though I've often ended up in leadership positions, I don't really like the stress and expectations that come along with being the dude in charge. I think I do best when I feel like an expert and a leader, but maybe not the expert and the leader. It burns me out. I can't handle more than one such position at a time (and I currently still have two left over that I'm going to have to sort out going into the new year).

4. Along similar similar lines, when I spend most of my time studying and doing housework, as I've done during the last six months or so, I get frustrated because I don't feel like I'm doing anything consequential. I don't care about power or being in charge, but I want to do things that people care about, and I want to feel like I'm leaving something positive and concrete behind. I need to free up some time to nurture that by clearing out some of the things that drain me in life.

5. Life's better when you commit to an exercise routine, eat well, and keep yourself in shape. You feel better about yourself, you have more energy to get things done, people say nice things to you, you sleep better, your mental health issues are better regulated, you can post annoying things about how far you ran on Facebook, you don't get winded going up stairs, and you're more confident. Plus when you're in shape you want to maintain it and push yourself rather than letting yourself drift into a puddle of fat, booze and lethargy. Exercise starts to feel good after about a month, rather than feeling like a drag and a chore. It's well worth it.

6. I love/believe in/am continuously interested by religion, but it doesn't work for me unless it's tied to my worldview, culture, and identity. Evangelicalism was my first love. When my worldview evolved and changed and I became an Anglican in New Zealand, it worked because I had a sense that my beliefs lined up with the church's, and I had a sense that NZ Anglicans were people that I could be family with. When I moved back to the US, the Episcopal Church worked from a worldview perspective - probably even more than the NZ Church. But somehow the culture of the place never clicked, and as a whole I didn't feel like Episcopalians were my people somehow. Now, 6 months removed from church attendance, I don't know that I'll find an organized religious expression that works. Still, I feel like religion is a quite human thing, and is something I personally am wired for.

7. Along those lines, you really should read "The Faith Instinct" by Nicholas Wade. He talks about religion as a biological and natural phenomenon, but not in a dismissive way like those other jerk scientists like Dawkins - he's religion-positive, really. Personally, any future hope I have for religion lies in this kind of approach - scientific ideas affirming the value of structured music and community and ritual and faith. It seems like it should be possible to build on what's good in religion and start to get rid of the less helpful and truthful and beautiful aspects. I don't really want to be the one to try to sort out all of the details on that one.

8. Everyone's a little bit crazy. Working in mental health, I grow more and more convinced that we've all got at least a little bit of the propensity towards crazy. Whether it's nature or nurture that makes it come out in some more than others, I'm not sure. My kind of crazy, I think, is a mild propensity towards depression that stress brings out, and that exercise and relationships really seem to help with. Also, Ron Artest may jump into the crowd and punch fans every once in awhile, but he is also awesome and quite the unlikely hero for being open about his own struggles with mental illness and efforts to raise awareness. One of my new favorite athletes this year.

9. My Top 10 list only has 8 things on it.

February 26, 2022

I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation: A free preview

This is the introduction to my memoir about figuring out why and how to leave my faith. If you like it, buy the book .

The last time I quit a religion my decision was triggered by a room full of angry priests. The first time, I’m embarrassed to admit, it was because of internet pornography.

The turning point in that particular apostasy began in 2002 when I was a Biblical Studies major at a deeply conservative Christian university in central Kentucky called Asbury College. One day, near the end of my senior year, I was called into the office of the Dean of Men because I’d hit too many internet sites blocked by Websense. Websense, for non-Christian college graduates, was a computer program intended to prevent access to internet sites that display pictures of women’s bosoms and other sordid parts. At my college, when the Dean of Men was alerted that a young male had hit a high number of Websenses during the month, he would take a closer look at what exactly you were trying to view. If the evidence was sufficiently compelling that you were a dirty bird, he would place an index-card-sized yellow sheet in your mailbox instructing you to set an appointment to see him.

Students picked up their yellow sheets from the campus post office, which was located in a nondescript but heavily trafficked hallway in a building full of classrooms and offices. In those days, checking mail was a daily social event because it was where professors would return graded assignments and families would send wholesome care packages full of home-baked cookies and new leather Bibles. This meant that people who received the yellow Websense notifications usually did so during a busy social hour between classes, while they were courting a potential marriage partner or reviewing a term paper about Christian sexual morality with a passing professor. The documents were of course anonymous, so no one would be able to identify what they meant unless they too were a pervert, or had talked to one, or hadn’t been born yesterday. The day that I discovered one in my own mailbox, I quietly stuffed it into my pocket hoping that no one had witnessed my shame and hurried back to my apartment on the other side of campus. When I divulged to my roommates what had happened, I found out that the Dean of Men had been on the prowl that week, because two of my friends had also been flagged. It was one month before I was set to graduate from college with a Bible degree (magna cum laude) and marry the girl who I’d been dating for the previous four years and still had not slept with.

Ironically, I hit the bulk of that month’s Websenses when I was shopping online for lingerie for my fiancé, Angel, for our honeymoon. Prior to this I’d probably never hit a Websense while doing something that the administration would label as wholesome and chaste.

After I got the sheet, I had to set up an appointment with the Dean of Men by calling his grey-haired, middle-aged, Southern-belle assistant. I then had to go to his office and tell this nice lady that I was there to see him, detecting from her lack of eye contact that she knew exactly what I’d been up to. Then I had to slink uncomfortably into his office – standard administrative fare, grey carpet, small window, central-air hum, metal and fake wood desk fronted by two Office Depot chairs, upholstered in burgundy polyester.

As I sat, the Dean was merciful and spared me any small talk, holding up a printed list of the flagged sites that I had hit during the month. ‘You know why we’re here. Do we need to go over what you’ve been looking at?’

No. Of course not. Eyeing the pictures of his wife and children that were placed prominently on his desk (matching polos and khakis all around), I couldn’t help but cave under the shame and confess that I thought I had an addiction to the damned pornography (which wasn’t true). He asked me to meet with a counselor (who told me that I definitely didn’t have an actual addiction) and disconnect the internet in my dorm room for the duration of my college career (I didn’t get a rebate on the money I paid for internet access, by the way). Symbolically, he had me hand over my internet cord to him and wear a scarlet ‘A’ on my lapel (I made that last part up).

As luck would have it, my unexpected meeting with the Dean of Men made me late to a date with my future wife, and being completely unable to lie convincingly I had to tearfully explain the situation to her. It’s only weird if you make it weird. I made it super weird, and discussing my pornography viewing habits completely ruined the evening.

(Nowadays she wants you to know that she thinks this is all hilarious, by the way.)

This whole experience was of course deeply humiliating for a young evangelical like myself who was under the mistaken impression that most 22 year old Christian men have firm control over their sexual urges. It would be possible to assume that a year later, when I found myself stepping away from the evangelicalism of my youth, it was because I didn’t want to have to confront my shame. Looking back now though, I think it’s actually more likely that the experience finally helped me to realize that you should never sign up for a religion which pays people to regulate the internet viewing habits of college boys. It’s creepy and if nothing else, an obvious sign that they’ll spend your tithe money on lost causes.

I’ll eventually get to the story about leaving religion for the second time, but I want to start by letting you know that quitting church wasn’t the topic at all when I started writing this book. This was supposed to be a story about how I began life as an evangelical Christian and ended up as a hip, innovative liberal, and it was supposed to conclude with me being ordained as an Episcopal priest. Honestly, I started writing this because I harbored fantasies about positioning myself as a leading voice in the conversation about what it means to be a post-evangelical Christian in the 21st century. There’s a lot of money in that these days, and the publishers seem to be excited to print that kind of work. I thought it would resonate. By the time I finished the book, it was quite clear that things weren’t panning out that way. I hope that you find what I’m about to share to be an acceptable alternative.

In fact, I did most of the writing while I was working for the Church in a variety of capacities, and I didn’t change much of the narrative after I decided that the story would end in my departure from the Christian faith. This book hasn’t become an argument against religion, exactly. I’ll talk about the incorrect things that religion insists that you believe, and about the way that involvement with religious institutions can screw you up, but it really isn’t my goal here to complain about how bad religion is. I wrote throughout as a reasonably educated person committed to science and common sense, and it’s not exactly that I spent my life as a brainwashed fundamentalist and suddenly came to realize how horrible it all was (although something like that process is a part of my story). I don’t even really know whether to define what I’ve done as apostasy, because the spiritual line between what I was as a practicing Christian, employed as a minister in God’s church, and what I am now as an a-religious agnostic is so thin.

But this is a story about quitting church after moving through a variety of versions of Christian faith, after spending thousands of dollars on religious education, after travelling the world on pilgrimage and after allowing Christianity to define my identity for 30 years. So, even if this isn’t an argument for leaving religion behind, it is an explanation of why I have. I didn’t set out to present a story about losing faith, but that’s how it ended up.

February 25, 2022

What is a Dirtbag? An excerpt from "The Dirtbag's Guide to Life"

This is an excerpt from the introduction to The Dirtbag's Guide to Life . Other people have defined the term - I'm not the first - but I wrote the book on it so I'm staking my claim. Here's how I define a sub-culture that I've learned so much from.

Who cares about the humble dirtbag?Once upon a time, in the 1950s and ‘60s, when countercultures were being born and postwar society was trying to get its act together, a group of young climbers set up camp in the Yosemite Valley. Out of some combination of social rebellion and love of the game, they chose to eschew jobs and traditional lifestyles in favor of scavenged food and a daily life of rock climbing and camping in the Valley for months or years at a time. They allegedly survived on cat food and thievery, and at some point, someone referred to them as a bunch of dirtbags, and the term stuck.

In all likelihood, “dirtbag” was originally intended as an insult, but as is sometimes the case with these things, the climbers, and those who followed them, took it up as a point of pride. They embraced their filthy tents and smelly-ass clothes as signs of commitment to the cause - signs that they were people willing to sacrifice for their passions, and to pursue them even as society rejected them for it.

As far as I know, there has never been a history written about the process of how the word “dirtbag” (both as a term and a lifestyle) has spread, but across the last 60 odd years, it has. And today, a quick Google search confirms that there are groups dispersed across the entire spectrum of outdoor activities that refer to themselves as dirtbags, all living a similar life of sacrificial devotion to the cause: trail runners, hikers, paddlers, skiers, climbers, world-travelers, mountain bikers, and more. Regarded as one of the best and most well-known outdoor-related podcasts of the current time, The Dirtbag Diaries has helped to popularize this term with its 9 million plus listeners. And a recent film backed by legendary outdoor clothing and gear company Patagonia that profiles the pioneering alpinist Fred Beckey was simply titled, “Dirtbag.”

The progression happened gradually, but somewhere along the way it became possible to identify dirtbags as more than just a couple of weirdos doing weirdo shit, escalating into a full-fledged counter culture embraced by thousands. In an ,article from her blog in 2014, ultrarunner, race director and social media influencer Candice Burt identified dirtbaggery as “a growing social movement,” and she was right. The books and film adaptations of Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild made cult heroes out of people living dirtbag lifestyles, and a popular documentary called Valley Uprising was made about those original Yosemite climbers. While there’s no central organizing committee, along with those popular artistic touchstones, dirtbag culture has developed its own identifiable dress code (flannels, trucker caps, cutoffs, body hair) and sacred places (Yosemite, Squamish, Patagonia, Chamonix…), and is present in beautiful outdoor locations all over the world.

Yvon Chouinard, founder of the Patagonia brand, and quite possibly the world’s most influential dirtbag, states in his autobiography, “If you want to understand the entrepreneur, study the juvenile delinquent. The delinquent is saying with his actions, ‘This sucks, I’m going to do my own thing.’”

Chouinard might not have been talking about dirtbags specifically, but he could have been, and “This sucks, I’m going to do my own thing” summarizes the spirit of dirtbag culture as purely as anything. While the movement still might be difficult to define, there are a lot of us out there trying to figure out how to do our own thing in a world that sucks for a whole variety of reasons.

What does the dirtbag life entail?I don’t remember exactly when the concept of “dirtbagging” entered my own consciousness, but my most memorable initial encounter with the lifestyle was in getting to know Heather “Anish” Anderson, beginning at a presentation I attended where she described her experience setting a speed record during her 2014 thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail.

Heather was living in Washington State at the time, not far from Seattle, where my wife Angel and I had been living since 2005. We were all active members of the state’s trail running community, and across time, as Angel and I got to know her, Heather’s life came to exemplify, for me, what it means to live like a dirtbag.

As an athlete, Heather is a remarkable person. Like myself, she grew up as a bit of a bookish nerd in the Midwest, but she fell in love with hiking during college. Following graduation, she decided that instead of starting a career, she would thru-hike the Appalachian Trail. On that trail she adopted the trail name “Anish” - a reference to her Anishinabe heritage - and changed her entire life path. Across the last decade, she has shaped herself into one of the most notable athletes on the planet, breaking speed records on multiple American long trails that are still currently untouched by either gender.

But as a person, beyond the superhuman accomplishments, she’s a total dirtbag. In order to pursue her goals, she strayed from pursuing a more traditional post-collegiate career track, choosing instead to fund summer-long hikes on the long trails through seasonal work. Heather’s strategy seemed to pay off, earning her the coveted Triple Crown of long distance hiking: completing thru-hikes of the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Continental Divide Trail. She married another hiker and tried to settle down in Bellingham, Washington to work a straight tech job, but after just a few years, she left both her job and her marriage and dove full-on into hiking and peakbagging - setting multiple speed records across several years, and living as a full-time vagabond on occasional work and small sponsorships. At time of writing, she recently became the first woman to complete a “Calendar Year Triple Crown,” spending 9 months averaging 25 miles a day to complete the more than 7000 miles of trail on the Pacific Crest Trail, Appalachian Trail, and Continental Divide Trails in a single season. That also made her the first woman to earn a “Triple Triple Crown” - completing all three long trails three times each.

If the Yosemite climbers set out the dirtbag ideal of sacrificing a normal life for the cause, Heather epitomizes it. She’s placed exploration at the center of her existence, and sacrificed career, relationships, and financial stability to pursue her passions outside. And she’s treated hiking, running and peakbagging as spiritual callings - not just recreational pastimes. Her whole life is defined by the pursuit of exploration and adventure, and she does it all on the cheap.

Dirtbags are everywhereEncountering Heather’s story was the first time I recognized dirtbaggery as a life strategy, but once you identify this pattern of behavior - of heeding the call of the wild, and abandoning social norms in order to immerse yourself as fully as you can in a life of exploration - you start to notice it everywhere. It manifests in different ways, but the dirtbag spirit pops-up again and again.

It’s true that there are the obvious dirtbags who fit the patterns already described. In my experience within the trail running world in Washington State, I think about race directors like James Varner from Rainshadow Running and Candice Burt of Destination Trail, who got into it, in part, so they could run trail all the time and avoid working regular jobs.

But it also pops-up as a pattern among the more settled. In Tacoma, WA we know a guy named Dean Burke who’s a consummate professional in his career, but spends most mornings stand-up paddleboarding on Puget Sound, encountering orcas before work, and photographing sea life that most gritty urbanite Tacomans don’t even realize exists.

And as much as “Dirtbag” culture gets characterized as a white thing, when you travel you recognize that the same spirit is present across cultures.

In Jalcomulco, Mexico, we encountered locals who‘d lived their whole lives in that small canyon town in central Veracruz, but who were managing to eke out a living as rafting or mountain biking guides, and who spent their recreational time doing the same for fun.

And in Bolivia, we encountered the phenomenon of ,alpinist Cholitas - traditional women, indigenous descendants of the Incas, who spend their time climbing 20,000 foot peaks in traditional garb, against social custom and popular expectation.

The dirtbag spirit manifests in different ways in different contexts, but it’s a living, breathing thing.

Why are you here?This, I suppose, brings us to the current situation, meeting here on the pages of a book about dirtbagging - me having taken the time and energy to write such a thing, and you taking the time and energy to read it.

While I can’t be entirely sure what brought you here (although, let’s be honest, I’m self publishing, so Hi Mom! Thanks for reading!), it’s clear that some combination of factors is drawing a broad variety of people to a similar lifestyle - sacrificing the comforts of a normal life in order to play outside and explore the world.

The story that I tell myself is that some of you are here because you’ve gotten addicted to the feeling of “adventure” - the experience of putting yourself into situations that you aren’t sure how you’re going to get out of - and the personal growth that comes along with it.

And some of you are here because of the love of the game - you just really love being outside, or running, or climbing, or swimming in mountain lakes - and it feels more like a calling than a recreational pastime.

And some of you feel like life has pushed you in this direction. At some point, you developed a deep sense that something in normal life wasn’t working, and that the fix was somewhere out there among the rocks and dirt and streams and oceans. You’re looking for freedom, or an alternative to the pursuit of material things, or a life that is more deeply human than the one offered in the city or the suburbs.

Some of you ended up here through a long period of planning and intentional choices. Some of you maybe landed here by accident. Whatever the case, here we are, a group of dirtbags, trying to figure out what the hell we’re doing with our lives.

February 23, 2022

Big Butter Christ Crucified: Is it okay to laugh at someone’s sincerely held beliefs?

In my hometown in Southern Ohio there was a prominent prosperity gospel congregation. It was classic predatory televangelist fare: spray-tanned pastors soliciting money from a primarily working class community by promising wealth and blessings from God, and then using that wealth and blessings to buy themselves fancy cars and horse farms.

They did one thing to set themselves apart with all of that money, and commissioned Southern Ohio’s largest Jesus statue, constructed on the front lawn of the church. It was a six story Christ, frozen in a touchdown pose, facing across the highway at a local porn shop and strip club so patrons would know that Jesus was watching.

It was made of styrofoam with a thin fiberglass skin, which probably was the economical choice, but not a good aesthetic one. It gave the statue a yellowish tint, so people took to calling it Big Butter Jesus.

This is a true story.

One night, tragically, it got hit by lightning and burst into flames. In just a few hours it burned to the ground leaving behind just a metal frame. It was left looking like post-apocalyptic Terminator Jesus in the end.

The burning made national news because this is an objectively funny story. Gaudy, styrofoam Jesus destroyed by lightning, the quintessential act of God.

But also, if you’ve had a religious history, don’t you feel kind of bad laughing about it?

Even if it was made of plastic, you know that the statue was paid for by donations from a whole crowd of people who believed that they were giving to God. I can testify to the truth of that because I went to that church occasionally when I was a teenager. I’m sure I put money in their offering plate more than once because I consistently did when I went to church. I gave a 10% tithe for years because that’s what I thought God wanted. Probably some of my own money helped pay for that flaming, styrofoam Jesus.

It cost a quarter of a million dollars to build. It caused three quarters of a million in damage when it burned. That’s a lot of poor people’s money.

It was an easy target for jokes, but to the congregation Big Butter Jesus was no joke. The people who built it were expressing sincere spiritual motivations. It probably meant a lot to people in that church, and I’m sure tears were shed watching it melt into the ground.

So, is it okay to laugh about this sort of thing? Is it different from laughing while Notre Dame burned? Was that okay to laugh at?

The beliefs that drove the donations - even if sincere - were clearly wrong. If there’s a God, seriously, there’s no way they want rich grifters spending poor peoples’ money on giant styrofoam statues of themselves.

But that’s true of so many things in religion. If there’s a God, there’s no way they’re actually like what any religion says about them. Every historical religion has objectively untrue, conflicting beliefs. It’s human nature to latch on to ideas that are untrue for complex reasons. Religions all have beliefs and practices that are very easy to make fun of. Where’s the line?

Can you laugh when the Ark is damaged in a flood?A few years later, and just down the road from Big Butter Jesus in Grant County, Kentucky, fundamentalists built a gigantic scale model of Noah’s Ark according to the dimensions described in the Biblical book of Genesis. It cost a reported $100 million dollars of donated money and was cast with the grand vision of lending credence to a literal interpretation of scripture. As with the styrofoam Christ, I’m sure that some small amount of my own money went to building it because Angel and I gave regularly to a church in Louisville that supported Answers in Genesis, the organization that paid for it. (For a time in my youth I was enthusiastic about the cause, because I thought evolution was a lie from the devil.)

Shortly after it opened, the property experienced damage due to rain during a weather event that was significantly shorter than 40 days and 40 nights. The organization entered a protracted legal battle with the insurers who declined to cover the cost.

Once again, that’s an objectively funny story. Noah’s Ark, built with grandiose ideas about asserting fundamentalist superiority, damaged by a little bit of rain. Your Ark can’t stand up to the smallest act of God, so you sue the insurance company to pay for it.

Is it okay to laugh about this one? Once again, this is built on the backs of thousands of people’s sincere religious beliefs. But it’s also a structure paid for by a well-funded organization that is dedicated to the spread of false ideas. They’re spending a lot of money to do active damage to the cause of human progress. Surely it’s okay to laugh, right?

I don’t want to tell you how to answer to that question, but personally, as someone who played some small role in the construction of those golden calves, I retain the right to laugh when they burn. It just seems fair.

I don’t think that you should go out of your way to mock someone’s sincerely held beliefs. Religious beliefs are almost always more sophisticated than any public caricature might indicate, even if they seem as silly as a styrofoam Jesus or a roadside oddity Ark. All beliefs have a purpose for the believer, and they might feel like they’re relying on them to survive.

But for people who’ve been scammed or misled, I think the right to laugh at your deceiver is fundamental. For the person who’s been damaged by religion, laughter is one way to stop being victimized - to stop religion from being the source of negative emotion, and allow it to become a source of humor. It’s a way to assert your own autonomy over it. You don’t laugh at a charging gorilla in the wild, but you might if it were behind glass in the zoo. You don’t laugh at styrofoam Jesus if you still think that Pastor’s got a message from God, but you do when you decide to stop giving him money because you know that he’s full of it.

I can’t speak for everyone, but as someone who was misled by false beliefs and the institutions that propagated them, and who sincerely maintained them myself, I retain the right to laugh because otherwise I’ll just get angry. Laughing makes it feel like the power behind the ideas is in the proper place - the ideas don’t hold any sway over me anymore. If you're in the same boat, I personally won't judge you if humor helps you cope.

Is it okay to laugh at someone’s sincerely held religious beliefs? I don’t know, but I do know that it’s okay to laugh at things that have harmed you. If there’s a God, there’s no reason to mock them, but it’s a very different thing to say burn, styrofoam Jesus, burn.

I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation is my attempt to provide some catharsis for people who've left behind religious systems that left them feeling scammed or misled. It's full of this kind of ridiculousness.

February 22, 2022

Stating your intentions is the first step: Birthing Travel, the PCT, and the dream life

This is a post about taking the first step towards doing the things you dream about.

First off though, I want to say that the kids these days have it tough, because they’ll never experience a world where their entire lives aren’t chronicled online. Those embarrassing photos will always be available for the world to see.

I don't know why we do it, but it seems like it’s a natural human impulse to humiliate ourselves on the web. My childhood is mostly private because I grew up pre-internet, but I started posting regrettable things as soon as it became an option. The other day, in fact, I found my first contribution to the internet, and you’ll want to check it out. ,It’s a David Lynchian Angelfire site I built when I was 19.

Despite the pitfalls, posting embarrassing things is healthy sometimes. While I don’t know that I gain a lot from no longer knowing how to delete that old Angelfire account, when I was scrolling posts to transfer to this blog, I was reminded that my life has been dramatically changed at various points by sharing stuff online.

In particular, I came across a post from 2015 that I recognize now as a pivotal moment in my journey. It was something I wrote as a way of calling my shot - of declaring my intentions and speaking reality into being at a time when I didn't know if Angel and I could actually pull off our big, audacious goals. I wrote it shortly after telling my work I was leaving and going to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. Here’s what it said:

Prophecy 2015Angel and I are just back from an International Dream Vacation, skiing the Canadian Rockies with some Kiwi friends, enjoying unseasonably warm weather in Banff, and trying out the related unseasonably bad skiing and smelly hostels in Fernie. It was our first time downhill skiing since we were teenagers. It was fun and nothing's broken, but that's mostly neither here nor there.

Travel is always a nice chance to take a break from normal life rhythms, but for us it has also frequently been a chance to plot major life changes. Travel to Australia led to us living in New Zealand, which preceded our move to Seattle. Traveling the Camino in Spain ultimately led to a decision to hike the PCT and then go learn Spanish.

Going places makes us want to go other places.

This Canadian trip (with good Kiwi friends who we never would've met if we hadn't traveled to New Zealand) was a nice reminder that Angel and I would rather travel than do just about anything else. Hanging out with Kiwis always has that effect because they travel as well as any nationality I know and because our two years in NZ were some of the best of our life. And it was also a nice tune-up for our upcoming period of vagabonding.

Beyond just wanting to be on vacation all of the time, traveling in 2015 (and maybe beyond), is about trying to figure out how to prioritize the things that are important to us. Different people want different things in life. Some people want to spend time with their family, or make a lot of money, or have a meaningful career. All of that is important to us to some degree, but we also want to do it in the context of experiencing as much of the world as possible. Our priorities in some random order include: meaningful and beneficial work, outdoor adventures, close relationships, a sense of home, seeing as much as we can, learning as much as we can. We've spent a decade hammering away at debt, investing, buying and remodeling a home, changing careers, and trying to put ourselves in a position of professional and financial flexibility. What that adds up to at this point is a chance to try to move the balance away from career a little bit and more towards life.

A more accurate way to say it might be that we want to shift more towards a model where, when we are working, we are working intentionally - shaping our work life so that it will allow us to do more of the things that we want to do. Part of me always feels like I need to justify our decisions to travel, both to myself and others, as if they were inherently selfish. But in practice I doubt that our contributions to society will be significantly diminished by the fact that we'll be moving from place to place for some period of time in the near future. And we're lucky to be in a position where our jobs themselves are a meaningful part of the lives we'll live. If we pick up nursing work while we're traveling, it should contribute to the experience rather than feeling like a necessary evil.

The two year plan is to make this a sort of intensive Masters program in resilience and creativity: stretching the resources we have as far as they'll go, investigating what nursing can do for us to both enrich our experience and extend it, developing other skills to make money to keep traveling, sorting out how to balance being home with being away.

The long term goal is to develop a life where travel and adventure is a regular, viable possibility: More Caminos. More through hiking. Spending more time with the people and places we love. Floating the Mississippi. Going to new parts of the world. More friends. Ultras, Skiing, Biking, Mountains, Surfing.

In two months, we'll see how this goes.

What the value of a public announcement?In retrospect, this post reads as audacious and maybe a little bit self-indulgent. But while it reads like a brag to me today, at the time it genuinely didn’t feel like that. It felt like a risky public commitment to a major life change that terrified me. It was an attempt to fake it until I made it - to pretend I had the confidence to do the things Angel and I had dreamed about for years, in the hopes that the confidence would come when we tried it.

It did.

A few years later, we’ve done most of what we planned, and a lot more.

So now I can see that saying it out loud is an important part of the process in any big life decision. It’s embarrassing to talk about your visions and dreams in public, but it also helps you put together the life you want..

When you say it out loud, you’ve committed. You’ve added ego and the potential for public failure to the quest to live your dreams. You’ve also counteracted the insecure gut feeling that you’re not the type of person who does these sorts of things. You’ve put out a call to supportive friends to help you get there. And you’ve admitted to yourself that this is something that’s worth taking risks to accomplish.

So, even if I think some of my earlier posts read as self-indulgent, I can give my younger self a pass. Sharing your dreams out loud isn’t a brag. It’s an important part of the process.

So build that Angelfire site. Write that blog post. Say the things you dream about out loud. That’s not the whole battle, but it’s a first step.

My books were also initially so painful to announce publicly. Now, I think of them as the coolest things I've released into the world since that Angelfire site.

February 19, 2022

I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation and how I feel about that.

At the end of 2021, a moment that very few people had been consciously waiting for arrived.

That was the moment when I released my second book: I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation, which was actually an old book, significantly revised.

The book is the culmination of at least five years of hard work, starting when I was in my late 20s. It went through multiple iterations, and occupied almost all of my writing energy in 2021. It is also a total departure from my other book, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life. My feelings about the book have always been thoroughly mixed because it's a memoir about a period of life that was even more unpleasant than junior high school.

More than a decade prior to releasing the book in its latest version, I made the most dramatic decision of my life when I abruptly left the Christian faith after years of centering my existence on religion, while enmeshed in the process of becoming an Episcopal priest. It thoroughly screwed up my life and pissed off my family and friends, but across the long term it also allowed me to remake my life in a much healthier mould.

If you've never been a religious person, it might be hard to picture what leaving behind faith actually means. Religion isn't just a belief system or church on Sundays - especially for someone like me, who spent years studying theology and working in ministry. Faith provided my daily structure, my worldview, my sense of right and wrong, my career path and my means of making an income, and church was the place where I maintained almost all of my social relationships. Leaving all of that behind wasn't simple.

Most people who leave faith extract themselves slowly and drift out quietly, but my situation was complicated. It felt like religion was actively ruining my life, so I decided to tear it all down with one act. I decided to turn the religious memoir I'd been writing into a book about why I was leaving, and released it into the world - initially for free on a blog and then through self-publishing - as a public announcement. I wanted to be fair to the religious community, but I also wanted it to be definitive. I'd made the decision to burn bridges and get on with the process of building a new life, and I did.

I called the book I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation. I'm proud of that title, and I hoped some people would be able to relate to my experiences, but my goal wasn't to create a best seller. I invited my friends and family to read it, but I didn't do much promotion beyond that because it was excruciating to talk about the process that I was going through, and I didn't want to have more conversations about leaving religion than I needed to. It did gain some local readership and sold a few hundred copies via word of mouth and a few bursts of Facebook posting, but it wasn't really a polished product when I released it. After about a year of allowing the book to trickle through my social circle and facilitate an early midlife crisis, I let it recede into the dark corners of the internet. Every so often someone stumbled across it, but it was a rare occurrence. To the day of its re-release, I rarely even told friends that I wrote the book, because talking about it brought up too much baggage.

But during 2021 I decided to revisit the project. I took down the original book, and released an extensively revised version in its place.

The final story includes a lot of the original text in order to stay true to the emotions that I was feeling while I was making the decision to leave. It tells the same story about how I was converted as a teenager, how I tried to make myself into an evangelical minister but realized that it was a terrible fit, how I recreated myself as a progressive Christian during grad school in New Zealand, and then how my experiences of working in the Church eventually ate my soul and made me finally realize that I needed to cut ties with religious faith. It was a very personal story. The original version was largely written as therapy, to process my decision, and to have a place where I could be honest when for most of my life I had felt like I needed to put on airs. In the new version, I retooled my story with the goal of making it useful.

I'd felt for years that I should revisit the project. Religion in America has always had its issues, but after the great Trumpian shift of 2015, the disconnect between truth, goodness, and most American religion grew acutely obvious. The issues that drove me out of the church intensified, and a lot of people started going through a process of disillusionment and departure similar to my own. I suspected that there was something in my story that would be useful for these types of people, because a lot of readers of the original book told me that they found the memoir cathartic. So, in the midst of the chaos of 2020, I finally decided to go back to the project. I spent 2021 rewriting it with the goal of telling a story about why people become religious, why religion can make life better in some situations, why it also causes so many problems, and why it's so difficult to leave. The new version is not aimed at arguing that people need to leave behind their faith, but I did want to reassure people who are leaving that they are making a healthy and reasonable decision.

I have moved on from a lot of the issues that I was dealing with when I put out the original version, but I will always carry plenty of baggage around my religious history. Some days this project felt like editing an old, humiliating journal for general readership. But I spent a year reworking it, I got some dirtbag editorial input from a few really brilliant beta readers, and I smoothed out a lot of the rough edges. It still has some of the quirks you'd expect from an independently published book written by a guy in his late 20s in the midst of a spiritual crisis, but I am happy about where it is. I think it stands up next to my other book, The Dirtbag's Guide to Life, and I feel happy about the way I've presented my story. For people trying to understand either their own experiences, or the reasons that people get sucked in to religion, I think there's a lot there that's funny and honest and useful.

I still hope I was wrong about eternal damnation, but I also hope you'll check out my book I Hope I Was Wrong About Eternal Damnation.

February 17, 2022

The Lower Hudson: A paddling gem hidden in plain sight

Stealing adventure inspiration

Stealing adventure inspiration A few year ago, Angel and I were at a bookstore in Seattle, and I stumbled on a book in the local section by David Ellingson, called ,Paddle Pilgrim: Kayaking the Erie Canal and Hudson River to the Statue of Liberty. I neither bought nor read the book, but I really should, because it set off a series of events that led to a mini-epic paddle of the lower Hudson.

As thru-hikers, trail runners and international backpackers, Angel and I are generally happiest on extended adventures of the type where you can settle into the rhythm of living outside, and can start to forget, at least for a while, that life is anything but exploration. I happened on the book at a time when we had just bought foldable ,Oru Kayaks and were learning to use them, and when we'd just finished a year and a half of thru-hiking and backpacking in Latin America and were looking for something new. When I flipped through the book I thought, "Hmm. kayak touring? I wonder if we could pull this off in these Orus?" When an opportunity arose to visit the East Coast a couple of months later, we found ourselves putting in at Albany to recreate the part of the "Paddle Pilgrim" experience, spending a week and a half trying to make our way to NYC by way of the Hudson.

We'd planned to tackle about 150 miles of the Lower Hudson, which is all a part of the ,Hudson River Greenway Water Trail - a national water trail - which means that there are camping or hotel accommodations and launches at least every 15 miles on both sides of the river, and in most cases more frequently than that. Campsites and boat racks could have been more abundant and accessible, but otherwise the logistics of planning this trip were straightforward. There were plenty of places to get water, to resupply food, or to pop off the river for a shower and a night in a hotel. Things are set up there for long distance paddling, and we found that it was a challenge that we as fit people, but relatively inexperienced paddlers, could take on confidently and safely.

Beyond "Paddle Pilgrim", there are a few online articles about people who've taken this trip, but we didn't meet any one else doing even sections while we were out, and several locals told us they'd never heard of anyone doing the whole trip. Even being early in the season, that was surprising due to the ease of access and logistics, the availability of comprehensive maps and ,even a guidebook, the proximity to one of the largest concentrations of people in the world, and the fact that the river is perfectly set up for such a trip.

Our approach was to apply the lessons we've learned thru-hiking to an extended kayaking trip: pack as light as possible, embrace our inner dirtbag, chill out, and look out for both type 2 and type 1 fun: work hard while enjoying it as much as we could.

This was our first extended paddling trip, so didn't want to get in over our head, but we did want to see what our Oru Kayaks were capable of. Oru was a relatively new company with an innovative concept - a highly functional but lightweight origami-esque folding kayak that you can toss on your back and take to places that a normal kayak wouldn't easily go: two miles up trail to a mountain lake, for instance, or (in our case) the checked baggage carousel on an airplane and the luggage compartment of a Greyhound bus. We wanted to be as self-contained and human powered as we could, and do it on the cheap without car rentals or paid boat transportation.

Hudson River PeopleWe tend to like our adventures with a side of community, and we found that meeting cool people along this route came naturally. People along the river seemed universally interested in what we were doing, and offered us important advice like which bushes to stash our kayaks in when we were spending the night in town, and where to find the local breweries. On one occasion when we were lugging our packs up a hill, a guy mistook us for Appalachian Trail thru-hikers and offered us a ride to the trailhead at Bear Mountain. (Thru-hikers can't escape trail magic even if they try.) West Coast rumors of East Coast rudeness are greatly exaggerated.

River Towns

River TownsFor its access to history and quaint small towns, the lower Hudson is a sort of poor American paddler's version of the Camino de Santiago in Spain. There are towns, I'd say on average, every 10 miles along the river, and history is everywhere - from the giant manors, light houses, and literal castles dotting the river, to the ruins of ice houses where the frozen Hudson was broken up, stored and shipped down river, to the islands seemingly made entirely of the bricks that were produced to construct New York City.

Most of the towns are quaint maritime villages, but you get a range of experiences from a place like Coxsackie that is almost a ghost town to Beacon, which is a bustling arts community full of NYC refugees. In general the community along the Hudson is vibrant, and a highlight was wandering by accident into a Spring Festival in Highland, across the river from Poughkeepsie, where we gorged on street food and local beer while we waited on our laundry to dry at the local laundromat.

Outdoor adventure on an industrial river

Outdoor adventure on an industrial riverOne of the things I love about paddling is that it allows you to easily get out of the controlled environment of the city into the heart of nature without much travel Despite the fact that the Hudson is a relatively populated river, living on the water for a week and a half felt like a real outdoor experience, where wind, storms, and the tidal nature of the river were the primary challenges we had to contend with on a daily basis.

If you're not from the area, the Hudson itself is probably not exactly what you think: it has a reputation as a highly polluted waterway, and in places around the city it still has issues. But while the river is still impacted by its industrial history, NY has engaged in massive cleanup efforts in recent years, and our experience was characterized more by pretty tidal estuaries, abundant bird life, jumping fish, pleasant state parks, and rural villages than visible pollution. Nowadays, it's safe to swim in most places, even if we weren't brave enough to filter our drinking water from the river. The Hudson didn't feel particularly busy either, despite some reports we'd heard. It is an active shipping channel, but above NYC large ships were relatively uncommon - we probably saw 1 - 2 per day - and beyond a few smaller boats we frequently had the river mostly to ourselves.

It's a common saying that the Hudson behaves more like an ocean than a river, and while I think this is a bit of an exaggeration (conditions, when choppy, were very similar to our home base on Lake Washington in Seattle), a sea kayak would have been the ideal tool for the job. Our 12 foot, folding, lightweight and rudderless boats were functional overall, but you will wish that you had a better model. In our case this was typically in high winds, when tailwinds led to tracking problems and headwinds slowed down our lightweight boats more than they might have heavier ones. Our most nerve-wracking experience was during a river crossing at a wide point in high winds, when the river was whitecapping. We intentionally steered relatively close by some stationary smaller fishing boats so we'd have aid in case we capsized, and they cheered for us while we navigated some pretty gnarly chop. In the end our boats contributed to our decision to cut our trip about 30 miles short at Croton-on-Hudson when high winds were predicted and we didn't want to contend with tough conditions along with the increased large ship traffic near NYC. But generally speaking, the Oru's were what we expected them to be: light, functional, and fun, and pretty darn good for an affordable boat you can pack up, throw on your back, and cart around the city when you're done. And you can't really beat the cool factor.

Here's to hoping the trip becomes famous

Here's to hoping the trip becomes famousIt's strange that a paddle down a river that fronts possibly the most famous city in the world would feel like discovering a hidden gem, but because we didn't come across anyone else doing the same thing, this trip really did. 150 mile paddling trips might not be everyone's thing, but the fact that NYC sits at the end of a really fantastic one suggests to me that there's significant economic and adventure potential for the Hudson that hasn't yet been realized. It's a world-class paddling experience hidden in plain sight. To me, it's a water trip that captures a similar magic to the Camino de Santiago, or the Appalachian Trail, and an outdoor experience that was full of natural beauty, culture, and history.

Check out my book The Dirtbag's Guide to Life for a comprehensive plan for how to make things like paddling the Lower Hudson your lifestyle, and not just a daydream.

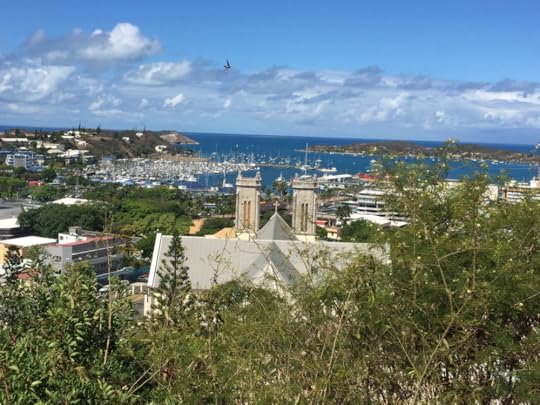

How to discover island paradise on the cheap in New Caledonia.

If you’re the type of person who daydreams about:

Living in a hut on a tropical beach where no one’s around but a couple of French beach bums and some wild boar, and staring out at the blue, blue ocean to contemplate whatever it is you need to contemplate, Finding your own small, empty, island to hole up on, or Dropping off grid to carve out a life that doesn’t require much of anything,it might be worth thinking about New Caledonia.

I’m not sure if you can do those things there, but it seems like you probably could.

If you haven’t heard of it, New Caledonia is a small group of islands and islets in Melanesia - forming a roughly equilateral triangle with Australia and New Zealand, where it is the Northeasterrnmost point. It’s not that far from Vanuatu, if that helps.

If you aren’t already there, it’s almost definitely a long way from where you are. We booked an AirBnB on a woman’s catamaran in the main harbor in the capitol, and she told us that a lot of people arrive by boat and fly home, ditching their vessels because it’s too much trouble to get them back to Europe or the United States or wherever they’ve drifted in from.

It's pretty sleepy, but it still does a healthy tourist trade with English speakers and people from mainland China and Japan. The main group of foreigners, though, are French. The proper official name is Nouvelle Caledonie, because since 1853 the French have put themselves in charge of things. Along with a lot of blue water, the islands have one of the richest nickel deposits in the world, and the white people there taking it are primarily francophones.

Originally though, it was a Melanesian paradise - Kanak, specifically. People have been there for 3000 years, which is pretty incredible when you think about it. The Kanak people still make up 40 percent of the population, and their culture is alive and quite visible all over the islands. As is the case everywhere I’ve been in the Pacific, they seem to exist in a uneasy detente with their colonizers. Just before we arrived in November 2018, there was a national referendum on whether or not to remain a French colony. Kanak flags were flying everywhere, and only 56% voted to stay.

We didn't know any of that before we arrived, and our own trip to the country happened mostly on a whim. We were looking for flights between the South and North Island of New Zealand, and noticed a cheap flight to a place called “Noumea”. We Googled it, found out it was the capital of a country we’d never thought much about, and decided “what the hey?!”

We were only there for a week, and I’m by no means an expert, or even a novice, but we did dig around enough to function something like scouts for others out there who might be interested in paying a visit.

What's New Caledonia like?